Abstract

Background

The number of clinical trials including older patients, and particularly patients with cognitive impairment, is increasing. While statutory provisions exist to make sure that the capacity to consent is assessed systematically for each patient, many gray areas remain with regard to how this assessment is made or should be made in the routine practice of clinical research.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to draw up an inventory of assessment tools evaluating older patients’ capacity to consent specifically applicable to clinical research, which could be used in routine practice.

Methods

Two authors independently searched PubMed, Cochrane, and Google Scholar data-bases between November 2015 and January 2016. The search was actualized in April 2017. We used keywords (MeSH terms and text words) referring to informed consent, capacity to consent, consent for research, research ethics, cognitive impairment, vulnerable older patients, and assessment tools. Existing reviews were also considered.

Results

Among the numerous existing tools for assessing capacity to consent, 14 seemed potentially suited for clinical research and six were evaluated in older patients. The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR) was the most frequently cited.

Conclusion

The MacCAT-CR is currently the most used and the best validated questionnaire. However, it appears difficult to use and time-consuming. A more recent tool, the University of California Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent (UBACC), seems interesting for routine practice because of its simplicity, relevance, and applicability in older patients.

Introduction

The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related disorders in the context of aging demographics is a major public health issue.Citation1 Dementia leads to several functional alterations responsible for a loss of bearings in time and space and impairment of the patients’ capacity to perform activities of daily living or express their will without assistance.Citation2,Citation3 This progressive loss of autonomy drastically affects the life of patients (and those around them), making them vulnerable and reducing their quality of life.

One of the most important components of vulnerability in patients with cognitive decline is the loss of capacity to make decisions. This can progressively affect various domains of their everyday life and have implications in the legal or medical fields.Citation3,Citation4 The impairment of decisional capacity (DC) raises many questions for the patients’ relatives or professional caregivers. According to a recent literature review, the prevalence of such impairment could reach 34% of hospitalized patients and up to 45% of patients in psychiatric settings.Citation5

In the case of alteration of their DC, the patients can easily find themselves deprived of fundamental rights. There is also a risk that they end up making decisions against their interest without realizing it. The loss of DC can, thus, affect the patients’ autonomy and make them dependent on external help. Conversely, the DC of patients with mild cognitive impairment may also be excessively underestimated.Citation6,Citation7 In either situation, the potential legal or ethical consequences are considerable.Citation3,Citation4

The field of clinical research is especially exposed to these risks. In spite of the existing bioethics laws and regulations designed to protect patients taking part in research,Citation8,Citation9 the means by which the inclusions to clinical trials are made can sometimes be put into question, especially regarding the evaluation of the patient’s capacity to consent for research (CR). When the CR is in doubt, it is therefore common to consult a close relative such as the patient’s support person, but there again, the means by which this person should be designated remain unclear, and the reliability of such surrogate consent is most often questionable.Citation10–Citation15

Various theoretical concepts have been developed for use in conceptualizing decision making specifically in informed consent contexts, merging from the fields of neuropsychiatry, psychology, sociology, or behavioral science.Citation16 In the cognitive models, the consensus is that decision making is based on four different aptitudes.Citation17–Citation19 The patients need 1) to be able to understand the information and issues of the decision (comprehension), 2) to realize that the decision to be made applies to themselves and to personalize their decision in line with intimate values or beliefs (appreciation), 3) to be able to evaluate different alternatives and their consequences (reasoning), and 4) to communicate on a decision (choice). Furthermore, emotion and social factors also take a strong part in decision making.Citation16,Citation20,Citation21 Short-term and semantic memory affect all four abilities but are more strongly associated with understanding and reasoning.Citation22,Citation23 Executive functions, which cover important domains such as attention, encoding of verbal and visual material, forward planning, organization, and cognitive flexibility, are also critical to decision making. They can be impacted even in early stages of AD- or Parkinson’s disease-related cognitive impairment and alter understanding, appreciation, and reasoning.Citation24,Citation25 Finally, the expression of a choice can be influenced by language or behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms such as apathy.Citation26

There are two ways to assess DC in informed consent situations: assess cognitive capacities and their impairment (eg, mental status examinations and neuropsychological instruments) and assess capacities as demonstrated within the context of content that is specific to the consent situation. However, usual global screening tests such as Folstein’s mini–mental state examination (MMSE)Citation27 are indirect and, therefore, imperfect ways of inferring what a person might do if faced with the task of understanding or reasoning about being in a clinical trial study.Citation28,Citation29 Consequently, an objective and direct evaluation of patients’ DC, in case of doubt as to the validity of the consent, ensures that the inclusion of subjects to clinical trials is ethical and respectful of their rights, which is the responsibility of researchers. However, it can be observed that research protocols are often vague on the means used to assess CR, suggesting that overall awareness of professionals and researchers, including those working in the field of dementia, is insufficient.

