Abstract

Background

Gastrointestinal cancer is an age-associated disease, and geriatric patients are mostly likely to suffer from postoperative complications. Some studies indicated that comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) could predict postoperative complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients. However, the evidence is mixed.

Objective

This study aimed to conduct a meta-analysis to identify the effectiveness of CGA for predicting postoperative complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients.

Methods

The Joanna Briggs Institute Library, Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, CINAHL Complete and four Chinese databases were searched for studies published up to March 2017. Two reviewers independently screened literature, extracted data and assessed the quality of included studies. RevMan5.3 was used for meta-analysis or only descriptive analysis.

Results

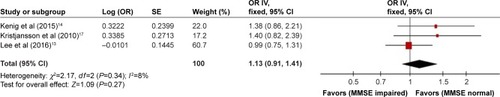

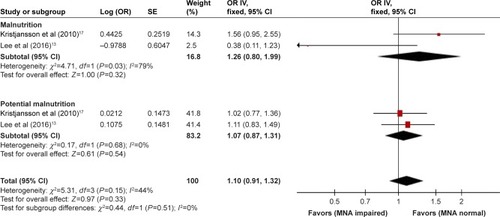

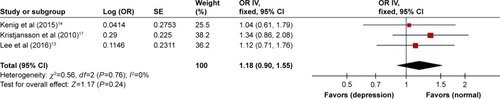

Six studies were included, with 1,037 participants in total. In all, 13 components of CGA were identified, among which comorbidity (Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI] ≥3; odds ratio [OR]=1.31, 95% CI [1.06, 1.63], P=0.01), polypharmacy (≥5 drugs/day; OR=1.30, 95% CI [1.04, 1.61], P=0.02) and activities of daily living (ADL) dependency (OR=1.69, 95% CI [1.20, 2.38], P=0.003) were proven relevant to the prediction of postoperative complications. No conclusive relationship was established between instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) dependency (OR=1.18, 95% CI [0.73, 1.91], P=0.51), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; OR=1.13, 95% CI [0.91, 1.41], P=0.27), potential malnutrition (OR=1.07, 95% CI [0.87, 1.31], P=0.54), malnutrition (OR=1.26, 95% CI [0.80, 1.99], P=0.32), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; OR=1.18, 95% CI [0.90, 1.55], P=0.24) and postoperative complications.

Conclusion

Comorbidity (CCI ≥3), polypharmacy (≥5 drugs/day) and ADL dependency were predictive factors for postoperative complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients; the results of other geriatric instruments were not conclusive, pointing to insufficient studies and requirement of more original investigations.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal cancer is one of the world’s most prevalent malignancies, with a high incidence (stomach and colorectal cancers ranking fifth and third, respectively) and mortality rate (stomach and colorectal cancer ranking third and fourth, respectively).Citation1 In the United States in 2017, an estimated 135,430 individuals newly diagnosed with colorectal cancer and 50,260 deaths from the disease.Citation2 In China alone, there was a sharp increase in the standardized incidence of colorectal cancer (from 12.15/100,000 to 20.27/100,000) and deaths from stomach cancer (from 2.821 million to 3.178 million) from 1990 to 2013.Citation3,Citation4 Considering challenges arising with aging societies, study showed that nearly 60% of newly diagnosed colorectal cancer occurs in people older than 65 years.Citation2

Age probably is an independent risk factor for complications, but age alone does not exclude surgery as a treatment option.Citation5 With the advances in surgical and anesthetic techniques, the extended life expectancy of the elderly, patients aged ≥65 years with cancer tend to surgical treatment and the surgical resection rate is high even in advanced age.Citation6 However, geriatric patients are most likely to be in poor health state due to combinations of physiological age-associated decline, multiple illnesses, psychological alterations and geriatric syndromes. When surgery is performed, these vulnerabilities may lead to compromised postoperative outcomes, including increased incidence of complications, extended hospitalization, progressive functional decline and death.Citation7,Citation8 Therefore, thorough assessment is critical for geriatric patients being considered for surgery to recognize risk factors and take individualized care.Citation7

Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) is a multidimensional evaluation of general health condition based on validated scales and tests producing an inventory of health problems designed by geriatricians.Citation9 CGA is different from those traditional evaluation treatments as it is a multidimensional, interdisciplinary and comprehensive diagnostic process. It provides systematic structured assessment of patient’s overall health status including physical function, nutrition, mental or psychological status, functional status (FS), social support and geriatric syndromes. CGA is helpful to identify deficits that are not routinely captured in a standard history and physical examination, determine risk stratification, make surgical decisions and guide targeted geriatric interventions in response to CGA impairments and thus optimizes preoperative health state and improves postoperative outcomes.Citation10–Citation12

