Abstract

Background

Visual impairment is more prevalent in the elderly and depression is common in this population. Although many studies have investigated depression or quality of life (QOL) in older adults with visual impairment, few have looked at the association between these two concepts for this population. The aim of this systematized review was to describe the association between depression and QOL in older adults with visual impairment.

Methods

A search was done using multiple electronic databases for studies addressing the relationship between QOL and depression in elders with visual impairment. The concept of QOL was divided into two different approaches, ie, QOL as achievement and QOL as subjective well-being. Comparison of QOL scores between participants with and without depression (Cohen’s d) and correlations between depression and QOL (Pearson’s r) were examined.

Results

Thirteen studies reported in 18 articles were included in the review. Nearly all of the studies revealed that better QOL was moderately to strongly correlated with less severe depressive symptoms (r = 0.22–0.68 for QOL as achievement; r = 0.68 and 0.72 for QOL as subjective well-being). Effect sizes for the QOL differences between the groups with and without depression ranged from small to large (d = 0.17 to 0.95 for QOL as achievement; no data for QOL as subjective well-being).

Conclusion

Additional studies are necessary to pinpoint further the determinants and mediators of this relationship. Considering the high prevalence rate of depression in this community and its disabling effects on QOL, interventions to prevent and treat depression are essential. More efforts are needed in clinical settings to train health care practitioners to identify depressed elders with visual impairment and provide appropriate treatment.

Introduction

The prevalence of vision loss in the elderly is high, being about 15% for people aged 65 years and older and up to 30% in people 75 years and over.Citation1–Citation4 The onset of visual impairment in later life alters life habits and has various consequences. For example, older people with visual impairment present more restrictions in participation than their peers,Citation5,Citation6 have less social interaction,Citation1,Citation7–Citation9 feel lonelier,Citation10,Citation11 and are at risk of developing depressive symptoms.Citation12–Citation15 In the literature, there is strong evidence that visual impairment is related to depression. Consideration should be given to how depression affects the quality of life (QOL) of older adults with visual impairment.

Historically, the success of health interventions has been evaluated from an outsider perspective, using tests focusing on observable life conditions or physical functioning. Over the last two decades, evaluation of outcomes by the patient, giving the insider perspective, has become increasingly popular. In this new paradigm, it is important to assess QOL when evaluating health research and interventions.

Despite its popularity, there is still no consensus about the conceptualization of QOL, apart from an agreement that it is multidimensional, personal, should primarily be evaluated subjectively, and can vary over time. Some authors consider that this concept incorporates two major approaches, ie, QOL as achievement and QOL as subjective well-being.Citation16–Citation18 QOL as achievement refers principally to the person’s functional status. It mainly assesses the capacity, as perceived by the individual him/herself, to do a particular activity, such as reading, dressing, or walking, as well as to take care of basic needs to stay healthy and assume social roles. Usually, the tools used to evaluate this aspect of QOL do not allow for any modulation based on the person’s perspective or goals. Health-related QOL is a major category of QOL as achievement. QOL as subjective well-being, which will be referred to as subjective QOL in this paper, represents mostly the sum of the cognitive and emotional reactions describing the person’s satisfaction with life and well-being in relation to his/her goals, expectations, concerns, values, and priorities. Subjective QOL evaluation depends mainly on the congruence or discrepancy between the person’s achievements and expectations. It tends to reflect a more global aspect of QOL. The instruments used to assess subjective QOL aim to understand the way individuals perceive their condition according to their values and expectations.

QOL can be seriously affected by vision loss. In fact, visual impairment is a very disabling condition, especially when it is acquired in later life.Citation19–Citation21 A study by Brown et al found that severe age-related macular degeneration affects QOL in a way that is comparable with advanced prostate cancer, with unmanageable pain along with bladder and sexual dysfunction, or with a severe stroke leading to constant nursing care, incontinence, and paralysis.Citation22 The burden of vision loss is substantial and its consequences are numerous, from functional to social and psychological, and it can lead to depression.Citation23,Citation24 The prevalence of major depression in older adults with visual impairment is estimated to be around 14%,Citation25 while depressive symptoms affect about one third of elders with visual impairment.Citation15,Citation24,Citation26 In turn, depression affects elders’ QOL.Citation27

Previous studies have shown that older adults with clinically significant depressive symptoms have worse health-related QOL and greater disability over time.Citation28 Characteristics of depression include aversion to activities previously enjoyed, lack of stamina, and poor concentration.Citation29 Depressive symptoms therefore contribute to the “disablement process speeding up disease to disability”.Citation30 This is particularly true with visual impairment, since daily tasks require a great deal of concentration and effort.

Even though medicine has made important advances in the treatment of age-related eye diseases in recent years, many patients still suffer from noncorrectable vision loss.Citation21 With an aging population in developed countries, the number of older people with visual disabilities is expected to increase substantially in the years to come.Citation31,Citation32 Knowing that visual impairment is more prevalent in the elderly and that depression is common in this population, it is important to look at the impact of depressive symptoms on older people’s QOL. Although many studies have investigated depression or QOL of older adults with visual impairment, few have looked at the association between these two concepts for this population. The aim of this systematized review was to describe the association between depression and QOL in older adults with visual impairment.

