Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of circuit-based exercise on the body composition in obese older women by focusing on physical exercise and body weight (BW) gain control in older people.

Methods

Seventy older women (>60 years old) voluntarily took part in the study. Participants were randomized into six different groups according to body mass index (BMI): appropriate weight (AW) control (AWC) and trained (AWT) groups, overweight (OW) control (OWC) and trained (OWT) groups, and obesity (O) control (OC) and trained (OT) groups. The exercise program consisted of 50 minutes of exercise three times per week for 12 weeks. The exercises were alternated between upper and lower body using rest between sets for 40 seconds with intensity controlled by heart rate (70% of work). The contraction time established was 5 seconds to eccentric and concentric muscular action phase. The following anthropometric parameters were evaluated: height (m), body weight (BW, kg), body fat (BF, %), fat mass (FM, kg), lean mass (LM, kg), and BMI (kg/m2).

Results

The values (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) of relative changes to BW (−8.0% ± 0.8%), BF (−21.4% ± 2.1%), LM (3.0% ± 0.3%), and FM (−31.2% ± 3.0%) to the OT group were higher (P < 0.05) than in the AWT (BW: −2.0% ± 1.1%; BF: −4.6% ± 1.8%; FM: −7.0% ± 2.8%; LM: 0.2% ± 1.1%) and OWT (BW: −4.5% ± 1.0%; BF: −11.0% ± 2.2%; FM: −16.1% ± 3.2%; LM: −0.2% ± 1.0%) groups; additionally, no differences were found for C groups. While reduction (P < 0.03) in BMI according to absolute values was observed for all trained groups (AWT: 22 ± 1 versus 21 ± 1; OWT: 27 ± 1 versus 25 ± 1, OT: 34 ± 1 versus 30 ± 1) after training, no differences were found for C groups.

Conclusion

In summary, circuit-based exercise is an effective method for promoting reduction in anthropometrics parameters in obese older women.

Introduction

In older adults, age-related changes contribute to alterations in body composition such as increases in fat mass (FM) and decreases in lean mass (LM) and loss of height caused by compression of vertebral bodies and kyphosis.Citation1 Additionally, the prevalence of obesity (O) has increased among older adults and will likely continue to increase.Citation2

Therefore, weight gain worsens age-related impairment of physical function and often leads to frailty and is frequently associated to sarcopenia. These changes in body composition, low muscle mass, and/or low muscle strength may coexist in the same person, a condition defined as sarcopenic O. This condition may induce a decrease in the level of physical activity, reducing the most important trophic effect on muscle mass as well as predisposing adults to positive energy balance and FM gain. Moreover, excess adiposity is a strong contributing factor for cardiovascular disease risk.Citation3

Exercise training (ET) has been shown to be an effective non-pharmacological method to reduce body weight (BW) and physical disability in obese older people; moreover, ET has been considered a primary strategy for reducing cardiovascular disease risk and inducing weight loss through reduced daily energy intake and moderate endurance exercise.Citation4

It is well-established that ET improves the physical capacity of obese people,Citation5,Citation6 and therefore, physical activity should be increased among this group. Obese people are a challenging group for physical activity promotion as they have more comorbidities and physical impairments and they report an increased number of diseases compared to their non-obese age peers, such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and osteoarthritis, smaller muscle strength relative to body mass, pain, and tiredness.Citation7 Basic exercise guidelines recommended by the American College of Sports Medicine for healthy adults and elderly people emphasize that training programs should consist of resistance, strength, aerobic, and flexibility exercises.

However, the shortage or interruption in body composition changes in exercise programs may be determinants of withdrawal, so in order to structure weight loss programs more effectively it is important to develop methods of physical training that effectively awaken changes in body composition. Among the most varied methods, resistance training has been applied in the form of circuit training (CT). Using this exercise protocol to change the body composition in overweight (OW) adults, Fett et alCitation8 demonstrated that training caused decreases in BW and FM; however, no effects were demonstrated by Dias et alCitation9 on anthropometric parameters after CT.

There is no information available to describe the effect of CT in obese older women. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the impacts of circuit-based exercise on body composition in obese older women.

Materials and methods

Subjects

After receiving approval from the Healthy Institute (015–2010) ethics committee, 90 healthy older women were recruited from the regional community adult day care facilities focusing around the School of Arts, Sciences, and Humanities of the University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. All participants voluntarily took part in the study, received medical examinations, and filled in questionnaires regarding their medical history. All procedures in this study conformed to the 196/96 resolution of the Brazilian Ministry of Health and the Helsinki Human Rights Declaration (http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/ ). Only those who gave written informed consent were included in the research.

