Abstract

Objective

Delirium is associated with poor outcomes following acute hospitalization. A specialized delirium management unit, the Geriatric Monitoring Unit (GMU), was established. Evening bright light therapy (2000–3000 lux; 6–10 pm daily) was added as adjunctive treatment, to consolidate circadian activity rhythms and improve sleep. This study examined whether the GMU program improved sleep, cognitive, and functional outcomes in delirious patients.

Method

A total of 228 patients (mean age = 84.2 years) were studied. The clinical characteristics, delirium duration, delirium subtype, Delirium Rating Score (DRS), cognitive status (Chinese Mini–Mental State Examination), functional status (modified Barthel Index [MBI]), and chemical restraint use during the initial and predischarge phase of the patient’s GMU admission were obtained. Nurses completed hourly 24-hour patient sleep logs, and from these, the mean total sleep time, number of awakenings, and sleep bouts (SB) were computed.

Results

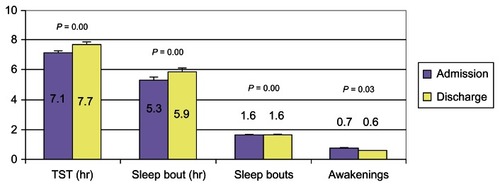

The mean delirium duration was 6.7 ± 4.6 days. Analysis of the delirium subtypes showed that 18.4% had hypoactive delirium, 30.2% mixed delirium, and 51.3% had hyperactive delirium. There were significant improvements in MBI scores, especially for the hyperactive and mixed delirium subtypes (P < 0.05). Significant improvements were noted on the DRS sleep–wake disturbance subscore, for all delirium-subtypes. The mean total sleep time (7.7 from 6.4 hours) (P < 0.05) and length of first SB (6.0 compared with 5.3 hours) (P < 0.05) improved, with decreased mean number of SBs and awakenings. The sleep improvements were mainly seen in the hyperactive delirium subtype.

Conclusion

This study shows initial evidence for the clinical benefits (longer total sleep time, increased first SB length, and functional gains) of incorporating bright light therapy as part of a multicomponent delirium management program. The benefits appear to have occurred mainly in patients with hyperactive delirium, which merits further in-depth, randomized controlled studies.

Introduction

Delirium is a common and serious condition in older hospitalized patients. The prevalence in hospitalized elderly patients is as high as 50%, being present in 11%–24% of older patients at admission, with another 5%–35% developing delirium during admission.Citation1,Citation2 It is an indicator of severe underlying illness, necessitating early diagnosis and prompt treatment. Despite varying etiologies, delirium has a characteristic constellation of symptoms, suggesting a common neural pathway. Importantly, motor symptoms are core symptoms, associated with cognitive impairments and sleep disturbances.

The usually cited factors for delirium include advanced age, preexisting cognitive impairment, serious medical conditions, medications (such as benzodiazepines), environmental factors, and sleep deprivation. Attention and memory impairment have been observed after periods of total and partial sleep deprivation,Citation3,Citation4 suggesting a mechanistic relationship between delirium and sleep deprivation that may be mediated through involvement of the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems, although direct relationship between the two remains to be fully elucidated. Most of the available literature on delirium and sleep have involved intensive care unit patients. Critically ill patients, especially older adults, are known to experience poor sleep quality, with severe sleep fragmentation and sleep architecture disruption.Citation5,Citation6

Delirium is associated with an increased need for nursing surveillance, greater hospital costs, and high mortality rates of 25%–33% during hospitalization and 35%–40% at 1 year.Citation7–Citation12 In partial response to this, the Geriatric Monitoring Unit (GMU) was developed in October 2010 at the Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore, using an evidence-based approach incorporating specific interventions established to be beneficial for delirium care. The details of the GMU have been published previously.Citation13 To summarize, the GMU incorporated specific measures from the following programs: (1) Delirium Room, which provides comprehensive medical care, with multidisciplinary team meetings, and employs behavioral and appropriate nonpharmacological strategies as first-line management in delirious patients,Citation14 (2) the concept of structured core interventions from the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP),Citation15–Citation22 and (3) bright light therapy to establish a healthy sleep–wake cycle, with appropriate timing to effectively shift an altered circadian sleep–wake cycle to the desired phase.

