Abstract

Introduction

Many health care interventions have been developed that aim to improve or maintain the quality of life for frail elderly. A clear overview of these health care interventions for frail elderly and their effects on quality of life is missing.

Purpose

To provide a systematic overview of the effect of health care interventions on quality of life of frail elderly.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted in Embase, Medline (OvidSP), Cochrane Central, Cinahl, PsycInfo and Web of Science, up to and including November 2017. Studies describing health care interventions for frail elderly were included if the effect of the intervention on quality of life was described. The effects of the interventions on quality of life were described in an overview of the included studies.

Results

In total 4,853 potentially relevant articles were screened for relevance, of which 19 intervention studies met the inclusion criteria. The studies were very heterogeneous in the design: measurement of frailty, health care intervention and outcome measurement differ. Health care interventions described were: multidisciplinary treatment, exercise programs, testosterone gel, nurse home visits and acupuncture. Seven of the nineteen intervention studies, describing different health care interventions, reported a statistically significant effect on subdomains of quality of life, two studies reported a statistically significant effect of the intervention on the overall quality of life score. Ten studies reported no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups.

Conclusion

Reported effects of health care interventions on frail elderly persons’ quality of life are inconsistent, with most of the studies reporting no differences between the intervention and control groups. As the number of frail elderly persons in the population will continue to grow, it will be important to continue the search for effective health care interventions. Alignment of studies in design and outcome measurements is needed.

Introduction

The number of elderly people is expected to increase worldwide in the next decades. The number of persons aged 60 and above is expected to increase from 901 million in 2015 to 2.1 billion in 2050 and 3.2 billion in 2100. The number of persons aged 80 and above is expected to increase from 125 million in 2015 to 434 million in 2050 and 944 million in 2100.Citation1 Concurrently, the number of frail elderly will increase as well.

With the growing number of frail elderly, the concept of frailty has received more and more attention in recent years, and several definitions of frailty have been proposed.Citation2–Citation4 Many of these definitions are based on the theory that frailty is a multifactorial concept.Citation2–Citation6 These definitions are not only based on physical components, resulting in difficulties with activities of daily living (ADL), but also includes components referring to psychological and social functioning of older persons. One of the definitions which describe frailty as a multifactorial concept is the definition of Gobbens et al:

Frailty is a dynamic state affecting an individual who experiences losses in one or more domains of human functioning (physical, psychological, social), which is caused by the influence of a range of variables and which increases the risk of adverse outcomes.Citation3

The variables referred to in this definition are: socio-demographic factors (age, sex, marital status, ethnicity), socioeconomic factors (education, income), lifestyle, life events, environment and genetic factors.Citation3

The adverse outcomes of frailty are also diverse and present on different domains. Frailty is associated with increased risk of hip fractures, disability in ADL, hospitalization, institutionalization and mortality.Citation2,Citation7–Citation9 Also, several studies have shown that frail elderly experience lower quality of life than elderly with less frailty.Citation10–Citation13 Kojima et alCitation14 have shown in a systematic review that there is an inverse association between frailty/pre-frailty and quality of life among community-dwelling older people. Several studies also recommend conducting intervention studies to determine if quality of life in this frail population could be improved or maintained.Citation15,Citation16

Therefore, many health care interventions have been developed aiming to improve or maintain quality of life of frail elderly. These health care interventions are of a diverse nature, including all interventions with the aim to maintain or improve the health of the body and/or mind. Examples of these health care interventions are multidisciplinary interventions or physical exercise interventions. Nonetheless, a clear overview of these health care interventions for frail elderly and their effects on quality of life is missing. The objective of this review is therefore to provide a systematic overview of the effect of health care interventions on quality of life of frail elderly.

Material and methods

Study design

Systematized review according to the description of Grant et al.Citation17 This included a systematic research process. The presentation of the results is narrative with tabular accompaniment.Citation17 The review protocol was not registered.

Eligibility criteria

Type of studies: All clinical trials with a quantitative design.

Type of participants: Frail elderly identified with any frailty measurement instrument that assessed frailty on different domains.

Type of interventions: All types of health care interventions. These interventions were compared with a control intervention, either usual care or another intervention.

Type of outcome measurement: Quality of life.

