Abstract

The proportion of the population over 65 years old continues to grow. Chronic rhinosinusitis is common in this population and causes a reduction in quality of life and an increase in health care utilization. Diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps follows the same principles for elderly patients as in the general population, but the elderly population presents some diagnostic challenges worth considering. Presbynasalis, the anatomic and functional changes of the nose and paranasal sinuses associated with aging must be accounted for when caring for these patients. In addition, polypharmacy and other medical issues that can cause similar symptoms must be considered. Medical therapy is generally similar to the general population but with additional concerns given the propensity for geriatric patients to be on multiple medications and to suffer from multiple medical issues. Sinus surgery should be considered following the same indications as in the general population. While some authors have found higher complication rates in endoscopic sinus surgery, others have found higher rates of success. As always, the risks of surgery must be considered with the possible benefits on a patient-to-patient basis.

Keywords:

Introduction

The proportion of the US population that is over 65 years old is growing. It is estimated that over 20% of the population will be over 65 years old by 2050.Citation1 In 2015, patients over 65 years old were responsible for 58% of all specialist visits.Citation2 More specifically, chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is the sixth most common chronic disease in the elderly.Citation3 CRS is also significantly more common in people over 65 years old.Citation4 Furthermore, rates of nasal polyps have been shown to be significantly higher in elderly patients with CRS.Citation5 On an individual level, CRS can worsen sleep quality and fatigue.Citation6 Soler et al found that patients with CRS reported more cognitive dysfunction, and objectively, they had worse response times on computerized testing.Citation7 Another group led by Soler looked at baseline health state utility values in CRS. Health state utility values range from 0 to 1, with 0 being death and 1 representing perfect health. CRS scored 0.65 - similar to coronary artery disease requiring percutaneous coronary intervention, congestive heart failure, and Parkinson’s disease.Citation8 CRS in the elderly also appears to have a significant financial impact. Recently, Bhattacharyya et al reported that the annual incremental cost for patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) compared to patients without CRS was $11,507.Citation9 Clearly, CRSwNP can cause significant reduction in quality of life and overall health as the negative impacts of CRSwNP are multiple and extend well past classic symptoms of sinus disease. The elderly population may be more susceptible to these negative effects as evidenced by the fact that healthcare utilization was found to be higher in the elderly population with CRS as well.Citation10 With CRSwNP being a more common problem in the elderly, building an understanding of diagnosis and management specifically for this patient population is important. The elderly population is growing, and they are at higher risk for suffering from CRSwNP. For these reasons, a review of the current understanding of CRSwNP in the elderly population is of value. The elderly population poses some challenges in the management of CRSwNP. These fall into three broad categories: diagnostic challenges, challenges with medical management, and challenges posed by surgical intervention. In conclusion, solutions will be discussed for each category.

Epidemiology

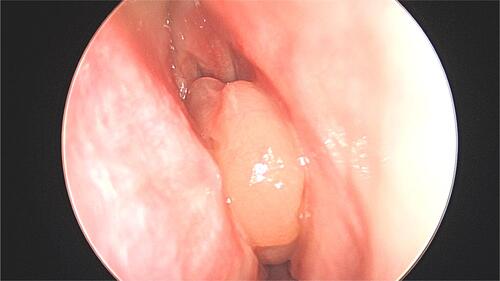

Nasal polyps have been recognized for millennia with references dating back to Egypt around 2000 B.C.Citation11 Nasal polyps are well recognized today as a relatively common nasal mass, typically developing in the setting of nasal inflammation (). Classically, chronic rhinosinusitis is separated into two main classes based on the presence of nasal polyps: CRSwNP and chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps (CRSsNP). As noted above, this review will focus on CRSwNP.

The incidence of CRSwNP is reported to be around 1–4%; however, there is a significant possibility that this is a conservative estimate given the importance of endoscopy for diagnosis.Citation12,Citation13 Supporting this, autopsy studies have found a higher prevalence, although the clinical significance of this finding remains unknown.Citation11 The incidence is higher in men and significantly increases in patients over 40 years old. Prevalence appears to peak in the 4th to 6th decades of life.Citation5,Citation13 According to the European Position paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps (EPOS 2020), ~5% of elderly adults (greater to or equal to 60 years old) suffer from CRSwNP.Citation14 Cho et al found that in patients with CRS, the elderly cohort trended towards having a higher rate of nasal polyps.Citation15 This same group later reinforced this finding and actually found a statistically significant increase in the proportion of elderly patients with polyps.Citation16

An interesting component of the work performed by Yancey et al looked at the overall health of patients with CRS. Using Short Form 8 (SF-8), they assessed the subjective health of patients with CRS and compared this to age-matched patients from the general population. They found that patients over 60 years old scored significantly worse in 7 of 8 domains, while middle-aged patients and young patients scored worse in 6 and 4 of 8, respectively.Citation2 This shows that it is possible that CRS disproportionately affects the general health of the elderly population.

Presbynasalis

To understand how CRSwNP affects the elderly population, one must first understand the expected changes that occur within the nose and sinuses that accompany aging. Presbynalis is the term used to refer to the changes in sinonasal anatomy and function that are part of normal aging.Citation17

Anatomically, multiple factors can change nasal airflow. Nasal tip support weakens, and the tip can become ptotic due to weakening of the connective tissues, as well as loss of muscle mass of the facial muscles. In addition, the septal cartilage can fragment, and the columella can retract.Citation3 Combined together, all of these factors can lead to a reduction in nasal airflow.

Interestingly, both acoustic rhinometry and computed tomography (CT) studies have found that nasal volume increases with age; however, intranasal resistance has also been shown to increase with age.Citation18–Citation20 This seemingly contradictory set of findings has been explained by the loss in elasticity of the nasal tissues. Another finding of unclear significance is the fact that the nasal cycle seems to significantly diminish in patients over 50 years old.Citation21 The cause of this is not apparent, but it could contribute to feelings of congestion in the elderly population.

