Abstract

Purpose

The multidimensional prognostic index (MPI) is a prognostic model derived from the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) which can predict 1-year mortality risk in elderly individuals. We hypothesized that the MPI also reflects the degree of frailty and thus will correlate with established measures of frailty. Therefore, the aim of this study is to explore whether the MPI-score is a measure of frailty in older head and neck cancer patients and is associated with several physical functioning measurements.

Patients and Methods

From November 2019 to July 2020, a prospective cohort study enrolled patients with head and neck cancer aged ≥70 years, and patients <70 years with an abnormal G8 score. The MPI-score ranged from 0 to 1 and was categorized in MPI-stage 1 (≤0.33, non-frail); MPI-stage 2 (0.34–0.66, mildly frail), and MPI-stage 3 (≥0.67, severe frail). Pearson’s correlation coefficient and multivariable linear regression were used to study the association between MPI-score and the physical functioning measurements handgrip strength, gait speed, and the timed up and go test (TUGT).

Results

A total of 163 patients were included. One hundred four (63.8%) patients were categorized as non-frail according MPI-stage 1, and 59 (36.2%) patients as mildly or severe frail (n=55 MPI-stage 2; n=4 MPI-stage 3, respectively). A higher MPI-score was significantly associated with lower hand grip strength (B −0.49 [95% CI −0.71; −0.28] p<0.001), lower gait speed (B −0.41 [95% CI −0.55; −0.25] p<0.001), and a slower TUGT (B 0.53 [95% CI 0.66; 0.85] p<0.001).

Conclusion

Almost one-third of the included patients with head and neck cancer was mild or severe frail. A higher MPI-score, indicating higher degree of frailty, was associated with worse physical performance by lower handgrip strength, gait speed, and a slower TUGT. Thus, the MPI reflects the degree of frailty.

Introduction

Head and neck cancers (HNC) represent the sixth most common cancer worldwide with approximately more than half a million new patients diagnosed annually. It accounts for about 3% of all cancers and especially affects older adults.Citation1 About 30% of adults with HNC are aged >70 years, while 10% are aged >80 years at diagnosis.Citation2,Citation3 The treatment for head and neck cancer can be surgery and/or (chemo)radiation. However, not every patient has enough resilience for intensive and/or invasive treatment. There is a lot of heterogeneity among elderly patients. Patients are heterogeneous regarding their functional, social, and cognitive functioning, resulting in different levels of resilience.Citation4 Patients with low resilience are frail, which is defined as having a reduced function and being at higher risk for health deterioration. Measuring the degree of frailty of the individual patient is crucial for patient selection and treatment decisions since frail patients have a high risk for adverse outcomes such as delirium, reduced quality of life, and mortality.Citation4,Citation5

To measure frailty, physical functioning measurements can be used such as handgrip strength and gait speed. Muscle strength and gait speed are core criteria for frailty and sarcopenia, and are recognized indicators of overall health.Citation6 High gait speed and handgrip strength are associated with better survival and less adverse health outcomes in the general population and in many disease-specific populations including head and neck cancer patients, also after surgical interventions.Citation7–Citation9

In clinical practice, the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) has become the internationally established method to assess older patients and to identify the degree of frailty.Citation10–Citation12 The CGA is performed by a geriatrician and focuses on multiple geriatric domains such as comorbidities, polypharmacy, nutritional status, functional status, social support, and psychological status.Citation13 By assessing these domains a tailored treatment plan can be made to improve treatment outcomes by eg prevention or reduction of perioperative complications. To translate the CGA findings in a numerical prognostic score, the Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI) has been developed.Citation14 The MPI consists of the domains cognition, functioning, medical and social parameters, and nutritional status. A higher MPI-score is associated with increased 1-year mortality, hospitalization or admission to a healthcare institution.Citation15–Citation20

The MPI, which was originally developed to predict mortality, has also been suggested as a frailty assessment model.Citation21,Citation22 However, whether the MPI-score reflect the degree of frailty has not been studied yet.

We hypothesize that a higher MPI-score reflects a higher degree of frailty and thus will associate with lower handgrip strength, gait speed, and timed up and go test (TUGT) scores. Therefore, the aim of this study is to explore whether the MPI is a measure of frailty in older head and neck cancer patients and is associated with several physical functioning measurements.

