Abstract

Background

Frailty is an aging syndrome caused by exceeding a threshold of decline across multiple organ systems leading to a decreased resistance to stressors. Treatment for frailty focuses on multi-domain interventions to target multiple affected functions in order to decrease the adverse outcomes of frailty. No systematic reviews on the effectiveness of multi-domain interventions exist in a well-defined frail population.

Objectives

This systematic review aimed to determine the effect of multi-domain compared to mono-domain interventions on frailty status and score, cognition, muscle mass, strength and power, functional and social outcomes in (pre)frail elderly (≥65 years). It included interventions targeting two or more domains (physical exercise, nutritional, pharmacological, psychological, or social interventions) in participants defined as (pre)frail by an operationalized frailty definition.

Methods

The databases PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, PEDro, CENTRAL, and the Cochrane Central register of Controlled Trials were searched from inception until September 14, 2016. Additional articles were searched by citation search, author search, and reference lists of relevant articles. The protocol for this review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42016032905).

Results

Twelve studies were included, reporting a large diversity of interventions in terms of content, duration, and follow-up period. Overall, multi-domain interventions tended to be more effective than mono-domain interventions on frailty status or score, muscle mass and strength, and physical functioning. Results were inconclusive for cognitive, functional, and social outcomes. Physical exercise seems to play an essential role in the multi-domain intervention, whereby additional interventions can lead to further improvement (eg, nutritional intervention).

Conclusion

Evidence of beneficial effects of multi-domain compared to mono-domain interventions is limited but increasing. Additional studies are needed, focusing on a well-defined frail population and with specific attention to the design and the individual contribution of mono-domain interventions. This will contribute to the development of more effective interventions for frail elderly.

Introduction

Frailty is a late-life syndrome that results from reaching a threshold of decline across multiple organ systems.Citation1 Because frailty leads to excess vulnerability and reduced ability to maintain homeostasis, frail elderly are predisposed to functional deficits, comorbidity, and mortality.Citation1,Citation2

Despite a lack of international consensus on the definition of frailty, two conceptual definitions are commonly used.Citation3,Citation4 First, Fried et al introduced the frailty phenotype and described frailty based on the presence of five physical characteristics: unintentional weight loss, weakness, exhaustion, slow gait, and low physical activity.Citation5,Citation6 Subjects are considered robust (no criteria present), prefrail (1 or 2 criteria present), or frail (3–5 criteria present).Citation5 Second, the frailty index of Rockwood and Mitnitski defines frailty as an accumulation of heterogeneous deficits identified by a comprehensive geriatric assessment.Citation7 The index reflects the proportion of present deficits to the total number of potential deficits, to determine whether a patient is robust (≤20%), prefrail (20%–35%), or frail (≥35%).Citation7,Citation8 The frailty index represents a broader scope of frailty, including cognitive, social, and psychological components, next to the physical characteristics. Although the frailty syndrome includes multiple domains, physical frailty (and more specifically musculoskeletal frailty) is seen as the main component of frailty.Citation2,Citation9

Depending on the frailty definition and evaluation tool, frailty prevalence ranges between 4.0% and 59.1% in community-dwelling people aged >65 years.Citation10 As the population ages, frailty represents increasingly important public health concerns and has an incremental effect on health expenditures (additional ±€1500/frail person/year).Citation11,Citation12 Because of the major clinical and economic burden, it is critical to find efficient, feasible, and cost-effective interventions to prevent or slow down frailty in order to avoid or diminish the adverse outcomes and maintain or improve quality of life.Citation1,Citation9

Frailty is possibly reversible or modifiable by interventions.Citation13–Citation16 Previous research on nonpharmacological interventions such as physical exercise and nutritional interventions showed promising effects on frailty status, functional outcomes, and cognitive outcomes.Citation17–Citation19 These interventions can be combined with each other or with other (eg, pharmacological, hormonal, or cognitive) therapies to prevent or treat frailty.Citation20 As frailty results from reaching a threshold of decline in different physiological systems, the approach to address frailty should act on multiple domains.Citation13,Citation21

Previous overviews of multi-domain interventions only examined combinations of exercise and nutritional interventions.Citation22 Also, studies combining more than two domains were not in their scope of interest.Citation23 Other reviews focused on other populations (eg, sarcopenia or obesity)Citation22,Citation24–Citation26 or included studies that used no diagnostic tool to determine the frail populationCitation27,Citation28 or used poor search criteria for (pre) frail participants (eg, only one keyword in database search).Citation29 Because of the limitations of existing reviews as well as to include information from recent studies, a systematic review was conducted, aiming to provide an overview of the effects of controlled multi-domain interventions in (pre)frail people aged ≥65 years on frailty status and score, cognition, muscle mass strength and power, and functional and social outcomes.

Methodology

The review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42016032905) and was reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.Citation30

Search methods

First, a systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, PEDro, CENTRAL, and the Cochrane Central register of Controlled Trials from inception of the database until September 14, 2016, to ensure comprehensive article retrieval. The search strategy was developed for PubMed (Figure S1) and then translated for use in other databases (available upon request). The literature search was limited to articles published in English, Dutch, French, or German and excluded case reports, letters, and editorials. Second, additional studies were searched by hand-searching reference lists, citations, and other publications from first and last authors from relevant papers retrieved in the first search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria are as follows: 1) randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, or prospective or retrospective cohort studies with control groups; 2) testing of a multi-domain intervention to prevent or treat frailty in people aged ≥65 years; 3) classification in terms of (pre) frailty status according to an operationalized definition; and 4) primary outcomes including one or more of the following: frailty status or score, muscle mass, strength or power, physical functioning, and cognitive or social outcomes.

A multi-domain intervention was defined as an intervention that intervenes in at least two different domains, including exercise therapy (Ex), nutritional intervention (supplementation of proteins [NuP], supplementation of vitamins and minerals [NuVM], milk fat globule membrane [NuMF], or nutritional advice [NuAd]), hormone (Hor), cognitive (Cog) or psychosocial (PS) interventions. Studies that did not compare groups in view of the delivered multi-domain intervention were excluded.

Study selection

Identification of potentially relevant papers based on title and abstract was conducted by one reviewer (LD). Thereafter, the full texts of all potentially relevant abstracts were examined for eligibility. In case of inconclusiveness, a second reviewer (JT) was consulted to discuss eligibility. In case of disagreement, consensus was sought between the reviewers or involvement of a third reviewer (EG) was asked.

