Abstract

Purpose

Frailty is an important consideration in the management of lower urinary tract symptoms and erectile dysfunction in older men; frailty increases vulnerability to treatment-related adverse outcomes, but its burden is not known. The authors aimed to examine the burden of frailty and associated geriatric conditions in community-dwelling older men.

Patients and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted with 492 community-dwelling older men (mean age, 74.2 years; standard deviation, 5.6 years). All the participants were administered the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) (range: 0–35) and a five-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) (range: 5–25). Frailty phenotype was assessed based on exhaustion, inactivity, slowness, weakness, and weight loss. Prevalence of frailty phenotype and geriatric conditions were assessed by the IPSS severity category (mild, 0–7; moderate, 8–19; severe, 20–35 points) and the first IIEF-5 question, which assesses the confidence in erectile function (low, 1–2; moderate, 3; high, 4–5 points).

Results

Older men with severe urologic symptoms had a high prevalence of frailty. According to the IPSS questionnaire, the prevalence of frailty was 7.3% (21/288) in the mild category, 16.3% (26/160) in the moderate category, and 43.2% (19/44) in the severe category. Participants in the severe IPSS category showed high prevalence of dismobility (45.5%), multimorbidity (43.2%), malnutrition risk (40.9%), sarcopenia (40.9%), and polypharmacy (31.8%). According to erectile confidence based on the first IIEF-5 question, the prevalence of frailty was 18.7% (56/300) for low confidence, 5.3% (6/114) for moderate confidence, and 5.1% (4/78) for high confidence. Participants with low confidence in erectile function showed high prevalence of sarcopenia (39.0%), multimorbidity (37.7%), dismobility (35.7%), malnutrition risk (33.3%), and polypharmacy (23.0%).

Conclusion

The prevalence of frailty and geriatric conditions was higher in older men with severe urologic symptoms. A frailty screening should be routinely administered in urology practices to identify older men who are vulnerable to treatment-related adverse events.

Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptom (LUTS) and erectile dysfunction (ED) are highly prevalent and negatively associated with the quality of life in older men.Citation1 The prevalence of moderate to severe LUTS is 46% in the United States, with an increasing prevalence and severity into the 5th decade of life.Citation2 Meanwhile, ED affects 30% of men in their 60sCitation3 and over 80% of those in their 80s.Citation4 These symptoms can negatively affect the activity levelCitation5 and increase the risk of falls.Citation6 ED is also associated with cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, depressive symptoms, and poor quality of life.Citation7,Citation8

While proper treatments of LUTS and ED can improve the well-being of older men,Citation9 they are not without risks.Citation6,Citation10,Citation11 Medications for LUTS, such as alpha-blockers and antimuscarinics, can worsen orthostatic hypotension and cognitive impairment.Citation10 Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) can increase the risk of bleeding, delirium, and TURP syndrome, which is associated with morbidity, mortality, prolonged hospitalization, and costs.Citation12,Citation13 These risks may be particularly elevated in older men with frailty,Citation14 that is, in individuals who have decreased physiologic reserve and increased vulnerability to acute stressors. Therefore, recognizing frailty and geriatric syndromes in older men with urologic symptoms is crucial for the optimal management and prevention of treatment-related adverse events. However, the burden of frailty and geriatric conditions in community-dwelling older men with urologic symptoms is unknown.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to evaluate the burden of frailty and geriatric conditions according to the severity of LUTS and ED in community-dwelling older men. We administered two widely used questionnaires to assess LUTS and ED, the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and the five-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5),Citation15,Citation16 respectively. We hypothesized that severe symptoms of LUTS and ED are associated with frailty and geriatric syndromes.