Inclusion criteria to this study were being ≥60 years of age, healthy, and physically independent. Exclusion criteria were as follows: participation in current or previous regular exercise training in the last 6 months, recent hospitalization, symptomatic cardiorespiratory disease, severe hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and renal or hepatic disease, cognitive impairment or progressive and debilitating conditions, marked O with inability to exercise, recent bone fractures, or any other medical contraindications to training.

The classification of O was established according to the body mass index (BMI) by the World Health OganizationCitation10 and is of use in the Brazilian population.Citation11 Thus three levels were determined: appropriate weight (AW; 18.5–24.9 kg/m2); overweight (OW; 25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (O; >30.0 kg/m2).

According to the exclusion criteria, 12 women were excluded and 78 women were randomized into six groups, including AW control (AWC, n: 9) and trained (AWT, n: 20) groups, OW control (OWC, n: 10) and OW trained (OWT, n: 14) groups, and O control (OC, n: 9) and trained (OT, n: 16) groups. Subjects that could not frequent the training sessions on the program days were considered as the control group. Participation in <90% of the stipulated exercise program was also considered as an exclusion criteria. All groups maintained their usual daily activities. All subjects were instructed to keep their previously controlled normal dietary intake, to inform the study directors of any new prescribed medication, and to not take part in any other type of physical exercise.

Body composition

Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a Cardiomed stadiometer (WCS model, Cardiomed, Curitiba, Brazil). Body mass was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a Filizola scale (Personal Line 150 model, Filizola, São Paulo, Brazil). BMI (kg/m2) was calculated as follows: BMI = weight/height2. Body composition was determined using anthropometric measures.Citation11 Each skinfold was measured three times to the nearest 0.1 cm using a Lange skinfold caliper (Sanny Scientific Skinfold Caliper, São Paulo, Brazil) and the mean value was used for calculations. Body fat (BF) percentage was derived with skinfolds as was done previously by our group.Citation12 The following parameters were evaluated: BW, BF, LM, FM, and BMI.

Circuit-based exercise program

The exercise program consisted of 50-minute exercise sessions three times per week on nonconsecutive days for 12 weeks. After 5 minutes of aerobic warm-up performed on a treadmill, the following isotonic exercises were performed in a circuit: knee flexion, arm raise, shoulder abduction, shoulder adduction, shoulder rotation, squat, biceps curl, triceps extensions, calves raise, push-up, abdominal crunch, and hip extension. All participants were encouraged to accomplish the exercise movement within 45 seconds. Weight resistance was performed using elastic bands and free weights; contraction time was 5 seconds for eccentric and concentric phases followed by rest for 40 seconds. In order to allow a proper familiarization with the exercises with the correct and safe technique of execution and breathing, training intensity was lower during the first three sessions. After this period, the exercise intensity (70%) was controlled based on the individual preprogrammed target heart rate previously calculated using the Karvonem equation: % of work × (maximal heart rate - baseline heart rate) + baseline heart rate, corrected for resting heart rate on the day of the exercise and monitored in all participants during training sessions by Polar-HR monitors (S150; São Paulo, Brazil). To minimize fatigue, the exercise was alternated between upper and lower body exercises. Rest was used between sets of 40 seconds, but there were no pauses between repetitions. Each session was guided by trained fitness instructors and supervised by the researchers.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows software (version 12.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The D’Agostino–Pearson test was applied for Gaussian distribution analysis. Analysis of comparisons between groups along the time periods were performed using two-way analysis of variance with repeated measures, followed by Kruskal–Wallis or Bonferroni’s post hoc tests when appropriated. Comparisons between groups concerning relative changes in variables after training were performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Kruskal–Wallis or Bonferroni’s post hoc tests when appropriate. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05.

Results

During the research period, no one left the study; however, two and seven women in the AWT and OT groups, respectively, participated in <90% of the physical activity program. Therefore, our data are based on 69 subjects: (AWC, n = 9) and (AWT, n = 18) groups, (OWC, n = 10) and (OWT, n = 14) groups and (OC, n = 9) and (OT, n = 9) groups.