Inclusion criteria were: 1) population of frail elderly; 2) measurement of frailty described in the study; 3) study about health care interventions; 4) study described the effect of the intervention on quality of life; 5) study designed as a randomized controlled trial, quasi-randomized controlled trial, controlled clinical trial or clinical trial; and 6) study was written in English, Dutch, German, or French.

Search strategy

Studies were identified by searching the Embase, Medline (OvidSP), Cochrane Central, Cinahl, PsycInfo and Web of Science databases from their inception up to and including November 2017. Keywords used were “frail elderly” (or frail* in a combination with eg, old or aged) and “quality of life” (or related terms such as QoL or HRQL). The complete search strategy for Embase and Medline (OvidSP) is presented in Supplementary material. This search strategy was adapted for the other databases. The adapted search strategies are available on request. The reference lists of all relevant reviews and potentially relevant studies were screened for additional studies. When relevant study designs or congress abstracts were found, the databases were searched for articles describing results of these studies more completely.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts of potentially relevant studies were screened by JvR or RW based on the inclusion criteria. Both authors independently read all full text articles reporting potentially relevant studies to make the final selection, using the same inclusion criteria. Disagreement was solved by discussion and consensus by the two reviewers. In case of persistent disagreement, a third reviewer could be consulted.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Risk of bias of the included studies was assessed using the “Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias”.Citation18 This list contains seven items: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. Each item was rated as low risk of bias, high risk of bias, or unclear. The methodological quality of the selected studies was independently assessed by two authors (JvR, RW). Disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus of the two reviewers. In case of persistent disagreement, a third reviewer could be consulted.

Data extraction and analysis

The following data were extracted from the included studies: study population (age, setting, number of participants), measurement of frailty, study characteristics (design, length of follow-up), type of intervention, control treatment and outcome: quality of life. If provided, the mean scores and SD for quality of life in the intervention and control groups were extracted. Given outcomes were extracted when mean scores and SD were not presented. One author (JvR or RW) performed the data extraction, which was checked by another author (JvR or RW). The authors of an included study were contacted if more information was required.

The outcomes of the included studies were described.

Results

Literature search

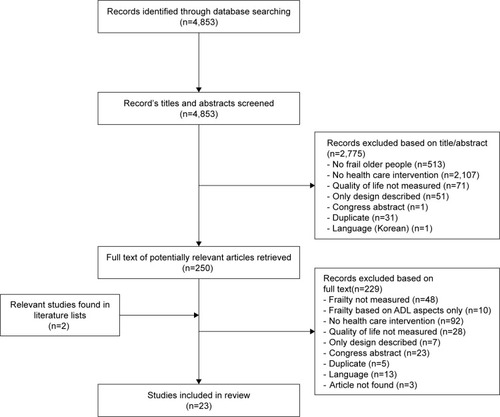

The literature search resulted in 4,853 potentially relevant articles (). After screening titles and abstracts, 250 potentially eligible articles were identified. Most of the articles excluded at this stage did not report about an intervention study (n=2,107) or the study population was not frail (n=513). This means that frailty either was not measured at all or was measured with an instrument that only assessed ADL. After reviewing the literature lists of potentially relevant studies, two studies were added for full text screening. Thus, in total 252 full text articles were evaluated. Twenty-three were included in this review. Most of the excluded articles reported a study that did not describe the results of a health care intervention (n=92), did not measure frailty (n=48), or did not measure quality of life (n=28). The 23 included articles described the results of 19 different interventions studies. Several articles described different follow-up periods from the same intervention study,Citation19–Citation24 and two articles described different aspects of the same intervention study.Citation25,Citation26

Methodological quality

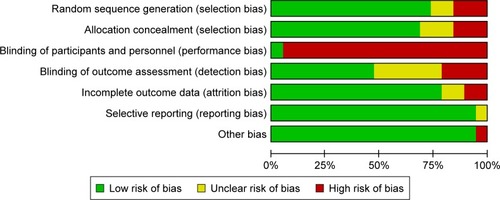

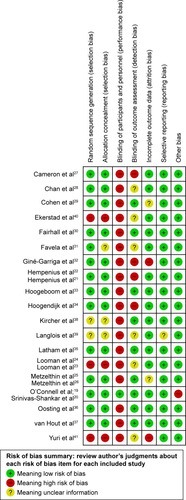

An overview of the methodological quality of the intervention studies is presented in .

Figure 2 Methodological quality of the included studies, using the Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias.

