Abstract

Background

Despite their adverse effects, antipsychotics are frequently used to manage behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Regular monitoring of antipsychotic prescribing has been shown to improve the appropriateness of prescribing. However, there is currently no consensus on what the components of such a monitoring tool would be.

Aim

The aim of this study was to use an expert consensus process to identify the key components of an antipsychotic repeat prescribing tool for use with people with dementia in a general practice setting.

Methods

A modified eDelphi technique was employed. We invited multidisciplinary experts in antipsychotic prescribing to people with dementia to participate. These experts included general practitioners (GPs), geriatricians and old age psychiatrists. The list of statements for round 1 was developed through a review of existing monitoring tools and international best practice guidelines. In the second round of the Delphi, any statement that had not reached consensus in the first round was presented for re-rating, with personalized feedback on the group and the individual’s response to the specific statement. The final round consisted of a face-to-face expert meeting to resolve any uncertainties from round 2.

Results

A total of 23 items were rated over two eDelphi rounds and one face-to-face consensus meeting to yield a total of 18 endorsed items and five rejected items. The endorsed statements informed the development of a structured, repeat prescribing tool for monitoring antipsychotics in people with dementia in primary care.

Conclusion

The development of repeat prescribing tool provides GPs with practical advice that is lacking in current guidelines and will help to support GPs by providing a structured format to use when reviewing antipsychotic prescriptions for people with dementia, ultimately improving patient care. The feasibility and acceptability of the tool now need to be evaluated in clinical practice.

Introduction

Most people living with dementia will experience behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) at some stage in the illnessCitation1 with some studies estimating that between 80% and 90% of people with dementia will experience at least one symptom of BPSD.Citation2 BPSD encompasses a wide range of noncognitive symptoms that affect people living with dementia and includes behaviors such as agitation or aggression and psychological symptoms such as anxiety or hallucinations. BPSD is associated with increased rates of admission to nursing homesCitation3 and longer in-patient hospital staysCitation4 and is a major contributor to caregiver stress and depression.Citation5 General practitioners (GPs) play a pivotal role in the care of people with dementia,Citation6,Citation7 providing the day-to-day medical care for people with dementia living in their own homes and in nursing homes. However, similar to their secondary care colleagues,Citation8 GPs can find the management of BPSD a particularly challenging aspect of dementia care.Citation9,Citation10 Non-pharmacological strategies are recommended as first-line treatment in BPSD.Citation11 Personalized non-pharmacological interventions such as personalized music therapyCitation12,Citation13 and formal caregiver training to enhance communication skillsCitation13 may have a role in the management of BPSD; however, the uptake of non-pharmacological strategies is low.Citation14 Psychotropic medication, in particular antipsychotics, are frequently employed to manage BPSD;Citation14 however, antipsychotics are not recommended unless there is a serious risk of harm to the person with dementia or others.Citation11 Antipsychotics have particular adverse effects in people with dementia including an increased risk of stroke and increased mortality.Citation15,Citation16 Furthermore, evidence suggests that antipsychotics are, at best, only minimally effective at improving BPSD.Citation15,Citation17 Despite their adverse effects and minimal effectiveness, antipsychotics are still prescribed to people with dementia experiencing BPSD.Citation18,Citation19 The rates of antipsychotic prescribing in people with dementia vary from country to country with rates as high as 29% in a 2013 audit conducted in IrelandCitation20 and lower rates of 17.7% in a comparable 2012 audit in the UK.Citation21 Nursing home residents, who typically have more advanced dementia, are significantly more likely to be on an antipsychotic medication than people with dementia living in their own homes,Citation20 up to five times as likely in one study.Citation19

The reason for continued prescribing of these potentially harmful medications is complex.Citation22 In the context of stretched resources, non-pharmacological alternatives to antipsychotic prescribing can be viewed as being impractical and not implementable.Citation23 The benefit of antipsychotic medication can be overestimated.Citation24 Furthermore, both GPs and consultant psychiatrists report that they sometimes feel under pressure from nursing home staff, and occasionally family caregivers, to prescribe medications.Citation8,Citation10 As a result, antipsychotics are sometimes employed to enable the person with dementia, their caregiver and the nursing home staff to cope with these behaviors and symptoms.Citation22

