Abstract

Background

With no cure for dementia and the number of people living with the condition predicted to rapidly rise, there is an urgent need for dementia risk reduction and prevention interventions. Modifiable lifestyle risk factors have been identified as playing a major role in the development of dementia; hence, interventions addressing these risk factors represent a significant opportunity to reduce the number of people developing dementia. Relatively few interventions have been trialed in older participants with cognitive decline (secondary prevention).

Objectives

This study evaluates the efficacy and feasibility of a multidomain lifestyle risk reduction intervention for people with subjective cognitive decline (SCD) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Methods

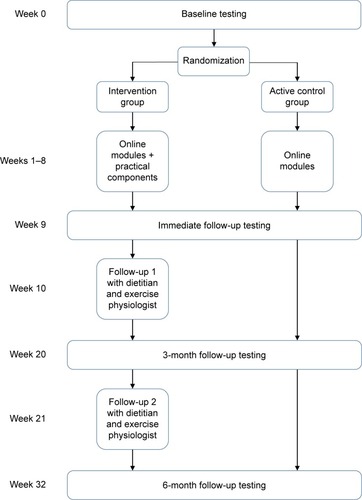

This study is an 8-week, two-arm, single-blind, randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a lifestyle modification program to reduce dementia risk. The active control group receives the following four online educational modules: dementia literacy and lifestyle risk, Mediterranean diet (MeDi), cognitive engagement and physical activity. The intervention group also completes the same educational modules but receives additional practical components including sessions with a dietitian, online brain training and sessions with an exercise physiologist to assist with lifestyle modification.

Results

Primary outcome measures are cognition (The Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive-Plus [ADAS-Cog-Plus]) and a composite lifestyle risk factor score for Alzheimer’s disease (Australian National University – Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Index [ANU-ADRI]). Secondary outcome measures are motivation to change lifestyle (Motivation to Change Lifestyle and Health Behaviour for Dementia Risk Reduction [MCLHB-DRR]) and health-related quality of life (36-item Short Form Health Survey [SF-36]). Feasibility will be determined through adherence to diet (Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener [MEDAS] and Australian Recommended Food Score [ARFS]), cognitive engagement (BrainHQ-derived statistics) and physical activity interventions (physical activity calendars). Outcomes are measured at baseline, immediately post-intervention and at 3- and 6-month follow-up by researchers blind to group allocation.

Discussion

If successful and feasible, secondary prevention lifestyle interventions could provide a targeted, cost-effective way to reduce the number of people with cognitive decline going on to develop Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias.

Introduction

The number of people with dementia is projected to rise to almost 75 million worldwide by 2030, and in the absence of a cure, there is an urgent need for strategies to reduce the number of people developing dementia.Citation1 It has been estimated that up to half of all Alzheimer’s disease (AD) cases worldwide may be attributed to seven modifiable risk factors, the majority of which reflect cardiovascular risks such as physical inactivity, hypertension, obesity, and diabetes.Citation2

Primary prevention of dementia aims to reduce risk factors by focusing on improving the lifestyle of middle-aged people prior to or in the very earliest stages of the neuropathological changes which characterize AD and other types of dementia.Citation3 An alternative strategy is secondary prevention, which aims to minimize any further damage or slow progression once symptoms of a disease begin to emerge. In the case of dementia, it is thought that the very earliest symptoms of disease are characterized by subjective cognitive decline (SCD) and later by mild cognitive impairment (MCI).Citation3 SCD is a condition in which people report cognitive deficits in day-to-day life, but these are not detectable with cognitive testing.Citation4 The cognitive deficits of people with MCI are detectable with cognitive testing, but do not reach the threshold to meet the criteria for dementia.Citation5 Both SCD and MCI are associated with increased risk of progressing to dementia,Citation5,Citation6 and the earliest stages of brain pathology found in dementia are also present in these conditions.Citation7–Citation10

Although dementia is not considered to be a reversible condition, there are some indications that in these prodromal stages the brain may still retain sufficient neuroplasticity that the trajectory of the disease may be modifiable. For instance, in individuals with MCI, conversion rates to AD are 7% at 1 year, 24% at 3 years and 59% at 6 years.Citation11,Citation12 Annually, approximately 25% of those with MCI revert back to normal cognitive status.Citation13 There are differing explanations for this pattern of changes in cognitive status such as differing definitions for MCI, differences in testing procedures and test and retest effects that do not adequately represent these participants’ true level of cognitive function. One explanation that cannot be discounted is that these low annual conversion rates and a high percentage of people reverting back to cognitively normal status suggest that this period may represent a “window of opportunity” for interventions to modify the disease course.

