Abstract

Purpose

Treatment intensity for elderly patients with end-stage renal disease has escalated beyond population growth. Ageism seems to have given way to a powerful imperative to treat patients irrespective of age, prognosis, or functional status. Hemodialysis (HD) is a prime example of this trend. Recent articles have questioned this practice. This paper aims to identify existing pre-synthesized evidence on HD in the very elderly and frame it from the perspective of a clinician who needs to involve their patient in a treatment decision.

Patients and methods

A comprehensive search of several databases from January 2002 to August 2012 was conducted for systematic reviews of clinical and economic outcomes of HD in the elderly. We also contacted experts to identify additional references. We applied the rigorous framework of decisional factors of the Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) to evaluate the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.

Results

We found nine eligible systematic reviews. The quality of the evidence to support the current recommendation of HD initiation for most very elderly patients is very low. There is significant uncertainty in the balance of benefits and risks, patient preference, and whether default HD in this patient population is a wise use of resources.

Conclusion

Following the GRADE framework, recommendation for HD in this population would be weak. This means it should not be considered standard of care and should only be started based on the well-informed patient’s values and preferences. More studies are needed to delineate the true treatment effect and to guide future practice and policy.

Introduction

Over the past two decades treatment intensity for elderly patients with terminal conditions has escalated beyond population growth.Citation1–Citation3 Ageism, characteristic of the early days of Hemodialysis (HD),Citation4 seems to have given way to a powerful imperative to treat patients irrespective of age, prognosis, or functional status.Citation5 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is a prime example of this trend with a 57% age-adjusted increase in HD for octo- and nonagenarians between 1996 and 2003,Citation1 partly due to a push for earlier initiation of HD, especially in patients over 75.Citation6 This has happened despite an Institute of Medicine report in 1991 calling attention to an increasing number of dialysis patients with poor quality of life (QoL) and limited survival possibilitiesCitation7, and subsequent treatment guidelines in 2000 emphasizing shared decision making and outlining when HD treatment may be considered of minimal benefit.Citation8 Patients report not being given enough information to make informed decisions and to be given a choice of dialysis or nothing.Citation5,Citation9

Although the benefits of HD in aggregate are undeniable, benefits to certain high-risk subgroups are uncertain,Citation10,Citation11 and the quality of evidence available to guide practice and policy is questionable, particularly in the very elderly. Meanwhile, the evidence of significant harm for certain subpopulations is mounting.Citation11–Citation13 Moreover, more than half of ESRD patients on dialysis experience significant symptoms, such as pain, fatigue, pruritus, nausea, and constipation.Citation14 Data are quite limited on symptom prevalence in ESRD patients managed conservatively without dialysis.Citation14

To develop evidence-based recommendations regarding HD in the very elderly (≥75 years old), several factors should be considered including the quality of evidence supporting benefit and harm, patients’ values, preferences, and clinical and social context, as well as resource availability. In this paper, we incorporate these decisional factors following the rigorous framework of the Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation, (GRADE) framework.Citation15 To our knowledge, this is the first description of applying this framework, which is increasingly becoming the state-of-the-art guideline development process, to this important clinical question.

Methods

This study follows an umbrella systematic review designCitation16 and aims to identify existing pre-synthesized evidence in published systematic reviews, as well as to frame them from the perspective of a clinician who needs to make a single treatment decision.

Data sources and search strategies

A comprehensive search of several databases from January 2002 to August 2012, in any language, was conducted. The databases included Ovid Medline In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus. The search strategy was designed and conducted by an experienced librarian with input from the study’s principal investigator. Controlled vocabulary, supplemented with keywords, was used to search for systematic reviews of outcomes and economics of HD in the elderly. Reference lists were hand searched and expert colleagues were approached for relevant articles. We then applied A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) grading systemCitation17 to the systematic reviews to assess their quality (Supplementary material).