Patient and methods

Study population

The Aging Study of PyeongChang Rural Area (ASPRA) is a population-based, prospective cohort study of frailty and geriatric syndromes in 1,350 community-dwelling older adults residing in PyeongChang, Gangwon, Korea.Citation17 The design and conduct of ASPRA cohort are described elsewhere.Citation17 Briefly, since the cohort was established in October 2014, participants have undergone annual assessments of medical, physical, and psychosocial status. The inclusion criteria for participation in ASPRA were 1) age ≥65 years; 2) registered in the National Healthcare Service; 3) ambulatory with or without an assistive device; 4) living at home; and 5) able to provide informed consent. Those who were living in a nursing home, hospitalized, or bed-ridden and receiving nursing-home-level care at the time of enrollment were excluded. The study enrolled 95% of eligible people in the study regions. The characteristics of ASPRA participants were overall similar to those of the Korean rural population represented in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.Citation17 Of the total of 498 men who completed the comprehensive geriatric assessment between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2016, 492 (98.8%) were assessed for LUTS and ED. The protocol of this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Asan Medical Center. All the participants provided written informed consent.

Urologic questionnaires

The IPSS and IIEF-5 questionnaires were administered to the participants by male physicians in a privacy-protected area.

IPSS urologic questionnaires

The IPSS is a widely used questionnaire for screening, diagnosis, and monitoring of the symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia and LUTS.Citation15 It consists of seven questions regarding voiding symptoms and one question on quality of life, with a scoring range of 0–35. We classified the participants into mild (0–7 points), moderate (8–19 points), and severe (20–35 points) categories.Citation1

IIEF-5

We evaluated sexual desire (ie, libido) and ED using a five-item version of the IIEF (also known as the Sexual Health Inventory for Men)Citation16 with a scoring range of 5–25. However, since many participants were not sexually active, we focused on the first IIEF-5 question – “How do you rate your confidence that you could get and keep an erection?” – that assesses the confidence in the erectile function, regardless of their sexual activity. Based on the first IIEF-5 question, we classified the participants as low (1–2 points), moderate (3 points), or high confidence (4–5 points).

Frailty assessment

Frailty was assessed according to the Cardiovascular Health Study frailty criteria, a widely validated definition for frailty.Citation18 The frailty phenotype scale is calculated by assigning 1 point to the following five components that are relevant to a given individual:Citation18 1) exhaustion: moderate or most of the time during the last week, to either of the following: “I felt that everything I did was an effort” or “I could not get going”; 2) low activity: lowest quintile in physical activity level measured using International Physical Activity Questionnaires Short Form (below the 20th percentile cutoff point in a representative sample of older Koreans in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [KNHANES]); 3) slowness: usual gait speed <0.8 m/s from 4-m walk test; 4) weakness: dominant handgrip strength <26 kg for men, <17 kg for women; and 5) weight loss: unintentional weight loss >3 kg during previous 6 months.Citation19,Citation20,Citation33 On the basis of the total score, individuals were classified as robust (0 points), prefrail (1–2 points), or frail (3–5 points).

Other measurements

Trained nurses performed a comprehensive geriatric assessment to evaluate the common geriatric conditions and use of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) medications (alpha-blockers, 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors, or anticholinergics). Multimorbidity was defined as having five or more of the 11 diagnoses (angina, arthritis, asthma, cancer excluding minor skin cancer, chronic lung disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, heart attack, hypertension, kidney disease, and stroke). Sarcopenia was defined according to the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia using a bioimpedance analysis.Citation17 Polypharmacy was defined as taking five or more prescription medications. Low cognition was defined as a Korean version of Mini-Mental-State Examination score <24.Citation21 Depressive mood was defined as a Korean version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale score >20.Citation22 Slow gait was defined as a usual gait speed <0.6 m/s from a timed 4-m walk.Citation23 Malnutrition risk was defined as a score of ≤11 according to the Mini-Nutritional Assessment-Short Form.Citation24 Disability was defined as requiring assistance in performing any of the seven activities of daily living (ADL; bathing, continence, dressing, eating, toileting, transferring, and washing face and hands) or 10 instrumental activities of daily living (IADL; food preparation, household chores, going out a short distance, grooming, handling finances, laundry, managing own medications, shopping, transportation, and using a telephone).Citation25