Three factors that have been identified by systematic reviews as having the potential to decrease lifestyle risk of dementia are diet, cognitive engagement, and physical activity.Citation14,Citation15

One dietary pattern that has shown promise in recent research is the Mediterranean diet (MeDi). The MeDi is a dietary pattern which is predominantly plant-based, with a high intake of vegetables, fruits, nuts and legumes, moderately high intake of fish, low intake of red meat, and includes extra virgin olive oil as the main source of fat.Citation16 The MeDi has been shown to decrease dementia risk indirectly through altering cardiovascular risk factors,Citation17 as well as directly through lower levels of neuropathology such as amyloid plaques,Citation18 brain atrophy,Citation19 and structural connectivity.Citation20

One of the most compelling studies in the area of cognitive engagement is the Advanced Cognitive Training in Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) trial.Citation21 The ACTIVE trial was a computerized cognitive training randomized controlled trial (RCT), comparing memory, reasoning, and speed of processing training conditions to a control condition. The speed of processing training group showed higher cognition and lower incident dementia at 10 years post-intervention, relative to the control group.Citation21,Citation22 Although the ACTIVE trial was conducted with a cognitively normal sample over the age of 65 years, these effects have yet to be replicated in a group with cognitive decline, such as SCD or MCI.

Similar to diet, physical activity is both indirectly and directly related to dementia risk. Physical activity has repeatedly been shown to be protective against cardiovascular risk factors for dementiaCitation23 and to reduce AD risk directly through a host of neuronal mechanisms, including downregulating pathways that lead to amyloid and tau production.Citation24 In a review of modifiable risk factors, physical inactivity has the highest attributable risk of the seven dementia risk factors identified (18% of all dementia cases in Australia).Citation25 Although the bulk of evidence for these factors comes from primary prevention studies (eg, with middle-aged adults), systematic reviews have highlighted the need to explore such approaches as secondary prevention interventions in people experiencing the earliest stages of cognitive decline.Citation26–Citation28

Some early studies in the area of secondary prevention have shown encouraging results. A 12-week, single-arm intervention for community-dwelling people with MCI (n=127, average age 70.7 years) involving MeDi, omega-3 supplements, physical activity, cognitive stimulation, neurofeedback, and meditation achieved positive results.Citation29 At the final follow-up, 84% of the participants showed statistically significant improvements in cognition and 53% of a subsample (n=17) that underwent neuroimaging showed hippocampal growth. Limitations of this study were that there was no control group and participants were not randomized, making it difficult to determine whether the effects were due to the intervention, and the low number of participants in the neuroimaging subsample means that these changes may not be representative of the whole sample. The study concluded that further multidomain RCTs should be conducted in participants experiencing cognitive decline. One multidomain RCT was conducted in community-dwelling frail and prefrail participants over the age of 65 years, which compared interventions for physical activity, cognitive activity, nutrition, and a combination of the three interventions against a control group.Citation30 Over 12 months, improvements in different domains of cognition were seen with all groups except the physical activity intervention group, in comparison to declines seen in the control group. As one of the limitations, the study noted that as physical frailty was the primary target of the intervention, only 7% of the sample had a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score less than 26 and the study may have been underpowered to detect all cognitive effects. The study recommended that further multidomain RCTs should be trialed in participants with greater levels of cognitive impairment as greater benefits may be possible with this population.

Although preliminary studies on secondary prevention do report positive outcomes, there is a need for more rigorous, multidomain studies such as RCTs, designed specifically to look at relevant outcomes such as cognition and lifestyle risk factors.

Objectives

The Body, Brain, Life (BBL) interventions are a suite of multidomain, primary dementia risk reduction interventions.Citation31–Citation33 The original intervention included educational modules only and more recently face-to-face physical activity and dietary components have been added.Citation32 The present study, Body, Brain, Life for Cognitive Decline (BBL-CD), draws from the earlier interventions but introduces some new components and adaptations so that it is suitable for participants with cognitive impairment. This study evaluates the feasibility and efficacy of adapting this program for a cognitively impaired population.

The specific aims of the study are to

evaluate the efficacy of BBL-CD in the prevention of further cognitive decline;

evaluate the efficacy of BBL-CD to reduce overall lifestyle risk of AD and other dementias and

evaluate the feasibility of BBL-CD through tracking intervention adherence.