Previous reviews have essentially been focused on capacity to consent to treatment. Reviews focusing specifically on capacity to consent to research are scarce and seemed to have yielded only a few results in comparison to the numerous tools developed, especially in the psychiatric context.Citation30,Citation31 The aim of this review was to draw up an inventory of assessment instruments for evaluating the DC of older patients with cognitive impairment, which could be specifically applicable to the assessment of the CR.

Methods

Two authors (TG and OLS) independently consulted PubMed (Medline), Google Scholar, and the Cochrane databases in search for original articles describing tools for the assessment of DC. Existing literature reviews on the topic were also considered as additional information. The initial search was conducted between November 2015 and January 2016 and was actualized in April 2017.

The inclusion criteria were based on the tools themselves. To be included, the references had to make a description of tests specifically designed for assessing patients’ DC, with a report of the methods for assessing validity and/or reliability (either from the original report or from other studies evaluating the same test). Second, a mention of applicability to research and to older people with cognitive impairment was sought.

Different search strategies were performed using in priority keywords from the MeSH thesaurus: “informed consent”, “decision making”, “neuro-cognitive disorders”, “aged”, “adult clinical protocols”, and “research subjects”. However, the following additional keywords completed the search strategy: “Alzheimer”, “dementia”, “protocol inclusion”, “ethics”, “consent for research”, “consent to research”, “inclusion in clinical trials”, “competency”, “capacity to consent”, “understanding”, and “neuro-psychological evaluation”. No language or publication date limit was set.

The article selection was based on titles, abstracts, and finally full text for relevant articles. Additional results were also retrieved from the bibliography of existing reviews. Second, the same two authors independently conducted the data extraction and the selection of suitable tests or tools for assessing patients’ CR. Finally, the results were combined, and consensus was reached through discussion between authors.

Results

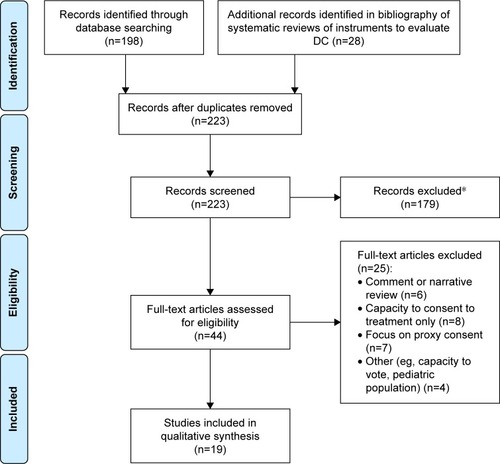

The flow diagram in summarizes the number of articles accepted and rejected during the selection procedure. The search of the computerized databases identified a total of 226 articles. In the end, a total of 19 publications were identified as relevant to our research on instruments assessing DC for patients with cognitive disorders (). In addition, six literature reviews of instruments to evaluate CR were also considered as complementary information.Citation30–Citation35

Figure 1 Flow chart of search results.

Abbreviation: DC, decision capacity.

Thirty-eight instruments assessing DC were identified. However, the vast majority of existing tests were developed to assess the capacity of patients to consent to medical treatment and not for research purpose. For this particular context, 14 assessment tools were identified, the majority of which were initially developed or validated in psychiatric populations.Citation30,Citation32,Citation34 The main characteristics of each test are summarized in . They differ by the method used (eg, self-administered questionnaire and structured interview), the abilities assessed (among the four dimensions of decision making), the population they were initially aimed for (sometimes focused on very specific populations), the administration time, and the robustness of their evaluation (validity and reliability) ().

Table 1 Summary of included assessment tools (presented by year of publication)

In older patients with cognitive disorders, the following six tests have been evaluated, with variable consistency: the vignette method by Schmand et al,Citation36 the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR),Citation37 the evaluation to sign consent (ESC),Citation38 the brief informed consent test,Citation39 the University of California Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent (UBACC) questionnaire,Citation40 and the older adults’ capacity to consent to research (OACCR).Citation41 These tools are described briefly hereafter in chronological order.