Materials and Methods

Patient and Study Design

This prospective single-center study enrolled consecutive patients from the 26th of November 2019 to the 27th of July 2020. Elderly patients with pathologically proven head and neck cancer were referred by the Department of Otorhinolaryngology of the Erasmus MC University Medical Center to the Geriatrics outpatient clinic for a CGA prior to anti-cancer treatment decision. Inclusion criteria were an age of 70 years or older, and pathologically proven head and neck cancer. Second, patients younger than 70 years were screened by a trained nurse with the Geriatric 8 (G8), an established and most frequently used frailty screening tool in geriatric oncology.Citation23,Citation24 Patients with a G8 score lower than 14 were referred for a CGA and included in this study as well. Patients provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus MC University Medical Center (MEC 2019-0711). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Definitions

Patient characteristics were assessed at study entry and retrieved from the patients’ medical history. Hypertension was defined as noted in history and/or when the patient used daily antihypertensive drugs. Diabetes mellitus type 2 was defined as noted in history or when the patient uses daily antidiabetic drugs. Chronic kidney disease was defined as a history of renal insufficiency and/or a serum creatinine above 140 mmol/L. Head and neck cancer was categorized in the following categories: skin, oral cavity, nasal cavity, sinonasal, salivary glands, oropharynx, nasopharynx, hypopharynx, larynx and unknown primary. Tumors were classified and defined according to the seventh edition of the Union for International Cancer Control TNM classification.Citation25 The World Health Organization (WHO) performance status is organized as followed: Grade 0 defined as no restriction and fully mobilized, Grade 1 restricted only in strenuous activity, Grade 2 capable of self-care and more than 50% of the time mobilized, Grade 3 limited self-care and more than 50% of the time immobilized and Grade 4 completely immobilized and not able to carry out any self-care.Citation26 Level of education was classified conform the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED 2011) and subdivided into five levels of education; early childhood and primary education (level 1, ISCED 0-1), lower secondary education (level 2, ISCED 2), upper secondary education (level 3, ISCED 3), post-secondary non-tertiary and short-cycle tertiary education (level 4, ISCED 4-5), and Bachelor’s, Master’s or Doctoral level (level 5, ISCED 6-8).Citation27

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

A CGA was performed assessing somatic, functional, psychological and social domains to map the main geriatric impairments, capacities, and needs for care. This included a thorough anamnesis containing the patients’ medical and psychiatric history, use of medication, socio-demographic status, and general complaints, and a physical examination. To evaluate the cognitive, physical and social functioning, and to estimate the MPI-score, several rating scales were used. Generally, the CGA lasted 60 to 90 minutes, and took place before a treatment advice was given by the multidisciplinary team of head and neck cancer.

Multidimensional Prognostic Index

The CGA was performed by geriatricians or residents under the supervision of a geriatrician. The MPI was calculated as described in previous studies, with a modification in the cognitive domain based on availability of data.Citation14–Citation16,Citation28,Citation29 The MPI consists of the domains cognition, functioning, medical and social parameters, and nutritional status. The MPI-score ranges from 0 to 1. Patients are categorized as having a low 1-year mortality risk (MPI-stage 1, score ≤ 0.33), versus a moderate (MPI-stage 2, score 0.34–0.66) and high (MPI-stage 3, score ≥ 0.67) 1-year mortality risk. The MPI involves the following questionnaires: Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE),Citation30 we used the MMSE instead of the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire, Exton-Smith Scale (ESS),Citation31 Katz’s Activities of Daily Living (KATZ ADL),Citation32 Lawton’s Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (Lawton IADL),Citation33 Cumulative Illness Rating Scale – Comorbidity Index (CIRS-CI)Citation34,Citation35 and Mini Nutritional Assessment – Short Form (MNA-SF).Citation36 Besides these questionnaires, the number of drugs used and living situation were recorded. Living situation was categorized in the following order: living with family, institutionalized and living alone. For each of the eight domains, a three-level score was assigned with score 0 indicating no problem, score 0.5 indicating a minor problem and score 1 indicating a severe problem, as established in previous studies.Citation14–Citation16 The categorization of each domain is shown in Table S1. The sum of all domain values was then divided by 8 to obtain the final MPI-score ranging between 0 and 1. A score between 0.00 and 0.33 was defined as MPI-stage 1, a score between 0.34 and 0.66 as MPI-stage 2, and a score between 0.67 and 1.00 as MPI-stage 3.

