Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to determine whether unintentional weight loss in older women predicts an imminent transition out of low-level care (either to higher-level care or by mortality).

Methods

Fifty-three Australian women, ambulatory while living in low-level care and requiring minimal assistance, were studied. At baseline, when the women were aged (mean ± standard deviation) 86.2 ± 5.3 years, body composition was assessed by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, dietary intake was determined by a three-day weighed food record, a venous blood sample was taken, and both muscle strength and physical functioning were measured. The women were then followed up for 143 weeks to record the composite outcome of transfer to high-level care or mortality.

Results

During follow-up, unintended loss of body weight occurred in 60% of the women, with a mean weight loss of −4.6 ± 3.6 kg. Seven women (13.2%) died, and seven needed transfer to high-level care. At baseline, those who subsequently lost weight had a higher body mass index (P < 0.01) because they were shorter (P < 0.05) but not heavier than the other women. Analysis of their dietary pattern revealed a lower dietary energy (P < 0.05) and protein intake (P < 0.01). The women who lost weight also had lower hip abductor strength (P < 0.01), took longer to stand and walk (P < 0.05), and showed a slower walking speed (P < 0.01). Their plasma C-reactive protein was higher (P < 0.05) and their serum albumin was lower (P < 0.01) than women who did not lose weight. Nonintentional weight loss was a significant predictor of death or transfer to high care (hazards ratio 0.095, P = 0.02).

Conclusion

Weight loss in older women predicts adverse outcomes, so should be closely monitored.

Keywords:

Introduction

Weight loss in the aged is relatively common. Older people are susceptible to weight loss following stress, illness, loss of a spouse, or as a result of the ageing process itself, which can decrease appetite and reduce taste and smell.Citation1–Citation3 Smoking or the presence of disability exacerbates this process,Citation3 as does dementia and the side effects of polypharmacy.Citation2 Previous studies indicate that weight loss is associated with a higher risk of mortality, both in community-dwellingCitation3–Citation6 and institutionalized older people living in high-level care.Citation7 However, in Australia, one quarter of the people (about 39,600) living in care reside in establishments providing low-level rather than high-level care.Citation8 Low-level care provides accommodation and assistance with personal care, but nursing support is limited.Citation8 It is not known whether the occurrence of unintentional weight loss in older people living in these circumstances is an indicator of increased risk of mortality or of the need for higher levels of care. This question has importance because their transfer to more intensive care with 24-hour nursing is associated with a substantially greater health cost (approximately $A604 per week) and a reduced quality of life.Citation9 Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the associations between weight loss and transfer to high-level care or risk of mortality in a cohort of older Australian women residing in low-level care.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

Participants were elderly women from 14 low-level aged care facilities in metropolitan Melbourne. Low-level care provides accommodation, assistance with personal care, and basic nursing care (eg, medication and health monitoring), but does not provide 24-hour nursing care.Citation8

The present study was nested within a larger two-year cluster-design, randomized controlled trial that took place when the women had not been subject to any direct intervention.Citation10 Women were enrolled if they were ambulatory and able to self-feed. All were receiving assistance with activities such as personal care, whether this was required or not. While 78 women were recruited, only the 53 for whom there were data for change in body weight were included. These 53 women did not differ in age, body mass index, or medical conditions from the remaining 25 women for whom weight change data were unavailable. Data were obtained at the initial, mid-term, and final assessment of participants enrolled in the larger randomized controlled trial. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, Austin Health, and by the Standing Committee on Ethics in Research involving Humans, Monash University.

Weight assessment and baseline characteristics

Body weight was taken at baseline and during the 143 weeks of follow-up.Citation10 Women were excluded if weight had not been assessed on at least two occasions. Body mass index was calculated as body weight (kg)/height (m) squared. A whole body densitometry scan was also taken at baselineCitation11 and analyzed by a single radiographer. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM) was calculated from the sum of lean tissue mass for the arms plus the legsCitation11 so that a total skeletal muscle mass could then be determined.Citation12 To ascertain if sarcopenia was present, ASM was adjusted for stature (ASM/height (kg/m2)Citation13 and percentage skeletal muscle was also computed.Citation14 Body composition data from an Australian female reference group provided cutoff values.Citation11

Nutritional intake

Trained dietitians collected 3-day records based on the weighed intake of all foods, beverages, and food supplements taken at main meals plus morning and afternoon tea, with foods weighed to ±1 g on digital scales (Soehnle Venezia, Switzerland). A recall of foods and beverages consumed outside set meal times was also taken. Mean daily intake was calculated using the SERVE Nutrition Management System version 5.0.012, 2004 (Serve Nutrition Systems, St Ives, NSW). Nutrient intakes were compared with the estimated average requirementsCitation15 currently recommended in Australia and New Zealand; the estimated average requirements indicate the amount of a given nutrient needed to meet the requirement of 50% of the healthy individuals in a population of this age.