Fourteen of the nineteen included intervention studies used an adequate method for random sequence generation.Citation19–Citation22,Citation25–Citation37 Two of the nineteen studies provided insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgment of low or high risk.Citation38,Citation39 The only study in which participants, personnel as well as the outcome assessor, were blinded from knowledge of which intervention a participant received was the one described in the articles of O’Connell et alCitation19 and Srinivas-Shankar et al.Citation20 In this study, the use of a placebo testosterone gel served as control intervention. Eight other studies did blind the outcome assessor.25,26,29,30,33,35–38 In the study of Cameron et al,Citation27 outcome assessors were blinded, but many participants disclosed their treatment status to the outcome assessor. The risk of incomplete outcome data was unclear in two studies due to lack of information.Citation25,Citation26,Citation29 The risk of incomplete outcome data was high in the study of Giné-Garriga et alCitation32 and the study of Yuri et alCitation41 due to the high percentage and imbalance of loss to follow up, both in the control group and in the intervention group, and the lack of a sensitivity analysis. Other bias was high in the study of O’Connell et alCitation19 and Srinivas-Shankar et alCitation20 because they were sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry. shows the risk of bias summery, presenting the review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. This indicates that across the studies there is a high risk of performance bias because many studies did not blind the participants and/or the personnel.

Characteristics of the included studies

An overview of the characteristics and outcomes of the included studies is presented in . Populations and settings, frailty measurement instruments, quality of life measurements instruments and the types of intervention analyzed varied.

Table 1 An overview of the included studies, characteristics and outcomes

Population and settings

All studies had a minimum age limit, ranging from 60 to 75 years. Study participants were recruited from general practices,19,20,23–26,32,34,37 hospitals,Citation21,Citation22,Citation33,Citation36,Citation38,Citation40 rehabilitation centers,Citation27,Citation30,Citation35 veterans affairs medical centers,Citation29 neighborhood elderly centers,Citation28 health insurance database supplied by the Mexican Social Security Institute,Citation31 a certain city,Citation41 or unknown.Citation39

Frailty measurements

Different measurement instruments were used by the included studies to identify frail people. Validated instruments included the criteria of Fried which was used to identify frail people in two of the included studies,Citation19,Citation20 the Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI) was used in six of the included studies.Citation21–Citation26 Other validated measurement instruments which were used by the included studies were the Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI),Citation28 the Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale,Citation33 the criteria proposed by Lachs et al,Citation38 the Frail Elderly Support research group screening instrument,Citation40 the PRISMA-7,Citation34 the Kihon checklist,Citation41 and the frailty index “Identification of Seniors At Risk (ISAR)”.Citation36 The authors of other studies used newly developed frailty measurementsCitation29,Citation31,Citation35,Citation37 or combined existing frailty measurements with their own selection criteria.Citation32,Citation39

Quality of life instruments

The different instruments used to determine quality of life were: EuroQol (EQ)-5D,Citation23,Citation25–Citation27,Citation30,Citation34 EQ-6D,Citation24 Short Form (SF)-36.Citation21,Citation22,Citation29,Citation31,Citation35,Citation37 SF-12,Citation32,Citation34 RAND-36,Citation24 Aging Males’ Symptom scale,Citation19,Citation20 Hip Osteoarthritis Outcome Score,Citation33,Citation36 Quality of Life Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale (PGCMS),Citation38 the Quality of Life Systemic Inventory questionnaire,Citation39 the WHO Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF),Citation28 the Health Utilities Index-3 (HUI-3),Citation40 the Investigating Choice Experiments for CAPability measure for Older people (ICECAP)Citation24 and a 5-point Likert scale.Citation41

Type of interventions

Nine studies examined the effect of interventions based on a multidisciplinary treatment program with geriatric evaluation vs usual care.21–27,29,30,34,38,40 Five studies examined the effect of exercise programs vs usual care,Citation32,Citation33,Citation35,Citation36,Citation39 one study a combination of vitamin D and exercise vs a placebo tablet and social home visitsCitation35 and one study a preventive care program which included physical exercise classes, oral care and nutrition education.Citation41 Other interventions described were testosterone gel vs placebo,Citation19,Citation20 acupuncture intervention vs waiting listCitation28 and nurse home visits with or without alert buttons vs usual care.Citation31,Citation37

Effect of health care intervention on quality of life among frail elderly

Findings on the effect of the health care intervention on quality of life are also presented in . Based on the similarity of the intervention and the number of studies describing the intervention, the results of the included studies will be described in three subgroups: multidisciplinary treatment, exercise programs and other intervention.