Critical appraisal

Risk of bias in the individual studies was assessed by the methodological index for nonrandomized studies (MINORS). The following 12 MINORS criteria were evaluated by two independent researchers (LD and MD): clearly stated aim, inclusion of consecutive patients, prospective collection of data, endpoints appropriate to the aim of the study, unbiased assessment of the study endpoint, follow-up period appropriate to the aim of the study, loss to follow-up <5%, prospective calculation of the study size, adequate control group, contemporary groups, baseline equivalence of groups, and adequate statistical analyses.Citation31 Each criterion was scored 0 (not reported), 1 (reported but inadequate), or 2 points (reported and adequate), resulting in a total quality score ranging from 0 (low quality) to 24 (high quality).

Data extraction and synthesis

The following data were extracted from the included studies: study characteristics (aim, country, design, and setting), participant characteristics (age and gender), frailty diagnostic tool, characteristics of multi-domain interventions (duration, content, frequency, intensity, follow-up moments, and compliance), characteristics of intervention and control groups (number of participants and loss to follow-up), frailty status or score, cognition, muscle mass, strength or power, functional and social outcomes, and quality-of-life measurements. Data on effect measures (mean ± standard deviation or median [10th–90th percentile]) of the included studies were extracted up to 1 year after the intervention. Data were extracted by one researcher (LD) and checked by a second reviewer (EG or JT). Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers.

The primary outcomes were frailty status, cognition, muscle mass, muscle strength, and power and functional outcomes. Secondary outcomes are quality of life, social involvement, psychosocial well-being, and depression and subjective health. The effects between intervention groups were reported, as this study focuses on the effect of multi-domain interventions compared to mono-domain interventions. No effects over time within individual groups were reported. No meta-analysis was performed due to high heterogeneity of the study interventions and outcomes.

Results

Study selection

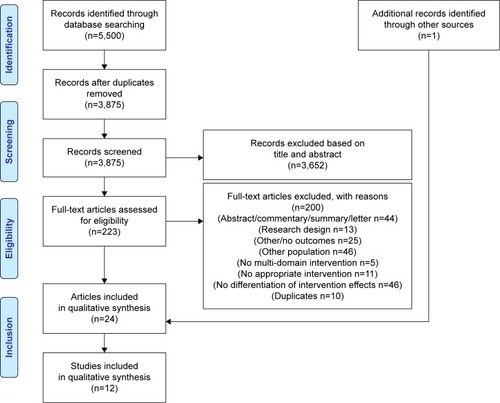

visualizes the study selection process based on the PRISMA flowchart.Citation30 The literature search yielded 5,500 publications. To assess the eligibility of the articles, full texts were read, and 200 articles were excluded with reasons (Table S1). Overall, 24 articles reporting on twelve individual studies met the study eligibility criteria and were included in this systematic review.Citation32–Citation55

Study characteristics

summarizes the study characteristics. Five studies were conducted in Europe,Citation33,Citation46,Citation50,Citation53,Citation54 two in the USA,Citation41,Citation42 and five in Asia.Citation32,Citation43–Citation45,Citation55 Eleven studiesCitation32,Citation33,Citation41–Citation46,Citation50,Citation53,Citation54 had a randomized controlled design and one studyCitation55 had a randomized crossover design. The studies ranged in sample size from 31 to 246.Citation41,Citation45 The duration of the intervention varied between 12 weeksCitation32,Citation43,Citation44,Citation53,Citation55 and 9 months.Citation46 Five studies included a follow-up moment at 3–9 months after the intervention.Citation32,Citation43–Citation46 Nine of the twelve studies were dated from 2010 onwards.Citation32,Citation42–Citation45,Citation50,Citation53–Citation55

Table 1 Study characteristics

One study did not report participant setting,Citation55 whereas all others recruited participants living in the community. Three studies included only women.Citation42–Citation44 To select (pre)frail participants, the Fried frailty phenotype criteria were most frequently used (n=8), often modified or in combination with additional criteria.Citation32,Citation42–Citation45,Citation50,Citation54,Citation55 Two studies used the frailty definition of Chin A Paw et al,Citation33,Citation46 one studyCitation41 used the physical performance test score of Reuben and Siu,Citation90 and one study examined (pre)frailty by the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe Frailty Instrument for Primary Care (SHARE-FI).Citation53 Studies included only frail,Citation33,Citation42,Citation43,Citation46,Citation54 moderate frail,Citation41 only prefrail,Citation44 or both prefrail and frail phenotypes.Citation32,Citation45,Citation50,Citation53,Citation55

Quality of the study

The total methodological quality scores of the included studies ranged from 16 “moderate”Citation33,Citation41 to 23 “excellent”Citation43 (). Only six studies prospectively calculated the sample size.Citation43,Citation45,Citation50,Citation53–Citation55 Baseline differences between intervention and control groups were observed in four studiesCitation32,Citation46,Citation53,Citation54 and were not reported in one study.Citation41

Table 2 Methodological quality assessment of the included studies

Characteristics of the multi-domain intervention programs

summarizes the interventions of the twelve included studies. Nine studies combined two domains in their interventions. Thereof, eight combined a nutritional and physical activity intervention,Citation33,Citation43,Citation44,Citation46,Citation50,Citation53–Citation55 and one combined hormone therapy with physical activity intervention.Citation41 The remaining three studies combined three interventions, of which one study combined exercise, nutritional, and hormone intervention,Citation42 one study combined exercise and nutritional intervention with psychotherapy,Citation32 and one study combined exercise, nutritional, and cognitive interventions.Citation45 All the studies (n=12) included an exercise intervention, and all but one studyCitation42 included a strength training component. Three of the twelve studies included an exercise intervention with only a strength training component,Citation41,Citation50,Citation53 whereas the other nine studies included a multicomponent exercise intervention (at least two of following components: endurance and/or strength and/or balance and/or flexibility). All but one studyCitation41 included a nutritional intervention: four studies provided nutritional advice,Citation32,Citation44,Citation46,Citation53 seven studies provided nutritional supplementation,Citation33,Citation42,Citation43,Citation45,Citation50,Citation54,Citation55 and one study provided both nutritional advice and supplementation.Citation54 Compliance was reported in nine studies:Citation32,Citation33,Citation42,Citation45,Citation46,Citation50,Citation53–Citation55 compliance to the exercise intervention ranged from 47.3%Citation54 to ≥95%,Citation55 and compliance to the nutritional intervention ranged from 73%Citation46 to 100%.Citation55