Physical Functioning Measures

Handgrip strength, gait speed, and the TUGT are established measures of physical functioning and of frailty. Handgrip strength was measured using the digital grip dynamometer (T.K.K. 5401; Takei Scientific Instruments Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). A patient was sitting upright in a chair with the shoulders in a neutral position, the elbow bent 90° and the forearm in neutral position of the hand to be measured. Instructions were given to squeeze as hard as possible. The measurement was performed two times for both left and right hand and the highest score was used for analysis. The cut-off value for men was <27 kilograms (kg) and for women <16 kg.Citation6 Gait speed was measured as the time someone needed to walk 5 meters from a standstill position and then into a comfortable pace. The measurement was performed twice and the highest score was used for the analysis. The cut-off value was ≤0.8 meters per second (m/s).Citation6 For the TUGT time was measured to stand up from a seated position on a chair without using the armrests, walk three meters as quickly and safely as possible, turn around, walk back to the chair and sit down. Walking aid was allowed if needed. The cut-off value for the TUGT was ≥20 seconds.Citation6

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables descriptive statistics were reported as mean with standard deviation (SD) or median with the interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were displayed as absolute numbers with percentage. Independent t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used for continuous variables. The Independent t-test was used for normally distributed variables and the Mann–Whitney test was used for non-normally distributed variables. The Chi-squared test was used for categorical variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlation between the MPI and physical functioning measurement. Multivariable linear regression was used to study the association between MPI and physical functioning measurement. Model 1 was performed crude, and model 2 adjusted for age and sex. Model assumptions were checked. We checked the assumptions of linear regression modelling, ie, multicollinearity, homoscedasticity, and the distribution of the residuals. P-values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (version 25; Corp. Armonk, New York).

Results

Enrollment and Patients Characteristics

A total of 172 patients with head and neck cancer were referred by the department of head and neck surgery for a CGA. A CGA was not performed in 2 patients and 7 patients did not provide informed consent. A total of 163 patients were included in this study (), of whom nineteen (11.7%) of the patients were younger than 70 years. The majority of patients was men (68.7%) with a median age of 76 years (). Most patients were living with family (68.1%). Almost half of the cohort was diagnosed with hypertension (49.7%). The most common head and neck tumor site was the oral cavity (22.1%), followed by the larynx (20.2%) and oropharynx (15.3%). The majority of the patients (63.6%) did not have any pathological regional lymph nodes, and 97% did not have distant metastasis.

Table 1 Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Head and Neck Cancer, Further Specified According MPI Category

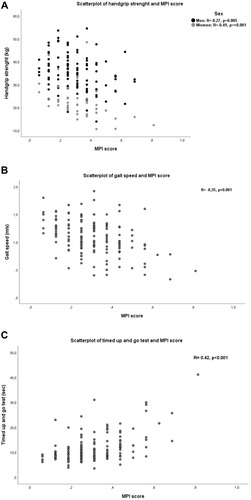

Figure 1 Scatter plots of the correlation between MPI-score and (A) Hand grip strength, (B) Gait speed, and (C) Timed Up and Go Test. (A) Men are displayed as circles and women as squares. Data incomplete for: Handgrip strength (men: N=110, women: N=49), Gait speed (N=154), Timed Up and Go Test (N=157).

MPI and Association with Physical Functioning Measurements

Of the 163 patients, 104 (63.8%) were classified as MPI-stage 1, 55 (33.7%) as MPI-stage 2, and 4 (2.5%) as MPI-stage 3. For the analyses, MPI-stage 2 and 3 were merged due to the small number in MPI-stage 3. Compared to MPI-stage 2 and 3, patients with MPI-stage 1 had less comorbidity including less myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus type 2, COPD or asthma and chronic kidney disease (). Age was not significantly different between MPI-stage 1 versus MPI-stage 2 and 3. Patients in MPI-stage 2 and 3 more often used a walking aid compared to MPI-stage 1 (30 (50.8%) vs 11 (10.6%), p=<0.001). Handgrip strength was significantly higher for men and women in MPI-stage 1 compared to MPI-stage 2 and 3 patients. Gait speed was significant faster (p<0.001) for MPI stage 1 (1.16 (±0.29) m/sec compared with MPI-stage 2 and 3 (0.96 ±0.32 m/sec). The TUGT was significantly slower (p<0.0001) in MPI-stage 2 and 3, (12.4 [IQR 8.8–18.0] seconds) compared to MPI-stage 1 (9.0 [IQR=7.7–11.2] seconds). Tumor-related characteristics did not differ significantly.