On a microscopic level, cilia beat frequency decreases, therefore impairing mucociliary clearance.Citation22,Citation23 The percentage of body weight that is water decreases with age as well resulting in thicker mucus.Citation17 Nasal blood flow is reduced, impairing the ability of the nares to humidify and warm the air, contributing to nasal dryness.Citation24 These factors result in thicker mucus that is more resistant to clearance. In addition, sympathetic tone decreases compared to parasympathetic activity further resulting in an exacerbation of mucosal excretory activity.Citation17

From a functional standpoint, there are some key changes that occur with age. First, olfaction frequently falters in the elderly, with up to half of patients aged 65–80 years showing some deficit.Citation17 This is amplified over 80 years old, with over 75% of patients experiencing olfactory dysfunction.Citation25 Etiology is multifactorial and can obscure underlying diagnoses. The neuroepithelium of the olfactory groove thins, while the density of receptors also decreases.Citation26 Of note, this is magnified in smokers. This change in sense of smell results in impaired sense of flavor and impacts quality of life in many patients. As loss in sense of smell is a key symptom of CRSwNP, the olfactory changes accompanying aging can cloud the diagnosis. Following in this vein, the elderly population can experience olfactory dysfunction as a normal variant of aging, as a symptom of CRS, or as a presenting symptom of other illnesses, such as neurodegenerative disorders further obscuring the picture.

The importance of a functioning sense of smell is sometimes lost on patients. Santos et al reported that 37% of patients with olfactory dysfunction have had a hazardous event precipitate from their sensory loss.Citation27 Due to the risks posed, olfactory changes should be taken seriously, and patients should be assessed for possible treatable causes. Proper counseling on the risks posed by hyposmia/anosmia is important as well.

Immunosenescence, the waning of the immune system in old age, also results in an increased susceptibility to pathogens. Serum IgE levels drop, and eosinophils have a weaker response to cytokines.Citation16 As patients age, changes in antigen presentation also lead to a generally weaker immune response. In addition to this age-related diminished response and function, elderly patients also develop a baseline chronic inflammation with higher circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines.Citation28,Citation29

As humans age, some sinonasal changes are expected. These can be anatomic, microscopic, functional or immunologic (). It is important to keep these changes in mind when evaluating a patient with concerns for CRS.

Table 1 Common Findings in Presbynasalis.Citation17

Pathophysiology

As explained above, CRS is split into two phenotypes - CRSwNP and CRSsNP. It is still not clear why some patients with CRS develop polyps, while others do not. Polyps are driven by inflammatory reactions driving edema, hypertrophy and outgrowth of nasal mucosa.Citation30 Polyps are benign but cause significant functional problems including nasal obstruction and anosmia. CRSwNP is uncommon in children and often presents later in life.Citation5 Adult-onset asthma is frequently seen in patients with CRSwNP.Citation5,Citation12

Both host and environmental factors play a role in the development of CRSwNP. Some host factors include impaired mucociliary clearance, dysregulation of epithelial barrier functions in the sinonasal mucosa, innate immunity and an imbalance in the microbiome of the sinonasal tract.Citation12,Citation31 These host factors leave the individual more subject to environmental factors, such as allergens and bacteria. In older adults, S100 protein levels are significantly lower.Citation15 S100 family proteins play a key role in the function of the epithelial barrier as well as the repair of the epithelial barrier.Citation28 Interestingly, Jiang et al found that elderly patients with CRSwNP were more likely to display more severe tissue edema in terms of tissue remodeling on a histological level.Citation32 The microbiome changes as patients age with a greater burden of Fusobacteria and S. aureus compared to younger patients.Citation33,Citation34 Barrier function impairment has also been linked to Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.Citation35

Impaired mucociliary clearance combined with thicker mucus seen in the elderly population results in prolonged contact of the epithelium with irritants. Excess secretions can drive local tissue hypoxia, further impairing mucociliary clearance and worsening the problem.Citation31 Though initially believed to be predominantly driven by a type 2 immune response, CRSwNP has been shown to present with type 1, type 2, and type 3 responses.Citation31

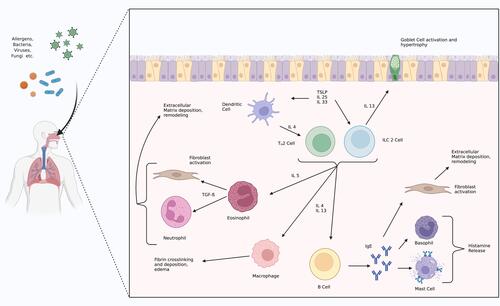

Type 2 responses involve upregulation of interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-5, IL-13, and IgE.Citation12,Citation36 Eosinophilia is also characteristic.Citation37 In a type 2 response, various insults can stimulate a cytokine cascade that leads to stimulation of ILC-2 cells and TH2 cells to release IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. IL-5 drives eosinophilia, while IL-4 and IL-13 activate macrophages, stimulate goblet cells, and promote class switching in B cells to promote production of IgE.Citation38 Through these pathways, edema develops, and mast cells and basophils release histamine and extracellular matrix deposition in driven by macrophages and fibroblasts.Citation38,Citation39 The combination of extracellular matrix deposition and inflammatory edema drives the remodeling process underlying polyp formation. This process is demonstrated in . Non-type 2 responses include type 1 and type 3 responses. Type 1 responses are mediated by interferon gamma, tumor necrosis factor and lymphotoxin alpha leading to macrophage activation and an upregulation of IgG.Citation36 Type 1 responses also show a high level of neutrophilic activation. Type 3 responses are mediated by IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-22.Citation36 Type 3 responses trigger neutrophil proliferation and recruitment.Citation36

Figure 2 Type 2 inflammation pathways.

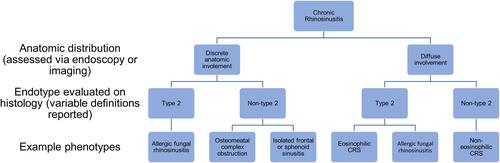

CRSwNP as a broad phenotype has been further broken down into a wide array of endotypes based on the infiltrate immune cells, cytokines present, and inflammatory mediators present.Citation37 Eosinophilic infiltrates driven by type 2 response are a key component of most descriptions.Citation14,Citation40,Citation41 There are two endotypes frequently mentioned in the literature – eosinophilic (also referred to as type 2 mediated) nasal polyps (E-NP) and non-eosinophilic (also termed neutrophilic or non-type 2 mediated) nasal polyps (NE-NP). A breakdown described by Grayson et al is included below in .Citation36 While this is useful, it is important to note that these classes are not binary and likely represent points on the spectrum.Citation37 Specifically, in the elderly population, there is evidence that they may be more likely to have a response that is less dominated by type 2 responses.Citation28 Multiple studies have offered a more granular breakdown of endotypes, but that is beyond the scope of this review as it appears that the eosinophilic component is the most clinically relevant. Due to the variability of the studies reporting on this issue, there is no clear cutoff of what defines eosinophilic CRSwNP.Citation42

