Abstract

Objective

Cholecystolithiasis is a common disease in the elderly patient. The routine therapy is open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In the previous study, we designed a minimally invasive cholecystolithotomy based on percutaneous cholecystostomy combined with a choledochoscope (PCCLC) under local anesthesia.

Methods

To investigate the effect of PCCLC on the gallbladder contractility function, PCCLC and laparoscope combined with a choledochoscope were compared in this study.

Results

The preoperational age and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores, as well as postoperational lithotrity rate and common biliary duct stone rate in the PCCLC group, were significantly higher than the choledochoscope group. However, the pre- and postoperational gallbladder ejection fraction was not significantly different. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses indicated that the preoperational thickness of gallbladder wall (odds ratio [OR]: 0.540; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.317–0.920; P=0.023) and lithotrity (OR: 0.150; 95% CI: 0.023–0.965; P=0.046) were risk factors for postoperational gallbladder ejection fraction. The area under receiver operating characteristics curve was 0.714 (P=0.016; 95% CI: 0.553–0.854).

Conclusion

PCCLC strategy should be carried out cautiously. First, restricted by the diameter of the drainage tube, the PCCLC should be used only for small gallstones in high-risk surgical patients. Second, the usage of lithotrity should be strictly limited to avoid undermining the gallbladder contractility and increasing the risk of secondary common bile duct stones.

Introduction

The prevalence of cholecystolithiasis in adults is ~10%, especially higher in the aged. The history of surgical treatment of cholecystolithiasis has been more than 100 years. In 1987, the first case of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) was carried out. As the invasive surgery technique progressing, LC expands the subject range of invasive surgical management of gallstone. However, with the recognition of the importance of gallbladder function, more and more patients are aware of the consequence of LC, such as biliary injury and dyspepsia problem. Some novel strategies to remove the stone and preserve gallbladder are adopted. Tan et al introduces a novel strategy using laparoscope combined with choledochoscope (LSC) to extract the gallstones.Citation1 Kim et al report an original fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous gallstones removal.Citation2 Some other methods include oral dissolution therapy and extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL).Citation3,Citation4

In a previous study, we put forward an idea of invasive percutaneous cholecystolithotomy (PCCL) methods based on percutaneous cholecystostomy combined with choledochoscope (PCCLC) under local anesthesia.Citation5 No matter which methods are adopted, the recurrence rate must first be taken into consideration. Wang et alCitation6,Citation7 propose the idea that the formation of gallstones is a systemic and genetic procedure with dysmetabolism of cholesterol and biliary bile acids as well as dysfunctional gallbladder motility accompanied with the hypersecretion of mucins. Meanwhile, the recurrence rate of gallstones in patients with poor gallbladder function before PCCL was significantly higher than in those without this factor.Citation8–Citation10 To investigate the long-term recurrence rate post operation, the change in gallbladder function needs to be demonstrated first.

In this study, the gallbladder contractility functions between two different invasive strategies were compared.

Patients and methods

General information

From January 2010 to December 2014, consecutive 48 patients, who were diagnosed as cholecystolithiasis by ultrasound after admission, were treated with cholecystolithotomy. The patients were grouped into the PCCLC group and the LSC group according to the disparity of surgical methods. All patients were willing to undergo the minimally invasive surgery. The surgical plans were discussed and approved by the Chengdu Military Hospital Ethics Committee. The Declaration of Helsinki for Medical Research has been strictly adhered to. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients to participate in this study and for the publication of the associated images.

Materials and equipment

PCCL in the PCCLC group was performed using Philips iu22 ultrasound system (Philips, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Pigtail Drainage Catheter Set (7-Fr and 16-Fr; Bioteque, Taipei, People’s Republic of China), and Amplatz Dilator Set (12–22-Fr; Cook, Bloomington, IN, USA). Retrieval or pulverization of the gallstone was performed using Trapezoid RX Wire-guided Retrieval Basket (Boston Scientific, Boston, MA, USA) and Pentax EPM-3500/ECN-1530 (Pentax, Tokyo, Japan) choledochoscope system under local anesthesia. The LSC group adopted Olympus HD EndoEYE (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and Trapezoid RX Wire-guided Retrieval Basket (Boston Scientific) to execute the surgery under general anesthesia.

