Abstract

The incidence of age-related eye diseases is expected to rise with the aging of the population. Oxidation and inflammation are implicated in the etiology of these diseases. There is evidence that dietary antioxidants and anti-inflammatories may provide benefit in decreasing the risk of age-related eye disease. Nutrients of interest are vitamins C and E, β-carotene, zinc, lutein, zeaxanthin, and the omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid. While a recent survey finds that among the baby boomers (45–65 years old), vision is the most important of the five senses, well over half of those surveyed were not aware of the important nutrients that play a key role in eye health. This is evident from a national survey that finds that intake of these key nutrients from dietary sources is below the recommendations or guidelines. Therefore, it is important to educate this population and to create an awareness of the nutrients and foods of particular interest in the prevention of age-related eye disease.

Keywords:

Introduction

The number of Americans age 55 years and older will almost double between now and 2030, from 60 million to 108 million (http://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p25-1138.pdf). This age-group suffers an increased incidence of age-related diseases, including such eye diseases as cataract, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Attention has focused on efforts to stop the progression of eye diseases or to prevent the damage leading to these conditions. Nutritional intervention is becoming recognized as a part of these efforts. Compared to most other organs, the eye is particularly susceptible to oxidative damage due to its exposure to light and high metabolism. Recent literature indicates that nutrients important in vision health include vitamins and minerals with antioxidant functions (eg, vitamins C and E, carotenoids [lutein, zeaxanthin, β-carotene], zinc),Citation1 and compounds with anti-inflammatory properties (omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA], docosahexaenoic acid [DHA]))Citation2 may ameliorate the risk for age-related eye disease. A recent survey conducted by the Ocular Nutrition Society found that 70% of the current population (baby boomers) in the age-range 45–65 years ranked vision as the most important of the five senses, yet well over half of those surveyed were not aware of the important nutrients that play a key role in eye health.Citation3

The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS), sponsored by the federal government’s National Eye Institute, found that supplementation with vitamins C and E, β-carotene, zinc, and copper () at levels well above the recommended daily allowances reduced the risk of developing advanced AMD by about 25%.Citation4 Copper was added to prevent copper-deficiency anemia, a condition associated with high levels of zinc intake.Citation5 Based on these results, the AREDS formulation is considered the standard of care for those at high risk for advanced AMD. The dietary information from AREDS pointed to the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin and the omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA as being protective against developing AMD.Citation6,Citation7 AREDS2 (www.nei.nih.gov/areds2), a multicenter phase III randomized clinical trial, accessed the effects of oral supplementation of macular xanthophylls, lutein + zeaxanthin, and/or EPA + DHA as a treatment for cataract, AMD, and moderate vision loss. In secondary analysis, lutein and zeaxanthin supplements on top of the AREDS supplement lowered the progression to advanced AMD in persons with low dietary lutein and zeaxanthin.Citation8

Table 1 Nutrient content of the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) formulation

The purpose of this paper is to describe the nutrients of interest for age-related vision health and to identify rich dietary sources of these nutrients.

Vitamin C

Vitamin C, also known as ascorbic acid, is an important water-soluble vitamin. Vitamin C is available in many forms, but there is little scientific evidence that any one form is absorbed better or has more activity than another. Most experimental and clinical research uses ascorbic acid or sodium ascorbate. Natural and synthetic l-ascorbic acid are chemically identical, and there are no known differences in their biological activities or bioavailabilities.Citation9

Vitamin C is required for the synthesis of collagen, an important structural component of blood vessels, tendons, ligaments, and bone.Citation10 Vitamin C is also a highly effective antioxidant, protecting essential molecules in the body, such as proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, DNA, and RNA, from damage by free radicals and reactive oxygen species that can be generated during normal metabolism as well as through exposure to toxins and such pollutants as cigarette smoke. The eye has a particularly high metabolic rate, and thus has an added need for antioxidant protection. Plasma concentrations of vitamin C, an indicator of intake, are related to levels in the eye tissue.Citation11 In the eye, vitamin C may also be able to regenerate other antioxidants, such as vitamin E.Citation12

The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for vitamin C is 75 mg/day for women (≥ 19 years old) and 90 mg/day for men (≥ 19 years old).Citation10 Based on the intake data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES),Citation13 the average intake of vitamin C from foods in the US for men and women over 50 years of age is 93 and 88 mg/day, respectively (). However, men in the 50th percentile or below for vitamin C intake from diet and women in the 25th percentile or below have intakes that are less than the RDA (). Vitamin C-rich foods and some suggested serving sizes are shown in .