Bright light therapy has gained increasing attention in recent years, as a potential environmental modifier (zeitgeber) of circadian rhythms. Additionally, therapeutic benefits have been demonstrated in terminally ill patients,Citation23 as well as those with seasonal affective disorders.Citation24 In elderly patients with advanced sleep phase syndrome, evening exposure to bright light daily has been demonstrated to be beneficial.Citation25–Citation31 This can be achieved using a bright light box of 1000–3000 lux or natural exposure to the sun for 1–2 hours daily in the late afternoon and early evening. The aim of bright light therapy is to establish healthy sleep–wake cycles. A recent study demonstrated the utility of light therapy in adjusting the rest–activity cycle and improving bed rest in postesophagectomy patients, with decreased occurrences of incident delirium.Citation32 Since sleep deprivation may aggravate delirium, it was anticipated that delirious patients would benefit from modulation of their sleep–wake cycle, while in the GMU. The peaceful environment of the GMU (without potential disruption by other patients) would facilitate uninterrupted sleep at night, while structured core interventions (with therapeutic activities) aimed to keep patients engaged in the day.

This study examined the impact of the GMU as a multicomponent intervention on outcomes of sleep, cognitive, and functional performance, in acute, hospitalized delirious older adults.

Methods

Subjects

We recruited 228 delirious patients who had been admitted to the GMU, Department of Geriatric Medicine, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore between December 2010 to August 2012. The subjects were classified into a hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed delirium subtype, based on their activity patterns. A patient was deemed to have recovered from delirium if the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)Citation33 criteria were no longer met, with the diagnosis of recovery being supported by improvement in cognitive and/or delirium severity scores, based on the Delirium Rating Score–R98 (DRS-R98) Citation34 and CAM-severity scores as well as input from the multidisciplinary team.

Inclusion/exclusion

The admission criteria for the GMU included patients above 65 years old who were admitted to the geriatric medicine department and assessed to have delirium (either on admission or incident delirium during hospital stay), established in accordance with the CAM. Patients were excluded if they had medical illnesses that required special monitoring (eg, telemetry for arrhythmias or acute myocardial infarction); were assessed to be dangerously ill, in a coma, or had a terminal illness; uncommunicative or diagnosed with severe aphasia; demonstrated severely combative behavior with high risk of harm; or had contraindications to bright light therapy (manic disorders, severe eye disorders, photosensitive skin disorders, or use of photosensitizing medications). Patients with respiratory or contact precautions, and those with verbal refusal of GMU admission by family/patient/attending physician were also excluded. Patients who were prematurely transferred out of the GMU (for reasons such as instability of medical conditions requiring intensive monitoring, or new requirement of contact precautions) were excluded from subsequent analysis.

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from a National Healthcare Group domain specific review board (DSRB).

Procedure

The GMU consisted of a five-bed unit with a specific elder-friendly room design and lower staff-patient ratios. In addition, core interventions adopted from the HELP program (standardized protocols for managing cognitive impairment, sleep deprivation, immobility, visual impairment, hearing impairment, and dehydration) were systematically administered. Bright light therapy (2000–3000 lux) was administered via lights installed in the ceiling and turned on from 6–10 pm daily. Sleep hygiene principles were also practiced during patients’ GMU stay. All interventions were delivered in accordance with a semistructured protocol, by trained geriatric nurses in GMU, with full (100%) compliance achieved.

We collected data on patient demographics (age, gender, race, length of hospital stay [LOS]), duration of delirium [in days], the medical comorbidities and severity of illness (using a modified Charlson Comorbidity IndexCitation35 and modified Severity of Illness Index),Citation36 and the precipitating causes of delirium. Cognitive status was assessed using a locally validated Chinese Mini–Mental State Examination (CMMSE)Citation37 and functional status using a modified Barthel Index (MBI),Citation38 both administered by a trained assessor during the initial and predischarge phases of the patient admission. The rate and frequency of chemical restraint use was reviewed. As the GMU was a mechanical restraint–free unit, none of the patients in the GMU were subject to physical restraint. To adjust for the different antipsychotics prescribed, we used chlorpromazine equivalenceCitation39 to assess the total antipsychotic usage during the admission and also charted the frequency of benzodiazepine use.