Rating the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations

We applied the GRADE framework to the available research evidence. The quality of evidence depends on the elements of risk of bias, imprecision, indirectness, reporting and publication bias and inconsistency. The strength of recommendations depends on the quality of evidence, patients’ values and preferences, balance between harms and benefits and resource utilization. The recommendations can be strong (apply to most patients in most settings) or weak (conditional, can vary based on patients context, resources and preferences).Citation15

Results

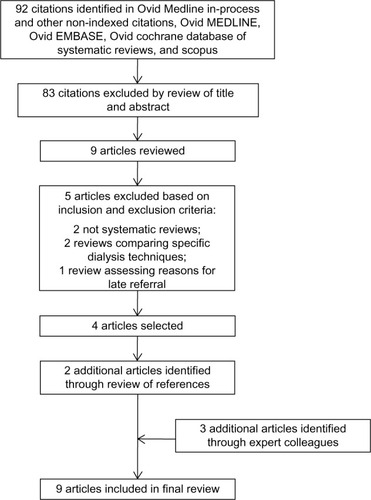

The search strategy yielded 92 articles, and reference review and expert contact yielded five additional articles. Lastly, we included nine systematic reviews that provided data on the outcomes of interest and are included in this review ().Citation9,Citation14,Citation18–Citation24

The methodological quality of these systematic reviews was moderate to high, satisfying most of the AMSTAR quality indicators (). The included systematic reviews were particularly deficient in the areas of restricting their search to the English language and their inability to evaluate for publication bias ( and ).

Table 1 Quality of systematic review (AMSTAR quality indicators)

Quality of evidence for benefit

Based on the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), the expected remaining lifetime for patients 75–79 years old with ESRD undergoing HD is 2.8 years, 2.3 years for 80- to 84-year-old patients, and 1.9 years for the age group ≥ 85 years old.Citation25 No comparable national registry or large cohort data is available for patients who opt for conservative treatment. Smaller cohort studies were recently summarized in a systematic review of conservatively managed ESRD patients that demonstrated a median survival of at least 6 months with a range of 6.3–23.4 months.Citation18 Five prognostic studies compared patients on HD with supportive care. All of them reported statistically significant survival benefits, but the groups were poorly balanced on either age,Citation26–Citation28 other prognostic factors,Citation27,Citation29 or both,Citation27,Citation30 and there was significant heterogeneity in their population and methods. One of the studies looked specifically at the survival of a small subgroup of patients for whom palliative care had been recommended and showed no significant survival benefit.Citation27 Another study looked at median survival from the first known date of glomerular filtration rate < 15 and found minimal survival benefit with HD.Citation28 The studies were all cohort studies; three of which were prospectiveCitation26,Citation27,Citation29 and two were retrospective.Citation28,Citation30 Three of the studies specifically evaluated the older patients (over age 70 or 75),Citation26,Citation28,Citation30 and even in those studies the groups were poorly balanced in terms of age.

In addition, elderly patients who suffer acute kidney injury are less likely to recover kidney function and become independent from dialysis therapyCitation19 and are more likely to suffer fistula failure than younger patients.Citation21

Thus, the overall quality of evidence supporting a modest survival benefit with HD in the elderly is considered to be very low (due to the methodological limitations of the studies and heterogeneity).

Quality of evidence for harm

In recent studies there is mounting evidence of a risk of harm from HD in the very elderly.Citation11 A large retrospective registry cohort study of 3702 nursing-home patients was conducted using functional status from the Minimal Data Set Activities of Daily Living (MDS-ADL) score from 3 months prior, to until 12 months after the onset of HD. There was no comparison group of conservatively treated patients. The study demonstrated a rapid decline in functional status and high mortality. Only 13% maintained functional status at 12 months, and the 1-year mortality rate was 58%.Citation12 A small (n = 97) single-center retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data on living status showed that the proportion of independently living elderly patients rapidly declined from 78% at baseline to 23% at 1 year, 11% at 2 years, and 4% at the end of follow-up.Citation13 Similarly, there was no comparison group in this study.