When prescribed for BPSD, antipsychotics should only be used on a short-term basis and should be reviewed for side effects and for effectiveness as many of the harmful side effects of antipsychotics are dose and duration dependent. However, there is evidence that antipsychotics are often inappropriately prescribed to people with dementia for prolonged periods of time,Citation18 sometimes without a documented indicationCitation25 and with suboptimal review processes.Citation26 A systematic review in 2014 examined interventions to reduce inappropriate prescribing of antipsychotic medications in care homes and identified a wide variety of interventions from educational interventions to organizational changes.Citation27 Medication review was identified as an intervention employed to reduce antipsychotic prescribing with some promising results.Citation27 Since that 2014 review, other studies have shown that regular monitoring of antipsychotic prescribing can reduce the overall prescribing of antipsychotics in dementiaCitation28 and improve the appropriateness of prescribing.Citation29 The WHELD study identified the value of antipsychotic review, demonstrating that it can lead to a 50% reduction in antipsychotic use in nursing homes.Citation28 However, it is also highlighted that to positively benefit the person with dementia any intervention to reduce antipsychotic medication needs to be supported by non-pharmacological interventions such as social interaction.Citation28

A recent qualitative study conducted by the authors explored the challenges GPs experience managing BPSD.Citation10 In the study participating GPs called for GP-specific guidance on the pharmacological management of BPSD. Guidance for GPs in the form of a repeat prescribing tool to monitor the prescribing of antipsychotics in dementia would facilitate the conduct of antipsychotic reviews in general practice. However, there is currently no consensus on what the components of such a tool would be.

The aim of this study was to use an expert consensus process to identify the key components of an antipsychotic repeat prescribing tool for use with people with dementia in a general practice setting.

Methods

Study design

A Delphi method was used to establish expert consensus that would inform the development of a repeat prescribing tool for GPs to use when monitoring people with dementia on antipsychotic medications. The Delphi is a “group facilitation technique that seeks to obtain consensus on the opinions of experts through a series of structured questionnaires” (known as rounds).Citation30 The key features of the Delphi method include the following: recruiting relevant experts for the study, compiling questionnaires with a list of statements that the experts rate for agreement, calculating the results, giving anonymized feedback to participants about how their responses compared to the rest of the group and giving participants the opportunity to revise their responses to the questionnaire in light of this feedback.Citation31 This iterative process continues over multiple rounds of questionnaires until consensus is reached, with some statistical criterion being used to define consensus. A modified Delphi was employed in this study, which combines the questionnaire with a physical meeting of experts to discuss the results.Citation32 This face-to-face meeting is recommended at the end of the last round to exchange views and resolve uncertainties and is, therefore, often considered to function as a final “round”.Citation32 We utilized a web-based platform to organize and facilitate communication. This eDelphi approach has practical advantages over the traditional paper-based Delphi model facilitating the participation of experts from different geographical locations and enabling faster response times.Citation33

Research steering group

The research team formed a research steering group. This consisted of the research facilitator (NG) and two GPs (TF, AAJ) both of whom have clinical and research expertise in the management of BPSD. The function of this working group was to review the literature to inform the development of the first round of the questionnaire and to participate in a final meeting once the eDelphi rounds were completed to discuss any uncertainties. The members of the research steering group did not complete the eDelphi questionnaires.

Selection and recruitment to the expert panel

Participants in the Delphi were purposively selected by the research team based on their known expertise in the area.Citation30 To ensure diversity, a panel of medical experts was recruited from different medical specialities to participate in the Delphi consensus. Medical professionals participating in the eDelphi included GPs, old age psychiatrists and geriatricians.

GPs were eligible to participate if they met the following inclusion criteria: minimum of 10 years as a practicing GP, regularly engaged in the management of patients with BPSD and providing care to people with dementia in a nursing home setting. GPs meeting these inclusion criteria were identified nationally. From this population, a sample of GPs was purposively selected to include GPs of different ages and with different practice locations (rural/urban) with the goal of achieving maximum variation. Consultant psychiatrists and consultant geriatricians were eligible to participate in the study if they provided care to people with BPSD in a nursing home setting and if they had a research interest in this area with relevant peer-reviewed publications. Once eligible participants were identified, they were individually emailed, provided with information on the study and invited to participate in the eDelphi.

Questionnaire development

The questionnaire was iteratively developed by the research steering group. The content of the questionnaire was informed by a review of existing antipsychotic drug-monitoring templates from the UK and CanadaCitation34–Citation36 and by a review of international guidance documents on antipsychotic prescribing in dementia.Citation37–Citation41

Analysis of rounds and consensus criteria

We asked the participants to state the extent to which they agreed with a list of statements using a 5-point Likert scale. The option to provide free text comments was provided throughout the questionnaire. The level of percentage agreement necessary to reach consensus for this particular study was informed by the literature on consensus criterion in Delphi processesCitation42 and by Delphi studies exploring similar research areas.Citation43–Citation45 In cases where a statement received ≥80% agreement, it was agreed that consensus had been reached. These statements were omitted from further rounds and were automatically included in the monitoring template. Any statement receiving <40% was rejected and, therefore, excluded from the monitoring template. All statements that fell between 40% and 79% agreement were deemed undecided, ie, had not reached consensus, so these statements were carried forward into the next round to be re-rated.

