Abstract

Background/aims

This study assesses and compares prevalence of psychological and behavioral symptoms in a Belgian sample of people with and without dementia.

Methods

A total of 228 persons older than 65 years with dementia and a group of 64 non-demented persons were assessed using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) in 2004.

Results

Within the group without dementia, the most frequent symptoms were depression, agitation, and irritability. Within the group with dementia, the most common symptoms were depression, irritability, apathy, and agitation. Prevalence of delusions (P < 0.05), hallucinations (P < 0.05), anxiety (P < 0.05), agitation (P < 0.05), apathy (P < 0.01), aberrant motor behavior (P < 0.01), and eating disorders (P < 0.05) were significantly higher in the group with dementia.

Conclusion

Depression, elation, irritability, disinhibition, and sleeping disorders are not specific to dementia. Agitation, apathy, anxiety, and delusions are more frequent in dementia but were not specific to the dementia group because their prevalence rates were close to 10% in the group without dementia. Hallucinations, aberrant motor behavior, and eating disorders are specific to dementia. The distinction between specific and nonspecific symptoms may be useful for etiological research on biological, psychological, and environmental factors.

Introduction

Noncognitive manifestations in dementia have been described in many studies.Citation1 Since the 1980s, systematic studies have revealed how important these manifestations are in dementia symptomatology; they have been shown to constitute early signs of dementia and may even precede the onset of cognitive deficits.Citation2,Citation3 They also have a considerable impact on the daily lives of patientsCitation4 and their caregivers.Citation5,Citation6 Numerous assessment tools have been developed to assess and analyze these noncognitive manifestations.Citation7–Citation9 In 1996, the International Psychogeriatric Association defined noncognitive manifestations of dementia as “signs and symptoms of disturbed perception, thought content, mood, or behavior that frequently occur in patients with dementia.”Citation10 Furthermore, a distinction was made between behavioral and psychological signs and symptoms. Behavioral symptoms are identified by observing patients in their living environment. They include aberrant motor behavior, agitation/aggression, irritability, disinhibition, apathy, and sleeping and eating disorders. Psychological symptoms are mainly noticed during the clinical interview with the patient or by the caregivers. They consist of mood disorders (anxiety, depression, and euphoria) and psychotic signs (delusion, hallucination, and illusion).

Prevalence estimates for the presence of psychological or behavioral symptoms among demented patients (BPSD) range from 61% to 88%.Citation11,Citation12 This variability is often greater for specific symptoms. For example, the prevalence rates for agitation reportedly vary from 29% to 87% among patients with dementia.Citation13,Citation14 The variability between studies is likely related to methodological differences (eg, nature and characteristics of the sample, definitions of disorders, and assessment instruments) as well as to data collection modalities (eg, evaluator’s status) and life conditions of the subjects (eg, home, institution, or hospital). Apathy and agitation constitute the most common behavioral symptoms,Citation15–Citation17 while psychological symptoms are particularly represented by depression, anxiety, and delusions.Citation13,Citation17,Citation18 Only one study has examined prevalence rates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Belgian patients.Citation19 This study included patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, mixed dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies. Patients were assessed using the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (Behave-AD),Citation20 with the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI)Citation7 and Middelheim Frontality Score (MFS).Citation21 This study showed that aggressiveness and activity disturbances are the most common symptoms among people with dementia. Some studies compare these symptoms between people with and without dementia;Citation12,Citation15,Citation18 however, at present, no comparative study of Belgian people with and without dementia has been carried out.

Studies on the nature and prevalence of behavioral and psychological symptoms observed among elderly non-demented subjects (“cognitively impaired non-demented” [CIND], “mild cognitive impairment” [MCI]), without characterized cerebral pathology would be interesting. These studies could be used to distinguish between symptoms appearing mainly in people without dementia and those that are shared by both populations (ie, people both with and without dementia). This distinction is likely to argue in favor of different etiological hypotheses. An examination of etiological factors is furthermore important for the selection and implementation of treatment.

This study had three aims: (1) to assess the nature and prevalence of psychological and behavioral symptoms in a Belgian sample of people with and without dementia; (2) to compare our data with that of previous studies; and (3) to compare the prevalence of behavioral and psychological symptoms between people with and without dementia.

