Abstract

Purpose

Many family caregivers of persons with dementia (PWD) are unable to participate in community center-based caregiver support services because of logistical constraints. This study evaluated the effectiveness of a telephone-delivered psychoeducational intervention for family caregivers of PWD in alleviating caregiver burden and enhancing caregiving self-efficacy.

Subjects and methods

In a single-blinded randomized controlled trial, 38 family caregivers of PWD were randomly allocated into an intervention group or a control group. The intervention group received psychoeducation from a registered social worker over the phone for 12 sessions. Caregivers in the control group were given a DVD containing educational information about dementia caregiving. Outcomes of the intervention were measured by the Chinese versions of the Zarit Burden Interview and the Revised Scale for Caregiving Self-efficacy. Mann–Whitney U tests were used to compare the differences between the intervention and control groups.

Results

The level of burden of caregivers in the intervention group reduced significantly compared with caregivers in the control group. Caregivers in the intervention group also reported significantly more gain in self-efficacy in obtaining respite than the control group.

Conclusion

A structured telephone intervention can benefit dementia caregivers in terms of self-efficacy and caregiving burden. The limitations of the research and recommendations for intervention are discussed.

Introduction

In the Chinese population in Hong Kong, close to 10% of elderly people are at risk of very mild to mild dementia.Citation1 Dementia is not only a disease to the patient; family caregivers of persons with dementia (PWD) are often highly stressed because of their caregiving duties. Stress and burden of caregivers are associated with a number of detrimental outcomes on both the caregiver and PWD, including depression, reduced quality of life, and premature institutionalization of PWD.Citation2–Citation4 Emotional strain also adversely affects the caregivers’ physical health and mortality.Citation5 Increasing concerns have been drawn, thus, to the health and well-being of dementia caregivers in recent years, with ample studies being carried out on the effectiveness of various interventions in reducing the stress and burden of caregivers.Citation6–Citation9

In a meta-analysis examining the overall effectiveness of caregiver interventions, psychoeducational interventions were found to have the most consistent effects on most outcome measures, including caregivers’ knowledge of dementia, well-being, burden, and depressive symptoms.Citation10 Psychoeducation for dementia caregivers involves “structured presentation of information about dementia, expectable caring issues, stress management, and techniques to manage behaviors of PWD,”Citation11 and may include an active role of participants.Citation7 Interventions are typically delivered by a professional worker through lectures, group discussions, and written materials.

Due to its high accessibility and cost-effective implementation,Citation12 a telephone-delivered support service for dementia caregivers has received considerable attention from researchers and caregivers alike in Western countries. Caregivers have expressed positive feedback that telephone interventions and support services fulfilled their needs, as well as preference for telecommunication sessions over the traditional face-to-face support groups.Citation13,Citation14 Moreover, studies have shown that telephone intervention benefited the caregivers in terms of increasing their use of appropriate community services, reducing caregiver burden and depression, and improving caregiving self-efficacy as well as quality of life.Citation8,Citation12,Citation15–Citation18

Telephone intervention has been shown to be effective in delivering psychoeducation to dementia caregivers with various cultural backgrounds.Citation19 In Hong Kong, many caregivers fail to join caregiver support services because of logistical problems. Telephone-delivered interventions can be a viable alternative for providing support for these caregivers who fail to attend traditional face-to-face interventions.Citation17,Citation20

Using a single-blinded randomized controlled trial design, the present study investigates the effectiveness of a telephone-delivered psychoeducational intervention in supporting dementia caregivers in the community. The intervention is based on theories including psychosocial transition and stress coping theory, under the framework of cognitive behavioral therapy,Citation10,Citation12,Citation21 and focuses on providing emotional support; directing caregivers to appropriate resources; encouraging them to attend to their own physical, emotional, and social needs; and educating them on strategies to cope with ongoing problems. It is hypothesized that the telephone-delivered psychoeducational intervention can alleviate caregiver burden and enhance caregiving self-efficacy.