Materials and methods

Literature search strategy

A search of the literature was done using multiple databases, ie, MEDLINE, PsychInfo, Pubmed, EMBASE, Social Work Abstracts, and Cochrane. An attempt was made to find gray literature via Google Scholar and proceedings of international scientific meetings. Bibliographies of articles were searched manually for additional studies. The terms mapped were visual conditions such as “visual impairment”, “macular degeneration”, or “glaucoma” associated with depression terms such as “depressive disorder” or “depressive symptoms” and QOL terms such as “life satisfaction”, “well-being”, or “quality of life”. The research was limited to elders and studies were manually sorted to keep only those with older participants (>55 years) having visual impairment. Visual impairment was defined as any eye disease causing a noncorrectable decrease in vision that corresponds to a visual acuity of 6/12 (20/40) or less or a visual field of 60° or less in the better eye. Self-reported visual impairment was included if participants were receiving services from a vision rehabilitation agency. All types of study design were included except case reports. Reviews and meta-analyses were not analyzed but were used to find more relevant articles. The search was limited to literature from 1980 to June 1, 2012 in English or French. EndNote X5 (Thomson Reuters X5.0.1, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to manage the database.

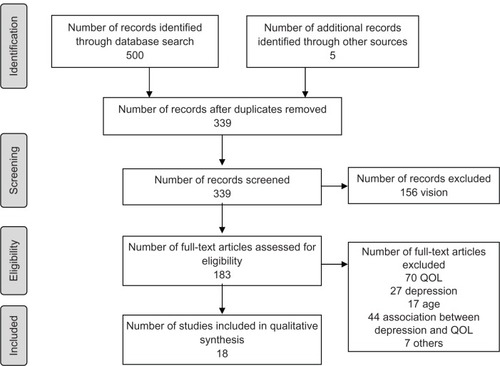

A total of 339 articles were found using the database search. This number was reduced to 18 after reading the abstracts or complete articles (see ). Most studies were removed because the analysis did not look at the association between depression and quality of life, or the majority of the sample did not suffer from visual impairment. Questionnaires had to assess QOL as perceived by the individual (patient-reported outcomes).

Evaluation of methodological quality of studies

There are numerous tools available to assess the methodological quality of studies.Citation33 Critical elements considered (eg, susceptibility to bias, confounding as well as the number and weighting of items) can vary widely among tools. Thus, evaluation of a study with different tools can result in different levels of quality. We choose the Cho and Bero scale because it allows assessment of experimental as well as observational studies.Citation34 Also, its development has been documented, and its validity and reliability have been previously tested.Citation34 Both authors read all the articles and independently assessed the methodological quality of each study using this 24-item scale. The score was calculated as a fraction of the total score out of the number of items applicable. Thus, the total score varied between 0 and 1, with higher scores indicating better methodological quality. For the purpose of the analysis, the calculated score was used to qualify a study as excellent (score >0.85), good (0.70–0.85), fair (0.55–0.69), or poor (<0.55). Studies where there were discrepancies between the reviewers’ scores were re-evaluated and discussed to decide the final score. The score for the studies included in the review fluctuated between 0.62 (fair) and 0.77 (good); none achieved a perfect score, mainly because of study design, measurement bias, or confidence intervals not being reported. Studies with very poor methodological quality (Cho score <0.35) were excluded.

Studies were classified according to the study level. The classification used was as follows: randomized controlled trial (I), cohort (II), case control (III), and case series (IV).Citation35

Data extraction

Characteristics of the population, study design, type of questionnaire, and relevant outcomes were extracted. Data were collected systematically for every correlation (Pearson’s r), odds ratio and variance related to the association between depression and QOL, QOL comparison data between groups with and without depression (mean and standard deviation), and prevalence of depression. The strength of a correlation was assessed using Cohen’s scaleCitation36 in which a correlation, in absolute value, of ≥0.5 was qualified as a strong association, from 0.3 to 0.49 as moderate, from 0.1 to 0.29 as weak, and ≤0.09 as no correlation. For the comparison between two means concerning QOL, Cohen’s d was calculated to give a standardized mean effect size when the mean and standard deviation of the group with depressive symptoms and the group without depressive symptoms were provided. A d = 0.2, in absolute value, was considered to be a small effect size, 0.5 a medium effect size, and 0.8 a large effect size.Citation36 No meta-analysis was conducted because the studies were too dissimilar, among other things, in methodology, measuring tools, or accounting for confounding factors.

After reading the papers in detail, we realized that some described the same sample and were based on the same project. After discussion, we agreed to aggregate the results of these multiple papers depicting the same project and consider them as a single study.Citation15,Citation20,Citation24,Citation37–Citation43 Therefore, 13 studies (11 observational and two interventional) reported in 18 papers were included in this review.

Results

Studies included in the review

Thirteen studies (18 articles) addressing the relationship between depression and QOL were selected. Five of the studies were cross-sectional (IV), one was a case-control (III) study, and seven were follow-up studies (II). There were no randomized clinical trials (I). The follow-up time ranged from six to 48 months. Most of the studies originated in the United States (n = 9) while the others were conducted in Australia (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1), or the United Kingdom (n = 1). Eight of the American studies were generated by two different research groups: one team headed by Horowitz and Reinhardt was from a vision rehabilitation agency in New York, and the other group directed by Rovner was based at an ophthalmological hospital in Philadelphia. Although the focus of most of the selected studies was not the association between depressive symptoms and QOL, Rovner et al were directly interested in the effect of depression on functional disability (health-related and vision-related QOL).

The study populations came primarily from low vision rehabilitation agencies or specialized ophthalmology clinics. The sample size varied greatly, ranging from 31 to 438 participants. For the majority, the population was very old, with a mean age varying from 77 to 84 years. The visual impairment was recent in most of the studies and was the result of age-related eye diseases without any distinction (eight studies) or was limited to one disease in particular, more specifically age-related macular degeneration (five studies).