Blood collection and laboratory analyses

Nonfasting, peripheral venous blood was analyzed for 25 hydroxycholecalciferol and albumin at Network Pathology, Austin Health, Melbourne, as described previously.Citation11 High sensitivity C-reactive protein was also measured using a Beckman Coulter Synchron LX system chemistry analyser, with reagents and calibrators supplied by Beckman Coulter Inc (Sydney, Australia). The proinflammatory cytokine, interleukin-6, was measured by a commercial automated chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay using an Immulite Analyser from Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA. C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and hemoglobin in nonfasting whole blood was measured at Southern Cross Pathology, Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne.

Abbreviated mental test score

One qualified researcher assessed cognition using a modified Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) scored out of 10.Citation16 A cutoff score of 7 or 8 is considered to discriminate between cognitive impairment and normality.Citation16

Muscle strength

Muscle strength was determined by the same experienced technician through measurement of the maximal isometric strength of ankle dorsiflexors, knee extensors, and hip abductors in both legs using a hand-held dynamometer, ie, the Nicholas manual muscle tester (Lafayette Instruments, Lafayette, IN), as described previously.Citation17

Physical function

Physical function was determined by timed up and go (TUG) and walking speed over a 6 m distance, as described previously.Citation17 One technician performed all function tests.

Other covariates

Age (in years) was calculated as the difference between the date of first assessment and the reported date of birth. Comorbidity was defined as the number of current chronic conditions based on medical record reporting of cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, kidney disease, or lung disease. Long-term medications were defined as current medications that were taken to treat a chronic condition. Falls were recorded via a specially designed reporting sheet, providing full fall details including time, activity associated with fall, and outcome of fall. A registered nurse recorded disease conditions and medications from resident medical records maintained at each facility and verified falls data from incident reports.

Outcome data

The decision to move a woman to high care was made by the consulting medical practitioner on the basis of their clinical requirement for additional care. Data relating to participants’ mortality or their transfer to high care were obtained by a registered nurse from medical reports examined every three months throughout the full 143-week follow-up period. A single outcome was recorded for each woman, ie, whether they stayed in low care, moved to high-care, or died.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 19.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago IL). Descriptive data are given as the mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables. Differences between groups were tested using the Student’s t-test for unpaired data. The proportions of women experiencing weight change were examined using frequencies and plots of distribution. Weight loss over 143 weeks was then coded as a single dichotomous variable. Crude assessment of a composite outcome indicative of the end of low-level care (by death or move to high care) was explored using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between levels were tested using the log-rank test. Risk of weight loss on the combined outcome of mortality or transfer to high care was estimated by Cox proportional hazard regression, computing hazard ratios, and 95% confidence intervals. Given the relatively small sample size, only age and a single other covariable were adjusted for in each model explored. The assumption that hazards were proportional was assessed via log-minus-log survival plots.

Results

At baseline, the women in this study were aged 86.2 ± 5.3 years. The youngest was aged 67 years and the oldest 96 years. Although living in low-level care, 38% had cardiovascular disease, 23% had previously experienced a stroke, 9% had lung disease, 8% had renal disease, 8% had diabetes, and 6% had Parkinson’s disease, while 11% had previously had cancer. No women had active cancer as diagnosed by a general practitioner at the time of assessment. The women studied were largely cognitively healthy (mean ATMS score 8.36). Only seven had mild dementia (mean AMTS score 7.1 ± 1.5 in this subgroup), with only two having scores <7. The presence of these medical conditions at baseline was not associated with any measures of body composition, or with indices of sarcopenia, hematological parameters, dietary intake, ATMS score, falls, strength, or physical functioning. However, the presence of medical conditions was mildly and inversely associated with age (r = −0.279, P < 0.04). Women exhibiting none of the listed medical conditions were slightly older than those who had two conditions (88.8 ± 4.3 years versus 84.2 ± 4.3 years, P < 0.05).

