?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Background

Injury due to falls is a major problem among older adults. Decrements in dual-task postural control performance (simultaneously performing two tasks, at least one of which requires postural control) have been associated with an increased risk of falling. Evidence-based interventions that can be used in clinical or community settings to improve dual-task postural control may help to reduce this risk.

Purpose

The aims of this systematic review are: 1) to identify clinical or community-based interventions that improved dual-task postural control among older adults; and 2) to identify the key elements of those interventions.

Data sources

Studies were obtained from a search conducted through October 2013 of the following electronic databases: PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Web of Science.

Study selection

Randomized and nonrandomized controlled studies examining the effects of interventions aimed at improving dual-task postural control among community-dwelling older adults were selected.

Data extraction

All studies were evaluated based on methodological quality. Intervention characteristics including study purpose, study design, and sample size were identified, and effects of dual-task interventions on various postural control and cognitive outcomes were noted.

Data synthesis

Twenty-two studies fulfilled the selection criteria and were summarized in this review to identify characteristics of successful interventions.

Limitations

The ability to synthesize data was limited by the heterogeneity in participant characteristics, study designs, and outcome measures.

Conclusion

Dual-task postural control can be modified by specific training. There was little evidence that single-task training transferred to dual-task postural control performance. Further investigation of dual-task training using standardized outcome measurements is needed.

Introduction

In 2020, one out of five people in western countries will be 70 years of age or older.Citation1 Healthy aging is accompanied by changes in sensory and cognitive domains that may lead to balance and gait impairments.Citation2,Citation3 Balance and gait impairments, in turn, contribute to recurrent falls, which are related to increased mortality and morbidity.Citation4 Thirty percent of adults over age 65, and 50% of those over age 85, are likely to have at least one fall.Citation5,Citation6 Consequently, finding effective ways to decrease falls in the elderly may reduce disability and increase life expectancy.Citation7

Although falls are multifactorial,Citation8 impaired postural control is one important factor contributing to falls. Postural control is defined as the ability to control the body’s position in space for the purposes of stability and orientation,Citation9 and is critical during standing balance and walking tasks. Much research has focused on the interplay between postural control and cognition,Citation10 using dual-task postural control paradigms to examine this relationship.Citation11 Dual-task performance refers to the ability to conduct two tasks simultaneously, with dual-task postural control referring to situations when at least one of the tasks involves postural control, such as walking while talking on the phone or while holding a tray. Evaluating dual-task performance is a complex process as it involves the evaluation of each task performed independently as well as in combination. One way of analyzing the performance is by calculating the dual-task cost, defined as the decline in dual-task compared to single-task performance of a task.Citation12–Citation14

Changes associated with aging may lead to deterioration with the performance of each individual task as well as with the dual-task combination. For example, the gait pattern is affected by age, with reduced stride length and gait speed as well as increased lateral sway and stride to stride variability among older adults.Citation15 Executive function is a set of cognitive skills required in order to plan, monitor, and conduct goal-directed complex actions,Citation16 and an important aspect of executive function that tends to deteriorate with aging is the ability to divide or switch attention between the different tasks.Citation17,Citation18 This ability is critical for dual-task performance. In older adults, dual-task postural control deficits have been associated with declines in cognitive functionCitation19,Citation20 and increased risk for falls.Citation21–Citation23

Recent studies have demonstrated the potential for modification of dual-task performance among the elderly.Citation24,Citation25 Specifically, the ability to divide attention between two tasks in order to conduct them simultaneously is modifiable following training.Citation26,Citation27 An important aspect of effective motor learning is training specificity, which refers to training a specific task through repetitive exercises in order to achieve improvements in that task.Citation28 Training in dual-task performance is more complicated than training a discrete movement under single-task condition,Citation29 and the level of specificity required to improve dual-task performance is still unknown. Moreover, dual-task postural control performance is influenced by the types of tasks, their difficulty, and the outcome measured.Citation30,Citation31

There are a growing number of interventions aimed at improving dual-task postural control in healthy older adults. Wollesen and Voelcker-RehageCitation24 performed a systemic review of the dual-task literature to examine the effects of specific versus general training and task combination on dual-task performance. They concluded that dual-task training is more effective than single-task for improving dual-task standing performance, whereas both dual-task and single-task training improved dual-task walking. The current review extends this effort by examining how the application of motor learning principles, such as training specificity, setting, dose, duration, and intensity, may impact the efficacy of dual-task interventions. A better understanding of the effective elements of previous training trials can inform future dual-task interventions designed to improve mobility and reduce fall risk in older adults. Thus, the aims of this systematic review are to: 1) examine the effectiveness of different interventions on dual-task postural control among healthy older adults; and 2) identify key elements of training protocols that effectively improve dual-task postural control in older adults.