Table 3 Intervention characteristics

Impact of the intervention strategies on frailty

Change in frailty status and frailty score

Five studies assessed the impact of a multi-domain intervention on frailty status (frail, prefrail, or robust) and/or frailty score (0–5 points) ().Citation32,Citation43,Citation45,Citation53,Citation54 Postintervention, four studies found a significantly improved frailty status or score in the multi-domain intervention groups (Ex + NuMFCitation43; Ex + NuP + NuVM + CogCitation45; Ex + NuAd + PS and Ex + NuAdCitation32; Ex + NuAd + NuVMCitation54) compared to mono-domain intervention groups or control group.Citation32,Citation43,Citation45,Citation54 One study found no significant difference on SHARE-FI score between an Ex + NuAd and a social support intervention.Citation53 At 4 months follow-up, in one study, larger significant improvements were maintained in groups with an exercise intervention irrespective of their additional nutritional intervention (Ex + NuMF and Ex + NuP intervention groups compared to NuP for frailty status, and compared to NuP and NuMF for frailty score).Citation43 In another study, participants of the Ex + NuAd (±PS) intervention did not maintain its significant larger improvement of frailty status at 3 months follow-up compared to control or a PS interventions.Citation32 At 6 months follow-up, the multi-domain Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog intervention of Ng et al showed a significantly improved frailty status and score (higher frailty reduction odds ratio compared to control group) compared to the mono-domain interventions.Citation45 Overall, multi-domain interventions showed significantly larger improved frailty status and score in four studies compared to mono-domain or control interventions.Citation32,Citation43,Citation45,Citation54

Table 4 Frailty outcomes

Impact of the intervention strategies on the elements of the frailty phenotype

Fried et alCitation5 described frailty in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS). More specifically, the Phenotypic Classification of Frailty (CHS-PCF)Citation5 includes five components: unintentional weight loss, weakness, exhaustion, slow gait, and low physical activity.Citation5,Citation6 In the following section, effects of multi-domain interventions in frail elderly on these components are described.

Change in muscle mass (unintentional weight loss)

Seven studies examined muscle mass after a multi-domain intervention (). First, Tieland et al found that adding a protein and mineral supplementation to an exercise intervention significantly improved appendicular and total muscle mass post-intervention.Citation50 Chin A Paw et al found a significantly improved muscle mass by an exercise intervention combined with a protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation intervention compared to protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation.Citation36 Kenny et al found that adding a hormonal dehydroepiandrosterone intervention to an exercise and vitamin and mineral supplementation increased total (but not appendicular) lean mass post-intervention.Citation42 The other four studies found no significant differences between multi-domain and mono-domain interventions. No significant effect was found of adding a milk fat globule membrane (MFGM) or protein supplementation to an exercise intervention.Citation43 Psychosocial intervention (problem-solving therapy) with or without Ex + NuAd intervention compared to no psychosocial intervention or an Ex + NuAd intervention with or without a PS intervention compared to no Ex + NuAd intervention had also no significant effect on muscle mass.Citation32 Also, the combination of Ex + NuAd did not alter muscle mass significantly compared to Ex or NuAd alone or control group.Citation46 Tarazona-Santabalbina et al found that adding exercise to nutritional advice and vitamin and mineral supplementation intervention did not significantly improve muscle mass.Citation54

Table 5 Muscle mass

Change in muscle strength (weakness)

Muscle strength was examined in nine studies, combining Ex + NuP,Citation43,Citation55 Ex + NuMF,Citation43 Ex + NuP + NuVM,Citation33,Citation50 Ex + NuAd,Citation44,Citation46 Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog,Citation45 Ex + NuVM + Hor,Citation42 Ex + HorCitation41 (). One study found that adding protein supplementation to a strength and balance exercise intervention significantly improved leg press strength and knee extension strength but not for hip abduction strength and rowing.Citation55 Two studies examined the effect of 3 months Ex + NuAd.Citation44,Citation46 Rydwik et al found in both Ex + NuAd and Ex groups a significantly improved lower (compared to NuAd) and upper (elbow) (compared to control group) muscle strength post-intervention, but not in shoulder muscle strength.Citation46 Kwon et al found no significant differences between Ex + NuAd and other intervention groups post-intervention.Citation44 At 6 months follow-up, they found significantly declined muscle strength in the Ex + NuAd group compared to the control group.Citation44 The interventions Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog, Ex alone, and Cog alone showed significantly improved lower muscle strength both post-intervention and at 6 months follow-up compared to the control group.Citation45 Finally, Kenny et al found that adding a hormone intervention to an exercise and vitamin and mineral supplementation significantly improved lower but not upper muscle strength.Citation42 Some studies found no significant differences between multi-domain interventions and mono-domain interventions: there was no significant effect in adding an MFGM (NuMF)Citation43 or protein supplementation (with vitamin/mineral supplementation)Citation50 or hormone interventionCitation41 to an exercise intervention. Chin A Paw et al found no significantly improved muscle strength by an exercise intervention combined with a protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation intervention compared to protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation or by combined exercise and nutritional intervention compared to single exercise or no intervention.Citation33

Table 6 Muscle strength

Exhaustion

The exhaustion component of the phenotypical frailty definition cannot be covered in the “Results” section as none of the included articles described the effect of multi-domain interventions on exhaustion.

