Abstract

Background

Gerontological research aims at understanding factors that are crucial for mediating “successful aging”. This term denotes the absence of significant disease and disabilities, maintenance of high levels of physical and cognitive function, and preservation of social and productive activities. Preservation of an active lifestyle is considered an effective means through which everyday competence can be attained. In this context, it is crucial to obtain ratings of modern day older adults’ everyday competence by means of appropriate assessments. Here, we introduce the Everyday Competence Questionnaire (ECQ), designed to assess healthy older adults’ everyday competence.

Methods

The ECQ includes 17 items, covering housekeeping, leisure activities, sports, daily routines, manual skills, subjective well-being, and general linguistic usage. The ECQ was administered to a population of 158 healthy subjects aged 60–91 years, who were divided into groups on the basis of their physical activity. These groups were community-dwelling subjects, those living independently and having a sedentary lifestyle, those living independently but characterized by a general lifestyle without any noteworthy physical activity, and those living independently and exercising regularly. Age, gender, and education levels were balanced between the groups.

Results

Using the ECQ, we could identify and distinguish different everyday competence levels between the groups tested: Subjects characterized by an active lifestyle outperformed all other groups. Subjects characterized by a general lifestyle showed higher everyday competence than those with a sedentary lifestyle or subjects who needed care. Furthermore, the ECQ data showed a significant positive correlation between individual physical activity and everyday competence.

Conclusion

The ECQ is a novel tool for the questionnaire-based evaluation of everyday competence among healthy subjects. By including leisure activities, it considers the changed living conditions of modern-day older adults.

Background

In the past few decades we have experienced dramatic changes in the age structure of human populations, especially in industrialized countries. These changes are characterized by an increasing probability of reaching old and very old age.Citation1–Citation3 As a multidimensional reality of life, aging is difficult to define simply.Citation4 The World Health Organization defines aging as a “process of progressive change in the biological, psychological and social structure of individuals”.Citation5 From a biological standpoint, aging is often used synonymously with the term senescence, defined as “a biological process of dysfunctional change by which organisms become less capable of maintaining physiological function and homeostasis with increasing survival”.Citation6 Collectively, these definitions and others reflect the difficulty in defining aging precisely.Citation4 Generally aging is associated with progressive functional loss in perception, cognition, and memory,Citation7 as well as a deterioration of physiological capacities, such as muscle strength, aerobic capacity, and neuromotor coordination.Citation8 Although these changes are highly variable, there is a high probability that older adults suffer from age-related dysfunctions,Citation9 which challenge their independence in everyday life. These increased dysfunctions emphasize the need to understand better the mechanisms of the human aging process on the one hand and to develop strategies to maintain health and functional independence on the other hand. Independence in everyday life is regarded as a crucial feature for “successful aging”, which is defined as the absence of significant disease and disabilities, maintenance of high levels of physical and cognitive function, and preservation of social and productive activities.Citation10,Citation11 Because the loss of independence is inevitably linked to institutionalization, it is regarded as an important socioeconomic factor, especially considering the anticipated demographic changes in industrial civilizations.Citation1–Citation3 There is now agreement that in addition to cardiovascular fitness,Citation12–Citation14 cognitive training,Citation15,Citation16 and healthy nutrition,Citation17,Citation18 an active lifestyle is an important prerequisite for healthy aging, as expressed in the gerontological slogan “use it or lose it”.Citation19,Citation20

Evaluation of everyday competence in old age

Everyday competence refers to “a person’s ability to perform, when necessary, a broad array of activities considered essential for independent living, even though in daily life the individual may not perform these tasks on a regular basis or may only perform a subset of these activities”.Citation21 However, the term “everyday competence” is often interpreted differently. Many investigations refer to instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), eg, handling finances, taking medication, using the phone, shopping, preparing meals, housekeeping, and navigating large distances outdoors.Citation22 Others favor the analysis of leisure activities and the social behavior of older adults.Citation23 Accordingly, the concept of everyday competence is not clearly defined, but it provides a perspective on the life of older adults.Citation24