Recently, some studies indicated that components of CGA could predict postoperative complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients, but empirical evidence is mixed.Citation13,Citation14 Therefore, this study aimed to conduct a meta-analysis to identify the effectiveness of CGA for predicting postoperative complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients, in order to provide scientifically substantiated suggestions for perioperative clinical care.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies both in English and Chinese with the following criteria were included: 1) types of participants: patients aged ≥65 years undergoing elective surgery for gastrointestinal cancer; 2) types of studies: observational studies including case–control and cohort studies reporting factors (single factor excluded) that included CGA for predicting postoperative complications and 3) types of outcome measures: postoperative complications occurring within 30 or 90 days after surgery.

Studies were excluded if valid data information could not be extracted or only the abstract (full text unavailable) was available.

Search strategy

The following databases were used to search: Cochrane Library, Joanna Briggs Institute Library, PubMed, Embase (via Ovid), Web of Science, CINAHL Complete, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), Wanfang and VIP database. The search was limited to March 2017. We developed detailed search strategies (Supplementary material) based on the MeSH and text word strategy. The search terms were: (“comprehensive geriatric assessment” OR “CGA”) AND (“stomach” OR “gastric” OR “colon” OR “rectal” OR “colorectal” OR “gastrointestinal”) AND (“cancer” OR “tumor” OR “neoplasms” OR “carcinoma”). Two researchers, Xue and Wu, independently abstracted data from the search methods mentioned earlier including four steps: 1) retrieved the Cochrane Library and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Library for related systematic reviews or meta-analyses; 2) the original research of PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, CNKI, CBM, Wanfang and other Chinese and English databases were searched, and the obtained literature titles, abstracts, keywords and MeSH words were analyzed to further determine the keywords of literature retrieval; 3) used all relevant keywords and MeSH words for further search, and if the abstract met the inclusion criteria, read the full text and 4) further retrieved the references of the related research.

Data extraction

Full article review was conducted for all included studies. Two researchers extracted the study data including first author’s last name, country, design of study, duration of study, cancer type, sample size, mean age, outcome and main conclusion ().

Table 1 Characteristics of the included studies

Quality assessment

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used for quality assessment.Citation15 The scale evaluates each study on eight items grouped into three categories including the study population selection, comparability and outcome. A study can be awarded one star for each item within the study population selection and outcome categories and two stars for comparability. One star refers to a score of 1, and studies with a total score of ≥7 were considered as high-quality studies. Both reviewers independently assessed the quality of the included studies. If there was any divergence, the third reviewer (Cheng) was sought to reach a consensus.

Statistical analysis

First, the existence of clinical and methodological heterogeneity between the studies was judged. Subgroup analysis was conducted where there was clinical heterogeneity and methodological heterogeneity on the basis of the factors leading to heterogeneity or only descriptive analysis. In the absence of clinical heterogeneity and methodological heterogeneity and on meeting the quality of the criteria, meta-analysis was performed using RevMan 5.3 software. The statistical heterogeneity between studies was determined based on the chi-square test. The fixed-effects model was used when heterogeneity was not significant (P≥0.1, I2<50%), otherwise the random-effects model was used.

Results

Study selection

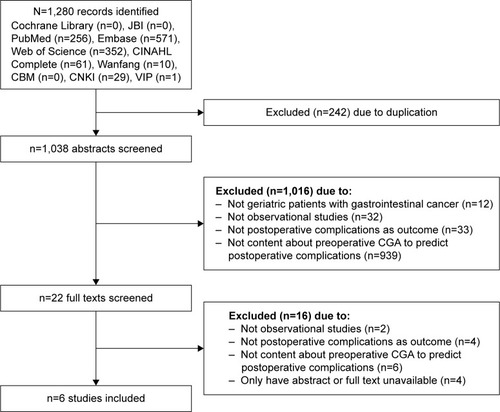

As shown in , the searches identified 1,280 potentially relevant studies. In all, 242 articles were excluded due to duplication. After screening the titles and abstracts, we excluded 1,016 studies. The 22 full-text studies were reviewed, and 16 articles were excluded because there were no geriatric patients with gastrointestinal cancer as subjects, they were not observational studies and they did not report postoperative complications as outcome or preoperative CGA for predicting postoperative complications. A total of four studies were excluded due to having an abstract only or full text unavailable. Two reports on the same study were included in the meta-analysis (but the reported factors focused on were different): one report determined frailty based on CGA results and explored the relationship between frailty and postoperative complicationsCitation16 and another report analyzed the association between components of CGA and postoperative complications.Citation17 Finally, six studies with 1,037 participants were included in the final analysis.