Statistical analysis

We summarized the characteristics of our study participants according to the mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. We evaluated the prevalence of the frailty phenotype and its components according to the severity categories of the IPSS and the first IIEF-5 question. The proportion of frailty and its component was compared across the severity category using a logistic regression to adjust for age. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of frailty across the severity category were also estimated. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

The mean age of the 492 men was 74.2 years (standard deviation: 5.6) (). Most men were prefrail (73.2%) or frail (13.4%), and multimorbidity (32.5%), low cognition (16.7%), IADL disability (15.7%), and fall history (13.0%) were common. The most prevalent underlying diseases diagnosed by physicians were hypertension (48.8%), arthritis (22.6%), diabetes (17.3%), heart disease (11.2%) and chronic lung disease (7.5%). Alpha-blockers, 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors, or anticholinergics were used by 117 men (23.8%). The IPSS questionnaire classified 288 men (58.5%) as mild, 160 (32.5%) as moderate, and 44 (8.9%) as severe for LUTS symptoms. According to the first IIEF-5 question, which assesses the confidence in erectile function, 300 men (61.0%) had low confidence.

Table 1 Characteristics of male participants in the Aging Study of PyeongChang Rural Area

Frailty and its components by IPSS and the first IIEF-5 question scores

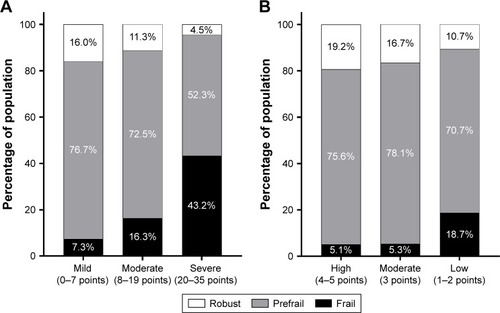

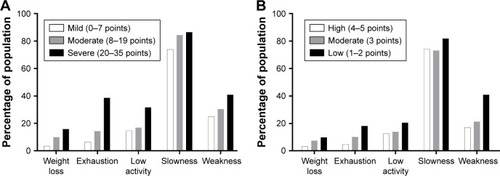

The prevalence of frail and prefrail states increased with greater IPSS severity (). Frailty was present in 21 of the 288 men (7.3%) with mild symptoms, 26 of the 160 men (16.3%) with moderate symptoms (OR: 2.47; 95% CI: 1.34–4.55; p=0.004), and 19 of the 44 men (43.2%) with severe symptoms (OR: 9.66; 95% CI: 4.59–20.33; p<0.001). Similarly, the prevalence of frailty was higher in the lower erectile confidence categories according to the first IIEF-5 question (). Frailty was identified in four of 78 men with high confidence (5.1%), six of 114 men (5.3%) with moderate confidence (OR: 1.03; 95% CI: 0.28–3.77; p=0.967), and 56 of 300 men (18.7%) with low confidence (OR: 4.25; 95% CI: 1.49–12.10; p=0.007). Each component of frailty increased in prevalence with higher severity according to IPSS () or the first IIEF-5 question ().

Figure 1 Frailty status according to IPSS category (A) and the first IIEF-5 question (B).

Notes: IIEF-5 first question asks participants, “How do you rate your confidence that you could get and keep an erection?” (A) LUTS from IPSS category; (B) Erectile confidence from the first IIEF-5 question; Frailty status was defined by Cardiovascular Health Study frailty criteria. We defined 0–7 points of IPSS score as “mild”, 8–19 points as “moderate”, and 20–35 points as “severe” LUTS. We also defined 4 or 5 points of the first IIEF-5 question as “high”, 3 points as “moderate”, and 1 or 2 as “low” erectile confidence.

Abbreviations: IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; IIEF-5, five-item version of International Index of Erectile Function; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptom.

Figure 2 Frailty components according to IPSS category (A) and the first IIEF-5 question (B).

Abbreviations: IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; IIEF-5, five-item version of International Index of Erectile Function; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptom.