Methods

The procedures of PCCLC

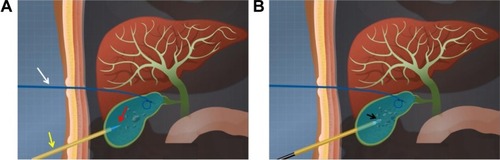

The PCCLC procedures were performed as described before.Citation5 In brief, a primary 7-Fr pigtail drainage catheter was percutaneously and trans-hepatically inserted into the neck of the gallbladder under ultrasound guidance using a single trocar technique. The secondary 16-Fr catheter was percutaneously non-transhepatically inserted at the bottom of the gallbladder using the same method (). The secondary catheter was used as the choledochoscope working tract. After the secondary catheter was dilated into 22-Fr, a 20-Fr sheath was carried into the gallbladder cavity. The choledochoscope was inserted into the gallbladder along with the 20-Fr sheath to grasp stones using the stone extractor or pulverize the stones ().

Figure 1 The schematic representation of percutaneous cholecystostomy combined with choledochoscope procedures.

The procedures of LSC

The LSC procedures were performed under general anesthesia. The locations of the puncture points and the surgical methods were similar with regular LC. Then a small incision was made at the bottom of the gallbladder according to the size of the stone. After the bile was suctioned, the choledochoscope was introduced into the gallbladder. The rest procedures of pulverization or retrieval of the gallstone were similar with PCCLC. At last, the incision of the gallbladder and the abdomen was closed using a running suture. To avoid bile leakage, a 7-Fr drainage tube was routinely placed.

Follow-up

After the surgery, antibiotics and an anti-hemorrhagics were given to the patients in the traditional manner. While this procedure was minimally invasive, the patients could be monitored in a regular ward or in the intensive care unit if necessary. The secondary catheter of PCCLC was removed after the ultrasound confirmed that there were no residual stones. The primary catheter in the PCCLC group and the drainage tube in the LSC group were reserved for drainage after the patient was discharged, and it was extracted in a clinic service setting after the sinus returned to normal. To avoid relapse, the patients were prescribed taurocholate ursodeoxycholic acid when they were discharged. After all the drainage tubes were removed, the gallbladder contractility function was detected.

