Abstract

Aim

Functional capacity and dependency in activities of daily living (ADL) could be important mediators for an association between physical exercise and mental health. The aim of this study was to investigate whether a change in functional capacity or dependency in ADL is associated with a change in depressive symptoms and psychological well-being among older people living in residential care facilities, and whether dementia can be a moderating factor for this association.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was undertaken. Participants were 206 older people, dependent in ADL, living in residential care facilities, 115 (56%) of whom had diagnosed dementia. Multivariate linear regression, with comprehensive adjustment for potential confounders, was used to investigate associations between differences over 3 months in Berg Balance Scale (BBS) and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) scores, and in BBS and Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale (PGCMS) scores. Associations were also investigated between differences in Barthel ADL Index and GDS-15 scores, and in Barthel ADL Index and PGCMS scores.

Results

There were no significant associations between changes in scores over 3 months; the unstandardized β for associations between BBS and GDS-15 was 0.026 (P=0.31), BBS and PGCMS 0.045 (P=0.14), Barthel ADL Index and GDS-15 0.123 (P=0.06), and Barthel ADL Index and PGCMS −0.013 (P=0.86). There were no interaction effects for dementia.

Conclusion

A change in functional capacity or dependency in ADL does not appear to be associated with a change in depressive symptoms or psychological well-being among older people living in residential care facilities. These results may offer one possible explanation as to why studies of physical exercise to influence these aspects of mental health have not shown effects in this group of older people.

Introduction

Depression is the third leading cause of burden of disease, and is an important public health issue since it is associated with suffering for the individual, disability, increased mortality, and poorer outcomes from physical illness.Citation1 Depression and depressive symptoms are also closely associated with decreased psychological well-being, which in turn is associated with loneliness, impaired mobility, and dependency in activities of daily living (ADL) among older people.Citation2 Both depression and decreased psychological well-being are common among older people living in residential care facilities.Citation2–Citation4 In addition, a large proportion of people living in residential care facilities have dementia, and depression has been shown to be even more common in this group.Citation5 The effects of drug treatment for depression among older people seem limited,Citation3,Citation6 especially among people living in residential care facilitiesCitation7 and among people with dementia,Citation8 thus emphasizing the importance of finding alternative ways of treatment.Citation9

Physical exercise of moderate or high intensity seems to have a positive influence on depression and psychological well-being among community-dwelling older people.Citation10–Citation13 Both physiological and psychosocial mechanisms have been proposed for how exercise influences mental health.Citation10,Citation11,Citation14 However, to our knowledge, no randomized controlled intervention study evaluating exercise as a single intervention, using at least moderate intensity or progressively increased load or dose, has shown positive effects on these aspects of mental health among people living in residential care facilities.Citation15–Citation18 The lack of effects on mental health in these studies may be due to a lack of effect or an insufficient amount of effect on functional capacity (what a person is able to perform in a test situation regarding daily physical activities) or on dependency in ADL (the assistance a person actually receives, ie, disability).Citation19 These factors may be important mediators for a relationship between physical exercise and mental health. Increased functional capacity and independence in ADL may be important for mental health through factors such as improved sense of control, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and ability to participate in social activities, or by enhancing an increase of the level of daily physical activity.Citation10,Citation11,Citation20–Citation23 However, people with dementia often have difficulties initiating physical activities,Citation24 and this may moderate the effect of functional capacity and dependency in ADL on mental health.

Another theoretical cause for lack of positive exercise effects on mental health in older people in residential care facilities may be that functional capacity and independence in ADL are not important as mediating factors in this group. A number of longitudinal studies support the association between functional capacity or dependency in ADL and mental health among community-dwelling older people.Citation21,Citation25,Citation26 However, there is lack of studies investigating this association among people living in residential care facilities, including people with dependency in ADL and cognitive impairments. To better understand how two variables interact, an analytic approach for longitudinal data that model changes over time has been called for.Citation25 Thus, investigation of the association between changes in functional capacity or dependency in ADL and changes in mental health will increase the understanding of how physical exercise may influence mental health through improvement of functional capacity or decreased dependency in ADL. The aim of this study was to investigate whether a change in functional capacity or dependency in ADL is associated with a change in depressive symptoms and psychological well-being, among older people living in residential care facilities. A second aim was to investigate whether dementia can be a moderating factor with regard to these associations.

