Abstract

Purpose

To study the feasibility of first, reaching functionally declined, but still independent older persons at risk of falls through their general practitioner (GP) and second, to reduce their physiological and psychological fall risk factors with a complex exercise intervention. We investigated the effects of a 16-week exercise intervention on physiological (function, strength, and balance) and psychological (fear of falling) outcomes in community-dwelling older persons in comparison with usual care. In addition, we obtained data on adherence of the participants to the exercise program.

Methods

Tests on physical and psychological fall risk were conducted at study inclusion, and after the 16-week intervention period in the GP office setting. The 16-week intervention included progressive and challenging balance, gait, and strength exercise as well as changes to behavioral aspects. To account for the hierarchical structure in the chosen study design, with patients nested in GPs and measurements nested in patients, a three-level linear mixed effects model was determined for analysis.

Results

In total, 33 GPs recruited 378 participants (75.4% females). The mean age of the participants was 78.1 years (standard deviation 5.9 years). Patients in the intervention group showed an improvement in the Timed-Up-and-Go-test (TUG) that was 1.5 seconds greater than that showed by the control group, equivalent to a small to moderate effect. For balance, a relative improvement of 0.8 seconds was accomplished, and anxiety about falls was reduced by 3.7 points in the Falls Efficacy Scale–International (FES-I), in the intervention group relative to control group. In total, 76.6% (N = 170) of the intervention group participated in more than 75% the supervised group sessions.

Conclusion

The strategy to address older persons at high risk of falling in the GP setting with a complex exercise intervention was successful. In functionally declined, community-dwelling, older persons a complex intervention for reducing fall risks was effective compared with usual care.

Introduction

In community-dwelling older persons, falls pose a major threat to function and independence. Falls are a common cause for nursing home admission and health care utilization in this population.Citation1–Citation3 It is a common understanding that about 30% of persons 65 years and older experience a fall at least once a year, with a high percentage of these persons even falling several times per year.Citation2,Citation4 The incidence of falls, as well as fall-related injuries, increases with age.Citation4,Citation5 Therefore, fall prevention is an important component in a society facing an increasing fall-related burden on the public health care system.Citation6

Clinical trials have shown that effective fall prevention interventions include balance training in combination with strength training.Citation1,Citation6,Citation7 In contrast to this evidence, the implementation of broad ranging fall prevention programs is rare, and the challenge remains to deliver the most effective intervention to the right target group of older persons.Citation8

The implementation process for effective intervention strategies is hampered by different barriers. One important barrier is the attitude of the older person him- or herself, and the other barrier might be the pathway of the implementation process. Research has demonstrated that over 50% of older persons offered an exercise program for fall prevention refused to take part,Citation9 and uptake rates are sometimes less than 10%.Citation10,Citation11 To increase the uptake rate, different strategies are feasible. One strategy could be to utilize the pathway of the general practitioner (GP) office setting to target at-risk older persons. GPs might be the key persons to motivate at-risk older persons to participate in exercise programs for multiple reasons: research has demonstrated that older persons see their GP on a regular basis, view their GP as a very important source of health-related information, and value their advice.Citation12 GPs are mostly familiar with the daily routine and needs of their older patients, but in contrast, only few studies have investigated fall prevention programs in the GP setting.Citation13 For German GPs, the Geriatric recommendations dictate thatCitation14 in persons 65 years and older, fall history during the past 6 months should be assessed at least once each year. A recent study in Germany found that 83% of the GPs were unaware of the recent falls of their patients in the previous 6 months.Citation15 These results illustrate the need to include GPs in fall prevention research targeting older persons at high risk of falling.

In this paper, we investigated the effects of a previously validated 16-week complex exercise intervention targeting community-dwelling older persons at high risk of falling, in the GP setting. We compared the effects of the exercise program on physical and psychological fall-risk outcomes in the intervention group (IG) with the group receiving usual care. The outcomes were balance, strength, function, and fear of falling. All fall-risk outcomes were measured at the start of the study and after the 16-week intervention. In addition, we obtained data on adherence to the exercise sessions by the included older persons. Furthermore, this paper presents in-depth information on the complexity and necessity of the exercise program, including the different components of the exercise program and the challenges in the recruitment process, for both the GPs and at-risk patients.

