Abstract

Background

Despite the aging of numerous societies and future health care challenges, clinical research in the elderly is underrepresented. The aim of this review was to analyze the current practice exemplary in gerontotraumatology and to discuss potential improvements.

Materials and methods

A literature review was performed in 2016 based on a PubMed search for gerontotraumatologic studies published between 2005 and 2015. Trials were evaluated for methodology and ethical and age-related aspects.

Results

The search revealed 649 articles, 183 of which met the inclusion criteria. The age range for inclusion was heterogeneous; one-third of trials included patients <65 years and only 11% excluded very elderly. Seventy-four trials excluded patients with typical comorbidities, with 55% of these without stating scientific reasons. Frailty was assessed in 94 trials and defined as the exclusion criterion in 66 of them. Informed consent (IC) was reportedly obtained in 144 trials; descriptions of the IC process mostly remained vague. Substitute decision making was described in 19 trials; the consenting party remained unclear in 45 articles. Diagnosed dementia was a primary exclusion criterion in 31% of the trials. Seventeen trials assessed decisional capacity before inclusion, with six using specific assessments.

Conclusion

Many trials in gerontotraumatology exclude relevant subgroups of patients, and thus risk presenting biased estimates of the relevant treatment effects. Exclusion based on age, cognitive impairment, or other exhaustive exclusion criteria impedes specific scientific progress in the treatment of elderly patients. Meaningful trials could profit from a staged, transparent approach that fosters shared decision making. Rethinking current policies is indispensable to improve treatment and care of elderly trauma patients and to protect study participants and researchers alike.

Introduction

Despite rising patient numbers, clinical research in elderly patients is underrepresented;Citation1–Citation6 some important treatment approaches have even not been evaluated at all in the elderly.Citation4,Citation5,Citation7 Reaching high-level evidence by means of clinical studies is challenging in surgery in general,Citation8,Citation9 and when elderly patients are involved, the obstacles seem potentiated, especially with respect to obtaining legitimate informed consent (IC).

Historical background

The current attitude toward research in humans is based on relatively new developments. Following the Hippocratic tradition and Percival’s Medical Ethics, deliberate nondisclosure has long been practiced.Citation10–Citation13 For medical treatment, the imperative for consent was only determined in the 20th century (“every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body”).Citation14

The “Berlin Codex” of 1901,Citation15 by contrast, is the first legally binding document that enforces consent for research; in addition, it specifically prohibits research in vulnerable populations and defines responsibilities for the compliance with these requirements. This governmental directive was issued as reaction to a research project in which prostitutes were unknowingly treated against syphilis with serum from recovering syphilis patients. The result was an epidemic of syphilis among the prostitutes and, most probably, their clients.

The doctrine of IC per se was formulated in the late 1940s in the Nuremberg CodeCitation16,Citation17 as reaction to the atrocities in the name of scientific progress during the Nazi regime. The Nuremberg Code roughly outlined the basic principles of research ethics that were established in more detail for the Declaration of Helsinki (DoH) of 1964.Citation18 Unlike the Berlin Codex, however, these guidelines had no legal status, thus rendering the prevention or ban of questionable practice difficult. BeecherCitation19 and PappworthCitation20 have both published reports about – from our present perspective – unbelievable cases of scientific misconduct in US health care institutions. Some of the studies were even approved by the regulatory authorities, as, for instance, the Tuskegee experiment: in this long-term observational study that was started in 1932, approximately 400 men suffering from syphilis were not adequately treated (even after the benefit of penicillin had been broadly accepted), in order to evaluate the natural course of the disease. Even in a re-evaluation in 1969, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reaffirmed the need for a continuation of the study. The study was only stopped 2 years later after a public outcry.Citation21 This incident led to the implementation of the National Research Act in 1974,Citation22 and consequently, the Belmont ReportCitation23 that defines the following three basic ethical principles to guide research practice:

Respect for persons

Beneficence

Justice.