Methods

Study design

The study is an 8-week, two-arm, parallel group RCT. The intervention focuses on the following three domains of lifestyle: diet, cognitive engagement, and physical activity. The active control group will undertake four online educational modules and the intervention group will undertake the same online modules complemented by practical and face-to-face sessions with interventionists. The study is expected to complete data collection in late 2018. This study is registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12617000792325) and ethical approval for conducting this study was granted by the Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol: 2016/360). The study has been planned and conducted in accordance with the revised Declaration of Helsinki,Citation34 and all participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study. This protocol was written to conform with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) checklist.Citation35

Participants

Participants are community-dwelling individuals with MCI or SCD recruited through advertisements in community newsletters, local print media, and radio. The inclusion criteria are as follows: living in the Australian Capital Territory or Queanbeyan, New South Wales; aged 65 years or over; owning a computer with Internet access; having sufficient English language skills; being prepared to make lifestyle changes to improve health; and having a medical diagnosis of MCI or meeting the Jessen criteriaCitation4 for SCD (clinically normal on objective assessment, self/informant-reported cognitive decline, decline not better accounted for by major medical and neurological or psychiatric diagnosis). The criteria for MCI are met if the participant has previously received a diagnosis of MCI from a suitably qualified medical professional such as a neuropsychologist or geriatrician (no exact criteria for MCI diagnosis are specified). The criteria for SCD are met if the participant expresses the view that they have experienced a decline in any domains of cognitive function in the past 5 years.

Exclusion criteria are as follows: currently participating in any lifestyle change interventions; have a diagnosis of AD or another form of dementia and have major psychiatric, neurological, or physical problems which would prevent them from taking part in a lifestyle change program.

All inclusion and exclusion criteria are assessed via an initial phone call to the research team when potential participants express interest in participating in the study. Participants meeting the criteria are sent an information sheet about the study and a consent form to sign and return.

If at any of the testing points cognitive testing is indicative of potential AD (The Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale [ADAS-Cog] >12), participants are referred to their general practitioner (GP) for cognitive testing. If found to have probable AD, the participant is withdrawn and no further data are collected; these participants are still allowed to continue participating in the practical components of the intervention, if they choose to (ie, participants will not be penalized or disadvantaged by a dementia diagnosis).

Randomization and stratification

After completing baseline data collection, participants are randomized in a 1:1 ratio, within strata defined by gender, baseline ADAS-Cog-Plus (above or below the median value of 7.0) and baseline ANU-ADRI (above or below the median value of 10.0), to intervention or control groups in permuted blocks of eight. The randomization sequence is generated from www.sealedenvelope.com by an independent researcher (RB).

Interventions

Active control

The active control group undertakes an 8-week, four-module, online educational course on dementia risk reduction and effective goal setting. The four modules are as follows:

Dementia literacy and lifestyle risk for AD (week 1): this module describes SCD, MCI, AD, and dementia, modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors and effective goal setting and rewards.

Diet (week 2): the diet module explains the importance of a healthy diet in maintaining a healthy brain. It explains the general principles of the MeDi and the scientific evidence that supports MeDi as a diet associated with lower levels of chronic disease and dementia.

Cognitive engagement (week 4): this module reviews the evidence for a cognitively engaged lifestyle being related to lower levels of dementia, different forms of cognitive engagement and how to increase cognitive engagement in everyday life.

Physical activity (week 6): this module discusses the evidence for an adequate level of physical activity in risk reduction of chronic disease and dementia. It also covers the importance of engaging in a combination of aerobic, strength, balance, and flexibility exercises and the Australian Department of Health’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for people ≥65 years.Citation36

The modules are interactive, including some questions to check participants’ understanding of the content, and give the opportunity to provide information about aspects of their lifestyle and ways in which they might be able to modify their behavior. Each module provides examples of how to set specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timed (SMART) goals for the particular domain. Each module takes approximately 1–2 hours to complete and can be completed across multiple sittings, if desired.