Method

Participants and procedure

Forty-two family caregivers of PWD were recruited through memory clinic and hotline services of a dementia service center between February 2011 and March 2012. Inclusion criteria included (1) care recipients having clinical diagnosis of dementia of any stage, and (2) participants being the primary caregivers of care recipients. Exclusion criteria were caregivers who were under the age of 18 years and those exhibiting intellectual impairment. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion into the study. Ethics approval was obtained from the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong – New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

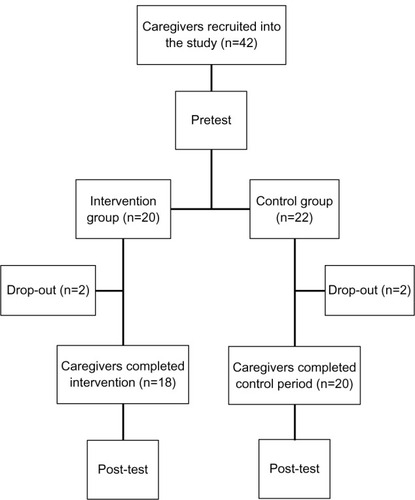

The participants were randomly assigned to either a psychoeducation group (intervention group) or a control group using a computerized randomization program. Both the intervention and the control groups received at the time of pretest a DVD that contained educational information about dementia caregiving. The participants in the intervention group, in addition to the educational DVD, received a 12-session psychoeducation program delivered by registered social workers over the telephone. illustrates the recruitment procedure.

Demographic information and measures on both the participants and care recipients were obtained at pretest prior to group assignment. Pretests were carried out by a research assistant or by self-administration of the caregivers. Post-tests were administered to the participants approximately 3 months after pretest by a research assistant blind to the group assignment of the participants.

Intervention

The psychoeducation intervention program involved 12 sessions of consultation delivered by registered social workers over the telephone (approximately 30 minutes per session, one session per week). The participants in the intervention group were educated and given advice on topics related to dementia caregiving, including knowledge of dementia, skills of communicating with the patient, management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), caregivers’ own emotional issues, resources available in the community, and long-term care plan. The topics covered and the schedule of presentation were similar to typical psychoeducation interventions held “on site” at community centers (). The day and time of phone calls were flexible to the agreement between the participants and the social workers.

Table 1 Topics of intervention

Measures

Basic demographic information about the participants and the care recipients, as well as the clinical parameters of the care recipients (stage of dementia, cognitive functioning, and behavioral problems), were collected as baseline variables. Outcome measures were caregiver burden and caregiving self-efficacy.

Measures on care recipients

Stage of dementia was indexed by the Global Deterioration Scale,Citation22 administered to participants, which categorized the clinical characteristics of dementia patients into seven stages (1 = no cognitive decline, 7 = severe dementia).

Cognitive functioning was assessed by the Abbreviated Mental Test,Citation23 a ten-item screening test for abnormal cognitive function in elders. The Hong Kong Chinese version of the test has been validated locally and a cut-off score of 6 out of 10 had shown a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 94% in a Hong Kong Chinese elderly sample.Citation24 Cronbach’s α of the Chinese version of this instrument was 0.81.Citation25

Behavioral problems of care recipients were measured by the participants using the Chinese version of the Cohen–Mansfeld Agitation Inventory.Citation26,Citation27 The 29-item form measured the frequency of a list of agitated behaviors on a 7-point scale (1 = never, 7 = several times an hour). Cronbach’s α was 0.70 in this sample of care recipients.

Measures on family caregivers

Caregiver burden was measured by the Chinese version of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI).Citation28,Citation29 The ZBI consisted of 22 items pertaining to dementia caregiving in areas of perceived physical and psychological well-being, social life, and finances. The participants indicated, on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = nearly always) during pretest and posttest, how often they experienced distress resulting from caring for a relative with dementia. Cronbach’s α in this sample were 0.81 and 0.85 for pretest and post-test, respectively.

Caregiving self-efficacy was measured by the Chinese version of the Revised Scale for Caregiving Self-efficacy Scale.Citation30,Citation31 The 15-item scale consisted of three subscales (five items per subscale), namely self-efficacy – obtaining respite (SE-OR), self-efficacy – responding to disturbing behaviors (SE-RDB), and self-efficacy – controlling upsetting thoughts (SE-CUT). The participants rated their level of confidence in executing the corresponding tasks of the subscales on a continuous scale from 0% to 100%, according to their recent situation. The average scores of the subscales were reported separately for each domain. Cronbach’s α for SE-OR, SE-RDB, and SE-CUT were 0.90, 0.93, and 0.92, respectively, for pretest, and 0.91, 0.96, and 0.96, respectively, for post-test.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were first calculated. Demographic data and baseline measures on the caregivers and the care recipients were compared between the intervention and the control groups. Outcomes measures (ZBI, Revised Scale for Caregiving Self-efficacy Scale) were analyzed by first calculating the within-group pretest–post-test change scores, and then comparing the change scores between the intervention and the control groups. χ2 tests were used for analyzing categorical data; for ordinal or interval scale data, given the small sample size, Mann–Whitney U tests were used for comparisons between groups.

