Abstract

Objectives

Cognitive impairments associated with aging and dementia are major sources of burden, deterioration in life quality, and reduced psychological well-being (PWB). Preventative measures to both reduce incident disease and improve PWB in those afflicted are increasingly targeting individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) at early disease stage. However, there is very limited information regarding the relationships between early cognitive changes and memory concern, and life quality and PWB in adults with MCI; furthermore, PWB outcomes are too commonly overlooked in intervention trials. The purpose of this study was therefore to empirically test a theoretical model of PWB in MCI in order to inform clinical intervention.

Methods

Baseline data from a convenience sample of 100 community-dwelling adults diagnosed with MCI enrolled in the Study of Mental Activity and Regular Training (SMART) trial were collected. A series of regression analyses were performed to develop a reduced model, then hierarchical regression with the Baron Kenny test of mediation derived the final three-tiered model of PWB.

Results

Significant predictors of PWB were subjective memory concern, cognitive function, evaluations of quality of life, and negative affect, with a final model explaining 61% of the variance of PWB in MCI.

Discussion

Our empirical findings support a theoretical tiered model of PWB in MCI and contribute to an understanding of the way in which early subtle cognitive deficits impact upon PWB. Multiple targets and entry points for clinical intervention were identified. These include improving the cognitive difficulties associated with MCI. Additionally, these highlight the importance of reducing memory concern, addressing low mood, and suggest that improving a person’s quality of life may attenuate the negative effects of depression and anxiety on PWB in this cohort.

Introduction

Dementia is one of the principal causes of disability and decreased life quality among older adults.Citation1 Coincident with a worldwide acceleration of dementia burden, there has been a sharp rise in quality of life (QoL) research in this field.Citation2,Citation3 Growing expectations for positive aging amongst older adults and policy concern about the rising costs of age-related health care and institutionalization underlie this trend.Citation2 In fact, low life quality is a strong predictor of adverse health outcomes such as nursing home placement and death.Citation4 Consequently, QoL outcomes are now recommended as essential in dementia prevention and intervention research.Citation5

Despite the universal recognition that QoL is important, no single consensus definition of QoL is available, as definitions vary by theoretical and disciplinary perspectives.Citation1–Citation3,Citation6 A related but distinct concept that is viewed as a marker of successful aging is psychological well-being (PWB).Citation7,Citation8 Recent definitions of PWB focus on eudaimonic well-being, which incorporates psychological concepts such as mastery, social connectedness, and self-acceptance.Citation9 Additionally, research indicates that older adults emphasize PWB, rather than biomedical factors, as they rate well-being as a priority despite the presence of disease and disability.Citation8 In contrast, QoL often refers to hedonic concepts such as satisfaction with different domains of life, including health, finances, and recreation.Citation10 Despite these differences, PWB is often not explicitly examined or is subsumed into the generic concept of QoL.Citation11–Citation17 The terms and constructs PWB and QoL are also frequently applied in research without definitionCitation15,Citation18,Citation19 with many studies confusing the terms and mixing outcome measures or simply avoiding defining terms.Citation15,Citation18

Maintaining life quality is highly relevant for those with neurodegenerative disorders as there is no effective cure.Citation20 Jonker et al provided a three-tiered hierarchical model of QoL with PWB as the ultimate focusCitation17 to improve treatment outcomes in dementia.

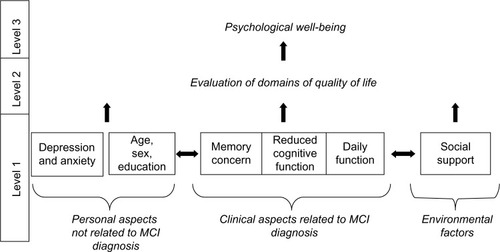

However, for the purposes of dementia prevention, interventions are increasingly targeting those in the early preclinical stage of the disease,Citation21 often diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI).Citation22 However, the vast majority of studies have focused upon dementiaCitation20 and no model of PWB has been developed for MCI. Additionally, clinical trials that enroll people with MCI have generally not examined QoL and PWB as outcome variables, with a recent review of cognitive interventions in MCI indicating that only two of 14 trials had QoL outcomes.Citation23 Therefore, based upon Jonker’s 2004 model for Alzheimer’s disease, we present a theoretical hierarchical model of PWB in MCI, shown in , in order to inform intervention. This theoretical model includes both objective measures of disease and subjective measures of PWB and QoL, consistent with recent recommendations.Citation24

Figure 1 Hierarchical model of psychological well-being in mild cognitive impairment based upon Jonker’s 2004 model of quality of life for dementia.