Table 2 Intake in men (n = 1178) and women (n = 1215) over 50 years of age (mg) based on NHANES 2009–10

Table 3 Vitamin C content of foodsCitation43,Table Footnote*

Vitamin E

The term “vitamin E” describes a family of eight fat-soluble antioxidants: four tocopherols (α-, β-, γ-, and δ-) and four tocotrienols (α-, β-, γ-, and δ-). α-Tocopherol is the form of vitamin E that is actively maintained in the human body and also the major form in blood and tissues.Citation14 It is also the chemical form that meets the RDA for vitamin E. The main function of α-tocopherol in humans appears to be that of an antioxidant. Fats, which are an integral part of all cell membranes, are vulnerable to destruction through oxidation by free radicals. α-Tocopherol attacks free radicals to prevent a chain reaction of lipid oxidation. This is important, given that the retina is highly concentrated in fatty acids.Citation2 When a molecule of α-tocopherol neutralizes a free radical, it is altered in such a way that its antioxidant capacity is lost. However, other antioxidants, such as vitamin C, are capable of regenerating the antioxidant ability of α-tocopherol.Citation15

Other functions of α-tocopherol that would be of benefit to ocular health include effects on the expression and activities of molecules and enzymes in immune and inflammatory cells. Furthermore, α-tocopherol has been shown to inhibit platelet aggregation and to improve vasodilation.Citation10,Citation16

The RDA for vitamin E is 15 mg/day α-tocopherol for both women and men (≥19 yrs).Citation10 The average intake of vitamin E from foods in the US for men and women over 50 years of age is 8.6 and 7.3 mg/day, respectively (). Only men and women in the 95th percentile of vitamin E intake or greater have intakes of vitamin E from diet that meet the RDA. Vitamin E-rich foods and some suggested serving sizes are shown in .

Table 4 Vitamin E content of foodsCitation43,Table Footnote*

β-carotene

β-Carotene is an orange pigment commonly found in fruits and vegetables and belongs to a class of compounds called carotenoids. Among the carotenoids, β-carotene is the primary dietary source of provitamin A.Citation17 The best evidence that β-carotene may play a role in age-related eye disease comes from the AREDS1 trial, in which supplementation with β-carotene along with vitamins C and E, zinc, and copper reduced the risk of developing advanced AMD.Citation4 The amount of β-carotene in this intervention was 17 mg (28,640 IU vitamin A) (), a level that is above the 99th percentile of dietary intakes for both men and women 50 years and older (). There is no RDA for β-carotene. Data from various populations suggest that 3–6 mg/day of β-carotene from food sources is prudent to maintain plasma β-carotene concentrations in the range associated with a lower risk of various chronic diseases.Citation10 The average intake of β-carotene from foods in the US for men and women over 50 years of age is 2.6 and 2.7 mg/day, respectively (). β-Carotene-rich foods and some suggested serving sizes are shown in .

Table 5 β-Carotene content of foodsCitation44,Table Footnote*

While very high intake of dietary β-carotene is considered to have no adverse affects on health, there should be caution when supplementing with levels well beyond what can be achieved from dietary sources for those at risk for lung cancer. The effect of β-carotene supplementation on the risk of developing lung cancer was examined in two large randomized, placebo-controlled trials. The Alpha-Tocopherol Beta-Carotene (ATBC) cancer-prevention trial evaluated the effects of 20 mg/day of β-carotene and/or 50 mg/day of α-tocopherol on male heavy smokers.Citation18 The Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial (CARET) evaluated the effects of a combination of 30 mg/day of β-carotene and 25,000 IU/day of retinol (vitamin A) in men and women who were smokers, former smokers, or had a history of occupational asbestos exposure.Citation19 Unexpectedly, the risk of lung cancer in the groups taking β-carotene supplements was increased by 16% after 6 years in ATBC and increased by 28% after 4 years in CARET. The reasons for the increase in lung cancer risk are thought to be due to the pro-oxidant effects of high doses of β-carotene in an oxidative stressed environment, such as a smoker’s lung.Citation20