The MPI-score was negatively correlated with handgrip strength in men (R −0.27, p=0.005), and in women (R −0.49, p<0.001, ). Furthermore, a higher MPI-score was significantly correlated with a lower gait speed (R −0.35 (p< 0.001)) and a slower TUGT time (R 0.42 (p<0.001)) (). Using multivariate linear regression, a higher MPI score was significantly associated with lower hand grip strength (B −0.313 [95% CI −0.007; −0.002] p <0.001), gait speed (B −0.421 [95% CI −0.248; −0.121] p=0.001), and a higher TUGT (B 0.510 [95% CI 0.009; 0.016] p<0.001) after adjustment for age and sex ().

Table 2 Association Between MPI-Score and Physical Functioning Measurement

MPI Category and Treatment

Treatment strategy was different in patients with MPI-stage 1 versus MPI-stage 2 and 3. Patients in MPI-stage 1 more often received surgery, whereas MPI-stage 2–3 patients more often received palliative comfort care (). In addition, patients receiving chemo-radiation therapy were more often categorized as MPI-stage 2 and 3.

Comparison of Frailty Definitions

According to the MPI, 104 (63.8%) of the patients were classified as non-frail (MPI-stage 1), and 59 (36.2%) of the patients were classified as mildly or severe frail (MPI-stage 2 and 3). According the international cut-off values for handgrip strength, 142 (87.3%) of the patients were considered non-frail, and 21 (12.7%) of the patients were frail (Table S2). Using the gait speed cut-off value of ≤0.8m/s, 135 (83.1%) of the patients were classified as non-frail, and 28 (16.9%) of the patients were classified as frail. Finally, according the cut-off value of ≥20 sec for the TUGT, 151 (92.4%) of the patients were classified as non-frail, and 12 (7.6%) of the patients as frail.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that about one-third of this cohort was moderate to severe frail as assessed by the MPI. Individuals with a higher MPI-score, had lower muscle strength, lower gait speed, and a slower TUGT scores. Thus, the MPI indeed reflects the degree of frailty.

About one-third of the head and neck cancer patients in this study was frail according the MPI, and these patients more often received palliative treatment. Current literature shows that frailty is a predictor of perioperative outcomes such as mortality, perioperative complications, a greater length of hospital stay, readmission and with lower quality of life in head and neck cancer.Citation37,Citation38 With an aging population, the incidence of older patients with cancer and more complex comorbidities will also increase. Thus, physicians need to recognize frailty, and a CGA to further evaluate the degree of frailty is important to risk stratification and treatment decisions. The strength of the CGA-based MPI tool is that the MPI provides a numerical score and categorizes patients as having a low, moderate or high risk of death in 1 year according MPI-stage 1, stage 2 or stage 3, respectively. The strong association of the MPI-score with measures of physical function in this study strengthens the MPI as a tool to assess the degree of frailty.

To our best knowledge, this was the first study that investigated the associations of MPI-score with various measures of frailty. The MPI has been previously investigated in populations of patients with cancer. Three studies evaluated prediction of 1-year mortality risk by the MPI in patients with different types of cancers, namely in breast, lung, genitourinary and colorectal cancer.Citation17,Citation20,Citation39 First, the study of Giantin et al included patients with inoperable or metastatic solid cancer of the lung.Citation17 Thirty percent of those patients were classified as MPI-stage 2, and 10% as MPI-stage 3. Thus, more patients were categorized as MPI-stage 3 compared to our study (2.5%), whereas the percentage of MPI-stage 2 was quite similar (33.7%). An explanation might be that in our study patients with metastatic disease were not always not referred for a CGA. The two other studies included a mix of different tumor types and the MPI-staging of those cohort is only limited comparable to our findings. A considerable part of our cohort, namely one-third, was considered moderate to severe frail.