Abbreviation: MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

Level 1 “clinical aspects of disease” (Jonker’s term)Citation17 are operationalized as the diagnostic criteria for MCI: subjective memory concern; mild cognitive impairment assessed on objective cognitive measures; and intact activities of daily living.Citation22 “Clinical aspects not related to dementia” (Jonker’s term)Citation17 includes covariates age, education, sex, and negative affect. External environment is defined here as social network, which has been found to influence health and life quality.Citation25

Level 2 “evaluation of each domain” (Jonker’s term)Citation17 is operationalized as self-ratings of satisfaction across different aspects of life including health. Level 3 PWB, as defined above, is similar to the concepts of “positive productive aging” or “successful aging”,Citation8,Citation26 and is the ultimate clinical outcome.

It was originally postulated that level 1 factors would be interrelated and have discrete links with level 2 QoL and level 3 PWB, and that changes in clinical aspects of disease would be reflected in changes in evaluations of PWB.Citation17 However, this model was never empirically tested and it has been argued that such evaluation of QoL and PWB is necessary to advance our understanding of the field.Citation27 Therefore, the purpose of this study was to empirically test the Jonker et al 2004 model of PWB within a group of older adults diagnosed with MCI. Based upon our model, it was hypothesized that:

level 1 clinical aspects of MCI, negative affect, and social environment will be interrelated;

level 1 factors will be related to the level 2 evaluations of quality of life factors;

level 1 and level 2 factors will both be related to PWB; and, importantly;

level 2 factors will mediate the relationship between level 1 factors and PWB.

Methods

The data were drawn from the Study of Mental Activity and Regular Training (SMART) trial published by Gates et alCitation28 and for which ethical approval was obtained from the Sydney South West Area Health Service (HREC Ref.08/RPAH/106), University of Sydney Human Research Ethics (HREC: 06-2008/11094), University of New South Wales (HREC: 08152), and signed informed consent was obtained from all participants (ANZCTR 83075).

Participants

Participants (N=100) were enrolled in the Sydney SMART trialCitation28 and were community-dwelling adults aged over 55 years with diagnosis of MCI: self-reported memory complaint; objective cognitive deficit based on a mini-mental status examination (MMSE)Citation31 score of 23–29; and no dementia (Clinical Dementia Rating of 0.5 or below).Citation32 Primary exclusion criteria of the SMART trial were clinical depression, unstable medical conditions, and other progressive neurological diseases. Full inclusion and exclusion details can be found in our published protocol.Citation28

Measures

For details of the full neuropsychological battery and psychological test instruments, see the SMART protocol.Citation28

Level 1 clinical aspects of MCI were the three common diagnostic criteria measured separately. Subjective memory concern can be validly assessed via memory complaint and a person’s self-rated capacity to perform daily memory tasks,Citation29 and both methods were used here. A study-specific questionnaire of seven items relating to severity of current memory complaints provided a memory complaint score (MCS), and self-rated memory function was assessed with the Memory Awareness Rating Scale-Memory Function Scale (MARS-MFS).Citation30 Cognitive function was measured with the MMSE,Citation31 the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog)Citation32, and multidomain neuropsychological measures. These measures were: Trail Making Test (TMT);Citation33 Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT);Citation33 Logical Memory I and II subtests of the Wechsler Memory Scale 3rd Edition;Citation34 the ADAS-Cog three memory recall trials with a total score of correctly-recalled words for the assessment of list learning; Benton Visual Retention Test-Revised 5th Edition;Citation35 controlled oral word association (COWAT); Category fluency (animal naming);Citation33 and the Matrices and Similarities subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 3rd Edition.Citation36 Daily function was measured on the Bayer-Activities of Daily Living (B-ADL)Citation37 as a self-rating scale of capacity to perform instrumental activities of daily life.

