?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Purpose

Water balance disorders are associated with a high risk of death in elderly patients. The role of osmotic stress intensity and its direction toward hypo- or hypernatremia is a matter of controversy regarding patients’ survival. The aims of this study were, first, to measure the frequency of cellular hydration disorders in patients over 75 years old hospitalized in nephrology department for reversible acute renal failure, and second, to compare the impact of hyperhydration and hypohydration on the risk of death at 6 months.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively studied the data of 279 patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), aged 75 years or older, with pre-renal azotemia who experienced dysnatremia. We classified them according to natremia levels and compared their outcome in univariate and multivariate analysis.

Results

The patients were on average 83.2±5.4 years old. Among them, 128 were normonatremic, 82 were hyponatremic and 69 were hypernatremic. Osmotic stress intensity appreciated by the variation rate of natremia did not differ significantly between hyper- and hyponatremic patients. Patients had CKD stage 3B and 4 with acute kidney injury (AKI) of different severities. We observed that only hypernatremia was linked to death in the first 6 months following hospital discharge.

Conclusion

Hypernatremia is a strong predictor of fatal outcome in elderly patients suffering from chronic kidney impairment and referred for pre-renal azotemia.

Introduction

Water balance disorders are commonly found in hospitalized patients, most specifically in the elderly,Citation1,Citation2 and are associated with an increased risk of death.Citation3,Citation4 The kidneys play a major role in the regulation of body water, as illustrated by the higher rate of acute kidney injury (AKI) among patients suffering from hypernatremia.Citation5 However, it is not clear whether dysnatremias are causes or surrogate markers of underlying diseases. Indeed, hyponatremia has been associated with poor outcome in psychiatric inpatientsCitation6 and in patients suffering from pulmonary tract infections.Citation7 Hypernatremia has been related to increased mortality following bacterial infectious diseasesCitation8 and cerebrovascular injuries.Citation9 Moreover, the role of the direction toward hypo- and hypernatremia and the severity of dysnatremia remains to be clarified. Actually, hypernatremia increases seven times the risk of death,Citation10 whereas hyponatremia doubles this risk,Citation11 as compared to age-matched normonatremic patients. Consequently, one would attribute an overwhelming role to the direction of dysnatremia irrespective of its severity. In contrast, mortality-related dysnatremia follows a U-shaped curve indicating increased mortality risk for extreme dysnatremia. This pattern is established both in intensive care patientsCitation12,Citation13 and in a cohort of veterans suffering from chronic kidney disease (CKD).Citation14 Accordingly, the intensity of osmotic stress would be expected to play a major role regardless of its direction toward hypo- or hypernatremia. Taking advantage of the high incidence of dysnatremia observed in CKD patients experiencing pre-renal azotemia, we seek to provide a better insight into this issue. Therefore, we retrospectively compared the outcome of patients with hypo- and hypernatremia of similar severity to the outcome of normonatremic patients.

Patients and methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the “Sud Méditerranée” Institutional Review Board. This protection committee waived the need for ethical approval and for written informed consent in this retrospective study with no potential for harm to subjects. Nevertheless, an information form on the use of their data for research purposes has been sent to patients. The lack of a negative response from them within a month was considered as their agreement. To ensure patient’s privacy, all details were collected in an anonymized database.

We retrospectively studied the data of CKD patients aged 75 years or older who were referred to our nephrology department for pre-renal azotemia over a 5-year time period. One of the parameters studied was osmotic stress. We estimated the intensity of the osmotic stress for hyper- and hyponatremia according to the following formula:

In this formula, “extreme” indicates minimal or maximal value during hospital stay, while “discharge” indicates value at hospital discharge. Serum creatinine (SCr) at discharge was used for the staging of CKDCitation15 according to the simplified formula from the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD).Citation16 Following the current recommendations,Citation17 the severity of AKI was characterized according to the ratio between the highest SCr level and the discharge SCr level:

Disability was assessed according to the dependence from the nursing team and/or to impaired mental status. Finally, the patients were classified according to their natremia levels (<135, 135–145 and >145 mmol/L) and outcomes were compared between groups in univariate and multivariate analysis. Results are presented as mean and SD values. Student’s t-tests or chi-squared tests were used for univariate analysis. We performed a multiple logistic regression in an attempt to identify independent predictors of death within the first 6 months after discharge. The predictors taken into account were age, sex, diabetes, bacterial infection, active neoplasia, length of hospital stay, CKD stage, severity of AKI and disability. The model was developed with a forward selection procedure of characteristics associated with death within the first 6 months after discharge, with cutoffs of P<0.05 for inclusion and P>0.10 for exclusion. Variables with more than two categories were introduced using dummy variables. Model adequacy was estimated by the likelihood ratio goodness-of-fit test. Probability values of <0.05 were accepted as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed on SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

There were 128 normonatremic patients (139.0±0.3 mmol/L), 82 hyponatremic patients (125.5±0.7 mmol/L) and 69 hypernatremic patients (153.6±0.9 mmol/L). On average, 279 patients were 83.2±5.4 years old. Results from univariate analysis are presented in . Osmotic stress intensity was not significantly different in hypo- and hypernatremic patients (−78±6 vs 70±8 AU). Dysnatremic patients had CKD stage 3B, whereas normonatremic ones had CKD stage 4. AKI was more severe in hypernatremic patients compared to normonatremic ones. However, the intensity of AKI was not significantly different in hyponatremic patients compared to normonatremic ones. Mortality within 6 months after discharge was significantly higher in hypernatremic patients (48%) compared to normo- (22%) and hyponatremic patients (29%). Hypernatremic patients were found to be more often disabled and to remain longer in hospital compared to normonatremic ones. These latter differences were not present in hyponatremic patients.