This development and the implementation of institutional review boards and competent ethics committees coincided with the establishment of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelinesCitation24 that were embedded both in the Code of Federal Regulations in 1980Citation25 and the European legislation.Citation26

Not until ~40 years, laws give specific guidance on research with competent adults. The inclusion of patients with restricted cognitive or age-related capacity, however, is heavily regulated on the one hand, but remains vague considering details and definitions as was shown for nine European countries.Citation27 In geriatric populations, the percentage of patients suffering from cognitive impairment and decisional incapacity is high, and current regulations only poorly reflect the oftentimes fluent transition from competence to incompetence that is typically encountered in daily practice.Citation28–Citation31

Competence and capacity

Competence (as a legal term) and capacity (as functional description) are integral aspects of IC that, in turn, is an implicit part of one’s personality until proven otherwise. Accordingly, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization clarifies “… proof of incapacity is required, not proof of capacity. Foolish decisions can be voluntarily made by the most autonomous people and the freedom to do so should not be restricted by imposing over-stringent standards of capacity … .”Citation32 Also, current expert panels support this attitude of accepting seemingly unwise decisions without principally questioning capacity as a consequence,Citation5 which is regularly the case in daily clinical practice from our experience.

Recognizing evidence of incapacity or incompetence is dependent on the observers’ advertence, vulnerability to bias, education, and experiences on the one hand, and on the degree of impairment and the patients’ ability/interest to dissimulate on the other hand. Neurological or psychiatric comorbidities aggravate the impression of incompetence.Citation33 In this context, it is also important to note that evidence of cognitive impairment does not necessarily imply incompetence. Capability and, in consequence, competence is task specific, and thus dependent on the complexity of the task in proportion to the degree of impairment.

Scores in neuropsychological tests such as the Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) tend to correlate with the probability of incompetence.Citation33–Citation36 However, they only provide circumstantial evidence, which limits their usefulness as legal basis. Other tests have been specifically designed to assess four dimensions of competence:Citation37

Understanding (intake and procession of information)

Appreciation (evaluation of information in the individual context)

Reasoning (comparison of alternatives and realization of consequences)

Choice (deciding on one option and communication of the choice).

However, adequate application of these tests requires exercise and education, as they are prone to a high interob-server variability; furthermore, they tend to be time consuming, which restricts their use in clinical routine.

There are several difficulties in research with elderly patients. One of these is the definition of “elderly”. While the term “octogenarians” is specific, the terms “geriatric” and “elderly” are used at random. Some refer to individuals older than 60 years as geriatric, which would probably very much displease them; the WHO states “old is an individual-, culture-, country- and gender-specific term”Citation38 without further clarification. Another approach defines the geriatric patient either by typical multimorbidity and old age (usually ≥70) or solely by an age ≥80 due to an age-typical “vulnerability for complications, long-term sequelae, chronicity, and loss of autonomy”.Citation39

We use the term elderly for the population ≥65 years and geriatric for the population ≥65 with a component of frailty due to relevant comorbidity. The European Forum for Good Clinical Practice and the GCP guideline E7 issued by the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH-GCP) E7 give similar advice proposing an age cut-off of 65 years, but stressing the importance of also including patients ≥75 years,Citation6,Citation40,Citation41 especially given the importance of biological age compared to numerical age.Citation5

In addition to procedural difficulties like potential age limits or obtaining legitimate informed consent, other aspects might complicate research in the elderly. These often are inherent with the target population: the possible influence of comorbidities or concomitant medication, malcompliance or unintentional nonadherence to protocols, high dropout rates, functional and cognitive decline, and mortality. In view of the demographic changes, specific age-adapted treatment approaches will have a significant social and health-economic impact that has to be evaluated by means of research in geriatric patients.

Here, we present the results of an empirical study that analyzes the current practice of conducting studies in geriatric trauma patients with respect to handling of IC, choice of inclusion criteria, and assessment of basic patient characteristics in geriatric populations. Finally, we discuss potential improvements and present, in particular, a proposal for the handling of IC in geriatric populations.