A large cohort of the Cardiovascular Health Study classified only 7% of their population as frail.Citation4 They used the Fried frailty phenotype definition, which focuses mainly on the physical abilities of a patient. However, the Cardiovascular Health Study included healthy individuals. The head and neck cancer population has a high prevalence of functional and cognitive impairment, depression, social isolation, and a low survival rate.Citation40,Citation41 The main reason for the relative high prevalence of frailty in our cohort could be the rate of comorbidity in this population.Citation42 More than 85% had three or more comorbidities. Besides, about 40% were at risk for developing malnutrition or were already malnourished. It is inherent to head and neck cancer, especially those tumors that are present in the oropharynx and oral cavity, that the tumor negatively affects the food intake. Malnutrition is an important contributor in the development of frailty and included in frailty definitions.Citation4

We found a relatively high prevalence of geriatric impairments further underscoring the vulnerability of the head and neck cancer population, and the higher biological age of this population. The prevalence of geriatric impairments is in accordance with previous studies A recent study of van Deudekom et al identified geriatric disabilities in elderly people with head and neck cancer in a Dutch population.Citation41 They included patients diagnosed with head and neck cancer stage III or IV, or a lower stage but needing invasive treatment. Their findings are quite similar; 14% were ADL dependent versus 7.3% in our study, and 10% were IADL dependent versus 8.0% in our study. The prevalence of malnutrition and use of a walking device was highly similar to our study, with 40% of the elderly being at risk of developing malnutrition or already malnourished, and 28% using a walking device.

Notably, the percentage of cognitive impairment was low in our study (7%, using the MMSE) compared to the other studies. First, the study of van Deudekom et al reported a prevalence of (25%, using the 6-Item Cognitive Impairment Test).Citation40 This difference could be explained by the difference in screening instruments or the difference in comorbidity. Second, a study by Williams et al described that 55% of the 83 adults with HNC before t were cognitively impaired. However, a large percentage of their population 60% was current drug user (marijuana, cocaine and heroin) in comparison to 2.4% current or past user in our study.Citation43 Furthermore, 35% of their patients received mental health treatment in comparison with 4.7% in our study. Both drug use and mental health problems could explain the high prevalence of cognitive impairment in their study. Nevertheless, using the screenings instrument MMSE we could have underestimated the prevalence of cognitive impairment. A study by Bond et al used an extended neuropsychological examination and reported prevalence of 23–36% for impairment in the various cognitive domains that were examined.Citation44 Since the neuropsychological examination is the gold standard, the MMSE screening in our study might have underestimated the prevalence of cognitive impairment.

Our cohort included a relatively high rate of 63.6% node-negative head and neck cancer patients. This high percentage can be explained by the fact that 20.2% of our cohort included patients with laryngeal cancer and 22.1% oral cavity cancer. These patients are often diagnosed and treated when they are still in an early stage of the cancer and thus often node-negative. Another notable finding was that patients receiving chemo-radiation therapy were more likely to be categorized as frail according MPI-stage 2 and 3. However, this finding should be interpreted cautiously, since it was a small subgroup of the cohort, and only patients aged <70 years receive chemotherapy in our center.

A major strength of this study is that we had several measures of frailty and a detailed CGA available in older adults with head and neck cancer. Furthermore, this is the first study evaluating the MPI in a cohort of head and neck cancer patients. There are also some limitations to address. First, this is a single-center study. Nevertheless, our results are relatively similar to findings from other studies. Second, since only few patients were categorized as MPI-stage 3, it might be that the frailest and/or terminal patients have not been referred for a CGA anymore. It would not only be invasive for these patient but also not contribute to their treatment. Third, our cohort included a heterogenic population with various (sub)sites of head and neck cancer, which have different characteristics and clinical course. The degree of frailty of the patients might be different according to the different tumor (sub)sites.

Future studies are needed to evaluate the predictive value of the MPI for 1-year mortality and morbidity in older head and neck cancer patients. In other cancer populations, the MPI was reported to improve the prediction of 1-year mortality, going beyond the traditional risk factors.Citation20 Furthermore, the MPI strongly associated with postoperative major complications in colorectal carcinoma patients, and turned out to be the most important variable in the prediction model.Citation45 It is currently unknown whether the MPI-score adds to the prognostic accuracy of existing prognostic tools in head and neck cancer, such as a recently published prediction score by Ruhle et al.Citation46 Furthermore, the prognostic value of the MPI could be compared to the prognostic value of the physical functioning measurements handgrip strength, gait speed, and the TUGT as well.Citation47,Citation48 Using MPI may provide a practical and comprehensive evaluation of patients, and help to optimize management and decision-making in vulnerable head and neck cancer patients.

In conclusion, almost one-third of the elderly patients with head and neck cancer was mildly or severe frail. A higher MPI-score, indicating a higher degree of frailty, was strongly associated with worse physical performance by lower handgrip strength, gait speed, and a slower TUGT. Thus, the MPI is able to identify the degree of frailty.