Results

Forty-two participants were recruited four of them (two from the intervention group and two from the control group) dropped out of the study. The reason for dropout was that they were not approachable for the post-test. All the participants of the intervention group (including the two dropouts) completed the intervention protocol.

The demographic and baseline characteristics of the intervention (n = 18) and the control (n = 20) groups were analyzed using χ2 tests and Mann–Whitney U tests. The results indicated that the two groups were comparable on all demographic variables as well as baseline measures; all P-values were nonsignificant ().

Table 2 Demographic and baseline characteristics of intervention and control groups

Caregiver burden

Pretest, post-test, and change scores on the ZBI of the intervention and the control groups are displayed in . On the whole, the level of caregiver burden reduced from pretest to post-test in the intervention group (median change score −2.50, range −14 to 9), whereas the level of caregiver burden increased in the control group (median change score 3.00, range −22 to 13). Comparison of change scores between the two groups by Mann–Whitney U test revealed a statistically significant reduction in caregiver burden elicited by the intervention, U = 83.0, P < 0.01 (one-tailed), r = 0.46.

Table 3 Pretest scores, post-test scores, and comparison of change score on the Zarit Burden Interview between intervention and control groups

Caregiving self-efficacy

summarizes the pretest, post-test, and change scores on SE-OR, SE-RDB, and SE-CUT SE-OR of the intervention group increased after the program (median change score 3.00, range −44 to 30), whereas the control group had a slight decrease (median change score −0.40, range −32 to 32). Mann–Whitney U test revealed a significant difference between the two groups, U = 123.0, P = 0.05 (one-tailed), r = 0.27. As for SE-RDB, both the intervention and the control groups had an increase (median change score for intervention group 7.50, range −20 to 26, and median change score for control group 3.00, range −18 to 17). Mann–Whitney U test indicated a nonsignificant trend whereby the intervention group showed a larger increase, U = 130.5, P = 0.075 (one-tailed). In respect of SE-CUT, both the intervention and the control groups had a median change score of 0 (range −14 to 22 and −36 to 20, respectively); a nonsignificant difference between groups was observed, U = 169, P = 0.381 (one-tailed).

Table 4 Pretest scores, post-test scores, and comparison of change score on self-efficacy – obtaining respite (SE-OR), self-efficacy – responding to disturbing behaviors (SE-RDB), and self-efficacy – controlling upsetting thoughts (SE-CUT) between intervention and control groups

Discussion

The objective of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of a telephone-delivered psychoeducational intervention in alleviating caregiver burden and enhancing caregiving self-efficacy. It was found that the intervention protocol managed to significantly reduce the caregiving burden, as well as improve the caregivers’ self-efficacy in obtaining respite. A marginal significance in improving the caregivers’ self-efficacy in responding to disruptive behavior was also observed. The high participation rate of the intervention group revealed the high acceptance of this intervention and the need from caregivers who were restricted from receiving in-person support. The caregiving burden of caregivers of PWD was largely related to the constant caring, due to the deterioration of functional capacity of PWD;Citation32 caregivers needed to invest a great deal of time and effort in the caregiving task. By helping the caregivers enhance their self-efficacy, particularly in the aspect of rest-seeking (SE-OR in this study), their caregiver burden could be alleviated.

Intervention in respect of caregivers could be divided into two main aspects, namely those targeted to reducing the amount of caregiving, and those targeted to improving caregiving skills.Citation10 The intervention of this study blended the two aspects. Knowledge related to dementia and dementia care, especially BPSD management, was comprehensively delivered to the participants, according to the capability as well as the individual needs of the participants. Caregiving skills (eg, in terms of communication with PWD) were discussed too, which was anticipated to help the participants perform their caregiving tasks more effectively, thus enhancing their self-efficacy in obtaining respite as well as reducing their caregiving burden.

The improvement in self-efficacy and reduction in caregiving burden might also be attributed to the emotional support in the intervention. Caregivers experienced both burden and satisfaction in their caregiving experience.Citation33 Acknowledging the participants’ burden and worries and developing customized coping strategies, which was the focus in the emotional support sessions of the intervention, might have inspired the participants to search for their internal satisfaction and gain from their caregiving task, thus achieving the positive result of this research.