Characteristics of studies

The characteristics of the included six studies are presented in . They were published between 2010 and 2016 and conducted in five countries, including Poland, Singapore, USA, Korea and Norway. The sample size ranged from 75 to 279 participants, and the mean age varied from 64 to 81.5 years. The incidence of postoperative complications was from 24% to 76.3%. In all, 13 components of CGA were assessed in the six studies (). Six components of CGA including comorbidity, polypharmacy, FS, cognition, depression and nutritional status were evaluated in four or more than four studies. Frailty was assessed in two studies, and other six components including falls, pain, physical activity, fatigue, social support and delirium were assessed only in one study. Different assessment tools were used for nutrition (four methods), comorbidity, FS, cognition (three methods) and frailty (two methods). Depression, falls, pain, physical activity, fatigue, social support and delirium were evaluated by the same measure.

Table 2 Elements of CGA and assessment tools

Methodological quality

Results of NOS assessment are shown in , which identified four cohort studiesCitation14,Citation16–Citation18 with a high quality. Description of the ascertainment of exposure was missing in four studies.Citation14,Citation16,Citation18,Citation19 Two studiesCitation13,Citation19 failed to adjust the risk factors, and the assessment of outcome was insufficient in three studies.Citation13,Citation18,Citation19

Table 3 Quality assessment

30-day postoperative any complications

Postoperative any complications means any event requiring treatment measures that were not routinely applied in the postoperative period and were assessed in three of the six studies.Citation14,Citation16,Citation17 Elements of CGA including Timed Up and Go Test (TUGT), Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale (MOS-SSS), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) dependency and depression were predictive factors of 30-day postoperative any complications.Citation14,Citation17 Additionally, frailty was significant with 30-day postoperative any complications.Citation16

30-day postoperative major complications

Postoperative major complications referred to complications of grade 2 or higher according to the Clavien–Dindo classification, either life threatening or requiring significant deviation from standard treatment.Citation18,Citation20 The 30-day postoperative major complications were assessed in five of the six studies, and all the five studies analyzed the association between elements of preoperative CGA and 30-day postoperative major complications.Citation11,Citation12,Citation14–Citation16

Comorbidity

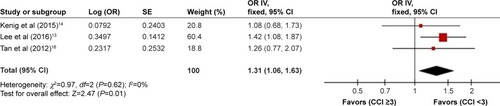

Comorbidity was assessed in all six studiesCitation13,Citation14,Citation16–Citation19 using three different tools, including Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) and Satario’s Index. Four studies reported the relationship between comorbidity and 30-day postoperative major complications.Citation13,Citation14,Citation17,Citation18 One study showed that severe comorbidity was an independent predictor of major complications.Citation17 In this study, comorbidities were classified according to CIRS scores, and severe comorbidities were defined as three grade 3 comorbidities or any grade 4 comorbidity. Two studies analyzed the association between a score of ≥3 for CCI and 30-day postoperative major complications.Citation13,Citation14 One prospective study analyzed the predictive value of a score of >5 for CCI for the development of 30-day postoperative major complications.Citation18 There was no heterogeneity among the three studies (P=0.62, I2=0%). In the fixed-effects model, CCI ≥3 was identified as the predictive factor of 30-day postoperative major complications (odds ratio [OR]=1.31, 95% CI [1.06, 1.63], P=0.01; ).

Polypharmacy

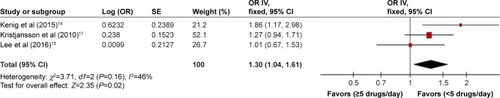

Polypharmacy was assessed in five studies.Citation13,Citation14,Citation16–Citation18 Three studies identified the association between polypharmacy and 30-day postoperative major complications.Citation13,Citation14,Citation17 Of these studies, one defined polypharmacy as 4 or 5 drugs/day and showed the association between >4 drugs/day, >5 drugs/day and 30-day postoperative major complications.Citation14 One study defined it as more than or equal to five daily medications.Citation17 Lee et alCitation13 defined polypharmacy as the regular use of eight or more drugs. There was no heterogeneity among the three studies (P=0.16, I2=46%). In the fixed-effects model, ≥5 drugs/day was identified as the predictive factor of 30-day postoperative major complications (OR=1.30, 95% CI [1.04, 1.61], P=0.02; ).