Cognitive assessment

All patients underwent a detailed cognitive evaluation by the consultant geriatrician (specializing in cognitive and memory disorders) upon admission to the GMU. A family member or other designated caregiver was routinely interviewed to establish the patient’s baseline cognitive functioning prior to the current admission. The medical records of all patients were reviewed to ascertain whether a diagnosis of dementia had been previously established. In patients yet to be diagnosed, a diagnosis of dementia was made in the current admission if the corroborative history suggested presence of cognitive symptoms consistent with DSM-IV criteria for dementiaCitation40 of at least 6-months duration, in accordance with the standardized process for cognitive evaluation.Citation41

Sleep data collection

Eight specially-trained GMU nurses completed hourly patient sleep logs during the subjects’ stay in the GMU, as part of routine clinical care. The total sleep time (TST), number of awakenings, number of sleep bouts (SB), and the length of each SB was computed from the 24-hour sleep log data on admission and discharge from the GMU.

Statistical analysis

We evaluated the clinical characteristics, cognitive assessment scores, functional status, and the use of pharmacological agents for the entire cohort of GMU patients and compared among delirium subtypes, using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction and Chi-square tests for the continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Sleep parameters for the whole group and delirium subtypes were computed and the differences in the sleep data on discharge and admission were compared using paired-sample t-tests. We additionally analyzed the sleep parameters, adjusted for comorbidities, delirium days, and chemical restraint use. Statistical significance was taken to be P < 0.05.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Demographics

A total of 228 patients were included in the analyses. We excluded 16 subjects who failed screening criteria, 26 subjects whose family members declined GMU admission, and 31 subjects who were prematurely transferred out of GMU due to their medical condition. There were no age, gender, or ethnic differences between the study group and those excluded from the analyses. The majority of patients had hyperactive delirium (n = 117), followed by mixed delirium (n = 69) and hypoactive delirium (n = 42). The mean age was 84.2 ± 7.4 years, and participants were predominantly female (56.4%) and of Chinese ethnicity (88.2%). There were no significant age, gender, or racial differences between the delirium subtypes ().

Table 1 Clinical characteristics, cognitive and functional outcomes in GMU patients (n = 228) at baseline

Patients with the hyperactive delirium subtype had significantly fewer comorbidities compared with those with hypoactive and mixed delirium (mean Charlson Comorbidity Index score 1.9, 2.9, and 2.5, respectively). Those with hyperactive delirium also had a significantly shorter mean duration of delirium (5.8 ± 3.1 days) compared with those with hypoactive and mixed delirium (7.3 ± 6.0 and 7.9 ± 5.6 days respectively). However, there were no significant differences in LOS across the delirium subtypes.

There were no significant differences in the prevalence of background dementia or number of precipitating causes of delirium. Sepsis was the predominant precipitating cause of delirium (64%–73.9%) among the delirium subtypes.

CMMSE

Although there were significant differences in CMMSE scores among the delirium subtypes on admission and discharge, there was no significant difference in the extent of improvement on the CMMSE nor in any of the delirium indicators among the delirium subtypes upon further analyses.

Functional status

There was significant improvement in functional status (MBI) at discharge, especially in the hyperactive and mixed delirium subtype (19.6 ± 18.6 and 19.0 ± 18.4 for the hyperactive and mixed delirium subtypes, respectively, compared with 14.0 ± 2.5 for the hypoactive delirium subtype) (P < 0.05).

Restraint and medication use

None of the subjects were physically restrained. There was decremental chemical restraint use across the hyperactive, mixed, and hypoactive delirium subtypes (47.9%, 43.5%, and 9.5%, respectively) (P < 0.001). However, benzodiazepine use exhibited a different decremental trend across the mixed, hyperactive, and hypoactive delirium subtypes (30.4%, 26.5%, and 9.5% respectively) (P = 0.23). (see ).

