Abstract

Falls and fractures are major causes of morbidity and mortality in older people. More importantly, previous falls and/or fractures are the most important predictors of further events. Therefore, secondary prevention programs for falls and fractures are highly needed. However, the question is whether a secondary prevention model should focus on falls prevention alone or should be implemented in combination with fracture prevention. By comparing a falls prevention clinic in Manizales (Colombia) versus a falls and fracture prevention clinic in Sydney (Australia), the objective was to identify similarities and differences between these two programs and to propose an integrated model of care for secondary prevention of fall and fractures. A comparative study of services was performed using an internationally agreed taxonomy. Service provision was compared against benchmarks set by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and previous reports in the literature. Comparison included organization, administration, client characteristics, and interventions. Several similarities and a number of differences that could be easily unified into a single model are reported here. Similarities included population, a multidisciplinary team, and a multifactorial assessment and intervention. Differences were eligibility criteria, a bone health assessment component, and the therapeutic interventions most commonly used at each site. In Australia, bone health assessment is reinforced whereas in Colombia dizziness assessment and management is pivotal. The authors propose that falls clinic services should be operationally linked to osteoporosis services such as a “falls and fracture prevention clinic,” which would facilitate a comprehensive intervention to prevent falls and fractures in older persons.

Introduction

Falls and fractures are intimately linked and are major causes of morbidity and mortality in older people. Previous fall and/or fracture are the most important risk factor for further events;Citation1 therefore, secondary prevention programs for falls and fractures are highly needed. Although falls clinics have been established as a model of care for falls management and prevention among the elderly, there is not a widely accepted definition or standard model for a falls clinic in the research literature. Falls clinics have been defined as:

… specialist multidisciplinary services, which focus on the assessment and management of clients with falls, mobility and balance problems. Clinics commonly provide time limited, specialist intervention to the client and advice and referral to mainstream services for ongoing management. They provide education and training to clients, to carers, and to health professionals.Citation2

Since the late 1980s, falls clinics have been gaining momentum as an integrated model for falls prevention around the world. The first multidisciplinary falls clinic was set up in Melbourne, Australia in 1988.Citation2 Subsequently, the number of falls clinics has increased substantially since the late 1990s including Australia,Citation1–Citation4 USA,Citation5–Citation8 UK,Citation9 France,Citation10 Denmark,Citation11 Spain,Citation12 Hong Kong,Citation13 Canada,Citation14 Germany,Citation15 and The Netherlands.Citation16 In contrast, in Latin America the information related to falls clinics is scarce with reports only from Brazil and Colombia.Citation17,Citation18

Overall, these programs offer a comprehensive assessment and varied interventions focused on falls prevention in older persons without taking into consideration bone health assessment. In fact, until 2000 it was a common practice not to include any assessment to evaluate osteoporosis risk or to perform bone mineral density in falls prevention trials. As a consequence, osteoporosis risk assessment was not considered as part of a major falls prevention guideline.Citation19

In 2001, the National Health Service in the UK established the National Service Framework for Older People, a comprehensive strategy to ensure fair, high quality, integrated health and social care services for older people. The National Service Framework set out standards for specialized and integrated falls services to improve care and treatment for those who have fallen and, for the first time, included interventions to prevent and treat osteoporosis in those at high risk. Following these guidelines, there was an increasing understanding of the natural association between falls and fractures and thus a proposal to incorporate a routine bone health assessment as part of a comprehensive assessment for falls and fractures risk in older persons was suggested.Citation20 However, little operational guidance was provided until a review and clinical guideline undertaken by the National Health Service policy body, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), was published in 2004.Citation21 In those guidelines, NICE suggested that specialist falls services should be operationally linked to bone health (osteoporosis) services and recommended that an osteoporosis risk assessment should be an essential element of a comprehensive falls assessment.Citation21 Since the release of these guidelines, the number of falls clinics that integrates a bone health component has grown exponentially, particularly at university hospitals.Citation13,Citation14,Citation16 However, standardizing these programs and making them efficient in different cultures and practices is still a challenge. Another remaining question is whether the model should remain as falls prevention alone or should be combined with fracture prevention. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify similarities and differences between a falls and a falls and fractures clinic in Colombia and Australia, respectively. Characteristics of the services were compared using an internationally agreed taxonomy. Here, major similarities as well as easy to unify variations between these complementary models implemented in the two countries are reported.