ESC

The ESC is a short questionnaire tailored to the research protocol.Citation38 The ESC presents the advantage of being short and simple to use. The patient reflects his understanding of the protocol by answering five questions, four of which require the assessor to make subjective judgments of the patient’s capacity. However, the three other dimensions of DC assessment are not covered by this test. Furthermore, the evaluation may be at risk of examiner bias, as the scoring mainly relies on the subjective judgment of the examiner, without any explicit cutoff. The ESC was initially tested in schizophrenia and HIV patients but has also been evaluated in 346 older nursing home residents.Citation42

Vignettes method developed by Schmand et al

This method was developed in the 1990s and evaluated in aged Dutch people (70–90 years), who were cognitively intact (n=176) or had dementia (n=64; mostly AD).Citation36 Two vignettes were used as competency assessment instruments. A vignette is a description of an imaginary situation in which the subject is asked to decide on a proposed treatment or on participation in research. His/her understanding of the situation and the quality of the reasoning underlying that choice are tested by a short series of questions. The answers to the vignette questions were summed to form a competency score. The reliability (internal consistency) of this score was 0.82 for both vignettes combined. However, when assessing agreement between Schmand’s vignette method and a physician’s judgment in the group of patients with dementia, Cohen’s kappa was only of 0.36 (fair agreement) and dropped to 0.04 (no agreement) when patients with “minimal dementia” were left out of the analysis.

MacCAT-CR

The MacCAT-CR was the most frequently cited existing tool, often referred to and used as a reference to assess capacity to consent to research and test the validity of other toolsCitation37 as it is the most widespread and the most validated of all.Citation3,Citation30,Citation32,Citation43–Citation45 It is a modified version of the MacCAT-T used to assess the capacity to consent to treatment.Citation46 This is a 21-item structured interview with four subscales assessing the following four main dimensions of decision making: understanding, appreciation, reasoning, and expressing a choice. Each subscore is predictive of decision-making capacity. Thirteen questions are dedicated to understanding, three questions are dedicated to appreciation, four questions are dedicated to reasoning, and one question is dedicated to expressing a choice. Each item is scored 0 (inadequate), 1 (partially adequate), or 2 (adequate). Questions are tailored to the specific research context in which the patient is asked to participate. This test was developed in a wide variety of clinical situations and for different populations. Yet, the reliability and validation of derived versions are less established.Citation30 In particular, two groups of researchers adapted this test for use in patients with AD, in which they suggested dummy clinical trial protocols.Citation44,Citation47 The test comes with a user’s guide and a precise rating manual. However, there is no threshold or limit score that would directly discriminate patients able to decide from those who are not. Rather, this tool was conceived as an aid to be used by the assessor for the appreciation of DC.Citation30 The other downsides of this test are its relative complexity, the need for specific training, the absence of specific cutoff scores, and the duration of the test of ~20 minutes, which could also be a barrier in the process of patient inclusions to clinical trials.Citation30,Citation48

Brief informed consent test

This test was constructed to address the following eight elements of informed consent as stated in the Code of Federal Regulations:Citation9 1) explanation of the purposes of the research and the requirements of participation; 2) description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts to the participant; 3) description of any benefits to the participant or to others; 4) disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment; 5) statement describing the extent, if any, to which confidentiality of records identifying the participant will be maintained; 6) for research involving more than minimal risk, an explanation/information as to whether any medical treatments are available if injury occurs; 7) contact information for the study investigator in the event of a research related injury to the participant and for questions; and 8) a statement that participation is voluntary and that refusal to participate will involve no penalty or loss of benefits. After a review process by ethical and research committees, 11 items were selected and closed-ended questions were used. This test shows only moderate correlation with the Clinical Dementia Rating scale () and was not evaluated against psychiatric expertise or other specific DC tools such as the MacCAT-CR.Citation39

UBACC

UBACC is a 10-item questionnaire.Citation40 This test uses a pragmatic approach using a teach-back process of the protocol and the potential risks and benefits of participating. The total score is determined by the accuracy of answers depending on expected answers for each question. It has the advantage of being short and does not require specific training. It can be tailored specifically to the clinical trial proposed to the patient. Yet, this tool does not evaluate the capacity to express a choice.Citation43 A validation study showed good performances of the UBACC in terms of external and internal validity, reliability, sensitivity, and specificity.Citation40 Although initially developed for all vulnerable patients, including those with schizophrenia, it has also shown promise in AD patients and showed good correlation with cognitive features such as verbal fluency and global cognition.Citation49 However, expression of a choice is not evaluated by this test. It has been translated and validated in different languages and should soon be recommended by European regulatory authorities.Citation48,Citation50,Citation51

OACCR

The OACCR was developed in nursing home residents and community dwelling older adults in South Korea.Citation41 It was designed to cover the four dimensions of decision making with a short questionnaire of only four open questions. The strength of this questionnaire relies in its simplicity, which could make it interesting for use in routine practice. However, one could think such a simple test might not be enough to evaluate the complexity of the assessment of DC, and the validation procedure seems still insufficient, especially with regard to the gold standard chosen as reference. Rather than testing the correlation to psychiatric expertise or the MacCAT-CR (despite limitations enounced earlier), the authors have preferred to use the capacity-to-consent screen by Zayas et al,Citation52 a test which is a less validated test.Citation31 Finally, it is not clear whether an English version has been evaluated.