Five different instruments were used to measure depressive symptoms (see ); the prevalence of significant depressive symptomatology ranged from 29.4% to 43.4%Citation13,Citation14,Citation20,Citation24,Citation39,Citation40,Citation42,Citation44 (see ). Three studies assessed depressive disorders by clinical interview according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria or using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV); the prevalence varied between 7.2% and 38.6%.Citation15,Citation38,Citation45 Although half of the studies assessed the relationship between depression and both health-related and vision-related QOL (n = 7), some investigated only the association with either health-related (n = 2) or vision-related (n = 4) QOL. Only two studies looked at the association between depression and subjective QOL.

Table 1 Prevalence of depression in the selected studies

Outcomes of interest

To evaluate the relationship between depression and QOL, we focused on two main elements, ie, QOL comparisons between participants with and without depressive symptoms (mean ± standard deviation, Cohen’s d), and correlations between depression and QOL (Pearson’s r) (see ). The outcomes are discussed in three main sections, ie, depression and health-related QOL, depression and vision-related QOL, and depression and subjective QOL. The first section, health-related QOL, includes generic instruments measuring essentially the person’s functional limitations related to health status. The second section, vision-related QOL, includes vision-specific tools. These questionnaires assessing mainly difficulty in vision-related activities aim to determine the impact of vision loss on QOL as perceived by the individual. Health-related and vision-related QOL are both included in QOL as achievement. The third section presents the studies which assessed subjective QOL.

Table 2 Description of the selected studies

Depression and health-related QOL

In the studies included in this review, four different tools were used to assess general health-related QOL (number of studies): Community Disability ScaleCitation46 (n = 2), Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health SurveyCitation47 (SF-36, n = 2), Older Americans Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment QuestionnaireCitation48 (n = 4), and Sickness Impact ProfileCitation49 (n = 1).

Two studies by Reinhardt et al using the Older Americans Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire showed a significant moderate association between health-related QOL and depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults with visual impairment recruited at a low vision rehabilitation agency.Citation37,Citation50 Using the same questionnaire, in two longitudinal studies, Horowitz et al also found a weak to moderate significant association for elders with visual impairment seeking rehabilitation services.Citation15,Citation39–Citation41 In their study of 438 elders with visual impairment, participants with subthreshold depression or depression had significantly lower health-related QOL than nondepressed participants (medium to large effect size).

The most widely known health-related QOL questionnaire, the SF-36, is divided into two components, physical and mental health, each including four domains. The two studies using that tool showed that more depressive symptoms were significantly related to worse health-related QOL.Citation13,Citation44 In a study by Mathew et al,Citation13 the associations in all the physical health domains were moderate except for one, which was strong, while the correlations were strong for all the mental health domains. Therefore, the mental component of the SF-36 had a stronger correlation with depressive symptoms than the physical component in this Australian study. In a study by Hayman et al, participants with significant depressive symptoms presented lower scores than nondepressed participants for the different SF-36 subscales (medium effect size for the physical component, and large effect size for the mental component); the standardized difference between the two groups was larger for the mental component than for the physical component.Citation44 Fewer depressive symptoms were also significantly related to better health-related QOL.Citation44

The two follow-up studies by Rovner et al showed that older adults with visual impairment and significant depressive symptoms had significantly greater disability (poorer health-related QOL) than nondepressed elders (medium effect size) using the Community Disability Scale.Citation24,Citation42 In addition, more depressive symptoms were significantly associated with greater disability, and the strength of the association varied from moderate to strong. In their study of 70 elders with visual impairment at baseline, regression analysis showed that depressive symptoms alone explained 20% of health-related QOL, while the severity of visual impairment explained an additional 7%.Citation38 In the group of participants who completed the study (n = 31), 10 of the 12 who initially had significant depressive symptoms remained depressed two years later; these authors concluded that depressive symptoms left untreated are persistent in this population.Citation24

Brody et alCitation45 used the 68-item Sickness Impact Profile version in their study. Participants with depression had greater disability than nondepressed participants (large effect size). The results also pointed to a significant strong correlation between depressive symptoms and health-related QOL.

In sum, all the studies showed a significant association between fewer depressive symptoms and better general health-related QOL. The strength of the correlations was moderate to strong, varying from 0.23 to 0.68, with a median of 0.43. Four studies found a statistically significant health-related QOL difference between the group with depressive symptomatology and the group without. In addition, Cohen’s d effect size values were medium to large, varying from 0.49 to 0.95, with a median of 0.78.

Depression and vision-related QOL

Vision-related QOL was assessed using five different instruments (number of studies): Activity InventoryCitation51 (n = 1), Functional Vision Screening QuestionnaireCitation52 (n = 5), National Eye Institute Visual Function QuestionnaireCitation53 (NEI-VFQ, n = 4), Sickness Impact Profile specific to visionCitation54 (n = 1), and Visual Functioning IndexCitation55 (n = 1).