Methods

In Sydney, Australia the Falls and Fractures Clinic at Nepean Hospital in Penrith began operation in October 2008 as an initiative of both the Discipline of Geriatric Medicine at Sydney Medical School Nepean and the Department of Geriatric Medicine at Nepean Hospital. Its primary aim was to reduce falls and falls-related injuries among older people in the Western Sydney community after suffering one or multiple falls and/or fractures. In Manizales, (Colombia) the Falls, Dizziness, and Vertigo Clinic at the local Geriatric Hospital was implemented in April 2001 as an initiative of the Section of Geriatric Medicine of the Faculty of Health at the University de Caldas. In addition to the aim of reducing falls among older people in the Andes Mountains community, this clinic’s aim was to ameliorate dizziness symptoms in older fallers.

The analysis was designed to explore and compare the organizational structure and clinical operations of both clinics. Evaluated items were either taken from prior research on Australian falls clinicsCitation2 or were developed specifcally for this study with emphasis on falls and fracture assessment and care of patients. The questionnaire assessed characteristics of organization, administration, clients, and interventions provided at both clinics. Items that surveyed program organization included: date of commencement, setting of recruitment and assessment, frequency and duration of each assessment session, and referral sources. Administration items surveyed the number of attended patients, number of staff, staffing structure, time for initial assessment, waiting time for service, and percentage of attrition. The age, proportion of men and women, and eligibility criteria were surveyed to compare the clients in the two countries. Directors were asked to indicate the process of assessment and reassessment procedures and the types of intervention provided. In addition, data was collected on risk status identification, outcomes measured, and postintervention follow-up procedures. It also assessed whether interventions were provided by the local service or by referral to other services, referral routes, and relationships to other local facilities and services. To make the comparison easier and to develop a common language to compare the characteristics of the clinics, the Prevention of Falls Network Europe (ProFaNE) taxonomy of falls prevention interventions was used.Citation24 The implementation of NICE recommendations was also compared.

Results

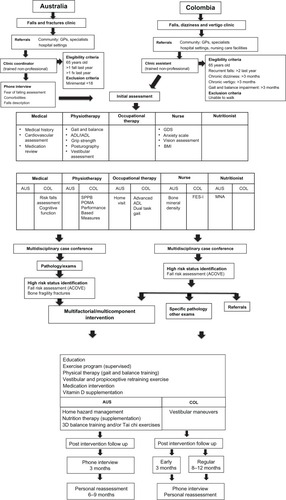

A summary of organization, administration, clients, and interventions at both clinics is shown in . Concerning organization aspects, the setting was an acute hospital in Australia and a subacute Geriatric hospital in Colombia. The programs in the two countries operated with the same frequency and duration (4 hours per week). The most common method of entry into the service was a referral from a health care professional: a general practitioner in Australia and a specialist (geriatrician, physiatrist, otolaryngologist, and rheumatologist) in Colombia. In addition, both services accepted referrals from acute hospitals, although mostly from emergency department and orthopedic/geriatric wards in Australia. In Colombia, referrals from nursing care facilities were also accepted.

Table 1 Comparison of organization, administration, client, and intervention characteristics

The number of clients attending the program and the number of patients attending per week was higher in the Australian program than in Colombia (average number of six versus three patients per session). In terms of staff, clinical staff in Australia was twice that in Colombia. However, in both clinics the staffing structure was a multidisciplinary team composing of a physiotherapist, nurse, occupational therapist, and a physician. At both clinics, members of the interdisciplinary team were engaged in discussions related to assessment tools and program planning over 1-year period prior to the establishment of the corresponding clinic. The mean length of the initial assessment was similar at both clinics (2 hours per patient). The waiting list was much longer in Colombia than in Australia. The percentage of attrition was similar in the two countries. The mean age of clients was higher in Australia than in Colombia (82 versus 74 years). There were similar proportions of men and women attending the clinics with at least two-thirds being female. The main eligibility criteria for Australian clients were falls and/or fractures (at least one episode in the previous year), whereas for Colombian clients the criteria were a report of falls and/or dizziness. In terms of interventions provided, there were similar practices with multicomponent interventions being used in both countries. Although both programs offered similar care plans in terms of falls prevention, the Australian program was more likely to prescribe vitamin D supplementation while the Colombian program was more likely to indicate individual supervised gentle balance exercises at home.