Intervention

The intervention group receives the same educational modules as the active control group, but each module is complemented by practical components to assist with the implementation of changes into the lifestyle in a sustainable way. The practical components are as follows:

Diet: to reinforce the content of the diet module, the participants have three face-to-face sessions with a dietitian, including an initial 1-hour session (week 3) and two further 30-minute follow-up sessions (weeks 10 and 21). In these sessions, the dietitian reviews the participant’s previous diet assessment results, discusses any barriers to adherence they are experiencing and ways in which the participant could achieve greater adherence to the MeDi. The MeDi intervention is adapted from the study by Estruch et al.Citation37 Recommendations are as follows: 1) ≥5 servings of vegetables/day, including two servings of raw vegetables; 2) ≥3 servings of fruit/day; 3) ≥3 serves of fish or seafood/week, including one serving of fatty fish; 4) ≥3 servings of legumes/week; 5) ≥3 servings of nuts/week; 6) preferentially consume white meat, instead of red meat; 7) <1 serving of red meat/day; 8) using olive oil as the main oil for cooking and dressing; 9) ≥4 servings of olive oil/day; 10) <1 serving of butter, margarine, or cream/day; 11) ≥7 servings of wine/week; 12) ≥2 servings of sofrito sauce/week (tomato, garlic, onion, and olive oil); 13) <1 serving of sweet or carbonated beverages/day; and 14) <3 servings of commercial sweets or pastries/week.

Cognitive engagement: to enable the participants to live a more cognitively engaged lifestyle, they are provided with a BrainHQCitation38 account (week 5) and asked to participate in two executive functions and two memory tasks for 30 minutes each (total 2 hours) per week. The four tasks are as follows: Double Decision (divided and selective attention, speed of processing, dual task, and useful field of view); Freeze Frame (visual phasic and tonic attention, inhibitory control and motor response inhibition); Syllable Stacks (auditory working memory); and Memory Grid (auditory spatial memory). The exercises are psychophysically adaptive and the parameters within each stimulus set are adjusted for an individual participant to maintain ~80% criterion accuracy by increasing or decreasing task difficulty systematically with correct/incorrect responses.

Physical activity: participants attend an initial 45-minute session (week 7) and two 30-minute follow-up sessions with an exercise physiologist (weeks 10 and 21). Based on the participant’s medical conditions, current level of exercise and physical activity preferences, a weekly exercise regime is developed with the eventual aim to increase physical activity level to 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week. If participants are already undertaking this level of exercise or greater, the goal is maintenance and combining different forms of exercises (eg, aerobic, strength, balance, and flexibility exercises). In the follow-up sessions, the exercise physiologist discusses progress, any barriers that the participant is experiencing and any modifications to the exercise regime, and (if suitable) increases toward 150 minutes total exercise duration. To be involved in these sessions, participants must have a medical clearance form signed by a GP, detailing any medical conditions or medications which may impact the participant’s ability to undertake exercise and approving the participant to undertake moderate physical exercise.

A week-by-week summary of the intervention is shown in .

Modifications made to previous BBL interventions

The BBL intervention has been modified each time it has been conducted, based on participant feedback on the previous version.Citation31–Citation33 Further modifications were made for this study to increase the suitability for an older population experiencing cognitive decline. The overall size and amount of information that participants are required to learn and remember in the online modules were decreased based on feedback from middle-aged participants that there was too much information to read and remember. Previous versions of BBL contained seven or eight informational modules on different dementia risk factors, followed by 4 weeks of revision. To enable a population experiencing cognitive deficits to effectively learn and modify their behavior without being overwhelmed, the content was reduced to three risk factors that could be most easily targeted to bring about effective risk reductions. Previous BBL studies involved one module on a new risk factor per week for the first 8 weeks. In BBL-CD, after a module on a risk factor is introduced, a week without a module is allotted for participants to implement these changes into their lifestyle. In BBL-CD, in week 8 at the conclusion of all the modules the participants have a week for revision and are sent a one-page summary of each module to convey the key messages of the intervention. Each module summary also provides an example of a SMART goal for that specific risk factor, so that participants can continue to modify their behavior beyond the initial 8-week intervention period. Specific modifications to the modules included the following: the diet module and practical intervention were modified from the previous BBL focusing on a healthy balanced diet to the MeDi in consultation with study dietitians; the brain training is a novel inclusion due to a change in the participant group to one experiencing cognitive decline; and the physical activity program is now focused on moderate physical activity, rather than a structured walking program based on feedback from participants who felt that the walking program was too restrictive. These modified modules and practical components were piloted with a small group of individuals (n=7) who volunteered to be participants but failed to meet a small number of the selection criteria (eg, less than 65 years of age, medical condition preventing dietary modification, etc). Feedback on each module and practical component was collected, and although overall feedback was positive, some modifications were implemented, eg, module wording changes and materials used during practical components.