Gait speed (slow gait)

Seven studies measured gait speed (). Overall, two studies found more improved gait speed in multi-domain interventions including exercise.Citation33,Citation43 Kim et al found that adding an exercise intervention to NuMF supplementation improved gait speed.Citation43 Chin A Paw et al found significant improvements on gait speed by an exercise intervention with protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation intervention compared to protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation.Citation33 Adding nutritional advice or protein supplementation to an exercise intervention showed no significant effect on gait speed, compared to exercise intervention alone.Citation44,Citation46,Citation50 Also, adding a hormone intervention to a vitamin and mineral supplementation and exercise intervention showed no significant effect for gait speed.Citation42 No significant between-group effects were found post-intervention by Ex + Cog + NuVM + NuP intervention compared to single-domain interventions.Citation45

Table 7 Gait speed and physical activity

Physical activity level (low physical activity)

Five studies examined the effect of the intervention on physical activity level (). Adding an exercise intervention to a nutritional advice and vitamin and mineral supplementation increased physical activity.Citation54 Another study found significantly increased physical activity by a NuP + NuVM intervention compared to the control group post-intervention and at 6 months follow-up.Citation45 Physical activity was also increased by Ex intervention alone or Ex combined with NuAd post-intervention and at 6 months follow-up; this increase remained in the Ex group compared to NuAd or control group.Citation47 Kenny et al and Ikeda et al found no significant effect on physical activity of adding a hormone intervention to exercise and nutritional vitamin and mineral supplementationCitation42 and adding a protein supplementation to exercise intervention,Citation55 respectively.

Impact of the intervention strategies on the consequences of frailty

Change in functional abilities

Four studies examined the effect of multi-domain interventions on functional abilities (). Functional abilities are described by activities of daily living (ADL) and/or instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and/or personal activities of daily living dependency or scores. There was a significant improved effect on ADL and IADL by adding an exercise intervention to a nutritional advice and vitamin and mineral supplementation intervention.Citation54 No significant differences were found between a PS intervention (problem-solving therapy) with or without Ex + NuAd intervention compared to no psychosocial intervention or between an Ex + NuAd intervention with or without a PS intervention compared to no Ex + NuAd intervention,Citation32 or between an exercise intervention with protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation intervention compared to protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation or between a combined exercise and nutritional intervention compared to a single exercise or no interventionCitation33 or between Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog compared to Ex or NuP + NuVM or Cog.Citation45

Table 8 Functional abilities and physical functioning

Change in physical functioning

Three studies examined physical functioning by the short physical performance test (SPPB) ().Citation42,Citation50,Citation54 Moreover, Tarazona-Santabalbina et al also assessed the physical performance test and Tinetti balance and gait score.Citation54 The study of Chin A Paw et al assessed performance score and fitness score.Citation33 There was a significant beneficial effect on physical functioning of adding a hormone intervention to a vitamin and mineral supplementation and exercise intervention,Citation42 adding an exercise intervention to a nutritional advice and vitamin and mineral supplementation intervention,Citation54 and of an exercise intervention with protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation intervention compared to protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation on performance score but not fitness score.Citation33 Adding a protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation to an exercise intervention did not show improvements.Citation50

Other frequently described outcomes including cognitive function, muscle power, gait ability, balance, functional lower extremity strength, and falls are described in detail in –.

Table 9 Muscle power

Table 10 Gait ability, balance, functional lower extremity strength, falls

Table 11 Cognitive status

Table S2 summarizes the secondary outcomes quality of life, social involvement, psychosocial well-being/depression, and subjective health.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

Mono-domain nonpharmacological interventions such as physical exercise have shown beneficial effects for frail elderly on gait speed, physical functioning,Citation17 mobility, falls, functional abilities, muscle strength, body composition, and frailty.Citation56 However, no systematic reviews exist on the effectiveness of multi-domain interventions, nor the contribution of a mono-domain intervention to a multi-domain intervention. This systematic review included twelve studies investigating the effect of a multi-domain intervention in frail elderly on frailty status and score, cognition, muscle mass strength and power, and functional, emotional, and social outcomes. These studies were heterogeneous in terms of included participants (frailty diagnostic tool), intervention strategies (type of interventions, number of interventions, and combinations of interventions), and intervention duration. Overall, multi-domain interventions show a greater beneficial impact compared to mono-domain interventions (eg, nutritional intervention alone) or usual care for frailty characteristics, physical functioning, and muscle mass and strength. To be more specific, physical exercise seems to play an essential role in the multi-domain intervention, with some improvements by an additional intervention (eg, nutritional intervention). As suggested in previous reviews, the positive effects of nutritional supplementation increase when associated with physical exercise and the positive effects of physical exercise increase when associated with nutritional supplementation.Citation22,Citation57–Citation59 Also, it could be claimed that the physical exercise component accounts for the greatest improvements, which has also been suggested in reviews discussing frailCitation28 and sarcopenic elderly.Citation22

Multi-domain interventions improve frailty characteristics and physical functioning more effectively than mono-domain interventions

Overall, this review indicates that multi-domain interventions are more effective than mono-domain interventions for several outcomes, such as frailty status or score. More specifically, the combination of physical exercise and nutritional intervention yielded a more positive result on frailty status or score compared to a nutritional interventionCitation43,Citation45,Citation54 or a physical exercise intervention.Citation45 This effect was not found consistently and probably partly depends on variables such as the type and frequency of intervention and target group. The impact of physical exercise on frailty characteristics was previously described.Citation29 It is now of particular interest to mark the added value of the combination of an exercise and nutritional intervention, underlining the contribution of the nutritional intervention to frailty improvements. Moreover, this positive effect on frailty seems to be more prolonged in multi-domain compared to mono-domain interventions. These observations underpin the inherent characteristics of the frailty syndrome: a system-wide syndrome that demands a system-wide approach.

Besides frailty status and score, multi-domain interventions also improved physical functioning (eg, SPPB) more effectively compared to a nutritional intervention,Citation33,Citation54 a combined exercise and nutritional interventionCitation42 or no intervention.Citation33 This is plausible as multiple interventions can act on multiple levels of physical functioning and therefore affect the score of a multifaceted test. Although there is a tendency for improved results by multi-domain interventions, particularly the combination of an exercise and nutritional intervention,Citation33,Citation43,Citation46 the effects were less conclusive for the individual components of the physical functioning test (gait speed, gait ability, balance, and functional lower extremity strength).