In this study, an improvement in the participants’ self-efficacy in terms of responding to disturbing behaviors was observed in the intervention group, although the result was not statistically significant. The positive outcome was likely to be attributed to the knowledge related to dementia care delivered in the intervention; caregivers might have overestimated patients’ ability, due to lack of knowledge,Citation11 which, in turn, adversely affected their belief in caregiving tasks. Delivering comprehensive dementia care knowledge and discussing customized BPSD management with the participants would then help them develop better belief in handling the disruptive behavior of PWD. The marginal significance of the improvement observed in this study was likely due to the small sample size. In addition, effectiveness of achieving treatment goals was associated with both intervention method and length of intervention,Citation10 implying that a longer or more intensive intervention period might yield a more significant result in this aspect.

In this study, no difference in self-efficacy in terms of controlling upsetting thoughts was observed. It has been suggested that three elements, namely better caregiver mental health, positive caregiving strategies, and promoting caregiver training and support programs, would help boost caregiver gain.Citation34 The intervention of this study had covered all three elements, and the research results demonstrated the effectiveness of the intervention on the latter two elements. More emphasis on the former one might further help caregivers control their upsetting thoughts related to caregiving.

One limitation of this study was that the degree of effectiveness of the intervention on to caregivers of PWD of different dementia stages was not investigated, due to the relatively small sample size. It was believed that caregivers of PWD of different dementia stages would have different needs, thus different coping strategies, as they would encounter different challenges. Further research with a larger sample size could be implemented to better design intervention models for caregivers of PWD of different dementia stages.

In addition, postintervention effect was not investigated in this study. A meta-analysis pointed out that multicomponent intervention achieved effective results in enhancing caregivers’ well-being in the short term.Citation10 Although the results of this study are in line with the results from the meta-analysis, further research should also investigate the postintervention effect for better evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention as well as determining an optimal time line for the boosting intervention.

One limitation about the intervention was the difficulty in fixing a mutually convenient time for intervention. Many caregivers in Hong Kong were relatively available for intervention during the night-time or at weekends, but on the other hand the social workers who offered the intervention often worked during the daytime and therefore there might be difficulty fixing a mutually convenient intervention time with caregivers. If the intervention was to be arranged at night-time at the convenience of caregivers, it might, in turn, increase the workload of professionals.

Length of intervention was a moderating variable for effective intervention, in that a longer intervention period might benefit the caregivers more.Citation10 This study demonstrated that a 12-session intervention (average total intervention time spent being 6 hours) could help caregivers reduce caregiving burden and increase caregivers’ self-efficacy. However, whether it would be more cost-effective than face-to-face intervention would need further investigation. The outcome of this research served as a direction for intervention outcome; further research with randomized design should be launched for comparing different intervention lengths and confirming an optimal and cost-effective session design so that this mixed intervention model could be effectively carried out to the community caregivers.

This study demonstrates that an intervention mixing practical psychoeducation, caregiving skills teaching, and emotional support, delivered by telephone, would help enhance the participants’ self-efficacy in obtaining respite as well as reduce their caregiving burden. The intervention also offers flexibility in terms of location to the caregivers of PWD, who are very often occupied by their caregiving tasks and cannot spare time for intervention. In addition, dementia is still a stigma in Chinese society;Citation35 caregivers may be hesitant to receive proper intervention. An intervention delivered by telephone thus may fill this service gap in offering an intervention with which the caregivers may culturally feel comfortable.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LamLCTamCWLuiVWPrevalence of very mild and mild dementia in community-dwelling older Chinese people in Hong KongInt Psychogeriatr200820113514817892609

- AneshenselCSPearlinLIMullanJTZaritSHWhitlatchCJProfiles in caregiving: the unexpected careerNew York, USAAcademic Press1995

- PapastavrouEKalokerinouAPapacostasSSTsangariHSourtziPCaring for a relative with dementia: family caregiver burdenJ Adv Nurs200758544645717442030

- YaffeKFoxPNewcomerRPatient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementiaJAMA2002287162090209711966383

- SchulzRBeachSRCaregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects studyJAMA1999282232215221910605972

- AuALiSLeeKThe Coping with Caregiving Group Program for Chinese caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease in Hong KongPatient Educ Couns201078225626019619974