FS

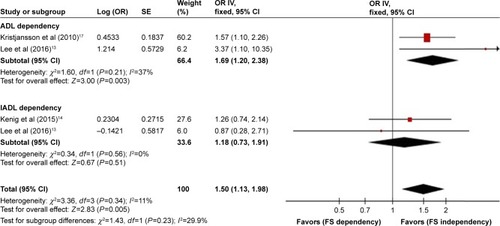

FS was assessed in four of the six studies,Citation13,Citation14,Citation16,Citation17 using tools that included ADL, IADL and Barthel Index (BI). Three studies analyzed the association between FS and 30-day postoperative major complications.Citation13,Citation14,Citation17 One study explained the relationship between BI and postoperative complications and revealed that BI was not a predictive factor of 30-day postoperative major complications.Citation17 Two studies analyzed the relationship between ADL dependency,Citation13,Citation17 IADL dependencyCitation13,Citation14 and 30-day postoperative major complications. Subgroup analysis was conducted based on the evaluation tools; there was no heterogeneity among the three studies (P=0.34, I2=11%). In the fixed-effects model, ADL dependency was identified as a predictive factor of 30-day postoperative major complications (OR=1.69, 95% CI [1.20, 2.38], P=0.003); the prediction of IADL dependency was inconclusive (OR=1.18, 95% CI [0.73, 1.91], P=0.51; ).

Cognition

Cognition was assessed in four of the five studies.Citation13,Citation14,Citation16,Citation17 Three studiesCitation13,Citation16,Citation17 used Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) to evaluate cognition, and oneCitation14 study used three measures, including the MMSE, Blessed Orientation Memory Concentration (BOMC) Test and Clock Drawing Test (CDT). Three studiesCitation13,Citation14,Citation17 analyzed the association between MMSE cognitive impairment and 30-day postoperative major complications, and there was no heterogeneity among the three studies (P=0.34, I2=8%). In the fixed-effects model, the prediction of MMSE cognitive impairment for 30-day postoperative major complications was inconclusive (OR=1.13, 95% CI [0.91, 1.41], P=0.27; ).

Nutrition

Nutrition was assessed in all five studies;Citation13,Citation14,Citation16–Citation18 the methods included Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), the level of serum albumin, weight loss and body mass index (BMI). One study analyzed the relationship between MNA malnutrition and potential malnutrition and 30-day postoperative major complications.Citation14 Two studies analyzed the association between MNA malnutrition, potential malnutrition and 30-day postoperative major complications.Citation13,Citation17 Subgroup analysis was conducted based on the score of MNA; there were no heterogeneity among the two studies (P=0.15, I2=44%). In the fixed-effects model, the prediction of MNA malnutrition (OR=1.26, 95% CI [0.80, 1.99], P=0.32), MNA potential malnutrition (OR=1.07, 95% CI [0.87, 1.31], P=0.54) and 30-day postoperative major complications was inconclusive ().

Depression

Depression was assessed in four of the five studies, and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was used to evaluate it.Citation13,Citation14,Citation16,Citation17 Three studies analyzed the association between GDS depression and 30-day postoperative major complications.Citation13,Citation14,Citation17 There were no heterogeneity among the three studies (P=0.76, I2=0%). In the fixed-effects model, the prediction of GDS depression for 30-day postoperative major complications was inconclusive (OR=1.18, 95% CI [0.90, 1.55], P=0.24; ).

Frailty

Frailty was assessed in two of the five studies.Citation16,Citation18 One study categorized patients into three groups including fit, intermediate and frail based on the preoperative CGA assessment, revealing that frailty was significantly associated with 30-day postoperative major complications.Citation16 Tan et alCitation18 used Fried criteria to evaluate frailty and showed that patients who were positive for the frailty syndrome have a significant four times higher risk of developing 30-day postoperative major complications.