Methods

Data sources and searches

A systematic search was performed of the following computerized electronic databases: PubMed (January 1966 through October 2013), CINAHL (January 1982 through October 2013), PsycINFO (January 1900 through October 2013), PEDro (January 1929 through October 2013), and Web of Science (January 1900 through October 2013). Search terms included combinations of the following key words: “dual-task”; “older adults” or “elderly”; “treatment” or “intervention” or “therapy” or “rehabilitation”; “gait” or “balance” or “postural control”. References found by a manual search in identified articles were also reviewed and included as appropriate.

Inclusion criteria and study selection

To be included in this systematic review, a study had to meet the following criteria: 1) participants defined as healthy adults aged 60 years or older; 2) interventions were conducted in a community or clinical setting; 3) interventions required a minimum of 180 minutes of training over at least 3 total days; 4) dual-task postural control was measured as an outcome; and 5) the publication was written in English. Exclusion criteria included participants with a specific neurologic disorder, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, or stroke.

Two reviewers (MA, VEK) screened the abstract search results and decided independently, based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, which studies to include. Results were compared and, when reviewer decisions differed, the full article was reviewed and evaluated to obtain agreement.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Reviewers, who were not blinded to the author or the journal, assessed the quality of each included study in terms of the grade of recommendation and the level of evidence provided using the scoring protocol developed by Portney and Watkins.Citation32 This scale includes ten levels of evidence divided into four levels of recommendations. The highest level of evidence is a meta-analysis and the lowest level is expert opinion.

Studies were summarized according to the following characteristics: methodological quality and level of evidence; study design; sample size; sample characteristics (age and sex); key characteristics of the training protocols (training specificity, content, setting, intensity); assessment time points; outcome measures (for postural control task and concurrent cognitive or motor task); and results. Data synthesis using a meta-analysis was not possible because of the variety of study designs, methodologies, and outcomes measured.

Results

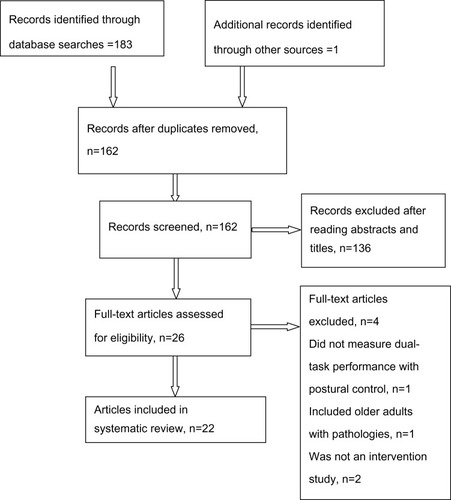

The literature search yielded 162 publications that were screened, with 26 publications reviewed in full. Twenty-two publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review (). Publications were excluded based on the following criteria: 1) not intervention trials (93 publications); 2) population was not appropriate (eg, included younger adults or older adults with a neurologic disorder; 43 publications); 3) did not measure dual-task performance as an outcome (3 publications); or 4) not written in English (1 publication).

Methodological quality and level of evidence

Twenty-two publications were included in this review, with two publications from the same intervention trial (). In terms of level of evidence, eight were considered to be level 1b (randomized clinical trials with narrow confidence intervals) and eight were considered to be 2b (low quality randomized clinical trials). These sixteen studiesCitation26,Citation27,Citation33–Citation46 had some methodological weaknesses; only one study included an intention-to-treat analysis,Citation37 and only four (two from the same trial) incorporated blinded assessors.Citation26,Citation27,Citation43,Citation45 The other six were classified as level 3 (case-control or cohort)Citation47–Citation51 and level 4 (case series).Citation52

Table 1 Level of evidence (n=22)

Sample characteristics

Studies were included in this review only if the participants were adults aged 60 years or older. Sample size ranged from three (one per group)Citation52 to 134.Citation37 The participants were predominantly female.

Sample characteristics varied across studies. Physical and cognitive functioning and the tests used to assess these characteristics varied. Most studies evaluated cognitive status using the mini-mental state examination with inclusion criteria typically based on scores of 24 out of 30 points.Citation26,Citation27,Citation41,Citation46,Citation48,Citation50–Citation52 Physical status was defined using performance-based tests, such as the Berg Balance Scale,Citation26,Citation27,Citation35 Tinetti Test,Citation37 Mini- Balance Evaluation Systems Test (Mini-BEST),Citation47 or the Dynamic Gait Index,Citation41 as well as self-reported walking abilities.Citation26,Citation27,Citation35,Citation38,Citation40,Citation43–Citation45,Citation47–Citation52 Fall history was specified only in four studies.Citation41,Citation46,Citation51,Citation52 Living situation also varied across studies, though most studies involved participants who lived independently in the community ().