During the study, 60% of the women unintentionally lost weight (−4.6 ± 3.6 kg, range 0.5–17.0 kg) while 40% maintained or gained weight (mean weight change +2.6 ± 2.1 kg, P < 0.01). Overall mean weight change for the whole group was −1.85 ± 4.6 kg, P < 0.01. compares the baseline characteristics of the women who remained weight stable with those who lost weight. Although those who lost weight were older (P < 0.05), they did not differ in number of medical conditions, number of medications, number of falls, or ATMS score from those who maintained weight. However, weight losers had a higher initial body mass index (P < 0.01) but exhibited no other differences in weight, body composition, or prevalence of sarcopenia (whether defined in absolute or relative terms). Women who lost weight had significantly higher levels of C-reactive protein (P < 0.05). Although mean interleukin-6 was also higher, the difference was not of statistical significance (). The high body mass index of the weight losers related to their height rather than their adiposity; the weight losers were significantly shorter than the weight maintainers (P < 0.05). Differences in nutritional intake were also evident at baseline when women who subsequently lost weight were consuming less dietary energy (P < 0.05) and obtaining a lower proportion of their estimated energy requirement (P < 0.01). They also consumed less protein relative to body weight (P < 0.01) than those who maintained weight.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics for elderly, institutionalized women who lost weight compared with those who did not lose weight

In addition, the weight losers were less physically able. They exhibited lower hip abductor strength (P < 0.01), slower walking speed (P < 0.01), and a longer TUG (P < 0.05) than the women who maintained weight. They also had lower serum albumin (P < 0.01) and higher C-reactive protein (P < 0.05) than those who maintained weight, although other biochemical markers did not differ.

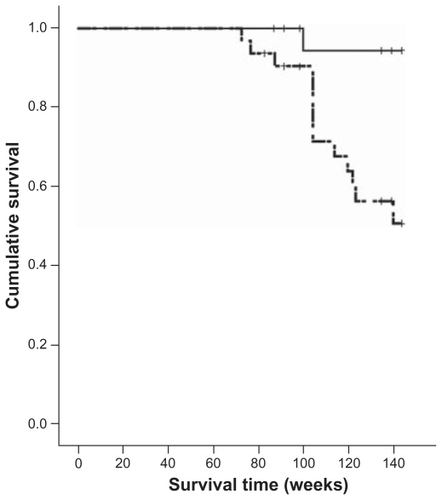

During the 143 weeks of follow-up, only 39 of the initial 53 women (73.6%) remained in low-level care. Seven women died (13.2%) and another seven transferred to high-level care. Mean survival time was 131.9 ± 2.8 weeks (). Those who lost weight were more likely to end their low-level care by death or a move to high care (40.6%) than those who did not lose weight (4.8%, P = 0.01, data not shown).

Table 2 Change in body composition in elderly, institutionalized women and occurrence of death or a move to high care over a period of 143 weeks

presents the body composition changes that took place over the 143-week period, comparing changes in those who lost weight with those who maintained or gained weight. While there was no difference in the loss of lean tissue mass, the weight losers lost significantly more fat mass than the weight maintainers (P < 0.001). Moreover, those who lost weight were lost to low-level care either through death (18.8%) or from transfer to high care (21.9%) significantly earlier (125.9 ± 23.2 weeks) than those who did not experience weight loss (140.8 ± 10.5 weeks, P < 0.01). The difference between these groups equates to 28.4 weeks for those who transferred to high care and 22.6 weeks for those who died. presents a Kaplan-Meier plot comparing the incidence of the composite outcome of death or transfer to high care in the two groups. Little change occurred during the first two years. Thus, after 104 weeks, only four women ended low-level care by death or transfer to high-level care (n = 3 and n = 1, respectively) while 91% of weight losers and 95% of weight maintainers remained in low-level care. However, by 143 weeks, all those who had transferred to high care (100%) and 86% of those who died were weight losers (P = 0.03).