90-day postoperative major complications

Ninety-day postoperative major complications were assessed in one study, and it demonstrated that polypharmacy, pain scale score >0 and ≥10% weight loss in the past half year were independently related to 90-day postoperative major complications.Citation19

Discussion

Predictive value of components of CGA for postoperative complications

Comorbidity

Comorbidities referred to underlying diseases (physical or mental) in patients, other than the disease under treatment.Citation21 CCI was used to evaluate the severity of comorbidities, and this study showed that CCI ≥3 was a predictor of 30-day postoperative major complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients. A study by Tan et alCitation23 proved that CCI ≥5 was an independent predictive factor of postoperative morbidity for octogenarians undergoing colorectal cancer surgery. Another study involving 204 patients with a median age of 84 years who had surgery for colorectal cancer showed that CCI >3 can predict worse perioperative complications independently.Citation22 Age-associated organ reserve decline, compounded by chronic diseases, has led to high incidence of postoperative complications in the elderly patients.Citation24 The more the comorbidities and their seriousness, the higher the incidence of postoperative complications.Citation24

Polypharmacy

Polypharmacy broadly means use of a large number of medications and potentially unsuitable medications increasing the risk for adverse drug events, medication underuse and duplication.Citation25 It was reported that geriatric patients are great consumers of medications (3.9 drugs/day for ages 65–80 years, 4.4 drugs/day for ages >80 years) and the most common prescription drugs are cardiovascular medications (65%), followed by those acting on the central nervous system.Citation26 This study found that polypharmacy (≥5 drugs/day) could predict postoperative major complications, which was consistent with the result of the study of Pujara et al.Citation19 Elderly patients are more sensitive to the effects of drugs due to age-related changes in pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, and the greater the number of drugs, the more the side effects caused by them.Citation26 Some medications such as anticholinergic drugs, meperidine and benzodiazepines would increase the risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction, a common postoperative major complication.Citation27

FS

FS focused on the patient’s abilities to perform ADL.Citation28 It can be assessed in numerous ways; ADL and IADL were used most frequently, and it was reported that the prevalence of ADL and IADL dependency for geriatric patients ranged from 7.5% to 51.4% and from 10.8% to 72.9%, respectively.Citation13,Citation29,Citation30 This study indicated that ADL dependency could predict 30-day postoperative major complications and the prediction of IADL dependency was inconclusive. Lee et alCitation13 involved a multivariable analysis of the CGA domains and revealed that low ADL was significantly and independently associated with a risk of developing postoperative major complications. A recent study by Leavitt et alCitation31 showed that ADL could predict complications following percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Patients with ADL deficiency may not have enough physiological reserve to endure and rehabilitate from a major surgery successfully.Citation31 Kothari et alCitation32 demonstrated in a prospective study enrolling patients ≥70 years old scheduled for thoracic surgery that dependency with IADL “shopping” was a predictive factor for 30-day major complications. It was suggested that more prospective investigations of a minimal data set containing these parameters may be conducted to explore the prediction of IADL dependency for postoperative major complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients.

Cognition

Cognitive impairment is common in elderly patients, and studies showed that the prevalence ranged from 7% to 56%.Citation17,Citation33 In this study, it was found that the prediction of MMSE cognitive impairment for 30-day postoperative major complications was inconclusive, which was similar to the research by Lee et al.Citation13 However, Maekawa et alCitation34 recently demonstrated in a retrospective study of 517 patients aged 75 years or older with gastrointestinal cancer surgery that MMSE was an independent factor related to the incidence of postoperative delirium after adjusting traditional risk factors. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed in the research of Zhang et alCitation24 and showed that cognitive function evaluated by Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) was an independent influencing factor for postoperative complications. Explanations may be that patients with impaired cognition were less likely to engage in postoperative aggressive pulmonary toilet and ambulation, causing a high risk of developing postoperative complications such as pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, stroke and cerebrovascular accident with neurologic deficit.Citation35 Different results might exist because of different diagnostic accuracies of cognitive evaluation tools, and investigations using high sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy of instruments need to be carried out.

Nutrition

Nutritional status is frequently impaired in geriatric patients with cancer due to reduced appetite, dental diseases and tumor-induced changes in metabolism, especially those with gastrointestinal cancer, with the reported high prevalence of up to 45.6%.Citation36,Citation37 This study did not show that malnutrition or potential malnutrition based on MNA could predict 30-day postoperative major complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients. However, one prospective study found that malnourished patients assessed by Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) were at risk for increased postoperative morbidity undergoing elective resection of colorectal cancer.Citation38 A research from Mohri et alCitation39 using Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) to evaluate nutrition revealed that preoperative PNI was a useful predictor for postoperative complications in patients with colorectal cancer. A number of assessment tools exist to identify malnutrition in patients with colorectal cancer, but different tools have different diagnostic accuracies and lack a standardized method.Citation40,Citation41 Therefore, it was recommended that a high-accuracy diagnostic test of nutritional tools based on evidence should be used to further determine the predictive value of nutritional status for postoperative complications.