Due to the high attrition rate in longitudinal intervention studies, several strategies to decrease attrition are being implemented. To make participants feel included and valued in the scientific process, newsletters are periodically sent about the progress of the study; participants are informed about any publications/conference presentations from the research; and participants are thanked after attending data collection and intervention sessions. The intervention group is termed the “Lifestyle Intervention Group” and the control group is termed the “Online Education Group”, such that participants in the control group do not feel they are receiving an intervention that is unlikely to have any effect.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

Cognition

Cognition is measured by the ADAS-Cog-Plus,Citation39 which contains the standard ADAS-Cog items (word recall, naming objects and fingers, following commands, constructional praxis, ideational praxis, orientation, word recognition, language production, language comprehension, and word finding difficulty)Citation40 with additional measures for executive function (trail making task,Citation41 symbol digit modalities test,Citation42 category fluency task,)Citation43 and instrumental activities of daily living (Pfeffer Functional Activities Questionnaire items 1, 2, 4, 7 and 9).Citation44 The inclusion of executive function and instrumental activities of daily living items is designed to maximize sensitivity to early-stage deficits as seen in SCD and MCI. The ADAS-Cog is scored from 0 to 70, with higher scores indicating greater levels of cognitive impairment. ADAS-Cog has good reliability (Cronbach’s α=0.83, test– retest=0.93)Citation45 and has been shown to discriminate between individuals with normal cognition, MCI and AD.Citation40 The inclusion of a full battery of cognitive measures is a new inclusion for the BBL studies, given a population experiencing cognitive decline.

Lifestyle risk of AD

Lifestyle risk factors for AD are measured by the Australian National University – Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Index (ANU-ADRI).Citation46 The ANU-ADRI covers 11 AD risk factors (eg, age, education and smoking) and four lifestyle factors that are protective against AD (eg, physical activity, fish intake, and cognitive activity). The ANU-ADRI applies an AD risk score for the level of each risk or protective factor, based on ORs derived from systematic reviews.Citation46 The ANU-ADRI yields a score ranging from -14 (highly protective lifestyle) to 73 (high-risk lifestyle). The ANU-ADRI has been validated against three large, international longitudinal cohort studies and was shown to be a valid predictor of development of AD.Citation47

Secondary outcome measures

Motivation

Motivation to change lifestyle is being assessed by the Motivation to Change Lifestyle and Health Behaviour for Dementia Risk Reduction (MCLHB-DRR).Citation48 This is a 27-item scale, which was developed based on the principles of the Health Belief Model. It was developed and validated specifically to look at motivation to change lifestyle in health and dementia lifestyle interventions.

Health-related quality of life

The 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)Citation49 is being used to assess general health-related quality of life. The SF-36 has 36-items which form an eight-scale profile of health-related quality of life which can be summarized into a physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS). An overall score of 0–100 can be calculated from the mean values of the eight scales. Higher scores indicate better health-related quality of life. The SF-36 is commonly used in health research, especially in the evaluation of interventions, as it is easily converted to quality of life years (QALYs), which gives a quantitative measure of the benefit of an intervention and can be used in a cost–benefit analysis.Citation50

Anthropometric measures

Height, weight, waist, and hip circumference are collected. Height to the nearest millimeter is measured using a stadiometer (Seca, Hamburg, Germany), and weight to the nearest 0.1 kg is measured with digital scales (Propert, Sydney, NSW, Australia).Citation51 Body mass index is calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Waist circumference is measured to the nearest centimeter midway between the lowest rib margin and the iliac crest.Citation51 Hip circumference is measured to the nearest centimeter at the point yielding the maximum circumference over the buttocks.Citation51

Feasibility and adherence measures

The feasibility of the lifestyle intervention for this participant group is measured through adherence to diet, cognitive engagement, and physical activity. Additional qualitative interviews with a subsample of participants will be undertaken at the conclusion of the study to investigate other factors affecting feasibility and adherence to interventions such as this.

Dietary assessment

Dietary adherence to the MeDi is assessed using a validated 14-point Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS).Citation52 A score of 0 or 1 is assigned to each item, with a maximum score of 14 indicating greatest adherence to the MeDi. The MEDAS has good convergent validity with a 137-item MeDi food frequency questionnaire and shows significant associations with health indices such as fasting glucose, total:high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ratio, triglycerides and coronary artery disease risk.Citation52

Dietary quality is assessed with a food-based diet quality index, the Australian Recommended Food Score (ARFS).Citation53 The ARFS is aligned with Australian Dietary GuidelinesCitation54 and the Australian Guide to Healthy EatingCitation55 recommendations. The ARFS total ranges from 0 to 73 and includes eight subscales: vegetables (0–21), fruit (0–12), protein (0–7), vegetarian protein alternatives (0–6), grains (0–13), dairy (0–11), water (0–1), and sauces and condiments (0–2). Higher scores indicate greater compliance with the Australian Dietary Guidelines and therefore better diet quality. The ARFS has demonstrated good validity and reproducibility.Citation53

Cognitive engagement

Duration of engagement with cognitive training and levels completed are tracked automatically via the BrainHQ website for the intervention group.