Figure 1 Kaplan-Meier plot comparing the incidence of death or transfer to high-level care in elderly women (n = 53) who experienced weight loss (hatched line) compared with those who experienced no weight loss (solid line) over a 143-week period.

Few associations were evident in unadjusted univariate Cox proportional hazards analysis between measured variables and the composite outcome of death or transfer to high care. Age, body mass index, number of medical conditions and medications, body composition, measures of sarcopenia and C-reactive protein, dietary intake, number of falls, and hip strength were all unrelated to the composite outcome of mortality or transfer to high care (data not shown). The one major association to emerge was with weight loss (hazards ratio 0.095, P = 0.02) which significantly predicted death or transfer to high care (). Adjustment for age or for age plus energy intake (or percent estimated energy requirement) did not alter this relationship. Adjustment for age and hip strength reduced the hazards ratio, as did adjustment for age plus height or age plus albumin. Adjustment for age plus C-reactive protein or age plus TUG had only a small attenuating effect. However, none of these additional variables proved to be a significant predictor in any of the models examined. Weight loss thus remained the best predictor of death or increased disability.

Table 3 Associations between weight loss (reference) and mortality or transfer to high care in elderly, institutionalized women

Discussion

Our findings indicate that in a group of older and mainly cognitively healthy women, those who lost weight had a higher risk of ending their stay in low-level care through mortality or transfer to high care than those who did not lose weight. Moreover, those who experienced weight loss were those whose mean baseline body mass index was within the “overweight” range. These relatively heavy women may possibly be overlooked as having a potentially poor prognosis because it is more common for a low body mass index to alert clinicians to poor nutritional status.Citation1 Our findings suggest that, in this group of older women, any unintentional weight loss, even in those who are overweight, is a cause for concern, needs to be monitored, and should trigger appropriate action from clinicians.

The degree of weight loss experienced by our cohort of aged women in low-level care (−1.85 ± 4.6 kg) resembles that reported over a two-year period in Canadian community-dwelling and institutionalized elderly aged 80–89 years.Citation18 Moreover, our finding of earlier death among those who experienced weight loss is consistent with studies for both elderly remaining in the general communityCitation3–Citation6 and those living in high-level care.Citation7 In the latter case, Canadian elderly who lost > 4.5 kg over two years experienced death earlier than those who either gained weight or whose weight remained stable. A recent report has also indicated that weight loss in the year prior to death is more highly predictive of mortality than weight loss occurring three years earlier.Citation19 Even a moderate degree of unintentional weight loss may thus be an important predictor of earlier death across the continuum of elderly care.

Little has previously been reported on the association between weight loss in the elderly and the necessity for transition into care or into higher levels of care. Rajala et alCitation20 found no relationship between weight loss and transfer of elderly people from the community into an old people’s home. Nevertheless, they also report that elderly with a body mass index ≤ 22 kg/m2, suggestive of weight loss, were more likely to be placed in a long-stay hospital ward.

Weight loss in the elderly has been associated with older age, higher weight, longer TUG time, slower walking speed, lower strength, and greater disability (by activities of daily living).Citation3,Citation21,Citation22 We previously found that hip abductor strength was associated with functional decline in elderly people.Citation17 However, in this present study, hip abductor strength was not associated with mortality or transfer to high care, although those who lost weight had lower hip strength at baseline than weight maintainers. In addition, lean tissue mass and indices of sarcopenia were not associated with mortality or transfer to high care, as reported by others.Citation21,Citation22 The reason why no association was apparent with sarcopenia is unclear. Although prevalence of absolute sarcopenia in the study population was only 9%, the prevalence of relative sarcopenia was 38%, making the explanation of sample bias unlikely in the latter case.

A frequent cause of weight loss in the elderly is a loss of appetite leading to reduced food intake.Citation2 Among Australian women previously studied in low-level care, mean energy intake fell below estimated requirements for 65% of the women surveyed.Citation10 Because the women reported in this study were drawn from the same population, a degree of unintentional weight loss was predictable as a result of this hypocaloric intake. None of the participants was intentionally following a weight reduction diet. Unintentional weight loss,Citation4,Citation23,Citation24 but not the intentional weight loss experienced by obese elderly,Citation25 is associated with increased mortality.