In the past few decades, a number of studies have investigated the everyday competence of older adults.Citation22,Citation24–Citation32 Some of these studies were not only motivated by the current demographic changes and the general need to understand the mechanisms and consequences of the human aging process, but also by a persisting discrepancy between the results of laboratory-based experiments that showed age-related loss of various functions and the often contradictory and unexpected high everyday competence of subjects observed in their private surroundings.Citation28,Citation33 Performance-based measures use functional tasks in a standardized format.Citation34 A known problem of these tests is that they assess the abilities of subjects under directed optimal conditions rather than their actual habits in everyday life.Citation35 Furthermore, it is known that sometimes it is not a lack of capacity that hinders the performance of older adults, but a deficiency in drive and motivation to initiate certain actions in everyday life conditions.Citation36 Hence, performance-based measures may lead to an incorrect estimation of older adults’ abilities in their private surroundings. Another method to measure functional abilities in older adults and to gather reliable data about everyday behavior is direct observation.Citation37,Citation38 However, direct observation might be biased by the subjects’ knowledge about being monitored. Finally, self and collateral reports allow for a quick assessment of functional abilities in older adults. The main limitation of this method is the often reduced ability of older adults to recall details of their everyday life accurately.Citation39 This limitation can, however, be counterbalanced by an elaborate method of asking for relevant details concerning activities of daily living, thereby possibly improving the quality of the data obtained.

Motivation for developing the ECQ

In the past few years, we have investigated sensorimotor abilities in older adults to study age-related degradation in sensorimotor performance. Further, we developed interventional measures to ameliorate age-related decline in sensorimotor performance and cognition.Citation40–Citation44 During the assessment of sensorimotor performance, we noticed a substantial interindividual variation, indicating that the decline in performance could not be attributed to age alone. Studies on use-dependent plasticity imply that maintaining performance requires regular practice and use.Citation45,Citation46 For example, reduced use because of immobilization of a limb leads to rapid deterioration of cortical representations, which harms associated perception and behavior.Citation47,Citation48 It is, therefore, conceivable that aging reduces everyday life activities to a varying extent, and this contributes to differently impaired sensorimotor abilities. To obtain standardized information about the interdependencies between individual lifestyles and conditions of everyday life promptly on the one hand, and levels of sensorimotor performance on the other, we developed a questionnaire that covers housekeeping, leisure activities, sports, daily routines, manual skills, subjective well-being, and general linguistic usage.

Methods

Subjects

The study is based on data collected from 158 subjects (males 55, females 103). Subjects were recruited from a subject registry, newspaper advertisements, and older adult housing sites. The mean age of the subjects was 72.5 ± 6.1 years (range 60–91 years). All subjects were neurologically healthy. Medication with central nervous effects in the present or reported history was a criterion for exclusion. Subjects with an unclear anamnesis or medical history underwent an examination by a clinical neurologist to ensure neurological health. Basic cognitive abilities were assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).Citation49,Citation50 The inclusion criterion for participation was a score of at least 27 points. This regulation did not apply to Group 4 (nursing care), where subjects reached only 23.7 ± 3.7 points. All the subjects gave their written informed consent before participating in the study. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Ruhr University of Bochum. All the percentages presented in the text or tables are with reference to the complete cohort of 158 subjects. The subgroup arrangements of the cohort are presented in , and lists the education levels of all the subjects.

Table 1 Housing and living conditions. Subjects were divided into four groups representing different lifestyles in terms of independence, social contacts, and physical activity

Table 2 Education of the subjects: overview of the education level, years in professional training, and duration of retirement for all subjects

Differences between subjects (age, education, and gender) in all the groups were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Results showed significant F statistics for the main independent variable (group): F(3, 154) = 35.446; P ≤ 0.000 (R2 = 40.8%). The results of a Chi-square test revealed no confounds between the subjects’ gender and their group membership (χ2(3) = 5.027, P = 0.170). On the other hand, ANOVA revealed significant confounds between the group membership of the subjects and the individual level of education (F(156) = 10.870; P ≤ 0.001) and age (F(154) = 10.627; P ≤ 0.001). Based on these findings, we calculated an analysis of covariance (covariates age and education) that supported a significant main effect for group (F(151) = 21.801; P ≤ 0.001).