Physical activity

Participants track their daily physical activity on a paper-based physical activity calendar. The activity, intensity (on a 20-point scale),Citation56 and duration of the physical activity are recorded. Participants are asked to start completing this measure from the day of baseline testing onward and return these to the research team by electronic scan and email or by post at the end of every month.

Data collection

There are four primary data collection points in the study as follows: baseline (week 0); immediate post-intervention testing (week 9); 3-month testing (week 20); and 6-month testing (week 32). Research staff collecting data are blind to group allocation. Not all outcome measures are administered at each time point, and a summary of this is presented in .

Table 1 Summary of outcomes measured at data collection points

Statistical methods

Sample size calculation

The required sample size was determined to enable detection of a difference between groups at 6 months of 0.70 SDs for the primary outcomes. This equates to approximately 4.2 units for the ADAS-Cog-Plus and 4.0 units on the ANU-ADRI, both of which are clinically significant magnitudes. This requires a minimum of 72 participants (36 participants per arm) at the final follow-up period. Accounting for a potential attrition rate of 10% over four testing periods (60% remaining) yields a target sample size at baseline of 60 participants per group (120 in total).

Planned analyses

Linear mixed modeling to compare outcomes between intervention and control groups at each follow-up time, adjusted for baseline values of the outcome, will be conducted using complete cases as the primary analysis and full intention-to-treat analysis using multiple imputation to account for missing data as sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

There is a clear need for dementia prevention and risk reduction studies, given the anticipated rise in the number of people with dementia in the coming years.Citation1 Several authors have argued that secondary prevention (older populations showing some symptoms of cognitive decline) is an avenue that warrants further exploration.Citation26–Citation28 Drawing on epidemiological findings and previous trials and applying this to an older, high-risk group is the strategy that has been adopted for this study. Secondary prevention, if feasible and effective, provides a targeted approach to reducing the number of people developing dementia. Such intervention programs could be implemented through primary care providers who identify individuals in the high-risk SCD/MCI groups. Interventions could be run as collaborations between medical and allied health professionals and could be tailored to individuals’ specific needs based on their risk factor profile. Targeting a small number of people at very high risk of developing dementia would likely prove to be more cost-effective than targeting a larger number of people at lower risk.

The first step to showing the value of secondary prevention is to conduct randomized controlled studies to demonstrate feasibility and positive effects, such as reductions in risk factors or improvements in cognition in the SCD/MCI group. As a smaller, proof of concept study this research focuses on three of the most important risk factors: diet, cognitive engagement and physical exercise. This study aims to evaluate the efficacy of BBL-CD to prevent further cognitive decline and dementia risk profile and to evaluate the feasibility of the intervention for this participant group. These findings would provide proof of concept for a larger, longer secondary prevention trial with this group in the future.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this project is that all the components of the intervention have previously been used in separate successful interventions,Citation21,Citation31,Citation32,Citation37 but not with a group experiencing cognitive decline. The efficacy and feasibility of dementia risk reduction interventions in this group have been identified as a major knowledge gap by systematic reviews,Citation26–Citation28 and the use of multidomain interventions to combat multiple risk factors simultaneously is considered to be the “gold standard” for risk reduction and prevention interventions.Citation28

The greatest limitation of this research is the short follow-up time. Systematic reviews of RCTs in dementia risk reduction interventions recommend follow-up times of a year or longer.Citation27 Due to the paucity of research in the area of secondary prevention, it is important to first establish the feasibility of an adaptation of the BBL intervention to the SCD/MCI group and test the hypotheses that these individuals do appear to retain sufficient neuroplasticity to warrant a larger and longer trial.