Level 1 nonclinical MCI factors were environment and negative affect. Negative affect was measured with the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) 15-items scale,Citation38,Citation39 and with the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale 21(DASS).Citation40 Satisfaction with social environment was assessed on the eleven items of the abbreviated Duke Social Support Index (DSSI)Citation41 providing a satisfaction score regarding the size and structure of respondents, social network.

Level 2 evaluations of QoL involved measuring hedonic aspects of QoL obtained from the 15-item Quality of Life Scales (QOLS),Citation42 the SF-36v2™,Citation43 and the Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS).Citation12 The QOLS measures level of satisfaction across five domains of life: material and physical well-being; relationships with other people; social, community, and civic activities; personal development and fulfillment; and recreation.Citation42 The Scale of Psychological Well-Being (SPWB) and the QOLS have been differentiated as measuring two distinct constructs.Citation10 The SF-36v2™ is a clinician-administered scale on which respondents rate eight areas: physical functioning; role functioning; bodily pain; general health; vitality; social functioning; role–emotional functioning; and mental health. The scoring algorithm generates two summary scores; a physical component score (SF-36 PCS) and mental component score (SF-36 MCS). The LSS is a global validated single item seven-point delighted–terrible rating scale.Citation6

Level 3 psychological well-being concerned with eudaimonic factors measured with the 84-item SPWBCitation13 across six domains – autonomy; environmental mastery; personal growth; positive relations with others; purpose in life; and self-acceptance – with respondents required to rate their level of agreement with each item.

Procedures

All results reported here were derived from baseline data collected before randomization. Sociodemographic and health status data were obtained through face-to-face interviews and assessment using structured interviews and self-report scales. One experienced neuropsychologist acquired all cognitive and psychological data.

Statistical analysis

Demographic details are reported as means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. The distributions of all continuous variables used in the following analyses were examined and, if necessary, transformed to approximate the normal distribution more closely. Preliminary regressions were performed between PWB and all variables within the same level to avoid issues associated with colinearity. Relationships within level 1 variables (clinical aspects of MCI, social support, and negative affect) were analyzed using a series of regression analyses. For these analyses, each independent variable was entered separately into each of the regression models, together with control variables age, sex, education. Negative effect was entered as a control variable where appropriate to the particular analysis. Multivariate regression analyses were used to examine significant level 1 and level 2 predictors of SPWB and significant level 1 predictors of level 2 variables. Model reduction was carried out using the backwards elimination method with the P-value for item removal set at 0.10. Regression using the stepwise procedure was performed to isolate the relative contribution of each level in the hierarchical model. Potential mediation of the effects of level 1 variables on SPWB by level 2 variables was examined using the method described by Baron and Kenny.Citation44 All data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A P-value of <0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

There are no missing values in any table as a full data set was acquired. Demographic information is shown in . The sample had a mean age of 70 years, was predominantly female (68%), and all participants had completed secondary schooling (mean 13.4 years of schooling). Mild cognitive impairment was evident (mean MMSE 27.47, SD 1.46: mean Clinical Dementia Rating 0.14, SD 0.22). Descriptive statistics for the measures of clinical aspects of MCI, negative affect, social support, evaluations of QoL, and PWB are presented in . Scores on the DASS-depression and DASS-anxiety scales were transformed with square root transformation due to nonnormality of the distributions prior to analyses. Memory complaints (mean 2.84, SD 1.37) and intact capacity to perform activities of daily living (mean score 0.13, SD 0.06) were evident, commensurate with diagnosis of MCI. The cohort had minimal levels of depression consistent with exclusion criteria and high levels of life satisfaction (LSS mean 2.7, SD 1.0), QoL (QOLS mean 87.1, SD 11.6), and PWB (SPWB mean 249.4, SD 33).