Muscle mass and strength showed a tendency to be improved more effectively by multi-domain compared to mono-domain interventions. These results were previously described in reviews in sarcopenic populations.Citation22,Citation57 More specifically, the combined physical exercise and nutritional intervention showed a tendency to improve muscle mass and muscle strength more than exercise or nutritional intervention alone. Skeletal muscle strength does not solely depend on muscle mass but is a function of multiple factors such as nutritional, hormonal, and neurological components and physical activity.Citation60,Citation61 Therefore, it is plausible that the combination of two or more of these interventions will add to the intervention efficacy. In addition, the results seemed to be more consistent when the intervention duration was at least 4 months.Citation33,Citation42,Citation50

The beneficial effects of an exercise intervention alone on frailty,Citation62 muscle outcomes,Citation63 physical functioning,Citation17 quality of life,Citation64 depression,Citation65 and cognitionCitation66 have been described extensively. Although this review did not focus on single-domain interventions, it was observed that the exercise intervention on its own consistently contributed to the core effects on frailty, muscle mass, and muscle strength.Citation33,Citation44–Citation46 Therefore, the role of the exercise intervention seems primordial as part of a multi-domain intervention. Exercise program characteristics (frequency, intensity, duration, and type of training) influence its effects and must therefore be optimized. According to the recent literature, an optimal exercise intervention for frail elderly is performed at least three times a week with progressive moderate intensity for 30–45 minutes per session and for a duration of at least 5 months. The optimal type of exercise intervention is a multicomponent intervention covering aerobic exercise, strength training, balance, and flexibilityCitation67,Citation68 but depends on the outcome that must be improved. The content of the exercise interventions in the different studies in this review is diverse, including several interventions with insufficient training stimulus, for example, training only once a week.Citation44 Exercise interventions with a clear insufficient dose or intensity of training cannot be expected to have an effect, for example, on muscle strength.

The additional effect of combining physical exercise with a nutritional intervention is frequently observed, however not consistently. One argument could be that due to the energy and protein deficits as a consequence of the malnutrition of the participants, the effect of the nutritional intervention is suboptimal because the nutrients are first used to resolve these energy and protein deficits. Malnutrition is often present in community-dwelling elderly;Citation69 moreover, frail elderly have lower intakes of energy, protein, and/or several micronutrients compared to non-frail elderly.Citation70,Citation71 Malnutrition is a result of several factors including anabolic resistance. Anabolic resistance is an aging-associated resistance in response to the positive effects of dietary protein on protein synthesis that elderly develop.Citation72 Several mechanisms underlie anabolic resistance such as splanchnic sequestration of amino acids, decreased postprandial availability of amino acids, and decreased muscle uptake of dietary amino acids.Citation72 Protein intake combined with exercise could increase the anabolic stimulus of exercise. However, due to the anabolic resistance and to obtain beneficial effects of exercise interventions, frail elderly need larger protein intakes. Similarly, physical exercise improves muscle sensitivity to protein or amino acid uptake, consequently counteracting anabolic resistance. Furthermore, the quality and quantity of the nutritional intervention must be emphasized: with insufficient protein intake, an additional effect compared to the exercise intervention alone cannot be expected, similar as when the exercise stimulus is insufficient. Guidelines recommend an intake of 1.2–1.5 g protein/kg bodyweight/day for frail elderly. In addition, each meal should contain 20–40 g protein in order to stimulate muscle protein synthesis in the elderly.Citation73–Citation76 Therefore, nutritional supplementation to reach this threshold must include an assessment of the daily protein intake of the participants. This was done in only one study included in this review.Citation50 As a result, nutritional interventions may be inadequate and results may be misinterpreted. This could lead to an underestimation of the value of nutritional supplementation. To exclude this argument in future, it is important 1) to implement nutritional interventions tailored to the nutritional intake and habits of the participants or 2) to restore the participant’s nutritional status both before the start and during the intervention.

Nutritional status can be targeted directly by adding proteins or nutrients to the diet or indirectly by advising the participant about the importance of several nutrients and how to add them to the diet. Nutritional interventions in this review were heterogeneous in terms of content (NuAd, NuP, NuVM, and NuMF) and design (daily, once a month), resulting in variability in effects. Therefore, no reliable conclusions regarding the stronger intervention can be drawn. To all intents and purposes, direct nutritional supplementation can be advised to achieve direct effects on nutritional status, moreover, higher protein intake was associated with less likelihood of being frail (based on Fried criteria).Citation77 However, teaching the participant to evaluate and adapt his/her own nutritional intake will improve the sustainability of the effect and the compliance to the intervention.

In conclusion, multi-domain interventions, where both exercise and nutritional interventions are optimally designed, reveal a stronger effect as frailty, physical functioning, and muscle mass and strength depend on multiple factors. As a result, we recommend the exercise intervention as an essential part of future multi-domain intervention studies. Moreover, attention must be paid to the design of both exercise and nutritional interventions to elucidate the optimal effect of the interventions. In addition, the compliance of the participants to the interventions is of crucial importance. In turn, compliance to the exercise intervention is influenced by the supervision on and location of the intervention.

Inconsistent effects on functional abilities, falls, and psychosocial outcomes

No consistent effects of multi-domain interventions on functional abilities, falls or quality of life, psychosocial behavior, or depression were found. However, beneficial effects may have been missed due to a low number of studies examining these outcomes or insufficient power, as several studies did not do a proper sample size calculation for these outcomes or did not include these outcomes as primary outcomes. Previous studies describe improved functional abilities by an exercise intervention but underline the importance that the intervention exercises are functional and task specific (eg, exercising chair rises) in order to improve functional abilities.Citation78,Citation79 Furthermore, recent systematic reviews found conflicting results of the effect of physical activity on quality of life: one review described no consistent effect in elderly with mobility problems, physical disability, and/or multi-morbidity,Citation80 whereas another review described a positive and consistent association in elderly.Citation81

Methodological considerations

Multiple studies were excluded during the study selection, mainly because the authors did not report outcomes stratified by interventions, for example, the Frailty Intervention Trial by Cameron et al.Citation82 These studies, often reporting interdisciplinary team-based approaches, assess affected domains by a comprehensive geriatric assessment and thereafter tailor the treatment to the goals, capacity, and context of the individual.Citation20 As authors did not discriminate between intervention combinations, the interpretability of the effectiveness of the intervention components is inherently impossible.Citation83 The exclusion of these types of articles confines the scope of this review, which was considered reasonable given the goal of the review.

Thanks to the assistance of an expert librarian in the citation, reference and author search, and the inclusion of studies reported in four languages; this review considerably reduced the risk for selection bias. Although the study selection based on title and abstract was done by one reviewer, all relevant articles should have been retrieved as this step was thoroughly performed and in case of doubt, the full article was read and discussed with a second reviewer.

