Abstract

Purpose

Approximately, 14% of older adults aged 65 years and over experience a fall within 1 month post-hospital discharge. Adequate self-management may minimize the impact of these falls; however, research is lacking on why some older adults engage in self-management to prevent falls while others do not.

Methods

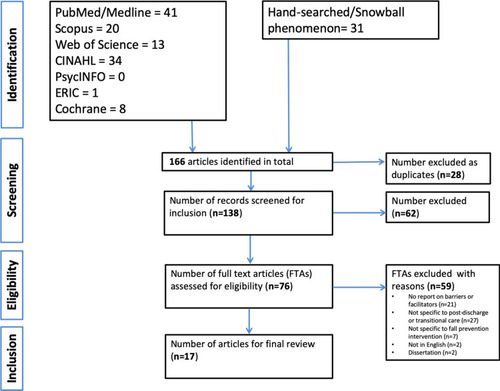

We conducted a scoping review to identify barriers and facilitators to older adults participating in fall-prevention strategies after transitioning home from acute hospitalization. Eligibility criteria were peer-reviewed journal articles published during 2009–2019 which were written in English and contained any of the following keywords or their synonyms: “fall-prevention,” “older adults,” “post-discharge” and “transition care.” We systematically and selectively summarized the findings of these articles using the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines and the PRISMA-ScR reporting guidelines. Seven bibliographic databases were searched: PubMed/MEDLINE, ERIC, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. We used the Capability-Opportunity-Motivation-Behavior (COM-B) model of health behavior change as a framework to guide the content, thematic analysis, and descriptive results.

Results

Seventeen articles were finally selected. The most frequently mentioned barriers and facilitators for each COM-B dimension differed. Motivation factors include such as older adults lacking inner drive and self-denial of being at risk for falls (barriers) and following-up with older adults and correcting inaccurate perceptions of falls and fall-prevention strategies (facilitators).

Conclusion

This scoping review revealed gaps and future research areas in fall prevention relative to behavioral changes. These findings may enable tailoring feasible fall-prevention interventions for older adults after transitioning home from acute hospitalization.

Introduction

In late 2019, the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid ServicesCitation1 announced a rule related to the Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act that post-acute rehabilitation service sectors must empower and engage patients to actively participate in their discharge planning. This rule is intended to reduce patients’ chances of rehospitalization after transitioning home from the hospital or other post-acute rehabilitation services.Citation1 Post-hospital fall-related injuries are a leading diagnosis upon readmission among Medicare patients, particularly for those originally admitted with fall-related injuries or cognitive impairment.Citation2 Approximately 14% of older adults aged 65 and over have experienced a fall within 1 month post-hospital discharge,Citation3 and 40% of older adults have fallen within 6 months after discharge.Citation3–Citation5 Older adults may require additional assistance to remain independent in their homes as they age and remain fall-free within the first month post-hospital discharge.Citation6

Many factors cause falls, including impaired cognition, mobility, gait, and balance; a history of falling; and dependence in daily living activities.Citation7 In 2009, in the US, 31.7% of adults aged ≥65 years, who experienced a fall, had a fall-related injury.Citation8 Of the approximately 52 million older adults in the US (5.7%), over 3 million are treated in emergency departments for fall-related injuries annually, and over 800,000 of them are hospitalized. Over half of all post-hospital fall-related injuries lead to other injuries (eg, a fractured hip), functional decline,Citation4 or rehospitalizationCitation4,Citation5 with substantial health-care costs.Citation3 Recent studies have shown that adequate self-management may minimize the impact of falls in older adults.Citation9–Citation16 However, research is lacking on why some older adults engage in self-management actions and behaviors to prevent falls while others do not.Citation15 Research is needed to explore possible barriers and facilitators to engaging older patients in preventing falls post-hospitalization.Citation17–Citation19

Study Rationale

Hospitals urgently need to assist with post-hospital transitional efforts to prevent falls to address the burden and costs of these falls.Citation2 Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving multifactorial patient-centered fall-prevention interventions in acute care settings have demonstrated reduced fall rates by tailoring patient education and care plans based on patients’ fall risks.Citation20–Citation23 Clinical practice guidelines recommend multifactorial interventions that assess individual risk factors, followed by specific interventions targeting those risk factors to prevent older adults from falling.Citation15,Citation24