Methods

Study design

The study protocol (PreFalls NCT1032252) we used has been previously published and no changes were made.Citation16 In short, it was a controlled, multicenter, prospective study design with an equal cluster, random allocation of participating GPs to a complex intervention or usual care control group (CG). The effects of the complex 16-week exercise intervention on physical and psychological fall risks outcomes were investigated. The number of falls and rate of fallers at 12 and 24 months postintervention will be obtained. Participating patients of the included GPs were tested at four points: at baseline (T0); after the intervention (T1); 12 months after baseline; and 24 months after baseline. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Board of the Faculty of Medicine of the Technische Universität München. The study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration. In this paper, the effects of the 16-week intervention on fall risk and the physical and psychological outcomes between T0 and T1 were reported.

Participants – recruitment of GPs and cluster randomization

GPs were recruited through local “quality” peer groups, from networks affiliated to the Institute for Family Medicine of the Technische Universität München and by the Institute of Sport Science and Sports of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, as well as through additional advertisement in German medical journals.Citation16 GPs were invited to participate in the study by an invitation letter, and in case of no reply, contacted via telephone. All the participating GPs took part in an educational workshop lasting 3.5 hours. The workshop provided the GPs and one of their staff members with information regarding the study, including the objectives, definition of falls used in the study, and topics of the intervention. In addition, GPs and their staff members were trained in the testing procedure and management of the fall-risk assessment. GPs gained Continuing Medical Education (CME) points for attending the workshop.Citation16 With regard to implementation of fall risk assessment in the GP setting and sustainability strategies, no incentives were provided for the GPs for study participation and testing procedures (due to the current health systems structure in Germany). After attending the educational workshop, the GPs were randomized either to the intervention or the CG and started to recruit their patients. Randomization was conducted by a blockwise randomization list for both coordination centers, by a statistician who was otherwise uninvolved in the study at the time. Neither the GP nor staff members were blinded to the randomization allocation – blinding for the testing procedure is not feasible in an exercise intervention study because participants in the exercise intervention arm would tell their GPs what they were doing. Cluster randomization was the best solution to avoid contamination of the CG.Citation19

After the randomization process, each GP received a list with the personal identification number IDs for the recruitment of their future participants.

Participants – recruitment of patients

GPs or trained staff members in the participating practices approached eligible functionally declined, community-dwelling patients in their respective settings for participation in the study. The approach was based on self-selection as well as patients records, and final inclusion was based on the objective fall risk assessment.

The inclusion criteria were defined as: aged 65 years and older; reporting one or more falls in the past 12 months and/or fear of falling and/or physical fall risk obtained with the fall risk assessment (described further down); a cutoff score of <10 seconds for the strength and function tests; and self-reported or measured balance impairments.Citation16 At least one inclusion criterion had to be fulfilled to take part in the study. All patients were required to sign informed consent forms before they were tested in their GP’s office setting.Citation16 All participants had to be mobile eg, able to stand alone and walk alone or with an assistant device. Participants could not be wheelchair-bound. Sample size calculations were based on fall reductions and showed that about 382 participants were needed.Citation16

Recruitment of the fall intervention exercise instructors

The intervention instructor was either recruited by the participating GP or by the local study coordinator. The instructor was either an experienced physiotherapist or sports scientist.Citation16 For standardization of the multicenter intervention, all the instructors took part in an 8-hour educational workshop, in which they were trained to apply the standardized complex exercise program, as well as given background information of the study, eg, objective of the study, tests used, and fall definition.Citation16 In contrast to the GPs, the exercise instructors were reimbursed for their sessions, in accordance with the German national standards. To avoid testing bias, the exercise instructors were not involved in the testing procedure. Realization and the subjective experience of the instructors were obtained with a questionnaire after the exercise program ended.