Zinc

Zinc is important in maintaining the health of the retina, given that zinc is an essential constituent of many enzymesCitation5 and needed for optimal metabolism of the eye. Zinc ions are present in the enzyme superoxide dismutase, which plays an important role in scavenging superoxide radicals. As related to the eye, zinc plays important roles in antioxidant and immune function. Zinc also plays an important role in the structure of proteins and cell membranes. The structure and function of cell membranes are also affected by zinc. Loss of zinc from biological membranes increases their susceptibility to oxidative damage and impairs their function.Citation21 Zinc also plays a role in cell signaling and has been found to influence nerve-impulse transmission.

The RDA for zinc is 11 mg/day for men and 8 mg/day for women (≥19 yrs).Citation5 The average intake of zinc from foods in the US for men and women over 50 years of age is meeting this requirement, with averages of 13.5 and 9.8 mg/day, respectively (). However, men and women in the 25th percentile of zinc intake have intakes of dietary zinc that do not meet the RDA. Zinc absorption is lower in individuals consuming vegetarian diets; it is recommended that the zinc requirement for this group be twice as much as for nonvegetarians.Citation5 Foods rich in zinc and some suggested serving sizes are shown in .

Table 6 Zinc content of foodsCitation43

Lutein and zeaxanthin

Lutein and zeaxanthin are carotenoids found in high quantities in green leafy vegetables. Unlike β-carotene, these two carotenoids do not have vitamin A activity.Citation22 Of the 20–30 carotenoids found in human blood and tissues,Citation23 only lutein and zeaxanthin are found in the lens and retina.Citation24,Citation25 Lutein and zeaxanthin are concentrated in the macula or central region of the retina, and are referred to as macular pigment. In addition to their role as antioxidants, lutein and zeaxanthin are believed to limit retinal oxidative damage by absorbing incoming blue light and/or quenching reactive oxygen species.Citation26 While there is no RDA for lutein and zeaxanthin, intakes of approximately 6 mg/day have been associated with a decreased risk of AMD.Citation27 The current intakes of lutein and zeaxanthin among adults >50 years of age falls well below this level, with average intake of <2 mg/day for both men and women (). Only men in the 99th percentile of lutein/zeaxanthin intake and women in the 95th percentile meet the dietary intakes that have been related to decreased risk of AMD. In general, lutein and zeaxanthin are found in many of the same foods, and most dietary databases include them together. Because there has been discussion on their individual roles in eye health, Perry et al have analyzed lutein and zeaxanthin separately in food.Citation28 Lutein- and zeaxanthin-rich foods and some suggested serving sizes are shown in .

Table 7 Lutein/zeaxanthin content of foodsCitation44,Table Footnote*

Omega-3 fatty acids

In addition to the antioxidants cited above, the omega-3 fatty acids DHA and EPA are thought to be important in AMD prevention. The omega-3 fatty acids have a number of actions that provide neuroprotective effects in the retina. This includes modulation of metabolic processes affecting oxidative stress, inflammation, and vascularization.Citation2 DHA is a key fatty acid found in the retina, and is present in large amounts in this tissue.Citation29 Tissue DHA status affects retinal cell-signaling mechanisms involved in phototrans-duction.Citation2 It has been suggested that atherosclerosis of the blood vessels that supply the retina contributes to the risk of AMD, similar to the mechanism involved in coronary heart disease,Citation30 suggesting that the same dietary fats related to coronary heart disease may also be related to AMD.Citation31,Citation32 In addition, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids may have another role in the function of the retina. Biophysical and biochemical properties of DHA may affect photoreceptor-membrane function by altering permeability, fluidity, thickness, lipid-phase properties, and the activation of membrane-bound proteins.Citation2