During and after training, no participants suffered injuries as a result of the training programs. shows the anthropometrics parameters of all groups. At baseline, the values of BW, BF, FM, LM, and BMI of the O groups did not differ; however, the values were higher than in the AW and OW groups. Additionally, no differences were found between the respective control to AWT and OWT groups.

Table 1 Anthropometrics measures

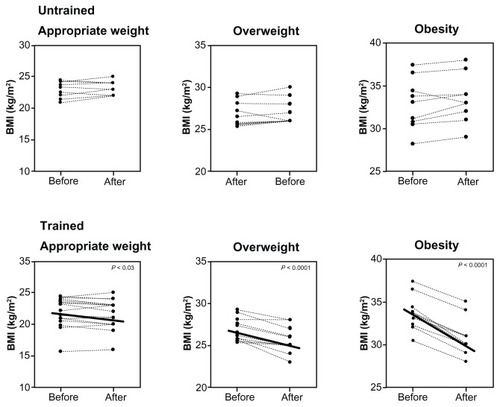

For all analyzed parameters in the AWT group, there was no significant difference in the values before versus after training and AWC; however, in the OWT and OT groups, the values of BW, BF, FM, and BMI were lower than the baseline values and respective controls. However, only the OT group showed an increase in LM after training ().

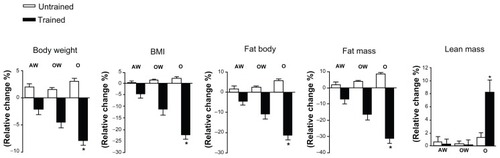

The relative changes are showed in . Changes of values in BW (−8.0% ± 0.8%), BF (−21.4% ± 2.1%), LM (8.0% ± 2%), and FM (−31.2% ± 3.0%) in the OT group were higher (P < 0.05) than in the AWC (BW: 2.0% ± 0.4%; BF: 1.6% ± 1.5%; LM: 0.6% ± 0.6%; FM: 2.0% ± 1.5%), AWT (BW: −2.0% ± 1.1%; BF: −4.6% ± 1.8%; LM: 0.2% ± 1.1%; FM: −7.0% ± 2.8%), OWC (BW: 1.5% ± 0.3%; BF: 2.5% ± 0.3%; LM: 0.3% ± 0.4%; FM: 4.0% ± 0.4%), OWT (BW: −4.5% ± 1.0%; BF: −11.0% ± 2.2%; LM: −0.2% ± 1.0%; FM: −16.1% ± 3.2%), and OC (BW: 3.0% ± 0.5%; BF: 6.0% ± 1.0%; LM: 1.3% ± 0.7%; FM: 9.0% ± 0.8%) groups. No differences were found among other groups.

Figure 1 Repercussion (means ± standard error) of appropriate weight (AW), overweight (OW), and obesity (O) groups from baseline in body weight, body fat, lean mass, fat mass, and body mass index (BMI).

Although a significant (P < 0.03) reduction in BMI () was found in all trained groups (AWT: 22 ± 1 versus 21 ± 1, kg/m2; OWT: 27 ± 1 versus 25 ± 1, kg/m2; OT: 34 ± 1 versus 30 ± 1, kg/m2) after training (), no differences were found in control groups (AWC: 23 ± 5 versus 23 ± 4, kg/m2; OWC: 26 ± 1 versus 27 ± 1, kg/m2; OC: 33 ± 1 versus 33 ± 1, kg/m2). Additionally, the relative change in BMI () in trained groups (AWT: −5% ± 2%; OWT: −1% ± 3%; OT: −22% ± 2%) was higher than in control groups (AWC: 1% ± 1%; OWC: 2% ± 1%; OC: 2% ± 1%). Furthermore, the decrease in values of the OT group was statistically (P < 0.05) stronger than other groups.

Discussion

This is the first study to assess the effects of 12 weeks of circuit-based exercise on obese older women. According to our results, circuit-based exercise is effective for promoting reductions in anthropometrics parameters, particularly the increase in LM.

The prevalence of OW people is a serious public health concern, and is a risk factor for developing cardiovascular and metabolic disorders.Citation13,Citation14 Thus, there is a need to identify effective therapeutic practices for regulating BW and improving quality of life.