In terms of differentiating endotypes, histology is the gold standard. However, multiple methods of testing have been described in an effort to identify patients with eosinophilic CRSwNP without direct histology.Citation41,Citation43,Citation44 Both absolute eosinophil count and blood eosinophil percentage have been found to be reasonably good at differentiating patients CRSwNP into E-NP and NE-NP.Citation41,Citation43 However, some researchers have concerns as these measures do not actually investigate whether eosinophilic cytokines are present.Citation31 Elevated IgE levels have also been correlated with E-NP.Citation43

Presentation and Diagnosis

Chronic rhinosinusitis is defined as 12 weeks of at least two of the following symptoms: nasal congestion or obstruction, rhinorrhea, posterior nasal drainage, facial pain or pressure, change in sense of smell, and either endoscopic signs of disease or CT findings consistent with inflammatory disease.Citation45 For CRS to be diagnosed, one of the symptoms reported must be either nasal obstruction/congestion or nasal discharge (anterior or posterior).Citation14 CRS should not be diagnosed solely on radiographic studies given the high incidence of radiological anomalies.Citation46

Elderly patients reported loss of sense of smell more frequently, and rhinorrhea and nasal obstruction less frequently.Citation30 In one prospective case series, elderly patients with CRS were also found to be more likely to present with polyps.Citation47 This study reported that facial pain, environmental allergy and rhinorrhea were more common in the younger groups.

CRSwNP has significant overlap with CRSsNP in terms of symptoms, so a physical exam is critical. In most cases, polyps are present bilaterally. While large polyps can be seen on anterior rhinoscopy, nasal endoscopy is often needed in identifying polypoid disease, as clinically significant polypoid disease may be missed on anterior rhinoscopy.Citation11 While the classic presentation of nasal polyps on exam is pale grayish smooth masses in the nasal cavity, often emanating from the ethmoid sinuses, they can still be heterogeneous ().Citation12 Polyps may appear yellowish, translucent or even erythematous. Clinical diagnosis can be made based on history and clinical examination. If there is any doubt as to the character of a nasal mass, imaging should be pursued prior to biopsy.

In addition to presbynasalis, there are other clinical entities that can complicate diagnosis. Importantly, polypharmacy must be considered as many common pharmaceutical compounds list “rhinitis” as a possible side effect. This is particularly germane to the elderly population, as patients over 65 years old use at least 5 medications on average.Citation3

For patients with suspected polyps, imaging plays an important role in diagnosis and management. For sinonasal pathology, a non-contrasted CT scan is the preferred imaging modality. Imaging plays a key role in the identification of characteristics that could make early surgical intervention more favorable, such as mucocele formation, intraorbital extension, and intracranial extension of disease.Citation11 Magnetic resonance imaging is often unnecessary in CRSwNP, unless there is concern for spread beyond the paranasal sinuses.

CRSwNP has a highly variable disease course, and there is no reliable way to predict what an individual patient may go on to experience. Some will experience mild symptoms that cause little effect on quality of life. Others may have recurrent exacerbations of obstructive bacterial sinusitis requiring antibiotics; however, many may have obstruction of sinuses without ever-experiencing bacterial sinusitis.Citation11 Unfortunately, some will have persistent diseases requiring multiple surgical interventions. There are many grading systems and scoring systems that attempt to stratify the severity of the disease. A few of the most commonly used ones are outlined in .

Table 2 Common Scoring Systems Used to Assess CRS Severity.Citation14

Important to consider in a patient with CRSwNP is concomitant asthma. There is a strong association between CRS and asthma even in the elderly population.Citation48 Even if patients had not previously been diagnosed with asthma, it is important to consider this and screen patients with CRS so that they may be directed to proper providers for asthma workup if indicated.

Along a similar vein, when patients present with nasal polyps, aspirin exacerbated respiratory disorder (AERD) should be considered. The triad of aspirin sensitivity, asthma, and nasal polyps often develops insidiously, and diagnosis is often made years after the onset of symptoms.Citation49 When on a consistent daily low-dose aspirin (81 mg), adverse reactions may not occur until the patient is off aspirin for a few days and then restarts further obscuring the diagnosis of AERD.Citation50,Citation51 Given that elderly patients are more likely to be prescribed aspirin, a consideration of a patient’s medical history and medication list may offer insight into the etiology of sinus disease. A related disease, NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disorder (N-ERD), has been shown to be associated with older age.Citation52 As elderly patients may receive NSAID prescriptions for arthritis and other age-related diseases, this is important to keep in mind as well.

Medical Therapy

Intranasal Therapies

Baseline medical therapy for patients with CRS, regardless of the presence of polyps, consists of intranasal corticosteroids and nasal saline irrigations. Benefits include improved mucociliary clearance, disruption of biofilms, clearance of allergens, and improvement in mucus clearance.Citation45 Nasal irrigations have been shown to be beneficial in a Cochrane review, but proper technique is important to review with patients.Citation53

Intranasal steroids reduce airway inflammation.Citation45 Side effects are generally mild and include epistaxis, nasal itching and headache. Epistaxis is important to counsel patients on as presbynasalis leads to thinning of the nasal mucosa, theoretically increasing the risk for epistaxis. Also, elderly patients tend to have a higher propensity to be on anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications, possibly further increasing the risk of epistaxis. Long-term use has been shown to be safe, and no impact on systemic cortisol levels has been found.Citation14 Importantly, despite the fact that the elderly population is more likely to suffer from cataracts and glaucoma, long-term use of intranasal steroids has not been shown to increase lens opacity or intraocular pressure.Citation54

A key component of intranasal corticosteroid use is proper technique – aiming away from the septum by using the contralateral hand for an individual nare.Citation45 An assessment of the patient’s ability to effectively use intranasal steroids is important. There may be some concern about the dexterity required to self-administer these medications in the elderly due to issues such as arthritis. However, a survey study showed that over 95% of elderly patients and patients with arthritis found mometasone furoate nasal spray easy to use.Citation55 If individual patients struggle with certain administration devices, others can be used. Providers can consider adding steroids to nasal irrigations if patients find irrigation bottles easier to use.Citation14 This could also be of value in patients using an auto-irrigator device. If these methods are unsuccessful, nasal steroid drops can be considered. If achieving proper posture during administration is not possible, an exhalation delivery system may improve usability. Regardless of which method is chosen, the provider must adequately educate the patient on proper technique.