Table 1 Baseline demographic characteristics of participants

Table 2 Means (standard deviation) and score range (maximum score) for all measures

The relationships between clinical aspects of MCI and other level 1 variables

A series of regression analyses with the memory concern variables as dependent variables (DVs) on each cognitive variable and B-ADL as an independent variable (IV), and B-ADL (DV) on each cognitive variable (IV) are presented in . Demographics and negative affect variables were included in each analysis as control variables. Women reported significantly more dependency in activities of daily living (B-ADL; beta regression value (β) 0.20, P<0.05) compared to men while men had lower self-rated memory function (MARS-MFS; β −0.24, P<0.05) than women. Younger participants had greater memory complaints (MCS; β −0.25, P<0.05). More memory complaints (MCS) were significantly linked to greater cognitive difficulty (ADAS-Cog; β 0.21, P<0.05), worse memory (Logical I; β − 0.24, P<0.05; Logical II; β −0.22, P<0.05), and (β −0.21, P<0.05). Higher self-rated memory function (MARS-MFS) was significantly associated with better memory performance (Logic II; β 0.20, P<0.05) and less cognitive difficulty (ADAS-Cog; β −0.22, P<0.05). Greater difficulties on B-ADL were significantly associated with higher memory complaint (MCS; β 0.25, P<0.05) and lower self-rated memory function (MARS-MFS; β −0.35, P<0.05), but not with objective cognitive function.

The results of regression analyses for the effects of clinical aspects of MCI on social support and negative affect variables are presented in . Each of the clinical aspects of MCI variables were entered singly into each regression equation, with age, sex, and education included in each analysis as control variables. Higher education was related to fewer DASS-depression symptoms (β −0.22, P>0.05) and DASS-anxiety symptoms (β −0.27, P<0.05), but age and sex were not related to negative affect scores.

Generally, both subjective and objective cognitive function and negative affect were inversely related, as anticipated. After controlling for demographics, increasing memory complaint (MCS) was significantly associated with more depressive symptoms on GDS (β 0.29, P<0.005). Better self-rated memory function (MARS-MFS) was significantly associated with fewer depressive symptoms (GDS; β −0.29, P<0.005; DASS-depression; β −0.25, P<0.05) and stress (β −0.25, P<0.05). Worse ADAS-Cog performance was related to more depressive symptoms on GDS (β 0.28 P<0.005) and greater stress (DASS-stress; β 0.34, P<0.05). Higher delayed memory on Logical II was associated with lower depressive symptoms (GDS; β −0.22, P<0.05) and better visual memory with lower stress (DASS-stress; β −0.35, P<0.001), depressive symptoms (DASS-depression; β −0.28, P<0.05), and anxiety symptoms (DASS-anxiety; β −0.24, P<0.05). Worse verbal fluency (COWAT) was associated with greater depressive and anxiety scores (DASS-depression; β −0.36, P<0.05; DASS-anxiety; β −0.29, P<0.05). Slower TMTA performance was significantly associated with more negative affect (DASS-depression; β 0.33, P<0.05; DASS-anxiety; β 0.32, P<0.05; DASS-stress; β 0.21, P<0.05). Faster visual–motor speed on Symbol Digit Modalities Test was significantly linked to lower depression (DASS-depression; β −0.28, P<0.05) and anxiety (DASS-anxiety β −0.22, P<0.05). By contrast, functional independence (B-ADL score) was not related to any negative affect measure.

Higher satisfaction with social support (DSSI) was associated with better self-reported memory function (MARS-FCS; β 0.21, P<0.05), less cognitive difficulty (ADAS-Cog; β −0.26, P<0.05), and better verbal fluency (COWAT; β 0.23, P<0.05).