An appropriate level of physical activity has direct effects on the maintenance of lean body mass in adults.Citation14 Therefore, treatment strategies for O, which maximize the BF loss and increase LM, carry significant benefits to obese people.Citation15–Citation17 The ET plays an important role in weight control and is often associated with other types of interventions such as diet. However, several studiesCitation18–Citation22 showed similar results presented in this paper without dietary control to modify body composition, particularly free FM. In addition, the weight loss achieved with moderate physical activity can be easily reversed by a small compensatory increase in food intake.Citation23

Additionally, aging often leads to a loss of functional fitness in older people, reducing their ability to perform daily tasks.Citation19–Citation21,Citation24 Moreover, fall-related injuries are serious problems in old age, as they often lead to prolonged, or even permanent, disability. Therefore, maintenance of LM is frequently considered an important strategy for improving functional fitness, preventing BW gain, reducing disability,Citation25 improving the quality of life, and reducing the costs of health care. Moreover, a review of randomized controlled trials has demonstrated that exercise reduces the risk of falls in elderly people, and reduction in the incidence of fall-related injuries is related to lower health care costs.Citation26 The preservation of functional capacity, muscle strength and BW, prevention of injuries that reduce disability, improvement of quality of life, and reduction of costs of health care should be the most relevant features of exercise programs. The contribution of ET in general for the weight loss process is due to the increase in daily caloric expenditure promoted by the fat-free mass, as found in our study. Additionally, the ET energy expenditure may also stimulate elevation of basal metabolic rate due to increased muscle mass. It is believed that the tendencies of people to gain weight with age are due largely to a reduced basal metabolic rate by progressive LM loss.Citation27

Not surprisingly, strength exercises can substantially modify the body composition and capacity of power generation in different populations.Citation28 In relationship to CT, the effectiveness is unclear, with studies showing positiveCitation8,Citation29 and discordant resultsCitation9,Citation30 in adults and old people. However, clinically, our results are important for future research, specifically for sarcopenic subjects. The loss of muscle mass reduces targets available to insulin-responses, promoting insulin resistance, in turn promoting metabolic syndrome and O.Citation31–Citation35 Moreover, increasing FM promotes production of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, and other adipokines that further promote insulin resistance as well as potentially having a direct catabolic effect on muscle reducing the muscle strength. Villareal et alCitation36 suggest that sarcopenic O is a major public health problem; in this perspective, circuit-based exercise is considered cheaper and a reliable method for preventing sarcopenic status.

Additionally, it is known that one factor contributing to the failure of the treatment of O is maintaining a low-calorie diet intake for long periods, causing demotivation.Citation37 An important feature of ET is that it allows the possibility of a large number of people taking part in exercise sessions. This fact corresponds to the wide variety of exercise as well as the increased possibility of intrapersonal relationships with exercise practice, leading to higher level of motivation during training.

There were some limitations to this study. This was a relatively small sample study, and it was not designed to examine possible biochemical mechanisms of bone adaptation to exercise programs.

In conclusion, we demonstrated the positive effects of circuit strength training on body composition parameters, and relevant importance should be given to improve LM in obese older women. For future therapeutic considerations, the present work may support the safety and utility of this exercise modality for larger trials, as well as for education and physical training in this population.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to Fárlley Rodrigues for assistance with language correction and layout of this article.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SorkinJDMullerDCAndresRLongitudinal change in height of men and women: implications for interpretation of the body mass index: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of AgingAm J Epidemiol1999150996997710547143

- ArterburnDECranePKSullivanSDThe coming epidemic of obesity in elderly AmericansJ Am Geriatr Soc200452111907191215507070

- VillarealDTApovianCMKushnerRFObesity in older adults: technical review and position tatement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity SocietyAm J Clin Nutr200582592393416280421

- KaplanNMThe deadly quartet. Upper-body obesity, glucose intolerance, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypertensionArch Intern Med19891497151415202662932

- KosterAPenninxBWNewmanABLifestyle factors and incident mobility limitation in obese and non-obese older adultsObesity (Silver Spring)200715123122313218198323

- LangIAGuralnikJMMelzerDPhysical activity in middle-aged adults reduces risks of functional impairment independent of its effect on weightJ Am Geriatr Soc200755111836184117979901

- BaumgartnerRNWayneSJWatersDLSarcopenic obesity predicts instrumental activities of daily living disability in the elderlyObes Res200412121995200415687401

- FettCAFettWCROyamaSRMarchiniJSBody composition and somatotype in overweight and obese women pre- and post-circuit training or joggingRev Bras Med Esporte20061214550

- DiasRPrestesJManzattoREffects of different exercise programs in clinic and functional status of overweight womenBrazilian J Kinanthrom Human Performance2006835865