Depression

Senility alone is a high risk factor for depression, and the preoperative psychological burden that patients likely suffer (eg, fear and concerns about the disease, outcome of the operation and postoperative complications) may complicate the situation; it was well known that the prevalence of depression for elderly oncological patients ranged from 11% to 44.5%.Citation17,Citation30,Citation42 This study found that the prediction of GDS depression for 30-day postoperative major complications was inconclusive, similar to the research from Lee et al.Citation13 However, a retrospective study enrolling patients >75 years of age with colorectal cancer surgery revealed that GDS was an independent factor of postoperative delirium.Citation6 Kothari et alCitation32 proposed that answering “yes” to GDS question 2 “Have you dropped many of your activities and interests?” was able to predict the incidence of major complications for patients with thoracic cancer. Findings from studies provided mixed results, and more prospective investigations of a minimal data set containing these parameters may be required to explore the prediction of depression for postoperative major complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients.

Frailty

Two of the included studies showed that frailty was a predictive factor of postoperative complications in elderly gastrointestinal cancer patients. Recently, a research from Petrakis et alCitation43 used CGA to measure preoperative frailty and found that severe complications were more likely to happen in the frailty group of patients with colorectal cancer. Kristjansson et alCitation44 demonstrated that surgeon’s clinical judgment of frailty based on CGA predicted severe complications after elective colorectal surgery. These studies confirmed the potential benefits of evaluating frailty; it was indispensable to identify frailty patients prior to surgery, and so proper risk/benefit assessment can be performed.Citation45,Citation46

Preoperative CGA for geriatric patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing surgery

This meta-analysis set out with the aim of identifying the effectiveness of CGA for predicting postoperative complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients and showed that comorbidity (CCI≥3), polypharmacy (≥5 drugs/day) and ADL dependency were valid predictive factors; the results of other geriatric instruments were not conclusive. It implies that comorbidity, polypharmacy and FS should be evaluated routinely for geriatric patients undergoing surgery. ADL was suggested to assess FS, evaluating home safety and fall risks and ordering physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) to address impairments. Reviewing and documenting the complete medication lists to monitor for polypharmacy, discontinuing or substituting medications potentially unsuitable or reducing doses thus optimized preoperative status of geriatric patients.Citation11,Citation12,Citation47

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) and the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) published guidelines focusing on optimal preoperative assessment of the geriatric surgical patients, including multiple components of CGA such as cognition (Mini-Cog), depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-2), FS (ADL and IADL) and nutrition.Citation48 An expert advice lately developed by the Chinese Medical Association of Geriatrics and the Department of Geriatrics of People’s Liberation Army General Hospital recommended to use MMSE, ADL and GDS to assess elderly patients undergoing surgery.Citation48 A panel from the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) proposed that domains including FS, cognition, mental health status, nutrition and geriatric syndromes should be evaluated using CGA and tools be available for implementation of CGA, but they could not endorse one instrument over another.Citation12 More definitive studies are required to investigate the predictive value of instruments of CGA for predicting postoperative complications and standardizing assessment tools.

CGA is a multidimensional evaluation that involves patient’s physical, mental and social well-being.Citation10 Preoperative CGA could be helpful to identify existing or potential health problems, determine risk stratification, make decisions and implement goal-directed geriatric interventions in response to CGA deficits, thus optimizing preoperative status of elderly surgical patients and promoting perioperative care.Citation11,Citation12,Citation47 Although CGA has extensively been studied and proposed as part of routine preoperative care among geriatric surgical oncology population, utilization of preoperative CGA remains limited.Citation11,Citation49 A recent survey showed only 6.4% of surgeons use CGA in their routine practice and only a minority of them screen for frailty.Citation5

One reason may be that some screening tools of CGA are lengthy, making them impractical in a high-volume surgical practice.Citation32 What is more, it was likely because geriatric management interventions have not been robustly studied in cancer population.Citation11 Further studies may be required to develop and validate novel, short assessment tools for predicting postoperative complications and execute clinical trials investigating the impact of geriatric management interventions on outcomes in geriatric patients following cancer surgery.

Limitations

There are some limitations of this review. Fewer studies were included into this meta-analysis. Only four of the six studies were adjusted for possible risk factors such as age, sex and operative time; the adjustment factors in each study may be different, and other studies did not mention the adjustment. In addition, because different evaluation tools for each element of CGA were used in different studies, so there may exist heterogeneity among the studies. Subgroup analysis was conducted for some elements of CGA or only descriptive analysis. It was recommended that future studies should apply evidence-based assessment tools with a high diagnostic accuracy to further explore the predictive value of CGA for postoperative complications in elderly patients with gastrointestinal cancer surgery.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis showed that comorbidity (CCI ≥3), polypharmacy (≥5 drugs/day) and ADL dependency were predictive factors for postoperative complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients; the results of other geriatric instruments were not conclusive, pointing to insufficient studies and requirement of original investigations.