Multidisciplinary treatment program with geriatric evaluation

Five of the nine studies which examined the effect of a multidisciplinary treatment program with geriatric evaluation reported no statistically significant differences concerning quality of life between the intervention and control groups.Citation25–Citation27,Citation30,Citation34,Citation38 Hempenius et alCitation21 reported no significant differences between groups at three months after discharge and no significant differences between groups for most SF-36 subscales at discharge, except for the SF-36 subscale bodily pain (OR 0.49, 95% CI: 0.29–0.82).Citation22 Looman et alCitation23 reported a statistically significant difference between groups in the attachment dimension of the ICECAP after 3 and 12 months follow-up: frail elderly in the control group perceived receiving lesser amounts of love and friendship than desired, whereas the intervention group was stable on this dimension.Citation23,Citation24 Cohen et alCitation29 reported statistically significant differences between groups in different dimensions of the SF-36 by comparing the mean change in scores at different time points, for example at baseline and discharge, of the intervention and control groups. In their study, inpatient geriatric care had a positive effect on the following domains at discharge: physical function (mean change in score of the intervention group: -1.5, mean change in score of the control group: -5.4, P=0.006), bodily pain (P=0.001), energy (P=0.01), and general health (P=0.006). The effect on the domain bodily pain was still present after one-year follow-up (P=0.01). The outpatient geriatric care had a positive effect on: energy (P=0.009), mental health (P=0.001), and general health (P=0.01). When mean changes of scores of the intervention and control group between discharge and 1-year follow-up were compared, only the improvement in the score for the mental health dimension remained significant (P=0.004). Ekerstad et alCitation40 reported a statistically significant difference between groups for four of the eight dimensions of the HUI-3 questionnaire (speech, ambulation, cognition and pain).

Exercise programs

Three of the six studies which examined the effect of an exercise program on quality of life reported no statistically significant difference between groups.Citation33,Citation35,Citation36 Giné-Garriga et alCitation32 reported a statistically significant difference between groups concerning the physical composite score (PCS) and the mental composite score (MCS) on the SF-12, after 12 and 36 weeks. After 12 weeks the average score of the PCS of the intervention group and the control group was 35.59 (SD 4.41) and 29.80 (SD 3.74) (P<0.001) respectively. Langlois et alCitation39 reported a statistically significant difference in favor of the intervention group in several domains of the Quality of Life Systemic Inventory questionnaire: global quality of life, leisure activities, perception of physical capacity, social/family relationships, and perceived physical health. Yuri et alCitation41 reported a statistically significant improvement in the quality of life measured with a five point Likert scale.

Other interventions: testosterone gel, nurse home visits with alert buttons or acupuncture

The study describing a testosterone gel intervention vs placebo gel reported a statistically significant difference on the somatic subscale 6 months after treatment (P=0.04),Citation20 which was not sustained 12 months after treatment (P=0.08).Citation19,Citation20 Favela et alCitation31 examined the effect of 1) weekly nurse home visits in combination with alert buttons and 2) only nurse home visits, and reported that none of the interventions had a statistically significant effect on quality of life. Likewise, van Hout et alCitation37 reported no statistically significant effect of nurse home visits on quality of life. Chan et alCitation28 reported statistically significant improvement on several domains of the WHOQOL-BREF after an acupressure intervention.

Discussion

This systematized review provides an overview of the effects of different health care interventions for frail elderly on quality of life. The reported effects seem low, but the findings were inconsistent and the study designs were very heterogeneous in the design. Ten intervention studies reported no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups. Seven studies reported a statistically significant effect on subdomains of quality of life and two studies reported a statistically significant effect of the intervention on the overall quality of life score.

Two previous reviews have focused in particular on the effect of exercise interventions for frail elderly.Citation42,Citation43 One of these, the systematic review by Chou et al,Citation42 concluded that exercise interventions had no effect on quality of life, but the results of the meta-analyses suggest that exercise increased gait speed, improved balance, and improved ADL performance of frail elderly.Citation42 The other, a review by Theou et al,Citation43 reported that exercise improved quality of life in four of the ten studies. The conclusions of these two reviews correspond with our results, namely inconclusive results concerning the effect of exercise interventions on frail elderly’s quality of life.