Data sharing statement

Deidentified individual data sets are available indefinitely upon request to the authors following publication of the results of the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Richard Burns for his advice and assistance with the randomization of the sample. MM’s PhD Scholarship is supported by Dementia Australia Research Foundation, the Australian National University and Dementia Collaborative Research Centre. Additional research funding is provided by the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Cognitive Health, the Australian National University; Neuroscience Research Australia, University of New South Wales; the 2017 Royal Commonwealth Society Phyllis Montgomery Award; NHMRC Fellowship Funds (KA: APP1102694); and the Dementia Collaborative Research Centre (funds for precursor study). SK and LC are funded by the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Cognitive Health. None of the funding bodies played any part in the study conception, design, or conduct of the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Alzheimer’s Disease InternationalWorld Alzheimer’s Report 2015The Global Impact of Dementia. An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends2015

- BarnesDEYaffeKThe projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalenceLancet Neurol201110981982821775213

- FratiglioniLWinbladBvon StraussEPrevention of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Major findings from the Kungsholmen ProjectPhysiol Behav2007921–29810417588621

- JessenFAmariglioREvan BoxtelMA conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s diseaseAlzheimers Dement201410684485224798886

- PetersenRCMild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entityJ Intern Med2004256318319415324362

- MitchellAJBeaumontHFergusonDYadegarfarMStubbsBRisk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: meta-analysisActa Psychiatr Scand2014130643945125219393

- AmariglioREBeckerJACarmasinJSubjective cognitive complaints and amyloid burden in cognitively normal older individualsNeuropsychologia201250122880288622940426

- PikeKESavageGVillemagneVLBeta-amyloid imaging and memory in non-demented individuals: evidence for preclinical Alzheimer’s diseaseBrain2007130Pt 112837284417928318

- ShiFLiuBZhouYYuCJiangTHippocampal volume and asymmetry in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: meta-analyses of MRI studiesHippocampus200919111055106419309039

- PerrotinAde FloresRLambertonFHippocampal subfield volumetry and 3D surface mapping in subjective cognitive declineJ Alzheimers Dis201548s1S141S15026402076

- BradfieldNIEllisKASavageGBaseline amnestic severity predicts progression from amnestic mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease dementia at 3 yearsAlzheimer Dis Assoc Disord201832319019629561277

- WallinANordlundAJonssonMThe Gothenburg MCI study: design and distribution of Alzheimer’s disease and subcortical vascular disease diagnoses from baseline to 6-year follow-upJ Cereb Blood Flow Metab201636111413126174331

- Malek-AhmadiMReversion from mild cognitive impairment to normal cognition: a meta-analysisAlzheimer Dis Assoc Disord201630432433026908276

- XuWTanLWangHFMeta-analysis of modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201586121299130626294005

- BaumgartMSnyderHMCarrilloMCFazioSKimHJohnsHSummary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: a population-based perspectiveAlzheimers Dement201511671872626045020

- DavisCBryanJHodgsonJMurphyKDefinition of the Mediterranean diet; a literature reviewNutrients20157119139915326556369

- Salas-SalvadóJBecerra-TomásNGarcía-GavilánJFBullóMBarrubésLMediterranean diet and cardiovascular disease prevention: what do we know?Prog Cardiovasc Dis2018611626729678447

- BertiVWaltersMSterlingJMediterranean diet and 3-year Alzheimer brain biomarker changes in middle-aged adultsNeurology20189020e1789e179829653991

- LucianoMCorleyJCoxSRMediterranean-type diet and brain structural change from 73 to 76 years in a Scottish cohortNeurology201788544945528053008

- PelletierABarulCFéartCMediterranean diet and preserved brain structural connectivity in older subjectsAlzheimers Dement20151191023103126190494

- RebokGWBallKGueyLTTen-year effects of the ACTIVE cognitive training trial on cognition and everyday functioning in older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc20146211624417410

- EdwardsJDXuHClarkDRossLAUnverzagtFWThe ACTIVE study: what we have learned and what is next? Cognitive training reduces incident dementia across ten yearsAlzheimer’s Dementia2016127P212

- LanierJBBuryDCRichardsonSWDiet and Physical activity for cardiovascular disease preventionAm Fam Physician2016931191992427281836

- LoprinziPDFrithEPoncePMemorcise and Alzheimer’s diseasePhys Sportsmed201846214515429480042

- Ashby-MitchellKBurnsRShawJAnsteyKJProportion of dementia in Australia explained by common modifiable risk factorsAlzheimers Res Ther2017911128212674

- HorrTMessinger-RapportBPillaiJASystematic review of strengths and limitations of randomized controlled trials for non-pharmacological interventions in mild cognitive impairment: focus on Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Nutr Health Aging201519214115325651439

- SmartCMKarrJEAreshenkoffCNNon-pharmacologic interventions for older adults with subjective cognitive decline: systematic review, meta-analysis, and preliminary recommendationsNeuropsychol Rev201727324525728271346