Qualitative studies report significant patient suffering.Citation31 Symptom burden for patients with ESRD is consistently reported as very high for patients on HD,Citation14 with limited comparative data for patients on supportive care only.Citation14 Contrary to common belief, HD does not always improve symptom control, and symptom burden is higher at 6 months than at HD initiation.Citation32 Withdrawal rates in the oldest USRDS population range from 25%–34%.Citation33 Palliative and hospice care is underutilized even for those patients who decide to discontinue HD.Citation34 Symptoms are often undertreatedCitation35 despite available and effective treatments.Citation36,Citation37

Once on HD, aggressive end-of-life care is pervasive and more aggressive than for patients with other chronic life-limiting illnesses as demonstrated by a retrospective cohort study of over 99,000 USRDS decedents.Citation38 Patients on HD spend significantly more days in the hospital and in the HD unit and are much less likely to die at home than patients receiving supportive care (odds ratio for home death on supportive care is 4.15; 95% CI 1.67–10.25).Citation26 Patients may spend the majority of any extra days survived in the hospital or HD unit.Citation26 These data are based on a prospective cohort study of 202 patients over 70 years of age. Two other prospective studies of 321 and 71 patients, respectively, have shown similar findings for site of death.Citation27,Citation39

In summary, the quality of evidence suggesting harms associated with HD in the elderly is also low as it is mostly based on observational studies lacking comparison groups, except for the risk for institutional death which is based on prospective cohort data.

Uncertainty or variability in values and preferences

In a situation in which the balance of benefits and risks are uncertain, eliciting the values and preferences of patients and empowering them and their surrogates to make decisions consistent with their goals of care becomes even more important. Defining the benefit of treatment should be in the patients’ purview.Citation40

Qualitative studies and surveys suggest that most patients on HD do not perceive that they have been given a choice of treatmentCitation41,Citation42 and many regret having started HD.Citation32,Citation42 Receipt of intensive end-of-life care in HD patients also seems to be driven more by practice related factors than patient characteristics.Citation38 Six prominent patient goals of care have been identified in a structured literature reviewCitation43 and validated in subsequent studies.Citation44 Patients can have multiple goals of care. While 84% of hospitalized patients endorsed living longer as one of their goals, it was the single most important goal for less than 10% of patients.Citation44 A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies on the views of chronic kidney disease patients regarding treatment decision making also reached the conclusion that patients were more concerned about the impact on QoL than longevity.Citation9 Despite this, none of the studies comparing survival between groups looked at QoL data or loss of functional status.Citation26–Citation30 Only two studies directly comparing QoL were identified by the systematic review on conservative management of ESRD.Citation18 Yong et al reported better QoL in the conservatively managed group despite the fact that the patients were older and had higher comorbidity.Citation45 De Biase et al compared two groups of patients who were recommended for palliative care and found that those who opted for HD had a similar QoL compared to those who opted for supportive care.Citation46

There is significant variability in elderly patient’s values and preferences when facing decisions regarding treatment options for ESRD. The available evidence suggests a failure to honor those differences by failing to involve elderly patients in shared decision making before starting HD.

Uncertainty about whether the intervention represents a wise use of resources

There is increasing concern about the cost of care for the growing elderly population in the context of a looming bankruptcy of Medicare.Citation47 Currently, Medicare spends over a quarter of its budget on the 5%–6% of its beneficiaries that die each year.Citation48 High costs associated with the last months of life and terminal hospitalizations/ICU stays have been cited as an area of potential savings with minimal harm or even benefit.Citation49 In addition, there is concern about the increasing medicalization of death and “bad hospital deaths” with significant patient suffering and financial and emotional burdens on loved ones left behind.Citation50–Citation52 The HD benefit is a significant portion of the Medicare budget consuming approximately 6% of the entire budget for a disease with a prevalence of 1,780 per million, representing 1% of the total Medicare population.Citation33