Gallbladder contractility function

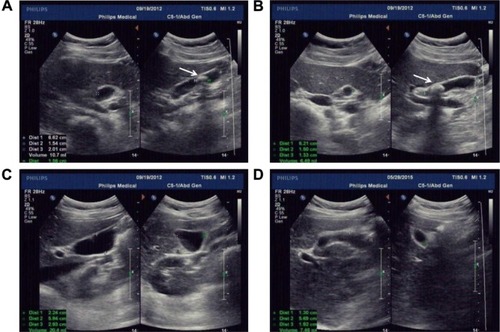

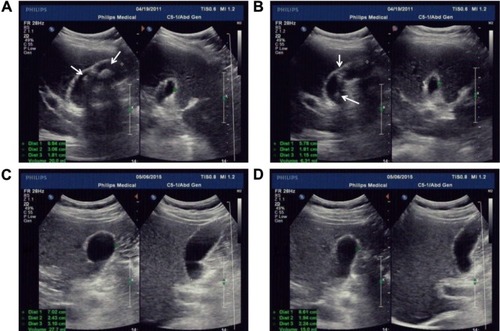

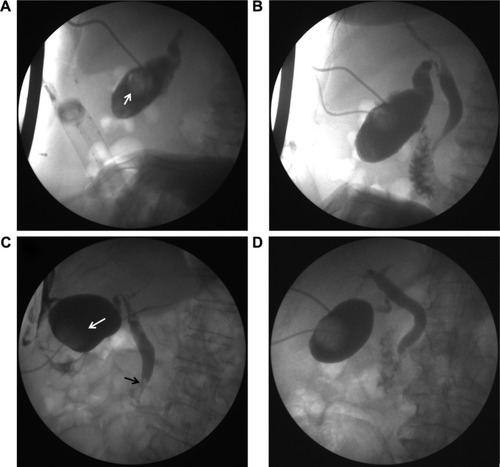

Gallbladder contractility function was represented by fasting gallbladder volume (FGBV), postprandial gallbladder volume (PGBV), and gallbladder ejection fraction (GBEF), which were calculated by ultrasonography. Gallbladder volume (GBV) was determined by the formula: GBV =π/6× (L × W × H), with dimension sagittal length (L), width (W), and axial height (H). GBEF was determined using the following formula: GBEF (%) = (FGBV − PGBV)/(FGBV) ×100%. PGBV was the volume at 30 minutes after a high-fat diet ( and ). Ultrasonographic studies were performed by the same investigator.

Figure 2 A significant alleviation of GBEF before and after surgery.

Notes: (A, B) Preoperational ultrasound results. Preoperational ultrasound found a single stone with a diameter of 15.6 mm. The white arrow shows the single stone. Preoperational GBEF was 39%. (C, D) Postoperational ultrasound results. Postoperational ultrasound found no stone residual. Postoperational GBEF was 63%.

Abbreviation: GBEF, gallbladder ejection fraction.

Figure 3 A significant deterioration of GBEF before and after surgery.

Abbreviation: GBEF, gallbladder ejection fraction.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and evaluated using Fisher’s exact t-test or Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical data were described with frequency counts and assessed using the χ2 test. Two-tailed P-values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patients

A total of 48 cholecystolithiasis cases were included: the PCCLC group included 17 (31.42%) cases and the LSC group included 31 (64.58%) cases. The characteristics of the patients are shown in . The average age of patients in the PCCLC group was 41.2±13.7 versus 33.9±7.7 years in the LSC group. The preoperational GBEF was not significantly different between the two groups. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores in both groups were 3.1±0.6 and 2.7±0.4, respectively. The higher age (P=0.018; ) and ASA scores (P=0.008; ) in the PCCLC group than that in the LSC group indicated that patients in the PCCLC group might face higher surgical risks.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of all patients in each group

Characteristics of complications and outcomes of patients

delineated the therapeutic outcomes of the three groups. Due to the oversize of gallstones, a total number of 10 patients received the lithotrity treatment during the operation. A significantly higher lithotrity rate in the PCCLC group (7 cases, 41.12%) than that in the LSC group (3 cases, 9.68%; P=0.022; ) was observed, as well as higher incidence of choledocholithiasis (23.53% versus 3.23%; P=0.047; ). With lots of fragment stones being generated, it may result in the secondary common bile duct (CBD) stones. Nevertheless, the admission day was shorter in the PCCLC group (4.5±0.8 versus 4.9±0.4; P=0.018; ). No significant differences were found between the two groups in postoperational GBEF, the postoperational thickness of gallbladder wall, duration of the drainage tube, quality of life (QOL) and complications, such as bleeding and bile leakage.

Table 2 Characteristics of complications and outcomes of patients

Interestingly, we found that the number of patients whose GBEF was >50% had increased after surgery in both groups. However, compared with GBEF before surgery, there was no significant difference (P=0.732 in the PCLC group and P=0.611 in the LSC group; ).

Table 3 Pre- and postoperational GBEF in each group

To analyze which clinical factors played a crucial role in postoperational GBEF alleviation, patients were grouped according to whether their postoperational GBEF is more than 50%. Then, univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted in the next section.