Materials and methods

In order to evaluate the current situation, a literature search of the PubMed database, comprising a 10-year period from 2005 to 2015, was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines in 07/2016. The aim of the search was to identify studies in the field of orthopedic and trauma surgery that explicitly focus on a geriatric population (paraphrased with the search terms “geriatric”, “elderly”, and “octogenarians”). The complete search string is shown in the Supplementary material. The resulting articles were screened based on title and abstracts with respect to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Inclusion criteria:

Clinical trials including elderly patient populations in orthopedic and trauma surgery

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), pro- and retrospective studies, and case series.

Exclusion criteria:

Language other than English, German, or French

Unavailability of full text even after contact with the corresponding author

Surgical subspecialty other than orthopedic and trauma surgery (exclusion of spinal surgical trials)

Biomechanical studies, basic science, study protocols, and cost analyses.

The screening was performed by JSJ under the supervision of FJS. For articles meeting the inclusion criteria, full texts were assessed for the prespecified aspects listed in . The items were selected in order to obtain information on the handling of IC, the reported assessment of certain aspects relevant in geriatric populations, and their use as inclusion/exclusion criteria. This assessment was also performed by JSJ under supervision by FJS. Some items were further processed prior to the statistical analysis: countries were grouped by continents, the impact factor was categorized, and the mean age was set to the average of minimal and maximal age in studies not specifically reporting this value. All data were analyzed using SPSS and STATA (Table S1).

Table 1 Screening variables

Results

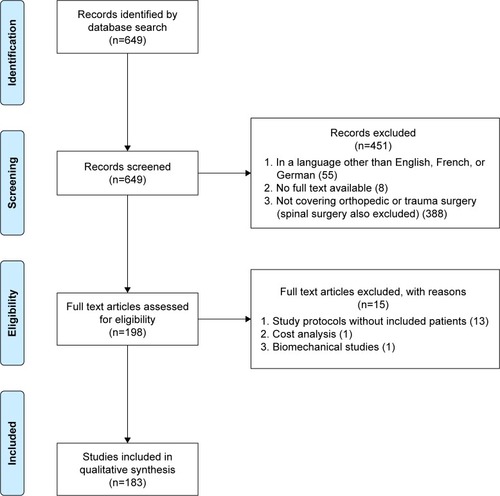

By means of the search strategy reported in the Supplementary material, our search identified 649 articles. After screening based on title and abstract, 183 articles were included in the analysis (see for the PRISMA flowchart).Citation42

depicts the assessment of certain relevant patient characteristics in geriatric populations as well as their use as inclusion/exclusion criteria. The majority of studies did not report on age-related pathologies or the weight/nutrition status, whereas 51% reported on a frailty assessment. The use of walking aids as an indirect aspect of a limitation in independence and the living status upon recruitment were reported in about 10% of all studies. If assessed, frailty, age-related pathologies, incapability of IC, and diagnoses related to cognitive impairment were each used as the exclusion criterion in over one-third of studies.

Table 2 Assessment for aspects of frailty and its impact on inclusion practice

Half of the studies did not include patients above 90 years and half of the studies had a mean age of <80 years, as depicted in . Similarly, in more than half of the studies, the patients’ predominant ASA scores were ASA 1 or 2, while ASA 3 and 4 patients were not present in >10% of all studies.

Table 3 Distribution of patient characteristics across studies

reports the described IC procedures. Only few studies accepted third-party consent, and a minority of articles described a formal assessment of capacity. Of the few articles that document the option of third-party consent, only one acknowledges patients’ assent or dissent, which though is a relevant aspect of patient autonomy in the context of decisional incapacity.

Table 4 Handling of IC

Additionally, more formal study characteristics were evaluated as shown in . Most of the included studies were performed in European countries. Over the years, an increase in the number of studies can be observed. The majority of studies were RCTs; however, only a small proportion was designed as multicenter studies.

Table 5 Study characteristics

In-depth evaluation of these trials revealed a comparison of established techniques or implants in the vast majority of publications. The non-RCT type trials were dominated by case series on similarly established treatment options (). One RCT and two non-RCTs evaluated experimental interventions.

Table 6 Subtypes of trials

The principles of GCP were only rarely mentioned in these studies; similarly, the DoH was mentioned in <20% and ethical approval in about 80% of the studies.