Because of the increasing number of older adults at risk, the physical and psychological impact associated with falls, and the high associated health-care costs, additional research is warranted to design and test age-related and culturally sensitive interventions for older adults post-hospitalization.Citation2,Citation25,Citation26

Study Objectives

This scoping review aimed to identify barriers and facilitators to older adults participating in fall-prevention activities after transitioning home from acute hospitalization. The short-term goal of this research was to use the results of the synthesized review to design patient-centered fall-prevention strategies for older adults transitioning home after hospitalization. We intend to use the framework for the study of complex mHealth interventions in diverse cultural settings by Maar et alCitation27 to develop fall-prevention interventions, emphasizing process evaluation to engage potential users (ie, older adults) and other stakeholders (ie, caregivers, health-care providers, and policymakers). The results may ignite future research to codevelop interventions that older adults can easily adopt to prevent falls, for example, by identifying major active components, incorporating technology to facilitate adoption, ensuring cultural congruence, and understanding the unintended consequences.Citation27

Materials and Methods

We conducted a scoping review and systematically and selectively summarized the research findings of the identified articles. We used the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guideline to guide the methodology,Citation28 which was based on an earlier methodological framework by Arksey and O’Malley.Citation29 We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) as our reporting guideline.Citation30 As a scoping review manuscript, the study presented in this paper does not require Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee oversight.

Protocol and Registration

This study had no pre-published or registered protocol before its commencement.

Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria included peer-reviewed journal articles in all designs that were published between 2009 and 2019, were written in English, and assessed a combination of any of the following keywords or their synonyms: “fall-prevention,” “older adults,” “post-discharge” and “transition care.” We formed the idea of this study in mid-2019 and set the review start date as 2009. Since we included articles in all designs, including systematic review articles, we considered the review period from 2009 to 2019 as being current and practical to conduct a thorough scoping review.

Information Sources

We consulted with a librarian to assist in defining the keywords and combinations. We searched seven electronic bibliographic databases (PubMed/MEDLINE, ERIC, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Web of Science) and used a syntax composed of all identified keywords and their synonyms.

Search Strategy

We conducted the initial search between September 2, 2019, and September 15, 2019, and an updated search on February 5, 2020. We also hand-searched the references of the included articles and applied the “snowball phenomenon” to identify relevant peer-reviewed articles in the methodological framework. Gray literature searches were excluded from our search strategy. lists the search syntax used in the library search for relevant journal articles.

Selection of Evidence Sources

We employed two iterative stages to identify articles. In the first stage, we screened the article titles and abstracts after collating the articles and removing duplicates. We then evaluated these articles by carefully reading the full text. In the second stage, two authors (HMT and UO) independently screened and reviewed all full-text articles and assigned a score of either 0 or 1 (0 = not relevant; 1 = relevant) to each article. The overall reviewer reliability score (kappa score) was calculated, and any disagreements were resolved by consensus. The overall kappa score was 0.837 (standard error = 0.062; p<0.0001). All citations were imported or manually entered using the reference manager, Endnote X9.Citation31

Data Charting and Items

We extracted data from the final selected articles based on preidentified data items: author(s), title and date of publication, study type and design, materials and methodology, data collection methods, stage of the care continuum on which the study focused, setting, barriers or facilitators, limitations, and lessons learned. For each selected study, the authors (HMT and UO) extracted and coded the data as barriers and facilitators to fall-prevention compliance in intervention studies where fall-prevention strategies recorded the negative and positive impacts, respectively, in decreasing fall occurrences at home post-hospitalization. For example, we abstracted information regarding barriers when the intervention provided limited success in reducing falls post-discharge. All data were compiled into a spreadsheet using Microsoft Excel 2016.Citation32

Critical Appraisal of Individual Evidence Sources

Given the varying study designs and methodologies used in the included studies, we appraised their characteristics and methodological quality. We assessed the methodological quality of each included article using the JBI critical appraisal toolsCitation33 for qualitative studies, randomized clinical studies, systematic reviews, prospective studies, and cross-sectional studies. We used the methodological quality rating to verify the quality of the studies included in this scoping review. Readers may obtain a copy of the appraisal results from the corresponding author.