Logistic regression analysis

showed the factors indicative of GBEF alleviation after surgery. These variables were significantly different between GBEF alleviation and non-alleviation after surgery: thickness of gallbladder wall (odds ratio [OR]: 0.541; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.336–0.872; P=0.012; ) and lithotrity (OR: 0.146; 95% CI: 0.027–0.785; P=0.025; ). These factors were described as potential predictors for GBEF alleviation after surgery and were analyzed as variables in the multivariable logistic regression model.

Table 4 Univariable logistic regression analysis of postoperational GBEF

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, thickness of gallbladder wall (OR: 0.540; 95% CI: 0.317–0.920; P=0.023; ) and lithotrity (OR: 0.150; 95% CI: 0.023–0.965; P=0.046; ) were found to be significantly different between GBEF alleviation and non-alleviation after surgery and were, therefore, identified as risk factors.

Table 5 Multivariable logistic regression analysis of postoperational GBEF

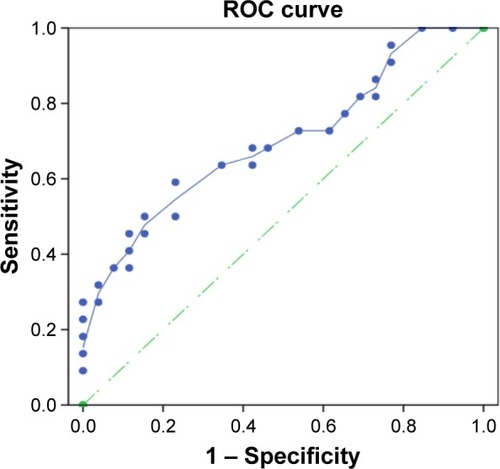

For further assessment of the thickness of the gallbladder wall to the GBEF, the area under the curve (AUC) was adopted. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) was 0.714 (P=0.016; 95% CI: 0.553–0.854; ). It seemed that patients with a thicker gallbladder wall might deserve a worse GBEF alleviation after surgery. In many cases, the thickness of the gallbladder wall was correlated with the inflammatory severity of the gallbladder.Citation11,Citation12

Figure 4 ROC analysis of the gallbladder wall in predicting the postoperational gallbladder contractility.

Abbreviation: ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve.

Discussion

In recent years, gallstones have turned into one of the most common diseases, especially in older patients. With minimally invasive surgery equipment and surgical technique being ameliorated, LC has taken over from open cholecystectomy (OC) and has been placed at the top of the patients’ priority list. However, neither OC nor LC is able to apply to those older patients with high surgical risk, who might not be able to tolerate the anesthesia either. Age and ASA scores may be the two insurmountable barriers. In an attempt to conquer these two barriers, we have introduced a novel method based on ultrasound-guided double-tract per-cutaneous cholecystostomy and choledochoscope cholecystolithotomy (also called PCCLC), which is conducted totally under local anesthesia.Citation5 Compared with traditional LSC in this study, it is demonstrated that PCCLC can be safely applied to older people with high ASA scores. Meanwhile, the admission day after PCCLC is shortened significantly. Although PCCLC may result in additional lithotrity and a higher incidence of secondary CBD stone and endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST; ), other PCCLC-related complications such as bleeding and bile leakage, postoperational GBEF, duration of the drainage tube, and QOL are similar to LSC.

Figure 5 Postoperational cholecystography results.

The application of lithotrity and lithotomy are still controversial due to the possibility of gallstone relapse. It is reported that the recurrence rate of gallstones in patients with poor gallbladder function before PCCL was significantly higher than in those without this factor.Citation8–Citation10 Although we find that both postoperational GBEFs are slightly elevated (from 21/48 to 26/48) compared with preoperational GBEF, there is no statistical difference between the two groups.