Assessing the possible relation between the methodologic complexities of specific trial subtypes and the documented adherence to ethical guidelines or rigorousness of inclusion and exclusion criteria, we indeed found a respective tendency with more frequent mentioning of ethical guidelines and more rigorous patient selection in RCTs, especially when comparing the RCTs to retrospective case series ().

Table 7 Mention of ethical guidelines and potential restriction of inclusion per trial type

The reporting of ethical standards did not change over time, as shown in . The same holds true for the reporting of recruitment rates as an aspect of external validity, with 73 of the 183 studies specifying inclusion and screening rates. The population size of the included studies ranged from 10 to 1,500 participants. While 111 articles did not report an inclusion rate, 49 RCTs and 24 non-randomized trials reported average recruitment rates of 49% (4%–100%, median 50%) and 66% (16%–100%, median 69.5%), respectively.

Table 8 Distribution of inclusion rate and ethics

Discussion

The analysis of the previously described literature in view of the current regulatory conditions points to a certain potential for improvement at least in the exemplarily chosen area of gerontotraumatology.

The failure of most trials to mention adherence to central ethical guidelines such as the DoH or GCP is astonishing. The implied negligence of central research-ethical principles is hardly acceptable for clinical research in potentially vulnerable patient populations, such as the geriatric.

In addition, there seems to be a tendency toward the exclusion of patients based on old age, comorbidities, frailty, or cognitive impairment (ie, “difficult” patients), but without scientific reasoning. This practice of narrow exclusion criteria puts vulnerable populations at risk, while trying to protect them from exploitation. Ultimately, “evidence” on geriatric patients is generated based on patients lacking the typical characteristics of old age, such as frailty, comorbidities, and cognitive impairment. Therefore, the external validity of such “evidence” is highly questionable. The external validity is further jeopardized by low recruitment rates.

Old, ill, frail, and cognitively impaired patients are not only highly vulnerable to exploitation by doctors, researchers, or other perceived authorities,Citation43 but also suffer from a lack of evidence-based therapeutic approaches and benefits from medical progress. Therefore, exclusion criteria without scientific or legal necessity should be virtually minimized, thus avoiding potentially hazardous consequences such as increasing the barriers for the inclusion of individual patients or necessitating larger patient samples, given the mean recruitment rate of 50% and high dropout rates.

It has to be acknowledged though that, especially considering the aspect of legitimate IC, current ethical guidelines for clinical research fail to support the inclusion of mentally impaired patients/subjects through specific and appropriate advice – an effect that is itself ethically problematic. In consequence, the current practice of obtaining IC is heterogeneous, IC is omitted as in 20% of analyzed trials, or patients are primarily excluded if a straightforward IC seems unrealistic. Clinical research and IC have to be based on the respectful and trustworthy partnership between patient and researcher – not unlike that between patient and physician. Therefore, one option for improvement would be the adjustment of the level of required information to the patient’s respective cognitive capacity resulting from a general neuropsychological assessment. Flooding patients with 20 aspects (as in ICH-GCP E6 paragraph 4.8.10)Citation44 of study conduct renders IC an empty shell. Instead, we propose a stepwise approach in cognitively impaired patients, adapting the extent of imperative information to both the 1) trial-related risks and 2) the difference between the proposed treatments (eg, conservative vs surgical compared to two surgical approaches or different types of splints) to the (assessed) abilities of the patient. This approach is similar to the concept of “low-intervention clinical trials” elaborated in Regulation (EU) No 536/2014,Citation45 which suggests “less stringent rules” for the execution of these trials that are immensely important for the assessment of standards of care. This rule would apply for the vast majority of the above-evaluated trials. Its application could increase overall recruitment rates and, therefore, enhance the external validity of the results.

The propositions below though outreach the concept of “low-intervention clinical trials” as well as the relatively vague guidelines issued by, for example, the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, for example, on “care and treatment of people with dementia (2017)” or “medical treatment and care of people with disabilities (2008, updated 2013)”.Citation46 These guidelines stress the importance of research in geriatric patient populations and give advice on reaching treatment decisions, but fail to give practical guidance for IC to research.