The cost effectiveness of HD has been cited as a benchmark for societal willingness to pay for medical treatment.Citation22 A meta-analytic review of the cost effectiveness of HD found the estimate to remain within a narrow range of $55,000 to $80,000 per life-year saved.Citation22 However, the costs and cost effectiveness ratios in this analysis may have been underestimated since informal caregiver time was not included in most of the studies. Another weakness identified in all studies was the assumption of no life expectancy for patients who were not dialyzed, which does not hold, especially in the setting of early initiation of HD. The true cost based on USRDS data for the oldest HD patients, with congestive heart failure and diabetes mellitus as comorbidities, is at or above $100,000 in 2006 US dollars.Citation25,Citation53 Given the questionable survival benefit of HD outlined above, the dollars per quality-adjusted life-year saved are likely much higher. A recent empirical estimate to update the HD cost effectiveness standard arrived at an average of $129,000 per Quality Added Life Years (QALY) with a wide distribution.Citation54 The patients in the highest quintile (mostly older and sicker) had costs of about $250,000/QALY. Another study showed a cost effectiveness ratio of $250,000 for early initiation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 15 compared to current practice.Citation55 Peritoneal dialysis is more cost effective than HDCitation24,Citation56 and is currently underutilized in the US.Citation57

There is significant uncertainty in the cost effectiveness estimates for the oldest HD patients secondary to the uncertainty about the true treatment benefit. Hemodialysis in the frail elderly and others with multiple comorbidities is very costly and, depending on the societal benchmark for willingness to pay, may not constitute a wise use of resources.

Research gaps

This analysis of the existing evidence suggests that there is sufficient equipoise regarding the benefits of HD for the oldest patients to warrant a randomized controlled trial of HD vs best supportive care. Better evidence is needed to enable sound policy decisions that preserve access to HD yet minimize the risk of overutilization and possible harm to patients who are likely to benefit only marginally or suffer harms from this expensive treatment.

Ideally, the recruitment for the study would utilize well-developed patient decision aids to convey the available evidence on patient survival as well as the uncertainty of the estimate. Peer educators would also be valuable to provide the experiential aspect of dialysis care.Citation58 Patients should be risk stratified using one of the available tools for ESRD patients.Citation59 In the analysis, correcting for the GFR at the start of HD should also be used to correct for lead time bias with the current early initiation of HD.

The study would need to consider all patient important outcomes including survival from diagnosis, frequency of hospitalizations and number of hospital and ICU days, QoL and symptom burden (measured with validated tools such as the Kidney Disease Quality Of Life 36Citation60 or Short Form12Citation61), and finally the proportion of hospital vs home deaths. Calculating the cost of care for both treatment arms would also be important for comparative effectiveness purposes.

We realize that there might be significant barriers to recruitment into such a study given the powerful technical and moral imperative to treatCitation5, as well as the risk of being accused of advocating death panels or of being ageist.Citation62,Citation63 Patients may also be resistant to randomization based on their goals of care. If this proves to be the case, we suggest the creation of a large-scale cohort of elderly patients with ESRD who opt for conservative management to create a valid comparison group to the USRDS database on HD patients.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that the quality of the evidence to support the current practice of HD initiation for most very elderly patients is very low. Survival benefit is questionable and modest at best, and there are significant concerns for harm such as decline in functional status, high treatment and symptom burden, poor QoL, aggressive end-of-life care, and institutionalized death. Moreover, this is a costly treatment. More studies are needed to delineate the true treatment effect and to guide future practice and policy.

Following the GRADE framework, recommendation for HD in this population would be weak, which means it should not be considered default treatment in the majority of cases and should only be offered based on the well-informed patient’s values and preferences.

The recent push for early HD initiation in this age group is not justified. The suggestion of a risk of harm, coupled with a failure of early initiation to demonstrate improved survival,Citation64,Citation65 would support holding off from HD as long as clinically possible. A significant number of patients are likely to die of other causes before they reach the point of inevitable HD.Citation66

Patients’ goals of care should be the guiding light in all treatment decisions and physicians should not feel obliged to dialyze everyone. In fact the Hippocratic maxim “first do no harm” should be weighed against the moral imperative to treat.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

We thank Gladys Hebl from Mayo Clinic Grant and Publication Support Services for her help in preparing this manuscript for publication.