Four of the five studies using the Functional Vision Screening Questionnaire found a significant association between more depressive symptoms and worse vision-related QOL; three of these associations were weakCitation37,Citation40,Citation50 while one was moderate.Citation42 This last study, which included 51 older adults with age-related macular degeneration, revealed significantly poorer vision-related QOL for participants with significant depressive symptoms compared with nondepressed participants (medium effect size).Citation42 In this same paper, variation in the depressive symptoms score was related to variation in the vision-related QOL score over a six-month period, and the incidence of significant depressive symptomatology was a significant determinant of decline in vision-related QOL. Further, participants who developed significant depressive symptoms at six months were 8.3 times more likely to experience a decline in their vision-related QOL than those who did not (P = 0.04).Citation43 Conversely, a study of 584 elders with visual impairment seeking rehabilitation services did not find an association between depressive symptoms and vision-related QOL or any statistically significant difference in the Functional Vision Screening Questionnaire score between participants with major depression (n = 42), subthreshold depression (n = 157), or no depression (n = 385, small effect size).Citation41

In the vision domain, the NEI-VFQ is one of the tools most widely used to assess vision-related QOL. In this review, three of the four studies using the NEI-VFQ concluded that a significant association exists between more severe depressive symptoms and worse vision-related QOL,Citation14,Citation45,Citation56 while one found a trend.Citation57 Two studies revealed a strong correlationCitation14,Citation45 and one found a weak correlation.Citation56 The exclusion of individuals with depressive disorders might explain the weaker correlation in the last study. As well, the small percentage of elders with significant depressive symptoms (12.9%) might explain why Rovner et al only found a tendency toward statistical significance in their cross-sectional study.Citation57 The fact that they took into account only the near vision subscale of the NEI-VFQ, which contains items like reading ordinary print in newspapers or difficulty seeing well up close, such as when cooking or sewing, could be another explanation. Including more social and psychological subscales of the NEI-VFQ, such as social functioning, mental health, role difficulties, or dependency, could have resulted in a stronger and statistically significant correlation. In one of these studies, the group with depressive disorders (SCID-IV) had worse vision-related QOL than the group without depression.Citation45 Further, Rovner et al indicated that participants with minimal depressive symptoms, who would not be considered as having significant depressive symptomatology according to usual standards, had worse vision-related QOL than nondepressed participants (medium effect size).Citation56 After they controlled for age, gender, visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and comorbidity, minimal depressive symptoms alone explained 4% of the variance in vision-related QOL (P = 0.001).

In addition, Brody et al measured vision-related QOL using the vision-specific Sickness Impact Profile. Their results indicated that participants with depressive disorders (SCID-IV) had more vision disability than those without depression (medium effect size), and that more depressive symptoms were significantly related to greater vision disability (poorer vision-related QOL).Citation45

One paper by Hayman et al evaluated the association between vision-related QOL, measured using the Visual Functioning Index, and depression in a sample of 391 elders with visual impairment in New Zealand.Citation44 The results emphasized the difference in vision disability between participants with significant depressive symptomatology and nondepressed ones (medium effect size). The group with depressive symptoms presented greater visual disability but the two groups did not differ on visual acuity.Citation44 This study also showed a significant association between fewer depressive symptoms and better vision-related QOL.

The Activity Inventory is another vision-related QOL questionnaire but in this case the individual has to rate the importance of each activity according to his/her lifestyle. Using that tool, Tabrett and Latham found that depressive symptoms had a strong correlation with vision-related QOL in a sample of 100 participants with recent visual impairment.Citation58

In sum, nine studiesCitation14,Citation37,Citation40,Citation42,Citation44,Citation45,Citation50,Citation56,Citation58 showed a significant correlation between depressive symptoms and vision-related QOL; the correlation coefficients varied from 0.22 and 0.64, with a median of 0.31. One study found a trendCitation57 and one revealed no association.Citation41 There was a vision-related QOL difference between the depressed group and the nondepressed group in five studies.Citation41,Citation42,Citation44,Citation45,Citation56 The Cohen’s d were small to large, varying from 0.17 to 0.87, with a median of 0.61.

Depression and subjective QOL

In the vision domain, few studies have assessed subjective QOL in older adults. Only two papers in this review investigated the relationship between depressive symptoms and subjective QOL.Citation14,Citation50 One used the Life Satisfaction Index-ACitation59 and the other used the Quality of Life Index.Citation60

Reinhardt used the 18-item Life Satisfaction Index-A versionCitation61 to assess satisfaction with life in 241 older adults with visual impairment.Citation50 She found a very strong association between fewer depressive symptoms and better subjective QOL.

The Quality of Life Index, frequently used with elders, assesses satisfaction with and the importance of different aspects of life. Satisfaction with life scores are weighted by importance scores. In the Canadian study using this instrument, depressive mood was strongly related with poorer subjective QOL in 64 elders with visual impairment seeking rehabilitation services.Citation14 In that sample, depressive symptoms explained 45% of the subjective QOL score (P < 0.001).

In sum, the two studies showed a very strong significant correlation between depressive symptoms and subjective QOL, Pearson’s r being −0.68 and −0.72.