Synthesis of Results

We used the Capability-Opportunity-Motivation-Behavior (COM-B) model of health behavior changeCitation34,Citation35 to guide the content, thematic analysis, and descriptive results of the review synthesis. The COM-B model conceptualizes behavioral change strategies into three groups: capability, opportunity, and motivation. The use of this model could support intervention designs and improve the process of intervention evaluation and theory development.Citation34,Citation35 We characterized the behavior change strategies related to preventing falls when older adults transitioned home after hospitalization. Fall-prevention strategies can address a patient’s capability, opportunity, or motivation singly or jointly because these three components interact to generate patients’ behavioral changes.Citation34,Citation35

Two authors (HMT and UO) met ten times via video conference to discuss concerns, resolve conflicts, and review the research protocols to ensure strict adherence. The other author (EL), a behavioral scientist, joined two video conferencing calls and independently reviewed and commented on the results. Several disagreements among the three authors (HMT, UO, EL) were identified (ie, themes, subthemes, and themes being regrouped into either the capability, opportunity, or motivation category). Conflicting themes were resolved by consensus during the conference calls or e-mail communication.

Results

Selection of Evidence Sources

We identified 166 articles by searching the library databases (n=135) and by hand-searching/snowballing (n=31). Of these 166 articles, 28 were excluded as duplicates, resulting in 138 articles for screening. One author (UO) independently screened the article abstracts and titles, after which, 62 articles were excluded. Subsequently, the full text of the remaining 76 articles was screened for selection and inclusion based on relevance to the research question. Finally, 17 articles were included in this study. Studies were excluded during the final screening if they were not written in English, did not report barriers or facilitators to fall-prevention intervention, did not specify falls or fall-prevention interventions, did not specify post-discharge or transitional care, or were not journal articles ().

All included articles were original studies or systematic reviews related to post-discharge or transitional care and fall prevention among older adults. The authors (HMT and UO) agreed to add two systematic reviews.Citation36,Citation37 Although these two systematic review articlesCitation36,Citation37 did not fully meet the eligibility criteria for studies on post-hospitalization care, the authors (HMT and UO) concluded that both articlesCitation36,Citation37 provided in-depth information that elucidated fall-prevention strategies and characteristics spanning the care continuum (including post-discharge).

Characteristics of Evidence Sources

summarizes the general and methodological characteristics of the 17 reviewed studies. Ten of the reviewed articles (58.8%) were published in 2009–2014,Citation5,Citation38-46 and seven (41.2%) were published in 2015–2019.Citation19,Citation36,Citation37,Citation47-50 Six were conducted in Australia,Citation5,Citation19,Citation41-43,Citation45 five in the United States,Citation38,Citation39,Citation48-50 and three in the United Kingdom.Citation36,Citation40,Citation44 Six (35.3%) used qualitative methods,Citation36,Citation38,Citation40,Citation44,Citation49,Citation50 six (35.3%) used mixed methods,Citation19,Citation37,Citation41-43,Citation46 and five (29.4%) used quantitative methods.Citation5,Citation39,Citation45,Citation47,Citation48 Five (29.4%) targeted post-hospital discharge for up to 1 month,Citation5,Citation39,Citation43,Citation47,Citation50 and three (17.6%) targeted post-hospital discharge for up to 6 months.Citation19,Citation41,Citation42

Ten studies (58.8%) recruited patients during hospital stays;Citation5,Citation19,Citation39,Citation41-44,Citation47,Citation49,Citation50 four (23.5%) recruited patients from the community.Citation38,Citation40,Citation46,Citation48 In ten studies (58.8%), an interdisciplinary team delivered the fall-prevention intervention.Citation39–Citation42,Citation44–Citation47,Citation49,Citation50 Thirteen studies (76.5%) included only patients as the fall-prevention intervention recipients.Citation5,Citation38-42,Citation44–Citation50 Four studies were review studies.Citation19,Citation36,Citation37,Citation43 For the intervention, nine studies (52.9%) included follow-up events by phone, mail or e-mail.Citation5,Citation38,Citation39,Citation41,Citation42,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49,Citation50 Seven studies (41.2%) used individual-based interventions,Citation38–Citation40,Citation44,Citation48-50 and five (29.4%) used group-based interventions.Citation5,Citation41,Citation42,Citation45,Citation47

Individual Evidence Sources

summarizes the characteristics of the included studies.