Table 2 Studies included in the review (n=22)

Training parameters of interventions

The training protocols incorporated in these studies varied with respect to training specificity (). Both single-task and dual-task approaches were used, and dual-task training incorporated various task combinations. Of the studies incorporating dual-task interventions,Citation26,Citation27,Citation33–Citation38,Citation43–Citation46,Citation52 eleven included postural control tasks as one of the tasks,Citation26,Citation27,Citation33,Citation35–Citation38,Citation43,Citation44,Citation46,Citation52 while two trained dual-task performance on two cognitive tasks.Citation34,Citation45 The other nine studiesCitation39–Citation42,Citation47–Citation51 assessed the effects of single-task postural control training on dual-task postural control.

Table 3 Study characteristics (n=22)

The studies that trained dual-task postural control used different combinations of tasks, with different levels of difficulty in both the cognitive and the postural tasks. For example, Trombetti et alCitation37 combined walking as the postural control task with a variety of motor (eg, handling musical instruments) and cognitive (eg, responding to changes in the beat of the music) tasks. Plummer-D’Amato et alCitation43 trained three different postural control domains (balance, gait, and agility) in combination with four different cognitive tasks (random number generation, word association, backward recitation of words or number sequences, and working memory).

Because dual-task performance can be modified by focusing attention on one task or another, the effect of dual-task training may be influenced by the instructions provided.Citation53 In this review, only the three studies conducted by Silsupadol et alCitation26,Citation27,Citation52 specifically examined the impact of different instructions on dual-task postural control. These studies compared the effect of two sets of instructions – variable priority instructions and fixed priority instructions – on dual-task performance following the same training. Variable priority instructions required the participant to focus on one task at a time (either the postural or the cognitive task) while the fixed priority instructions required the participant to focus on both the postural and cognitive tasks at all times.

Interventions were conducted either one-on-oneCitation26,Citation27,Citation36,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48,Citation49,Citation52 or in group settings (four to 24 people per group),Citation33–Citation35,Citation37–Citation44,Citation47,Citation50,Citation51 with varying levels of supervision. There is no indication that one approach was more effective than the other.

Outcome measures

Balance and walking under both single-task and dual-task conditions was assessed using a variety of measures (). Therefore, there was no common set of standardized measures that could be used to compare changes in dual-task postural control across the studies (). Measures of single-task balance and walking included the Berg Balance Scale, the Dynamic Gait Index, the Timed Up and Go test, postural sway, and various gait parameters (speed, gait stability, center of mass or center of pressure, and variability) assessed during both simple and complex walking tasks. In addition, a number of studies incorporated measures of balance confidence or self-efficacy (Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale, Falls Efficacy Scale) or function (Late Life Function and Disability Index) to examine the effects of training protocols on balance self-efficacy and functioning in daily life.

Table 4 Study outcomes (n=22)

Measures of dual-task balance and walking included postural sway and gait parameters (speed, stability, variability). For dual-task balance and walking, performance on a variety of concurrent cognitive and motor tasks was also assessed. Examples of motor tasks included separating two linked rings or throwing and catching a ball. Examples of cognitive tasks included arithmetic tasks (eg, serial-3 subtractions), working memory tasks (eg, n-back test), or choice reaction time tasks (eg, auditory Stroop test). Dual-task performance was also evaluated using the dual-task cost calculation. In the studies that trained dual-task postural control, some assessed the efficacy of the intervention using trained task combinationsCitation40 while others measured at least one novel task.Citation26,Citation27,Citation52

Dual-task performance changes

From the 22 publications included in this review, 18 demonstrated improvement in some aspect of dual-task performanceCitation26,Citation27,Citation33–Citation40,Citation42,Citation44–Citation49,Citation51,Citation52 whereas four did not.Citation41,Citation43,Citation50,Citation54 Of those showing improvement, three studiesCitation26,Citation27,Citation52 demonstrated improvement for both the postural control task and the concurrent cognitive or motor task. Seven studies demonstrated improvements in the dual-task cost for either postural control tasks or cognitive tasks, but not both.Citation37,Citation40,Citation46–Citation49,Citation51 The other eight did not measure dual-task cost and demonstrated improvement on only one aspect of the tasks combination.Citation33–Citation36,Citation38,Citation39,Citation42,Citation44

Retention

Most studies measured outcomes immediately before and after the intervention, with only five studies examining retention of improvements at different time points after the end of the intervention.Citation27,Citation37,Citation48,Citation49,Citation52 Two studies demonstrated improvements in dual-task cognitive performance that were retained at 2 weeksCitation48,Citation49 and 1 month postintervention.Citation48 Three studies showed some degree of retention in dual-task motor performance for periods ranging from 2 months to 6 months postintervention.Citation27,Citation37,Citation52