Testing procedure

After signing the informed consent sheet, the eligible patient was tested by the GP or the trained staff member to ensure the inclusion criteria and obtain the base line status. In case of problems with the testing procedure due to a time restriction, the regional coordination team supported the testing process for that specific GP. All GPs collected the testing protocol and data and then sent all the documents via postal service to the regional coordination center. The regional coordination center paid for the postal service and entered the data into the common database. All data management was handled at the coordination centers, in a common database.

Testing in the IG and CG, for physical and psychological fall risk, was conducted at T0 and at T1.

The testing was split between the GPs, who managed medication and chronic diseases, and the trained staff member, who managed the questionnaires and physical performance tests. Each GP setting had one trained staff member who was responsible for the testing procedure throughout the study and to whom the testing material was sent. Each GP received, in addition to the training, a standardized test protocol to ensure the reliability of outcome measurements.

Fall risk assessment

A series of physical performance tests was administered in the GP setting to evaluate the fall risk.Citation16 The Timed Up and Go test (TUG)Citation17, the five repetition Chair Stand Test (CST)Citation18, and a modified Romberg test (mod Rom) were used for physical fall risk assessment. For psychological outcomes, the German version of the Falls Efficacy Scale – International (FES-I) was used.Citation16 The TUG was performed over a 3-meter course, and staff members had to note the use of walking aids in the testing protocol. The participant was asked to walk as fast, but safely as possible. Time was taken in seconds with a stop watch. The five repetitions CST was performed with arms crossed over the chest. The time it took to stand up and sit down five times was measured in seconds by a stopwatch.Citation16 Again, any deviation from the testing protocol had to be noted by the staff member. In case five repetitions were not possible due to the limitation of the participants, the numbers of chair rises had to be reported. The mod Rom measures static balance in three conditions: feet side by side, semitandem, and tandem stance, for ten seconds in each position. Fear of falling was assessed with the German FES-I.Citation16

Intervention

The complex exercise program was based on a formerly established effective exercise program.Citation20,Citation21 It was developed following a biopsychosocial approach, enhancing resources in older, community-dwelling persons.Citation21 Participating patients of the randomized intervention GPs were organized in groups of 5–15 older persons. The intervention included a combination of 28 supervised and unsupervised sessions. Sixteen sessions, once per week for 60 minutes, were supervised, and the participants added at least one unsupervised session starting from week 5. Adherence to each supervised and unsupervised session was taken with a standardized protocol and procedure by the exercise instructors. The supervised interventions took place in a community house, church location, or at the place of the exercise instructor that was near the GP setting. Each supervised session started with a short, 5-minute discussion to introduce the topic of the session and address participants′ well-being and questions, followed by a 10-minute warm up phase, leading to a 30–40 minute conditioning period, followed by a 5–10 minute cooling down and closing phase with relaxation and discussion between the participants and instructors about the experience. During the exercise program, local transportation service was provided for the participants, when necessary to be able to attend the group-based sessions. The group-based intervention followed standardized protocols for comparable conditions, but with as much variety as possible to address the individual needs of participants. A third party insurance was provided to the instructors, as well as to the participants, in case of adverse events.

We defined our exercise intervention as a complex intervention due to the fact that it included several interacting components (some with behavioral aspects) on the part of the exercise instructor as well as the participants, number of groups being targeted by the exercise program, different outcomes, and a high degree of flexibility for tailoring the exercise to the participant’s individual level.Citation19 The complex exercise program () targeted the most important fall-risk factors, balance and gait limitation and muscle strength of the upper and lower extremities. In addition, body awareness, motor coordination, self-efficacy components, and small group dynamics games were included. The exercise was performed mostly in standing position. Modifications to the original exercise programCitation20,Citation21 were made by exercising only with body weight and without additional materials. The strength exercises were performed with increasing progression by changing frequency, speed, and range of movement. Intensity was controlled with the Borg Scale,Citation22 an evaluated self-perceived exhaustion scale, to avoid negative events. The balance exercise included challenging conditions (eg, eyes open versus closed, reduction of base of support), and training regarding postural strategies (ankle, hip, and step strategies). The gait exercise contained different rhythmical, spatial, and temporal components, as well as a dual task condition, eg, walking and talking, and combination of gait and arm movements. At the start of the exercise program, participants were allowed to use walking aids if needed, but throughout the intervention, the use of walking aids during exercise was reduced.