Common geriatric conditions according to IPSS and the first IIEF-5 question scores

We also investigated the common geriatric conditions according to the severity as determined by each urologic questionnaire (). The prevalence of most geriatric conditions was higher as the severity of LUTS increased. Close to a half of the individuals with severe IPSS symptoms had dismobility (45.5%), multimorbidity (43.2%), malnutrition risk (40.9%), or sarcopenia (40.9%). The severe LUTS group showed significantly high prevalence of multimorbidity (43.2% of severe LUTS group; 43.1% of moderate group; 25.0% of mild group; p<0.001), polypharmacy (31.8% of severe LUTS group; 21.3% of moderate group;14.9% in mild group; p=0.015), and the mean number of regular medications taken regularly (3.6 tablets [SD 3.5] in severe LUTS group; 2.7 tablets [SD 2.7] in moderate group; 2.0 tablets [SD 2.4] in mild group, p<0.001) than low LUTS group.

Table 2 Common geriatric syndromes according to IPSS category and first IIEF-5 question in the Aging Study of PyeongChang Rural Area

Similarly, geriatric conditions were more prevalent in those with low erectile confidence: sarcopenia (39.0%), multimorbidity (37.7%), dismobility (35.7%), and malnutrition risk (33.3%) were common. Compared to the group of high confidence of erectile function, the group of low confidence of erectile function showed significantly high prevalence of multimorbidity (37.7% in the group of low confidence of erectile function; 24.6% in the group of moderate confidence; 24.4% in the group of high confidence; p=0.010), polypharmacy (23.0% in the group of low confidence of erectile function; 11.4% in the group of moderate confidence; 11.5% in the group of high confidence; p=0.006), and the mean number of medications taken regularly (2.8 tablets [SD 2.9] in the group of low confidence of erectile function; 1.8 tablets [SD 2.2] in the group of moderate confidence; 2.7 tablets [SD 2.1] in the group of high confidence; p<0.001).

Discussion

A majority of patients seeking medical or surgical treatment for moderate or severe LUTS are older men, and our study indicates that almost a half of these patients satisfy the criteria for frailty. Given that frail older adults may have increased vulnerability to treatment-related adverse events, our findings suggest the importance of recognizing frailty in older men with severe LUTS symptoms through a validated frailty assessment in the management of urological symptoms in these patients.

Medications are a primary treatment option in older men with moderate to severe LUTS. However, several medications used to treat LUTS can increase the risks of confusion, falls, and possibly mortality.Citation10,Citation14 Alpha-1 blockers, especially doxazosin, terazosin, and prazosin, should be avoided in older men with syncope, due to the risk of orthostatic hypotension. Antimuscarinics such as oxybutynin should be avoided in older patients with delirium, cognitive impairment, dementia, and Parkinson disease, due to their strong anticholinergic effects. Desmopressin, often used to treat nocturia or nocturnal polyuria, can increase the risk of hyponatremia. Based on these facts, the 2015 American Geriatric Society Beers Criteria recommended these medications be avoided or used with caution.Citation26 Oelke et al also warned of the potential harm of LUTS medication based on efficacy, safety, and tolerability.Citation10 In treating ED, discontinuation of certain culprit medications, such as antidepressants, diuretics, and beta-blockers, can help ED, but it might also exacerbate the comorbidity conditions.Citation27 Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors should be prescribed with caution in men with angina or coronary artery disease, which, it should be noted, are often undiagnosed in older patients. Dyspepsia, headache, flushing, visual disturbance, and drug–food interactions, meanwhile, are other potentially important issues.Citation27 According to several reports and experts, the risk of these adverse events may be higher in frail older adults.Citation28–Citation30