To investigate which factors have played the crucial role in the alleviation of GBEF, the results of this study indicate that preoperational thickness of the gallbladder wall is the independent risk factor for the poor GBEF. The thickness of the gallbladder wall plays an increasingly important role in gallbladder diseases diagnosis.Citation13 Not only can the thickness of the gallbladder wall be correlated with acute cholecystitis but it also is able to present chronic cholecystitis. Referring to acute cholecystitis, Zenobii et alCitation14 indicate that gallbladder wall thickening can represent the acute inflammatory conditions. In addition, gallbladder wall edema is found to be a predictive factor of severe acute cholecystitis.Citation15 When it comes to chronic cholecystitis, patients with symptomatic chronic calculous cholecystitis not only have gallstones but also histopathological evidence of chronic inflammation of the gallbladder wall, who may also suffer from a functional abnormality, such as poor contractility.Citation16,Citation17 In our research, those elderly patients are suffering from chronic cholecystitis accompanied with a long course of the disease, which can dramatically affect the gallbladder contractility. We also find that the preoperational thickness of the gallbladder wall is the independent risk factor for the poor postoperational GBEF. The thickness of gallbladder wall >3 mm is proved to be coincidence with the inflammatory severity of gallbladder.Citation18 In addition, in a novel preoperative clinical scoring system for acute cholecystitis, a gallbladder wall thickness of >4 mm is correlated significantly with high scores.Citation19 In this study, we find that the preoperational thickness of gallbladder wall of 3.5 mm is the cutoff point for the poorer and better postoperational GBEF. In liver cirrhosis patients, Loreno et alCitation20 demonstrate that structural changes of the gallbladder wall could induce wall thickening and also affect gallbladder contractility. On the basis of all the findings of other research groups and our group, no matter which surgical method is adopted, LC, or PCCLC, or LSC, the preoperational gallbladder wall thickness should be taken into account seriously.

As to lithotrity, an enormous emphasis has been shifted toward gallstone patients who are treated by ESWL. However, Cesmeli et alCitation21 report that there is a significant association of stone recurrence with a number of lithotrity sessions and estrogen intake in ESWL patients. However, the underlying reasons need to be further illustrated. Both Tsumita et alCitation22 and Venneman et alCitation23 give a clue that the probability of stone recurrence is significantly higher in patients with poor gallbladder contractility than in those with good contractility. Ochi et alCitation24 provide a link that the rate of impaired gallbladder contractility was higher in ESWL patients with recurrence when compared with those with no recurrence. Our research gives another link that lithotrity may result in impaired gallbladder contractility, which functions as a bridge between lithotrity and stone recurrence. With lots of fragment stones being generated, it may result in the secondary CBD stones. Hence, lithotrity must be used on the condition that there are no other alternatives.

Although our PCCLC strategy is performed under local anesthesia, it should be carried out cautiously. First of all, being restricted by the diameter of the drainage tube, the PCCLC strategy should be used only for the management of small gallstones in high-risk surgical patients, who are not able to tolerate anesthesia. It also can reduce the chance of lithotrity. Second, the usage of lithotrity should be strictly limited to avoid undermining the gallbladder contractility. With lots of fragmental stones being generated, lithotrity may put the patient at a high risk of unexpected secondary CBD stones.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Qi Chen and Hui Zhang who are excellent physicians, and the authors thank them for their ultrasound guidance. The authors also thank practiced choledochoscope physicians Dr Bing-yin Zhang, Dan-qing Liu, and Shang-qin Huang for their valuable contribution. They also thank Jiongran Medical Art Studio for the schematic of PCCLC procedures.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- TanYYZhaoGWangDWangJMTangJRJiZLA new strategy of minimally invasive surgery for cholecystolithiasis: calculi removal and gallbladder preservationDig Surg2013304–646647124481280

- KimYHKimYJShinTBFluoroscopy-guided percutaneous gallstone removal using a 12-Fr sheath in high-risk surgical patients with acute cholecystitisKorean J Radiol201112221021521430938

- RabensteinTRadespiel-TrogerMHopfnerLTen years experience with piezoelectric extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy of gallbladder stonesEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200517662963915879725