Instrument development and data administration

For the construction of the ECQ, we hypothesized that leisure activities might be a valuable indicator of everyday competence. Because life span and health conditions are positively affected by modern medical care, older adults have more time available for hobbies, cultural, and social activities, and sports.Citation24 The questionnaire consisted of 17 items (), where items 1–16 were based on the self-report of the subjects, while item 17 (“fluency of speech”) was based on the ratings of the experimenter. All subjects were asked to respond to the questions in as much detail as possible, thereby giving insight into their habits and living conditions. The experimenter converted the answers into scores using an item-specific scale. The items referred to domains such as leisure activities, sports, subjective well-being, and linguistic abilities. IADL-specific domains such as housekeeping, daily routine, manual skills, and mobility were also considered in the questionnaire. All the items and the corresponding rating scales are listed in .

Table 3 Everyday Competence Questionnaire: the questionnaire consisted of 17 items with one specific question per item (additional information for the investigator is given in parentheses)

Discriminatory power and internal consistency

The internal consistency (estimated by calculation of Cronbach’s coefficient alpha) of all the items was 0.835. Two out of 17 items showed item-total correlations below 0.3 (item 8: 0.285, item 14: 0.243). Because it had very low discriminatory power (0.082), a previously used item (“Do you solve crossword puzzles or brain teasers?”) was omitted from the final version of the questionnaire. A further exclusion of items 8 and 14 did not improve the internal consistency (r = 0.843). Therefore, the final 17-item version of the ECQ was used for all subsequent analyses. Analysis of test-retest reliability revealed high consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.844).

Because the maximal number of points varied between 2 and 5, we normalized the scores of every single item to ensure that all items had the same impact on the total scale of the questionnaire. This was done by dividing the individual number of points obtained by a subject per item by the maximum possible score of the given item. Normalized data revealed similar results in terms of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.843).

Construct validation

A subsample of subjects (n = 83; 37% in Group 1, 51% in Group 2, 4% in Group 3, and 8% in Group 4) took the MMSE.Citation49 Within the narrow distribution of the obtained MMSE scores, which were not normally distributed (Z(KS) = 2.064; P ≤ 0.001), we found a significant correlation between ECQ scores and the scores obtained in the MMSE (Spearman correlation, r = 0.316; P = 0.004).

Another subsample of subjects (n = 40; 25% in Group 1, 70% in Group 2, 5% in Group 3, and 0% in Group 4) took the Nürnberger-Alters-Alltagsaktivitäten-Skala (NAACitation51), which consists of 20 questions designed to collect information about restrictions in everyday activities. High scores in the NAA reflect substantial restrictions in everyday life. We found a significant negative correlation between the NAA scores and the ECQ scores (Pearson correlation, r = −0.320; P = 0.044).

Factor analysis of used items

A factor analysis for all items of the ECQ was conducted using main component analysis with varimax rotation. The Kaiser-Myer-Olkin value was satisfactory, namely, 0.847 (refer to previously published researchCitation52). Bartlett’s test revealed a significant result (χ2(136) = 859.257, P ≤ 0.001). The measure of sampling adequacy for almost all items was distributed between 0.7 and 0.9. As an exception, the value for item 14 was 0.653. Nevertheless, no further item had to be excluded from the analysis (see previous reportsCitation53,Citation54). Using a scree plot analysis, we extracted a four-factor structure from the data. By means of the four factors, 56.1% of the variance within the collected ECQ data could be explained ().

Table 4 Four-factor structure of the Everyday Competence Questionnaire: factor analysis for the questionnaire items revealed a four-factor structure