Supplementary material

Search strategies by database.

Ovid

Database(s): Embase 1988 to 2012 Week 33, Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present, EBM Reviews – Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005 to July 2012.

Search strategy:

Scopus

TITLE-ABS-KEY((renal W/5 dialyses) or (kidney w/5 dialyses) or (blood w/5 dialyses) or (peritoneal w/5 dialyses) or (renal W/5 dialysis) or (kidney w/5 dialysis) or (blood w/5 dialysis) or (peritoneal w/5 dialysis) or hemodialysis or haemodialysis or hemodialyses or haemodialyses or “extracorporeal dialysis” or “extracorporeal dialyses” or “extracorporeal blood cleansing” or hemodialyse or hemorenodialysis or hemorenodialyses or hemotrialysate or Hemodiafiltration) AND PUBYEAR > 2001

TITLE-ABS-KEY(elderly or octagenarian* or nonagenarian* or “very old” or “75 year*” or “80 year*” or “90 year*” or “100 year*” or (75 w/1 age) or (80 w/1 age) or (90 w/1 age) or (100 w/1 age) or (75 w/1 aged) or (80 w/1 aged) or (90 w/1 aged) or (100 w/1 aged))

TITLE-ABS-KEY(outcome* or economic* or cost or costs or benefit* or harm* or preference* or “quality of life” or survival or “functional status” or morbidity or mortality or satisfaction)

and 2 and 3

PMID(0*) OR PMID(1*) OR PMID(2*) OR PMID(3*) OR PMID(4*) OR PMID(5*) OR PMID(6*) OR PMID(7*) OR PMID(8*) OR PMID(9*)

and not 6

DOCTYPE(le) OR DOCTYPE(ed) OR DOCTYPE(bk) OR DOCTYPE(er) OR DOCTYPE(no) OR DOCTYPE(sh)

and not 7

TITLE-ABS-KEY(systematic* w/3 review*)

and 9

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KurellaMCovinskyKECollinsAJChertowGMOctogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United StatesAnn Intern Med2007146317718317283348

- SharmaGFreemanJZhangDGoodwinJSTrends in end-of-life ICU use among older adults with advanced lung cancerChest20081331727817989164

- EarleCCLandrumMBSouzaJMNevilleBAWeeksJCAyanianJZAggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue?J Clin Oncol200826233860386618688053

- KjellstrandCAll elderly patients should be offered dialysisGeriatr Nephrol Urol19976129136

- KaufmanSRShimJKRussAJRevisiting the biomedicalization of aging: clinical trends and ethical challengesGerontologist200444673173815611209

- O’HareAMChoiAIBoscardinWJTrends in timing of initiation of chronic dialysis in the United StatesArch Intern Med2011171181663166921987197

- Institute of Medicine, Division of Health Care Services, Committee for the Study of the Medicare End-Stage Renal Disease ProgramKidney Failure and the Federal GovernmentWashington, DCNational Academy Press1991

- Renal Physicians AssociationShared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis. Clinical Practice GuidelineRockville, MDRenal Physicians Association2010

- MortonRLTongAHowardKSnellingPWebsterACThe views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studiesBMJ2010340c11220085970

- ThorsteinsdottirBSwetzKMFeelyMAMuellerPSWilliamsAWAre there alternatives to hemodialysis for the elderly patient with end-stage renal failure?Mayo Clin Proc201287651451622677071

- RosanskySJThe sad truth about early initiation of dialysis in elderly patientsJAMA2012307181919192022570459

- Kurella TamuraMCovinskyKEChertowGMYaffeKLandefeldCSMcCullochCEFunctional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysisN Engl J Med2009361161539154719828531

- JassalSVChiuEHladunewichMLoss of independence in patients starting dialysis at 80 years of age or olderN Engl J Med2009361161612161319828543