Transfer

Eight studies assessed whether training benefits transferred to untrained tasks.Citation26,Citation34,Citation36,Citation38,Citation41,Citation45,Citation47,Citation52 Three studiesCitation26,Citation38,Citation52 examined the effect of dual-task postural control training on novel or untrained dual-task postural control tasks. Silsupadol et alCitation26,Citation52 showed no transfer effect, while Yamada et alCitation38 demostrated a transfer effect. Two studiesCitation41,Citation47 examined whether single training benefits transferred to dual-task postural control, and showed negative results. Three studiesCitation34,Citation36,Citation45 measured the effect of cognitive dual-task training on dual-task performance involving a postural control task and showed transfer to some aspects of dual-task performance (see ).

Discussion

This investigation of the literature on dual-task training demonstrates the potential to increase postural control, thereby improving balance and walking ability in older adults. Furthermore, this systematic review builds on previous research by examining specific training parameters that may impact the efficacy of dual-task interventions.

Training specificity

Overall, evidence supports the effectiveness of specific training to improve dual-task postural control among healthy older adults. Training specificity is a key element of motor learning.Citation55 However, the definition of training specificity is not obvious within the dual-task paradigm since the intended outcome of interventions could include either an improved ability to divide attention between both tasks or to preferentially improve performance of the postural control task. The majority of studies that incorporated direct dual-task training demonstrated improvement on some aspect of dual-task postural control, with only one exception.Citation43 Interventions that trained single-task postural control demonstrated improvement on measures of single-task balance and walking but not on dual-task postural control, with one exception.Citation39 Thus, training dual-task performance specifically, rather than just single-task performance, appears to be a crucial element for interventions that aim to improve dual-task performance. This notion was supported by several studies with the highest level of evidence included in the review.Citation26,Citation27,Citation33–Citation35,Citation37,Citation38

Training content

The interventions that directly trained dual-task postural control employed a variety of task combinations with different levels of difficulty in the postural control and concurrent cognitive or motor tasks. Some task combinations required mainly mathematical skills for the cognitive taskCitation26,Citation27,Citation52 whereas others required verbal and memory skillsCitation41 or auditory skills.Citation37 For the postural control task, most studies used walkingCitation26,Citation27,Citation40,Citation46 or standingCitation35,Citation42,Citation49,Citation50 whereas a few used more complicated tasks such as walking within a narrow pathCitation26 or obstacle crossing.Citation43 Two studies used two motor tasks such as standing while catching and throwing a ball,Citation40 and walking while holding a tray.Citation39 The only studyCitation43 that specifically trained dual-task performance but did not show specific dual-task performance improvements identified a lack of specificity of outcome measures relative to the trained tasks as well as insufficient training hours (4 hours total) as potential explanations for this finding. While the current research suggests that a variety of trained task combinations can improve dual-task performance, future studies should compare how different combinations of tasks impact the efficacy of training.

The impact of specific task combinations on dual-task performance has been widely discussed. Recent reviewsCitation30,Citation31 have examined the effect of different concurrent tasks on walking. Al-Yahya et alCitation31 reported that tasks involving internal interference (ie, requiring top-down processing and driven by factors that are internal to the participantCitation56 such as verbal fluency or mathematical tasks) have a greater influence on gait parameters than external interference or bottom-up tasks (eg, reaction time tasks). Chu et alCitation30 assessed the predictive value of different task combinations for predicting falls. Their meta-analysis indicated that the combination of a mental tracking task and walking is a good predictor for falls among the elderly. Among the studies in this review, only seven studies used this combination in either the training protocolCitation26,Citation27,Citation38,Citation43,Citation46,Citation52 or outcome measure.Citation26,Citation27,Citation36,Citation43,Citation45,Citation47,Citation52 Since fall prevention is an important goal of dual-task interventions, future studies should consider incorporating mental tracking tasks in combination with walking in their protocol and/or outcome measurement.

Instructions and feedback

Variable priority instructions, in which participants were asked to shift their attention back and forth between tasks, appeared to be more effective for improving performance than fixed priority instructions, in which participants focused on either the postural control task or the concurrent cognitive or motor task.Citation26,Citation27,Citation52 However, this direct comparison of instructions was limited to only three studies, one of which was a case series with only three participants. Thus, determining the most effective instructions for dual-task training merits further investigation.Citation57

Moreover, the effect of feedbackCitation55 was not explored by any of these investigations, and different forms of feedback may influence motor learning differently among older adults.Citation58 Feedback focused on knowledge of results (for example, how many meters someone walks) is more effective than feedback focused on knowledge of performance (the nature of the movement). Tailored feedback during dual-task training could target each task separately or both tasks simultaneously. Nevertheless, even the effect of feedback during motor learning of a single task among the elderly was not clear.Citation59 Several issues should be addressed regarding the optimal use of feedback during dual-task training, including: 1) whether feedback is more effective than the absence of feedback during dual-task training among the elderly; and 2) whether feedback on one task at a time is more effective that feedback on both tasks simultaneously during dual-task training.