Synthesis of the Results

presents the barriers to older adults participating in fall-prevention strategies post-hospital discharge, and presents the facilitators. Barriers and facilitators were categorized by frequency of occurrence. Results (themes) in and were coded with identifiers corresponding to the COM-B framework,Citation34,Citation35 where “C” refers to capability, “O”, opportunity and “M”, motivation for the respective barriers and facilitators. Subthemes were similarly categorized under major themes using the same coding strategy.

Barriers

Four themes were identified as capability-related barriers: frailty due to advancing age,Citation36,Citation39,Citation43,Citation46,Citation51 language and communication,Citation40,Citation41,Citation43,Citation46 education/literacy levels,Citation43,Citation46 and health-related problems ().Citation36,Citation37,Citation40,Citation42,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49 Physical healthCitation37,Citation42,Citation46 and general health issuesCitation36,Citation40,Citation47,Citation49 were the most frequently mentioned capability-related barriers limiting participation in fall-prevention interventions (7 studies, 41.2%).Citation36,Citation37,Citation40,Citation42,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49

Four themes were identified as opportunity-related barriers: lack of institutional support,Citation37,Citation38,Citation40-43,Citation46,Citation49 lack of social and community support,Citation37 fall-prevention strategies requiring additional designs,Citation19,Citation41,Citation42,Citation49 and lack of access to intervention.Citation36,Citation40,Citation48,Citation49 Eight studiesCitation37,Citation38,Citation40-43,Citation46,Citation49 (47.1%) implied lack of institutional support for fall-prevention programs as the most common opportunity-related barrier; five of these studiesCitation37,Citation38,Citation40,Citation42,Citation49 mentioned that health staff were disinterested in promoting fall-prevention interventions due to heavy clinical workloadCitation37,Citation38,Citation52 and lack of understanding the program.Citation37,Citation40,Citation42

Four themes were identified as motivation-related barriers: lack of motivation to carry out or sustain involvement in the fall-prevention intervention post-hospital discharge or during hospitalization,Citation36,Citation37,Citation41-44,Citation48,Citation49 self-denial of risk for falls,Citation36,Citation50 difficulty transitioning between daily living activities and fall-prevention strategies,Citation36 and enthusiasm fatigue.Citation37 The most frequently mentioned motivation-related barrier was lack of motivationCitation36,Citation37,Citation41-44,Citation48,Citation49 (8 articles, 47.1%), which included lack of motivation to participate because of emotional/mental-related issues,Citation43,Citation49 lacking the will to join because of spiritual beliefs conflicting with fall-prevention practice (eg, practicing Tai-Chi may interfere with spiritual beliefs),Citation37 behavior and attitudes towards fall-prevention hindering participation (eg, overconfident in their ability to prevent falls)Citation36,Citation37,Citation41,Citation42,Citation44,Citation48 and older adults lacking confidence to prevent falls.Citation48,Citation49

Facilitators

Four themes were identified and categorized as capability-related facilitators: being younger older adults (because they considered themselves fit and more inclined to participate),Citation46 use of language and communication aids (eg, interpreters and audiovisual tools),Citation36,Citation41,Citation43,Citation46,Citation49 nature of the fall-prevention strategy and personal preference,Citation5,Citation48 and adaptation and resiliency to new strategies aiding mobility ().Citation41,Citation46,Citation50 Use of language and communication aides was the most mentioned theme (5 articles, 29.5%).Citation36,Citation41,Citation43,Citation46,Citation49