- MurtaghFEMAddington-HallJHigginsonIJThe prevalence of symptoms in end-stage renal disease: a systematic reviewAdv Chronic Kidney Dis2007141829917200048

- AtkinsDBestDBrissPAGrading quality of evidence and strength of recommendationsBMJ20043287454149015205295

- ThomsonDRussellKBeckerLKlassenTHartlingLThe evolution of a new publication type: Steps and challenges of producing overviews of reviewsRes Synth Method201013–4198211

- SheaBJHamelCWellsGAAMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviewsJ Clin Epidemiol200962101013102019230606

- O’ConnorNRKumarPConservative management of end-stage renal disease without dialysis: a systematic reviewJ Palliat Med201215222823522313460

- SchmittRCocaSKanbayMTinettiMECantleyLGParikhCRRecovery of kidney function after acute kidney injury in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Kidney Dis200852226227118511164

- JohnsonRFGustinJAcute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy in the intensive care unit: impact on prognostic assessment for shared decision makingJ Palliat Med201114788388921612503

- LazaridesMKGeorgiadisGSAntoniouGAStaramosDNA meta-analysis of dialysis access outcome in elderly patientsJ Vasc Surg200745242042617264030

- WinkelmayerWCWeinsteinMCMittlemanMAGlynnRJPliskinJSHealth economic evaluations: the special case of end-stage renal disease treatmentMed Decis Making200222541743012365484

- MenzinJLinesLMWeinerDEA review of the costs and cost effectiveness of interventions in chronic kidney disease: implications for policyPharmacoeconomics2011291083986121671688

- MowattGValeLPerezJSystematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and economic evaluation, of home versus hospital or satellite unit haemodialysis for people with end-stage renal failureHealth Technol Assess200372117412773260

- US Renal Data SystemUSRDS 2008 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United StatesBethesda, MDNational Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases2008

- CarsonRCJuszczakMDavenportABurnsAIs maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease?Clin J Am Soc Nephrol20094101611161919808244

- SmithCDa Silva-GaneMChandnaSWarwickerPGreenwoodRFarringtonKChoosing not to dialyse: evaluation of planned non-dialytic management in a cohort of patients with end-stage renal failureNephron Clin Pract2003952c40c4614610329

- MurtaghFEMarshJEDonohoePEkbalNJSheerinNSHarrisFEDialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5Nephrol Dial Transplant20072271955196217412702

- JolyDAnglicheauDAlbertiCOctogenarians reaching end-stage renal disease: cohort study of decision-making and clinical outcomesJ Am Soc Nephrol20031441012102112660336

- ChandnaSMDa Silva-GaneMMarshallCWarwickerPGreenwoodRNFarringtonKSurvival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapyNephrol Dial Transplant20112651608161421098012

- RussAJShimJKKaufmanSR“Is there life on dialysis?”: time and aging in a clinically sustained existenceMed Anthropol200524429732416249136

- StringerSBaharaniJWhy did I start dialysis? A qualitative study on views and expectations from an elderly cohort of patients with end-stage renal failure starting haemodialysis in the United KingdomInt Urol Nephrol201244129530021850412

- US Renal Data SystemUSRDS 2011 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United StatesBethesda, MDNational Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases2011

- MurrayAMArkoCChenSCGilbertsonDTMossAHUse of hospice in the United States dialysis populationClin J Am Soc Nephrol2006161248125517699355

- ClaxtonRNBlackhallLWeisbordSDHolleyJLUndertreatment of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysisJ Pain Symptom Manage201039221121819963337

- CohenLMMossAHWeisbordSDGermainMJRenal palliative careJ Palliat Med20069497799216910813

- BarakzoyASMossAHEfficacy of the world health organization analgesic ladder to treat pain in end-stage renal diseaseJ Am Soc Nephrol200617113198320316988057

- WongSPKreuterWO’HareAMTreatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysisArch Intern Med20121728:661663 discussion 663–66422529233