Training parameters reflecting motor learning

Several parameters of dual-task training may promote motor learning. The setting of training may influence efficacy. The interventions reviewed here were conducted in two distinct settings: group training and one-on-one training. Similar rates of success were found in both settings; ten out of 13 interventions conducted in a group settingCitation26,Citation27,Citation33,Citation35,Citation37–Citation40,Citation42,Citation44,Citation51 demonstrated improvement in some aspects of dual-task, while six out of ten conducted in one-on-one settingsCitation34,Citation36,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48,Citation49 demonstrated successful outcomes. The dose of intervention is an important factor influencing motor learning. The total training hours varied from 5 hoursCitation48 to 25 hoursCitation37 and were spread from 1 week to over 25 weeks.Citation37 For studies that showed improvement in dual-task performance, the length of training sessions ranged from 20 minutesCitation38 to 60 minutes.Citation33–Citation37,Citation39–Citation42,Citation47,Citation49–Citation51 Among studies with the highest methodological quality, Silsupadol et alCitation26,Citation27 conducted the most intensive training, with three sessions per week for 1 month, but Trombetti et alCitation37 conducted the longest intervention, with one session per week for 25 weeks. Both of these studies demonstrated some degree of improvement in dual-task walking, with some retention of benefits, providing support for a high training dose. Among the studies in this review, the variability in training dose, including session intensity, session frequency, and training duration, makes determining the optimal dose of dual-task training challenging.

Outcome measures

There is no gold standard for dual-task assessment, and the studies in this review used various dual-task combinations for their outcome measures. For example, the postural control tasks included obstacle crossing,Citation26,Citation43 over ground walking,Citation34,Citation40,Citation44,Citation45 or standing on a force plate.Citation48 Within similar tasks, a variety of different parameters were assessed. For example, the parameters used to assess performance during walking included frontal plane inclination angle,Citation26 gait variability,Citation37,Citation39 or gait speed.Citation27,Citation40,Citation45

Recent research emphasizes the importance of calculating dual-task cost to understand the underlying mechanism of improvement in dual-task performanceCitation7 and as a sensitive means of assessing fall risk.Citation13,Citation14 Dual-task cost is often calculated using the formula:

and expressed as percentage. Using dual-task cost elucidates the mechanisms underlying the improvement by demonstrating whether improvements are achieved in both tasks or whether improvements in one task occur at the expense of the other task.Citation7 Among the studies included in the current review, only threeCitation41,Citation43,Citation47 calculated the dual-task cost; therefore, comparisons between studies are limited. Agmon et alCitation47 showed that there was a change in the trade-off between cognitive and motor costs between pre- and postintervention. This finding demonstrates changes in prioritization between tasks, but not actual improvement with training.

Retention

Retention of motor skills for up to 1 year has been demonstrated in humans in a laboratory setting.Citation60 Among the studies demonstrating the highest level of evidence, Trombetti et alCitation37 demonstrated the longest retention (12 months), although this was only a partial retention of improvements. Future studies should investigate which practice conditions promote optimal retention as well as the effects of interventions that incorporate ongoing or maintenance programs.

Transfer

Some studies included in this review demonstrated evidence of transfer from trained tasks to novel tasks, but this finding was not uniform. Several studies demonstrated that dual-task postural control training transferred to improvements in novel dual-task combinations.Citation26,Citation38,Citation52 Interestingly, three studies that trained cognitive dual-task performance demonstrated improvements on dual-task postural control.Citation34,Citation36,Citation45 Participants in these studies were trained, while sitting, on tasks that required switching and dividing attention, and the impact on dual-task walkingCitation36,Citation45 and standingCitation34 was assessed. These studies illuminate the potential to improve dual-task postural control by training two cognitive tasks; a protocol that emphasizes the ability to divide or rapidly shift attention. However, these findings were not consistent and may depend on the level of difficulty of the trained tasks compared to the measured task.Citation43

Future directions

This review highlights several questions that merit further exploration. First, although the existing research provides support for the ability to improve dual-task performance, particularly following response to specific dual-task training, it is not clear what effects these improvements have on function in daily life or fall risk. Outcome measures could be expanded to include functional measurements of dual-task performance relevant to daily life, such as putting on a shirt while standing or walking while talking on the phone. In order to understand the influence of dual-task interventions on falls prevention, future studies should incorporate prospective falls assessments over longer-term follow-up periods.