Table 1 Results from univariate analysis

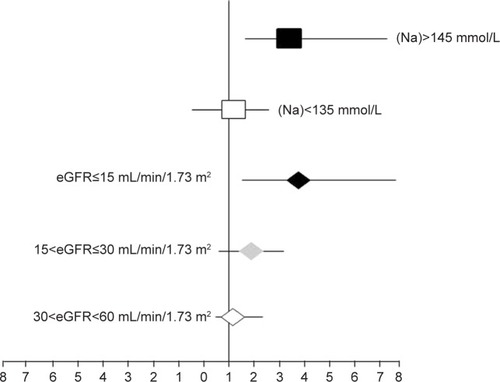

Results from multivariate analysis are presented in and . Hypernatremia was associated with an increased mortality (OR 3.4, CI 95% 1.6–7.1, P=0.001) but hyponatremia was not. CKD stage 5 was independently associated with an increased risk of death (OR 3.9, CI 95% 1.3–11.5, P=0.013).

Figure 1 ORs of death between admission and 6 months after discharge from hospital.

Abbreviation: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Table 2 Independent variables retained in the logistic regression equation: hypernatremia and eGFR≤15 mL/min/1.73 m2

Discussion

Because fatal outcome has been linked to the osmotic stress intensity independently from its orientation toward hypo- or hypernatremia,Citation13,Citation14 the importance of the direction of dysnatremia regarding mortality is controversial. In our study, we compared the outcome of elderly patients with acute and chronic impairment of kidney function experiencing hypo- and hypernatremia of similar severity. We observed that only hypernatremia was associated with an increased risk of death. Thus, the interpretation of our data differs from the established relationship between natremia and mortality which follows a U-shaped curve and indicates increased fatalities for extreme dysnatremia.Citation13,Citation14 In our study, mortality was not related to the osmotic stress levels, possibly because the perturbations were not intense enough to achieve statistical significance or because of an insufficient patient sample. Yet, in accordance with our study, the increased risk of death has been usually reported in hypernatremic patients. For example, Snyder et alCitation10 showed that hypernatremia-associated mortality was seven times higher than normonatremia-associated mortality in age-matched patients. Similar results have recently been demonstrated by Tsipotis et alCitation18 with increased in-hospital mortality and heightened resource consumption. Likewise, Cabassi and TedeschiCitation19 showed that the severity of community-acquired hypernatremia is an independent predictor of mortality. In this study, we found that 48% of our hypernatremic patients died within the first 6 months after hospital discharge. In the literature, the mortality rate of hypernatremia, which is usually assessed within the first 30 days, ranges from 41.5% to 66%.Citation5,Citation20,Citation21 In contrast, hyponatremia did not account for increased fatal events in our study. In line with this, the risk of death was found inconstantly increased in patients suffering from hyponatremia.Citation2,Citation4,Citation11,Citation14 Furthermore, the meta-analysis by Sun et alCitation22 highlights an increased all-cause mortality risk in CKD patients with both baseline hyponatremia and time-dependent hyponatremia or hypernatremia. However, these broad observations are not comparable to ours which concern only patients hospitalized for pre-renal azotemia. It should be noted that our study did not assess the severity of the osmotic stress on mortality. This would require a comparison among dysnatremias of same direction and different intensities.Citation8

It is not clear whether dysnatremia directly reduces survival or whether it is a surrogate marker of more severe disease states. As previously indicated, we found that a high mortality risk was independently associated in elderly patients with CKD stage 5.Citation23 Moreover, we observed that hypernatremic patients had more severe AKI with severity being directly related to higher risk of death.Citation17 Multivariate analysis was performed in an effort to identify independent factors predictive of mortality. However, our results were validated only for patients with CKD and AKI.

As expected, CKD patients with AKI are very likely to develop dysnatremia,Citation5 which can be explained by the central role of the kidneys in water balance regulation.Citation24 Urinary concentrating ability is decreased by both impairment of kidney function and age, predisposing to hypernatremia. Moreover, thirst, which is the main protective response against hypernatremia, is blunted in aging.Citation25 On the other hand, CKD is responsible for an increase in water retention,Citation26 which typically occurs in patients with pre-renal azotemia who experience increased levels of thirst. Of note, in the situation of advanced CKD stages, we observed more patients with hyponatremia than with hypernatremia. In contrast, in a cohort of veterans suffering from CKD of several severities, hypernatremia prevalence varies directly with CKD stages. In our study, this discrepancy may be attributed to the hospitalization for AKI.