- WongCFMcCarthyMHowseMLWilliamsPSFactors affecting survival in advanced chronic kidney disease patients who choose not to receive dialysisRen Fail200729665365917763158

- PellegrinoEDDecisions to withdraw life-sustaining treatment: a moral algorithmJAMA200028381065106710697071

- RussAJKaufmanSRDiscernment rather than decision-making among elderly dialysis patientsSemin Dial2012251313222273528

- DavisonSNEnd-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney diseaseClin J Am Soc Nephrol20105219520420089488

- KaldjianLCCurtisAEShinkunasLACannonKTGoals of care toward the end of life: a structured literature reviewAm J Hosp Palliat Care200825650151119106284

- KaldjianLCEreksonZDHaberleTHCode status discussions and goals of care among hospitalised adultsJ Med Ethics200935633834219482974

- YongDSKwokAOWongDMSuenMHChenWTTseDMSymptom burden and quality of life in end-stage renal disease: a study of 179 patients on dialysis and palliative carePalliat Med200923211111919153131

- De BiaseVTobaldiniOBoarettiCProlonged conservative treatment for frail elderly patients with end-stage renal disease: the Verona experienceNephrol Dial Transplant20082341313131718029376

- RoyATrustees: Medicare Will Go Broke in 2016, If You Exclude Obamacare’s Double-Counting. Forbes [serial on the Internet]4232012 Available from: http://www.forbes.com/sites/aroy/2012/04/23/trustees-medicare-will-go-broke-in-2016-if-you-exclude-obamacares-double-counting/Accessed May 8, 2013

- RileyGFLubitzJDLong-term trends in Medicare payments in the last year of lifeHealth Serv Res201045256557620148984

- ZilberbergMDShorrAFEconomics at the end of life: hospital and ICU perspectivesSemin Respir Crit Care Med201233436236922875382

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on Care at the End of LifeApproaching Death: Improving Care at the End of LifeWashington, DCThe National Academies Press1997

- HimmelsteinDUThorneDWarrenEWoolhandlerSMedical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: results of a national studyAm J Med2009122874174619501347

- WendlerDRidASystematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for othersAnn Intern Med2011154533634621357911

- KnaufFAronsonPSESRD as a window into America’s cost crisis in health careJ Am Soc Nephrol200920102093209719729435

- LeeCPChertowGMZeniosSAAn empiric estimate of the value of life: updating the renal dialysis cost-effectiveness standardValue Health2009121808719911442

- LeeCPChertowGMZeniosSAA simulation model to estimate the cost and effectiveness of alternative dialysis initiation strategiesMed Decis Making200626553554916997929

- TeerawattananonYMugfordMTangcharoensathienVEconomic evaluation of palliative management versus peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis for end-stage renal disease: evidence for coverage decisions in ThailandValue Health2007101617217261117

- MitkaMDeveloped countries lag in use of cheaper and easier peritoneal dialysisJAMA2012307222360236122692152

- PerryESwartzJBrownSSmithDKellyGSwartzRPeer mentoring: a culturally sensitive approach to end-of-life planning for long-term dialysis patientsAm J Kidney Dis200546111111915983964

- CouchoudCDialysis: Can we predict death in patients on dialysis?Nat Rev Nephrol20106738838920585316

- HaysRDKallichJDMapesDLCoonsSJCarterWBDevelopment of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) instrumentQual Life Res1994353293387841967

- WareJKosinskiMKellerSDA 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validityMed Care19963432202338628042

- VierraMDeath PanelsAnn Intern Med2012156539439522393137

- KettlPA piece of my mind. One vote for death panelsJAMA2010303131234123520371773

- CooperBABranleyPBulfoneLA randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysisN Engl J Med2010363760961920581422

- WinkelmayerWCLiuJChertowGMTamuraMKPredialysis nephrology care of older patients approaching end-stage renal diseaseArch Intern Med2011171151371137821824952

- KeithDSNicholsGAGullionCMBrownJBSmithDHLongitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organizationArch Intern Med2004164665966315037495