Discussion

In this study, we searched existing tools for assessing older patients’ DC in the context of clinical research. Five reviews were identified.Citation30,Citation32–Citation34,Citation43 During our search, we listed 13 assessment tests specifically designed to evaluate the patients’ capacity to consent to be included in a research protocol. Two of these appeared particularly relevant to us: the MacCAT-CRCitation37 and the UBACC.Citation40 No new instruments were identified as having been developed in the past 6 years, and only two of the 14 were developed in the past 10 years.

While physiological aging does not normally affect communication and DC,Citation34,Citation48 many incident pathologies in aging, such as a decrease in sensory acuity, depression, stroke (especially in the case of aphasia), and of course dementia, can have a serious impact on DC.

There is no debate over the strong impairment of DC in severe stages of AD.Citation28,Citation53,Citation54 Moreover, in the case of mild-to-moderate disease, many studies suggest that DC can be affected even at the early stages of cognitive decline.Citation33,Citation53,Citation55–Citation59 Understanding capacities would be affected the earliest, followed by reasoning and appreciation, while the capacity of choice would be preserved the longest.Citation58,Citation60 Indeed, understanding is mainly affected by an impairment of episodic and semantic memory, whereas reasoning and appreciation depend on both memory and executive functions.Citation23–Citation25,Citation55,Citation57

Another particularity is that AD is often accompanied by anosognosia. Lack of awareness could alter the patient’s capacity to anticipate and weigh the possible consequences of a decision or action (reasoning and appreciation). Patients may also paradoxically be able to reason situations for others but not as well for themselves. Lack of awareness is correlated with disease severity but can affect patients at an early stage. Some authors suggest using specific tests for anosognosia (such as the Anosognosia Questionnaire for DementiaCitation61) when judging on a patient’s competence, as awareness and DC could be affected differently in patients with cognitive impairment.Citation62

Many clinicians or researchers use their clinical impression or Folstein’s MMSECitation27 to give an opinion on the patients’ DC. This attitude seems appealing, as it means there is no need for complementary investigations. In comparison with psychiatric expertise, this approach appears however imprecise.Citation29,Citation63 The interpretation of the results and the norms depend on the level of education of the patient and can thus vary from one patient to the an other.Citation64 Additionally, besides extreme values, the MMSE score is not sufficiently reliable to evaluate the patients’ comprehension and judgment ability.Citation28,Citation29 Moreover, there can be differences between individuals for a given MMSE score, and discrepancies can exist between the global assessment of cognitive functions and the DC of the patients as assessed by more specific evaluations.Citation7,Citation30 To a certain extent, this implies that the DC of patients can be affected, although the cognitive impairment remains mild, or oppositely, that the DC can sometimes be underestimated when the cognitive tests show greater impairment. Kim and CaineCitation28 have studied the reliability of Folstein’s MMSE to assess DC, in comparison to the MacCAT-CR, used as a reference. They concluded that MMSE was not a good predictor of incompetence. However, this test could still be useful if using two different thresholds: a score of >26 had a high sensitivity of 96%–100% to detect competent patients while a score of <19 had a specificity of 85%–94%.Citation28 The authors suggested that a score of >26 on the MMSE would allow to safely identify competent subjects with no need for further investigation.Citation65 In another study, Pucci et alCitation66 found that an MMSE score of ≤17 had a positive predictive value of incompetence of 95%, while only ~63% of patients above this threshold were rated sufficiently competent. Therefore, for patients with mild cognitive impairment (with MMSE values between 17 and 26), a gray area remains, with the need for more precise and specific assessment tools.

Standardized tools for assessing DC started to be developed in the 1990s.Citation67 We observed that the large majority of tests were developed to evaluate the patients’ capacity to consent to a medical treatment or other everyday life situations, especially in the field of psychiatry.Citation20 However, there are some heterogeneities between schizophrenia and dementia with regard to DCCitation68 and clinical research is also a very specific domain. The distinction between consent to treatment and consent to research needs to be underlined. In the context of clinical trials, the patients need to be able to understand the aims of the research and other particularities such as randomization, the use of placebos, and the fact that they might not benefit from the treatment.Citation69 Patients with mild cognitive impairment may present with low understanding of the design, potential benefits, and risks of the study.Citation70 In fact, depending on the criteria considered, very few patients would be considered actually capable of giving consent with regard to the thresholds of the specific tests.Citation55,Citation60,Citation68 However, patients with mild cognitive impairment remain able to participate in decisions affecting themselves.Citation12,Citation71 Among the numerous existing tests, only someCitation36,Citation40,Citation51,Citation72,Citation74,Citation75 enable simultaneous evaluation of the four dimensions of decision making (comprehension, choice, reasoning, and appreciation). Most of the tests only evaluate comprehension, while others are designed to evaluate other dimensions more specifically. Also, some tests explore certain components of understanding that are not studied by others. The notion of double blind is, for example, evaluated by the MacCAT-CR but not by the UBACC.