As described previously, there are four dimensions of competence:

Information considering the necessary decision can be understood (dimension of understanding).

The effect and consequences deriving from the choice of one possible alternative can be weighed against those deriving from the choice of another (dimension of appreciation).

Information can be rationally interpreted in the context of a coherent system of norms and values (dimension of reasoning).

A choice can be communicated (dimension of choice).

The measurement of these abilities poses a certain challenge in daily practice, since repeat-back interviews or the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool is time intensive and requires specific experience and training of the assessor. The MMSE, in contrast, is already widely used, available, and validated in many languages with high inter-rater reliability.Citation47,Citation48 The correlation between MMSE or cognitive function and competence is admittedly only loose, though several studies describe thresholds that are clearly associated with clear deficits in competence (≤23), limited competence (23–26), and high probability of preserved competence (>26).Citation28,Citation34–Citation36

Patients with a legal representative can be considered for inclusion in a trial if all of the following statements apply:

The patients show no signs of refusal (ie, give their assent).

The legal representative consents.

Patients with an MMSE score of 23, but without an appointed legal representative can be considered for inclusion in a trial, if all of the following statements apply:

The patients show no signs of refusal (ie, give their assent).

The risk of the trial (ie, both treatments) is negligible.

The patient’s relatives or close relations consent (according to the hierarchy on potential substitute-decision makers imposed by the Swiss Civil Code).Citation49

Patients with an MMSE score between 23 and 26 can be considered for inclusion in clinical trials if all of the following statements apply:

The patient consents.

The patient understands that he/she can refuse to take part without consequences.

The patient understands that other treatment methods are available and that those can be chosen independently of the proposed trial.

The patient understands the principles of the proposed procedures, their risks, and benefits.

The patient understands that neither he/she nor the treating physician can choose the treatment method (in case of randomization).

The patient’s relatives or close relations agree (this oral agreement has the aim of supporting the patient, rather than a legal function).

Patients with an MMSE score over 26 are considered for inclusion independently of the above-mentioned measures.

In order to protect our patients, we propose to include additional third-party consent if competence can be assumed, but MMSE is conspicuous, or if there are indeed signs of incompetence.

In addition, we propose addressing the following further aspects:

First, the perception of the environment might differ in frail elderly patients from the perception in younger patients, given a potential impairment of vision, hearing, adaptation to a new environment, and so on.Citation50–Citation52 Indeed, Inouye and CharpentierCitation53 have described precipitating factors for delirium: the use of physical restraints, malnutrition, more than three medications added, use of bladder catheter, and any iatrogenic event. These could be interpreted as modifiable external risk factors that should be optimized along with factors such as nutrition, electrolyte disturbances, inter-current infection, and so on, which have been identified as predisposing factors.Citation54–Citation56 As part of a respectful partnership, patients should be made as comfortable as possible before being asked to give consent. Overstimulation should be avoided by reducing the surrounding noise, adapting the light, avoiding disturbance, inclusion of close relations, and sufficient analgesia (measured via visual analog scale).Citation57 First, as part of a specific gerontotraumatologic approach, we try to reduce the time in the emergency ward, minimize tubes and lines and, if possible, operate on all patients within a maximum of 24 hours. Furthermore, for clinical research, pictures and big font size for written information should be used to ensure legibility. Second, we suggest a re-evaluation that should take place at least 6 hours after the initial inclusion. To ascertain the understanding of the above-mentioned points, the evaluation with standardized repeat-backCitation58 or a brief assessment of capacityCitation59 should be considered intermittently to ensure proper conduct, especially in an initial phase and for complex interventional trials. This approach might be hampered by the development of preoperative delirium that has been reported to range from 4.4% to 33%,Citation54 depending on the presence of predisposing and precipitating risk factors. We, therefore, consider a close collaboration with family, friends, and close relations essential in order to capture patients’ wishes and life concepts and respect them in clinical research. In case of inter-current cognitive deterioration, the willingness to continue participation in the trial is ascertained at every follow-up visit.