Second, there is a need to further examine the effect of different motor learning parameters, and the interaction between them, on dual-task acquisition, retention, and transfer. These might include the influence of instructions or different modes of feedback, the specificity of training, and the effect of dose on the response to training. In addition, further exploration is needed to determine the efficacy of training within subgroups of older adults, such as those with and without a history of falls or with different cognitive abilities.

Third, Li et alCitation61 emphasized the importance of adopting an ecological perspective when training and measuring dual-task performance. Thus, finding new ways to address dual-task performance in valid ecological environments needs to be explored. Recently, Mirelman et alCitation62 suggested a treadmill with a virtual reality protocol aimed at fall reduction. Such protocols should be tested first on subjects in clinical settings, followed by testing in home-based users. Home-based virtual reality training has the potential to reach larger populations in a complex and safe environment.Citation63

Finally, in order to strengthen the evidence base for improving dual-task postural control, future studies should include larger, more representative samples and use a standard set of outcome measures to allow cross-study comparison. Outcome measures should include walking speed and stride-to-stride variability,Citation7 standard cognitive tasks (such as those that require mental trackingCitation30 or internal interference processing),Citation31 and calculation of dual-task cost for both tasks.Citation64

Limitations

Sixteen randomized clinical trialsCitation26,Citation27,Citation33–Citation46 evaluated the effectiveness of training on dual-task performance on a total of 516 subjects with heterogeneous measures that precluded quantitative synthesis or meta-analysis. Furthermore, the quality of evidence in the present review was mixed, with a risk of bias because some studies did not use randomization. The sample was predominately female, limiting the ability to investigate sex differences in intervention efficacy.

Studies incorporated different intervention protocols and various outcome measures to assess the effectiveness of the interventions. This variability made it difficult to identify specific recommendations about the optimal content or duration of dual-task interventions. The lack of long-term follow-up limits the ability to determine whether the benefits of these interventions were retained, as well as the ability to understand the impact of dual-task postural control training on fall risk.

Conclusion

A synthesis of research examining the effect of different interventions on dual-task postural control suggests that interventions training for balance under single-task conditions can improve balance under single-task conditions, but this improvement does not transfer to dual-task performance.Citation41,Citation47,Citation50 Instead, dual-task training appears to be necessary to improve dual-task performance. While variability amongst studies makes it difficult to identify optimal parameters of interventions, it appears that effective interventions can be conducted in either group or one-on-one settings, with a variety of task combinations incorporated into the intervention. The shortest training schedule of 20 minutes twice a week for 24 weeksCitation38 as well as only five sessions of 1 hour eachCitation34 demonstrated improvement in some aspects of dual-task performance.

Future investigations of interventions to improve dual-task postural control should include focused dual-task training and address tasks that have the highest correlation with fall risk. Moreover, long term follow-up with regard to fall occurrence and daily function should be incorporated in order to better understand whether improved dual-task postural control impacts these areas. Future research should also focus on motor learning elements that may extend the retention of dual-task training benefits in order to determine the most effective protocols. Finally, in order to achieve comparability between interventions, an agreed-upon set of outcome measures should be defined and dual-task cost calculation should be included.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- RubensteinLZFalls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for preventionAge Ageing200635Suppl 2ii37ii4116926202

- MakiBEChengKCMansfieldAPreventing falls in older adults: new interventions to promote more effective change-in-support balance reactionsJ Electromyogr Kinesiol200818224325417766146

- InzitariMBaldereschiMDi CarloAImpaired attention predicts motor performance decline in older community-dwellers with normal baseline mobility: results from the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging (ILSA)J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200762883784317702874

- WoodKMEdwardsJDClayOJWadleyVGRoenkerDLBallKKSensory and cognitive factors influencing functional ability in older adultsGerontology200551213114115711081

- CampbellAReinkenJAllanBMartinezGFalls in old age: a study of frequency and related clinical factorsAge Ageing19811042642707337066

- NevittMCCummingsSRKiddSBlackDRisk factors for recurrent nonsyncopal fallsJAMA198926118266326682709546

- Montero-OdassoMVergheseJBeauchetOHausdorffJMGait and cognition: a complementary approach to understanding brain function and the risk of fallingJ Am Geriatr Soc201260112127213623110433

- FullerGFFalls in the elderlyAm Fam Physician20006172159216810779256

- Shumway-CookASilverIFLeMierMYorkSCummingsPKoepsellTDEffectiveness of a community-based multifactorial intervention on falls and fall risk factors in community-living older adults: a randomized, controlled trialJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200762121420142718166695