Hierarchical model: relationships between levels 1, 2, and 3

Regression of level 3 SPWB (DV) onto each single independent variable, and multivariate regression of SPWB on all level 1 variables (clinical aspects of MCI, mood, social support) and on both level 1 and level 2 evaluations of life quality variables combined, are presented in . In the reduced models, ratings of SPWB were not significantly associated with any demographic variable. The final set of significant predictors of SPWB, with both level 1 and 2 variables as IVs, were level 1 objective cognitive function, self-rated memory function and negative affect, and level 2 evaluations of QoL. Better SPWB was associated with lower verbal fluency (COWAT; β −0.23, P<0.00) but better matrices performances (Matrices; β 0.22, P<0.05), cognitive level (MMSE; β 0.19, P<0.05), and self-rated memory function (MARS-FCS; β 0.29, P<0.05), lower anxiety (β −0.25, P<0.05) and depression (DASS-depression; β −0.19, P<0.05), and better evaluations of QoL (QOLS; β 0.39, P<0.05). In multivariate analyses, higher SPWB was associated with lower physical component QoL (SF36 PCS; β −0.23, P<0.05) and was unrelated to mental component (SF36 MCS; β −0.12, P>0.1) or LSS (β −0.10, P<0.1). The final reduced regression model of SPWB, obtained using backwards elimination procedure, is shown in .

Table 3 Regression analyses for the effects of level 1 variables, and the effects of level 1 and level 2 variables combined, on SPWB

Hierarchical regression analysis, using the variables in the reduced model shown in , was performed to determine the contribution of the clinical aspects of MCI, after controlling for negative affect, and the contribution of the evaluation of QoL variables in addition to all other variables in the model. Depression and anxiety were entered first, followed by clinical aspects of MCI (memory function and cognitive function), and then evaluations of QoL at step 3. The full model explained more than half the variance of SPWB (total R2=0.61; P<0.001). Memory concern and cognitive function made an additional significant contribution to the explanation of variance in SPWB (R2 change =0.17; P<0.001) above the contribution of depression and anxiety. Evaluations of QOLS and SF36PCS were entered last and contributed an additional R2 of 0.19 (P<0.001), indicating that level 2 evaluations of QoL predict additional variance in SPWB above level 1. A depiction of the final regression model is shown in .

Table 4 Hierarchical regression model of level 1 and level 2 variables on the Scale of Psychological Wellbeing (SPWB)

Mediation

Applying Baron and Kenny’s criteria for mediation,Citation44 only two level 2 variables (QOLS and SF36-PCS) had statistically significant effects on SPWB when all variables were entered (see ), and could potentially be included in mediation analyses. Two separate linear regressions were conducted with QOLS and SF36-PCS as DVs and level 1 variables as IVs providing reduced models following backwards elimination shown in . Next, only those level 1 variables that had statistically significant effects on SPWB (without QOLS and SF36-PCS in the equation []), and on QOLS and SF36-PCS (), satisfied Baron and Kenny’s criteria for inclusion. Inspection of the results in and S3 indicates that DASS-anxiety and DASS-depression, social network DSSI, memory function MARS-MFS, Matrices, Logical I, and COWAT are mediated by level 2 QOLS and SF36 PCS.

Discussion

This study provides empirical support for a hierarchical model of PWB in MCI that explains 61% of the variance as measured here. The hypotheses that level 1 clinical aspects of MCI, depression, and social support would be interrelated, and that those primary aspects would influence secondary evaluations of life quality, were also supported. Further, the postulate that tertiary-level PWB would be significantly influenced by primary MCI and depression, as well as secondary evaluations of QoL, was supported. Moreover, our hypothesis that evaluations of QoL would mediate the effect of lower-level 1 variables on PWB was partially supported. Results obtained here are hence consistent with findings from studies of older adults that suggest that lower QoL and well-being are associated with higher memory concern,Citation29,Citation45 cognitive deficits,Citation20 and negative affect.Citation46 However, unlike those studies, analyses here examined clinical aspects of MCI, negative affect, and QoL within the one cohort, thus testing a more comprehensive model in a clinically relevant sample.

Our examination of clinical aspects of MCI indicated that memory concern in the form of complaints and self-rated memory function was significantly associated with cognitive and daily function, independently of negative affect. Memory concern was also significantly linked to a low satisfaction with social support and greater depressive symptoms. With the exception of cognitive and daily functions, which were not associated, all other level 1 factors were significantly linked together. These findings therefore provide some support for Jonker’s conceptualizationCitation17 of primary disease and nondisease factors relevant to PWB.