Discussion

Prevalence of depression

As revealed by the reviewed studies, the prevalence of depressive mood in elders with visual impairment is high, ranging from 7% to 39% for clinical depressionCitation15,Citation38,Citation45,Citation57 and from 29% to 43% for significant depressive symptoms.Citation13,Citation14,Citation20,Citation24,Citation39,Citation40,Citation42,Citation44 In comparison, it is estimated that 5%–8% of community-dwelling elders have depression, and somewhere between 13% and 27% have depressive symptoms.Citation62–Citation65 These troubling rates in older adults with visual impairment are often unsuspected or not well known in primary care and by vision professionals like ophthalmologists and optometrists. Although the high prevalence of depression is more likely to be recognized by low vision rehabilitation specialists, they often do not address this important mental disorder or offer the client appropriate treatment for it. Yet depressive symptoms can have significant effects. Depressed elders left without proper treatment may experience serious consequences, including increased disability, malnutrition, institutionalization, and even mortality.Citation10,Citation66–Citation71 In addition, depressed elders tend to underestimate their functional capacities,Citation72,Citation73 leading to activity restrictions. This decrease in perceived functional status also seems to be present in the older adults with visual impairment. In fact, six studies found that older adults with visual impairment who had depression disorders, significant depressive symptoms, or even minimal depressive symptoms had significantly lower health-related and vision-related QOL than nondepressed elders with visual impairment.Citation24,Citation41,Citation42,Citation44,Citation45,Citation56

Depression, and health-related and vision-related QOL

Nearly all of the articles examined in this review revealed that lower health-related or vision-related QOL was associated with greater symptoms of depression. This significant relationship between depressive symptoms and health-related or vision-related QOL is not surprising. The effect of depression on functional disability and vice versa has been well established for community-dwelling elders.Citation66,Citation74–Citation76 In a community-based study including almost 7000 participants, depression was positively associated with four times more risk of disability.Citation77 Also, a six-year prospective study of community-dwelling depressed elders found an increase in functional limitation over time.Citation78 Conversely, previous studies demonstrated that a reduction in function increases the risk of depressive mood.Citation79

Most studies in this review had a cross-sectional design and therefore could not determine if depression caused an increase in perceived functional disability or if functional disability led to depression. In other words, the change in perceived function is related to increased depressive symptoms, but a cause-and-effect relationship has not yet been established in individuals with visual impairment. However, one longitudinal study of older adults with visual impairment newly enrolled for low vision services showed that greater disability at baseline was a significant predictor of depressive symptoms at six months, after controlling for baseline depressive symptoms and sociodemographic factors, while the opposite was not true.Citation41 This suggests that disability would be a risk factor for depression in this population. On the other hand, incident depressive symptoms were a significant correlate of vision-related QOL decline in a six-month follow-up study of elders with age-related macular degeneration.Citation42 Now that the significant correlation between these two variables has been clearly described, more research is needed to assess which comes first and to pinpoint the determinants and mediators of this relationship. For the majority of studies, the impact of depressive symptoms on QOL was not their purpose, so almost no attempt was made to explain the relationship between those two variables. On the other hand, Rovner et al were specifically interested in that relationship and found that the personality trait of neuroticism was a risk factor for depression. More studies are essential to understand better the relationship between depression and QOL of elders with visual impairment.

It is important to mention that a dichotomy can exist between self-reported measures and objective testing. In clinical settings, this reality is particularly important because the objective performance of a person with visual impairment (eg, being able to read newspaper print, having good reading speed) is not a guarantee that the person is happy with his/her vision or has good QOL. In fact, some studies in this review showed worse vision-related QOL for depressed elders with visual impairment compared with their nondepressed counterparts, but no significant difference in visual acuity between the two groups.Citation24,Citation44,Citation56 Moreover, in a follow-up study of older adults with newly bilateral age-related macular degeneration, a decrease in vision-related QOL (perceived functional vision) was significantly associated with an increase in depressive symptoms, independent of a change in visual acuity (visual function).Citation42 Some authors also maintain that the discrepancy between subjective difficulties and objective function could be a warning sign of depression because individuals with depression tend to underestimate their executive performance and have lower QOL.Citation12,Citation73,Citation80

Depression and subjective QOL

While health-related and vision-related QOL questionnaires address mainly performance, subjective QOL approaches try to understand the more comprehensive aspects of QOL.Citation17 The two studies looking at the association between depressive symptoms and subjective QOL highlighted strong correlations.Citation14,Citation50 In one of these studies, almost half of the subjective QOL was explained by depressive symptoms alone.Citation14 Since depression and subjective QOL both rely on feelings or perceptions, there might be an overlap that explains the strong correlation found. It has already been suggested that these two concepts, depression and subjective QOL, are somewhat similar.

So far we have looked at the relationship between QOL and depression in elders. Fortunately, treatment of depression by medication and psychotherapy in community-dwelling elders has been shown to improve perceived function.Citation81,Citation82 Also, studies which examined treatment of depression by self-management or problem-solving programs have shown that focusing on ways to deal with life differently can help to decrease emotional distress and increase QOL.Citation27,Citation83,Citation84 There is also evidence that self-management programsCitation85–Citation89 and pharmacological treatmentCitation90 can reduce depressive symptoms in elders with visual impairment. Studies also showed the feasibility of delivering self-management or problem-solving programs in usual vision service facilities.Citation85,Citation87,Citation91,Citation92 Implementing such programs in vision clinics and low vision rehabilitation centers could be beneficial for elders with visual impairment. However, further research is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of such interventions and whether pharmacological treatment should be given in conjunction with psychological services.

In order to treat depression, first it has to be diagnosed. As already mentioned, late-life depression in individuals with visual impairment is often unrecognized and untreated.Citation93 It is not just older adults with visual impairment who are undiagnosed but the elderly population in general.Citation94–Citation97 Some efforts have been made to implement collaborative depression management models for the elderlyCitation98–Citation100 but there is still a lot to do. Unless the patient directly tells the clinician that he/she has depressive symptoms, the professional has to search for the signs and symptoms. However, it is easier to blame the ocular disease for poor reading performance than to look for depression. Also, it requires trained professionals who know what to look for in depression.Citation101 In addition, referring patients to the right services and defining professional/personal responsibilities are among the problems to be resolved.Citation93 A program addressing depression issues with health care professionals, with the goal of improving the detection and management of depressive elders with visual impairment, has been developed.Citation102 A lot of sensitization remains to be done in geriatric services.