Abbreviations

ADL, Activities of daily living; BCC, Basal cell carcinomas; CGA, Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment; COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CIRS-CI, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale – Comorbidity Index; ESS, Exton-Smith Scale; IADL, Instrumental activities of daily living; IQR, median with the interquartile range; KATZ, Katz/s Activities of Daily Living; Lawton, Lawton’s Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Exam; MNA-SF, Mini nutritional Assessment-Short Form; MPI, Multidimensional Prognostic Index; NSTEMI, Non-ST-elevated myocardial infarction; SD, standard deviation; STEMI, ST-elevated myocardial infarction; TUGT, Timed-Up-and-Go-Test; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Erasmus Medical Center [MEC 2019-0711].

Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study design, acquisition of data, and article preparation; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all volunteers from the departments of Otorhinolaryngology and Oral and Maxillofacial surgery, and nurse consultants, former research students, and residents of the Division of Geriatrics at the Erasmus MC University Medical Center for their contribution to the study database.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ChowLQM. Head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):60–72.31893516

- FerroM, MacchiaG, ReA, et al. Advanced head and neck cancer in older adults: results of a short course accelerated radiotherapy trial. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(3):441–445.33097457

- SiegelRL, MillerKD, FuchsHE, JemalA. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33.33433946

- FriedLP, TangenCM, WalstonJ, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56.11253156

- RockwoodK, FoxRA, StoleeP, RobertsonD, BeattieBL. Frailty in elderly people: an evolving concept. CMAJ. 1994;150(4):489–495.8313261

- Cruz-JentoftAJ, BaeyensJP, BauerJM, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39(4):412–423.20392703

- ChainaniV, ShaharyarS, DaveK, et al. Objective measures of the frailty syndrome (hand grip strength and gait speed) and cardiovascular mortality: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2016;215:487–493.27131770

- LiuMA, DuMontierC, MurilloA, et al. Gait speed, grip strength, and clinical outcomes in older patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2019;134(4):374–382.31167800

- MeerkerkCDA, ChargiN, de JongPA, van den BosF, de BreeR. Low skeletal muscle mass predicts frailty in elderly head and neck cancer patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021. doi:10.1007/s00405-021-06835-0

- SolomonD, Sue BrownA, Brummel-SmithK, et al. Best paper of the 1980s: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: geriatric assessment methods for clinical decision-making 1988. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(10):1490–1494.14511174

- ExtermannM, AaproM, BernabeiR, et al. Use of comprehensive geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: recommendations from the task force on CGA of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG). Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;55(3):241–252.16084735

- CleggA, YoungJ, IliffeS, RikkertMO, RockwoodK. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–762.23395245

- de VriesJ, HeirmanAN, BrasL, et al. Geriatric assessment of patients treated for cutaneous head and neck malignancies in a tertiary referral center: predictors of postoperative complications. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46(1):123–130.31427138

- PilottoA, FerrucciL, FranceschiM, et al. Development and validation of a multidimensional prognostic index for one-year mortality from comprehensive geriatric assessment in hospitalized older patients. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11(1):151–161.18173367

- PilottoA, VeroneseN, DaragjatiJ, et al. Using the multidimensional prognostic index to predict clinical outcomes of hospitalized older persons: a prospective, multicenter, international study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(10):1643–1649.30329033

- PilottoA, AddanteF, FerrucciL, et al. The multidimensional prognostic index predicts short- and long-term mortality in hospitalized geriatric patients with pneumonia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(8):880–887.19349589

- GiantinV, ValentiniE, IasevoliM, et al. Does the Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI), based on a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), predict mortality in cancer patients? Results of a prospective observational trial. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(3):208–217.24070459

- GiantinV, FalciC, De LucaE, et al. Performance of the Multidimensional Geriatric Assessment and Multidimensional Prognostic Index in predicting negative outcomes in older adults with cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27:1.

- MeyerAM, SiriG, BeckerI, et al. The Multidimensional Prognostic Index in general practice: one-year follow-up study. Int J Clin Pract. 2019;73:e13403.