Table 1 Main intervention components and their frequency per group-based intervention

To address the psychological fall risk dimension, sessions for behavioral changes and attitudes were also included in the complex exercise intervention. The sessions on psychological aspects were also part of the formerly evaluated exercise program.Citation21

To sum up, the complex exercise program addressed the biopsychosocial health resources of the participants and empowered their independence by including elements of patient education with regard to behavioral changes.

In order to perform the home-based unsupervised exercises, participants were provided a booklet with written instructions, safety issues, and pictures about how to do the exercise in their home. The booklet included a training schedule, which the participants could use. The exercises in the booklet were introduced in the group-based sessions and were occasionally integrated, as well as recalled, at the end phase of the intervention, to ensure familiarization.

To ensure comparability between the different IGs, close contacts were maintained between the local study coordinator and the instructors. After the intervention, instructors filled out a questionnaire to provide subjective information on their experience in managing the complex intervention program.

The CG did not receive any intervention but continued seeing their GPs with their usual care procedures.

Statistical analyses

The focal interest here was to investigate the effects of the applied intervention on change in general fall risk, expressed in several assessments previously described. To account for the hierarchical structure in the chosen study design with patients nested in GPs and measurements nested in patients, a three-level linear mixed-effects model was determined for analysis. Per considered outcome measure (TUG, CST, mod Rom, FES-I) one model was created, with time and IG as experimental factors. Differences in change over time were represented by the group-by-time-interaction effect, which was the primary interest. None of the four outcome models showed the third level of GPs as relevant in either explaining a notable amount of variance or accomplishing independent identical normal distributed residuals. Hence, two-level models were sufficient to represent the data structure while preserving parsimony. For all four considered outcome measures, a random intercept and random slope model was deemed appropriate. Because there were only two measurements per outcome, linear change from baseline to follow up was fitted saturated, which is comparable to an analysis of covariance, if no random effects were present.

Data were analyzed with R environment for statistical computing (Institute for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

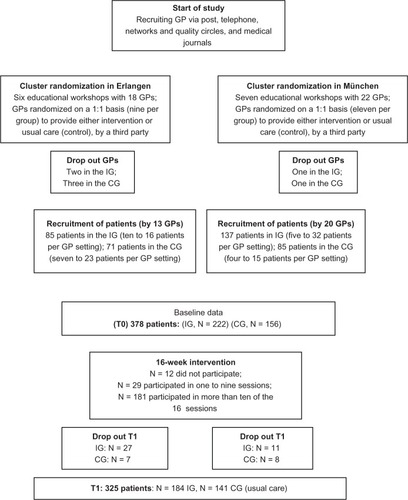

In total, we sent out 896 invitation letters to GPs. Twenty-two GPs (2%) agreed to participate after the invitation letters and personal contact. A further eleven GPs agreed to take part in the study after telephone contact, leading to a total number of 33 GPs. No systematic data was collected on the reason for declining, but in the telephone contact, the most common reasons for not taking part were lack of time, interest, and incentives, which is in line with the reasons provided by an earlier study.Citation12 The 33 GPs recruited 378 participants meeting the inclusion criteria. No systematic data was collected about whether invited patients declined to take part in the study, but reasons reported by GPs to the study coordinators were: regarding group exercise as a burden and not enjoyable, low functional status, caring for spouse or other family members or not viewing themselves as at risk of falls. These arguments are in line with other, systematically collected information.Citation9 shows the flow of the study.