We identified 12 themes for opportunity-related facilitators (). The first most mentioned theme was institutional and organizational support in assisting in fall-prevention programs (8 articles, 47.1%)Citation36,Citation37,Citation40-43,Citation49,Citation50 such as providing funding and facility for the programs,Citation37,Citation42 providing financial incentives for health staff who educate older adults on participating in these programs,Citation40 making available mobility support for older adults to move freely without difficulty (eg, wheelchair ramps, visual aids for slippery surfaces),Citation42,Citation46 and providing communication aids to facilitate comprehension.Citation36,Citation43,Citation49,Citation50 The second most mentioned theme was encouragement and social support for older adults (8 articles, 47%),Citation5,Citation36,Citation37,Citation41,Citation44,Citation46,Citation48,Citation49 such as support and empathy from family members,Citation5,Citation36,Citation37,Citation46,Citation49 fall-prevention program facilitators,Citation36,Citation37,Citation48 healthcare providers,Citation37,Citation41,Citation48 community,Citation36,Citation37 and peer-to-peer support.Citation37,Citation44 The third most mentioned theme was prolonged community engagement and relationship building with older adults to learn how to mitigate barriers to participation (4 articles, 23.5%).Citation5,Citation36,Citation41,Citation48 This theme included two subthemes: (1) engaging older adults in designing fall-prevention programs collaboratively and inclusively (ie, listening to them to know what they want and learning how to meet their needs regarding preventing falls),Citation5,Citation41 and (2) engaging older adults respectfully and with sensitivity (eg, in considering their time/schedules, physical limitations).Citation36,Citation48

Three themes were identified for motivation-related facilitators: (1) following up with older adults to clarify their understanding of the fall-prevention program (2 articles, 11.8%),Citation49,Citation50 (2) changing inaccurate perceptions of falls and fall-prevention strategies (5 articles, 29.4%)Citation36–Citation38,Citation46,Citation50 such as the perception of the need for fall-prevention programs (1 article, 5.9%),Citation38 and perception of the benefits of fall-prevention programs (4 articles, 23.5%),Citation36,Citation37,Citation46,Citation50 and (3) seeing personal gain, benefits and improvements in gait and balance (1 article, 5.9%).Citation36

Discussion

This scoping review synthesized evidence regarding barriers and facilitators to older adults participating in fall-prevention strategies after transitioning home from acute hospitalization. We used the COM-B framework to categorize the barriers and facilitators in the context of behavior modifications. The success of a behavior modification involved elements of an individual’s capability (physical or psychological factors), opportunities (physical, social, or institutional factors), and/or motivation (impulsive or reflective factors),Citation35 and the findings were summarized under these three factors.

Capability factors in the COM-B framework included personal characteristics (eg, age) or intrinsic factors among older adults.Citation34 Regarding capability factors, physical healthCitation37,Citation42,Citation46 and general health issuesCitation36,Citation40,Citation47,Citation49 were the major capability-related barriers limiting participation in fall-prevention interventions. Use of language and communication aides was found to be the most helpful.Citation36,Citation41,Citation43,Citation46,Citation49

Opportunity factors in the COM-B framework included extrinsic or environmental factors among older adults that enabled or prompted their participation.Citation34 Lack of institutional support for fall-prevention programs was the key opportunity-related barrier.Citation37,Citation38,Citation40-43,Citation46,Citation49 Several studiesCitation37,Citation38,Citation40,Citation42,Citation49 found that health staff often lacked a good understanding of fall-prevention programsCitation37,Citation40,Citation42 or were disinterested in promoting fall-prevention interventions due to heavy clinical workloads.Citation37,Citation38,Citation52 In contrast, the top three opportunity-related facilitators were institutional and organizational support in assisting fall-prevention programs,Citation36,Citation37,Citation40-43,Citation49,Citation50 encouragement and social support for older adults,Citation5,Citation36,Citation37,Citation41,Citation44,Citation46,Citation48,Citation49 and engaging older adults to mitigate barriers to participating in fall-prevention solutions.Citation5,Citation36,Citation41,Citation48

Motivational factors in the COM-B framework involved the reflexive and impulsive processes that guide conscious decision-making.Citation34 These included a lack of inner drive to carry out or continue involvement in fall-prevention interventions after hospital discharge or during hospitalization,Citation36,Citation37,Citation41-44,Citation48,Citation49 self-denial of being at risk for falls,Citation36,Citation50 having difficulty transitioning between daily living activities and fall-prevention strategies,Citation36 and enthusiasm fatigue.Citation37

The three main motivation-related facilitators were following up with older adults,Citation49,Citation50 identifying and correcting inaccurate perceptions of falls and fall-prevention strategies,Citation36–Citation38,Citation46,Citation50 such as the need forCitation38 and benefits of these programs,Citation36,Citation37,Citation46,Citation50 and ensuring that older adults realize the personal gain, benefits, and improvements in gait and balance.Citation36

In summary, we examined barriers and facilitators to fall-prevention compliance among older adults and how these barriers and facilitator guide behavioral changes following discharge from acute care. Using the innovative approach of the COM-B model of health behavior changeCitation34,Citation35 to guide this thematic analysis elicited essential insights. The most frequently mentioned barriers and facilitators in each COM-B dimension differed greatly ( and ). The identified gaps could shed light on future fall-prevention intervention designs focusing on behavioral changes in older adults.