Oral Steroids

Short courses of oral corticosteroids are a valuable component of the medical management of CRSwNP, improving both subjective and objective measures.Citation14,Citation56 However, the side effect profile must be considered. This is especially true in the elderly population. Problems common in the geriatric population such as osteoporosis, diabetes and hypertension can all be exacerbated acutely by oral corticosteroids.Citation3 Even short courses of steroids can have negative cognitive and psychiatric effects, including memory issues.Citation57 With underlying memory issues more common in the elderly, this possible worsening must be seriously considered. Steroids can also negatively impact bone health. Within one month of use, apoptosis of osteoblasts can be seen. Steroids exert an anti-vitamin D effect, reducing calcium absorption and increasing bone absorption.Citation57 Short courses of under 12 days have been shown to result in a reduction in bone formation in the elderly.Citation58 This is important to consider in the elderly population as they are more likely to have lower bone density and vitamin D deficiency at baseline. Judicious use of oral corticosteroids is important and must be made on an individualized basis. If the risks are not disproportionate, a short course of oral corticosteroids is worth consideration for CRSwNP.Citation46 Long-term use of steroids increases the risks of problems such as osteoporosis, glaucoma, cataract, adrenal failure, peptic ulcer, gastritis, diabetes mellitus and hypertension.Citation57 Therefore, long-term use should be discouraged. It is important to keep systemic effects of corticosteroids in mind even when prescribing low doses and short courses.

Oral Antibiotics

Generally, in CRSwNP a trial of a three-week course of doxycycline is worth consideration for symptomatic management.Citation46,Citation59 Short-term antibiotic regimens are frequently used in CRS to treat acute exacerbations; however, if treatment directed at the inflammatory basis of CRS is not initiated, antibiotic regimens will only provide temporary benefit.Citation45 When possible, culture directed antibiotics are preferable. According to the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG), acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in elderly patients should be treated with amoxicillin with clavulanate for 10 days if not allergic. In patients with penicillin allergy, doxycycline or a respiratory fluoroquinolone is recommended. Some have argued for extended courses of macrolide therapy as an anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory agent, but studies on the efficacy of macrolide therapy have been mixed and no recommendation for use could be made by EPOS 2020.Citation14 With further understanding of endotypes, more targeted macrolide therapy may prove of value in the future. One key point to consider when contemplating macrolide therapy in the elderly population is the growing evidence that macrolides carry a notable cardiovascular risk.Citation60–Citation62 As the elderly population is more likely to have underlying cardiovascular conditions, this is especially important. Importantly, clarithromycin specifically should not be used in patients who are on statins due to CYP3A4 inhibition.Citation14

Biologics

According to EPOS 2020, patients qualify for consideration for biologics if they have bilateral nasal polyposis, have failed endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) and meet three of the following criteria:Citation14

Evidence of type 2 inflammation shown by tissue eosinophils greater than or equal to 10 per high-powered field, blood eosinophilia with greater than or equal to 250, or total IgE greater than or equal to 100.

Repeated need for systemic corticosteroids (two or more courses per year or long-term need (over 3 months)).

Sinonasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22) greater than or equal to 40.

Anosmia on standardized smell test.

Asthma requiring inhaled corticosteroids.

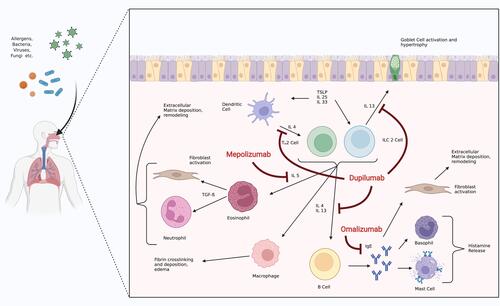

Patients should be evaluated for response in those five areas at 16 weeks and at 1 year. If no response is found, biologics should be discontinued. The same indications apply to elderly patients. Dupilumab, mepolizumab and omalizumab are currently the FDA approved for treatment of CRSwNP.

Dupilumab is an antagonist of the alpha subunit of the IL-4 receptor. Through this inhibition, the IL-4 and IL-13 pathways are blocked. The LIBERTY NP SINUS 24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS 52 trials both showed promise in dupilumab as a viable treatment option for CRSwNP. Collectively, the studies showed an improvement in nasal polyp score, Lund Mackay score, UPSIT, and SNOT-22 scores at 24 weeks and an improvement in SNOT-22 and nasal polyp scores at 52 weeks.Citation63 Mepolizumab inhibits eosinophilia via blockade of IL-5. The SYNAPSE trial showed that Mepolizumab was associated with an improvement in SNOT-22 scores as well as nasal polyp scores after 52 weeks of treatment.Citation64 Omalizumab is an anti-IgE antibody. The POLYP 1 and POLYP 2 trials showed an improvement in SNOT-22, UPSIT, and nasal polyp scores at 24 weeks.Citation65 shows where each of these medications impacts the inflammatory reaction underlying CRSwNP. As more biologics become available, a more personalized approach to each patient’s disease endotype may be possible.

Figure 4 Inflammatory pathways underlying CRSwNP with current biologic agents approved for CRSwNP and their mechanism of action.

Surgery for CRSwNP in the Elderly Patient

ESS is indicated in patients with CRSwNP who have failed appropriate medical therapy (nasal saline irrigation, intranasal corticosteroids, with or without oral corticosteroids). As CRSwNP is not a life-threatening condition, care must be taken to assess the patient’s comorbidities and anesthetic risk. When medical management fails, surgery is the next consideration. Indications for surgery in the elderly population are the same as in the general population.Citation3

Studies looking at ESS in CRS overall show generally positive results, with a few studies showing areas of concern. Colclasure et al showed in 2004 that ESS is safe and efficacious in the elderly population with a significant improvement in Sinonasal Outcome Test-20 (SNOT-20) scores.Citation66 Ramadan et al found that elderly patients undergoing primary ESS had similar complication rates to the general population; however, they found that elderly patients undergoing revision ESS had significantly higher rates of complications.Citation67 Jiang and Hsu reported that ESS resulted in a subjective improvement in sinus symptoms in patients over 65 years old at a higher rate than younger patients but also noted higher complication rates.Citation68 Krings et al also found higher complication rates in the elderly population.Citation69 Gardner et al recently contradicted that by showing no difference in complication rates or intraoperative blood loss.Citation70

Importantly, in 2007, one study showed that the quality-of-life improvements seen in ESS in the general population were still present in the elderly population.Citation71 In 2018, Lehmann et al bolstered this argument by showing that SNOT-22 scores improved with ESS.Citation72 In 2021, Helman et al found ” … geriatric patients have reduced operative time and blood loss, have significant reductions in post-operative SNOT-22 and NOSE scores, and have fewer minor complications than the younger cohort”.Citation73 All of this was despite the fact that the elderly cohort had a higher rate of comorbidities. Gardner et al found significant improvement in SNOT-22 scores in elderly patients undergoing ESS as well.Citation70 At this time, the rate of complications in ESS for CRS in elderly patients in comparison with younger patients has not been definitively established, but the effectiveness of surgery appears well established.