Figure 1 Flowchart of the study.

The characteristics of the patients are presented in . In total, 16 trained exercise instructors provided the exercise intervention in 20 groups.

Table 2 Demographic variables of participants at baseline

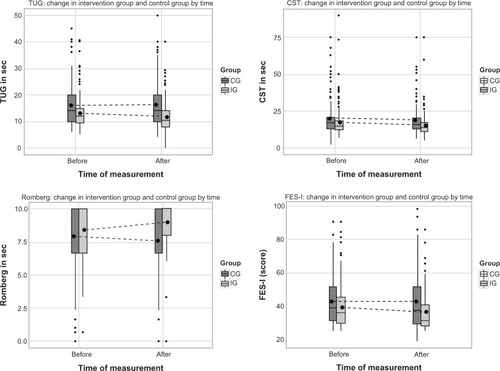

In three of four short-term targeted outcome measures (TUG, mod Rom, FES-I) statistical analysis showed significant differences in the mean change, between the IG and CG. shows mean differences in the change obtained from the fitted models beta-coefficients of the interaction terms, with standard errors, Bonferroni-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and P-values for the four outcome measures. Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated for reasons of comparability. Patients in the IG showed improvement in the TUG that was 1.5 seconds greater than showed by patients in the CG, which is equivalent to a small to moderate effect, as defined by Cohen.Citation23 Also in the mod Rom tests, a significant relative improvement, of 0.8 seconds, was accomplished compared with CG. For the CST, no significant differences were found between the IG and CG (1.2 seconds difference).

Table 3 Results of the random intercept and random slope model for the short-term effects of the intervention on the secondary outcomes

The overall score of the psychological risk factor – fear of falling – was significantly reduced by 3.7 points in the FES-I questionnaire, in the IG relative to CG.

Mean trajectories in all four considered outcomes of both groups can be viewed in detail in (dotted lines). Box plots represent the distributions of the each of the measures at pretest (T0) and retest (T1).

Figure 2 Change in physical and psychological outcomes before and after the intervention.

Adherence to intervention

In total, 76.6% (N = 170) of the IG participated in more than 75% of the supervised group sessions. Only 2.7% (N = 6) missed the supervised training sessions due to sickness. Of all participants, 55.6% reported that they trained according to the protocol while unsupervised. Of these, 6.6% (N = 15) trained unsupervised between one and five times during the intervention phase, 8.6% (N = 19) trained six to eight times, 24.3% (N = 55) trained nine or ten times, 18% (N = 40) trained eleven times, and 12.6% trained 12 times. No adverse events were reported for the intervention sessions. In three training groups, transportation had to be provided for the participants to take part at each session.

Qualitative data on the intervention by the instructors

After the end of the intervention, each exercise instructor gave feedback about handling the structured intervention with regard to time management in each exercise session (60 minutes), about the structured protocol of the intervention sessions, and his/her experience with the intervention. The structured protocol of the sessions was rated by 80.2% of instructors as understandable and easy to handle. In total, 87.5% rated the time for each session as “just right.” The educational aspects included in each session were rated by ten (62.5%) of the instructors as “just right.” The intensity of the strength, and balance and gait exercise was rated by 13 (81.3%) and 12 (75%), respectively as “just right.” The physical capacities of participants improved according to 87.6% of the exercise instructors.

Out of 15 instructors, six gave positive information on continuing the exercise program for the participants, as well as for new participants.

Discussion

In this paper, we investigated the effects of a 16-week fall-prevention intervention on strength, balance, fear of falling, and function, with a cluster, randomized approach, in the GP office setting. With a new approach for fall prevention, we targeted functionally declined, but still independent, community-dwelling older persons by utilizing the GP setting.