Materials and methods

Population

A sample of 223 persons with dementia (D) and a group of 46 persons without dementia (ND) were selected in the context of the Qualidem study.Citation22 Qualidem was a Belgian study examining dementia and had three aims: (1) to realize an inventory of existing information based on an exhaustive review of scientific and gray literature; (2) to develop recommendations for qualitative and humanitarian care; and (3) to assess tools and procedures selected during a field study. Qualidem protocol has been validated by Belgium’s National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (NIHDI), the financing body of the study. The current study explored secondary data from the Qualidem report. We analyzed data from subjects who took part in the Qualidem study and for whom we had sociodemographic, diagnostic, state of health, and Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) data. Inclusion criteria for the Qualidem study were people older than 65 who were institutionalized or had been receiving home care for at least 1 month up to the time of the study and those with specific characteristics (brief hospitalization in a general or psychiatric hospital; consultations repeated by a doctor; demand of a particular financial intervention to the Belgian social security system; demand for home adjustments; complaint concerning cognitive capacities; suspicion of dementia formulated by the health care professional). A three-step diagnostic procedure was used for clinical diagnosis. In the first stage, as recommended in De Lepeleire,Citation23 subjects were assessed with both the Activities of Daily LivingCitation24 and the Instrumental Activities of Daily LivingCitation25 in order to detect those with high sensitivity cognitive losses. In the second and third stages, more specific diagnostic testing was performed, which included the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)Citation26 and CAMDEX-RCitation27 in order to select subjects with dementia (ie, those with an MMSE score < 24 and a CAMCOG score < 70). Identification of different types of dementia was not made. Establishment of these diagnostics requires additional clinical and paraclinical examination. The ND group was made up of subjects having some cognitive and/or functional disabilities without meeting the full DSM IV criteriaCitation28 for dementia. Based on clinical assessment and the results from CAMDEX-R, subjects with delirium were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained from each subject or his/her representative.

Instruments

All subjects were assessed with the NPI.Citation8 This instrument is specifically used to evaluate neuropsychiatric symptoms among persons with dementia. NPI is an informant-based rating scale; an experienced professional completes the survey in conjunction with a formal or informal caregiver. NPI evaluates 12 common psychological and behavioral symptoms in dementia, including delusions, hallucinations, agitation/ aggression, depression, anxiety, elation, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, aberrant motor behavior, and sleeping and eating disorders. For each neuropsychiatric symptom, there is a screening question to determine if the symptom has been present or absent within the past month. For positive responses, scripted questions are asked in order to confirm the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms. If the presence is confirmed, further questions are then asked concerning the frequency (on a scale from 1 to 4) and severity (on a scale from 1 to 3) of the symptom. The reliability and validity of NPI were demonstrated by Cummings.Citation29 Interrater reliability ranged from 93.6% to 100%, depending on the subdomain. Test–retest reliability was also shown to be very high (r [20] = 0.79). In addition, content validity was shown to be high, as rated by 10 internationally known experts in geriatric psychiatry.

Data collection

The data were collected in the subject’s place of residence (in their home or in one of 25 different institutions) by either the family caregiver (at home), or health centers (in the institution) in collaboration with the researchers.

Results

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistica 7.0 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK) and included the following techniques:

Student’s t-test (adjusted for unequal variances) to compare clinical and demographic characteristics between the two groups and to control the impact of health status and age on the presence of BPSD.

Mann–Whitney U test to compare the frequency and severity criteria between the two groups for each NPI domain.

Chi-square statistics (χ2 tests) and contingence coefficient (CC) to compare prevalence of BPSD and sex repartition between the two groups.

Characteristics of the sample

shows demographic and clinical characteristics of the study groups. Of the total patients, 81% were female, 83% lived in a long-term-care institution, and 17% lived at home. Significant group differences between the ND and D groups were found for age, health status, MMSE total score, and CAMCOG total score. The ND group was younger and had higher total scores on both the MMSE and the CAMCOG. For each NPI domain, the effects of health and age on the presence of symptoms were controlled. No significant result emerged from these analyses.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical data

NPI data

A total of 20.9% of subjects in the D group (53/223 subjects) and 56.5% (26/46 subjects) in the ND group did not present any symptoms.

Data from NPI domains are presented according to International Psychogeriatric Association classifications.Citation10 Within the D group, the most frequent psychological symptom was depression (27.8%; n = 62), followed by anxiety (23.8%; n = 53) and delusions (22.9%; n = 51). A total of 16.1% (n = 36) of the D group exhibited hallucinations. Prevalence of elation was low (11.8%; n = 26). In the ND group, the most common disorder was depression (19.6%; n = 9). In contrast, prevalence rates of anxiety (8.7%; n = 4), delusions (6.5%; n = 3), and elation (8.7%; n = 4) were distinctly lower. Finally, hallucinations were reported in only two subjects (4.35%).