Several possible explanations for the lack of evidence of the effectiveness of the health care interventions have been proposed by the authors of several studies included in this review. First, the intervention and control treatments might not be very different. As health professionals will already be aware of the risks involved in treating frail elderly patients,Citation22 usual care often had many matching elements to the geriatric evaluation and management (GEM) intervention program and other multidisciplinary interventions. Therefore, the effectiveness of these interventions appeared to be limited.Citation22,Citation24–Citation26,Citation29,Citation38 Second, inadequate implementation of an intervention will affect research results.Citation25,Citation26,Citation37,Citation38 Several articles on the Dutch National Care Program for ElderlyCitation44–Citation46 indicated that the efficacy of a multidisciplinary intervention aimed at frail older people depended on adequate implementation of the intervention. Inadequate implementation occurred when eg, only part of the protocol was followed, application of the full protocol was perceived as time consuming, the protocol was perceived as difficult or because health care professionals requiring more training to apply the protocol.Citation25,Citation37,Citation38,Citation47,Citation48 During process evaluation of the multidisciplinary treatment program of Metzelthin et al,Citation25 professionals did report that they did not always follow the whole protocol due to time constraints or its complexity. Adequate implementation of the protocol is not only dependent on the professional, but also on the frail elderly. If a protocol is time-consuming or difficult to perform for the elderly, inadequate implementation or loss to follow-up may be the result. Third, group size might be decisive for a study’s results; two studies were pilot, randomized controlled trials with few participants.Citation33,Citation36 A similar trial with adequate sample sizes might result in different findings.

A major limitation of the present review was the heterogeneity of the included studies. The studies used different frailty measurements, different health care interventions and different outcome measurements for quality of life, which made it difficult to compare the results and to draw conclusions.

Furthermore, we focused only on the outcome quality of life. We did not describe adverse effects of the intervention. For that matter, most of the studies did not describe adverse effects. The testosterone gel intervention, however, is controversial. It is unclear if short-term testosterone treatment leads to long-term effects and there are concerns about its possible adverse effects, such as increased PSA and prostate cancer progression, as stated in the editorial comment on one of the articles.Citation49 Furthermore, high intensity resistance exercise might lead to musculoskeletal injury. In the study of Latham et al,Citation35 eighteen people (15%) in the exercise group had musculoskeletal injuries compared with five (4%) in the control group (RR 3.6, 95% CI 1.5–8.0). The other studies did not describe any adverse effects. The strength of this review is that this study included all health care interventions, which resulted in an overview of all assessed health care interventions and their results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this review found conflicting and inconsistent results concerning the effects of health care interventions for frail elderly on quality of life. Most of the included studies, however, reported no differences between intervention and control groups. As the population of older people will continue to grow, it will be important to pursue the search for effective health care interventions, not only regarding quality of life, but also other outcomes. Different aspects should be taken into consideration in order to make progression and improve quality of life among frail elderly in daily practice. It might be needed to adjust interventions enhancing the quality of the interventions and increasing the difference between the intervention and usual care. It is important to assure proper implementation of an intervention. It might be needed to adjust outcome measurements.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary material

Embase and Medline (OvidSP) search strategies

Embase (Embase and Medline)

(‘frail elderly’/de OR ((frail* AND (elder* OR old* OR aged OR geriatr* OR octogenar*)) OR (impair* NEXT/1 elder*)):ab,ti) AND (‘quality of life’/exp OR ((qualit* NEAR/3 (life OR liv*)) OR QOL OR HRQL):ab,ti)

Medline (OvidSP)

(“Frail Elderly”/OR ((frail* AND (elder* OR old* OR aged OR geriatr* OR octogenar*)) OR (impair* ADJ elder*)). ab,ti.) AND (“Quality of Life”/OR ((qualit* ADJ3 (life OR liv*)) OR QOL OR HRQL).ab,ti.)