Sleep

All delirium subtypes showed significant improvement in the DRS sleep–wake disturbance subscore at discharge (). The GMU cohort also exhibited significant improvement in sleep parameters at discharge from the GMU compared with baseline, with increased TST (7.7 ± 2.5 hours versus 7.1 ± 2.9 hours) (P < 0.01), increased length of first SB (5.9 ± 3.6 hours versus 5.3 ± 3.7 hours) (P < 0.01), decreased number of SB (1.57 ± 0.8 versus 1.59 ± 0.9) (P < 0.01), and fewer number of awakenings (0.6 ± 0.8 versus 0.7 ± 0.8) (P = 0.03) (see ). In the subgroup analyses of delirium subtypes, there was a significant increase in TST (7.4 ± 2.4 hours versus 6.7 ± 2.8 hours) (P < 0.01) and decreases in number of SB (1.6 ± 0.8 versus 1.7 ± 0.9) (P < 0.01) and length of first SB (5.7 ± 3.4 versus 4.9 ± 3.5) (P = 0.002) for hyperactive delirium subtype. For hypoactive delirium, there was a small but significant increase in TST (7.8 ± 3.1 hours versus 7.7 ± 2.7 hours) (P = 0.05) (see ). However, upon adjustment for comorbidity, duration of delirium, and chemical restraint use, the differences were no longer statistically significant for any of the sleep parameters except length of SB in hypoactive delirium ().

Table 2 Sleep parameters for delirium subtypes of GMU patients

Discussion

Our study contributes to the presently still limited literature on sleep outcomes following interventions in delirious older hospitalized adults, with demonstrated improvements in sleep and functional outcomes using bright light therapy as part of a multicomponent intervention program provided in the GMU.

We found significant improvements, with longer TST at night, increased length of the first SB, and decreased number of SBs and thus fewer awakenings in delirious older hospitalized adults admitted to the GMU. The sleep–wake disturbance measured on DRS-subscores also improved, indicating likely consolidation of sleep rhythms. This may be attributed to the increased physical activity, mental stimulation via reorientation, and structured activity programs in the day, along with evening bright light therapy as well as adherence to sleep hygiene principles during the GMU stay.

Of important clinical relevance were the short-term functional improvements, evident in the improvements achieved on MBI for all delirious subtypes, especially in the hyperactive delirium and mixed delirium subtypes. This will promote the geriatric management principles of early intervention and mobilization, and avoidance of physical restraint use, to prevent the complications of hospitalization and immobility.Citation42 The mean LOS of 15.1 ± 9.3 days in the acute hospital setting compares favorably with the 20.9 ± 2.1 days observed for delirious hospitalized older adults prior to the establishment of the GMU (point prevalence survey). The LOS was longer compared with that of US hospitals due to the funding, subvention structure, and models of geriatric care.

Interestingly, we noted phenomenological differences in delirious patients, where background dementia and behavioral issues prior to admission were more common in hyperactive and mixed delirium. This also related to the nonsignificant differences noted in sedative-hypnotic usage during the delirium episode. This interesting phenomenon is yet to be fully understood in delirium, although Cunningham and MacLullichCitation43 suggested delirium could be a maladaptive sickness behavioral response, with psychoneuroimmunological changes occurring with a systemic inflammation (for example infection) to manifest severe deleterious effects on brain function (during old age or in the presence of neurodegenerative disease). It was not unexpected that cognitive scores and DRS rating remained impaired despite a clinical impression of delirium resolution and adequate treatment of acute precipitating factors, thus supporting the concept of subsyndromal delirium,Citation44 even in the resolution stage, and the findings of longer-term cognitive impairment following a delirium episode.

There were some limitations to this study. Since all patients were given the treatment protocol, there was no control group. These results need to be replicated in a randomized controlled study. Sleep parameters were collected via nurse observations through 24-hour sleep logs, with no objective data collected. However, this was a specialized unit with trained GMU nurses completing the sleep logs thus decreasing the risk of observer bias. We were not able to examine circadian activity rhythm changes without the use of wrist actigraphy and therefore could not ascertain whether this multicomponent program would restore rhythms in the delirious hospitalized elderly. Lastly, given that the interventions were performed on all the patients, with 100% compliance, we are not able to accurately delineate the benefits of the individual components of this multicomponent intervention program.