- WoollacottMShumway-CookAAttention and the control of posture and gait: a review of an emerging area of researchGait Posture200216111412127181

- Lundin-OlssonLNybergLGustafsonY“Stops walking when talking” as a predictor of falls in elderly peopleLancet199734990526179057736

- DoumasMRappMAKrampeRTWorking memory and postural control: adult age differences in potential for improvement, task priority, and dual taskingJ Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci200964219320119255088

- YamadaMAoyamaTAraiHDua task walk is a reliable predictor of falls in robust elderly adultasJ Am Geriatr Soc201159116316421226689

- BeauchetOAnnweilerCDubostVStops walking when talking: a predictor of falls in older adults?Eur J Neurol200916778679519473368

- HausdorffJMRiosDAEdelbergHKGait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective studyArch Phys Med Rehabil2001828105011494184

- LezakMNeuropsychological AssessmentNew York, NYOxford University Press2004

- RoyallDRPalmerRChiodoLKPolkMJDeclining executive control in normal aging predicts change in functional status: the Freedom House StudyJ Am Geriatr Soc200452334635214962147

- SpringerSGiladiNPeretzCYogevGSimonESHausdorffJMDual-tasking effects on gait variability: The role of aging, falls, and executive functionMov Disord200621795095716541455

- van IerselMBKesselsRPBloemBRVerbeekALRikkertMGExecutive functions are associated with gait and balance in community-living elderly peopleJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200863121344134919126847

- CoppinAKShumway-CookASaczynskiJSAssociation of executive function and performance of dual-task physical tests among older adults: analyses from the InChianti studyAge Ageing200635661962417047008

- ZijlstraAUfkesTSkeltonDLundin-OlssonLZijlstraWDo dual tasks have an added value over single tasks for balance assessment in fall prevention programs? A mini-reviewGerontology2008541404918460873

- NordinEMoe-NilssenRRamnemarkALundin-OlssonLChanges in step-width during dual-task walking predicts fallsGait Posture2010321929720399100

- MuhaidatJKerrAEvansJJPillingMSkeltonDAValidity of simple gait-related dual-task tests in predicting falls in community-dwelling older adultsArch Phys Med Rehabil2014951586424071555

- WollesenBVoelcker-RehageCTraining effects on motor–cognitive dual-task performance in older adultsEur Rev Aging Phys Act2013120

- BeurskensRBockOAge-related deficits of dual-task walking: a reviewNeural Plast2012201213160822848845

- SilsupadolPLugadeVShumway-CookATraining-related changes in dual-task walking performance of elderly persons with balance impairment: a double-blind, randomized controlled trialGait Posture200929463463919201610

- SilsupadolPShumway-CookALugadeVEffects of single-task versus dual-task training on balance performance in older adults: a double-blind, randomized controlled trialArch Phys Med Rehabil200990338138719254600

- Shumway-CookAWoollacottMHAging and postural controlShumway-CookAWoollacottMHMotor Control Translating Research into Clinical Practice3rd edPhiladelphia, PALippincott Williams & Wilkins2007212232

- WulfGAttention and Motor Skill LearningChampaign, ILHuman Kinetics Publishers2007

- ChuYHTangPFPengYCChenHYMeta analysis of type and complexity of a secondary task during walking on the prediction of elderly fallsGeriatr Gerontol Int201313228929722694365

- Al-YahyaEDawesHSmithLDennisAHowellsKCockburnJCognitive motor interference while walking: a systematic review and meta-analysisNeurosci Biobehav Rev201135371572820833198

- PortneyLGWatkinsMPFoundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice3rd edUpper Saddle River, NJPearson and Prentice Hall2009

- HiyamizuMMoriokaSShomotoKShimadaTEffects of dual task balance training on dual task performance ability in elderly people: a randomized controlled trialClin Rehabil2012261586721421689

- LiKZRoudaiaELussierMBhererLLerouxAMcKinleyPABenefits of cognitive dual-task training on balance performance in healthy older adultsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci201065121344135220837662

- MelzerIOddssonLIeImproving balance control and self-reported lower extremity function in community-dwelling older adults: a randomized control trialClin Rehabil201327319520622837541

- MozolicJLLongABMorganARRawley-PayneMLaurientiPJA cognitive training intervention improves modality-specific attention in a randomized controlled trial of healthy older adultsNeurobiol Aging201132465566819428142

- TrombettiAHarsMHerrmannFRKressigRWFerrariSRizzoliREffect of music-based multitask training on gait, balance, and fall risk in elderly people: a randomized controlled trialArch Intern Med2011171652553321098340