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- United Nations DoEaSA, Population DivisionWorld Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, Key Findings & Advace TablesNew YorkUnited Nations2015

- LpFTangenCMWalstonJFrailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotypeJ Gerontol2001563146156

- GobbensRJLuijkxKGWijnen-SponseleeMTScholsJMTowards an integral conceptual model of frailtyJ Nutr Health Aging201014317518120191249

- Rodríguez-MañasLFéartCMannGSearching for an operational definition of frailty: a Delphi method based consensus statement. The frailty operative Definition-Consensus conference projectJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2013681626722511289

- de VriesNMStaalJBvan RavensbergCDHobbelenJSOlde RikkertMGNijhuis-van der SandenMWOutcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic reviewAgeing Res Rev201110110411420850567

- RockwoodKStadnykKMacknightCMcdowellIHébertRHoganDBA brief clinical instrument to classify frailty in elderly peopleThe Lancet19993539148205206

- Fugate WoodsNLacroixAZGraySLFrailty: emergence and consequences in women aged 65 and older in the women’s health Initiative Observational studyJ Am Geriatr Soc20055381321133016078957

- GobbensRJvan AssenMAFrailty and its prediction of disability and health care utilization: the added value of interviews and physical measures following a self-report questionnaireArch Gerontol Geriatr201255236937922595766

- RockwoodKSongXMacknightCA global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly peopleCMAJ2005173548949516129869

- BilottaCBowlingACasèADimensions and correlates of quality of life according to frailty status: a cross-sectional study on community-dwelling older adults referred to an outpatient geriatric service in ItalyHealth Qual Life Outcome2010815665

- LinCCCiLChangCKReduces health-related quality of life in elders with frailty: a cross-sectional study of community-dwelling elders in TaiwanPLoS One Journal20116717

- MaselMCGrahamJEReistetterTAMarkidesKSOttenbacherKJFrailty and health related quality of life in older Mexican AmericansHealth Qual Life Outcome2009770

- KanwarASinghMLennonRGhantaKMcnallanSMRogerVLFrailty and health-related quality of life among residents of long-term care facilitiesJ Aging Health201325579280223801154

- KojimaGIliffeSJivrajSWaltersKAssociation between frailty and quality of life among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Epidemiol Community Health201670771672126783304

- ChangY-WChenW-LLinF-GFrailty and its impact on health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study on elder community-dwelling preventive health service usersPLoS One201275e3807922662268

- GobbensRJvan AssenMALuijkxKGScholsJMThe predictive validity of the Tilburg frailty indicator: disability, health care utilization, and quality of life in a population at riskThe Gerontologist201252561963122217462

- GrantMJBoothAA typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologiesHealth Inform Lib J200926291108

- HigginsJPTAltmanDGGotzschePCThe Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trialsBMJ20113432d592822008217

- O’ConnellMDRobertsSASrinivas-ShankarUDo the effects of testosterone on muscle strength, physical function, body composition, and quality of life persist six months after treatment in intermediate-frail and frail elderly men?J Clin Endocrinol Metab201196245445821084399

- Srinivas-ShankarURobertsSAConnollyMJEffects of testosterone on muscle strength, physical function, body composition, and quality of life in intermediate-frail and frail elderly men: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJ Clin Endocrinol Metab201095263965020061435

- HempeniusLSlaetsJPJvan AsseltDde BockTHWiggersTvan LeeuwenBLLong term outcomes of a geriatric liaison intervention in frail elderly cancer patientsPLoS One2016112e014336426901417

- HempeniusLSlaetsJPJvan AsseltDde BockGHWiggersTvan LeeuwenBLOutcomes of a geriatric liaison intervention to prevent the development of postoperative delirium in frail elderly cancer patients: report on a multicentre, randomized, controlled trialPLoS One201386e6483423840308

- LoomanWMFabbricottiINde KuyperRHuijsmanRThe effects of a PRO-active integrated care intervention for frail community-dwelling older people: a quasi-experimental study with the GP-practice as single entry pointBMC Geriatr20161614326879893

- LoomanWMFabbricottiINHuijsmanRThe short-term effects of an integrated care model for the frail elderly on health, quality of life, health care use and satisfaction with careInt J Integr Care2014144e03425489294

- MetzelthinSFRossumEWitteLPFrail elderly people living at home; effects of an interdisciplinary primary care programme. [Dutch]Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde201415817A7355

- MetzelthinSFvan RossumEHendriksMRReducing disability in community-dwelling frail older people: cost-effectiveness study alongside a cluster randomised controlled trialAge Ageing201544339039625566783

- CameronIDFairhallNLangronCA multifactorial interdisciplinary intervention reduces frailty in older people: randomized trialBMC Med20131116523497404

- ChanCWCChauPHLeungAYMAcupressure for frail older people in community dwellings – a randomised controlled trialAge Ageing201746695796428472415