Although the data are sparser when looking at CRSwNP specifically, the data are more favorable. Lee and Lee found that geriatric patients undergoing ESS for CRSwNP had the best outcomes compared to other age groups as determined by endoscopic exam at least 6 months after surgery.Citation74 In a small study looking at 20 patients, Shin et al assessed Lund Mackay scores pre and postoperatively and made comparisons between a cohort of elderly patients and a cohort of young adults. The elderly cohort showed further improvement in Lund Mackay scores postoperatively, although this did not meet significance.Citation75 Again, looking specifically at CRSwNP, Brescia et al compared outcomes in patients aged 65 years and older to a young adult (20–40 years old) cohort. Forty-three elderly patients and 71 young adult patients all with CRSwNP who underwent ESS were included. They found that the rate of recurrence was lower in the elderly population compared to the young adult population (11.6% vs 28.2%).Citation76 A prospective study done by the same group found no significant relationship between age and recurrence.Citation77 Looking more specifically at a subset of patients who have non-eosinophilic nasal polyps, post-operative Lund Kennedy scores were again significantly decreased specifically in the elderly population compared to the young population.Citation78 ESS for CRSwNP seems favorable in this age group if indicated. Interestingly, some have suggested that more limited surgery could be considered in the elderly population if significant comorbidities exist. Ideally, this would significantly shorten operative time while still providing benefits given the favorable response the elderly population with CRSwNP seems to have to surgery.Citation78

As research on endotypes continues to offer more insight on CRSwNP, certain patterns have started to develop in terms of treatment response. Wen et al showed that patients with non-eosinophilic CRSwNP have a significantly less robust response to systemic glucocorticoids.Citation79 Interestingly, polyps with a high eosinophilic component appear to have higher rates of recurrence, but this does not seem to be true in the elderly population.Citation80–Citation82 This idea was echoed by Cho et al who found that in elderly patients, on average, although eosinophil infiltration was unchanged, eosinophil cationic protein levels were significantly lower implying lower function of eosinophils.Citation15 These age-related immune system changes could contribute to differing rates of recurrence amongst patients of what seems to be the same endotype. As the understanding of endotypes improves, further delineation of expected benefits from different treatments should continue to develop.

On a more practical note, certain intraoperative interventions can help to make surgery safer and easier. Total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) has been found to be safe in the elderly population and has been shown to reduce intraoperative bleeding in rhinologic surgery.Citation83,Citation84 Topical vasoconstrictors play a key role in obtaining hemostasis during rhinologic procedures. While epinephrine is generally safe when applied topically, discussion with the anesthesia team, especially in patients with cardiac risk factors more prevalent in the elderly population, is prudent.Citation85

Alternatively, to avoid the risk of general anesthesia, consideration of the use of monitored anesthetic care or even local anesthesia for in-office procedures is reasonable.Citation85 According to Chaaban et al, patients over 60 are much more likely to undergo in-office balloon sinuplasty than younger patients.Citation86 While balloon sinuplasty is not indicated in patients with nasal polyps, some are pursuing in-office polypectomy for CRSwNP.Citation87 Patients undergoing in-office procedures can be medicated with oral pain medication and anxiolytics prior to the procedure; however, these medications should only be given after reviewing medications taken by the patient. Generous use of both topical and injected local anesthetics can make many procedures tolerable in the clinic setting. Preprocedural preparation would be very similar for these patients.

It is worth noting that a study by Rudmik et al suggests that ESS for CRS is more cost-effective than continued medical management. Their model showed ESS resulted in an overall incremental cost-effectiveness ratio under the standard accepted ratio of $50,000 per quality adjusted life year, making ESS favorable.Citation88 Importantly to this discussion, ESS has a high upfront cost, and this may disproportionately affect the elderly population. The cost-effectiveness threshold was crossed in year three after ESS.Citation88

Challenges and Solutions

Diagnostic challenges

Diagnosis can be confounded in elderly adults (presbynasalis, neurodegenerative disease, polypharmacy, etc.). It is important to keep changes in the aging nose in mind and be aware of the change in presentation of CRSwNP in the elderly population. The elderly population is more likely to present with smell changes as opposed to rhinorrhea or facial pain. Staying vigilant for neurodegenerative diseases or symptoms driven by polypharmacy is also crucial in the elderly population. A thorough review of systems, medication list and physical exam can often provide insight into possible confounders.

2. Medical management challenges

(a) Treatment regimens can pose higher risks in elderly adults

Intranasal corticosteroids are generally safe and well tolerated in the elderly population. Oral corticosteroids can offer significant symptomatic benefits in CRSwNP, but their use is limited by an unfavorable side effect profile that the elderly are particularly susceptible to. Considering the comorbidities of patients is important in determining appropriateness and counseling patients on the risks associated with steroid use. Long-term steroid use greatly increases the risk of side effects and should be avoided.

(b) The role of biologics is still developing

Elderly patients should be referred to a provider with experience using biologic agents for CRSwNP when indicated just as in the general population. Extra consideration may be given to patients who are at high surgical risk in an effort to mitigate risk.

(c) Administration of intranasal steroids may be challenging for elderly patients

If standard intranasal corticosteroid applicators are not easily used by patients due to dexterity issues or issues maintaining proper posture for administration, multiple alternatives can be considered. These include exhalation delivery systems, adding corticosteroids to nasal saline irrigations or using nasal steroid drops. Regardless of which solution is found, instruction of proper technique is imperative.

3. Surgical management challenges

(a) Elderly patients tend to have higher surgical risk

Indications for surgery in the elderly population are no different than the general population, and good results have been demonstrated repeatedly. Elderly patients tend to have more medical comorbidities, making them at higher risk for surgery. Critical evaluation of fitness for surgery is important, and appropriate referrals for presurgical evaluation are crucial to accurately counseling patients. In-office procedures should be considered when appropriate.

(b) Some have shown complication rates are higher in the elderly patients

While some authors have reported higher complication rates in the elderly population, others have contradicted this. ESS provides significant benefit to the elderly population when indicated, and some studies have shown that ESS is more effective in the elderly population. At this time, patients should be counseled on procedure-specific risks similarly to the general population.