There is no RDA for EPA/DHA. As stated above, the protective effects of omega-3 fatty acids in ocular health are thought to be similar to those for heart health. The dietary recommendations set up by the American Heart Association for EPA/DHA are largely based on cardiovascular health. Individuals with no history of coronary heart disease or myocardial infarction are recommended to consume oily fish or fish oils two times per week.Citation33 Those having been diagnosed with coronary heart disease after infarction should consume 1 g EPA + DHA per day from oily fish or supplements. The FDA has advised that adults can safely consume a total of 3 g per day of combined DHA and EPA, with no more than 2 g per day coming from dietary supplements.Citation33

The current intakes for EPA/DHA among men and women >50 years of age are 121 and 13 mg/day, respectively (). EPA/DHA-rich foods and some suggested serving sizes are shown in .

Table 8 EPA + DHA content in fishCitation33

Recommendations

To date, the evaluation of a single nutrient in the prevention of age-related eye diseases has not been entirely consistent. The inconsistencies among studies in terms of which nutrients and the amount of nutrients required for protection make it difficult to make specific recommendations for dietary intakes. It is likely that nutrients are acting synergistically to provide protection. Therefore, it may be more practical to recommend food choices rich in vitamins C and E, β-carotene, zinc, lutein and zeaxanthin, and omega-3 fatty acids. Such a recommendation may also provide benefit from possible other components in food that may be important. Therefore, an awareness of dietary sources of key nutrients important for ocular health is important for both the patient and health-care provider. Good sources of vitamin C include citrus fruit, berries, tomatoes, and broccoli (). Good sources of vitamin E are vegetable oils, wheat germ, nuts, and legumes (). β-Carotene can be found in carrots, apricots, sweet potatoes, and pumpkins (). Oysters, beef, and other meats are rich sources of zinc. Nuts, legumes, and dairy are relatively good plant sources of zinc (). The two foods that were found to have the highest amounts of lutein and zeaxanthin were kale and spinach (). Other major sources include broccoli, peas, and brussels sprouts. Fish oils are the primary source of omega-3 fatty acids ().

A healthy diet including a variety of fresh fruit and vegetables, legumes, lean meats, dairy, fish, and nuts, will have many benefits and will be a good source of the antioxidant vitamins and minerals implicated in the etiology of age-related eye health. There is no evidence that nutrient-dense diets high in these foods, which provide known and unknown antioxidant components, are harmful. In fact, intake of fruits, vegetables, and legumes is associated with reduced risk of death due to cancer, cardiovascular disease, and all causes.Citation34–Citation36 Such a dietary recommendation does not appear to be harmful and may have other benefits, despite its unproven efficacy in preventing or slowing age-related eye disease. Furthermore, the hypothesis that antioxidant and anti-inflammatory nutrients may be of benefit in age-related eye health is plausible, given the role of oxidative damage and inflammation in the etiology of age-related eye diseases.

The AREDS1 trial found that supplementation with vitamins C and E, β-carotene, zinc, and copper reduces the risk of developing advanced AMD. Based on the supporting literature, including observations from AREDS1, AREDS2 will evaluate lutein, zeaxanthin, and the omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA on reducing the risk of advanced AMD. Although AREDS1 supports a role for these nutrients in AMD, it is reasonable to believe that they are also important for the prevention or treatment of other major age-related eye diseases, given the role of oxidative stress and inflammation in their etiologies.Citation37 In fact, the American Academy of Ophthalmology has developed guidelines for the use of omega-3 fatty acids for potential benefit in dry eye.Citation38 Dietary data from NHANES indicate that the intake of the key ocular nutrients may be inadequate in those ≥50 years of age. This gap may be filled by creating an awareness of these nutrients and their dietary sources. Therefore, an educational tool may be useful to aid in the selection of food/nutrient choices for optimal eye health.