Prevalence of delusions, hallucinations, and anxiety were significantly higher in the D group than in the ND group (). There were no significant differences between the groups concerning depression and elation. Frequency and severity of depression were significantly higher in the D group than in the ND group. There were no differences in frequency and severity of other psychological symptoms.

Table 2 Prevalences of NPI symptoms in groups

Within the D group, the most frequent behavioral symptom was apathy (35%; n = 78), followed by agitation/ aggression (34.1%; n = 76) and irritability (29.1%; n = 65). Symptoms in aberrant motor behavior (21.5%; n = 48), disinhibition (14.3%; n = 32), eating disorders (22.9%; n = 51), and sleeping disorders (15.2%; n = 35) were also found often. In the ND group, there was a high prevalence of irritability (17.4%; n = 8) and agitation (17.4%; n = 8). Prevalence of apathy (11%; n = 5) and disinhibition (8.7%; n = 4) were lower. Finally, sleeping disorders (6.5%; n = 3), eating disorders (6.5%; n = 4), and aberrant motor behavior (4.3%; n = 2) were rarely reported in the ND group.

Prevalence of agitation, apathy, aberrant motor behavior, and eating disorders were significantly higher in the D group (). There were no significant differences between groups regarding disinhibition, sleeping disorders, and irritability. Frequency scores of apathy, irritability, and sleeping disorders were higher in the D group. There were no differences concerning the frequency of other behavioral symptoms. Severity scores of apathy and irritability were higher in the D group.

Discussion

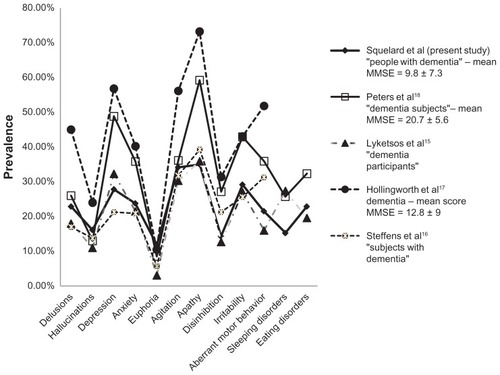

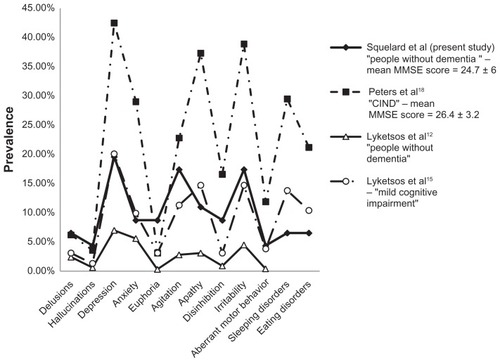

The main goals of this study were to assess the nature and prevalence of psychological and behavioral symptoms in a Belgian sample of people with and without dementia and to compare prevalence of behavioral and psychological symptoms between both populations. Within the dementia group, depression, anxiety, and delusions constituted the most frequent psychological symptoms (from 20% to 30%) (). Elation was less common (<12%). Regarding behavioral symptoms, agitation/aggression (34.1%), apathy (35%), and irritability (30%) were reported among a third of people with dementia. Prevalence rates for other NPI symptoms varied from 10% to 23%. Within the group without dementia, depression was the most common psychological symptom (19.5%) (). Prevalence rates of anxiety, delusions, and elation were between 6% and 9%. Hallucinations were infrequent (<5%). Regarding behavioral symptoms, irritability and agitation/aggression were the most common symptoms (15%). Prevalence rates for disinhibition and apathy were approximately 10%. Aberrant motor behavior and sleeping and eating disorders were rare (close to 5%). Comparative analysis showed that prevalence rates of depression, elation, irritability, disinhibition, and sleeping disorders did not differ significantly between groups. Delusions, hallucinations, anxiety, apathy, agitation/aggression, aberrant motor behavior, and eating disorders were significantly more frequent in the dementia group. In the dementia group, only the frequencies of apathy, irritability, and sleeping disorders were higher. Regarding severity criteria, the scores were higher in the dementia group for apathy and irritability.