Our positive results are in line with other effective exercise interventions addressing risk for falls in functionally declined older persons.Citation1,Citation7,Citation24–Citation26 By increasing balance and function and decreasing fear of falling, the most important risk factors for falls have been positively influenced in our study population, who are at high risk of falling.Citation27,Citation28

Our intervention showed small to moderate short-term effects on balance (mod Rom), mobility (TUG), and fear of falling (FES-I), but not on strength (CST). Other studies in this population have demonstrated similar results for mobility and balance.Citation7,Citation29–Citation31 One explanation for the lack of positive results in strength might be that the exercise was performed – although in a progressive manner – only with body weights and not additional weights. Another explanation for our data could be the enormous variation in physical performance in the IG and CG and/or the delay of effects of our strength training.

Our study supports the design of complex exercise programs, demonstrating effects on physiological and psychological fall risks and thus addressing physical and behavioral dimensions for fall risks.Citation21 Although complex interventions, which included educational aspects in addition to the exercise components, make it hard to pinpoint the single effects we demonstrated, addressing individual functional levels with exercise variations seemed valuable to foster adherence and motivation in our study population.

The high adherence rate in our IG was also supported by the provision of transportation possibilities that enabled functionally declined older persons to take part in an exercise intervention program (supporting the findings by McMahon et al).Citation32 Our study also demonstrated the feasibility of a combination of supervised and unsupervised sessions in functionally limited, community-dwelling, older persons recruited by their GPs, although we have to admit that information on the unsupervised session was self-reported by the patients, thus to be interpreted with caution. The longitudinal, objective follow-up assessment will give us valuable information on adherence to unsupervised home-based exercise by the participants. The high acceptance and adherence to the structured protocol by the exercise instructors also demonstrates the need for an educational workshop for future instructors, at the start of an intervention. The competence of exercise instructors is essential for the success of the whole study, especially in a multicenter trial, demonstrating the importance of being trained in the underlying concepts and theoretical approaches.

Our strategy to implement a complex fall-prevention exercise program in the GP setting demonstrates the challenges in doing so. In addition to understanding what works, it is necessary to also investigate how implementation in the real world can be achieved. This remains a challenge.Citation33–Citation35 Increased awareness of possible strategies to reduce falls and assessing the risk of falling by GPs seems mandatory for positive effects in fall reduction on a larger scale:Citation8,Citation36 GPs are important in fall prevention management due to the acceptance of their advice by older personsCitation9 and their role in identifying older at-risk persons. In contrast to other studies,Citation12 our study required major efforts to recruit GPs, with an initial response rate of 2%. Although data was not obtained in a structured interview, most GPs declined to participate due to a lack of financial reimbursement and time, or regarded fall prevention as being of little importance. These aspects demonstrate, on the one hand, the need for adequate financial reimbursement if fall prevention strategies are to be implemented successfully in the GP setting and, on the other hand, the ongoing education of GPs with respect to the importance of fall prevention. Nevertheless, our study demonstrated the possibility of implementing fall prevention in the GP setting for older patients. It further supported the need for strategies to raise the awareness in GPs regarding the fall risk in their older patients, eg, educational workshops, familiarization with fall risk assessment, and the importance of a fall definition.Citation4,Citation34,Citation37

Nevertheless, some limitations have to be acknowledged. The recruitment of the GPs depended mostly on personal contacts, thus reaching only the already interested GPs. In addition, structured information about the reasons for not participating was not obtained from the invited GPs or patients. Unfortunately, these data were only obtained in telephone contacts in the recruitment process and not followed further. Also, we obtained no information about whether the educational session changed the usual care routine of the control GPs. To our knowledge, the educational session did raise the awareness of regular fall risk screening in all participating GPs, but we were not able to evaluate, with our study, the possible extent of change in daily GP practice.

Another limitation is that the randomization process of the GPs took place before they started recruiting patients, thus causing a problem with the congruency of every variable, despite clear inclusion criteria. In addition, not all randomized GPs were able to recruit participants or lost interest and therefore dropped out the study. In addition, our study had over 70% female participants, making it hard to generalize our findings to both genders. The last limitation, which has to be mentioned, is the fact that the study was not blinded for the participants, creating a potential bias. However, as has been noted in this paper, it is not possible to solve this problem when comparing an exercise intervention to usual care.