Future Directions

Future research on CRSwNP in the elderly will continue to develop our understanding of the underlying immunologic and pathophysiologic basis of CRSwNP. Understanding the remodeling process that occurs due to inflammation leading to nasal polyposis is an area of investigation as well. On the basis of this, there is a need for an experimental model of CRS.Citation14 The role of the microbiome in CRS is also an important topic that is currently being researched. As the knowledge of endotypes progresses, investigation into how this impacts the elderly population will ideally allow for better delineation of which patient groups would benefit from certain therapies. In terms of treatment, complication rates in ESS have not been conclusively shown to be higher in the elderly population. Future research will continue to investigate this question. Investigation into the extent of surgery performed will also be of value in optimizing surgical results.Citation14 Biologic therapies are relatively new and long-term studies will allow for an understanding of long-term results and consequences. This work will also help inform future perspectives on which patients will benefit from which biologic therapy. In addition, newer biologic therapies such as benralizumab are continuing to be investigated.

Stem cell therapy is also being investigated as a possible treatment option targeting reversal of underlying tissue damage and remodeling processes driven by long-standing inflammation.Citation89 Mesenchymal stem cells have shown possible benefits such as driving down type 2 inflammatory responses and stimulating regulatory stem cells.Citation90–Citation92 Importantly, in terms of future perspectives of treatment, mesenchymal stem cells have recently been used in an animal model of CRS with encouraging results.Citation93 As our understanding of stem cells deepens, new therapeutic applications will be explored. At this time, much work remains to be done to elucidate how the promising potential of stem cells may be unlocked for clinical applications in CRSwNP.

Conclusions

CRSwNP has a significant impact on the elderly population. This will become more apparent as the proportion of the population over 65 continues to grow. The patient population presents unique challenges that must be considered when devising treatment plans.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted, gave final approval for the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States; 2014. Available from: http://usd-apps.usd.edu/coglab/schieber/psyc423/pdf/AgingNation.pdf. Accessed January 17, 2022.

- Yancey KL, Lowery AS, Chandra RK, Chowdhury NI, Turner JH. Advanced age adversely affects chronic rhinosinusitis surgical outcomes. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019;9(10):1125–1134. doi:10.1002/alr.22404

- Valdés CJ, Tewfik MA. Rhinosinusitis and allergies in elderly patients. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(2):217–231. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2018.01.009

- Hwang CS, Lee HS, Kim SN, Kim JH, Park DJ, Kim KS. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic rhinosinusitis in the elderly population of Korea. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2019;33(3):240–246. doi:10.1177/1945892418813822

- Won HK, Kim YC, Kang MG, et al. Age-related prevalence of chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps and their relationships with asthma onset. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(4):389–394. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2018.02.005

- Alt JA, Smith TL. Chronic rhinosinusitis and sleep: a contemporary review. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(11):941–949. doi:10.1002/alr.21217

- Soler ZM, Eckert MA, Storck K, Schlosser RJ. Cognitive function in chronic rhinosinusitis: a controlled clinical study. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(11):1010–1017. doi:10.1002/alr.21581

- Soler ZM, Wittenberg E, Schlosser RJ, Mace JC, Smith TL. Health state utility values in patients undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(12):2672–2678. doi:10.1002/lary.21847

- Bhattacharyya N, Villeneuve S, VN J, et al. Cost burden and resource utilization in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(9):1969–1975. doi:10.1002/lary.27852

- Jang DW, Lee HJ, Huang RJ, Cheng J, Abi Hachem R, Scales CD. Healthcare resource utilization for chronic rhinosinusitis in older adults. Healthcare. 2021;9:7. doi:10.3390/healthcare9070796

- Johnson J. Bailey’s Head and Neck Surgery: Otolaryngology. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2013.

- Wesley Burks A, Holgate ST, O’Hehir RE, et al. Middleton’s Allergy: Principles and Practice. Elsevier; 2019.

- Johansson L, Akerlund A, Holmberg K, Melén I, Bende M. Prevalence of nasal polyps in adults: the Skövde population-based study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112(7):625–629. doi:10.1177/000348940311200709

- Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C, et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology. 2020;58(Suppl S29):1–464. doi:10.4193/Rhin20.401

- Cho SH, Hong SJ, Han B, et al. Age-related differences in the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(3):858–860.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.002

- Cho SH, Kim DW, Lee SH, et al. Age-related increased prevalence of asthma and nasal polyps in chronic rhinosinusitis and its association with altered IL-6 trans-signaling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;53(5):601–606. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2015-0207RC

- DelGaudio JM, Panella NJ. Presbynasalis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6(10):1083–1087. doi:10.1002/alr.21787

- Loftus PA, Wise SK, Nieto D, Panella N, Aiken A, DelGaudio JM. Intranasal volume increases with age: computed tomography volumetric analysis in adults. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(10):2212–2215. doi:10.1002/lary.26064

- Kalmovich LM, Elad D, Zaretsky U, et al. Endonasal geometry changes in elderly people: acoustic rhinometry measurements. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(3):396–398. doi:10.1093/gerona/60.3.396

- Edelstein DR. Aging of the normal nose in adults. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(9 Pt 2):1–25. doi:10.1097/00005537-199609001-00001

- Mirza N, Kroger H, Doty RL. Influence of age on the “nasal cycle.”. Laryngoscope. 1997;107(1):62–66. doi:10.1097/00005537-199701000-00014

- Ho JC, Chan KN, Hu WH, et al. The effect of aging on nasal mucociliary clearance, beat frequency, and ultrastructure of respiratory cilia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(4):983–988. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.163.4.9909121

- Proença de Oliveira-maul J, Barbosa de Carvalho H, Goto DM, et al. Aging, diabetes, and hypertension are associated with decreased nasal mucociliary clearance. Chest. 2013;143(4):1091–1097. doi:10.1378/chest.12-1183

- Bende M. Blood flow with 133Xe in human nasal mucosa in relation to age, sex and body position. Acta Otolaryngol. 1983;96(1–2):175–179. doi:10.3109/00016488309132889

- Doty RL, Shaman P, Applebaum SL, Giberson R, Siksorski L, Rosenberg L. Smell identification ability: changes with age. Science. 1984;226(4681):1441–1443. doi:10.1126/science.6505700

- Paik SI, Lehman MN, Seiden AM, Duncan HJ, Smith DV. Human olfactory biopsy. The influence of age and receptor distribution. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118(7):731–738. doi:10.1001/archotol.1992.01880070061012

- Santos DV, Reiter ER, DiNardo LJ, Costanzo RM. Hazardous events associated with impaired olfactory function. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(3):317–319. doi:10.1001/archotol.130.3.317

- Renteria AE, Mfuna Endam L, Desrosiers M. Do aging factors influence the clinical presentation and management of chronic rhinosinusitis? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(4):598–605. doi:10.1177/0194599817691258

- Salvioli S, Monti D, Lanzarini C, et al. Immune system, cell senescence, aging and longevity–inflamm-aging reappraised. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(9):1675–1679.