In cases where medications are not effective, surgical procedures are considered. Surgical procedures in older men, however, can be associated with adverse events. Approximately 15%–20% of patients undergoing TURP experience significant complications such as bleeding, clot retention, perforation of the prostate capsule, urinary tract infection, and post prostatectomy syndrome, and 0.2%–2.5% die.Citation13 In a Veterans Administration study, 9% of subjects had perioperative complications, including the need for placement of another urinary catheter, perforation of the prostate capsule, hemorrhage requiring transfusion, urinary tract infections, and thrombophlebitis.Citation31 Other studies have revealed that older men were more likely than younger men to develop TURP syndrome and delirium.Citation12 These complications negatively affect the quality of life and increase medical costs.Citation13 Frailty was strongly associated with the risk of postoperative complications after nearly all urologic surgery or procedures (adjusted OR 1.74; 95% CI: 1.64–1.85).Citation14,Citation32

Because frail older men may be at high risk of adverse events from LUTS or ED treatment, our results indicate the importance of recognizing frailty in the management of common urological symptoms in older men. In geriatrics, a number of frailty instruments have been developed and validated. Some of the widely validated instruments include the frailty phenotype, a deficit accumulation of frailty index, and the FRAIL (Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illnesses, Loss of weight) scale. The frailty phenotype that we used was developed from a large community-based cohort of older adults in the United StatesCitation18,Citation32 and subsequently validated in several other populations.Citation33–Citation35 It is based on the assessment of five specific components that require certain skills and administration time (in our experience, 10–15 minutes). The frailty index developed by Rockwood and Mitnitski originated from a large population-based Canadian cohort.Citation36 It calculates the proportion of deficits from a total of 30–90 health deficit variables. Rather than these extensive evaluations, we recommend that urologists and primary care physicians adopt the FRAIL scale, which is a brief screening tool based on five self-reported items.Citation37 This has been validated for the US,Citation37 European,Citation38 and Asian populations.Citation39 It classifies participants as robust (0 points), prefrail (1–2 points), or frail (3–5 points). This questionnaire does not require a physical examination and can be administered within 3 minutes.Citation39 Frailty screening improves prediction of older adults at high risk for poor surgical outcomes,Citation40–Citation43 but few studies examined this in older men undergoing urological procedures.Citation14,Citation32 Further studies are warranted to define the role of frailty screening in determining the risk–benefit of the urological procedures in older men.

There are several strengths and limitations to our study. The ASPRA is a population-based prospective cohort study that administered standardized measurements for frailty and an extensive list of geriatric syndromes in addition to the IPSS and IIEF-5 questionnaires.Citation17 Because our study population had a high participation rate of eligible men residing in the study regions, selection bias due to non-participation is unlikely. Although the ASPRA cohort was based on a rural community in Korea, we previously showed that their demographic characteristics are similar to a nationally representative sample.Citation17 However, the results from this study may not be generalized to nursing homes or populations of other ethnic origins. As a cross-sectional study, we were not able to determine whether the IPSS scores and the response to the first IIEF-5 question can predict the future development of frailty in older men and whether frailty can predict the worsening of urological symptoms in the future. The long-term follow-up data from the ASPRA cohort will be valuable to answer these clinically important questions.

Conclusion

Our study underscores the high prevalence of frailty and geriatric syndromes in older men with severe LUTS or ED. Considering the high prevalence of frailty and its clinical implications, urologists and primary care physicians should consider adopting a simple frailty screening tool for identifying frail older patients who may require careful assessment of benefits and risks of medical and surgical management options for their urological symptoms. Future research on whether a frailty screening and subsequent management based on frailty assessment improve patient-centered care and clinical outcomes in these patients is needed.

Author contributions

All the authors participated in design and study conception, performed statistical analysis, data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. All the authors read and revised this manuscript. This manuscript is the final approved version by all authors. All the authors have reviewed and agreed to be responsible for the process, accuracy, and integrity of all the parts of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to public health professionals and nurses of PyeongChang County Hospital, Public Health Center, and Community Health Posts for their administrative support and effort in enrollment and measurements. Public health professionals and nurses of PyeongChang County Hospital were involved in data collection, but they did not have any role in the study design, analysis or interpretation of data, writing of the paper, or decision to submit the paper for publication.