Methodological quality of the included studies ranged from medium to high scores. This indicates that the observed effects are not likely to be overestimated. Moreover, as almost all studies performed poorly with regard to the prospective calculation of the study sample size, the likelihood of type II errors increases, meaning that some nonsignificant results may be falsely considered as nonsignificant. This problem should be addressed in future studies, improving overall study quality.

As the primary focus of this review is to determine the effect of different multi-domain interventions, effects over time within one intervention group were not covered and will not be discussed further. Recent reviews can be consulted for a literature review of these over time effects (eg, Denison et alCitation22).

Remaining and upcoming questions and challenges for future studies

Several questions remain, due to the limited number of studies. First, intervention effects on cognition, social involvement, or some functional outcomes remain unclear, as well as the contribution of several mono-domain interventions (eg, hormonal intervention). Therefore, they should be a focus of future research. Second, the optimal duration of intervention to obtain the effects on frailty status or physical functioning could not be derived due to too small number of studies. Similarly, the persistence of the achieved effects is difficult to discuss as only five studies included follow-up measurements in their study. Third, more studies should examine the ability of the interventions to prevent or treat frailty, as considerable literature describes that multi-domain interventions have this potential.Citation13,Citation16 Essentially, researchers are encouraged to investigate their results from a broader perspective. A core outcome set for these types of studies consisting of following measures is suggested: 1) frailty status, score, and/or characteristics; 2) muscle outcomes (mass and strength); 3) physical outcomes (at least functional abilities and one physical functioning test); 4) cognition, social outcomes, and/or psychological well-being.

In addition, new questions arise. First, heterogeneous populations are considered as (pre)frail elderly as a broad spectrum of frailty screening tools is used in research and clinical practice. Not only were different frailty definitions used, also considerable variety was observed within one type of definition, challenging the generalizability of the intervention. Ultimately, the development of a well-accepted opera-tionalized frailty screening tool will improve homogeneity in study populations and will contribute to the understanding of the results. Second, following questions arise: “What is the optimal moment to tackle frailty by an intervention (preventive or in early pre-frailty stage)?” and “How can participants be motivated to adhere to the intervention program (personal characteristics, program factors, environmental factors)?”

Conclusion

These limited but promising data highlight the potential of the physical exercise component as a standard intervention component, optimally combined with at least a nutritional intervention. Hereby, adequate design of interventions will improve results. Multi-domain interventions were found to be more effective than mono-domain interventions for improving frailty status and physical functioning. Also, a multi-domain intervention tended to yield more positive outcomes for muscle mass and strength. Eventually, understanding the contribution of each mono-domain intervention would pave the way to optimize and prioritize the frailty syndrome management. Finally, diverse frailty definitions cause heterogeneous study populations and urge the development of an overall accepted operationalized frailty definition.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

Marleen Michels participated in the database search. All authors agreed to publish the paper. Funding for this systematic review was provided by internal funding of the University of Leuven, KU Leuven.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WalstonJHadleyECFerrucciLResearch agenda for frailty in older adults: toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older AdultsJ Am Geriatr Soc2006546991100116776798

- GielenEVerschuerenSO’NeillTWMusculoskeletal frailty: a geriatric syndrome at the core of fracture occurrence in older ageCalcif Tissue Int201291316117722797855

- BouillonKKivimakiMHamerMMeasures of frailty in population-based studies: an overviewBMC Geriatr2013136423786540

- Abellan van KanGRollandYHoulesMGillette-GuyonnetSSotoMVellasBThe assessment of frailty in older adultsClin Geriatr Med201026227528620497846

- FriedLTangenCWalstonJFrailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotypeJ Gerontol200156A3M146M156

- SternbergSASchwartzAWKarunananthanSBergmanHClarfieldAMThe identification of frailty: a systematic literature reviewJ Am Geriatr Soc201159112129213822091630

- RockwoodKMitnitskiAFrailty in relation to the accumulation of deficitsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200762772272717634318

- KulminskiAMUkraintsevaSVKulminskayaIVArbeevKGLandKCYashinAICumulative deficits better characterize susceptibility to death in the elderly than phenotypic frailty: lessons from the cardiovascular health studyJ Am Geriatr Soc200856589890318363679

- RizzoliRReginsterJ-YArnalJ-FQuality of life in sarcopenia and frailtyCalcif Tissue Int201393210112023828275

- CollardRMBoterHSchoeversRAOude VoshaarRCPrevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic reviewJ Am Geriatr Soc20126081487149222881367

- SirvenNRappTThe cost of frailty in FranceEur J Health Econ201718224325326914932

- European CommissionMultidimensional Aspects of Population Ageing. Population Ageing in Europe: Facts, Implications and Policies: Outcomes of EU-funded ResearchLuxembourgPublications Office of the European Union2014

- ChenXMaoGLengSXFrailty syndrome: an overviewClin Interv Aging2014943344124672230

- GillTMGahbauerEAAlloreHGHanLTransitions between frailty states among community-living older personsArch Intern Med2006166441842316505261

- XueQLThe frailty syndrome: definition and natural historyClin Geriatr Med201127111521093718

- CameronIDFairhallNGillLDeveloping interventions for frailtyAdv Geriatr201520157

- Gine-GarrigaMRoque-FigulsMColl-PlanasLSitja-RabertMSalvaAPhysical exercise interventions for improving performance-based measures of physical function in community-dwelling, frail older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysisArch Phys Med Rehabil2014954753.e3769.e324291597

- CadoreELRodriguez-ManasLSinclairAIzquierdoMEffects of different exercise interventions on risk of falls, gait ability, and balance in physically frail older adults: a systematic reviewRejuvenation Res201316210511423327448

- CermakNMResPTde GrootLCSarisWHvan LoonLJProtein supplementation augments the adaptive response of skeletal muscle to resistance-type exercise training: a meta-analysisAm J Clin Nutr20129661454146423134885

- FairhallNLangronCSherringtonCTreating frailty – a practical guideBMC Med201198321733149

- VliekSMelisRJFaesMSingle versus multicomponent intervention in frail elderly: simplicity or complexity as precondition for success?J Nutr Health Aging200812531932218443714