Conclusion

Overall, our retrospective study shows a high frequency of water balance disorders in elderly patients with CKD and AKI. In this frail population, hypernatremia is associated with an increased rate of mortality, but hyponatremia with osmotic stress of similar severity is not.

Author contributions

CG-C contributed to analysis and interpretation of biostatistical data and preparation of the manuscript. MD contributed to selection of subjects and data collection. VLME provided comments for the design of the study and contributed to manuscript preparation. GF contributed to concept and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Sonia Doi for reviewing the manuscript and helpful comments. The abstract of this paper was presented at the 18th Annual Meeting of French Society of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, April 22–24, 2014, Poitiers, France, as a poster presentation/conference talk with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in “Discussed Poster Abstracts” in Fundamental and Clinical Pharmacology, Volume 28, Issue s1, May 2014: DOI:10.1111/fcp.12065. There was no sponsor involved in this study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HawkinsRCAge and gender as risk factors for hyponatremia and hypernatremiaClin Chim Acta20033371–216917214568195

- FrenkelWNvan den BornBJvan MunsterBCKorevaarJCLeviMde RooijSEThe association between serum sodium levels at time of admission and mortality and morbidity in acutely admitted elderly patients: a prospective cohort studyJ Am Geriatr Soc201058112227222821054304

- PalevskyPMBhagrathRGreenbergAHypernatremia in hospitalized patientsAnn Intern Med199612421972038533994

- WaikarSSMountDBCurhanGCMortality after hospitalization with mild, moderate, and severe hyponatremiaAm J Med2009122985786519699382

- ChassagnePDruesneLCapetCMénardJFBercoffEClinical presentation of hypernatremia in elderly patients: a case control studyJ Am Geriatr Soc20065481225123016913989

- ManuPRayKReinJLde HertMKaneJMCorrellCUMedical outcome of psychiatric inpatients with admission hyponatremiaPsychiatry Res20121981242722424891

- ZilberbergMDExuzidesASpaldingJHyponatremia and hospital outcomes among patients with pneumonia: a retrospective cohort studyBMC Pulm Med200881618710521

- BorraSIBeredoRKleinfeldMHypernatremia in the aging: causes, manifestations, and outcomeJ Natl Med Assoc19958732202247731073

- MillerPDKrebsRANealBJMcintyreDOHypodipsia in geriatric patientsAm J Med19827333543567124762

- SnyderNAFeigalDWArieffAIHypernatremia in elderly patients. A heterogeneous, morbid, and iatrogenic entityAnn Intern Med198710733093193619220

- TerzianCFryeEBPiotrowskiZHAdmission hyponatremia in the elderly: factors influencing prognosisJ Gen Intern Med19949289918164083

- DarmonMDiconneESouweineBPrognostic consequences of borderline dysnatremia: pay attention to minimal serum sodium changeCrit Care2013171R1223336363

- FunkGCLindnerGDrumlWIncidence and prognosis of dysnatremias present on ICU admissionIntensive Care Med201036230431119847398

- KovesdyCPLottEHLuJLHyponatremia, hypernatremia, and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease with and without congestive heart failureCirculation2012125567768422223429

- LeveyASEckardtKUTsukamotoYDefinition and classification of chronic kidney disease: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)Kidney Int20056762089210015882252

- LeveyASBoschJPLewisJBGreeneTRogersNRothDA more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study GroupAnn Intern Med1999130646147010075613

- KellumJALameireNKDIGO AKI Guideline Work GroupDiagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 1)Crit Care201317120423394211

- TsipotisEPriceLLJaberBLMadiasNEHospital-associated hypernatremia spectrum and clinical outcomes in an unselected cohortAm J Med20181311728228860033

- CabassiATedeschiSSeverity of community acquired hypernatremia is an independent predictor of mortality: a matter of water balance and rate of correctionIntern Emerg Med201712790991128669048

- HimmelsteinDUJonesAAWoolhandlerSHypernatremic dehydration in nursing home patients: an indicator of neglectJ Am Geriatr Soc19833184664716875149

- MandalAKSaklayenMGHillmanNMMarkertRJPredictive factors for high mortality in hypernatremic patientsAm J Emerg Med19971521301329115510

- SunLHouYXiaoQDuYAssociation of serum sodium and risk of all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: A meta-analysis and systematic reviewSci Rep2017711594929162909

- CouchoudCLabeeuwMMoranneOA clinical score to predict 6-month prognosis in elderly patients starting dialysis for end-stage renal diseaseNephrol Dial Transplant20092451553156119096087

- KovesdyCPSignificance of hypo- and hypernatremia in chronic kidney diseaseNephrol Dial Transplant201227389189822379183

- AdroguéHJMadiasNEHypernatremiaN Engl J Med2000342201493149910816188

- AdroguéHJMadiasNEHyponatremiaN Engl J Med2000342211581158910824078