In the second round of the eDelphi, any statements that had not reached consensus in the first round were presented for re-rating using the same 5-point Likert scale. In this round, each participant was provided with individualized feedback which included the mean answer of the group response to each statement in round 1. In addition, the participant’s own response to the statements in round 1 was provided to illustrate their position in the group. This offered Delphi members an opportunity to revise and refine initial answers based on the group opinion. Free text comments provided by participants in round 1 were also included as statements in round 2 if the same suggestion was made by two or more participants. For each statement in the second round, it was decided that >70% agreement reached consensus to include the statement and <50% agreement reached consensus to exclude the statement.

Study ethics

Ethical approval was granted by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals. Participants were advised in an information sheet and in the initial e-mail they received, that the completion of the first round of the eDelphi was considered to be their consent to participate in the study.

Results

Study participation

A total of 17 medical professionals with expertise in dementia care were invited to participate, and 14 agreed to participate in the study. This group of 14 experts included the following: eight GPs, four old age psychiatrists and two geriatricians (the breakdown of the retention rate for each professional group is provided in ).

Table 1 Participants by professional group

Item ratings

A total of 23 items were rated over two rounds to yield a total of 18 endorsed items and five rejected items. summarizes the number of items rated, endorsed and rejected over the two eDelphi rounds.

Table 2 Statements that were accepted, rejected and re-rated at each stage

Round 1 questionnaire results

The first-round questionnaire consisted of 21 statements, and participants were asked to rate the statements using a 5-point Likert scale (). Surveys were open for completion for 2 weeks. Nine of the statements reached consensus and were endorsed in round 1. These statements were, therefore, included in the monitoring template and were excluded from the second-round survey. One statement received only 28.5% agreement, which was below the cutoff of 40%, so this statement was automatically excluded from the monitoring template and from any further rounds of questionnaire. Eleven statements did not reach consensus, rating between 40% and 79%; therefore, all these statements were included in round 2 for re-rating. All statements that were endorsed, rejected or did not reach consensus in round 1 are presented in .

Table 3 Round 1 statements with their associated consensus decisions

Qualitative feedback provided by participants in the free text comment boxes of round 1 was thematically analyzed. If a suggestion was made by two or more participants, it was included in the questionnaire for round 2. One suggestion made by two participants was that urinalysis or mid-stream urine (MSU) should be done as a baseline test prior to initiation of antipsychotic medication.

“… urinalysis should be a standard baseline test +/−MSU…” [old age psychiatrist 1]

“I would also do an MSU” [GP 1]

As a result of these comments, a statement on performing MSU analysis was included in the second-round questionnaire.

Another item that received several qualitative comments was the statement that recommended medical review should happen 6 weeks after the antipsychotic medication was commenced. Three participants suggested that medical review should occur earlier than this:

“Earlier initial review may be more appropriate, eg, 2–4 weeks” [old age psychiatrist 1]

“Should be reviewed within a month” [geriatrician 2]

“Review should be earlier than 6 weeks” [old age psychiatrist 2]

As a result of these comments, an additional statement was included in the questionnaire for round 2 stating that review should occur at 4 weeks. Even though the original statement that a review should occur at 6 weeks did achieve consensus in round 1, in light of the qualitative feedback, the research steering group decided to include the original statement again in the questionnaire for round 2.

The wording of one of the statements was modified based on the qualitative feedback provided by participants. The modified item was related to conducting a body mass index (BMI) measurement. Initially, the statement in the Delphi questionnaire was “The presence/absence of the following medication side-effects should be documented prior to repeat prescribing of antipsychotics in patients with dementia … increase in BMI”. This rating did not reach consensus in round 1, and concerns were raised about the practicality of measuring the BMI:

“BMI risk would not be high up my decision-making process given the typical patient profile…” [geriatrician 1]

“It would not be easy to weigh and measure a patient in a family home setting” [GP 2]

As a result, this question was modified to include the stem “where feasible” and was included in the second-round questionnaire for re-rating.