GPs are important persons of trust for older persons, and the advice of GPs is widely recognized.Citation12 The strength of our study lies in the strategy of accessing high-risk older persons for fall prevention through their GPs, with a complex approach targeting the biopsychosocial resources of the participants.

Conclusion

The new strategy to target highly at-risk and functionally declined community-dwelling, older persons for fall prevention via a GP setting seemed promising. Our complex exercise intervention for fall prevention has effectively improved balance, physical function, and led to a reduction in fear of falling in this population. Further research must investigate the process of further maintenance and adherence, as well as the longitudinal effects of the exercise program.

Author contributions

Ellen Freiberger participated in study conceptualization and design, acquisition of subjects and/or data, intervention development, analysis and interpretation of data, and wrote major parts of the manuscript. Wolfgang A Blank participated in study conceptualization and design, acquisition of subjects and/or data, and manuscript preparation. Johannes Salb participated in acquisition of subjects and/or data, and manuscript preparation. Barbara Geilhof participated in acquisition of subjects and/or data, and manuscript preparation. Christian Hentschke participated in analysis and interpretation of data, and he drafted the tables and figures, and prepared the statistical part of the manuscript. Peter Landendörfer participated in study conceptualization and design, and acquisition of subjects and/or data. Martin Halle participated in study conceptualization and design, and manuscript preparation. Monika Siegrist participated in study conceptualization and design, acquisition of subjects and/or data, intervention development, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the Bavarian State Ministry of the Environment and Public Health (Gesund. Leben. Bayern.) (Grant number: LP 00110, Pr Nr 09-10).

We want to thank Liz Woodward for reviewing our paper as a native speaker, and we want to thank all our participants as well as the general practitioners and their staff, for taking part in our study and giving us their time.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GillespieLDRobertsonMCGillespieWJInterventions for preventing falls in older people living in the communityCochrane Database Syst Rev20129CD00714622972103

- TinettiMWilliamsCSFalls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing homeN Engl J Med199733718127912849345078

- KannusPSievänenHPalvanenMJärvinenTParkkariJPrevention of falls and consequent injuries in elderly peopleLancet200536695001885189316310556

- RubensteinLZSolomonDHRothCPDetection and management of falls and instability in vulnerable elders by community physiciansJ Am Geriatr Soc20045291527153115341556

- SattinRWFalls among older persons: a public health perspectiveAnnu Rev Public Health1992134895081599600

- DayLFinchCFHillKDA protocol for evidence-based targeting and evaluation of statewide strategies for preventing falls among community-dwelling older people in Victoria, AustraliaInj Prev2011172e321186224

- SherringtonCTiedemannAFairhallNCloseJCLordSRExercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated meta-analysis and best practice recommendationsN S W Public Health Bull2011223–4788321632004

- GanzDAAlkemaGEWuSIt takes a village to prevent falls: reconceptualizing fall prevention and management for older adultsInj Prev200814426627118676787

- YardleyLDonovan-HallMFrancisKToddCAttitudes and beliefs that predict older people’s intention to undertake strength and balance trainingJ Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci2007622P119P12517379672

- DayLFildesBGordonIFitzharrisMFlamerHLordSRandomised factorial trial of falls prevention among older people living in their own homesBMJ2002325735612812130606

- YardleyLKirbySBen-ShlomoYGilbertRWhiteheadSToddCHow likely are older people to take up different falls prevention activities?Prev Med200847555455818817810

- GardnerMMPhtyMRobertsonMCMcGeeRCampbellAJApplication of a falls prevention program for older people to primary health care practicePrev Med200234554655311969356

- GatesSFisherJDCookeMWCarterYHLambSEMultifactorial assessment and targeted intervention for preventing falls and injuries among older people in community and emergency care settings: systematic review and meta-analysisBMJ2008336763613013318089892