Efforts at nutrition and eye-health education

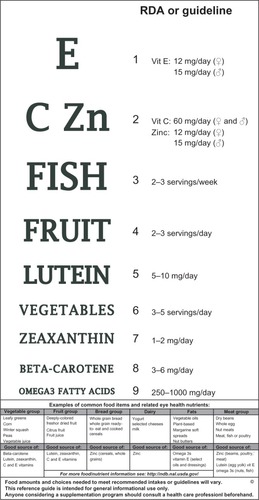

As previously discussed, there have been a number of important studies affirming the relationship of diet to the treatment, prevention, and/or slowing progression of a variety of age-related ocular illnesses. Educational campaigns have been initiated by the federal government and public health associations as well as the eye-vision industry to heighten the awareness of a link between nutrition and eye-health link.Citation39–Citation42 To this end, an educational vision icon (M’eyeDiet, ) was developed to promote awareness of the importance of a healthy diet, targeting the aforementioned eye-health nutrients.

This graphic presents a suggested recommended daily intake for each nutrient. This poster can be placed in medical clinics, senior centers/assisted living areas, optometrist and ophthalmologist offices, wellness centers and food supermarkets, as well as being posted in a personal health-reminder area of one’s home. Since nutrients are more conceptual, and hence are invisible to consumers, “good vision food” items and the correct food serving size information should be available to the client/patient/consumer to make the necessary translation from nutrients to food.

A simple food guide to help individuals choose rich food sources as a tear-off page attached to the graphic itself or as a stand-alone pamphlet can be included to encourage the discussion and practice of selecting the best food choices for healthy vision. The guide shown here is formed based on food groupings (vegetables, fruits, breads, dairy, fats, meats [meat and nonmeat high-protein sources]). Anyone considering a supplementation program to meet recommended intakes should consult a health-care professional beforehand.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Huifen Wang, PhD for his assistance on NHANES data retrieval and Emily S Mohn, BS for her assistance with the organization of the NHANES data. This study was supported by USDA 58-1950-7-707, Bausch and Lomb and the contribution to the research of H.M.R. of an anonymous donor. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the view of the US Department of Agriculture.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ChiuCJTaylorANutritional antioxidants and age-related cataract and maculopathyExp Eye Res20078422924516879819

- SanGiovanniJPChewEYThe role of omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in health and disease of the retinaProg Retin Eye Res2005248713815555528

- Ocular Nutrition SocietyBaby boomers value vision more than any other sense but lack focus on eye health2011 Available from: http://www.ocularnutritionsociety.org/boomersAccessed September 21, 2012

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research GroupA randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no 8Arch Ophthalmol200111914171436 Erratum in Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:125111594942

- Panel on Micronutrients Subcommittees on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients and of Interpretation and Use of Dietary Reference Intakes, Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference IntakesDietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and ZincWashingtonNational Academies Press2002

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research GroupSanGiovanniJPChewEYThe relationship of dietary carotenoid and vitamin A, E and C intake with age-related macular degeneration in a case-control study: AREDS report no 22Arch Ophthalmol20071251225123217846363

- SangiovanniJPAgrónEMelethADω-3 Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and 12-y incidence of neovascular age-related macular degeneration and central geographic atrophy: AREDS report 30, a prospective cohort study from the Age-Related Eye Disease StudyAm J Clin Nutr2009901601160719812176

- The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) Research GroupLutein + zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids for age-related macular degeneration. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) Randomized Clinical TrialJAMA2013309192005201523644932

- GregoryJF3rdAscorbic acid bioavailability in foods and supplementsNutr Rev1993513013038302486

- Panel on Dietary Antioxidants and Related Compounds, Subcommittee on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients, Subcommittee on Interpretation and Uses of DRIs, Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference IntakesDietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and CarotenoidsWashingtonNational Academies Press2000

- TaylorAJacquesPFNowellTVitamin C in human and guinea pig aqueous, lens and plasma in relation to intakeCurr Eye Res1997168578649288446

- CarrACFreiBToward a new recommended dietary allowance for vitamin C based on antioxidant and health effects in humansAm J Clin Nutr1999691086110710357726

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionNational Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm2013Accessed May 21, 2013

- TraberMGUtilization of vitamin EBiofactors19991011512010609871

- TraberMGVitaminEShilsMEShikeMRossACCaballeroBCousinsRJModern Nutrition in Health and DiseasePhiladelphiaLippincott Williams & Wilkins2006396411

- TraberMGDoes vitamin E decrease heart attack risk? Summary and implications with respect to dietary recommendationsJ Nutr2001131395S397S11160568