- DenisonHJCooperCSayerAARobinsonSMPrevention and optimal management of sarcopenia: a review of combined exercise and nutrition interventions to improve muscle outcomes in older peopleClin Interv Aging20151085986925999704

- DanielsRvan RossumEde WitteLKempenGvan den HeuvelWInterventions to prevent disability in frail community-dwelling elderly: a systematic reviewBMC Health Serv Res2008827819115992

- SchneiderNYvonCA review of multidomain interventions to support healthy cognitive ageingJ Nutr Health Aging201317325225723459978

- BibasLLeviMBendayanMMullieLFormanDEAfilaloJTherapeutic interventions for frail elderly patients: part I. Published randomized trialsProg Cardiovasc Dis201457213414325216612

- Porter StarrKNMcDonaldSRBalesCWObesity and physical frailty in older adults: a scoping review of lifestyle intervention trialsJ Am Med Dir Assoc201415424025024445063

- BeswickADReesKDieppePComplex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people: a systematic review and meta-analysisLancet2008371961472573518313501

- DanielsRMetzelthinSvan RossumEde WitteLvan den HeuvelWInterventions to prevent disability in fail community-dwelling older persons: an overviewEur J Ageing201073755

- LeePHLeeYSChanDCInterventions targeting geriatric frailty: a systemic reviewJ Clin Gerontol Geriatr2012324752

- LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJThe PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaborationBMJ2009339b270019622552

- SlimKNiniEForestierDKwiatkowskiFPanisYChipponiJMethodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrumentANZ J Surg200373971271612956787

- ChanDCTsouHHYangRSA pilot randomized controlled trial to improve geriatric frailtyBMC Geriatr2012125823009149

- ChinAPawMJde JongNSchoutenEGHiddinkGJKokFJPhysical exercise and/or enriched foods for functional improvement in frail, independently living elderly: a randomized controlled trialArch Phys Med Rehabil200182681181711387588

- ChinAPawMJde JongNSchoutenEGvan StaverenWAKokFJPhysical exercise or micronutrient supplementation for the wellbeing of the frail elderly? A randomised controlled trial [with consumer summary]Br J Sports Med200236212613111916896

- de JongNSensible aging: using nutrient-dense foods and physical exercise with the frail elderlyNutr Today2001364202207

- de JongNChinAPMJde GrootLCHiddinkGJvan StaverenWADietary supplements and physical exercise affecting bone and body composition in frail elderly personsAm J Public Health200090694795410846514

- de JongNChinAPMJde GraafCvan StaverenWAEffect of dietary supplements and physical exercise on sensory perception, appetite, dietary intake and body weight in frail elderly subjectsBr J Nutr200083660561310911768

- de JongNChinAPMJde GrootLCde GraafCKokFJvan StaverenWAFunctional biochemical and nutrient indices in frail elderly people are partly affected by dietary supplements but not by exerciseJ Nutr1999129112028203610539780

- ChinAPawMJde JongNPallastEGMKloekGCSchoutenEGKokFJImmunity in frail elderly: a randomized controlled trial of exercise and enriched foodsMed Sci Sports Exerc200032122005201111128843

- de JongNChinAPMJde GrootLCNutrient-dense foods and exercise in frail elderly: effects on B vitamins, homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, and neuropsychological functioningAm J Clin Nutr200173233834611157333

- HennesseyJVChromiakJAdella VenturaSGrowth hormone administration and exercise effects on muscle fiber type and diameter in moderately frail older peopleJ Am Geriatr Soc200149785285811527474

- KennyAMBoxerRSKleppingerABrindisiJFeinnRBurlesonJADehydroepiandrosterone combined with exercise improves muscle strength and physical function in frail older womenJ Am Geriatr Soc20105891707171420863330

- KimHSuzukiTKimMEffects of exercise and milk fat globule membrane (MFGM) supplementation on body composition, physical function, and hematological parameters in community-dwelling frail Japanese women: a randomized double blind, placebo-controlled, follow-up trialPLoS One2015102e011625625659147

- KwonJYoshidaYYoshidaHKimHSuzukiTLeeYEffects of a combined physical training and nutrition intervention on physical performance and health-related quality of life in prefrail older women living in the community: a randomized controlled trialJ Am Med Dir Assoc2015163261268

- NgTPFengLNyuntMSNutritional, physical, cognitive, and combination interventions and frailty reversal among older adults: a randomized controlled trialAm J Med2015128111225.e11236.e126159634

- RydwikELammesEFrandinKAknerGEffects of a physical and nutritional intervention program for frail elderly people over age 75. A randomized controlled pilot treatment trialAging Clin Exp Res200820215917018431084

- RydwikEFrandinKAknerGEffects of a physical training and nutritional intervention program in frail elderly people regarding habitual physical activity level and activities of daily living – a randomized controlled pilot studyArch Gerontol Geriatr201051328328920044155

- RydwikEGustafssonTFrandinKAknerGEffects of physical training on aerobic capacity in frail elderly people (75+ years). Influence of lung capacity, cardiovascular disease and medical drug treatment: a randomized controlled pilot trialAging Clin Exp Res2010221859420305369

- LammesERydwikEAknerGEffects of nutritional intervention and physical training on energy intake, resting metabolic rate and body composition in frail elderly. A randomised, controlled pilot studyJ Nutr Health Aging201216216216722323352

- TielandMDirksMLvan der ZwaluwNProtein supplementation increases muscle mass gain during prolonged resistance-type exercise training in frail elderly people: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialJ Am Med Dir Assoc201213871371922770932

- van de RestOvan der ZwaluwLTielandMEffect of resistance-type exercise training with or without protein supplementation on cognitive functioning in frail and pre-frail elderly: secondary analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialMech Ageing Dev2014136–1378593

- DornerTELackingerCHaiderSNutritional intervention and physical training in malnourished frail community-dwelling elderly persons carried out by trained lay “buddies”: study protocol of a randomized controlled trialBMC Public Health201313123224369785

- LugerEDornerTEHaiderSKapanALackingerCSchindlerKEffects of a home-based and volunteer-administered physical training, nutritional, and social support program on malnutrition and frailty in older persons: a randomized controlled trialJ Am Med Dir Assoc2016177671.e9671.e16