Practical Implications

This scoping review provided a practical understanding of fall prevention relative to behavioral changes and revealed gaps and future research areas in fall prevention. The findings may help guide researchers when co-developing and co-evaluating fall-prevention interventions “with” older adults “for” older adults to avoid preventable falls and fall-related injuries after transitioning home from acute hospitalization. Two studiesCitation5,Citation41 suggested engaging older adults in co-designing fall-prevention interventions as a strategy to develop sustainable programs that older adults can easily adopt.

Study Limitations

We identified two study limitations. First, the varied periods of care transition in each study (eg, from post-hospital discharge up to 8 days to up to 12 months) and the diverse locations for patient recruitment (eg, during hospitalization or from the community) may have contributed to selection bias of the reviewed articles. For example, two reviewed studiesCitation36,Citation37 addressed fall prevention across the care continuum. Second, appraisal of the risk of bias indicated potential bias in the measurement approaches. Methodological limitations of some included studies could have affected the evidence.

Additionally, this study took an innovative approach to follow the COM-B model of health behavior change as a framework to identify the barrier and facilitator themes; by using this framework, we hope to facilitate future systematic development of falls prevention interventions. The Behavior Change Wheel program planning model provides guidance for matching intervention components to specific theoretical components of the COM-B model. Future research may build on the findings of this scoping review to rigorously and systematically develop patient-centered fall-prevention strategies for behavioral change and hospitals’ fall-prevention policies. For example, clinicians in the hospital settings and health researchers could use the results of this review to help them refine hospital policies related to fall prevention to facilitate transition home after an acute hospitalization (eg, increasing mobility).

Conclusion

This scoping review used the COM-B model of health behavior changeCitation34,Citation35 as a framework to identify barriers and facilitators to older adults participating in activities to prevent falls after transitioning home from acute hospitalization. The critical barriers and key facilitators in each COM-B dimension differed greatly. The findings of this review may help tailor feasible fall-prevention interventions for older adults after transitioning home from acute hospitalization.

Table 1 General and Methodological Characteristics of All Included Articles (n=17)

Table 2 Characteristics of the Included Studies (n=17)

Table 3 Barriers to Older Adults Participating in Fall-Prevention Strategies After Transitioning Home from Hospitalization (n=17 Articles)

Table 4 Facilitators to Older Adults Participating in Fall-Prevention Strategies After Transitioning Home from Hospitalization (n=17 Articles)

Box 1 Keyword Search Syntax and Search Strategy for the PubMed/MEDLINE, ERIC, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Web of Science Databases

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Centre for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Revisions to Requirements for Discharge Planning for Hospitals, Critical Access Hospitals, and Home Health Agencies, and Hospital and Critical Access Hospital Changes to Promote Innovation, Flexibility, and Improvement in Patient Care. The Daily Journal of the United States Government; 2019 National Archives, a rule by the CMS on published September 30, 2019:51836-51884. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-09-30/pdf/2019-20732.pdf. Accessed 523, 2020.

- Hoffman GJ, Liu H, Alexander NB, Tinetti M, Braun TM, Min LC. Posthospital fall injuries and 30-day readmissions in adults 65 years and older. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194276. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.427631125100

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Fall data: cost of older adult falls; 9 19, 2019 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/Falls/fallcost.html. Accessed 523, 2020.

- Milat AJ, Watson WL, Monger C, Barr M, Giffin M, Reid M. Prevalence, circumstances and consequences of falls among community-dwelling older people: results of the 2009 NSW falls prevention baseline survey. N S W Public Health Bull. 2011;22(3–4):43–48. doi:10.1071/NB1006521631998

- Hill AM, Etherton-Beer C, Haines TP. Tailored education for older patients to facilitate engagement in falls prevention strategies after hospital discharge–a pilot randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63450. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.006345023717424

- Administration for Community Living. 2018 Profile of Older Americans. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Community Living; 2018 Available from: https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2018OlderAmericansProfile.pdf. Accessed 523, 2020.