The ASPRA was supported by PyeongChang County Hospital, PyeongChang County, Gangwon Province, Korea. This study was also supported, in part, by Paul Park and Maeil Dairies Co., Ltd., and by the Asan Institute for Life Sciences and Corporate Relations of the Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. Paul Park and Maeil Dairies Co., Ltd., and the Asan Medical Center did not have any role in the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing of the paper, or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Dr Hee-Won Jung is supported by a Global PhD Fellowship Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2015H1A2A1030117). Dr Dae Hyun Kim is supported by the Paul B Beeson Clinical Scientist Development Award in Aging (K08AG051187) from the National Institute on Aging, American Federation for Aging Research, The John A Hartford Foundation, and The Atlantic Philanthropies.

Disclosure

Dr Dae Hyun Kim is a consultant to Alosa Health, a nonprofit educational organization with no relationship to any drug or device manufacturer. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SagnierPPMacFarlaneGTeillacPBottoHRichardFBoylePImpact of symptoms of prostatism on level of bother and quality of life of men in the French communityJ Urol19951533 Pt 16696737532230

- TaylorBCWiltTJFinkHAPrevalence, severity, and health correlates of lower urinary tract symptoms among older men: the MrOS studyUrology200668480480917070357

- RosenRCFisherWAEardleyIThe multinational men’s attitudes to life events and sexuality (MALES) study: I. Prevalence of erectile dysfunction and related health concerns in the general populationCurr Med Res Opin200420560761715171225

- SeftelADErectile dysfunction in the elderly: epidemiology, etiology and approaches to treatmentJ Urol200316961999200712771705

- HunterDJMcKeeMBlackNASandersonCFHealth status and quality of life of British men with lower urinary tract symptoms: results from the SF-36Urology19954569629717539561

- MorrisVWaggALower urinary tract symptoms, incontinence and falls in elderly people: time for an intervention studyInt J Clin Pract200761232032317263719

- MalavigeLSJayaratneSDKathriarachchiSTSivayoganSRanasinghePLevyJCErectile dysfunction is a strong predictor of poor quality of life in men with type 2 diabetes mellitusDiabet med201431669970624533738

- SanchezEPastuszakAWKheraMErectile dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risks: facts and controversiesTransl Androl Urol201761283628217448

- AraiYAokiYOkuboKImpact of interventional therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia on quality of life and sexual function: a prospective studyJ Urol200016441206121110992367

- OelkeMBecherKCastro-DiazDAppropriateness of oral drugs for long-term treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in older persons: results of a systematic literature review and international consensus validation process (LUTS-FORTA 2014)Age Ageing201544574575526104505

- LucenteforteELombardiNVetranoDLInappropriate pharmacological treatment in older adults affected by cardiovascular disease and other chronic comorbidities: a systematic literature review to identify potentially inappropriate prescription indicatorsClin Interv Aging2017121761177829089750

- XuePWuZWangKTuCWangXIncidence and risk factors of postoperative delirium in elderly patients undergoing transurethral resection of prostate: a prospective cohort studyNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20161213714226834475

- RiekenMEbinger MundorffNBonkatGWylerSBachmannAComplications of laser prostatectomy: a review of recent dataWorld J Urol2010281536220052586

- SuskindAMWalterLCJinCImpact of frailty on complications in patients undergoing common urological procedures: a study from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement databaseBJU Int2016117583684226691588

- AbramsPChappleCKhourySEvaluation and treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in older menJ Urol20131891 SupplS93S10123234640

- RosenRCCappelleriJCSmithMDLipskyJPenaBMDevelopment and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunctionInt J Impot Res199911631932610637462

- JungHWJangIYLeeYSPrevalence of frailty and aging-related health conditions in older Koreans in rural communities: a cross-sectional analysis of the Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural AreaJ Korean Med Sci201631334535226952571

- FriedLPTangenCMWalstonJFrailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotypeJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2001563M146M15611253156