- CohenHJFeussnerJRWeinbergerMA controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and managementN Engl J Med20023461290591211907291

- FairhallNSherringtonCKurrleSEEconomic evaluation of a multifactorial, interdisciplinary intervention versus usual care to reduce frailty in frail older peopleJ Am Med Dir Assoc2015161414825239014

- FavelaJLaCFranco-MarinaFNurse home visits with or without alert buttons versus usual care in the frail elderly: a randomized controlled trialClin Interventions Aging201388595

- Giné-GarrigaMGuerraMUnnithanVBThe effect of functional circuit training on self-reported fear of falling and health status in a group of physically frail older individuals: a randomized controlled trialAging Clin Exp Res201325332933623740589

- HoogeboomTJDronkersJJvan den EndeCHMOostingEvan MeeterenNLUPreoperative therapeutic exercise in frail elderly scheduled for total hip replacement: a randomized pilot trialClin Rehabil2010241090191020554640

- HoogendijkEOvan der HorstHEvan de VenPMEffectiveness of a geriatric care model for frail older adults in primary care: results from a stepped wedge cluster randomized trialEur J Intern Med201628435126597341

- LathamNKAndersonCSLeeAA randomized, controlled trial of quadriceps resistance exercise and vitamin D in frail older people: the frailty Interventions Trial in elderly subjects (fitness)J Am Geriatr Soc200351329129912588571

- OostingEJansMPDronkersJJPreoperative home-based physical therapy versus usual care to improve functional health of frail older adults scheduled for elective total hip arthroplasty: a pilot randomized controlled trialArch Phys Med Rehabil201293461061622365481

- van HoutHPJJansenAPDvan MarwijkHWJPrevention of adverse health trajectories in a vulnerable elderly population through nurse home visits: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN05358495]J Gerontol A: Biol Sci Med Sci201065A7734742

- KircherTTJWormstallHMullerPHA randomised trial of a geriatric evaluation and management consultation services in frail hospitalised patientsAge and Ageing2007361364217264136

- LangloisFVuTTMChasseKDupuisGKergoatM-JBhererLBenefits of physical exercise training on cognition and quality of life in frail older adultsJ Gerontol B: Psychol Sci Soc Sci201368340040422929394

- EkerstadNDahlin-IvanoffSLandahlSIs the acute care of frail elderly patients in a comprehensive geriatric assessment unit superior to conventional acute medical care?Clin Interv Aging2017121239124928848332

- YuriYTakabatakeSNishikawaTOkaMFujiwaraTThe effects of a life goal-setting technique in a preventive care program for frail community-dwelling older people: a cluster nonrandomized controlled trialBMC Geriatrics201616111126729190

- ChouC-HHwangC-LWuY-TYtWEffect of exercise on physical function, daily living activities, and quality of life in the frail older adults: a meta-analysisArch Phys Med Rehabil201293223724422289232

- TheouOStathokostasLRolandKPThe effectiveness of exercise interventions for the management of frailty: a systematic reviewJ Aging Res201120113119

- FabbricottiINJanseBLoomanWMde KuijperRvan WijngaardenJDHReiffersAIntegrated care for frail elderly compared to usual care: a study protocol of a quasi-experiment on the effects on the frail elderly, their caregivers, health professionals and health care costsBMC Geriatrics20131313123586895

- BuurmanBMParlevlietJLAlloreHGComprehensive geriatric assessment and transitional care in acutely hospitalized patients: the transitional care bridge randomized clinical trialJAMA Intern Med2016176330230926882111

- Asmus-SzepesiKJEde VreedePLNieboerAPEvaluation design of a reactivation care program to prevent functional loss in hospitalised elderly: a cohort study including a randomised controlled trialBMC Geriatrics20111113621812988

- de VosACrammJMvan WijngaardenJDHBakkerTJEMMackenbachJPNieboerAPUnderstanding implementation of comprehensive geriatric care programs: a multiple perspective approach is preferredInt J Health Plann Manag2017324608636

- van HaastregtJCMDiederiksJPMvan RossumEDwlPCreboldeHEffects of preventive home visits to elderly people living in the community: systematic reviewBMJ2000320723775475810720360

- GrieblingTLRe: do the effects of testosterone on muscle strength, physical function, body composition, and quality of life persist six months after treatment in intermediate-frail and frail elderly men?J Urol2012187262222237359