Supplementary materials

Search strategy used

PubMed

((Stomach neoplasms OR colorectal neoplasms OR rectal neoplasms [MESH Terms]) OR (gastrointestinal neoplasms [Text Word])) AND (Comprehensive geriatric assessment [Text Word] OR CGA [Text Word] OR geriatric assessment [Text Word]).

Embase

(Stomach OR gastric OR colon OR rectal OR colorectal OR gastrointestinal).mp. AND (Neoplasms OR cancer OR carcinoma OR tumor).mp. AND (comprehensive geriatric assessment OR CGA OR geriatric assessment).mp.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (grant number16411951200).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- International Agency for Research, WHOGOLBOCAN2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012 [EB/OL]2017 Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx

- SiegelRLMillerKDJemalACancer statisticsCA Cancer J Clin20176773028055103

- FengYJWangNFangLWBurden of disease of colorectal cancer in the Chinese population, in 1990 and 2013Chin J Epidemiol2016376768772

- WangBHWangNFengYJDisease burden of stomach cancer in the Chinese population, in 1990 and 2013Chin J Epidemiol2016376763767

- GhignoneFvan LeeuwenBLMontroniIThe assessment and management of older cancer patients: a SIOG surgical task force survey on surgeons’ attitudesEur J Surg Oncol201542229730226718329

- MokutaniYMizushimaTYamasakiMRakugiHDokiYMoriMPrediction of postoperative complications following elective surgery in elderly patients with colorectal cancer using the comprehensive geriatric assessmentDig Surg201633647027250985

- KnittelJGWildesTSPreoperative assessment of geriatric patientsAnesthesiol Clin201634117118326927746

- GriffithsRBeechFBrownAPerioperative care of the elderly 2014: association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and IrelandAnaesthesia201469suppl 1S81S98

- CailletPLaurentMBastujigarinSOptimal management of elderly cancer patients: usefulness of the Comprehensive Geriatric AssessmentClin Interv Aging201491645166025302022

- SongYTGeriatric Comprehensive Assessment1st edBeijingPeking Union Medical College2012

- MagnusonAAlloreHCohenHJGeriatric assessment with management in cancer care: current evidence and potential mechanisms for future researchJ Geriatr Oncol20167424227197915

- WildiersHHeerenPPutsMInternational Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancerJ Clin Oncol201432242595260325071125

- LeeYHOhHKKimDWUse of a comprehensive geriatric assessment to predict short-term postoperative outcome in elderly patients with colorectal cancerAnn Coloproctol201632516116927847786

- KenigJOlszewskaUZychiewiczBBarczynskiMMituś-KenigMCumulative deficit model of geriatric assessment to predict the postoperative outcomes of older patients with solid abdominal cancerJ Geriatr Oncol2015637037926144556

- StangACritical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysesEur J Epidemiol201025960360520652370

- KristjanssonSRNesbakkenAJordhøyMSComprehensive geriatric assessment can predict complications in elderly patients after elective surgery for colorectal cancer: a prospective observational cohort studyCrit Rev Oncol Hematol201076320821720005123

- KristjanssonSRJordhøyMSNesbakkenAWhich elements of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) predict post-operative complications and early mortality after colorectal cancer surgery?J Geriatr Oncol2010125765

- TanKYKawamuraYJTokomitsuATangTAssessment for frailty is useful for predicting morbidity in elderly patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection whose comorbidities are already optimizedAm J Surg2012204213914322178483

- PujaraDMansfieldPAjaniJComprehensive geriatric assessment in patients with gastric and gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma undergoing gastrectomyJ Surg Oncol2015112888388726482869

- ClavienPABarkunJde OliveiraMLThe Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experienceAnn Surg2009250218719619638912

- TairaNSawakiMTakahashiMShimozumaKOhashiYComprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly breast cancer patientsBreast Cancer201017318318919756923

- TanKKKohFHTanYYLiuJZSimRLong-term outcome following surgery for colorectal cancers in octogenarians: a single institution’s experience of 204 patientsJ Gastrointest Surg20121651029103622258874

- TanKYKawamuraYMizokamiKColorectal surgery in octogenarian patients-outcomes and predictors of morbidityInt J Colorectal Dis200924218518919050901