Finally, concern was raised as to the feasibility of performing an electrocardiograph (ECG) prior to commencing an antipsychotic:

“… Re ECG, this is very relevant, but not always possible – again, I do not do this routinely myself. And would you hold down a psychotic patient to do an ECG?” [geriatrician 1]

“… A baseline ECG could be difficult in a home setting” [GP 1]

This statement had not achieved consensus in round 1 (78.5% agreement), so it was included in the second-round questionnaire. In addition, these qualitative comments regarding the feasibility of conducting an ECG were included in the individualized feedback to participants in round 2.

Round 2 questionnaire results

The second-round questionnaire consisted of 13 statements: eleven statements that did not reach consensus in round 1 and 2 additional statements that were included in response to the qualitative comments provided by participants in round 1. Consensus was reached on 11 of the 13 statements in round 2. Details on each statement included in round 2 and the consensus outcome are given in . Nine statements achieved ≥70% agreement, and these statements were included in the monitoring template. Two statements were rejected as they achieved ≤50% agreement. Two statements did not reach consensus in round 2, but both statements reached a low percentage agreement of 54%. In the context of the low percentage agreement for these two statements and in view of the fact that a third round would include just two statements, these two statements were brought to the Delphi steering group for discussion. In a modified eDelphi, such a face-to-face consensus meeting is often considered to be an additional round.Citation32

Table 4 Round 2 statements with their associated consensus decisions

The first statement discussed by the research steering group was the statement on the documentation of an increase in BMI prior to repeating a prescription for an antipsychotic. After discussion with the steering group, this statement was rejected. The decision to exclude the statement was informed by the qualitative feedback in the Delphi rounds: a low percentage agreement of 54% in round 2 and a 17.4% reduction in percentage agreement from the first round to the second round. The second statement discussed at the meeting was the statement that after initiation of an antipsychotic, a patient should have a documented review by their GP within 4 weeks. This statement was added to round 2 after consideration of the qualitative feedback from round 1; however, it received only a 54% agreement rating in round 2. The conflicting statement, recommending review at 6 weeks, was endorsed in both round 1 and round 2 of the eDelphi. In this context, it was decided to reject this statement that review should occur within 4 weeks in favor of the statement that review should occur at 6 weeks.

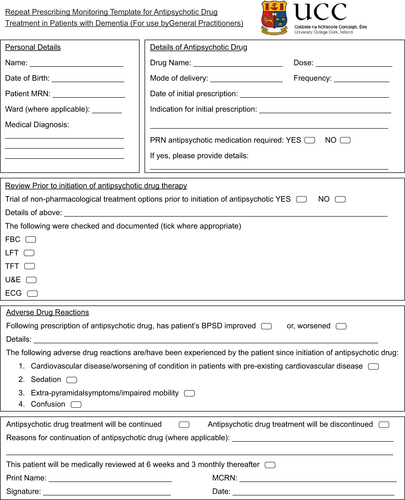

The combined consensus from round 1 and round 2 resulted in 18 statements that were endorsed by the expert panel. These 18 statements informed the content of an antipsychotic repeat prescribing tool for GPs to use when monitoring people with dementia on antipsychotics. The final tool was developed by the Delphi steering group as shown in Figure S1.

Discussion

This study utilized a modified eDelphi expert consensus process to inform the development of an antipsychotic repeat prescribing tool in people with dementia in a general practice setting. This repeat prescribing tool will provide GPs with a practical, relevant and implementable resource that will support them in monitoring their patients with dementia on antipsychotic medications.

A number of key issues regarding the challenges of monitoring antipsychotic prescribing in dementia were identified including the use of ECG, measurement of BMI and the scheduled time for the review of prescribing. The practical difficulties in obtaining an ECG prior to initiation of antipsychotic medication were highlighted by several participants in the qualitative feedback; however, it did ultimately achieve consensus in round 2 and was, therefore, included in the final tool. International guidelines do not specifically recommend performing an ECG;Citation37,Citation38,Citation41 however, given the propensity of nearly all antipsychotic medication to cause QT prolongation, it is a reasonable consideration, where practical, in advance of initiating these medications. Likewise, although BMI measurement is not recommended in the existing guidelines,Citation37,Citation38,Citation41 it was included as a statement for review in the eDelphi as antipsychotics are known to result in weight gain.Citation46 However, the difficulties in measuring BMI prior to initiation of an antipsychotic were highlighted by several participants, and this statement was eventually rejected in round 2.