In elderly people, recent rapid weight loss is often associated with underlying illness.Citation19 This can complicate the interpretation of studies in the elderly because it is usually unclear whether the weight loss precipitates or merely reflects the adverse medical condition.Citation26 In the present study, we found no difference in number of diseases (or number of medications) between our groups at baseline, although we did do not report the severity of disease. However, C-reactive protein levels were higher in those who lost weight. High C-reactive protein, as a positive acute phase reactant suggests a proinflammatory state.Citation27 Although not specifically examined here, C-reactive protein and other biomarkers of inflammation may well have utility in signaling the potential for more adverse health outcomes in elderly women.

Changes to body composition may be of equivalent importance as the weight change per se.Citation26 We observed that those who lost weight preserved their lean tissue mass and predominantly lost fat mass, as reported in an earlier study, also in women.Citation28 The adverse effects of this weight loss therefore appear unrelated to the development of sarcopenia but to change in body fat stores. While high body fat has numerous adverse effects,Citation29 moderate levels of obesity in the elderly impart little increase in mortality,Citation29 and accumulation of body fat is associated with the benefits of higher bone mineral density and a slower rate of bone loss.Citation29 However, in the present study, although a strong relationship was evident between bone mineral density and total fat (r = 0.6, P < 0.001), there was no difference in bone mineral density at baseline between those who lost weight and those who did not. Similarly, bone mineral density did not predict death or a move to high care (data not shown).

The cost of providing residential aged care in Australia is increasing. Most of the aged care services budget in 2008/09 ($10,079 billion) went towards the provision of residential aged care ($6654 billion).Citation8 The subsidy per person in high care was $51,550 per annum as compared with only $20,150 per annum for low-level care.Citation9 Preventing or delaying the necessity for transition to high care would therefore result in substantial savings. We observed a time difference of 28.4 weeks, representing a potential saving of $17,149 per person.

This study is limited by the small sample size, the focus on women only, relatively short follow-up, and the use of a convenience sample of volunteer participants. However, methodologies used for data collection of weight, body composition, and other measures of nutritional intake and status are all objectively based. This is also the first study of this kind to report on elderly women residing in low-level care.

The results of this study highlight that weight loss can be a signal for higher morbidity and mortality that requires clinical investigation so that interventions to treat underlying causes and to reverse or prevent weight loss can be implemented. They also demonstrate the need for effective weight monitoring in low-level care residents. The accreditation standards for residential care in AustraliaCitation30 require that facilities demonstrate that residents receive adequate nutrition and hydration. Although one expected outcome should be regular weight monitoring of residents, little definitive advice has been provided on frequency of weight measurement or outlining the clinical response needed when a substantive weight change is noted. A more operationalized approach is called for before savings associated with weight loss prevention and delayed transfer to high care can be realized. Where weight loss is identified, there is a need to investigate the causative factors, treat any medical problems, and make changes to the dietary intake to coincide with resident needs. This may require provision of high energy supplements, ie, the addition of higher kilojoule ingredients to regular foods, eg, cream, oil, and sugar, modification of the texture of food so that it can be eaten more readily, and/or increasing physical and social support with eating, which have recently been shown to assist with weight gain and potentially with functional status.Citation31

Further research is required to investigate the adverse outcomes of weight loss in low-level care residents more fully (including studies in men) and to develop guidelines for those responsible for care so that measures to prevent weight loss can be established.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank staff and residents of the aged care facilities for their cooperation and participation in the study. We would also like to acknowledge research nurses, Sheila Matthews, Judy Tan, and Kylie King, who sourced medical data on residents, and Bereha Khorda for performing muscle strength and functional testing. The larger trial in which this study was nested was funded by Dairy Australia.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MillerSWolfeRThe danger of weight loss in the elderlyJ Nutr Health Aging20081248749118615231

- BalesCWRitchieCSSarcopenia, weight loss, and nutritional frailty in the elderlyAnn Rev Nutr20022230932312055348

- NewmanABYanezDHarrisTBWeight change in old age and its association with mortalityJ Am Geriatr Soc2001491309131811890489

- LocherJLRothDLRitchieCSBody mass index, weight loss, and mortality in community-dwelling older adultsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2007621389139218166690

- WedickNMBarrett-ConnorEKnokeJDWingardDLThe relationship between weight loss and all-cause mortality in older men and women with and without diabetes mellitus: The Rancho Bernardo StudyJ Am Geriatr Soc2002501810181512410899