Methods

Participants and setting

Inclusion criteria were living in a residential care facility, aged 65 years and over, dependent on assistance in personal ADL according to the Katz Index of Independence in ADL,Citation27 a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 10 or more,Citation28 being able to rise from a chair with armrests with help from no more than one person, and the approval of the resident’s physician. Residents, and their relatives when appropriate due to cognitive impairment, gave their informed consent after having received oral and written information about the study. The facilities comprised private apartments, with access to a common dining room, alarms, and on-site nursing and care. Some facilities also had specialized units for people with dementia, offering private rooms and staff on hand.

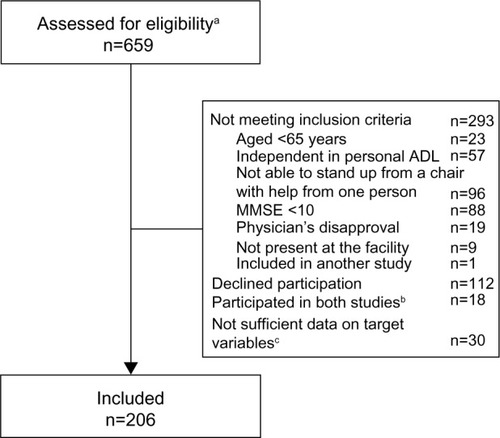

This prospective cohort study was based on data from two studies; the Frail Older People – Activity and Nutrition Study in Umeå (FOPANU study)Citation16,Citation29 and the Residential care facilities – Mobility, Activity, and Nutrition Study in Umeå (REMANU study).Citation30 Baseline assessments and follow-up assessments after 3 months were used, which were performed according to the same procedure and using the same assessment methods in both studies. A number of individuals (n=18) participated in both the FOPANU study and the REMANU study. For those individuals, only data from the FOPANU study were used. Participants with sufficient data on target variables were included in the present study (n=206, ). The participants from the FOPANU study (n=170) were randomized to a high-intensity functional exercise program (n=79) or activities performed while sitting (n=91), held 2–3 times per week for 13 weeks.Citation29 The exercises were based on tasks common in everyday life such as squats, step-ups, and walking over obstacles. The activities while sitting included, for example, conversation, singing, and watching films. The participants from the REMANU study (n=36) received usual care, and the purpose of the study was to monitor changes over time in mobility, activity, and nutrition among older people living in residential care facilities. The studies were approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Umeå (§391/01 and §439/03).

Figure 1 Flowchart of the participants.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination.

Target variables

Functional capacity was assessed using the Berg Balance Scale (BBS) (scores range 0–56), which is a well-established and valid scale to assess functional balance capacity among older people.Citation30,Citation31 The performance of 14 functional balance tasks, most of them common in everyday life, was assessed. Dependency in ADL was assessed using the Barthel ADL Index (scores range 0–20) after interviewing a licensed practical nurse or nurse’s aide who knew the participant well. The Barthel ADL Index is a well-established and valid scale for assessing dependency in care and mobility among older people, and it measures what a person actually does rather than what that person is able to do.Citation32 Mental health was evaluated by assessing symptoms of depression and psychological well-being. The Geriatric Depression Scale 15-item version (GDS-15) (scores range 0–15) was used to assess depressive symptoms.Citation33 The scale was developed for use among older people and is well established and validated for use among people in residential care facilities, including people with cognitive impairments.Citation34,Citation35 Psychological well-being was evaluated using the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale (PGCMS) (scores range 0–17). The PGCMS has been recommended for use among older people to assess their subjective well-being.Citation36 The PGCMS has also been validated against a psychologist’s rating of life satisfaction among older people.Citation37 Both the GDS-15 and the PGCMS comprise questions in a yes/no format and were administered in an interview setting in the present study in order to facilitate completion by people with cognitive decline or functional impairments. Assessments of target variables were performed by trained physical therapists.

Descriptive assessments

The resident’s registered nurse recorded diagnoses, clinical characteristics, and prescribed drugs from medical records and all other available documentation. A specialist in geriatric medicine evaluated the documentation of diagnoses, drug treatment, assessments, and measurements for completion of the final diagnoses at baseline. Depression and dementia were diagnosed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition criteria.Citation38 Visual impairment was defined as the inability to read, with or without glasses, a word written in 5 mm capital letters, at reading distance. Hearing was regarded as impaired when the participant was unable to hear a conversation at normal voice level at a distance of 1 m, or used a hearing aid. Indoor falls during the past 6 months were recorded (yes/no) by interviewing a licensed practical nurse or nurse’s aide who knew the participant well. Cognitive function was assessed using the MMSE scale (scores range 0–30).Citation28 Nutritional status was assessed by a dietician using the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) scale (scores range 0–30).Citation39 Self-perceived health was assessed using item P from the MNA.