Third, on a more general basis, we also suggest including healthy representatives of the respective target population or patient organizations as reviewers for the protocol, the IC material, and the process of the trial.

These measures ultimately lead to the introduction of the concept of “shared decision making” between patient and researcher. In the realm of treatment decisions, this principle has been welcomed even on the most prestigious forums of medicine,Citation60 and it allows a more individualized process of obtaining the patients’ understanding and response to a recommendation. If we honestly aim at specifically and legitimately including geriatric patients in research and keeping research in these patients attractive, we have to propose, possibly in analogy to the concept of shared decision making, guidelines that are practicable and meet the spirit of the doctrine of IC rather than the letters of bureaucratic forms.

Conclusion

Scientific and medical progress for geriatric patients is currently stagnating, with only little research conducted in this specific population. Literal adherence to guidelines and regulations leads to cumbersome inclusion procedures that discourage researchers and do not protect, but rather disrespect, the right of cognitively impaired and, therefore, vulnerable elderly or geriatric patients to access relevant research. The situation could be improved by adjusting the level of required information to the patients’ cognitive capacity after a simple neuropsychological assessment with certain additional safety measures before final inclusion. The introduction of the concept of shared decision making could additionally help to rectify the currently somewhat precarious research practice. Common sense and explicit respect for the needs of the individual seem to more accurately meet the spirit of the doctrine of IC than following bureaucratic procedures to the letter.

Supplementary material

Search term

(((((surgery[MeSH Major Topic]) OR traumatology[MeSH Major Topic]) OR sur-gery[Title/Abstract]) OR traumatology[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((((geriatric[MeSH Major Topic]) OR elderly[MeSH Major Topic]) OR octogenarian[MeSH Major Topic]) OR geri-atric[Title/Abstract]) OR elderly[Title/Abstract]) OR octogenarian[Title/Abstract]).

Table S1 Items extracted from each article and analyzed variables

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interests in this work.

References

- CherubiniADel SignoreSOuslanderJSemlaTMichelJPFighting against age discrimination in clinical trialsJ Am Geriatr Soc20105891791179620863340

- BroekhuizenKPothofAde CraenAJMooijaartSPCharacteristics of randomized controlled trials designed for elderly: a systematic reviewPLoS One2015105e012670925978312

- Le QuintrecJLBussyCGolmardJLHervéCBaulonAPietteFRandomized controlled drug trials on very elderly subjects: descriptive and methodological analysis of trials published between 1990 and 2002 and comparison with trials on adultsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200560334034415860471

- van DeudekomFJPostmusIvan der HamDJExternal validity of randomized controlled trials in older adults, a systematic reviewPLoS One2017123e0174053e017405828346503

- WrobelPDehlinger-KremerMKlingmannIEthical challenges in clinical research at both ends of lifeDrug Inf J201145189105

- DienerLHugonot-DienerLAlvinoSGuidance synthesis. Medical research for and with older people in Europe: proposed ethical guidance for good clinical practice: ethical considerationsJ Nutr Health Aging201317762562723933874

- WithamMDMcMurdoMEHow to get older people included in clinical studiesDrugs Aging200724318719617362048

- ToerienMBrookesSTMetcalfeCA review of reporting of participant recruitment and retention in RCTs in six major journalsTrials200910111219128475

- DaviesLCookJPriceABeardDWhat are the methodological challenges in the design and conduct of orthopaedic randomised controlled trials comparing surgery and non-operative interventions? A systematic reviewTrials201718Suppl 1O65

- PercivalTMedical Ethics or A Code of Institutes and Precepts, Adapted to the Professional Conduct of Physicians and SurgeonsManchesterS. Russell1803

- American Medical AssociationCode of Medical Ethics of the American Medical Association Originally Adopted at the Adjourned Meeting of the National Medical Convention in PhiladelphiaChicagoAmerican Medical Association Press1897 Available from: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=ien.35558005316472;view=1up;seq=3Accessed January 22, 2019

- BeauchampTLInformed consent: its history, meaning, and present challengesCamb Q Healthc Ethics201120451552321843382