- ReynoldsMFredmanLLangenbergPMagazinerJWeight, weight change and mortality in a random sample of older community dwelling womenJ Am Geriatr Soc1999471409141410591233

- DwyerJTColemanKAKrallEChanges in relative weight among institutionalized elderly adultsJ Gerontol1987422462513571859

- Australian Institute of Health and WelfareResidential Aged Care in Australia 2008–2009A Statistical OverviewCanberra, AustraliaAustralian Institute of Health and Welfare2010

- Department of Health and AgeingReport on the Operation of the Aged Care Act 1997: 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2010Canberra, AustraliaAustralian Government Printer2009

- WoodsJLWalkerKZIuliano-BurnsSStraussBJMalnutrition on the menu: nutritional status of institutionalised elderly Australians in low-level careJ Nutr Health Aging20091369369819657552

- HeymsfieldSBSmithRAuletMAppendicular skeletal muscle mass: measurement by dual-photon absorptiometryAm J Clin Nutr1990522142182375286

- KimJWangZHeymsfieldSBTotal-body skeletal muscle mass: estimation by a new dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry methodAm J Clin Nutr20027637838312145010

- BaumgartnerRNKoehlerKMGallagherDEpidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New MexicoAm J Epidemiol19981477557639554417

- JanssenIHeymsfieldSBRossRLow relative skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia) in older persons is associated with functional impairment and physical disabilityJ Am Geriatr Soc20025088989612028177

- Department of Health and Ageing, National Health and Medical Research CouncilNutrient Reference Values for Australia and New ZealandCanberra, AustraliaAustralian Government Printer2006

- HodkinsonHEvaluation of a mental test score for assessment of mental impairment in the elderlyAge Ageing197412332384669880

- WoodsJLIuliano-BurnsSKingSJPoor physical function in elderly women in low-level aged care is related to muscle strength rather than to measures of sarcopeniaClin Interv Aging20116677621472094

- ShatensteinBKergoatM-JNadonSAnthropometric changes over 5 years in elderly Canadians by age, gender, and cognitive statusJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200156M48348811487600

- BamiaCHalkjærJLagiouPWeight change in later life and risk of death amongst the elderly: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Elderly Network on Ageing and Health studyJ Int Med2010268133144

- RajalaSAKantoAJHaavistoMVBody weight and the threeyear prognosis in very old peopleInt J Obes19901499710032086502

- NewmanABKupelianVVisserMStrength, but not muscle mass, is associated with mortality in the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study CohortJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci20066727716456196

- CesariMPahorMLauretaniFSkeletal muscle and mortality results from the InCHIANTI StudyJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200964A37738419181709

- FrenchSAFolsomARJefferyRWWilliamsonDFProspective study of intentionality of weight loss and mortality in older women: The lowa Women’s Health StudyAm J Epidemiol199914950451410084239

- KnudtsonMDKleinBEKKleinRShankarAAssociations with weight loss and subsequent mortality riskAnn Epidemiol20051548349116029840

- SheaMKHoustonDKNicklasBJThe effect of randomization to weight loss on total mortality in older overweight and obese adults: The ADAPT StudyJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci201065A51952520080875

- RichmanELStampferMJWeight loss and mortality in the elderly: separating cause and effectJ Int Med2010268103105

- PadayacheeLRodsethRNBiccardBMA meta-analysis of the utility of C-reactive protein in predicting early, intermediate-term and long term mortality and major adverse cardiac events in vascular surgical patientsAnaesthesia20096441642419317708

- NewmanABLeeJSVisserMWeight change and the conservation of lean mass in old age: the Health, Aging and Body Composition StudyAm J Clin Nutr20058287287816210719

- VillarealDTApovianCMKushnerRFKleinSObesity in older adults: technical review and position statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity SocietyAm J Clin Nutr20058292393416280421

- Office of Legislative Drafting and PublishingQuality of Care Principles 1997Canberra, AustraliaThe Attorney-General’s Department2010

- BeckAMWijnhovenHAHLassenKOA review of the effect of oral nutrition interventions on both weight change and functional outcomes in older nursing home residentse-SPEN, Eur e-J Clin Nutr Metab20116e101e105