- Avila-FunesJAAmievaHBarberger-GateauPCognitive impairment improves the predictive validity of the phenotype of frailty for adverse health outcomes: the three-city studyJ Am Geriatr Soc200957345346119245415

- FukutomiEOkumiyaKWadaTImportance of cognitive assessment as part of the “Kihon Checklist” developed by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare for prediction of frailty at a 2-year follow upGeriatr Gerontol Int201313365466223170783

- KangYNaDLHahnSA validity study on the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patientsJ Korean Neurol Assoc1997152300308

- ParkJHKimKWA review of the epidemiology of depression in KoreaJ Korean Med Assoc2011544362369

- CummingsSRStudenskiSFerrucciLA diagnosis of dismobility – giving mobility clinical visibility: a Mobility Working Group recommendationJAMA2014311202061206224763978

- RubensteinLZHarkerJOSalvaAGuigozYVellasBScreening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF)J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2001566M366M37211382797

- WonCWYangKYRhoYGThe Development of Korean Activities of Daily Living (K-ADL) and Korean Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL) ScaleJ Korean Geriatr Soc200262107120

- By the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert PanelAmerican Geriatrics Society 2015 updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc201563112227224626446832

- FinkHAMac DonaldRRutksIRNelsonDBWiltTJSildenafil for male erectile dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysisArch Intern Med2002162121349136012076233

- WaggAGibsonWOstaszkiewiczJUrinary incontinence in frail elderly persons: Report from the 5th International Consultation on IncontinenceNeurourol Urodyn201534539840624700771

- TannenbaumCHow to treat the frail elderly: the challenge of multimorbidity and polypharmacyCan Urol Assoc J201379–10 Suppl 4S183S18524523840

- LandiFRussoALiperotiRAnticholinergic drugs and physical function among frail elderly populationClin Pharmacol Ther200781223524117192773

- WassonJHRedaDJBruskewitzRCElinsonJKellerAMHendersonWGA comparison of transurethral surgery with watchful waiting for moderate symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Transurethral Resection of the ProstateN Engl J Med1995332275797527493

- CleggAYoungJIliffeSRikkertMORockwoodKFrailty in elderly peopleLancet2013381986875276223395245

- JungHWKimSWAhnSPrevalence and outcomes of frailty in Korean elderly population: comparisons of a multidimensional frailty index with two phenotype modelsPLoS One201492e8795824505338

- Garcia-GarciaFJGutierrez AvilaGAlfaro-AchaAThe prevalence of frailty syndrome in an older population from Spain. The Toledo Study for Healthy AgingJ Nutr Health Aging2011151085285622159772

- BieniekJWilczynskiKSzewieczekJFried frailty phenotype assessment components as applied to geriatric inpatientsClin Interv Aging20161145345927217729

- RockwoodKMitnitskiAFrailty in relation to the accumulation of deficitsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200762772272717634318

- MorleyJEMalmstromTKMillerDKA simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African AmericansJ Nutr Health Aging201216760160822836700

- BrooksREuroQol: the current state of playHealth Policy1996371537210158943

- JungHWYooHJParkSYThe Korean version of the FRAIL scale: clinical feasibility and validity of assessing the frailty status of Korean elderlyKorean J Intern Med201631359460026701231

- LinHSWattsJNPeelNMHubbardREFrailty and post-operative outcomes in older surgical patients: a systematic reviewBMC Geriatr201616115727580947

- HallDEAryaSSchmidKKAssociation of a frailty screening initiative with postoperative survival at 30, 180, and 365 daysJAMA Surg2017152323324027902826

- GleasonLJBentonEAAlvarez-NebredaMLWeaverMJHarrisMBJavedanHFRAIL questionnaire screening tool and short-term outcomes in geriatric fracture patientsJ Am Med Dir Assoc201718121082108628866353

- Dal MoroFMorlaccoAMotterleGBarbieriLZattoniFFrailty and elderly in urology: Is there an impact on post-operative complications?Cent European J Urol2017702197205