Results

Analysis of group-specific differences in everyday competence

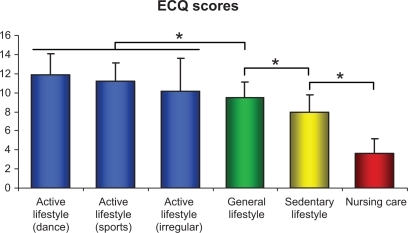

The data obtained from the ECQ were normally distributed (Z(KS) = 0.624, P = 0.831). Homogeneity of variance was examined using Levene’s test (F(154) = 2.512, P = 0.061). In order to analyze possible group-specific differences, we pooled the data of subjects in Group 1 (general lifestyle), 2 (active lifestyle), 3 (sedentary lifestyle), and 4 (nursing care) without differentiating between the subgroups of Group 2. Using an ANOVA (the inter-subject factor was score, the between-subject factor was group) we found a significant main effect in the data, F(3,154) = 35.466, P ≤ 0.001 (R2 = 40.9%). Data revealed top scores (11.17 ± 2.58 points) for the subjects of Group 2 (active lifestyle), 9.48 ± 1.67 points for the subjects of Group 1 (general lifestyle), 7.91 ± 1.89 points for the subjects of Group 3 (sedentary lifestyle), and the lowest scores (3.69 ± 1.47 points) for the subjects of Group 4 (nursing care).

Using post hoc tests (Bonferroni), we found significant differences in ECQ performance of our subjects (see ). Subjects from Group 2 (active lifestyle) outperformed subjects from all other groups (P ≤ 0.001). Subjects from Group 1 (general lifestyle) had significantly higher scores on the ECQ than subjects from Group 3 (sedentary lifestyle, P = 0.014) and Group 4 (nursing care, P ≤ 0.001). Finally, subjects from Group 3 (sedentary lifestyle) had significantly higher scores than subjects from Group 4 (nursing care, P ≤ 0.001).

Figure 1 Everyday Competence Questionnaire scores for all subjects.

Differences in everyday competence in Group 2 (active lifestyle)

According to the individual activities of subjects in Group 2, we divided the subjects into three subgroups, ie, subgroup 2a (regular dancing, n = 30), subgroup 2b (regular workout, n = 22), and subgroup 2c (irregular workout, n = 21). Highest ECQ scores were obtained by the subjects from subgroup 2a (score 11.86 ± 2.20), followed by the subjects from subgroup 2b (score 11.18 ± 1.91) and from subgroup 2c (score 10.19 ± 3.37). After testing the equality of variance with Levene’s test (F(70) = 2,773, P = 0.069),ANOVA revealed a main effect at the 10% significance level (F(2, 70) = 2,818, P = 0.067). The subsequent post hoc analysis (the discriminatory power was adjusted by using the Least Squares Difference test instead of the Bonferroni test) revealed no significant differences between the two regular activity groups (dancing and workout, P = 0.348). There were differences in the performance of subjects with regular and irregular activity; those with regular activity obtained higher scores (P = 0.047). We also found significant differences between subgroup 2a subjects and subgroup 2c subjects, with subgroup 2a subjects obtaining higher scores (P = 0.020).

Discussion

In this study we present a questionnaire which was designed to assess older adults’ competence in activities of everyday life. By means of this 17-item questionnaire, which covers the domains of housekeeping, daily routine, manual skills, sports, leisure activities, subjective well-being, and linguistic abilities, it is possible to obtain ratings on the everyday competence of older adults. By administering the questionnaire to a sample of 158 older adults, characterized by different lifestyles, we observed significant group differences that indicated a strong relationship between individual physical activity level and everyday competence. Furthermore, correlation analyses between results obtained from the ECQ and other tests (MMSE, NAA) provided evidence for the reliability of this new questionnaire.

In industrialized civilizations, in order to experience successful aging, one has to engage not only in activities of daily living and IADL-specific activities that ensure personal maintenance, but also in activities that are related to the external environment and social life. Horgas et al stated that people who engage in more than just basic activities, who participate in the external environment, who turn toward others, and engage in self-enriching activities are considered more successful.Citation55 These authors differentiated between three types of everyday activities: basic activities, ie, those pertaining to personal maintenance in terms of physical survival; instrumental activities, ie, those referring to personal maintenance in terms of cultural survival; and work, leisure, and social activities, ie, those reflecting agentic, communal, and self-enriching activities.Citation55