Conclusion

This review highlighted the association between more severe depressive symptoms and worse QOL in older adults with visual impairment. Additional studies are necessary to pinpoint further the determinants and mediators of this relationship. Considering the high prevalence of depression in this community and its disabling effects on QOL, interventions to prevent and treat depression are essential. More efforts are needed in clinical settings to train health care practitioners to identify depressed elders with visual impairment and provide appropriate treatment.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WallhagenMIStrawbridgeWJShemaSJKurataJKaplanGAComparative impact of hearing and vision impairment on subsequent functioningJ Am Geriatr Soc20014981086109211555071

- The Lighthouse IncThe Lighthouse National Survey on Vision Loss: the experience, attitudes, and knowledge of middle-aged and older Americans1995 Available from: http://www.lighthouse.org/research/archived-studies/national-survey/Accessed August 1, 2012

- CrewsJECampbellVAHealth conditions, activity limitations, and participation restrictions among older people with visual impairmentJ Vis Impair Blind2001958453467

- HorowitzABReinhardtMJoannPPrevalence and risk factors for self-reported visual impairment among middle-aged and older adultsRes Aging200527307326

- DesrosiersJWanet-DefalqueMCTemisjianKParticipation in daily activities and social roles of older adults with visual impairmentDisabil Rehabil200931151227123419802927

- AlmaMAvan der MeiSFMelis-DankersBJvan TilburgTGGroothoffJWSuurmeijerTPParticipation of the elderly after vision lossDisabil Rehabil2011331637220518624

- CookGBrown-WilsonCForteDThe impact of sensory impairment on social interaction between residents in care homesInt J Older People Nurs20061421622420925766

- DefiniJBurack-WeissAPsychosocial assessment of adults with vision impairmentsSilverstoneBLangMARosenthalBPFayesEThe Lighthouse Handbook on Vision Impairment and Vision Rehabilitation2New York, NYOxford University Press2000

- CabreraMAMesasAEGarciaARde AndradeSMMalnutrition and depression among community-dwelling elderly peopleJ Am Med Dir Assoc20078958258417998114

- YoshimuraKYamadaMKajiwaraYNishiguchiSAoyamaTRelationship between depression and risk of malnutrition among community-dwelling young-old and old-old elderly peopleAging Ment Health201317445646023176659

- VerstratenPFJBrinkmannWLJHStevensNLSchoutenJSAGLoneliness, adaptation to vision impairment, social support and depression among visually impaired elderlyInt Congr Ser200512820317321

- CastenRRovnerBDepression in age-related macular degenerationJ Vis Impair Blind20081021059159920011131

- MathewRSDelbaereKLordSRBeaumontPVaeganMadiganMCDepressive symptoms and quality of life in people with age-related macular degenerationOphthalmic Physiol Opt201131437538021679317

- RenaudJLevasseurMGressetJHealth-related and subjective quality of life of older adults with visual impairmentDisabil Rehabil2010321189990719860601

- HorowitzAReinhardtJPKennedyGJMajor and subthreshold depression among older adults seeking vision rehabilitation servicesAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200513318018715728748

- DijkersMPQuality of life of individuals with spinal cord injury: a review of conceptualization, measurement, and research findingsJ Rehabil Res Dev2005423 Suppl 18711016195966

- HaasBKClarification and integration of similar quality of life conceptsImage J Nurs Sch199931321522010528449

- LevasseurMTribbleDS-CDesrosiersJAnalysis of quality of life concept in the context of older adults with physical disabilitiesCan J Occup Ther2006733163177 French16871858

- TielschJMSommerAWittKKatzJRoyallRMBlindness and visual impairment in an American urban population: the Baltimore Eye SurveyArch Ophthalmol199010822862902271016

- ReinhardtJPEffects of positive and negative support received and provided on adaptation to chronic visual impairmentAppl Dev Sci2001527685

- HooperPJutaiJWStrongGRussell-MindaEAge-related macular degeneration and low-vision rehabilitation: a systematic reviewCan J Ophthalmol200843218018718347620

- BrownGCBrownMMSharmaSThe burden of age-related macular degeneration: a value-based medicine analysisTrans Am Ophthalmol Soc200510317318417057801

- SilverstoneBLangMRosenthalBFayeEEThe Lighthouse Handbook on Vision Impairment and Vision RehabilitationIINew York, NYOxford University Press2000

- RovnerBWZisselmanPMShmuely-DulitzkiYDepression and disability in older people with impaired vision: a follow-up studyJ Am Geriatr Soc19964421811848576509

- EvansJRFletcherAEWormaldRPDepression and anxiety in visually impaired older peopleOphthalmology2007114228328817270678

- BurmediDBeckerSHeylVWahlH-WHimmelsbachIEmotional and social consequences of age-related low visionVis Impair Res20024147

- LamersFJonkersCCBosmaHDiederiksJPvan EijkJTEffectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a minimal psychological intervention to reduce non-severe depression in chronically ill elderly patients: the design of a randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN92331982]BMC Public Health2006616116790039

- IsHakWWGreenbergJMBalayanKQuality of life: the ultimate outcome measure of interventions in major depressive disorderHarv Rev Psychiatry201119522923921916825

- National Institute of Mental HealthDepressionDepartment of Health and Human Services2011 Available from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression/depression-booklet.pdfAccessed November 8, 2012