One particularly contentious issue was the recommended time interval after an initial prescription for an antipsychotic during which a GP review of the effect of the medication should be undertaken, with some participants advocating for a review within 4 weeks instead of 6 weeks. However, the statement that a review should occur within 6 weeks was the statement that was ultimately endorsed. The existing guidelines do vary on this issue of when a review should occur after initiation of an antipsychotic medication in a person with dementia. For instance, the most recent 2018 National Institute for Clinical Evidence guidelines on dementia care recommend that initial treatment with an antipsychotic should use the lowest effective dose for the shortest time with a reassessment of the person at least every 6 weeks.Citation47 This is echoed in the American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2016 guidelines on antipsychotic medications in dementia which recommends a review of symptoms 4–6 weeks after initiation of an antipsychotic.Citation38 Guidance from Australia recommends that if there is no treatment efficacy within a relatively short timeframe (eg, 1–2 weeks), treatment should be discontinued.Citation41 Overall, in the different guidance documents, the recommended time between medication initiation and GP review of the effect of the medication ranges from 2 to 6 weeks. The different guidance documents do not distinguish between a person with dementia living at home from a person with dementia living in a nursing home setting. However, in a nursing home setting, residents are being observed by the nursing home staff; therefore, a GP review at 6 weeks may be acceptable. It is likely, however, that a person with dementia living at home would benefit from an earlier review.

One finding that was overwhelmingly rejected in round 1 was the statement that “medical review prior to initiation of antipsychotics for patients with dementia should include documented consent from patient with dementia/patient’s next of kin prior to initiation of drug therapy”. This statement was included in the original questionnaire for round 1 as both the NICE guidance and the APA guidance recommend discussing the benefits and potential harms with the person and their family members or carer prior to commencing an antipsychotic. The practical challenges of obtaining “documented consent” may have influenced the rejection of this statement, rather than a reluctance on the part of participants to discuss the risks and benefits with the person with dementia or their caregiver. Antipsychotics should only be prescribed if the person with dementia is a danger to either themselves or to others.Citation11 In these situations, it may not always be possible to obtain documented consent from either the person with dementia, who may not be able to give informed consent, or their family member, who may not be available.

Comparison with existing literature

The Delphi consensus approach has been used successfully to develop criteria for potentially inappropriate medication in people nearing the end of life.Citation48 More specifically, Delphi studies have been used previously to address the issue of potentially inappropriate prescribing of medication to people with dementia.Citation49–Citation54 However, we are unaware of any existing literature that used a consensus development method to inform the development of an antipsychotic repeat prescribing tool for use in people with dementia. Previously, a modified eDelphi consensus procedure was used to develop practice guidelines on the prescription of antipsychotics to people with dementia living in care homes.Citation55 The majority of clinicians participating in that expert panel were old age psychiatrists; however, the views of geriatricians and GPs were incorporated. Although the study did not develop a repeat prescribing tool it did address certain issues surrounding antipsychotic initiation and review. The results largely echoed our study results, however, there were some notable differences. These differences centered on the consensus reached on the consultation that should take place with family caregivers and on conducting ECGs prior to initiating antipsychotic medication. First, the study recommended that ECG was only necessary in patients with a history of cardiovascular disease or if the patient was on another medication that can prolong the QT interval. Second, the study affirmed that the patient (if appropriate) and the primary family caregiver should be consulted in the critical phases of treatment, specifying that they should be consulted pre treatment with an antipsychotic. The study did not discuss what the time interval should be between antipsychotic initiation and review; however, it does state that if there is a lack of improvement, the dose should be increased until side effects appear and continued for a period of 4 weeks.

Strengths and limitations

A Delphi method was chosen in this study as it is particularly appropriate when developing consensus when existing evidence is insufficient. Other methods of consensus development, such as nominal group technique, were not feasible as the experts participating in the consensus development worked in different geographical regions. Another strength of choosing the Delphi technique is that of quasi-anonymityCitation42 although the participants are known to the researcher, the participants remain anonymous to each other, preserving independent opinion. The multidisciplinary nature of the Delphi participants offered the opportunity to consider the different views of clinicians involved in the care of people with BPSD and enriched the results.

A limitation of this study is the small number of Delphi participants, with only 14 members. However, as little as ten members have been reported to yield strong evidence in Delphi studies.Citation56 Another limitation is the relatively high dropout rate of 21.4% after three members dropped out of the study in round 2. However, despite this dropout, the response rate remained above 70% for each round, which is the recommended response level to yield robust results.Citation57 We did not, therefore, follow-up with nonresponders. The choice of methodology prevented in-depth discussion among the expert participants; however, the ability to provide in-depth qualitative feedback allowed for the sharing of ideas. In addition, the existence of the research steering group facilitated in-depth discussion on selected topics as required. As the content for this eDelphi was quite clinical in nature, the decision was made to not include people living with dementia or their caregivers in the initial eDelphi process. However, an important next step would be to get the input of people living with dementia, their caregivers and nursing home staff prior to implementation of the monitoring tool in a clinical setting.