- World Health OrganizationObesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultationWorld Health Organ Tech Rep Ser2000894ixii1253

- TaveresELAnjosLAAnthropometric profile of the elderly Brazilian population: results of the National Health and Nutrition Survey, 19891999154759768

- BocaliniDSSerraAJdos SantosLMuradNLevyRFStrength training preserves mineral bone density in postmenopausal women without use of hormone replacement therapyJ Aging Health200921351952719252142

- KumanyikaSKObarzaneckEStettlerNPopulation-based prevention of obesityCirculation200811842846418591433

- Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. The Evidence ReportNational Institutes of HealthObes Res19986Suppl 251S209S9813653

- BrinerRWUllrichIHSauresJEffects of aerobic vs resistance training combined with an 800 calorie liquid diet on lean body mass and resting metabolic rateJ Am Col Nutr1999182115121

- JakicicJMOttoADPhysical activity considerations for the treatment and prevention of obesityAm J Clin Nutr200582Suppl 1226S229S16002826

- StieglerPCunliffeAThe role of diet and exercise for maintenance of fat free mass and rest metabolic rate during weight lossSports Med200636323926216526835

- DeibertPKönigDVitolinsMZEffect of a weight loss intervention on anthropometric measures and metabolic risk factors in pre-versus postmenopausal womenNutr J20076313717961235

- HillJOSchlundtDGSbroccoTEvaluation of an alternating-calorie diet with an without exercise in the treatment of obesityAm J Clin Nutr19895022482542667313

- SarisWHMExercise with or without dietary restriction and obesity treatmentInt J Obes199519Suppl 4781787

- KraemerWJVolekJSClarkKLPhysiological adaptations to a weight loss dietary regimen and exercise programs in womenJ Appl Physiol19978312702799216973

- RossRPedwellHRissanenJEffects of energy restriction and exercise on skeletal muscle and adipose tissue in women as measured by magnetic resonance imagingAm J Clin Nutr1995616117911857762515

- BallorDLPoehlmanETExercise-training enhances lean mass preservation during diet-induced weight loss: a meta-analytical findingInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord199418135408130813

- GrundySMBlackburnGHigginsMLauerRPerriMGRyanDPhysical activity in the prevention and treatment of obesity and its comorbitiesMed Sci Sports Exerc199931Suppl 11S502S50810593519

- GarrowJSSummerbellCDMeta-analysis: effect of exercise, with or without dieting, on the body composition of overweight subjectsEur J Clin Nutr19954911107713045

- BroadwinJGoodman-GruenDSlymenDAbility of fat and lean mass percentages to predict functional disability in older men and womenJ Am Geriatric Soc2001491216411645

- GardnerMMRobertsonMCCampbellAJExercise in preventing falls and fall related injuries in older people: a review of randomized controlled trialsBr J Sports Med200034171710690444

- HallalPCVictoraCGWellsJCLimaRCPhysical inactivity: prevalence and associated variables in Brazilian adultsMed Sci Sports Exerc200335111894190014600556

- MaioranaAO’DriscollGDemboLGoodmanCTaylorRGreenDExercise training, vascular function, and functional capacity in middle-aged subjectsMed Sci Sports Exerc200133122022202811740294

- GarciaJMSSánchezEDLCGarcíaADSGonzálezYEPilesSTInfluence of a circuit-training programme on health-related fitness and quality of life in sedentary women above 70 years oldFit Perf2007611419

- WinettRACarpinelliEDPotential health-related benefits of resistance trainingPrev Med200133550351311676593

- AllisonDBGallagherDHeoMPi-SunyerFXHeymsfieldSBBody mass index and all-cause mortality among people age 70 and over: the Longitudinal Study of AgingInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord19972164244319192224

- WalkerRFEditor’s choice: sarcopenia or loss of muscle massClin Interv Aging2012713914122791986

- HeberDInglesSAshleyJMMaxwellMHLyonsRFElashoRMClinical detection of sarcopenic obesity by bioelectrical impedance analysisAm J Clin Nutr199664Suppl 3S472S477

- ReavenGMBanting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human diseaseDiabetes19883712159515973056758

- VillarealDBanksMSienercCSinacoreDKleinSPhysical frailty and body composition in obese elderly men and womenObes Res2004126912919

- BronsteinMDObesity and physical exerciseRev SOCESP199661111115