Leisure activities might be used as a reliable indicator of the changes in the everyday behavior of older adults. Baltes et al stated that during the development of dementia, significant changes occur in everyday behavior. In a longitudinal study based on the Berliner Altersstudie,Citation56 the authors showed that subjects suffering from dementia spend less time on hobbies and consumption of media. Age-related reductions in these activities were significantly lower in age-matched healthy subjects. In that study, the authors discuss the usability of activities of daily living and IADL scales for rating everyday competence, as well as the need to estimate everyday competence in terms of leisure and social activities. Their study supports the view that not only pathological but also age-related changes in the physical and mental health of older adults have a significant impact on activities of daily living and eventually on everyday competence.Citation57 These notions stress the importance of considering leisure time activities for an adequate estimation of everyday competence in older adults.Citation58 Therefore, we incorporated these requirements by including typical leisure activities in the ECQ. Considering the rising life expectancy and the remarkable health conditions even in very old adults, leisure activities might become important indicators of everyday competence among older adults. It is not easy for standard questionnaires to cover the individual activities of modern-day older adults, because the nature of these activities is changing constantly. A few decades ago, it would have been rather uncommon to find older adults taking philosophy classes, taking language vacations in different continents, playing music in an orchestra, or helping to educate trainees in the company they left 20 years earlier. Contemporary assessments of everyday competence have to account for these lifestyle conditions, which are now typically found among older adults.

Our findings support a close positive correlation between physical activity and everyday competence in old age. The ECQ data demonstrate that subjects with an active lifestyle outperform subjects with a general or sedentary lifestyle in terms of everyday competence. These findings are in line with data showing a close association between physical fitness and cognitive performance in healthy older adults.Citation12,Citation14,Citation59,Citation60 In the last few years, there has been a significant increase in general interest in maintaining health and cognitive abilities in old age by means of physical exercise programs.Citation60–Citation66 In fact, there is evidence that maintaining physical fitness reduces the risk of mortality among older adults who are active.Citation67 In the epidemiologic literature, the concept of “compressed morbidity” was introduced, suggesting that active people can live more disability-free years,Citation68 and healthy lifestyles can postpone functional disability.Citation69 Other studies have shown that playing intensive sports is not required for cardiovascular benefits. For example, for sedentary older adults, moderate physical activity seems sufficient for improving health significantly.Citation70,Citation71 These findings might be particularly important for older adults who are not able to participate in demanding sports but can start moderate physical activities, such as walking.Citation72 Dancing might be an attractive alternative to conventional sports because of its high popularity among older adults. Besides physical activity, dancing comprises rhythmic motor coordination, balance and memory, emotions, social interaction, acoustic stimulation, and musical experience.Citation73 Most studies employing dancing as an intervention among older adults focused on the improvement of cardiovascular parameters, muscle strength, and posture and balance,Citation74–Citation82 with a few studies addressing cognitive abilitiesCitation83,Citation84 and the preservation of sensorimotor performance, as well as perceptual abilities.Citation73 Accordingly, dancing seems to be the primary activity for ameliorating everyday competence among healthy older adults.Citation85–Citation90

Conclusion

The ECQ presented in this paper might be a useful tool for obtaining ratings of everyday competence among healthy older adults. A sample of 158 subjects, characterized and predefined by different physical activity levels, could be clearly differentiated by evaluating their individual ECQ scores. Our data support the well documented relationship between physical activity and individual everyday competence in old age. In the future, ECQ scores might be used as markers for individual everyday competence to investigate possible correlations with performance-based measures like physical fitness, sensorimotor abilities, and cognition. Further research is needed to investigate the usefulness of the ECQ in nonhealthy populations of older adults.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Di 334/19-1, HRD; Te 315/4-1, MT), a scholarship from the Research Department of Neuroscience of the Ruhr-University Bochum to TK, and a scholarship to JCK from the Allgemeiner Deutscher Tanzlehrerverband.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DinseHRCortical reorganization in the aging brainProg Brain Res2006157578017167904

- KlenkJRappKBucheleGKeilUWeilandSKIncreasing life expectancy in Germany: Quantitative contributions from changes in age- and disease-specific mortalityEur J Public Health200717658759217403787

- OeppenJVaupelJWDemography. Broken limits to life expectancyScience200229655701029103112004104

- FranklinNCTateCALifestyle and successful aging: An overviewAm J Lifestyle Med200931611

- SteinCMoritzIA Life Course Perspective of Maintaining Independence in Older AgeGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization1999

- CrewsDEHuman Senescence: Evolutionary and Biocultural PerspectivesNew York, NYCambridge University Press2003