Implications for future research

The existence of a repeat prescribing tool for monitoring antipsychotic prescribing in general practice will not in itself guarantee that monitoring will occur. The feasibility and acceptability of the tool need to be evaluated in clinical practice. This phase will involve all relevant stakeholders including people with dementia, their caregivers, nursing home staff and community pharmacists.

This tool needs to be evaluated to identify whether implementation of the tool leads to more frequent reviews and more appropriate prescribing and de-prescribing of antipsychotics in people living with dementia. Future research then needs to focus on incorporating this antipsychotic repeat prescribing tool into a wider intervention that addresses all the barriers to conducting antipsychotic reviews in people with dementia in a general practice setting. These challenges can include a lack of knowledge on the part of some GPs of the adverse effects of antipsychotics in dementia and an overestimation of their benefits in BPSD.Citation58,Citation59 This can lead to a lack of motivation to monitor prescribing on the part of the GP – why monitor if you do not intend to stop the medication? In addition to highlighting the value of monitoring antipsychotics, GPs need to be further supported by practical advice on how to conduct an antipsychotic review and how to gradually taper antipsychotic medications. This repeat monitoring tool provides general prescribing guidance to GPs monitoring patients with dementia on an antipsychotic. However, patients will need to be assessed and managed at an individual level in accordance with their comorbidities and risk factors. The tool developed here is intended as an educational device as well as a practical tool. Further GP-relevant guidelines on antipsychotic prescribing would support GPs in conducting this task.Citation10

Conclusion

Through an expert consensus process, we developed a repeat prescribing tool for use by GPs when initiating and monitoring antipsychotic medications prescribed to people living with dementia in the community or in a nursing home setting. This tool provides GPs with practical advice that can be lacking in current guidelines and provides an additional level of detail to GPs to aid clinical decision-making. This tool will help to support GPs by providing a structured format to use when reviewing antipsychotic prescriptions in people with dementia, ultimately improving patient care.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as part of a larger research project – PREPARED (Primary Care Education, Pathways and Research of Dementia). PREPARED is supported by a 3-year grant (2015–2018) from Atlantic Philanthropies and the Health Service Executive, Ireland. TF is the principle investigator on the PREPARED project. The funders played no role in the design, execution, analysis or writing of the study.

Disclosure

AAJ received a PhD stipend as part of the grant awarded by Atlantic Philanthropies and the Health Service Executive (Ireland), and received 3-year career research grant from the Irish College of General Practitioners (2017–2020). The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SavvaGMZaccaiJMatthewsFEDavidsonJEMcKeithIBrayneCMedical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing StudyPrevalence, correlates and course of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in the populationBr J Psychiatry2009194321221919252147

- SteinbergMShaoHZandiPCache County InvestigatorsPoint and 5-year period prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County StudyInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200823217017717607801

- TootSSwinsonTDevineMChallisDOrrellMCauses of nursing home placement for older people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysisInt Psychogeriatr201729219520827806743

- WancataJWindhaberJKrautgartnerMAlexandrowiczRThe consequences of non-cognitive symptoms of dementia in medical hospital departmentsInt J Psychiatry Med200333325727115089007

- OrnsteinKGauglerJEThe problem with “problem behaviors”: a systematic review of the association between individual patient behavioral and psychological symptoms and caregiver depression and burden within the dementia patient-caregiver dyadInt Psychogeriatr201224101536155222612881

- PrinceMComas-HerraraAKnappMGuerchetMKaragianndouMReportWAImproving Healthcare for People Living with Dementia: Coverage, Quality and Costs Now and in the FutureLondon, UKAlzheimer’s Disease International201620162145

- DownsMGThe role of general practice and the primary care team in dementia diagnosis and managementInt J Geriatr Psychiatry19961111937942

- Wood-MitchellAJamesIAWaterworthASwannABallardCFactors influencing the prescribing of medications by old age psychiatrists for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: a qualitative studyAge Ageing200837554755218641003

- FoleyTBoyleSJenningsASmithsonWH“We’re certainly not in our comfort zone”: a qualitative study of GPs’ dementia-care educational needsBMC Fam Pract20171816628532475

- JenningsAAFoleyTMchughSBrowneJPBradleyCP‘Working away in that Grey Area…’ A qualitative exploration of the challenges general practitioners experience when managing behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementiaAge Ageing201847229530329220480