- LiuuE, HuC, ValeroS, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer: an external validation of the multidimensional prognostic index in a French prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):295.32811435

- DentE, KowalP, HoogendijkEO. Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: a review. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;31:3–10.27039014

- WarnierRM, van RossumE, van VelthuijsenE, MulderWJ, ScholsJM, KempenGI. Validity, reliability and feasibility of tools to identify frail older patients in inpatient hospital care: a systematic review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(2):218–230.26812520

- BelleraCA, RainfrayM, Mathoulin-PelissierS, et al. Screening older cancer patients: first evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(8):2166–2172.22250183

- SoubeyranP, BelleraC, GoyardJ, et al. Screening for vulnerability in older cancer patients: the ONCODAGE Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115060.25503576

- SobinLH, GospodarowiczMK, WittekindC. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 7th ed. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.

- OkenMM, CreechRH, TormeyDC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649–655.7165009

- UNESCO. Institute for Statistics: International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 2011. Montréal; 2012.

- BureauML, LiuuE, ChristiaensL, et al. Using a multidimensional prognostic index (MPI) based on comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) to predict mortality in elderly undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2017;236:381–386.28238508

- AnglemanSB, SantoniG, PilottoA, FratiglioniL, WelmerAK, InvestigatorsMAP. Multidimensional prognostic index in association with future mortality and number of hospital days in a population-based sample of older adults: results of the EU funded MPI_AGE project. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133789.26222546

- FolsteinMF, FolsteinSE, McHughPR. Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198.1202204

- BlissMR, McLarenR, Exton-SmithAN. Mattresses for preventing pressure sores in geriatric patients. Mon Bull Minist Health Public Health Lab Serv. 1966;25:238–268.6013600

- KatzS, FordAB, MoskowitzRW, JacksonBA, JaffeMW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of Adl: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919.14044222

- LawtonMP, BrodyEM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186.5349366

- LinnBS, LinnMW, GurelL. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16(5):622–626.5646906

- ConwellY, ForbesNT, CoxC, CaineED. Validation of a measure of physical illness burden at autopsy: the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(1):38–41.8418120

- RubensteinLZ, HarkerJO, SalvaA, GuigozY, VellasB. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(6):M366–m372.11382797

- FuTS, SklarM, CohenM, et al. Is frailty associated with worse outcomes after head and neck surgery? A narrative review. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(6):1436–1442.31633817

- de VriesJ, BrasL, SidorenkovG, et al. Frailty is associated with decline in health-related quality of life of patients treated for head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2020;111:105020.33045628

- BrunelloA, FontanaA, ZafferriV, et al. Development of an oncological-multidimensional prognostic index (Onco-MPI) for mortality prediction in older cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(5):1069–1077.26758276

- van DeudekomFJ, SchimbergAS, KallenbergMH, SlingerlandM, van der VeldenLA, MooijaartSP. Functional and cognitive impairment, social environment, frailty and adverse health outcomes in older patients with head and neck cancer, a systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2017;64:27–36.28024721

- van DeudekomFJ, van der VeldenLA, ZijlWH, et al. Geriatric assessment and 1-year mortality in older patients with cancer in the head and neck region: a cohort study. Head Neck. 2019;41(8):2477–2483.30816619

- DatemaFR, FerrierMB, van der SchroeffMP, Baatenburg de JongRJ. Impact of comorbidity on short-term mortality and overall survival of head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 2010;32(6):728–736.19827120

- WilliamsAM, LindholmJ, CookD, SiddiquiF, GhanemTA, ChangSS. Association between cognitive function and quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(12):1228–1235.29121151

- BondSM, DietrichMS, MurphyBA. Neurocognitive function in head and neck cancer patients prior to treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(1):149–157.21229270

- PataG, BianchettiL, RotaM, et al. Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI) score has the major impact on outcome prediction in elderly surgical patients with colorectal cancer: the FRAGIS study. J Surg Oncol. 2021;123(2):667–675.33238052

- RuhleA, StrombergerC, HaehlE, et al. Development and validation of a novel prognostic score for elderly head-and-neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy or chemoradiation. Radiother Oncol. 2021;154:276–282.33245947

- IshiiR, OgawaT, OhkoshiA, NakanomeA, TakahashiM, KatoriY. Use of the geriatric-8 screening tool to predict prognosis and complications in older adults with head and neck cancer: a prospective, observational study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021. doi:10.1016/j.jgo.2021.03.008

- ChargiN, BrilSI, Emmelot-VonkMH, de BreeR. Sarcopenia is a prognostic factor for overall survival in elderly patients with head-and-neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276(5):1475–1486.30830300