- ZhangXWangBHChenSPPredictive efficacy of comprehensive geriatric assessment for postoperative adverse events in elderly patients during perioperative periodChin Nurs Res2017311113051310

- MaggioreRJGrossCPHurriaAPolypharmacy in older adults with cancerOncologist201015550752220418534

- BettelliGPreoperative evaluation in geriatric surgery: comorbidity, functional status and pharmacological historyMinerva Anestesiol201177663764621617627

- InouyeSKRobinsonTBlaumCAmerican Geriatrics Society abstracted clinical practice guideline for postoperative delirium in older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc201563114215025495432

- TsiourisAHorstHMPaoneGHodariAEichenhornMRubinfeldIPreoperative risk stratification for thoracic surgery using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data set: functional status predicts morbidity and mortalityJ Surg Res201217711622484381

- KenisCDecosterLVanPKPerformance of two geriatric screening tools in older patients with cancerJ Clin Oncol2014321192624276775

- HoppeSRainfrayMFonckMFunctional decline in older patients with cancer receiving first-line chemotherapyJ Clin Oncol201331313877388224062399

- LeavittDAMotamediniaPMoranSCan activities of daily living predict for complications following percutaneous nephrolithotomy?J Urol201519561805180926721225

- KothariAPhillipsSBretlTBlockKWeigelTComponents of geriatric assessments predict thoracic surgery outcomesJ Surg Res2011166151320828735

- SmithNAYeowYYUse of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test to investigate the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in the elderly elective surgical populationAnaesth Intensive Care201644558158627608340

- MaekawaYSugimotoKYamasakiMComprehensive Geriatric Assessment is a useful predictive tool for postoperative delirium after gastrointestinal surgery in old-old adultsGeriatr Gerontol Int20161691036104226311242

- GajdosCKileDHawnMTFinlaysonEHendersonWGRobinsonTNThe significance of preoperative impaired sensorium on surgical outcomes in nonemergent general surgical operationsJAMA Surg201415013036

- WuBYinTTCaoWValidation of the Chinese version of the Subjective Global Assessment scale of nutritional status in a sample of patients with gastrointestinal cancerInt J Nurs Stud201047332333119700157

- KimSBrooksAKGrobanLPreoperative assessment of the older surgical patient: honing in on geriatric syndromesClin Interv Aging201510132725565783

- LohsiriwatVThe influence of preoperative nutritional status on the outcomes of an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programme for colorectal cancer surgeryTech Coloproctol201418111075108025216721

- MohriYInoueYTanakaKPrognostic nutritional index predicts postoperative outcome in colorectal cancerWorld J Surg201337112688269223884382

- HåkonsenSJPedersenPUBath-HextallFKirkpatrickPDiagnostic test accuracy of nutritional tools used to identify undernutrition in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic reviewJBI Database System Rev Implement Rep2015134141187

- LiuXXuPQiuHPreoperative nutritional deficiency is a useful predictor of postoperative outcome in patients undergoing curative resection for gastric cancerTransl Oncol20169648248827788388

- LiuYPZhangJResearch progress on depression of colorectal cancer patients and its influencing factorsChin Nurs Res2014287774777

- PetrakisIEAndreouAGVenianakiMVP460: outcome following colorectal surgery in elderly patients: our experience using the preoperative comprehensive geriatric assessmentEur Geriatr Med20145suppl 1S227S228

- KristjanssonSRJordhoyMSNesbakkenAAre surgeons able to identify frailty status pre-operatively in older patients with colorectal cancer?Eur Geriatr Med20134suppl 1S95

- IsharwalSJohanningJMDwyerJGSchimidKKLaGrangeCAPreoperative frailty predicts postoperative complications and mortality in urology patientsWorld J Urol2017351212627172940

- RevenigLMCanterDJMasterVAA prospective study examining the association between preoperative frailty and postoperative complications in patients undergoing minimally invasive surgeryJ Endourol201428447648024308497

- ChowWBRosenthalRAMerkowRPOptimal preoperative assessment of the geriatric surgical patient: a best practices guideline from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics SocietyJ Am Coll Surg2012215445346622917646

- Chinese Medical Association of Geriatrics, Department of Geriatrics of People’s Liberation Army General HospitalThe expert advice of preoperative assessment for geriatric patientsChin J Geriatr2015341112731280

- FengMAMcMillanDTCrowellKMussHNielsenMESmithABGeriatric assessment in surgical oncology: a systematic reviewJ Surg Res2015193126527225091339