- GuidelinesNhomepage on the InternetDementia: Supporting People With Dementia and Their Carers in Health and Social Care2006 Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG42Accessed 27 February 2018

- TestadICorbettAAarslandDThe value of personalized psychosocial interventions to address behavioral and psychological symptoms in people with dementia living in care home settings: a systematic reviewInt Psychogeriatr20142671083109824565226

- AbrahaIRimlandJMTrottaFMSystematic review of systematic reviews of non-pharmacological interventions to treat behavioural disturbances in older patients with dementia. The SENATOR-OnTop seriesBMJ Open201773e012759

- MarstonLNazarethIPetersenIWaltersKOsbornDPPrescribing of antipsychotics in UK primary care: a cohort studyBMJ Open2014412e006135

- SchneiderLSDagermanKInselPSEfficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trialsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200614319121016505124

- MaustDTKimHMSeyfriedLSAntipsychotics, other psychotropics, and the risk of death in patients with dementia: number needed to harmJAMA Psychiatry201572543844525786075

- SchneiderLSTariotPNDagermanKSCATIE-AD Study GroupEffectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s diseaseN Engl J Med2006355151525153817035647

- WetzelsRBZuidemaSUde JongheJFVerheyFRKoopmansRTPrescribing pattern of psychotropic drugs in nursing home residents with dementiaInt Psychogeriatr20112381249125921682938

- WalshKAO’ReganNAByrneSBrowneJMeagherDJTimmonsSPatterns of psychotropic prescribing and polypharmacy in older hospitalized patients in Ireland: the influence of dementia on prescribingInt Psychogeriatr201628111807182027527842

- GallagherPCurtinDde SiúnAAntipsychotic prescription amongst hospitalized patients with dementiaQJM2016109958959326976947

- National Audit of Dementia care in general hospitals 2012–13Second round audit report and update Royal College of Psychiatrists2013 Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/NAD%20NATIONAL%20REPORT%202013%20reports%20page.pdfAccessed June 23, 2018

- WalshKADennehyRSinnottCInfluences on Decision-Making Regarding Antipsychotic Prescribing in Nursing Home Residents With Dementia: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative EvidenceJ Am Med Dir Assoc20171810897.e1897.e12

- JenningsAAFoleyTWalshKACoffeyABrowneJPBradleyCPGeneral practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes and experiences of managing behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: protocol of a mixed methods systematic review and meta-ethnographySyst Rev2018716229685175

- JenningsAAFoleyTWalshKACoffeyABrowneJPBradleyCPGeneral practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of managing behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: A mixedmethods systematic reviewInt J Geriatr Psychiatry201833911631176

- ChenYBriesacherBAFieldTSTjiaJLauDTGurwitzJHUnexplained variation across US nursing homes in antipsychotic prescribing ratesArch Intern Med20101701899520065204

- BarnesTRBanerjeeSCollinsNTreloarAMcintyreSMPatonCAntipsychotics in dementia: prevalence and quality of antipsychotic drug prescribing in UK mental health servicesBr J Psychiatry2012201322122622790679

- Thompson CoonJAbbottRRogersMInterventions to reduce inappropriate prescribing of antipsychotic medications in people with dementia resident in care homes: a systematic reviewJ Am Med Dir Assoc2014151070671825112229

- BallardCOrrellMYongzhongSImpact of Antipsychotic Review and Nonpharmacological Intervention on Antipsychotic Use, Neuropsychiatric Symptoms, and Mortality in People With Dementia Living in Nursing Homes: A Factorial Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial by the Well-Being and Health for People With Dementia (WHELD) ProgramAm J Psychiatry2016173325226226585409

- van der SpekKKoopmansRTCMSmalbruggeMThe effect of biannual medication reviews on the appropriateness of psychotropic drug use for neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia: a randomised controlled trialAge Ageing201847343043729432518

- HassonFKeeneySMckennaHResearch guidelines for the Delphi survey techniqueJ Adv Nurs20003241008101511095242

- JormAFUsing the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health researchAust N Z J Psychiatry2015491088789726296368

- BoulkedidRAbdoulHLoustauMSibonyOAlbertiCUsing and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic reviewPLoS One201166e2047621694759

- DonohoeHStellefsonMTennantBAdvantages and Limitations of the e-Delphi TechniqueAm J Health Educ20124313846

- LyonRSJReducing Antipsychotics in People Living with DementiaSussex Partnership NHS2015Version 53132

- GardnerDTMAntipsychotics Safety Monitoring Recommendation Record (Adults)2015 Available from: http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/frm-18658.pdfAccessed June 23, 2018