In summary, we have demonstrated improvements in short-term outcomes related to improved function and sleep in delirious hospitalized older adults, in a real-life geriatric setting with bright light therapy as part of a multicomponent delirium program. Longitudinal follow up of cognitive and sleep outcomes and further studies of pharmacologic agents that may help restore sleep and circadian rhythms in delirious hospitalized older adults and the delirium subtypes would facilitate further understanding of this complex phenomenon.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the GMU nurses and multidisciplinary team involved in the GMU.

This study was funded by FY2010 Ministry of Health Quality of Improvement Funding (MOH HQIF) “Optimising Acute Delirium Care in Tan Tock Seng Hospital” (Grant No HQIF 2010/17). CMS is supported by the National Healthcare Group (NHG) Clinician Scientist Career Scheme 2012/12002.

Disclosure

Dr Ancoli-Israel received a loan of light boxes from Lightbook, Inc for other research she is conducting. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AgnostiniJVInouye Sk. DeliriumHazzardWRBlassJPHalterJBOuslanderJGTinettiMEPrinciples of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology5th edNew YorkMcGraw-Hill200315031515

- InouyeSKDelirium in hospitalized older patientsClin Geriatr Med19981447457649799477

- MograssMAGuillemFBrazzini-PoissonVGodboutRThe effects of total sleep deprivation on recognition memory processes: a study of event-related potentialNeurobiol Learn Mem200991434335219340944

- FisherSThe microstructure of dual-task interaction. Sleep deprivation and the control of attentionPerception1980933273377454513

- FeedmanNSGazendamJLevalLPackAISchwabRJAbnormal sleep/wake cycles and the effect of environmental noise on sleep disruption in the intensive care unitAm J Respir Crit Care Med2001163245145711179121

- GaborJYCooperABCrombackSAContribution of the intensive care unit environment to sleep disruption in mechanically ventilated patients and healthy subjectsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2003167570871512598213

- ColeMGPrimeauFJPrognosis of delirium in elderly hospital patientsCMAJ1993149141468319153

- MoranJADorevitchMIDelirium in the hospitalised elderlyAust J Hosp Pharm2001313540

- MurrayAMLevkoffSEWetleTTAcute delirium and functional decline in the hospitalized elderly patientJ Gerontol1993485M181M1868366260

- InouyeSKViscoliCMHorwitzRIHurstLDTinettiMEA predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristicsAnn Int Med199311964744818357112

- McAvayGJVan NessPHBogardusSTJrOlder adults discharged from the hospital with delirium: 1-year outcomesJ Am Geriatr Soc20065481245125016913993

- LeslieDLZhangYBogardusSTHolfordTRLeo-SummersLSInouveSKConsequences of preventing delirium in hospitalized older adults on nursing home costsJ Am Geriatr Soc200553340540915743281

- ChongMSChanMPKangJHanHCDingYYTanTLA new model of delirium care in the acute geriatric setting: geriatric monitoring unitBMC Geriatr2011114121838912

- FlahertyJHTariqSHRaghavanSBakshiSMoinuddinAMorleyJEA model for managing delirious older inpatientsJ Am Geriatr Soc20035171031103512834527

- LunströmMEdlundAKarlssonBrännströmBBuchtGGustafsonYA multifactorial intervention program reduces the duration of delirium, length of hospitalization, and mortality in delirious patientsJ Am Geriatr Soc200553462262815817008

- PitkäläKHLaurilaJVStrandbergTETilvisRSMulticomponent geriatric intervention for the elderly inpatients with delirium: a randomized, controlled trialJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200661217618116510862

- PitkalaKHLaurilaJVStrandbergTEKautiainenHSintonenHTilvisRSMulticomponent geriatric intervention for elderly inpatients with delirium: effects on costs and health-related quality of lifeJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2008631566118245761

- InouyeSKBogardusSTJrCharpentierPAA Multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patientsN Engl J Med1999340966967610053175

- InouyeSKBogardusSTJrBakerDILeo-SummersLCooneyLMJrThe Hospital Elder Life Program: A model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital Elder Life ProgramJ Am Geriatr Soc200048121697170611129764