Another difficulty is that, during the evaluation of each tool, discrepancies in the evaluation of DC were found between the results of the tests and the point of view of experts.Citation30 Such differences could cause important interpretation problems and complicate the development of assessment tools. For example, Schmand et alCitation36 have described a very low agreement between there vignette method and physicians’ assessment (kappa =0.04–0.36) of capacity. While this initially appears like a flaw in the test’s reliability, the authors attributed this to a lack of consistency of the subjective clinical evaluation and used this argument to warrant the use of their method.Citation36 Both psychiatric expertise and the large majority of assessment tools rely on subjective interpretation. This highlights the major difficulties of developing a reliable tool in the absence of an indisputable gold-standard evaluation. Many tools have been developed using the MacCAT-CR as a reference. Indeed, it is the most widely employed instrument and recognized as the most validated and reliable in this population.Citation45 However, it has limitations as a gold standard because it does not have a specific objective cut-point (clinical decision making is still required for interpretation) and was developed with reference to psychiatric expertise, which also lacks consistency. As there is currently no clear diagnostic reference to compare the reviewed diagnostic tests to, it becomes impossible to assess sensitivity and specificity of measures; this is also the main reason why the Cochrane systematic project was withdrawn from publication.Citation35 Furthermore, DC is ultimately a legal construct, which depends mainly on the external evaluation and also remains subjective, despite efforts toward standardization of procedures.

In this difficult context, the evaluation of interrater reliability appears very important, but this information was unfortunately lacking for six out of the 14 tests presented in . Among the six tools evaluated in the cognitively impaired geriatric population, interrater reliability was reported for only four and could be as low as 0.59 as for the OACCR.Citation41

Following validation works from Kim et alCitation47 and Karlawish et al,Citation44 the MacCAT-CR can be applicable to the particular context of AD. However, in both of these studies, the MacCAT-CR tended to underestimate the patients’ competency to decide, as compared to the judgment of experts.Citation32,Citation44,Citation47 This could suggest that the MacCAT-CR is too “severe” for this type of population. However, this finding needs to be put into perspective, as it could also be argued conversely that the experts have overestimated the patients’ competency, illustrating there again the interpretation problems due to the lack of a clear gold standard. In a study aiming to compare the DC of patients with schizophrenia and dementia, the same authors have developed a short three-item questionnaire derived from the understanding subscale of the MacCAT-CR, focused on understanding the purpose, risks, and benefits of the protocol.Citation68 For a cut-point of 2.5, this simplified tool achieved a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 77.3% for detecting impaired understanding using the understanding subscale of the MacCAT-CR.Citation68 Such an approach could potentially help to rapidly discriminate patients with need for further assessment and make use of the MacCAT-CR more practical. However, this three-item questionnaire was only developed for the purpose of this study and would need further evaluation to be considered as a potential tool to be used independently.

Due to the prevalence of cognitive decline and multiple comorbidities in this population, older patients have, until recently, rarely been included in clinical trials – even though this age group accounts for a majority of overall medication consumption.Citation72 Currently, clinical trials specifically oriented to aged patients are multiplying, especially in the field of dementia research. However, these studies are often forced to limit the inclusions to patients at very early and mild stages of the disease.Citation73 Scientific progress requires that clinical trials can be carried out and that potentially vulnerable patients can take part in the research in the most ethical and considerate way. Moreover, it appears important that patients recruited in clinical trials are representative of the target population. In order to improve the ethics of patient inclusion without altering participation rates to clinical trials, valid consent procedures are needed. In the event of incompetence, the means by which surrogate consent is used and the way the proxy is designated remain unclear.Citation14,Citation15,Citation74,Citation75 Finally, the awareness among professionals and researchers on this issue needs to be raised. Project reviewers and ethical boards should give particular focus to the procedures for patient inclusion when reviewing study protocols.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LoboALaunerLJFratiglioniLPrevalence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research GroupNeurology20005411 suppl 5S4S910854354

- TraykovLRigaudA-SCesaroPBollerFLe déficit neuropsychologique dans la maladie d’Alzheimer débutante. [Neuropsychological impairment in the early Alzheimer’s disease]L’Encéphale2007333 pt 1310316