- MahnckeHWConnorBBAppelmanJMemory enhancement in healthy older adults using a brain plasticity-based training program: A randomized, controlled studyProc Natl Acad Sci U S A200610333125231252816888038

- SinghASChinAPMJBosscherRJvan MechelenWCross-sectional relationship between physical fitness components and functional performance in older persons living in long-term care facilitiesBMC Geriatr20066416464255

- BuchnerDMLarsonEBWagnerEHKoepsellTDde LateurBJEvidence for a non-linear relationship between leg strength and gait speedAge Ageing19962553863918921145

- RoweJWKahnRLSuccessful agingGerontologist19973744334409279031

- MottaMBennatiEFerlitoLMalaguarneraMMottaLSuccessful aging in centenarians: Myths and realityArch Gerontol Geriatr200540324125115814158

- ColcombeSJKramerAFMcAuleyEEricksonKIScalfPNeurocognitive aging and cardiovascular fitness: Recent findings and future directionsJ Mol Neurosci200424191415314244

- McAuleyEKramerAFColcombeSJCardiovascular fitness and neurocognitive function in older adults: A brief reviewBrain Behav Immun200418321422015116743

- ColcombeSJKramerAFEricksonKICardiovascular fitness, cortical plasticity, and agingProc Natl Acad Sci U S A200410193316332114978288

- BallKBerchDBHelmersKFEffects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: A randomized controlled trialJAMA2002288182271228112425704

- WillisSLTennstedtSLMarsiskeMLong-term effects of cognitive training on everyday functional outcomes in older adultsJAMA2006296232805281417179457

- GalliRLShukitt-HaleBYoudimKAJosephJAFruit polyphenolics and brain aging: Nutritional interventions targeting age-related neuronal and behavioral deficitsAnn N Y Acad Sci200295912813211976192

- JosephJAShukitt-HaleBCasadesusGReversing the deleterious effects of aging on neuronal communication and behavior: Beneficial properties of fruit polyphenolic compoundsAm J Clin Nutr.200581Suppl 1313S316S15640496

- TwomeyLTTaylorJAOld age and physical capacity: Use it or lose itAust J Physiother1984304115120

- CasselCKUse it or lose it: Activity may be the best treatment for agingJAMA2002288182333233512425713

- DiehlMEveryday competence in later life: Current status and future directionsGerontologist19983844224339726129

- WillisSLCognition and everyday competenceAnn Rev Gerontol Geriat11New York, NYSpringer1991

- BaltesMMCarstensenLGutes Leben im Alter: Überlegungen zu einem prozessorientierten Metamodell erfolgreichen AlternsPsychologische Rundschau199647199215

- WahlHWEvery day competence: A construct in search for an identityZ Gerontol Geriatr1998314243249 German.9782581

- CorneliusSWCaspiAEveryday problem solving in adulthood and old agePsychol Aging1987221441533268204

- DiehlMWillisSLSchaieKWEveryday problem solving in older adults: Observational assessment and cognitive correlatesPsychol Aging19951034784918527068

- MarsiskeMWillisSLDimensionality of everyday problem solving in older adultsPsychol Aging19951022692837662186

- ParkDCApplied cognitive aging researchCraikFIMSalthouseTAThe Handbook of Aging and CognitionHillsdale, NYErlbaum1992

- BrennanMHorowitzASuYPDual sensory loss and its impact on everyday competenceGerontologist200545333734615933274

- BrennanMSuYPHorowitzALongitudinal associations between dual sensory impairment and everyday competence among older adultsJ Rehabil Res Dev200643677779217310427

- ChouKLEveryday competence and depressive symptoms: Social support and sense of control as mediators or moderators?Aging Ment Health20059217718315804637

- AllaireJCWillisSLCompetence in everyday activities as a predictor of cognitive risk and mortalityNeuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn200613220722416807199

- WillisSLEveryday problem solvingBirrenJESchaieKWHandbook of the Psychology of Aging4th edNew York, NYAcademic Press1996

- BaumCEdwardsDFCognitive performance in senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: The Kitchen Task AssessmentAm J Occup Ther19934754314368498467

- GlassTAConjugating the “tenses” of function: Discordance among hypothetical, experimental, and enacted function in older adultsGerontologist19983811011129499658