Within the dementia group, data distribution is similar to that in previous studiesCitation15–Citation18 (). However, we observed quantitative differences between our data and those from Hollingworth et alCitation17 and Peters et al,Citation18 whose prevalence rates were much higher than ours (). The sample included in the study by Hollingworth et alCitation17 included 1120 individuals “diagnosed with late-onset probable AD [Alzheimer’s disease].” Their results are higher than those from other NPI studies.Citation15–Citation18 The group of persons with dementia in Peters et alCitation18 included 576 subjects whose average MMSE score was clearly higher, and whose average age was lower, than our group of patients with dementia. This elicits a question of possible evaluator-related bias. Indeed, it is possible that some psychological symptoms are more easily detectable among people presenting with minor cognitive disorders than among those presenting with severe cognitive disorders. This hypothesis has not been investigated. Our high percentage of institutionalized dementia subjects could also explain these differences. Using the Behave-AD,Citation20 the MFS,Citation21 and the CMAI,Citation7 Engelborghs et alCitation19 noted the importance of aggressiveness, activity disturbance, and disinhibition in dementia semiology. Their prevalence rates were also higher than those presented here. The variability between this study and our current investigation is likely related to methodological differences, as well as variation in life conditions, of the subjects (eg, home, institution, hospital).

Regarding the group without dementia, data distribution is similar to that in previous studiesCitation12,Citation15,Citation18 (). However, Peters et alCitation18 reported higher prevalence rates than those shown in previous studies, except for elation and delusions (). Their sample contained 193 CIND subjects taken from “a Canadian cohort study of cognitive impairment and related dementias.”Citation18 According to these authors, an explanation for these high rates may have emerged within their definition of CIND. In another study, Lyketsos et alCitation12 studied 673 elderly subjects without dementia who were living at home or in an institution. Their observed prevalence rates were much lower than those in our study (). This variability is likely related to various factors, such as demographic and clinical characteristics and size, as well as life conditions of the evaluated populations. Moreover, the changing nature of the examined symptoms is likely to explain part of this variability.

Regarding comparative analysis, Lyketsos et alCitation12 showed that all NPI symptoms were significantly more frequent in their dementia group than in their non-dementia group, except for sleeping and eating disorders, which were not assessed. The heterogeneity of reported data may be due to the use of distinct procedures for subject selection and to the nature of the assessed population. Despite the fact that our results are roughly similar to those of Lyketsos et al,Citation15 this study also found that all NPI symptoms are significantly more frequent in their dementia group than in their MCI group, except for elation. This may be explained by the difference between the size of our group without dementia and their MCI group. Peters et alCitation18 found similar results to ours except for anxiety (no significant difference) and disinhibition.

This comparative analysis suggests a categorization of NPI symptoms. Some disorder prevalence rates did not significantly differ between groups (ie, depression, elation, irritability, disinhibition, and sleeping disorders). This report suggests that these symptoms are nonspecific to dementia. Prevalence rates of others NPI symptoms (ie, delusions, hallucinations, anxiety, agitation/aggression, apathy, aberrant motor behavior, and eating disorders) are significantly higher in the dementia group. Among these symptoms, some are rarely reported in the group without dementia (ie, hallucinations, delusions, aberrant motor behavior, and sleeping and eating disorders), with prevalence rates close to 5%. As a result, these symptoms can be considered specific to dementia, with prevalence rates ranging between 15% and 25% of the subjects with dementia. The other symptoms are more frequent in the dementia group, but have been regularly reported in the group without dementia with prevalence rates close to 10%. These symptoms are not specific to the dementia group. Nevertheless, it is important to note that some studies have reported prevalence rates of hallucinations () and aberrant motor behavior () as being lower than 5% among persons without dementia. Data concerning eating disorders are more heterogeneous.

Comparative analysis allows us to suggest a distinction between three categories of symptoms: dementia-specific symptoms, symptoms more frequent in dementia, and symptoms nonspecific to dementia. This distinction may be useful when examining etiological factors. Indeed, it may be hypothesized that dementia-specific symptoms are very likely associated with neurobiological factors. However, symptoms that are more frequent in dementia and symptoms that are nonspecific to dementia may be related to a variety of environmental, psychological, neurobiological, and somatic factors, the respective weights of which may be variable from one disorder to another and from one subject to another. The multifactorial etiology of some psychological and behavioral symptoms should have a direct impact on the nature of the interventions on patients with dementia and their families.