- Tarazona-SantabalbinaFGomez-CabreraMPerez-RosPA multicomponent exercise intervention that reverses frailty and improves cognition, emotion, and social networking in the community-dwelling frail elderly: a randomized clinical trialJ Am Med Dir Assoc201617542643326947059

- IkedaTAizawaJNagasawaHEffects and feasibility of exercise therapy combined with branched-chain amino acid supplementation on muscle strengthening in frail and pre-frail elderly people requiring long-term care: a crossover trialAppl Physiol Nutr Metab201641443844526963483

- de LabraCGuimaraes-PinheiroCMasedaALorenzoTMillan-CalentiJCEffects of physical exercise interventions in frail older adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trialsBMC Geriatr20151515426626157

- MalafarinaVUriz-OtanoFIniestaRGil-GuerreroLEffectiveness of nutritional supplementation on muscle mass in treatment of sarcopenia in old age: a systematic reviewJ Am Med Dir Assoc2013141101722980996

- MakanaeYFujitaSRole of exercise and nutrition in the prevention of sarcopeniaJ Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo)201561SupplS125S12726598823

- BosaeusIRothenbergENutrition and physical activity for the prevention and treatment of age-related sarcopeniaProc Nutr Soc201675217418026620911

- VolpiENazemiRFujitaSMuscle tissue changes with agingCurr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care20047440541015192443

- PerkisasSDe CockAVerhoevenVVandewoudeMPhysiological and architectural changes in the ageing muscle and their relation to strength and function in sarcopeniaEur Geriatr Med201673201206

- AguirreLEVillarealDTPhysical exercise as therapy for frailtyNestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser201583839226524568

- CadoreELCasas-HerreroAZambom-FerraresiAMulticomponent exercises including muscle power training enhance muscle mass, power output, and functional outcomes in institutionalized frail nonagenariansAge (Dordr)201436277378524030238

- RejeskiWJMihalkoSLPhysical activity and quality of life in older adultsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200156Spec2233511730235

- MuraGCartaMGPhysical activity in depressed elderly a systematic reviewClin Pract Epidemiol Mental Health20139125135

- BhererLEricksonKILiu-AmbroseTA review of the effects of physical activity and exercise on cognitive and brain functions in older adultsJ Aging Res201320138

- TheouOStathokostasLRolandKPThe effectiveness of exercise interventions for the management of frailty: a systematic reviewJ Aging Res2011201156919421584244

- NashKCMThe effects of exercise on strength and physical performance in frail older people: a systematic reviewRev Clin Gerontol2012224274285

- EdingtonJKonPMartynCNPrevalence of malnutrition in patients in general practiceClin Nutr1996152606316843999

- BonnefoyMBerrutGLesourdBFrailty and nutrition: searching for evidenceJ Nutr Health Aging201519325025725732208

- BartaliBFrongilloEABandinelliSLow nutrient intake is an essential component of frailty in older personsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200661658959316799141

- DeutzNEBauerJMBarazzoniRProtein intake and exercise for optimal muscle function with aging: recommendations from the ESPEN Expert GroupClin Nutr201433692993624814383

- BauerJMDiekmannRProtein supplementation with agingCurr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care2015181243125474010

- HicksonMNutritional interventions in sarcopenia: a critical reviewProc Nutr Soc201574437838625923603

- BauerJBioloGCederholmTEvidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study GroupJ Am Med Dir Assoc201314854255923867520

- WallBCermakNLoonLDietary protein considerations to support active agingSports Med201444185194

- KobayashiSAsakuraKSugaHSasakiSHigh protein intake is associated with low prevalence of frailty among old Japanese women: a multicenter cross-sectional studyNutr J20131216424350714

- Gine-GarrigaMGuerraMPagesEManiniTMJimenezRUnnithanVBThe effect of functional circuit training on physical frailty in frail older adults: a randomized controlled trialJ Aging Phys Act201018440142420956842

- SkeltonDAYoungAGreigCAMalbutKEEffects of resistance training on strength, power, and selected functional abilities of women aged 75 and olderJ Am Geriatr Soc19954310108110877560695

- de VriesNMvan RavensbergCDHobbelenJSOlde RikkertMGStaalJBNijhuisvan der SandenMWEffects of physical exercise therapy on mobility, physical functioning, physical activity and quality of life in community-dwelling older adults with impaired mobility, physical disability and/or multi-morbidity: a meta-analysisAgeing Res Rev201211113614922101330

- VagettiGCBarbosa FilhoVCMoreiraNBOliveiraVMazzardoOCamposWAssociation between physical activity and quality of life in the elderly: a systematic review, 2000–2012Rev Bras Psiquiatr2014361768824554274

- CameronIDFairhallNLangronCA multifactorial interdisciplinary intervention reduces frailty in older people: randomized trialBMC Med2013116523497404

- FairhallNSherringtonCKurrleSELordSRLockwoodKCameronIDEffect of a multifactorial interdisciplinary intervention on mobility-related disability in frail older people: randomised controlled trialBMC Med20121012023067364

- RockwoodKSongXMacKnightCA global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly peopleCMAJ2005173548949516129869

- ChanDCTsouHHChenCYChenCYValidation of the Chinese-Canadian study of health and aging clinical frailty scale (CSHA-CFS) telephone versionArch Gerontol Geriatr2010503e74e8019608288

- TaylorHLJacobsDRJrSchuckerBKnudsenJLeonASDebackerGA questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activitiesJ Chronic Dis19783112741755748370

- ChinAPawMJDekkerJMFeskensEJMSchoutenEGKromhoutDHow to select a frail elderly population? A comparison of three working definitionsJ Clin Epidemiol199952111015102110526994

- Mattiasson-NiloISonnUJohannessonKGosman-HedstromGPerssonGBGrimbyGDomestic activities and walking in the elderly: evaluation from a 30-hour heart rate recordingAging (Milano)1990221911982095860

- FrändinKGrimbyGAssessment of physical activity, fitness and performance in 76-year-oldsScand J Med Sci Sports1994414146

- ReubenDBSiuALAn objective measure of physical function of elderly outpatients. The Physical Performance TestJ Am Geriatr Soc19903810110511122229864

- Romero-OrtunoRWalshCDLawlorBAKennyRAA frailty instrument for primary care: findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE)BMC Geriatr2010105720731877