- MooreDJPalmerBWPattersonTLJesteDVA review of performance-based measures of functional living skillsJ Psychiatr Res2007411–29711816360706

- GrangerCVAdvances in functional assessment for medical rehabilitationTop Geriatr Rehabil198615974

- TyronWWBehavioral observationBellackASHersenMBehavioral Assessment: A Practical HandbookNeedham Heights, MAAllyn & Bacon1998

- MagazinerJZimmermanSIGruber-BaldiniALHebelJRFoxKMProxy reporting in five areas of functional status. Comparison with self-reports and observations of performanceAm J Epidemiol199714654184289290502

- KalischTWilimzigCKleibelNTegenthoffMDinseHRAge-related attenuation of dominant hand superiorityPLoS One20061e9017183722

- DinseHRKleibelNKalischTRagertPWilimzigCTegenthoffMTactile coactivation resets age-related decline of human tactile discriminationAnn Neurol2006601889416685697

- DinseHRKalischTRagertPPlegerBSchwenkreisPTegenthoffMImproving human haptic performance in normal and impaired human populations through unattended activation-based learningACM Trans Appl Percept2005227188

- KalischTTegenthoffMDinseHRRepetitive electric stimulation elicits enduring improvement of sensorimotor performance in seniorsNeural Plast2010201069053120414332

- KattenstrothJCKalischTHoltSKTegenthoffMDinseHRBeneficial effects of a six-months dance class on sensorimotor and cognitive performance of elderly individuals1808Chicago, ILSociety for Neuroscience2009 Neuroscience Meeting Planner, online.

- KalischTKattenstrothJCTegenthoffMDinseHRRepetitive electric stimulation as an intervention to enhance sensorimotor functions in long-term chronic stroke patients7693Chicago, ILSociety for Neuroscience2009 Neuroscience Meeting Planner, online.

- SchwenkreisPEl TomSRagertPPlegerBTegenthoffMDinseHRAssessment of sensorimotor cortical representation asymmetries and motor skills in violin playersEur J Neurosci200726113291330218028115

- LiepertJTegenthoffMMalinJPChanges of cortical motor area size during immobilizationElectroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol19959763823868536589

- LissekSWilimzigCStudePImmobilization impairs tactile perception and shrinks somatosensory cortical mapsCurr Biol2009191083784219398335

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res19751231891981202204

- TombaughTNMcIntyreNJThe Mini-Mental State Examination: A comprehensive reviewJ Am Geriatr Soc19924099229351512391

- OswaldWFleischmannUDas Nürnberger Altersinventar (Kurz: NAI)GöttingenVerlag Hogrefe1997

- BrosiusFSPSS 12BonnMtip-Verlag2004

- KaiserHRiceJJiffyLittleMarkIVEduc Psychol Meas.197434111117

- BackhausKErichsonBPlinkeWWeiberRMultivariate AnalysemethodenBerlinSpringer2006

- HorgasALWilmsHUBaltesMMDaily life in very old age: Everyday activities as expression of successful livingGerontologist19983855565589803644

- BaltesMMMaasIWilmsHUBorcheltMAlltagskompetenz im Alter: Theoretische Überlegungen und empirische BefundeMayerKUBaltesPBDie Berliner AltersstudieBerlinAkademie Verlag1996

- WilmsHUBaltesMMKanowskiSDementias and daily competence: Effects beyond ADL and IADLZ Gerontol Geriatr1998314263270 German.9782584

- Tesch-RomerCWilmsHUEvery day competenceZ Gerontol Geriatr1998314241242 German.9782580

- SchäferSHuxholdOLindenbergerUHealthy mind in healthy body? A review of sensorimotor-cognitive interdependencies in old ageEur Rev Aging Phys Act2006324554

- SumicAMichaelYLCarlsonNEHowiesonDBKayeJAPhysical activity and the risk of dementia in oldest oldJ Aging Health200719224225917413134

- LidorRMillerURotsteinAIs research on aging and physical activity really increasing? A bibliometric analysisJ Aging Phys Act19997182195

- KramerAFHahnSCohenNJAgeing, fitness and neurocognitive functionNature1999400674341841910440369