- KarlawishJMeasuring decision-making capacity in cognitively impaired individualsNeurosignals2008161919818097164

- WelieSPCriteria for patient decision making (in)competence: a review of and commentary on some empirical approachesMed Health Care Philos20014213915111547500

- LeppingPStanlyTTurnerJSystematic review on the prevalence of lack of capacity in medical and psychiatric settingsClin Med Lond Engl2015154337343

- GanziniLVolicerLNelsonWDerseAPitfalls in assessment of decision-making capacityPsychosomatics200344323724312724505

- PalmerBWHarmellALPintoLLDeterminants of capacity to consent to research on Alzheimer’s diseaseClin Gerontol2017401243428154452

- WMA [webpage on the Internet]The Helsinki Statement1964 Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/Accessed July 27, 2017

- Code of Federal Regulations [webpage on the Internet]Title 21. Section 50.25. Informed consent of Human Subjects2016 Available from: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=aef4d60308e79aaacf3283747dc38c59&mc=true&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title21/21cfr50_main_02.tplAccessed July 27, 2017

- KimSYHKimHMLangaKMKarlawishJHTKnopmanDSAppelbaumPSSurrogate consent for dementia research: a national survey of older AmericansNeurology200972214915519139366

- MoyeJSabatinoCPWeintraub BrendelREvaluation of the capacity to appoint a healthcare proxyAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201321432633623498379

- BlackBSWechslerMFogartyLDecision making for participation in dementia researchAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201321435536323498382

- KimSYHKarlawishJHKimHMWallIFBozokiACAppelbaumPSPreservation of the capacity to appoint a proxy decision maker: implications for dementia researchArch Gen Psychiatry201168221422021300949

- KimSYHKimHMRyanKAHow important is “accuracy” of surrogate decision-making for research participation?PLoS One201381e5479023382969

- De VriesRRyanKAStanczykAPublic’s approach to surrogate consent for dementia research: cautious pragmatismAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201321436437223498383

- LeeDNeural basis of quasi-rational decision makingCurr Opin Neurobiol200616219119816531040

- AppelbaumPSRothLHCompetency to consent to research: a psychiatric overviewArch Gen Psychiatry19823989519587103684

- BergJWAppelbaumPSGrissoTConstructing competence: formulating standards of legal competence to make medical decisionsRutgers Law Rev199648234537116086484

- SaksERJesteDVCapacity to consent to or refuse treatment and/or research: theoretical considerationsBehav Sci Law200624441142916883609

- ABA/APA. American Bar Association/American Psychologists AssociationAssessment of Older Adults with Diminished Capacity: A Handbook for PsychologistsWashington, DCABA, APA2008

- BecharaADamasioHDamasioAREmotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortexCereb Cortex200010329530710731224

- MoyeJKarelMJGurreraRJAzarARNeuropsychological predictors of decision-making capacity over 9 months in mild-to-moderate dementiaJ Gen Intern Med2006211788316423129

- StormoenSAlmkvistOEriksdotterMSundströmETallbergI-MCognitive predictors of medical decision-making capacity in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry201429121304131124737535

- MoelterSTWeintraubDMaceLResearch consent capacity varies with executive function and memory in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord201631341441726861463

- SchillerstromJERickenbackerDJoshiKGRoyallDRExecutive function and capacity to consent to a noninvasive research protocolAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200715215916217272736

- BertrandEvan DuinkerkenELandeira-FernandezJBehavioral and psychological symptoms impact clinical competence in Alzheimer’s diseaseFront Aging Neurosci2017918228670272

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res19751231891981202204

- KimSYHCaineEDUtility and limits of the mini mental state examination in evaluating consent capacity in Alzheimer’s diseasePsychiatr Serv200253101322132412364686

- WarnerJMcCarneyRGriffinMHillKFisherPParticipation in dementia research: rates and correlates of capacity to give informed consentJ Med Ethics200834316717018316457

- DunnLBNowrangiMAPalmerBWJesteDVSaksERAssessing decisional capacity for clinical research or treatment: a review of instrumentsAm J Psychiatry200616381323133416877642

- SimpsonCDecision-making capacity and informed consent to participate in research by cognitively impaired individualsAppl Nurs Res201023422122621035032

- SturmanEDThe capacity to consent to treatment and research: a review of standardized assessment toolsClin Psychol Rev200525795497415964671

- MoyeJGurreraRJKarelMJEdelsteinBO’ConnellCEmpirical advances in the assessment of the capacity to consent to medical treatment: Clinical implications and research needsClin Psychol Rev20062681054107716137811

- SessumsLLZembrzuskaHJacksonJLDoes this patient have medical decision-making capacity?JAMA2011306442042721791691