Thus, based on these hypotheses, a neurobiological approach would be more appropriate when examining the etiological basis of delusions, hallucinations, aberrant motor behavior, and sleeping and eating disorders. Conversely, a biopsychosocial approach would be more advisable to study depression, irritability, elation, sleeping disorders, anxiety, disinhibition, agitation/aggression, and apathy. The statement that these symptoms are often observed among subjects with other severe somatic pathologyCitation30–Citation33 is consistent with the multifactor causality hypotheses. However, since these hypotheses are inconsistent with those of previous studies,Citation34–Citation36 they must be verified by further research. More precise comparison of the symptomatology of disorders between people with and without dementia should give some indication of whether our hypothesis is correct.

Limitations of the study

The small size of the non-dementia group constitutes a primary limitation of our study. Second, inclusion criteria in both groups were not sufficiently precise. Third, we did not differentiate dementia by type in D group. Fourth, neither group was homogeneous regarding age and sex; additional analyses have been conducted to control for the influence of these factors on the presence/absence of NPI symptoms; the results supported our hypothesis. Fifth, subjects’ pharmacological treatment was not controlled: some substances could have induced psychological and behavioral disorders; other substances can reduce, alleviate, or eliminate some symptoms, and the influence of pharmacotherapy on psychological and behavioral symptoms should be the subject of further studies. Sixth, information concerning the durations of dementia had not been collected.

The NPI assessment tools also had some limitations: information obtained from an informant may have been influenced by his/her expectations and by his/her capacity to deal with critical situations. Patient–proxy assessment is the subject of debate in the literature.Citation37,Citation38 Thus, the results must be interpreted according to the definition of symptoms induced by the NPI. Indeed, some NPI domains include either specific symptoms such as hallucinations or highly heterogeneous syndromes such as aberrant motor behavior. Aberrant motor behavior includes various symptoms, such as intrusive behavior,Citation39 vocally disruptive behavior,Citation40 dyskinesia,Citation41 and ritualized behavior,Citation42 all of which involve different etiological factors.

Conclusion

We assessed the nature and prevalence of psychological and behavioral symptoms in populations of demented and non-demented people. In both groups, depression was the most common psychological disorder. Among behavioral symptoms, irritability was most prevalent in the non-dementia group and agitation/aggression was the most common in the dementia group. Comparative analysis revealed a distribution of symptoms in three categories: (1) those specific to dementia; (2) those whose prevalence was higher in dementia; and (3) those nonspecific to dementia. This distinction may prove useful for etiological research and for identifying adequate treatments. In order to better identify etiological factors, future studies should define different symptoms included in certain NPI domains more accurately.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by Belgium’s National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (NIHDI). This work was funded by RIZIV/INAMI “Studie dementia/Etude démence” UB/1240. The authors thank Mr Christophe Labiouse and Maurane Crespin for support in development of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- EsquirolJEDDes Maladies MentalesMental DisordersParisBaillière1838 French

- RubinEHKinscherfDAMorrisJCPsychopathology in younger versus older persons with very mild and mild dementia of the Alzheimer typeAm J Psychiatry199315046396428465883

- SeeleyWWBauerAMMillerBLThe natural history of variant frontotemporal dementiaNeurology20056481384139015851728

- SternYTangMXAlbertMSPredicting time to nursing home care and death in individuals with Alzheimer’s diseaseJAMA1997277108068129052710

- DonaldsonCTarrierNBurnsADeterminants of carer stress in Alzheimer’s diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry19981342482569646153

- MatsumotoNIkedaMFukuharaRCaregiver burden associated with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in elderly people in the local communityDement Geriatr Cogn Disord200723421922417299264

- Cohen-MansfieldJMarxMSRosenthalASA description of agitation in a nursing homeJ Gerontol1989443M77M842715584

- CummingsJLMegaMGrayKRosenberg-ThompsonSCarusiDAGornbeinJThe Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementiaNeurology19944412230823147991117

- TariotPNMackJLPattersonMBThe Behavior rating Scale for Dementia of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s DiseaseAm J Psychiatry19951529134913577653692

- FinkelSICosta e SilvaJCohenGMillerSSartoriusNBehavioral and psychological signs and symptoms of dementia: a consensus statement on current knowledge and implications for research and treatmentInt Psychogeriatr1996834975009154615

- MegaMSCummingsJLFiorelloTGronbeinJThe spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s diseaseNeurology19964611301358559361

- LyketsosCGSteinbergMTschanzJTNortonMCSteffensDCBreitnerJCMental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the cache county study on memory in agingAm J Psychiatry2000157570871410784462