- YamadaMAoyamaTHikitaYEffects of a DVD-based seated dual-task stepping exercise on the fall risk factors among community-dwelling elderly adultsTelemed J E Health2011171076877222011054

- DonathLFaudeOBridenbaughSATransfer effects of fall training on balance performance and spatio-temporal gait parameters in healthy community-dwelling seniors: a pilot studyJ Aging Phys Act Epub7222013

- GranacherUMuehlbauerTBridenbaughSBleikerEWehrleAKressigRWBalance training and multi-task performance in seniorsInt J Sports Med201031535335820180173

- HallCDMiszkoTWolfSLEffects of Tai Chi intervention on dual-task ability in older adults: a pilot studyArch Phys Med Rehabil200990352552919254623

- PichierriGCoppeALorenzettiSMurerKde BruinEDThe effect of a cognitive-motor intervention on voluntary step execution under single and dual task conditions in older adults: a randomized controlled pilot studyClin Interv Aging2012717518422865999

- Plummer-D’AmatoPCohenZDaeeNALawsonSELizotteMRPadillaAEffects of once weekly dual-task training in older adults: A pilot randomized controlled trialGeriatr Gerontol Int201212462262922300013

- UemuraKYamadaMNagaiKEffects of dual-task switch exercise on gait and gait initiation performance in older adults: Preliminary results of a randomized controlled trialArch Gerontol Geriatr2012542e167e17122285894

- VergheseJMahoneyJAmbroseAFWangCHoltzerREffect of cognitive remediation on gait in sedentary seniorsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci201065121338134320643703

- YouJHShettyAJonesTShieldsKBelayYBrownDEffects of dual-task cognitive-gait intervention on memory and gait dynamics in older adults with a history of falls: a preliminary investigationNeuro Rehabilitation200924219319819339758

- AgmonMKellyVELogsdonRGNguyenHBelzaBThe effect of enhanced fitness (EF) training on dual-task walking in older adultsJ Appl Gerontol Epub12112012

- BissonEContantBSveistrupHLajoieYFunctional balance and dual-task reaction times in older adults are improved by virtual reality and biofeedback trainingCyberpsychol Behav2007101162317305444

- LajoieYEffect of computerized feedback postural training on postural and attentional demends in older adultsAging Clin Exp Res200416536336815636461

- MelzerIMarxRKurzIRegular exercise in the elderly is effective to preserve the speed of voluntary stepping under single-task condition but not under dual-task conditionGerontology2009551495718547943

- ToulotteCThevenonAFabreCEffects of training and detraining on the static and dynamic balance in elderly fallers and non-fallers: a pilot studyDisabil Rehabil200628212513316393843

- SilsupadolPSiuKCShumway-CookAWoollacottMHTraining of balance under single- and dual-task conditions in older adults with balance impairmentPhys Ther200686226928116445340

- KramerAFLarishJFStrayerDLTraining for attentional control in dual task setting: A comparison of young and old adultsJ Exp Psychol Appl1995115076

- HallEHylemonPVlahcevicZOverexpression of CYP27 in hepatic and extrahepatic cells: role in the regulation of cholesterol homeostasisAm J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol20012811G293G30111408283

- MagillRAMotor Learning and Control: Concepts and Applications11New YorkMcGraw-Hill2007

- AwhEBelopolskyAVTheeuwesJTop-down versus bottom-up attentional control: A failed theoretical dichotomyTrends Cogn Sci201216843744322795563

- Del RosarioNReasons to Switch: The Effects of Priority and Information Presentation on Dual-Task Interleaving Strategies [master’s dissertation]LondonUniversity College London2009

- SheaCHWulfGEnhancing motor learning through external-focus instructions and feedbackHum Mov Sci1999184553571

- Voelcker-RehageCMotor-skill learning in older adults – a review of studies on age-related differencesEur Rev Aging Phys Act200851516

- DayanECohenLGNeuroplasticity subserving motor skill learningNeuron201172344345422078504

- LiKZHKrampeRTBondarAAn ecological approach to studying aging and dual-task performanceCognitive Limitations in Aging and Psychopathology2005190218

- MirelmanARochesterLReelickMV-TIME: a treadmill training program augmented by virtual reality to decrease fall risk in older adults: study design of a randomized controlled trialBMC Neurol20131311523388087

- HolmesJDGuMLJohnsonAMJenkinsMEThe effects of a home-based virtual reality rehabilitation program on balance among individuals with Parkinson’s diseasePhys Occup Ther Geriatr2013313241253

- KellyVEJankeAAShumway-CookAEffects of instructed focus and task difficulty on concurrent walking and cognitive task performance in healthy young adultsExp Brain Res20102071–2657320931180