- ColcombeSJEricksonKIScalfPEAerobic exercise training increases brain volume in aging humansJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200661111166117017167157

- DeleyGKervioGvan HoeckeJVergesBGrassiBCasillasJMEffects of a one-year exercise training program in adults over 70 years old: A study with a control groupAging Clin Exp Res200719431031517726362

- HillmanCHEricksonKIKramerAFBe smart, exercise your heart: Exercise effects on brain and cognitionNat Rev Neurosci200891586518094706

- Voelcker-RehageCGoddeBStaudingerUMPhysical and motor fitness are both related to cognition in old ageEur J Neurosci201031116717620092563

- CDCPhysical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon GeneralAtlanta, GAUS Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion1996

- LeveilleSGGuralnikJMFerrucciLLangloisJAAging successfully until death in old age: Opportunities for increasing active life expectancyAm J Epidemiol1999149765466410192313

- VitaAJTerryRBHubertHBFriesJFAging, health risks, and cumulative disabilityN Engl J Med199833815103510419535669

- BaumanAESmithBJHealthy ageing: What role can physical activity play?Med J Aust20001732889010937037

- BlairSNKohlHW3rdBarlowCEPaffenbargerRSJrGibbonsLWMaceraCAChanges in physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy and unhealthy menJAMA199527314109310987707596

- KriskaAPhysical activity and the prevention of Type 2 diabetes mellitus: How much for how long?Sports Med200029314715110739265

- KattenstrothJCKolankowskaIKalischTDinseHRSuperior sensory, motor, and cognitive performance in elderly individuals with multi-year dancing activitiesFront Aging Neurosci20102

- HopkinsDRMurrahBHoegerWWRhodesRCEffect of low-impact aerobic dance on the functional fitness of elderly womenGerontologist19903021891922347499

- EstivillMTherapeutic aspects of aerobic dance participationHealth Care Women Int19951643413507649891

- CrottsDThompsonBNahomMRyanSNewtonRABalance abilities of professional dancers on select balance testsJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther199623112178749745

- ShigematsuRChangMYabushitaNDance-based aerobic exercise may improve indices of falling risk in older womenAge Ageing200231426126612147563

- FedericiABellagambaSRocchiMBDoes dance-based training improve balance in adult and young old subjects? A pilot randomized controlled trialAging Clin Exp Res200517538538916392413

- HuiEChuiBTWooJEffects of dance on physical and psychological well-being in older personsArch Gerontol Geriatr.2009491e45e5018838181

- KreutzGDoes partnered dance promote health? The case of tango ArgentinoJ R Soc Promot Health20081282798418402178

- ZhangJGIshikawa-TakataKYamazakiHMoritaTOhtaTPostural stability and physical performance in social dancersGait Posture200827469770117981468

- SofianidisGHatzitakiVDoukaSGrouiosGEffect of a 10-week traditional dance program on static and dynamic balance control in elderly adultsJ Aging Phys Act200917216718019451666

- VergheseJCognitive and mobility profile of older social dancersJ Am Geriatr Soc20065481241124416913992

- AlpertPTMillerSKWallmannHThe effect of modified jazz dance on balance, cognition, and mood in older adultsJ Am Acad Nurse Pract200921210811519228249

- EarhartGMDance as therapy for individuals with Parkinson diseaseEur J Phys Rehabil Med200945223123819532110

- HackneyMEKantorovichSLevinREarhartGMEffects of tango on functional mobility in Parkinson’s disease: A preliminary studyJ Neurol Phys Ther200731417317918172414

- HackneyMEEarhartGMEffects of dance on gait and balance in Parkinson’s disease: A comparison of partnered and nonpartnered dance movementNeurorehabil Neural Repair200924438439220008820

- HackneyMEEarhartGMEffects of dance on movement control in Parkinson’s disease: A comparison of Argentine tango and American ballroomJ Rehabil Med200941647548119479161

- HokkanenLRantalaLRemesAMHarkonenBViramoPWinbladIDance and movement therapeutic methods in management of dementia: A randomized, controlled studyJ Am Geriatr Soc200856477177218380687

- HackneyMEEarhartGMSocial partnered dance for people with serious and persistent mental illness: A pilot studyJ Nerv Ment Dis20101981767820061874