- Schwendimann R, Buhler H, De Geest S, Milisen K. Falls and consequent injuries in hospitalized patients: effects of an interdisciplinary falls prevention program. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6(1):69. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-6-6916759386

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. The state of aging and health in America 2013; 2013 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/State-Aging-Health-in-America-2013.pdf. Accessed 523, 2020.

- Duckworth M, Adelman J, Belategui K, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of engaging patients and their families in the three-step fall prevention process across modalities of an evidence-based fall prevention toolkit: an implementation science study. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(1):e10008. doi:10.2196/1000830664454

- Dykes PC, Duckworth M, Cunningham S, et al. Pilot testing fall tIPS (Tailoring interventions for patient safety): a patient-centered fall prevention toolkit. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(8):403–413. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.05.00228738986

- McDonald KM, Bryce CL, Graber ML. The patient is in: patient involvement strategies for diagnostic error mitigation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22 Suppl 2:ii33–ii39. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001623

- Morgan L, Flynn L, Robertson E, New S, Forde-Johnston C, McCulloch P. Intentional Rounding: a staff-led quality improvement intervention in the prevention of patient falls. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(1–2):115–124. doi:10.1111/jocn.1340127219073

- Opsahl AG, Ebright P, Cangany M, Lowder M, Scott D, Shaner T. Outcomes of adding patient and family engagement education to fall prevention bundled interventions. J Nurs Care Qual. 2017;32(3):252–258. doi:10.1097/NCQ.000000000000023227662462

- Reuben DB, Gazarian P, Alexander N, et al. The strategies to reduce injuries and develop confidence in elders intervention: falls risk factor assessment and management, patient engagement, and nurse co-management. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(12):2733–2739. doi:10.1111/jgs.1512129044479

- Schnock KO, Howard EP, Dykes PC. Fall prevention self-management among older adults: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(5):747–755. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.00730885516

- Schnock KO, Snyder JE, Fuller TE, et al. Acute care patient portal intervention: portal use and patient activation. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(7):e13336. doi:10.2196/1333631322123

- Hill AM, Etherton-Beer C, McPhail SM, et al. Reducing falls after hospital discharge: a protocol for a randomised controlled trial evaluating an individualised multimodal falls education programme for older adults. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e013931. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013931

- Naseri C, McPhail SM, Haines TP, et al. Evaluation of tailored falls education on older adults’ behavior following hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(11):2274–2281. doi:10.1111/jgs.1605331265139

- Naseri C, Haines TP, Etherton-Beer C, et al. Reducing falls in older adults recently discharged from hospital: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2018;47(4):512–519. doi:10.1093/ageing/afy04329584895

- Ang E, Mordiffi SZ, Wong HB. Evaluating the use of a targeted multiple intervention strategy in reducing patient falls in an acute care hospital: a randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(9):1984–1992. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05646.x21507049

- Avanecean D, Calliste D, Contreras T, Lim Y, Fitzpatrick A. Effectiveness of patient-centered interventions on falls in the acute care setting compared to usual care: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15(12):3006–3048. doi:10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003331

- Dykes PC, Carroll DL, Hurley A, et al. Fall prevention in acute care hospitals: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1912–1918. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.156721045097

- Healey F, Monro A, Cockram A, Adams V, Heseltine D. Using targeted risk factor reduction to prevent falls in older in-patients: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2004;33(4):390–395. doi:10.1093/ageing/afh13015151914

- Yardley L, Donovan-Hall M, Francis K, Todd C. Attitudes and beliefs that predict older people’s intention to undertake strength and balance training. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(2):P119–P125. doi:10.1093/geronb/62.2.p11917379672

- Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al.; US Preventive Services Task Force. Interventions to Prevent Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1696‐1704. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.3097.

- The American Geriatrics Society. AGS comments to senate special committee on aging on falls prevention; 7 2, 2019 Available from: https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/AGS%20Comments%20Senate%20Aging%20Request%20on%20Falls%20Prevention%20%287%202%2019%29%20FINAL_1.pdf. Accessed 523, 2020.