Statistical analyses

Difference in the target variables was calculated as the 3-month follow-up value minus the baseline value. Linear regression was used to investigate associations between differences in BBS and GDS-15 scores and BBS and PGCMS scores, respectively. Likewise, associations were investigated between differences in the Barthel ADL Index and GDS-15 scores, and in the Barthel ADL Index and PGCMS scores, respectively. Participants with data on differences in GDS-15 or PGCMS scores and differences in the BBS or Barthel ADL Index scores formed the sample for each separate analysis. The dependent variable was either difference in GDS-15 or difference in PGCMS. Independent variables were difference in BBS or Barthel ADL Index. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses were performed. The multivariate linear regression was adjusted (by adding independent variables) for age, sex, and baseline characteristics () with univari ate associations to the dependent variable (P≤0.15), and evaluated in each sample (). Independent gait was not included in the multivariate regression when analyzing associations between Barthel ADL Index and PGCMS because it is a part of the Barthel ADL Index scale. Interaction analysis was performed to investigate the moderating effects of dementia. The multivariate analyses were tested for interaction by including dementia and the product of dementia and the difference in BBS or Barthel ADL Index, respectively, as independent variables in each multivariate model. Additional interaction analyses were performed for sex, baseline level of functional balance capacity (BBS score dichotomized on the median value, BBS =31) or dependency in ADL (Barthel ADL Index score dichotomized on the median value, Barthel ADL Index =15), and activity (exercise, activity, or usual care). The rationale for investigating the interaction effects of activity was that it may be important for the association with mental health, whether improved functional capacity or decreased dependency in ADL results from the effects of physical exercise or from factors such as recovery from a disease. Analyses were performed using the SPSS software version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) with P-values of <0.05 considered to indicate statistical significance.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the participants

Table 2 Baseline values and differences for the following target variables: Berg Balance Scale, Barthel ADL Index, Geriatric Depression Scale, and Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale

Table 3 Univariate and multivariate linear regression for associations between differences in BBS and GDS-15, or PGCMS, respectively, as well as between differences in Barthel ADL Index and GDS-15, or PGCMS, respectively. Each analysis in the multivariate model was evaluated for interaction of dementia disorder

Results

A total of 206 people were included in the study. A description of the participants’ baseline characteristics is shown in . The mean age was 84.3 years, 153 (74%) participants were women, and 122 (59%) had a diagnosis of depression; 101 (49%) participants were receiving antidepressants at baseline. At 3-month follow-up, four (2%) participants had discontinued the use of antidepressants and five (2.5%) participants had started using antidepressants. A total of 115 (56%) participants had a diagnosed dementia. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) MMSE score was 18.0±5.2.

Baseline values and differences in target variables are displayed in . The absolute differences in mean ± SD (range) between follow-up and baseline were BBS 4.7±4.1 (0–21), Barthel ADL Index 1.7±1.8 (0–12), GDS-15 1.6±1.5 (0–7), and PGCMS 1.8±1.8 (0–12).

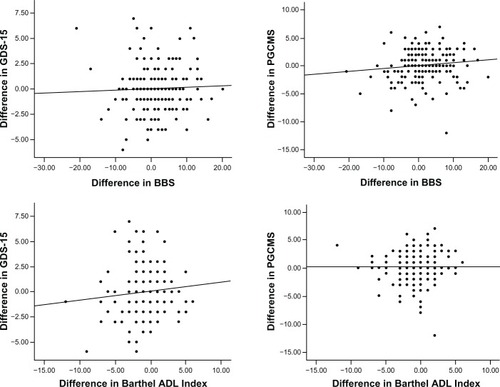

Scatterplots of the distribution of differences in target variables are shown in . There were no significant associations in the univariate or the multivariate linear regression analyses. In the multivariate model, the unstandardized β between changes in scores over 3 months in BBS and GDS-15 was 0.026 (P=0.31), in BBS and PGCMS 0.045 (P=0.14), in Barthel ADL Index and GDS-15 0.123 (P=0.06), and in Barthel ADL Index and PGCMS −0.013 (P=0.86) (). There was a significant interaction effect of baseline level of functional capacity between changes in BBS and GDS (P=0.03). Additional multivariate regression analyses between changes in BBS and GDS scores showed unstandardized β 0.064 (P=0.06) among people with BBS <31, and −0.046 (P=0.26) among people with BBS ≥31. There were no other interaction effects for the subgroups of dementia (), sex, activity group, and level of functional capacity or dependency in ADL at baseline (data not shown).