- Song WJ, Lee JH, Won HK, Bachert C. Chronic rhinosinusitis with Nasal polyps in older adults: clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and comorbidity. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19(10):46. doi:10.1007/s11882-019-0880-4

- Bauer AM, Turner JH. Personalized medicine in chronic rhinosinusitis: phenotypes, endotypes, and biomarkers. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2020;40(2):281–293. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2019.12.007

- Jiang WX, Cao PP, Li ZY, et al. A retrospective study of changes of histopathology of nasal polyps in adult Chinese in central China. Rhinology. 2019;57(4):261–267. doi:10.4193/Rhin18.070

- Ramakrishnan VR, Feazel LM, Gitomer SA, Ir D, Robertson CE, Frank DN. The microbiome of the middle meatus in healthy adults. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e85507. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085507

- Leszczyńska J, Stryjewska-Makuch G, Ścierski W, Lisowska G. Bacterial flora of the nose and paranasal sinuses among patients over 65 years old with chronic rhinosinusitis who underwent endoscopic Sinus Surgery. Clin Interv Aging. 2020;15:207–215. doi:10.2147/CIA.S215917

- Nomura K, Obata K, Keira T, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase causes transient disruption of tight junctions and downregulation of PAR-2 in human nasal epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2014;15:21. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-15-21

- Grayson JW, Hopkins C, Mori E, Senior B, Harvey RJ. Contemporary classification of chronic rhinosinusitis beyond polyps vs no polyps: a review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(9):831–838. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1453

- Tomassen P, Vandeplas G, Van Zele T, et al. Inflammatory endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis based on cluster analysis of biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(5):1449–1456.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1324

- Kato A. Immunopathology of chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergol Int. 2015;64(2):121–130. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2014.12.006

- Amirapu S, Biswas K, Radcliff FJ, Wagner Mackenzie B, Ball S, Douglas RG. Sinonasal tissue remodelling during chronic rhinosinusitis. Int J Otolaryngol. 2021;2021:7428955. doi:10.1155/2021/7428955

- Maniu AA, Perde-Schrepler MI, Tatomir CB, et al. Latest advances in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps endotyping and biomarkers, and their significance for daily practice. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2020;61(2):309–320. doi:10.47162/RJME.61.2.01

- Ikeda K, Shiozawa A, Ono N, et al. Subclassification of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyp based on eosinophil and neutrophil. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(11):E1–E9. doi:10.1002/lary.24154

- Lou H, Zhang N, Bachert C, Zhang L. Highlights of eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in definition, prognosis, and advancement. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018;8(11):1218–1225. doi:10.1002/alr.22214

- Hu Y, Cao PP, Liang GT, Cui YH, Liu Z. Diagnostic significance of blood eosinophil count in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in Chinese adults. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(3):498–503. doi:10.1002/lary.22507

- Workman AD, Kohanski MA, Cohen NA. Biomarkers in chronic rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2018;38(4):679–692. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2018.06.006

- Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, et al. Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(2 Suppl):S1–S39. doi:10.1177/0194599815572097

- Bachert C, Pawankar R, Zhang L, et al. ICON: chronic rhinosinusitis. World Allergy Organ J. 2014;7(1):25. doi:10.1186/1939-4551-7-25

- Busaba NY. The impact of a patient’s age on the clinical presentation of inflammatory paranasal sinus disease. Am J Otolaryngol. 2013;34(5):449–453. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2013.03.013

- Jarvis D, Newson R, Lotvall J, et al. Asthma in adults and its association with chronic rhinosinusitis: the GA2LEN survey in Europe. Allergy. 2012;67(1):91–98. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02709.x

- Buchheit K, Bensko JC, Lewis E, Gakpo D, Laidlaw TM. The importance of timely diagnosis of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease for patient health and safety. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;6(4):203–206. doi:10.1016/j.wjorl.2020.07.003

- Lee-Sarwar K, Johns C, Laidlaw TM, Cahill KN. Tolerance of daily low-dose aspirin does not preclude aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(3):449–451. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2015.01.007

- White AA, Stevenson DD. Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(11):1060–1070. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1712125

- Andersén H, Ilmarinen P, Honkamäki J, et al. NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease: a population study. ERJ Open Res. 2022;8:1. doi:10.1183/23120541.00462-2021

- Harvey R, Hannan SA, Badia L, Scadding G, Nasal saline irrigations for the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD006394. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006394.pub2

- LaForce C, Journeay GE, Miller SD, et al. Ocular safety of fluticasone furoate nasal spray in patients with perennial allergic rhinitis: a 2-year study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(1):45–50. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.04.013

- Fromer LM, Ortiz GR, Dowdee AM. Assessment of patient attitudes about mometasone Furoate Nasal Spray: the Ease-of-Use Patient Survey. World Allergy Organ J. 2008;1(9):156–159. doi:10.1097/WOX.0b013e3181865f99

- Mullol J, Obando A, Pujols L, Alobid I. Corticosteroid treatment in chronic rhinosinusitis: the possibilities and the limits. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29(4):657–668. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2009.07.001

- Poetker DM, Reh DD. A comprehensive review of the adverse effects of systemic corticosteroids. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2010;43(4):753–768. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2010.04.003

- Paglia F, Dionisi S, De Geronimo S, et al. Biomarkers of bone turnover after a short period of steroid therapy in elderly men. Clin Chem. 2001;47(7):1314–1316. doi:10.1093/clinchem/47.7.1314

- Van Zele T, Gevaert P, Holtappels G, et al. Oral steroids and doxycycline: two different approaches to treat nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(5):1069–1076.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.020

- Winkel P, Hilden J, Fischer Hansen J, et al. Excess sudden cardiac deaths after short-term clarithromycin administration in the CLARICOR trial: why is this so, and why are statins protective? Cardiology. 2011;118(1):63–67. doi:10.1159/000324533

- Winkel P, Hilden J, Hansen JF, et al. Clarithromycin for stable coronary heart disease increases all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and cerebrovascular morbidity over 10 years in the CLARICOR randomised, blinded clinical trial. Int J Cardiol. 2015;182:459–465. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.01.020