- BourgeoisMSchulzRBurgioLBeachSSkills training for spouses of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: outcomes of an intervention studyJ Clin Geropsychol2002815373

- CoyneACPotenzaMNoseMABCaregiving and dementia: the impact of telephone helpline servicesAm J Alzheimers Dis19951042732

- SchulzRO’BrienACzajaSDementia caregiver intervention research: in search of clinical significanceGerontologist200242558960212351794

- SörensenSPinquartMDubersteinPHow effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysisGerontologist200242335637212040138

- SörensenSDubersteinPGillDPinquartMDementia care: mental health effects, intervention strategies, and clinical implicationsLancet Neurol200651196197317052663

- TremontGDavisJDBishopDSFortinskyRHTelephone-delivered psychosocial intervention reduces burden in dementia caregiversDementia20087450352020228893

- ColantonioAKositskyAJCohenCVernichLWhat support do caregivers of elderly want? Results from the Canadian Study of Health and AgingCan J Public Health200192537637911702494

- PloegJBiehlerLWillisonKHutchisonBBlytheJPerceived support needs of family caregivers and implications for a telephone support serviceCan J Nurs Res2001332436111928335

- BormannJWarrenKARegalbutoLA spiritually based caregiver intervention with telephone delivery for family caregivers of veterans with dementiaFam Community Health200932434535319752637

- FinkelSCzajaSJSchulzRMartinovichZHarrisCPezzutoDE-care: a telecommunications technology intervention for family caregivers of dementia patientsAm J Geriat Psychiat2007155443448

- GlueckaufRLSharmaDJeffersSBTelephone-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for distressed rural dementia caregiversClin Gerontologist20073112141

- WinterLGitlinLNEvaluation of a telephone-based support group intervention for female caregivers of community-dwelling individuals with dementiaAm J Alzheimers Dis2006216391397

- BankALArguellesSRubertMEisdorferCCzajaSJThe value of telephone support groups among ethnically diverse caregivers of persons with dementiaGerontologist200646113413816452294

- Martindale-AdamsJNicholsLOBurnsRMaloneCTelephone support groups: a lifeline for isolated Alzheimer’s disease caregiversAlzheimers Care Today200232181189

- SalfiJPloegJBlackMESeeking to understand telephone support for dementia caregiversWestern J Nurs Res2005276701721

- ReisbergBFerrisSHde LeonMJCrookTThe Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementiaAm J Psychiat19821399113611397114305

- HodkinsonHMEvaluation of a mental test score for assessment of mental impairment in the elderlyAge Ageing1972142332384669880

- ChuLWPeiCKWHoMHChanPTValidation of the Abbreviated Mental Test (Hong Kong version) in the elderly medical patientHong Kong Med J199513207211

- LamSCWongYYWooJReliability and validity of the Abbreviated Mental Test (Hong Kong version) in residential care homesJ Am Geriatr Soc201058112255225721054326

- Cohen-MansfieldJMarxMSRosenthalASA description of agitation in a nursing homeJ Gerontol1989443M77M842715584

- LaiCKYThe use of the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory in the assessment of agitation in people with dementia: applicability in Hong KongHong Kong J Gerontol2002141&26669

- ChanTSFLamLCWChiuHFKValidation of the Chinese version of the Zarit Burden InterviewHong Kong J Psychiatry200515913

- ZaritSHReeverKEBach-PetersonJRelatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burdenGerontologist19802066496557203086

- AuALaiMKLauKMSocial support and well-being in dementia family caregivers: the mediating role of self-efficacyAging Ment Health200913576176819882415

- SteffenAMMcKibbinCZeissAMGallagher-ThompsonDBanduraAThe revised scale for caregiving self-efficacy: reliability and validity studiesJ Gerontol B-Psychol2002571P74P86

- MotenkoAKThe frustrations, gratifications, and well-being of dementia caregiversGerontologist19892921661722753378

- AndrénSElmståhlSFamily caregivers’ subjective experiences of satisfaction in dementia care: aspects of burden, subjective health and sense of coherenceScand J Caring Sci200519215716815877641

- LiewTMLuoNNgWYChionhHLGohJYapPPredicting gains in dementia caregivingDement Geriatr Cogn2010292115122

- ChengSTLamLCChanLCThe effects of exposure to scenarios about dementia on stigma and attitudes toward dementia care in a Chinese communityInt Psychogeriatr201123091433144121729424