- TazumaSNishiokaTOchiHImpaired gallbladder mucosal function in aged gallstone patients suppresses gallstone recurrence after successful extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsyJ Gastroenterol Hepatol200318215716112542599

- WangTChenTZouSUltrasound-guided double-tract percutaneous cholecystostomy combined with a choledochoscope for performing cholecystolithotomies in high-risk surgical patientsSurg Endosc20142872236224224570012

- WangHHPortincasaPde BariOPrevention of cholesterol gallstones by inhibiting hepatic biosynthesis and intestinal absorption of cholesterolEur J Clin Invest201343441342623419155

- WangHHPortincasaPAfdhalNHWangDQLith genes and genetic analysis of cholesterol gallstone formationGastroenterol Clin North Am201039218520720478482

- ZouYPDuJDLiWMGallstone recurrence after successful percutaneous cholecystolithotomy: a 10-year follow-up of 439 casesHepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int20076219920317374582

- PazziPPetroniMLPrandiniNPostprandial refilling and turnover: specific gallbladder motor function defects in patients with gallstone recurrenceEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200012778779410929907

- PetroniMLJazrawiRPPazziPRisk factors for the development of gallstone recurrence following medical dissolution. The British-Italian Gallstone Study GroupEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200012669570010912491

- CwikGSkoczylasTWyroslak-NajsJWallnerGThe value of percutaneous ultrasound in predicting conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy due to acute cholecystitisSurg Endosc20132772561256823371022

- SantosBFAuyangEDHungnessESPreoperative ultrasound measurements predict the feasibility of gallbladder extraction during transgastric natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery cholecystectomySurg Endosc20112541168117520835721

- XuJMGuoLHXuHXDifferential diagnosis of gallbladder wall thickening: the usefulness of contrast-enhanced ultrasoundUltrasound Med Biol201440122794280425438861

- ZenobiiMFAccogliEDomanicoAArientiVUpdate on bedside ultrasound (US) diagnosis of acute cholecystitis (AC)Intern Emerg Med201611226126426537391

- BorzellinoGSteccanellaFMantovaniWGennaMPredictive factors for the diagnosis of severe acute cholecystitis in an emergency settingSurg Endosc20132793388339523549766

- RaymondFLepantoLRosenthallLFriedGMTc-99m-IDA gallbladder kinetics and response to CCK in chronic cholecystitisEur J Nucl Med1988147–83783813181187

- ZiessmanHAFunctional hepatobiliary disease: chronic acalculous gallbladder and chronic acalculous biliary diseaseSemin Nucl Med200636211913216517234

- VillarJSummersSMMenchineMDFoxJCWangRThe absence of gallstones on point-of-care ultrasound rules out acute cholecystitisJ Emerg Med201549447548026162764

- AmbePCPapadakisMZirngiblHA proposal for a preoperative clinical scoring system for acute cholecystitisJ Surg Res2016200247347926443188

- LorenoMTravaliSBucceriAMScalisiGVirgilioCBrognaAUltrasonographic study of gallbladder wall thickness and emptying in cirrhotic patients without gallstonesGastroenterol Res Pract2009200968304019680454

- CesmeliEElewautAEKerreTDe BuyzereMAfschriftMElewautAGallstone recurrence after successful shock wave therapy: the magnitude of the problem and the predictive factorsAm J Gastroenterol199994247447910022649

- TsumitaRSugiuraNAbeAEbaraMSaishoHTsuchiyaYLong-term evaluation of extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy for cholesterol gallstonesJ Gastroenterol Hepatol2001161939911206322

- VennemanNGvanBerge-HenegouwenGPPortincasaPAbsence of apolipoprotein E4 genotype, good gallbladder motility and presence of solitary stones delay rather than prevent gallstone recurrence after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsyJ Hepatol2001351101611495026

- OchiHTazumaSKajiharaTFactors affecting gallstone recurrence after successful extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsyJ Clin Gastroenterol200031323023211034003