Our findings also align with research that memory concerns are indeed reported by individuals with objective evidence of cognitive decline.Citation47,Citation48 Many studies have not reported significant associations between memory concern and cognitive function, finding rather that memory concern is related to psychopathology, personality traits such as neuroticism, and negative cognitive bias.Citation29 In our study, however, the association between memory concern and cognition was independent of the links between memory complaint and self-rated memory function, and negative affect.

Lower cognitive performance in our MCI sample was associated with higher levels of negative affect, consistent with previous MCI research.Citation49 Individuals with depression were excluded from this study and self-reported symptom levels were exceedingly low; nonetheless, mixed associations between cognition and negative affect were evident depending upon the scale. This highlights a previously known issue: that different depression scales can provide conflicting results.Citation50 Moreover, the nature of any causal links between cognitive function and depression is controversial. In healthy adults, some research has suggested that perceived deterioration in memory may lead to anxiety, possibly fear about developing dementia, with depression as a natural response.Citation51 Hence, poor cognitive function may lead to depression. Other research indicates a concurrent incidence between MCI and depressive symptoms. Therefore, another possibility is that they are comorbid conditions and the presence of hippocampal atrophy in both cognitive impairment and depression suggests a common biological process as well. Yet another alternative is that depression is a significant risk factor for subsequent cognitive deterioration.Citation49,Citation52

At this time, there is no consensus in this area. However, given that negative affect was here independently associated with cognitive function, social support, memory concern, and PWB, understanding and identifying negative affect in MCI represents a valuable potential treatment target.

Level 1 memory concern, cognitive function, capacity to complete daily activities, social support, and negative affect were significantly related to level 2 evaluations of QoL. Specifically, results here indicate that satisfaction with social support has a large and significant positive association with QoL, consistent with previous research.Citation25 The association between memory concern and QoL is controversial because of the role of depression and negative cognitive bias or “affective distortion”.Citation46 In contrast, negative affect, specifically anxiety and depression, in this study was significantly linked to lower evaluations of QoL; a finding entirely consistent with previous research. For example, a review of Health Related Quality of Life (HR-QoL) in dementia indicated that decreased QoL was consistently associated with depression.Citation53 Similarly, evaluations of QoL have been found to deteriorate with depression in clinical settings.Citation54 Thus, findings here suggest complex interrelationships similar to those reported in a previous study of community dwelling elderly, which found that increasing severity of memory concern was associated with multiple factors including poor social network, negative age stereotyping, and depression.Citation55

Within this study, cognitive function was also related to QoL. In mild dementia, lower level of cognition is linked to lower health related QoL.Citation56 However, different cognitive functions had different relationships with each QoL outcome. A review examining the influence of specific cognitive functions on HR-QoL in neurological disease similarly identified differential impacts.Citation57 A total of 92% of participants in this study were identified as having nonamnestic MCI. The cognitive deficits and risk profiles associated with nonamnestic MCI are heterogeneous, giving rise to the subtyping of MCI.Citation58 Therefore, it is plausible that the various cognitive deficits in this cohort are differentially associated with QoL and further research is required.

Finally, analysis of level 3 PWB indicated that primary level clinical aspects of MCI and depression, and level 2 evaluations of QoL, were both predictive of PWB. Subjective memory concern was directly linked to PWB after controlling for depression. This result is consistent with several previous studies;Citation29,Citation45 however, conflicting results have also been noted.Citation59 Results here suggest that subjective level of complaint and self-ratings of memory function have differential impact upon PWB. Inconclusive and equivocal findings regarding QoL and memory concern may therefore, in part, reflect different assessment approaches for subjective memory concernCitation60 and QoL.Citation5 Recommendations have been made to examine the subdivisions of subjective cognitive complaint,Citation21 and this is supported here. Consequently, two practical clinical conclusions to draw from this study are, first, that measuring self-rated memory function in daily life may be more useful in understanding PWB than focusing on the presence or absence of complaint, and, second, that improving a person’s memory function through external or internal aids may significantly improve PWB, potentially due to an increased sense of self efficacy.