- InouyeSKBakerDIFugalPBradleyEHHELP Dissemination ProjectDissemination of the Hospital Elder Life Program: implementation, adaptation, and successesJ Am Geriatr Soc200654101492149917038065

- BradleyEHWebsterTRSchlesingerMBakerDInouyeSKPatterns of diffusion of evidence-based clinical programmes: a case study of the Hospital Elder Life ProgramQual Saf Health Care200615533433817074869

- RubinFHWilliamsJTLescisinDAMookWJHassanSInouyeSKReplicating the Hospital Elder Life Program in a community hospital and demonstrating effectiveness using quality improvement methodologyJ Am Geriatr Soc200654696997416776794

- CohenSRSteinerWMountBMPhototherapy in the treatment of depression in the terminally illJ Pain Symptom Manage1994985345367852760

- LevitanRDWhat is the optimal implementation of bright light therapy for seasonal affective disorder (SAD)?J Psychiatry Neurosci20053017215645001

- Ancoli-IsraelSMartinJLKripkeDFMarlerMKlauberMREffect of light treatment on sleep and circadian rhythms in demented nursing home patientsJ Am Geriatr Soc200250228228912028210

- BurnsAAllenHTomensonBDuignanDByrneJBright light therapy for agitation in dementia: a randomized controlled trialInt Psychogeriatr200921471172119323872

- GammackJKLight therapy for insomnia in older adultsClin Geriatr Med200824113914918035237

- MartinJLMarlerMRHarkerJOJosephsonKRAlessiCAA multicomponent nonpharmacological intervention improves activity rhythms among nursing home residents with disrupted sleep/wake patternsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2007621677217301040

- FetveitABjorvatnBBright-light treatment reduces actigraphic-measured daytime sleep in nursing home patients with dementia: a pilot studyAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200513542042315879592

- Ancoli-IsraelSGehrmanPMartinJLShochatIncreased light exposure consolidates sleep and strengthens circadian rhythms in severe Alzheimer’s disease patientsBehav Sleep Med200311223615600135

- SkjerveAHolstenFAarslandDBjorvatnBNygaardHAJohansenIMImprovement in behavioral symptoms and advance of activity acrophase after short-term bright light treatment in severe dementiaPsychiatry Clin Neurosci200458434334715298644

- OnoHToguchiTKidoYFujinoYDokiYThe usefulness of bright light therapy for patients after oesophagectomyIntensive Crit Care Nurs201127315816621511473

- InouyeSKvan DyckCHAlessiCABalkinSSiegalAPHorwitzRIClarifying confusion: the Confusion Assessment Method. A new method for detection of deliriumAnn Intern Med1990113129419482240918

- TrzepaczPTMittalDTorresRKanaryKNortonJJimersonNValidation of the Delirium Rating Scale-revised-98: comparison with the delirium rating scale and the cognitive test for deliriumJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci200113222924211449030

- CharlsonMEPompeiPAlesKLMacKenzieCRA new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validationJ Chronic Dis19874053733833558716

- WongWCSahadevanSDingYYTanHNChanSPResource consumption in hospitalised, frail older patientsAnn Acad Med Singapore2010391183083621165521

- SahadevanSLimPPTanNJChanSPDiagnostic performance of two mental status tests in the older Chinese: influence of education and age on cut-off valuesInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200015323424110713581

- MahoneyFIBarthelDWFunctional Evaluation: The Barthel IndexMd State Med J196514616514258950

- AtkinsMBurgessABottomleyCMassinoRChlorpromazine equivalents: a consensus of opinion for both clinical and research applicationsPsychiatr Bull199721224226

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association1994

- ChongMSSahadevanSAn evidence-based clinical approach to the diagnosis of dementiaAnn Acad Med Singapore200332674074814716941

- CreditorMCHazards of hospitalization of the elderlyAnn Intern Med199311832192238417639

- CunninghamCMaclullichAMAt the extreme end of the psychoneuroimmunological spectrum: delirium as a maladaptive sickness behaviour responseBrain Behav Immun20132811322884900

- TrzepaczPTFrancoJGMeagherDJPhenotype of subsyndromal delirium using pooled multicultural Delirium Rating Scale – Revised-98 dataJ Psychosom Res2012731101722691554