- WilliamsJWPlassmanBLBurkeJHolsingerTBenjaminSPrevention Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive DeclineRockville, MDAgency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US)2010

- FotuhiMLubinskiBTrullingerMA Personalized 12-week “Brain Fitness Program” for improving cognitive function and increasing the volume of hippocampus in elderly with mild cognitive impairmentJ Prev Alzheimers Dis20163313313729205251

- LingNg TPFengALCognitive effects of multi-domain interventions among pre-frail and frail community-living older persons: randomized controlled trialJ Gerontol Series A2017

- AnsteyKJBahar-FuchsAHerathPBody brain life: a randomized controlled trial of an online dementia risk reduction intervention in middle-aged adults at risk of Alzheimer’s diseaseAlzheimers Dement2015117280

- KimSMcmasterMTorresSProtocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial of Body Brain Life-General Practice and a Lifestyle Modification Programme to decrease dementia risk exposure in a primary care settingBMJ Open201883e019329

- AnsteyKJKimShomepage on the InternetThe Body, Brain, Life-Fit (BBL-FIT) Program – A Pilot Study to Evaluate the Feasibility of the BBL-FIT Online Lifestyle Program in Middle-Aged Adults at Risk of Dementia (ACTRN12615000822583)Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry Available from: https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=3688972015Accessed October 24, 2018

- World Medical AssociationWorld Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjectsJAMA201331020219124141714

- ChanAWTetzlaffJMAltmanDGSPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trialsAnn Intern Med2013158320020723295957

- Australian Department of Health [homepage on the Internet]Physical Activity and Sendentary Behaviour Guidelines. Physical Activity and Sendentary Behaviour Guidelines Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/health-pubhlth-strateg-phys-act-guidelines#chbaAccessed 1/5/2018

- EstruchRRosESalas-SalvadóJPrimary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean dietN Engl J Med2013368141279129023432189

- Posit Sceince [homepage on the Internet]BrainHQ Available from: http://www.brainhq.comAccessed October 3, 2018

- SkinnerJCarvalhoJOPotterGGThe Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive-Plus (ADAS-Cog-Plus): an expansion of the ADAS-Cog to improve responsiveness in MCIBrain Imaging Behav20126448950122614326

- KueperJKSpeechleyMMontero-OdassoMThe Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog): modifications and responsiveness in pre-dementia populations. A narrative reviewJ Alzheimers Dis201863242344429660938

- ReitanRMTrail Making Test: Manual for Administration and ScoringTucson, AZReitan Neuropsychology Laboratory1992

- SmithASymbol Digit Modalities TestLos Angeles, CAWestern Psychological Services1982

- LucasJAIvnikRJSmithGEMayo’s older Americans normative studies: category fluency normsJ Clin Exp Neuropsychol19982021942009777473

- PfefferRIKurosakiTTHarrahCHChanceJMFilosSMeasurement of functional activities in older adults in the communityJ Gerontol19823733233297069156

- CanoSJPosnerHBMolineMLThe ADAS-cog in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials: psychometric evaluation of the sum and its partsJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201081121363136820881017

- AnsteyKJCherbuinNHerathPMDevelopment of a new method for assessing global risk of Alzheimer’s disease for use in population health approaches to preventionPrev Sci201314441142123319292

- AnsteyKJCherbuinNHerathPMA self-report risk index to predict occurrence of dementia in three independent cohorts of older adults: the ANU-ADRIPLoS One201491e8614124465922

- KimSSargent-CoxKCherbuinNAnsteyKJDevelopment of the motivation to change lifestyle and health behaviours for dementia risk reduction scaleDement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra20144217218325028583

- WareJESherbourneCDThe MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selectionMed Care19923064734831593914

- BrazierJRobertsJDeverillMThe estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36J Health Econ200221227129211939242

- GibsonRSPrinciples of Nutritional Assessment2nd edNew YorkOxford University Press2005

- SchröderHFitóMEstruchRA short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and womenJ Nutr201114161140114521508208

- CollinsCEBurrowsTLRolloMEThe comparative validity and reproducibility of a diet quality index for adults: the Australian Recommended Food ScoreNutrients20157278579825625814

- National Health and Medical Research CouncilAustralian Dietary Guidleines Available from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/n55Accessed on 10 May 20182013

- National Health and Medical Research CouncilAustralian Guide to Healthy EatingCanberraNational Health and Medical Research Council2003

- BorgGBorg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain ScalesChampaign, ILHuman kinetics1998