- AaltenPde VugtMELousbergRBehavioral problems in dementia: a factor analysis of the neuropsychiatric inventoryDement Geriatr Cogn Disord20031529910512566599

- HauptMKurzAJännerMA 2-year follow-up of behavioral and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer’s diseaseDement Geriatr Cogn Disord200011314715210765045

- LyketsosCGLopezOJonesBFitzpatrickALBreitnerJDeKoskySPrevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Results from the Cardiovascular Health StudyJAMA2002288121475148312243634

- SteffensDCMaytanMHelmsMJPlassmanBLPrevalence and clinical correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementiaAm J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen200520636737316396442

- HollingworthPHamshereMLMoskvinaVFour components describe behavioral symptoms in 1120 individuals with late-onset Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Am Geriatr Soc20065491348135416970641

- PetersKRRockwoodKBlackSECharacterizing neuropsychiatric symptoms in subjects referred to dementia clinicsNeurology200666452352816505306

- EngelborghsSMaertensKNagelsGNeuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: cross-sectional analysis from a prospective, longitudinal Belgian studyInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200520111028103716250064

- ReisbergBBorensteinJSalobSPFerrisSHFranssenEGeorgotasABehavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: phenomenology and treatmentJ Clin Psychiatry198748511361139

- De DeynPPEngelborghsSSaerensJThe Middelheim Frontality Score: a behavioral assessment scale that discriminates frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry2005201707915578673

- PaquayLDe LepeleireJShoenmakersBThe Qualidem project in Belgium. A two-center study on care needs and provision in dementia care: inclusion criteria and description of the populationArch Public Health200462125142

- De LepeleireJDe diagnose van dementie. Het aandeel van de huisartsThe diagnosis of dementia The role of the general practitioner [doctoral thesis]LeuvenKatholieke Universiteit Leuven2000

- KatzSFordABMoskowitzRWJacksonBAJaffeeMWStudies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychological functionJAMA196318591491914044222

- LawtonMBrodyEAssessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrument activities of daily livingGerontologist19691931791865349366

- FolsteinMFFolsteinFSMc HughPR“Mini mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res19751231891981202204

- RothMTymEMountjoyC-QCAMDEXA standardised instrument for the diagnosis of mental disorders in the elderly with special reference to the elderly detection of dementiaBr J Psychiatry19861496987093790869

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th ed (DSM IV)Washington, DCAPA1997

- CummingsJLThe Neuropsychiatric Inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patientsNeurology19974861016

- KrishnanKRRDelongMKraemerHComorbidity of depression with other medical diseases in the elderlyBiol Psychiatry200252655958812361669

- CankurtaranMHalilMYavuzBBDagliNCankurtaranESAriogulSDepression and concomitant diseases in a Turkish geriatric outpatient settingArch Gerontol Geriatrics2005403307314

- KangasMHenryJLBryantRAThe course of psychological disorders in the 1st year after cancer diagnosisJ Consult Clin Psychol200573476376816173866

- GoldenSHLeeHBSchreinerPJDepression and type 2 diabetes mellitus: the multiethnic study of atherosclerosisPsychosom Med200769652953617636146

- MintzerJEUnderlying mechanisms of psychosis and aggression in patients with Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Clin Psychiatry200162Suppl 21232511584984

- ZubenkoGSNeurobiology of major depression in Alzheimer’s diseaseInt Psychogeriatr2000121217230

- TekinSMegaMSMastermanDMOrbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex neurofibrillary tangle burden is associated with agitation in Alzheimer diseaseAnn Neurol200149335536111261510

- MagazinerJSimonsickEKashnerTMHebelJRPatient-proxy response comparability on measure of patient health and functional statusJ Clin Epidemiol19884111106510743204417

- EpsteinAMHallJATognettiJSonLHConantLJrUsing proxies to evaluate quality of life. Can they provide valid information about patients’ health status and satisfaction with medical care?Med Care198927Suppl 3S91S982921889

- HopeTKeeneJGedlingKCooperSFairburnCJacobyRBehavior changes in dementia 1: Point of entry data of prospective studyInt J Geriatr Psychiatry19971211106210739427090

- WhallALGillisGLYankouDBoothDEBeel-BatesCADisruptive behaviorJ Gerontol Nursing199218101317

- LajeunesseCVilleneuveATardive dyskinesia. After more than 2 decadesEncephale19891554714852574103

- SinhaDZelmanF-PNelsonSA new scale for assessing behavioral agitation in dementiaPsychiatry Res199241173881561290