Figure 2 Scatterplots of the differences in scores (follow-up value minus baseline values) in BBS versus GDS-15 (r2=0.001, P=0.63) and PGCMS (r2=0.02, P=0.09), respectively, and likewise, difference in Barthel ADL Index versus GDS-15 (r2=0.009, P=0.18) and PGCMS (r2<0.001, P=0.97), respectively. For all assessment scales except the GDS-15, a positive difference indicates improved function or mental health from baseline to follow-up. A single dot can represent one or more individuals.

Discussion

The present study showed no significant associations between change in functional capacity or dependency in ADL, and change in depressive symptoms or psychological well-being among older people living in residential care facilities. A significant interaction effect indicated a difference in the association between changes in functional capacity and depressive symptoms depending on the level of functional capacity at baseline. However, when associations between the variables among people with high and low levels of functional capacity was investigated separately, the β-levels were low and non-significant, suggesting limited clinical relevance of the interaction. Further, no other interaction analyses showed any moderating effects for dementia, sex, whether or not an activity was offered during the 3-month follow-up period, or for baseline level of functional capacity or dependency in ADL.

In contrast with the present study, earlier prospective studies among community-dwelling older people have found that changes in functional capacity or dependency in ADL are associated with change in depression.Citation21,Citation22,Citation40 In addition, a qualitative study of community-dwelling older informants described the importance of independence in mobility and ADL for life satisfaction.Citation23 However, these associations may not be applicable to people living in residential care facilities. Several explanations may be proposed for the lack of associations in this group. First, people living in this type of setting are all highly disabled and, although they would improve their functional capacity or decrease their dependency in ADL, they are still likely to be dependent on assistance in ADL. Thus, changes in functional capacity or dependency in ADL in this group may have limited impact on, for example, self-esteem or sense of control, which have been shown to be important mediators for a relationship between disability and depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older people.Citation11,Citation22 Second, since these people are dependent in ADL, changes in functional capacity or dependency in ADL may not influence mental health because the perceptions of quality of life among these people may have changed, ie, through a response shift.Citation41 Third, older people in residential care facilities often suffer from multimorbidity and organic brain disorders such as dementia or stroke. Treatment of depression seems to have limited effects in this group and may be explained by differences in the etiology of depression compared with older people without multimorbidity and organic brain disorders.Citation3,Citation5,Citation6,Citation8,Citation16,Citation42 The difference in etiology may also explain why there were no associations between changes in functional capacity or dependency in ADL and mental health. Fourth, increased functional capacity and decreased dependency in ADL may not lead to increased daily physical activity in this group, and thus, have an impact on mental health.Citation20 Increasing the level of daily physical activity may be challenging for this group.Citation43 Unfortunately, in the present study, the daily physical activity level of the participants was not measured due to limited resources.

Physical exercise programs have shown positive effects on functional capacity and ADL ability among people living in residential care facilities,Citation44 including people with dementia.Citation45 The present study indicates that functional capacity and dependency in ADL do not seem to mediate an association between physical exercise and mental health. These results may offer one possible explanation as to why studies of exercise as a single intervention to influence mental health, performed 2–3 times per week, have not shown effects in this group of older people.Citation15–Citation18 Future studies may focus on evaluating exercise offered with higher frequency (more than three sessions per week), or with the aim of increasing the levels of daily physical activity to better influence mental health, through physiological (eg, endorphins or monoamine levels) or psychosocial effects (eg, self-efficacy or social stimulation). Further, it may be of importance that the exercise is performed with moderate or high intensity since one of the earlier studies,Citation16 evaluating exercise with higher intensity than the other studies, revealed a positive effect on well-being in a sub-group of people with dementia.

A methodological strength in the present study is the use of changes over time to analyze the associations of two variables, instead of analyzing the association by using a level of a variable at baseline to predict a level of another variable at follow-up. Neither of these two analytic approaches makes it possible to draw any conclusions about the causal relationship between the variables. However, the analyses in the present study provide a better understanding of how functional capacity and dependency in ADL interact with mental health over time among older people living in residential care facilities. Further, comprehensive assessments made it possible to adjust the analyses for many potential confounders. Some limitations in external validity exist since people with MMSE scores below 10, and people not able to rise from a chair despite help from one person, were excluded. However, all participants were dependent in ADL, and the study included people with dementia and cognitive impairment, who make up a large part of those living in residential care facilities.