- KrinskyNIJohnsonEJCarotenoid actions and their relation to health and diseaseMol Aspects Med20052645951616309738

- [No authors listed]The effect of vitamin E and beta-carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study GroupN Engl J Med1994330102910358127329

- OmennGSGoodmanGEThornquistMDEffects of a combination of beta-carotene and vitamin A on lung cancer and cardiovascular diseaseN Engl J Med1996334115011558602180

- WangXDRussellRMProcarcinogenic and anticarcinogenic effects of beta-caroteneNutr Rev19995726327210568335

- O’DellBLRole of zinc in plasma membrane functionJ Nutr20001301432S1436S10801956

- JohnsonEJThe role of carotenoids in human healthNutr Clin Care20025566512134711

- ParkerRSCarotenoids in human blood and tissuesJ Nutr19891191011022643690

- YeumKJShangFSchalchWRussellRMTaylorAFat-soluble nutrient concentrations in different layers of human cataractous lensCurr Eye Res19991950250510550792

- BoneRALandrumJTTarsisSLPreliminary identification of the human macular pigmentVision Res198525153115353832576

- KrinskyNIPossible biologic mechanisms for a protective role of xanthophyllsJ Nutr2002132540S542S11880589

- SeddonJMAjaniUASperdutoRDDietary carotenoids, vitamins A, C and E, and advanced age-related macular degeneration. Eye Disease Case-Control Study GroupJAMA1994272141314207933422

- PerryARasmussenHJohnsonEJXanthophyll (lutein, zeaxanthin) content in fruits, vegetables and corn and egg productsJ Food Compost Anal200922915

- FlieslerSJAndersonREChemistry and metabolism of lipids in the vertebrate retinaProg Lipid Res198322791316348799

- SarksSHSarksJPAge-related macular degeneration: atrophic formRyanSJSchachatSPMurphyRMRetinaSt Louis (MO)Mosby1994149173

- ChoEHungSSeddonJMNutrition and age-related macular degeneration: a reviewBergerJWFineSLMaquireMGAge-Related Macular DegenerationSt Louis (MO)Mosby19985767

- SnowKKSeddonJMDo age-related macular degeneration and cardiovascular disease share common antecedents?Ophthal Epidemiol19996125143

- Kris-EthertonPMHarrisWSAppelLJFish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular diseaseCirculation20021062747275712438303

- WisemanMThe second World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research expert report. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspectiveProc Nutr Soc20086725325618452640

- NöthlingsUSchulzeMBWeikertCIntake of vegetables, legumes, and fruit, and risk for all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality in a European diabetic populationJ Nutr200813877578118356334

- LawMRMorrisJKBy how much does fruit and vegetable consumption reduce the risk of ischaemic heart disease?Eur J Clin Nutr1998525495569725654

- VishwanathanRJohnsonEJEye diseaseErdmanJWMacDonaldIAZeiselSHPresent Knowledge in Nutrition10th edAmes (IA)Wiley-Blackwell2012

- American Academy of OphthalmologyPreferred Practice Pattern guidelines. Dry-eye syndrome: limited revision Available from: http://one.aao.org/CE/PracticeGuidelines/PPP_Content.aspx?cid=127dbdce-4271-471a-b6d9-464b9d15b748Accessed January 22, 2013

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionVision Health Initiative (VHI) [website] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/visionhealthAccessed November 24, 2012

- National Eye InstituteNational Eye Health Education Program: Vision and aging Available from: http://www.nei.nih.gov/nehep/programs/visionandaging/index.aspAccessed November 24, 2012

- Bausch and LombThe Joy of Sight [website] Available from: http://www.alcon.com/eye-health/vision-problems.aspxAccessed November 24, 2012

- AlconThe world of eye health Available from: http://www.alcon.com/eye-health/vision-problems.aspxAccessed May 21, 2013

- US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research ServiceUSDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference2010 Available from: http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=8964Accessed May 21, 2013

- US Department of AgricultureUSDA-NCC Carotenoid Database for US Foods – 1998 Available from: https://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2User-Files/Place/12354500/Data/SR25/nutrlist/sr25a338.pdfAccessed November 1, 2012