- South Staffordshire & Shropshire Healthcare NHS Foundation TrustAntipsychotics in Dementia2012 Available from: http://www.sssft.nhs.uk/images/pharmacy/documents/escas/SStaffs-Antipsychotics-in-Dementia-Guidelines-Version-3.pdfAccessed June 23, 2018

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [homepage on the Internet] Dementia – assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers2016 Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg42Accessed 14 June 2018

- ReusVIFochtmannLJEylerAEThe American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline on the Use of Antipsychotics to Treat Agitation or Psychosis in Patients With DementiaAm J Psychiatry2016173554354627133416

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO) Clinical Best Practice Guidlines: Delirium, Dementia, and Depression in Older Adults: Assessment and CareSecond Edition2016 Available from: http://rnao.ca/bpg/guidelines/assessment-and-care-older-adults-delirium-dementia-and-depressionAccessed June 23, 2018

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) Best Practice Guide: Antipsychotics in Dementia2016 Available from:https://bpac.org.nz/a4d/resources/docs/bpac_A4D_best_practice_guide.pdfAccessed June 23, 2018

- DyerSMLaverKPondCDCummingRGWhiteheadCCrottyMClinical practice guidelines and principles of care for people with dementia in AustraliaAust Fam Physician2016451288488927903038

- KeeneySHassonFMckennaHConsulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing researchJ Adv Nurs200653220521216422719

- BerkLJormAFKellyCMDoddSBerkMDevelopment of guidelines for caregivers of people with bipolar disorder: a Delphi expert consensus studyBipolar Disord2011135–655657022017224

- ZuidemaSUJohanssonASelbaekGA consensus guideline for antipsychotic drug use for dementia in care homes. Bridging the gap between scientific evidence and clinical practiceInt Psychogeriatr201527111849185926062126

- BondKSJormAFKitchenerBAKellyCMChalmersKJDevelopment of guidelines for family and non-professional helpers on assisting an older person who is developing cognitive impairment or has dementia: a Delphi expert consensus studyBMC Geriatr201616112927387756

- BakMFransenAJanssenJvan OsJDrukkerMAlmost all antipsychotics result in weight gain: a meta-analysisPLoS One201494e9411224763306

- Dementia: Assessment, Management and Support for People Living With Dementia and Their Carers2018 Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97Accessed 23 June 2018

- LavanAHGallagherPParsonsCO’MahonyDSTOPPFrail (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in Frail adults with limited life expectancy): consensus validationAge Ageing201746460060728119312

- PageAPotterKCliffordRMclachlanAEtherton-BeerCPrescribing for Australians living with dementia: study protocol using the Delphi techniqueBMJ Open201558e008048

- PageATPotterKCliffordRMclachlanAJEtherton-BeerCMedication appropriateness tool for co-morbid health conditions in dementia: consensus recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panelIntern Med J201646101189119727527376

- KrögerEWilcheskyMMarcotteMMedication Use Among Nursing Home Residents With Severe Dementia: Identifying Categories of Appropriateness and Elements of a Successful InterventionJ Am Med Dir Assoc2015167629.e1629.e17

- ParsonsCMccannLPassmorePHughesCDevelopment and application of medication appropriateness indicators for persons with advanced dementia: a feasibility studyDrugs Aging2015321677725480124

- FarrellBTsangCRaman-WilmsLIrvingHConklinJPottieKWhat are priorities for deprescribing for elderly patients? Capturing the voice of practitioners: a modified delphi processPLoS One2015104e012224625849568

- HolmesHMSachsGAShegaJWHoughamGWCox HayleyDDaleWIntegrating palliative medicine into the care of persons with advanced dementia: identifying appropriate medication useJ Am Geriatr Soc20085671306131118482301

- ZuidemaSUJohanssonASelbaekGA consensus guideline for antipsychotic drug use for dementia in care homes. Bridging the gap between scientific evidence and clinical practiceInt Psychogeriatr201527111849185926062126

- GregoryJSkulmoskiJKrahnJThe Delphi Method for Graduate ResearchJ Inf Technol Educ20076

- SumsionTThe Delphi Technique: An Adaptive Research ToolBritish Journal of Occupational Therapy1998614153156

- CousinsJMBereznickiLRCoolingNBPetersonGMPrescribing of psychotropic medication for nursing home residents with dementia: a general practitioner surveyClin Interv Aging2017121573157829042758

- DonyaiPIdentifying fallacious arguments in a qualitative study of antipsychotic prescribing in dementiaInt J Pharm Pract201725537938727896873