Another limitation in this study concerns the absolute reliability of the target variables. In the population studied, it is likely that many individuals have a fluctuating health status due to a high prevalence of diseases and physical and cognitive impairments, and this may contribute to variability in measurements and make it more difficult to reveal associations between rating scales. The BBS (scores range 0–56) has been investigated for absolute reliability in this population of older people in residential care facilities and the results showed that a change of 8 BBS points (95% confidence interval) is required in order to establish a genuine change in function in this group.Citation30 To our knowledge, absolute reliability has not been investigated for the other rating scales in the present study. A total of 43 individuals in the present study had a difference in BBS scores of 8 or more. There is no visible association between differences in BBS scores and differences in GDS-15 or PGCMS scores, respectively, among these individuals (). This lack of association strengthens the conclusion that no association exists between functional capacity or dependency in ADL and mental health in this group of older people. Furthermore, the β-values for the investigated associations were small.

Conclusion

A change in functional capacity or dependency in ADL does not appear to be associated with a change in depressive symptoms or psychological well-being among older people living in residential care facilities, including people with dementia. These results may offer one possible explanation as to why studies of physical exercise to influence these aspects of mental health have not shown effects in this group of older people.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council K2009-69P-21298-01-4, K2009-69X-21299-01-1, and K2009-69P-21298-04-4; the King Gustaf V’s and Queen Victoria’s Foundation of Freemasons; the County Council of Västerbotten (ALF); the Swedish Dementia Foundation; the Alzheimer Foundation; and Erik and Anne-Marie Detlof’s Foundation at Umeå University.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BlazerDG2ndHybelsCFOrigins of depression in later lifePsychol Med20053591241125216168147

- von HeidekenWågert PRönnmarkBRosendahlEMorale in the oldest old: the Umeå 85+ studyAge Ageing200534324925515784647

- BergdahlEGustavssonJMKallinKDepression among the oldest old: the Umeå 85+ studyInt Psychogeriatr200517455757516185377

- LevinCAWeiWAkincigilALucasJABilderSCrystalSPrevalence and treatment of diagnosed depression among elderly nursing home residents in OhioJ Am Med Dir Assoc20078958559417998115

- BergdahlEAllardPGustafsonYDepression among the very old with dementiaInt Psychogeriatr201123575676321205392

- WilkinsonPIzmethZContinuation and maintenance treatments for depression in older peopleCochrane Database Syst Rev201211CD00672723152240

- BoyceRDHanlonJTKarpJFKlokeJSalehAHandlerSMA review of the effectiveness of antidepressant medications for depressed nursing home residentsJ Am Med Dir Assoc201213432633122019084

- BanerjeeSHellierJDeweyMSertraline or mirtazapine for depression in dementia (HTA-SADD): a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet2011378978940341121764118

- WilkinsVMKiossesDRavdinLDLate-life depression with comorbid cognitive impairment and disability: nonpharmacological interventionsClin Interv Aging2010532333121228897

- NetzYWuMJBeckerBJTenenbaumGPhysical activity and psychological well-being in advanced age: a meta-analysis of intervention studiesPsychol Aging200520227228416029091

- RimerJDwanKLawlorDAExercise for depressionCochrane Database Syst Rev20127CD00436622786489

- SinghNAStavrinosTMScarbekYGalambosGLiberCFiatarone SinghMAA randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adultsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200560676877615983181

- SjöstenNKiveläSLThe effects of physical exercise on depressive symptoms among the aged: a systematic reviewInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200621541041816676285

- ErnstCOlsonAKPinelJPLamRWChristieBRAntidepressant effects of exercise: evidence for an adult-neurogenesis hypothesis?J Psychiatry Neurosci2006312849216575423

- ChinAPawMJvan PoppelMNTwiskJWvan MechelenWEffects of resistance and all-round, functional training on quality of life, vitality and depression of older adults living in long-term care facilities: a ‘randomized’ controlled trialBMC Geriatr20044515233841

- ConradssonMLittbrandHLindelöfNGustafsonYRosendahlEEffects of a high-intensity functional exercise programme on depressive symptoms and psychological well-being among older people living in residential care facilities: a cluster-randomized controlled trialAging Ment Health201014556557620496181

- MorrisJNFiataroneMKielyDKNursing rehabilitation and exercise strategies in the nursing homeJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci19995410M494M50010568531