- VerbruggeLMJetteAMThe disablement processSoc Sci Med19943811148146699

- WestSSommerAPrevention of blindness and priorities for the futureBull World Health Organ2001793211217662

- TaylorHRKeeffeJEVuHTVision loss in AustraliaMed J Aust20051821156556815938683

- SandersonSTattIDHigginsJPTools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliographyInt J Epidemiol200736366667617470488

- ChoMKBeroLAInstruments for assessing the quality of drug studies published in the medical literatureJAMA199427221011048015115

- BergnerMBobbittRACarterWBGilsonBSThe Sickness Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status measureMed Care19811987878057278416

- CohenJStatistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences2nd edHillsdale, NJL Erlbaum Associates1988

- ReinhardtJPBoernerKHorowitzAPersonal and social resources and adaptation to chronic vision impairment over timeAging Ment Health200913336737519484600

- Shmuely-DulitzkiYRovnerBWZisselmanPThe impact of depression on functioning in elderly patients with low visionAm J Geriatr Psychiatry199534325329

- HorowitzAReinhardtJBoernerKTravisLThe influence of health, social support quality and rehabilitation on depression among disabled eldersAging Ment Health20037534235012959803

- HorowitzAReinhardtJPBoernerKThe effect of rehabilitation on depression among visually disabled older adultsAging Ment Health20059656357016214704

- HorowitzABrennanMReinhardtJPMacMillanTThe impact of assistive device use on disability and depression among older adults with age-related vision impairmentsJ Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci200661B5S274S28016960241

- RovnerBWCastenRJTasmanWSEffect of depression on vision function in age-related macular degenerationArch Ophthalmol200212081041104412149057

- RovnerBWCastenRJNeuroticism predicts depression and disability in age-related macular degenerationJ Am Geriatr Soc20014981097110011555073

- HaymanKJKerseNMLa GrowSJWouldesTRobertsonMCCampbellAJDepression in older people: visual impairment and subjective ratings of healthOptom Vis Sci200784111024103018043421

- BrodyBLGamstACWilliamsRADepression, visual acuity, comorbidity, and disability associated with age-related macular degenerationOphthalmology2001108101893190011581068

- FolsteinMFRomanoskiAJNestadtGBrief report on the clinical reappraisal of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule carried out at the Johns Hopkins site of the Epidemiological Catchment Area Program of the NIMHPsychol Med19851548098144080884

- WareJEJrSherbourneCDThe MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selectionMed Care19923064734831593914

- Center for the Study of Aging and Human DevelopmentThe OARS Methodology1st edDurham, NCDuke University1975

- BergnerMBobbittRAKresselSPollardWEGilsonBSMorrisJRThe Sickness Impact Profile: conceptual formulation and methodology for the development of a health status measureInt J Health Serv197663393415955750

- ReinhardtJPThe importance of friendship and family support in adaptation to chronic vision impairmentJ Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci199651B5P268P2788809003

- MassofRWAhmadianLGroverLLThe Activity Inventory: an adaptive visual function questionnaireOptom Vis Sci200784876377417700339

- HorowitzATeresiJACasselsLADevelopment of a vision screening questionnaire for older peopleJ Gerontol Soc Work1991173–43756

- MangioneCMLeePPPittsJGutierrezPBerrySHaysRDPsychometric properties of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ). NEI-VFQ Field Test InvestigatorsArch Ophthalmol199811611149615049823352

- ScottIUScheinODWestSBandeen-RocheKEngerCFolsteinMFFunctional status and quality of life measurement among ophthalmic patientsArch Ophthalmol199411233293358129657

- SteinbergEPTielschJMScheinODThe VF-14. An index of functional impairment in patients with cataractArch Ophthalmol199411256306388185520

- RovnerBWCastenRJHegelMTTasmanWSMinimal depression and vision function in age-related macular degenerationOphthalmology2006113101743174716893569

- RovnerBWCastenRJMassofRWLeibyBETasmanWSWillsEyeAMD StudyPsychological and cognitive determinants of vision function in age-related macular degenerationArch Ophthalmol2011129788589021746979

- TabrettDRLathamKFactors influencing self-reported vision-related activity limitation in the visually impairedInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20115285293530221613370

- NeugartenBLHavighurstRJTobinSSThe measurement of life satisfactionJ Gerontol19611613414313728508

- FerransCEPowersMJQuality of life index: development and psychometric propertiesANS Adv Nurs Sci19858115243933411

- AdamsDLAnalysis of a life satisfaction indexJ Gerontol19692444704745362359

- BlazerDHughesDCGeorgeLKThe epidemiology of depression in an elderly community populationGerontologist19872732812873609795

- GrunebaumMFOquendoMAManlyJJDepressive symptoms and antidepressant use in a random community sample of ethnically diverse, urban elder personsJ Affect Disord20081051–327327717532052

- ParkJHLeeJJLeeSBPrevalence of major depressive disorder and minor depressive disorder in an elderly Korean population: results from the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging (KLoSHA)J Affect Disord20101251–323424020188423

- FuttermanAThompsonLGallagher-ThompsonDFerrisRDepression in later life: epidemiology, assessment, etiology, and treatmentHandbook of Depression2nd edNew York, NYGuilford Press1995

- BruceMLSeemanTEMerrillSSBlazerDGThe impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur studies of successful agingAm J Public Health19948411179617997977920

- KatonWJClinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illnessBiol Psychiatry200354321622612893098