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin (DEGAM)Ältere Sturzpatienten DEGAM Leitlinien Nr. 42004Accessed Dec. 2004 German

- MullerCAKlaassen-MielkeRPennerEJunius-WalkerUHummers-PradierETheileGDisclosure of new health problems and intervention planning using a geriatric assessment in a primary care settingCroat Med J201051649350021162161

- BlankWAFreibergerESiegristMAn interdisciplinary intervention to prevent falls in community-dwelling elderly persons: protocol of a cluster-randomized trial [PreFalls]BMC Geriatr201111721329525

- Shumway-CookABrauerSWoollacottMPredicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go TestPhys Ther20008089690310960937

- GuralnikJFerrucciLPieperCFWallaceRBLower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance batteryJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2000554221M231

- CraigPDieppePMacintyreSMedical Research Council GuidanceDeveloping and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidanceBMJ2008337a165518824488

- FreibergerEMenzHBAbu-OmarKRuttenAPreventing falls in physically active community-dwelling older people: a comparison of two intervention techniquesGerontology200753529830517536207

- FreibergerEHäberleLSpirdusoWWZijlstraGALong-term effects of three multicomponent exercise interventions on physical performance and fall-related psychological outcomes in community-dwelling older adults: a randomized controlled trialJ Am Geriatr Soc201260343744622324753

- BorgGBorg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain ScalesChampaign, IL, USAHuman Kinetics1998

- CohenJStatistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral SciencesHillsdale, NJLawrence Erlbaum Associates1988

- Liu-AmbroseTKhanKMEngJJJanssenPALordSRMcKayHAResistance and agility training reduce fall risk in women aged 75 to 85 with low bone mass: a 6-month randomized, controlled trialJ Am Geriatr Soc200452565766515086643

- Liu-AmbroseTKhanKMEngJJLordSRMcKayHABalance confidence improves with resistance or agility training. Increase is not correlated with objective changes in fall risk and physical abilitiesGerontology200450637338215477698

- AlferiFMRibertoMAbril-CarreresAEffectiveness of an exercise program on postural control in frail older adultsClin Interv Aging2012759359823269865

- ToddCSkeltonDWhat are the Main Risk Factors for Falls Among Older People and What are the Most Effecxtive Interventions to Prevent these Falls?CopenhagenWHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Evidence Network Report)2004 Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/document/e82552.pdfAccessed June 26, 2013

- TinettiMESpeechleyMGinterSFRisk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the communityN Engl J Med198831926170117073205267

- BulatTHart-HughesSAhmedSEffect of a group-based exercise program on balance in elderlyClin Interv Aging20072465566018225467

- FaberMJBosscherRJChinAPawMJvan WieringenPCEffects of exercise programs on falls and mobility in frail and pre-frail older adults: A multicenter randomized controlled trialArch Phys Med Rehabil200687788589616813773

- DeVitoCAMorganRODuqueMAbdel-MotyEVirnigBAPhysical performance effects of low-intensity exercise among clinically defined high-risk eldersGerontology200349314615412679604

- McMahonSTalleyKMWymanJFOlder people’s perspectives on fall risk and fall prevention programs: a literature reviewInt J Older People Nurs20116428929822078019

- GanzDAYanoEMSalibaDShekellePGDesign of a continuous quality improvement program to prevent falls among community-dwelling older adults in an integrated healthcare systemBMC Health Serv Res2009920619917122

- TinettiMEBakerDIKingMEffect of dissemination of evidence in reducing injuries from fallsN Engl J Med2008359325226118635430

- HendriksMRBleijlevensMHvan HaastregtJCLack of effectiveness of a multidisciplinary fall-prevention program in elderly people at risk: a randomized, controlled trialJ Am Geriatr Soc20085681390139718662214

- TinettiMEGordonCSogolowELapinPBradleyEHFall-risk evaluation and management: challenges in adopting geriatric care practicesGerontologist200646671772517169927

- JetteAM“Invention is hard, but dissemination is even harder”Phys Ther200585539039115842187