- RollandYPillardFKlapouszczakAExercise program for nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease: a 1-year randomized, controlled trialJ Am Geriatr Soc200755215816517302650

- JetteAMDisablement outcomes in geriatric rehabilitationMed Care199735Suppl 6JS28JS37 discussion JS38–JS449191712

- LeeYParkKDoes physical activity moderate the association between depressive symptoms and disability in older adults?Int J Geriatr Psychiatry200823324925617621384

- LenzeEJRogersJCMartireLMThe association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability: a review of the literature and prospectus for future researchAm J Geriatr Psychiatry20019211313511316616

- YangYHow does functional disability affect depressive symptoms in late life? The role of perceived social support and psychological resourcesJ Health Soc Behav200647435537217240925

- ÅbergACSidenvallBHepworthMO’ReillyKLithellHOn loss of activity and independence, adaptation improves life satisfaction in old age–a qualitative study of patients’ perceptionsQual Life Res20051441111112516041906

- PerrinTOccupational need in severe dementia: a descriptive studyJ Adv Nurs19972559349419147198

- BruceMLDepression and disability in late life: directions for future researchAm J Geriatr Psychiatry20019210211211316615

- SchillerstromJERoyallDRPalmerRFDepression, disability and intermediate pathways: a review of longitudinal studies in eldersJ Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol200821318319718838741

- KatzSFordABMoskowitzRWJacksonBAJaffeMWStudies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial functionJAMA196318591491914044222

- TombaughTNMcIntyreNJThe mini-mental state examination: a comprehensive reviewJ Am Geriatr Soc19924099229351512391

- RosendahlELindelöfNLittbrandHHigh-intensity functional exercise program and protein-enriched energy supplement for older persons dependent in activities of daily living: a randomised controlled trialAust J Physiother200652210511316764547

- ConradssonMLundin-OlssonLLindelöfNBerg balance scale: intrarater test-retest reliability among older people dependent in activities of daily living and living in residential care facilitiesPhys Ther20078791155116317636155

- BergKOWood-DauphineeSLWilliamsJIMakiBMeasuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrumentCan J Public Health199283Suppl 2S7S111468055

- CollinCWadeDTDaviesSHorneVThe Barthel ADL Index: a reliability studyInt Disabil Stud198810261633403500

- SheikhJIYesavageJAGeriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter versionClin Gerontol198651–2165172

- ConradssonMRosendahlELittbrandHGustafsonYOlofssonBLövheimHUsefulness of the Geriatric Depression Scale 15-item version among very old people with and without cognitive impairmentAging Ment Health201317563864523339600

- JongenelisKPotAMEissesAMDiagnostic accuracy of the original 30-item and shortened versions of the Geriatric Depression Scale in nursing home patientsInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200520111067107416250079

- Royal College of Physicians of London, British Geriatrics SocietyStandardized assessment scales for elderly people A report of joint workshops in the Research Unit of the Royal College of Physicians of London and the British Geriatrics SocietyLondonThe Royal College of Physicians of London and the British Geriatrics Society1992

- LawtonMThe dimensions of moraleKentDPKastenbaumRSherwoodSResearch Planning and Action for the Elderly: the Power and Potential of Social ScienceNew YorkBehavoural Publications1972

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th edWashington DCAmerican Psychiatric Association1994

- GuigozYVellasBGarryPJMini Nutritional Assessment: a practical assessment tool for grading the nutritional state of elderly patientsNutr Facts Res Gerontol199441559

- SchiemanSPlickertGFunctional limitations and changes in levels of depression among older adults: a multiple-hierarchy stratification perspectiveJ Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci2007621S36S4217284565

- SprangersMASchwartzCEIntegrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical modelSoc Sci Med199948111507151510400253

- TaylorWDAizensteinHJAlexopoulosGSThe vascular depression hypothesis: mechanisms linking vascular disease with depressionMol Psychiatry201318996397423439482

- ChinAPawMJvan PoppelMNvan MechelenWEffects of resistance and functional-skills training on habitual activity and constipation among older adults living in long-term care facilities: a randomized controlled trialBMC Geriatr20066916875507

- ValenzuelaTEfficacy of progressive resistance training interventions in older adults in nursing homes: a systematic reviewJ Am Med Dir Assoc201213541842822169509

- LittbrandHStenvallMRosendahlEApplicability and effects of physical exercise on physical and cognitive functions and activities of daily living among people with dementia: a systematic reviewAm J Phys Med Rehabil201190649551821430516