- WillJFA brief historical and theoretical perspective on patient autonomy and medical decision making: part II: the autonomy modelChest201113961491149721652559

- LombardoPAPhantom tumors and hysterical women: revising our view of the Schloendorff caseJ Law Med Ethics200533479180116686248

- Anweisung an die Vorsteher Der Kliniken, Polikliniken und sonstigen Krankenanstalten über medizinische Eingriffe zu anderen ALS zu diagnostischen, Heilund Immunisierungszwecken vom 29 Dezember 1900Zentralblatt für die gesamte Unterrichtsverwaltung Preußen 1901 Available from: http://goobiweb.bbf.dipf.de/Accessed December 18, 2018

- MitscherlichAMielkeFMedizin Ohne Menschlichkeit Dokumente Des Nürnberger ÄrzteprozessesFrankfurt aMFischer Taschenb1989

- TröhlerU R-TSThe Nuremberg Code: The Proceedings in the Medical Case, the Ten Principles of Nuremberg, and the Lasting Effect of the Nuremberg CodeAldershot, UKAshgate Publishing Ltd1998

- World Medical AssociationDeclaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Adopted by the 18th WMA General Assembly, Helsinki, Finland61964 Available from: http//www.cirp.org/library/ethics/helsinki/Accessed January 22, 2019

- BeecherHKEthics and clinical researchN Engl J Med196627424135413605327352

- PappworthMHHuman Guinea Pigs: Experimentation on ManHarmondsworthPenguin Books1969

- CDC [homepage on the Internet] U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htmAccessed July 8, 2018

- Public law 93-348-Juli 12, 1974 88-Stat. National Research Act Available from: http://history.nih.gov/research/downloads/PL93-348.pdfAccessed July 8, 2018

- HHS.gov [homepage on the Internet]The Belmont Report, Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjectAccessed April 18, 1979

- ICH Harmonised Tripartite GuidelineGuideline for good clinical prac-tice E6(R1). ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline199619964i53 Available from https://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6/E6_R1_Guideline.pdfAccessed January 22, 2019

- WomenPFe-HInvolved N Code of federal regulations title 45 department of health and Human services part 46 Protection of human subjects2009 Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/ohrp/policy/ohrpregulations.pdfAccessed January 22, 2019

- Commission Directive 91/507/EEC of 19 July 1991 modifying the Annex to Council Directive 75/318/EEC on the approximation of the laws of member States relating to analytical, pharmacotoxicological and clinical standards and protocols in respect of the test. Available from: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/98ea0b12-c69c-4608-a406-001e48ed29a5/language-enAccessed January 22, 2019

- KochHGReiter-TheilSHHInformed Consent in Psychiatry European Perspectives of Ethics, Law and Clinical PracticeBaden-BadenNomos Verlagagesellschaft1997

- KimSYHAppelbaumPSJesteDVOlinJTProxy and surrogate consent in geriatric neuropsychiatric research: update and recommendationsAm J Psychiatry2004161579780615121642

- DuguetAMBoyer-BeviereBConsent to medical research of vulnerable subjects from the French point of view: the example of consent in research in the case of Alzheimer diseaseMed Law201130461362722397184

- GainottiSFusari ImperatoriSSpila-AlegianiSHow are the interests of incapacitated research participants protected through legislation? An Italian study on legal agency for dementia patientsPLoS One201056e1115020585400

- GaleottiFVanacoreNGainottiSHow legislation on decisional capacity can negatively affect the feasibility of clinical trials in patients with dementiaDrugs Aging201229860761422574633

- United Nations educational, scientific and cultural organization, report of the International bioethics Committee of UNESCO (IBC) on consent, social and human sciences sector, division of ethics of science and technology, bioethics section, SHS/EST/CIB08 Available from: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf000178124Accessed January 22, 2019

- WalaszekAClinical ethics issues in geriatric psychiatryPsychiatr Clin North Am200932234335919486818

- KimSYHCaineEDUtility and limits of the Mini Mental State Examination in evaluating consent capacity in Alzheimer’s diseasePsychiatr Serv200253101322132412364686