- Gluud C, Als-Nielsen B, Damgaard M, et al. Clarithromycin for 2 weeks for stable coronary heart disease: 6-year follow-up of the CLARICOR randomized trial and updated meta-analysis of antibiotics for coronary heart disease. Cardiology. 2008;111(4):280–287. doi:10.1159/000128994

- Bachert C, Han JK, Desrosiers M, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (LIBERTY NP SINUS-24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS-52): results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group Phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019;394(10209):1638–1650. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31881-1

- Han JK, Bachert C, Fokkens W, et al. Mepolizumab for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (SYNAPSE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(10):1141–1153. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00097-7

- Gevaert P, Omachi TA, Corren J, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in nasal polyposis: 2 randomized phase 3 trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(3):595–605. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.032

- Colclasure JC, Gross CW, Kountakis SE. Endoscopic sinus surgery in patients older than sixty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131(6):946–949. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2004.06.710

- Ramadan HH, VanMetre R. Endoscopic sinus surgery in geriatric population. Am J Rhinol. 2004;18(2):125–127. doi:10.1177/194589240401800210

- Jiang RS, Hsu CY. Endoscopic sinus surgery for the treatment of chronic sinusitis in geriatric patients. Ear Nose Throat J. 2001;80(4):230–232. doi:10.1177/014556130108000411

- Krings JG, Kallogjeri D, Wineland A, Nepple KG, Piccirillo JF, Getz AE. Complications of primary and revision functional endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(4):838–845. doi:10.1002/lary.24401

- Gardner JR, Campbell JB, Daigle O, King D, Kanaan A. Operative and postoperative outcomes in elderly patients undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(5):1471–1476. doi:10.1007/s00405-020-06453-2

- Reh DD, Mace J, Robinson JL, Smith TL. Impact of age on presentation of chronic rhinosinusitis and outcomes of endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21(2):207–213. doi:10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3005

- Lehmann AE, Scangas GA, Sethi RKV, Remenschneider AK, El Rassi E, Metson R. Impact of age on sinus surgery outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(12):2681–2687. doi:10.1002/lary.27285

- Helman SN, Carlton D, Deutsch B, et al. Geriatric sinus surgery: a review of demographic variables, surgical success and complications in elderly surgical patients. Allergy Rhinol. 2021;12:21526567211010736. doi:10.1177/21526567211010736

- Lee JY, Lee SW. Influence of age on the surgical outcome after endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(6):1084–1089. doi:10.1097/MLG.0b013e318058197a

- Shin JM, Byun JY, Baek BJ, Lee JY. Cellular proliferation and angiogenesis in nasal polyps of young adult and geriatric patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(6):541–546. doi:10.1002/alr.21506

- Brescia G, Barion U, Pedruzzi B, et al. Sinonasal polyposis in the elderly. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2016;30(5):153–156. doi:10.2500/ajra.2016.30.4349

- Brescia G, Marioni G, Franchella S, et al. Can a panel of clinical, laboratory, and pathological variables pinpoint patients with sinonasal polyposis at higher risk of recurrence after surgery? Am J Otolaryngol. 2015;36(4):554–558. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2015.01.019

- Kim DW, Kim DK, Jo A, et al. Age-related decline of neutrophilic inflammation is associated with better postoperative prognosis in non-eosinophilic Nasal Polyps. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148442. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148442

- Wen W, Liu W, Zhang L, et al. Increased neutrophilia in nasal polyps reduces the response to oral corticosteroid therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(6):1522–1528.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.079

- Brescia G, Marioni G, Franchella S, et al. A prospective investigation of predictive parameters for post-surgical recurrences in sinonasal polyposis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(3):655–660. doi:10.1007/s00405-015-3598-5

- Vlaminck S, Vauterin T, Hellings PW, et al. The importance of local eosinophilia in the surgical outcome of chronic rhinosinusitis: a 3-year prospective observational study. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28(3):260–264. doi:10.2500/ajra.2014.28.4024

- Min JY, Kim YM, Kim DW, et al. Risk model establishment of endoscopic sinus surgery for patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: a multicenter study in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(40):e264. doi:10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e264

- Weilbach C, Scheinichen D, Thissen U, Jaeger K, Heine J, Piepenbrock S. [Anaesthesia in cataract surgery for elderly people]. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 2004;39(5):276–280. German. doi:10.1055/s-2004-814436

- Wormald PJ, van Renen G, Perks J, Jones JA, Langton-Hewer CD. The effect of the total intravenous anesthesia compared with inhalational anesthesia on the surgical field during endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol. 2005;19(5):514–520. doi:10.1177/194589240501900516

- Rhinology: KA. Sinus surgery in the older patient. Oper Tech Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2020;31(3):186–191. doi:10.1016/j.otot.2020.07.002

- Chaaban MR, Baillargeon JG, Baillargeon G, Resto V, Kuo YF. Use of balloon sinuplasty in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis in the United States. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017;7(6):600–608. doi:10.1002/alr.21939

- Viera-Artiles J, Corriols-Noval P, López-Simón E, González-Aguado R, Lobo D, Megía R. In-office endoscopic nasal polypectomy: prospective analysis of patient tolerability and efficacy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(12):3341–3348. doi:10.1007/s00405-020-06196-0

- Rudmik L, Soler ZM, Mace JC, Schlosser RJ, Smith TL. Economic evaluation of endoscopic sinus surgery versus continued medical therapy for refractory chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(1):25–32. doi:10.1002/lary.24916

- Klimek L, Koennecke M, Mullol J, et al. A possible role of stem cells in nasal polyposis. Allergy. 2017;72(12):1868–1873. doi:10.1111/all.13221

- Cho KS, Kim YW, Kang MJ, Park HY, Hong SL, Roh HJ. Immunomodulatory effect of mesenchymal stem cells on T lymphocyte and cytokine expression in Nasal Polyps. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(6):1062–1070. doi:10.1177/0194599814525751

- Pezato R, de Almeida DC, Bezerra TF, et al. Immunoregulatory effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the Nasal Polyp Microenvironment. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:1–11. doi:10.1155/2014/583409

- Yang C, Li J, Lin H, Zhao K, Zheng C. Nasal mucosa derived-mesenchymal stem cells from mice reduce inflammation via modulating immune responses. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0118849. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118849

- Trombitaș VE, Nagy AA, Berce C, et al. The role of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of a chronic rhinosinusitis-An in vivo mouse model. Microorganisms. 2021;9:6. doi:10.3390/microorganisms9061182