shows the comparative fow diagram for the two countries. By comparison, the Australian program was directed at managing falls and fractures while the Colombian program was focused on managing dizziness and falls. A similar proportion of disciplines was included in the multidisciplinary assessment team and similar assessment tools were employed. While the Australian program included bone health assessment, the Colombian program included more comprehensive fall risk screening tools in their assessment. The initial assessment at both clinics consists of a comprehensive fall risk assessment, including a structured algorithm adapted from the Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) intervention to identify risk factors for falls.Citation23 Recommendations for management are generated at an interdisciplinary meeting. Each patient also receives education consisting of written materials about falls prevention, physical activity, and home safety. Bone fragility fracture risk assessment was performed using the World Health Organization’s Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX®) in Australia but not in Colombia. High-risk status identification assessment for falling was similar in both programs. If additional interventions were needed, referral to other services was recommended. The postintervention follow-up procedures were similar in both countries with the same interdisciplinary team reassessing the clients.

Figure 1 Comparative flow diagram for processing falls and fracture clinics in Australia and Colombia.

Abbreviations: 3D, three-dimensional; ADL, activities of daily living; ALCOVE, Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders; AUS, Australia; BMI, body mass index; COL, Colombia; FES-I, Falls Efficacy Scale-International; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; GPs, general practitioners; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MNA, Mini Nutritional Assessment; POMA, performance oriented mobility assessment; SPPB, short physical performance battery.

Discussion

This exploratory comparative analysis of two clinics in Australia and Colombia has revealed several similarities as well as differences. The clinics in both countries have major similarities in terms of organization and administration. Both programs serve older people who are very similar in terms of age, gender, and geography (mountainous areas). In addition, the multifactorial assessment and intervention model utilized in both countries closely follows previously recommended models for falls clinics.Citation2,Citation3 For identification of high-risk status for falls, both programs use the indicators developed by the ACOVE program.Citation23

The similarity of these findings suggests that both models could become a convergent solution to the problems associated with falling in an aging population. Falls are relatively common in both countries with similar prevalence: 28%–39% of people aged over 65 years experiencing at least one fall annually and up to 50% experiencing multiple falls.Citation24,Citation25 Overall, falls clinics have demonstrated a substantial reduction (35%–77%) in falls in high-risk populations and improvements in other outcomes such as balance and mobility, physical functioning, and fear of falling.Citation3 Therefore, these clinics represent an approach that provides specialized services for this common geriatric syndrome in developed and in developing countries.Citation6,Citation9,Citation10,Citation15,Citation18

Besides the overall similarities, there were1 several differences between the Australian and Colombian models. The first source of difference was the type of patients seen at each site in terms of race (mostly Caucasian in Australia and mostly Mestizo population in Colombia), nutritional status (higher body mass index in Australia), and level of education (secondary degree in most of the Australian population and in just half of the Colombian population).Citation27 Another difference was the criteria for eligibility with falling associated or not with a fragility fracture being the priority in Australia while falling associated with dizziness being the main focus in Colombia. This could be explained by higher access for orthopedic/ geriatric wards in Australia as well as the role of the recently implemented orthogeriatric model of care.Citation26 On the other hand, the prevalence of dizziness in Colombia was reported to be 15.2% in the older population and associated with more prevalent chronic conditions and physical and sensory impairments.Citation27 Therefore, the falls clinic in the Colombian program was established in conjoint with an otolaryngology service as interdisciplinary care to solve problems of older people with falls associated with dizziness.Citation18