- KarlawishJMeasuring decision-making capacity in cognitively impaired individualsNeurosignals2008161919818097164

- MarsonDCIngramKKCodyHAHarrellLEAssessing the competency of patients with Alzheimer’s disease under different legal standards. A prototype instrumentArch Neurol199552109499547575221

- SchaeferLAMacArthur Competence Assessment ToolsKreutzerJSDeLucaJCaplanBEncyclopedia of Clinical NeuropsychologySpringerNew York, NY2011

- World Health OrganizationMen, Ageing and HealthGenevaWorld Health Organization2001163

- RiemSHartwigEHartwigJAlterstraumatologieOrthopädie und Unfallchirurgie up2date2012703187205

- (GMWP) EGMWPMedical Research For and With Older People in Europe2013127 Available from: http://efgcp.organica.eu.com/EFGCP/documents/EFGCPGMWPResearchGuidelinesFinaledited2013052770.pdfAccessed January 21, 2019

- International Council for HarmonizationE7 Studies in Support of Special Populations: Geriatrics Questions & Answers Current Version E7 Q & As Document History. ICH2010 Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm189544.pdfAccessed January 22, 2019

- PRISMA transparent reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses [homepage on the Internet] Available from: http://www.prisma-statement.org/Accessed December 20, 2018

- IvashkovYvan NormanGAInformed consent and the ethical management of the older patientAnesthesiol Clin200927356958019825493

- European Medicines Agency [homepage on the Internet]CPMP/ICH/135/95, ICH topic e 6 (R1) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice2002 Available from: www.ema.europa.eu/pdfs/human/ich/013595en.pdfAccessed July 8, 2018

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European UnionRegulation (EU) 536/2014 of the European Parliament and of The Council of 16 April 2014on Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use, and Repealing Directive 2001/20/EC2014 Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-1/reg_2014_536/reg_2014_536_en.pdfAccessed January 22, 2019

- SAMW/ASSM medical-ethical guidelinesMedical treatment and care of people with disabilities2008 (updated 2013). Available from: https://www.samw.ch/en/Publications/Medical-ethical-Guidelines.htmlAccessed July 8, 2018

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res19751231891981202204

- CullenBO’NeillBEvansJJCoenRFLawlorBAA review of screening tests for cognitive impairmentJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200778879079917178826

- BundesversammlungDEidgenossenschaftDSSchweizerisches Zivilgesetzbuch2011 Available from: https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/19070042/201901010000/210.pdfAccessed January 25, 2019

- InouyeSKWestendorpRGJSaczynskiJSDelirium in elderly peopleLancet2014383992091192223992774

- HomeierDAging: physiology, disease, and abuseClin Geriatr Med201430467168625439635

- ConroySElliottAThe frailty syndromeMedicine20174511518

- InouyeSKCharpentierPAPrecipitating factors for delirium in hos-pitalized elderly personsJAMA1996275118528596223

- SchuurmansMJDuursmaSAShortridge-BaggettLMCleversGJPel-LittelRElderly patients with a hip fracture: the risk for deliriumAppl Nurs Res2003162758412764718

- SmithTOCooperAPeryerGGriffithsRFoxCCrossJFactors predicting incidence of post-operative delirium in older people following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysisInt J Geriatr Psychiatry201732438639628093812

- BlondellRDPowellGEDoddsHNLooneySWLukanJKAdmission characteristics of trauma patients in whom delirium developsAm J Surg2004187333233715006560

- HjermstadMJFayersPMHaugenDFStudies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature reviewJ Pain Symptom Manage20114161073109321621130

- FinkASProchazkaAVHendersonWGEnhancement of surgical informed consent by addition of repeat back: a multicenter, randomized controlled clinical trialAnn Surg20102521273620562609

- JesteDVDunnLBPalmerBWA collaborative model for research on decisional capacity and informed consent in older patients with schizophrenia: bioethics unit of a geriatric psychiatry intervention research centerPsychopharmacology20031711687412768273

- BarryMJEdgman-LevitanSShared decision making – the pinnacle of patient-centered careN Engl J Med Overseas Ed20123669780781