- Maar MA, Yeates K, Perkins N, et al. A framework for the study of complex mhealth interventions in diverse cultural settings. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(4):e47. doi:10.2196/mhealth.704428428165

- Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141‐146. doi:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467‐473. doi:10.7326/M18-0850

- Endnote X9.2 MacOS Commercial Software [Computer Program]. Thomson Reuters Corporation; 2019.

- Microsoft Excel Version 16.32 [Computer Program]. Microsoft Corporation; 2016.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools. Adelaide, SA; 2014 Available from: https://joannabriggs.org/ebp/critical_appraisal_tools. Accessed 523, 2020.

- Michie S, van SMM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-4221513547

- Michie SA, Atkins L, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions: The COM-B Self-Evaluation Questionnaire Can Be Found Pp. 68–69. [Permission granted by Dr. Michie to use this questionnaire] Great Britain: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

- Finnegan S, Bruce J, Seers K. What enables older people to continue with their falls prevention exercises? A qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4):e026074. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026074

- Sandlund M, Skelton DA, Pohl P, Ahlgren C, Melander-Wikman A, Lundin-Olsson L. Gender perspectives on views and preferences of older people on exercise to prevent falls: a systematic mixed studies review. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):58. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0451-228212622

- Calhoun R, Meischke H, Hammerback K, et al. Older adults’ perceptions of clinical fall prevention programs: a qualitative study. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:867341. doi:10.4061/2011/86734121629712

- Davenport RD, Vaidean GD, Jones CB, et al. Falls following discharge after an in-hospital fall. BMC Geriatr. 2009;9:53. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-9-5319951431

- Dickinson A, Horton K, Machen I, et al. The role of health professionals in promoting the uptake of fall prevention interventions: a qualitative study of older people’s views. Age Ageing. 2011;40(6):724‐730. doi:10.1093/ageing/afr111

- Hill AM, Hoffmann T, Beer C, et al. Falls after discharge from hospital: is there a gap between older peoples’ knowledge about falls prevention strategies and the research evidence? Gerontologist. 2011;51(5):653‐662. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr052

- Hill AM, Hoffmann T, McPhail S, et al. Factors associated with older patients’ engagement in exercise after hospital discharge. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(9):1395‐1403. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2011.04.009

- Lee DCA, Pritchard E, McDermott F, Haines TP. Falls prevention education for older adults during and after hospitalization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Educ J. 2013;73(5):530–544. doi:10.1177/0017896913499266

- McMillan L, Booth J, Currie K, Howe T. ‘Balancing risk’ after fall-induced hip fracture: the older person’s need for information. Int J Older People Nurs. 2014;9(4):249‐257. doi:10.1111/opn.12028

- Vogler CM, Sherrington C, Ogle SJ, Lord SR. Reducing risk of falling in older people discharged from hospital: a randomized controlled trial comparing seated exercises, weight-bearing exercises, and social visits. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(8):1317‐1324. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.030

- Wong EL, Woo J, Cheung AW, Yeung PY. Determinants of participation in a fall assessment and prevention programme among elderly fallers in Hong Kong: prospective cohort study. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(4):763‐773. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05535.x

- Agmon M, Zisberg A, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G, Shadmi E. Anxiety symptoms during hospitalization of elderly are associated with increased risk of post-discharge falls. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(6):951‐958. doi:10.1017/S1041610215002306

- Kiami SR, Sky R, Goodgold S. Facilitators and barriers to enrolling in falls prevention programming among community dwelling older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;82:106‐113. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2019.01.006

- Shuman C, Liu J, Montie M, et al. Patient perceptions and experiences with falls during hospitalization and after discharge. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;31:79‐85. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2016.01.009

- Shuman CJ, Montie M, Hoffman GJ, et al. Older adults’ perceptions of their fall risk and prevention strategies after transitioning from hospital to home. J Gerontol Nurs. 2019;45(1):23‐30. doi:10.3928/00989134-20190102-04

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Preventing falls in hospitals: A toolkit for improving quality of care. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ publication No. 13-0015-EF; 1 2013 Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/hospital/fallpxtoolkit/index.html. Accessed 523, 2020.

- Shipman KE, Stammers J, Doyle A, Gittoes N. Delivering a quality-assured fracture liaison service in a UK teaching hospital-is it achievable? Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(10):3049‐3056. doi:10.1007/s00198-016-3639-y