- YoungBAVon KorffMHeckbertSRAssociation of major depression and mortality in Stage 5 diabetic chronic kidney diseaseGen Hosp Psychiatry201032211912420302984

- CullumSMetcalfeCToddCBrayneCDoes depression predict adverse outcomes for older medical inpatients? A prospective cohort study of individuals screened for a trialAge Ageing200837669069519004962

- LengCHWangJDLong term determinants of functional decline of mobility: an 11-year follow-up of 5464 adults of late middle aged and elderlyArch Gerontol Geriatr201357221522023608344

- KaburagiTHirasawaRYoshinoHNutritional status is strongly correlated with grip strength and depression in community-living elderly JapanesePublic Health Nutr201114111893189921426623

- KiyakHATeriLBorsonSPhysical and functional health assessment in normal aging and in Alzheimer’s disease: self-reports vs family reportsGerontologist19943433243308076873

- KurianskyJBGurlandBJFleissJLThe assessment of self-care capacity in geriatric psychiatric patients by objective and subjective methodsJ Clin Psychol1976321951021249244

- KennedyGJKelmanHRThomasCThe emergence of depressive symptoms in late life: the importance of declining health and increasing disabilityJ Community Health1990152931042141337

- KoenigHGGeorgeLKDepression and physical disability outcomes in depressed medically ill hospitalized older adultsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry1998632302479659956

- PenninxBWGuralnikJMFerrucciLSimonsickEMDeegDJWallaceRBDepressive symptoms and physical decline in community-dwelling older personsJAMA199827921172017269624025

- DunlopDDManheimLMSongJLyonsJSChangRWIncidence of disability among preretirement adults: the impact of depressionAm J Public Health200595112003200816254232

- Cronin-StubbsDde LeonCFBeckettLAFieldTSGlynnRJEvansDASix-year effect of depressive symptoms on the course of physical disability in community-living older adultsArch Intern Med2000160203074308011074736

- BarryLCSoulosPRMurphyTEKaslSVGillTMAssociation between indicators of disability burden and subsequent depression among older personsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci201368328629222967459

- BlazerDGDepression in late life: review and commentaryJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200358A324926512634292

- KatonWJEpidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illnessDialogues Clin Neurosci201113172321485743

- IshakWWHaKKapitanskiNThe impact of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and their combination on quality of life in depressionHarv Rev Psychiatry201119627728922098324

- AreánPARauePMackinRSKanellopoulosDMcCullochCAlexopoulosGSProblem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunctionAm J Psychiatry2010167111391139820516155

- TousmanSZeitzHTaylorLDA pilot study assessing the impact of a learner-centered adult asthma self-management program on psychological outcomesClin Nurs Res2010191718819933878

- GirdlerSJBoldyDPDhaliwalSSCrowleyMPackerTLVision self-management for older adults: a randomised controlled trialBr J Ophthalmol201094222322820139291

- PackerTLGirdlerSBoldyDPDhaliwalSSCrowleyMVision self-management for older adults: a pilot studyDisabil Rehabil200931161353136119340618

- BrodyBLRoch-LevecqA-CGamstACMacleanKKaplanRMBrownSISelf-management of age-related macular degeneration and quality of life: a randomized controlled trialArch Ophthalmol2002120111477148312427060

- BrodyBLRoch-LevecqA-CThomasRGKaplanRMBrownSISelf-management of age-related macular degeneration at the 6-month follow-up: a randomized controlled trialArch Ophthalmol20051231465315642811

- LeeLPackerTLTangSHGirdlerSSelf-management education programs for age-related macular degeneration: a systematic reviewAustralas J Ageing200827417017619032617

- BrodyBLFieldLCRoch-LevecqA-CMoutierC YEdlandSDBrownSITreatment of depression associated with age-related macular degeneration: a double-blind, randomized, controlled studyAnn Clin Psychiatry201123427728422073385

- RovnerBWCastenRJHegelMTLeibyBETasmanWSPreventing depression in age-related macular degenerationArch Gen Psychiatry200764888689217679633

- PackerTLGirdlerSBoldyDPDhaliwalSSCrowleyMVision self-management for older adults: a pilot studyDisabil Rehabil200931161353136119340618

- FenwickEKLamoureuxELKeeffeJEMellorDReesGDetection and management of depression in patients with vision impairmentOptom Vis Sci200986894895419609229

- UnutzerJDiagnosis and treatment of older adults with depression in primary careBiol Psychiatry200252328529212182933

- BakerJKeenanLZwischenbergerJA model for primary care psychology with general thoracic surgical patientsJ Clin Psychol Med Settings2005124359366

- SaundersSMWojcikJVThe reliability and validity of a brief self-report questionnaire to screen for mental health problems: the Health Dynamics InventoryJ Clin Psychol Med Settings2004113233241

- CrystalSSambamoorthiUWalkupJTAkincigilADiagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly Medicare population: predictors, disparities, and trendsJ Am Geriatr Soc200351121718172814687349

- UnutzerJKatonWCallahanCMCollaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trialJAMA2002288222836284512472325

- BeekmanATvan der Feltz-CornelisCvan MarwijkHWEnhanced care for depressionCurr Opin Psychiatry201326171223196996

- SimonGCollaborative care for mood disordersCurr Opin Psychiatry2009221374119122533

- HaleyWEMcDanielSHBrayJHPsychological practice in primary care settings: practical tips for cliniciansProf Psychol Res Pr1998293237244

- ReesGMellorDHeenanMDepression training program for eye health and rehabilitation professionalsOptom Vis Sci201087749450020473238