- HeinIMDaamsJTroostPLindeboomRLindauerRJ webpage on the InternetAccuracy of assessment instruments for patients’ competence to consent to medical treatment or researchThe Cochrane CollaborationCochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsChichester, UKJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd2015 Available from:http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD011099.pub2Accessed January 3, 2016

- SchmandBGouwenbergBSmitJHJonkerCAssessment of mental competency in community-dwelling elderlyAlzheimer Dis Assoc Disord1999132808710372950

- AppelbaumPSGrissoTMacCAT-CR: MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research2001 Available from: http://shpac.doctorsonly.co.il/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/MacCAT-CR-complete-Hebrew-3-2-13-1.pdfAccessed January 9, 2016

- DeRenzoEGConleyRRLoveRAssessment of capacity to give consent to research participation: state-of-the-art and beyondJ Health Care Law Policy199811668715573430

- BucklesVDPowlishtaKKPalmerJLUnderstanding of informed consent by demented individualsNeurology200361121662166614694026

- JesteDVPalmerBWAppelbaumPSA new brief instrument for assessing decisional capacity for clinical researchArch Gen Psychiatry200764896697417679641

- LeeMThe capacity to consent to research among older adultsEduc Gerontol2010367592603

- ResnickBGruber-BaldiniALPretzer-AboffIReliability and validity of the evaluation to sign consent measureGerontologist2007471697717327542

- HeinIMDaamsJTroostPLindeboomRLindauerRJ webpage on the InternetAccuracy of assessment instruments for patients’ competence to consent to medical treatment or researchThe Cochrane CollaborationCochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsChichester, UKJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd2014 Available from:http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD011099.pub2Accessed January 3, 2016

- KarlawishJHTCasarettDJJamesBDAlzheimer’s disease patients’ and caregivers’ capacity, competency, and reasons to enroll in an early-phase Alzheimer’s disease clinical trialJ Am Geriatr Soc200250122019202412473015

- RubrightJSankarPCasarettDJGurRXieSXKarlawishJA memory and organizational aid improves Alzheimer disease research consent capacity: results of a randomized, controlled trialAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201018121124113220808101

- GrissoTAppelbaumPSHill-FotouhiCThe MacCAT-T: a clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisionsPsychiatr Serv19974811141514199355168

- KimSYCaineEDCurrierGWLeiboviciARyanJMAssessing the competence of persons with Alzheimer’s disease in providing informed consent for participation in researchAm J Psychiatry2001158571271711329391

- GzilFRigaudASLatourFDémence, autonomie et compétenceÉthique publique200810210.4000/ethiquepublique.1453

- SeamanJBTerhorstLGentryAHunsakerAParkerLSLinglerJHPsychometric properties of a decisional capacity screening tool for individuals contemplating participation in Alzheimer’s disease researchJ Alzheimers Dis20154611925765917

- DuronEBoulayMVidalJSCapacity to consent to biomedical research’s evaluation among older cognitively impaired patients. A study to validate the University of California Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent questionnaire in French among older cognitively impaired patientsJ Nutr Health Aging201317438538923538663

- DienerLHugonot-DienerLAlvinoSEuropean Forum for Good Clinical Practice Geriatric Medicine Working PartyGuidance synthesis. Medical research for and with older people in Europe: proposed ethical guidance for good clinical practice: ethical considerationsJ Nutr Health Aging201317762562723933874

- ZayasLHCabassaLJPerezMCCapacity-to-consent in psychiatric research: development and preliminary testing of a screening toolRes Soc Work Pract2005156545556

- KarlawishJHTCasarettDJJamesBDXieSXKimSYHThe ability of persons with Alzheimer disease (AD) to make a decision about taking an AD treatmentNeurology20056491514151915883310

- AppelbaumPSClinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatmentN Engl J Med2007357181834184017978292

- MarsonDCChatterjeeAIngramKKHarrellLEToward a neurologic model of competency: cognitive predictors of capacity to consent in Alzheimer’s disease using three different legal standardsNeurology19964636666728618664

- GurreraRJMoyeJKarelMJAzarARArmestoJCCognitive performance predicts treatment decisional abilities in mild to moderate dementiaNeurology20066691367137216682669

- MoyeJKarelMJAzarARGurreraRJCapacity to consent to treatment: empirical comparison of three instruments in older adults with and without dementiaGerontologist200444216617515075413

- OkonkwoOGriffithHRBelueKMedical decision-making capacity in patients with mild cognitive impairmentNeurology200769151528153517923615

- BouyerCTeulonMToullatGGilRConscience et compréhension du consentement dans la maladie d’Alzheimer. [Awareness and understanding of consent in Alzheimer’s disease]Rev Neurol (Paris)2015171218919525535110