The second difference was the most common type of intervention prescribed at each clinic. Although the multi-component program was similar in both countries, the most common type of intervention differed. Although Australia has sunny weather for most of the year, it still cannot boast a vitamin D-safe population.Citation28 Reasons for this are that lifestyles for many older people, particularly women, are increasingly associated with indoor activities and with foods not being fortified for vitamin D in Australia. Taken together, there is a high prevalence of vitamin deficiency in this particular Western Sydney population (45%),Citation29 thus a high level of vitamin D supplementation is required in this population. In Colombia, the falls clinic prioritized gentle balance exercise interventions at home due to the fact that despite 98% of Colombian older adults know about the benefits of exercise only 5% exercise every day.Citation30 Nevertheless, despite each clinic prioritizes a particular intervention for their target population, the whole comprehensive approach used at both settings is similar () and includes balance exercise, patient education, nutritional supplements, medication review, hearing and vision correction, and home modification. Overall, these evidence-based multifactorial interventionsCitation31 should constitute the key elements of any secondary prevention program for falls in older persons.

In terms of integrating the fracture prevention component, at the Australian clinic, fragility fracture risk is evaluated by clear identification of risk factors for fractures, quantification of absolute risk of fracture using FRAX (a fracture risk assessment tool that is not widely used in Colombia), and by bone mineral density measurement. Fracture risk assessment is followed by fracture prevention interventions such as osteoporosis treatment, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, and identification and treatment of secondary causes of bone loss.

Taken together, both programs are using a similar approach to two very prevalent problems in older people. However, components of the suggested models of NICECitation22 and ACOVECitation23 that are considered the optimal practice for falls and fractures prevention are at different degrees of implementation in both countries. Nevertheless, a common evaluation of the processes at both clinics allows a comprehensive revision of the processes and assessment tools and could constitute an initial step to developing an integrated model of secondary prevention of falls and fractures that could be implemented in both developed and developing countries worldwide. Based on this comparison, the authors propose that falls clinic services should be operationally linked to osteoporosis services as a “falls and fracture prevention clinic,” which would facilitate a comprehensive intervention to prevent falls and fractures in older persons. Finally, more intensive studies are needed to gain a better understanding of how falls and fractures clinics operate and to identify more precisely their benefits and limitations. Finally, further evaluation with a randomized controlled trial is required to confirm the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of this model of care.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an Australian Leadership Award Fellowship (ALAF) from Australian Government Overseas Aid Program (AusAID) to Dr Gomez and a grant from the Nepean Medical Research Foundation to Professor Duque. The authors would like to thank the support from the University of Caldas (Manizales, Colombia).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HoughtonSBirksVWhiteheadCHCrottyMExperience of a falls and injuries risk assessment clinicAust Health Rev200428337438115595921

- HillKSmithRSchwarzJFalls clinics in Australia: a survey of current practice, and recommendations for future developmentAust Health Rev200124416317411842706

- HillKDMooreKJDorevitchMIDayLMEffectiveness of falls clinics: an evaluation of outcomes and client adherence to recommended interventionsJ Am Geriatr Soc200856460060818266663

- ThomasSMillerMWhiteheadCCrottyMFalls clinics: an opportunity to address frailty and improve health outcomes (preliminary evidence)Aging Clin Exp Res201022217017420440103

- Wolf-KleinGPSilverstoneFABasavarajuNFoleyCJPascaruAMaPHPrevention of falls in the elderly populationArch Phys Med Rehabil19886996896913421823

- Hart-HughesSQuigleyPBulatTPalaciousPScottSAn interdisciplinary approach to reducing fall risks and fallsJ Rehabil2004704651

- PerellKLManzanoMLWeaverROutcomes of a consult fall prevention screening clinicAm J Phys Med Rehabil2006851188288817079960

- MooreMWilliamsBRagsdaleSTranslating a multifactorial fall prevention intervention into practice: a controlled evaluation of a fall prevention clinicJ Am Geriatr Soc201058235736320370859

- HuskJJensenJO’RiordanSThe local falls and osteoporosis service: does it meet the needs of patients?Nurs Older People20071910343818220068