- OkonkwoOCGriffithHRCopelandJNMedical decision-making capacity in mild cognitive impairment: a 3-year longitudinal studyNeurology200871191474148018981368

- StarksteinSEJorgeRMizrahiRRobinsonRGA diagnostic formulation for anosognosia in Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200677671972516549411

- GambinaGBonazziAValbusaVAwareness of cognitive deficits and clinical competence in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: their relevance in clinical practiceNeurol Sci201435338539023959532

- EtchellsEDarzinsPSilberfeldMAssessment of patient capacity to consent to treatmentJ Gen Intern Med199914127349893088

- CrumRMAnthonyJCBassettSSFolsteinMFPopulation-based norms for the mini-mental state examination by age and educational levelJAMA199326918238623918479064

- KimSYHKarlawishJHTCaineEDCurrent state of research on decision-making competence of cognitively impaired elderly personsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200210215116511925276

- PucciEBelardinelliNBorsettiGRodriguezDSignorinoMInformation and competency for consent to pharmacologic clinical trials in Alzheimer disease: an empirical analysis in patients and family caregiversAlzheimer Dis Assoc Disord200115314615411522932

- MarsonDCIngramKKCodyHAHarrellLEAssessing the competency of patients with Alzheimer’s disease under different legal standards. A prototype instrumentArch Neurol199552109499547575221

- PalmerBWDunnLBAppelbaumPSAssessment of capacity to consent to research among older persons with schizophrenia, Alzheimer disease, or diabetes mellitus: comparison of a 3-item questionnaire with a comprehensive standardized capacity instrumentArch Gen Psychiatry200562772673315997013

- TamNTHuyNTThoaLTBParticipants’ understanding of informed consent in clinical trials over three decades: systematic review and meta-analysisBull World Health Organ2015933186H198H25883410

- PorteriCAndreattaCAnglaniLPucciEFrisoniGBUnderstanding information on clinical trials by persons with Alzheimer’s dementia. A pilot studyAging Clin Exp Res200921215816619448388

- FeinbergLFWhitlatchCJAre persons with cognitive impairment able to state consistent choices?Gerontologist200141337438211405435

- NCHS – National Center for Health StatisticsCenters for Disease Control and prevention. FastStats. Therapeutic drug use, United States2015 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf#079Accessed July 27, 2017

- GaleottiFVanacoreNGainottiSAdCare Study GroupHow legislation on decisional capacity can negatively affect the feasibility of clinical trials in patients with dementiaDrugs Aging201229860761422574633

- LivingstonGLeaveyGManelaMMaking decisions for people with dementia who lack capacity: qualitative study of family carers in UKBMJ2010341c418420719843

- KraftSAChoMKConstantineMA comparison of institutional review board professionals’ and patients’ views on consent for research on medical practicesClin Trials Lond Engl2016135555565

- RothLHLidzCWMeiselACompetency to decide about treatment or research: an overview of some empirical dataInt J Law Psychiatry1982512950

- BeanGNishisatoSRectorNAGlancyGThe assessment of competence to make a treatment decision: an empirical approachCan J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr19964128592

- MillerCKO’DonnellDCSearightHRBarbarashRAThe Deaconess Informed Consent Comprehension Test: an assessment tool for clinical research subjectsPharmacotherapy19961658728788888082

- WirshingDAWirshingWCMarderSRLibermanRPMintzJInformed consent: assessment of comprehensionAm J Psychiatry199815511150815119812110

- CarneyMTNeugroschlJMorrisonRSMarinDSiuALThe development and piloting of a capacity assessment toolJ Clin Ethics2001121172311428151

- CasarettDJKarlawishJHTHirschmanKBIdentifying ambulatory cancer patients at risk of impaired capacity to consent to researchJ Pain Symptom Manage200326161562412850644

- AppelbaumPSGrissoTFrankEO’DonnellSKupferDJCompetence of depressed patients for consent to researchAm J Psychiatry199915691380138410484948

- CarpenterWTGoldJMLahtiACDecisional capacity for informed consent in schizophrenia researchArch Gen Psychiatry200057653353810839330

- KovnickJAAppelbaumPSHogeSKLeadbetterRACompetence to consent to research among long-stay inpatients with chronic schizophreniaPsychiatr Serv20035491247125212954941

- JoffeSCookEFClearyPDClarkJWWeeksJCQuality of informed consent: a new measure of understanding among research subjectsJ Natl Cancer Inst200193213914711208884

- SaksERDunnLBMarshallBJNayakGVGolshanSJesteDVThe California Scale of Appreciation: a new instrument to measure the appreciation component of capacity to consent to researchAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200210216617411925277