- PuisieuxFPollezBDeplanqueDSuccesses and setbacks of the falls consultation: report on the first 150 patientsAm J Phys Med Rehabil2001801290991511821673

- EvronLSchultz-LarsenKEgerodIEstablishing a new falls clinic– conflicting attitudes and inter-sectoral competition affecting the outcomeScand J Caring Sci200923347348119077063

- Lazaro del NogalMGonzalez-RamirezAPalomo-IloroAEvaluacion del riesgo de caídas. Protocolos de valoración clínica. [Evaluating the risk of falls. Clinical evaluation protocols]Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol200540(Suppl 2)5463 Spanish

- SzePCCheungWHLamPSLoHSLeungKSChanTThe efficacy of a multidisciplinary falls prevention clinic with an extended step-down community programArch Phys Med Rehabil20088971329133418586135

- Providence Health CareOutpatient services: falls and fracture prevention clinic2008 Available from http://www.providencehealthcare.org/info_outpatient_ff_prevention.htmlAccessed September 26, 2012

- BauerCGrogerIGlabasniaABerglerCGassmannKGFirst results of evaluation of a falls clinicInt J Gerontol201043130136

- SchoonYHoogsteen-OssewaardeMESchefferACVan RooijFJRikkertMGDe RooijSEComparison of different strategies of referral to a fall clinic: how to achieve an optimal casemix?J Nutr Health Aging201115214014521365168

- SimoceliLBittarRSMBottinoMABentoRFPerfil diagnóstico do idoso portador de desequilíbrio corporal: resultados preliminaries [Diagnostic approach of balance in the elderly: preliminary results]Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol2003696772777 Portuguese

- AltamarGCurcioCLRossoVOsorioJLGomezFEvaluación del mareo en ancianos en una clínica de inestabilidad, vértigo y caídas [Assessment of dizziness in the elderly population in a special clinic for the treatment of lack of stability, vertigo, and falls]Acta Med Colomb2008331210 Spanish

- FederGCryerCDonovanSCarterYGuidelines for the prevention of falls in people over 65BMJ200032172671007101111039974

- CloseJCMcMurdoMEBritish Geriatrics SocietyFalls and bone health services for older peopleAge Ageing200332549449612957997

- National Institute for Health and Clinical ExcellenceClinical Guideline 21: Falls. The Assessment and Prevention of Falls in Older PeopleLondonNational Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence2004 Available from http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/10956/29583/29583.pdfAccessed December 10, 2012

- LambSEJorstad-SteinECHauerKBeckerCDevelopment of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensusJ Am Geriatr Soc20055391618162216137297

- ChangJTGanzDAQuality indicators for falls and mobility problems in vulnerable eldersJ Am Geriatr Soc200755(Suppl 2)S32733417910554

- LordSRSherringtonCMenzHBCloseJCTFalls in Older People: Risk Factors and Strategies for Prevention2nd edCambridgeCambridge University Press2007

- CurcioCLGomezJFGarcíaAFalls and functional capacity amongst sedentary and exercise-performing Colombian elderlyColomb Med1998294125128 Spanish

- ACI: NSW Agency for Clinical InnovationThe orthogeriatric model of care Available from http://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_fle/0013/153400/aci_orthogeriatrics_clinical_practice_guide.pdf#zoom=100Accessed October 5, 2012

- GomezFCurcioCLDuqueGDizziness as a geriatric condition among rural community-dwelling older adultsJ Nutr Health Aging201115649049721623472

- ClemsonLFinchCFHillKDLewinGFall prevention in Australia: policies and activitiesClin Geriatr Med201026473374920934619

- BoersmaDDemontieroOMohtashamAmiri ZVitamin D status in relation to postural stability in the elderlyJ Nutr Health Aging201216327027522456785

- Ministry of HealthNational Study on Risk Factors and Chronic Disease (ENFREC II). Technical Document seriesBogotaMinistry of Health1999 Spanish

- MichaelYLWhitlockEPLinJSFuRO’ConnorEAGoldRPrimary care-relevant interventions to prevent falling in older adults: a systematic evidence review for the US. Preventive Services Task ForceAnn Intern Med20101531281582521173416