The lack of consensus regarding the etiology of memory concern,Citation61 and its association with psychopathology, has reinforced the notion that concern is purely subjective. As a result, individuals with complaints may be dismissed by health professionals as the “worried well”.Citation62 However, as findings here suggest, concern may be linked to subtle cognitive difficulties and reduced daily function, and it is possible that adults perceive such changes when traditional cognitive measures are insensitive.Citation63 Furthermore, results from this study suggest that memory concerns in MCI are linked to lower ratings of QoL and PWB. In healthy adults, perceived deterioration in memory has been found to lead to anxiety.Citation51 Here, anxiety was linked to reduced psychological well-being. Consequently, this evidence supports a general recommendation that memory concerns should not be underestimated in clinical settings.Citation64 Clinicians’ responses could focus on adjusting expectations, psychoeducation to alleviate anxiety, and practical strategies to minimize the impact of cognitive deficits.

Our results also indicate that early subtle cognitive deficits are directly and significantly associated with PWB after controlling for depression. These results are consistent with findings from a systematic review that identified that even a mild deterioration in cognition has significant psychological impact. However, unlike previous research, results here also suggest that the negative impact of mild depressive and anxiety symptoms on PWB are mediated by evaluations of life quality across multiple domains. This finding may also have clinical implication. By improving aspects of a person’s life, such as introducing increasing social support, recreational pursuits, and supporting community access, it is possible that the deleterious impact of depression and anxiety on PWB may be mitigated.

Previous research indicates that frailty and cognitive deficits determine QoL in MCI and early stage dementia. Therefore, not surprisingly, lower cognitive function was significantly associated with compromised physical-QoL measured on the SF36 PCS in this study. Contrary to expectation in the multivariate model, high SF36 PCS was related to a significant reduction in psychological well-being, but mediated the impact of memory concern, cognitive difficulties, and negative affect on psychological well-being.

This study has a number of limitations due to methodological constraints. The cross-sectional nature of the study restricts the extent to which causal inferences can be made. The sample was small, comprising only 100 MCI individuals with subtle cognitive deficits (mean MMSE 27.4) and who were motivated enough to volunteer for the study, and, thus, their wider representativeness is not clear. Therefore, given this MCI profile, another possible limitation that remains is the evolving nature of MCI diagnosis.Citation65 The impact of more severe memory deficits associated with amnestic-MCI was also not examined, and so results here may underestimate the burden of disability and reduced PWB in this group. In addition, being a convenience sample with psychopathology excluded, the associations between clinical depression and all factors, particularly PWB, could not be examined. Lastly, the sample completed a high level of education, and, within this range, lower education was significantly related to lower mood. Therefore, results may not necessarily apply to less educated individuals.

Individuals with MCI encounter various unique practical and emotional difficulties. In this study, we formally tested a hierarchical model in which clinical aspects of disease influence QoL, which in turn influences PWB. We found that clinical aspects of MCI were significantly associated with reduced PWB, whilst high QoL was associated with high PWB. Results here indicate that, for individuals with the subtlest of cognitive changes, their PWB may be at risk. Intervention targeting emotional, functional, and social factors, in addition to cognitive health, may optimize PWB outcomes, and, ideally, such treatment should commence when individuals first present with concerns for their memory function.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the multicenter longitudinal SMART trial funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia Dementia Research Grant, project grant ID No 512672 from 2008–2011. Additional funding for a research assistant position was sourced from the NHMRC Program Grant ID No. 568969, and the trial was supported by the University of Sydney and the University of New South Wales. MV was supported by a NHMRC Clinical Career Development Fellowship (1004156). We wish to acknowledge the contributions of Nalin Singh, Bernhard T Baune, and Henry Brodaty who were involved in the funding application, design, and general supervision of the SMART trial. In addition we acknowledge the roles of Michael Baker, Nidhi Jain, Nasim Foroughi, Jacinda Meiklejohn, and Guy Wilson in trial administration, recruitment, data collection, and data entry. Lastly, we are indebted to the participants who devoted their time to this project.

Supplementary material

Table S1 Regression of memory complaint and subjective memory function measures on cognitive and daily function variables, and daily function on cognitive variables controlling for demographic and negative affect variables

Table S2 Regression analyses level 1 clinical aspects of MCI and social support and negative affect

Table S3 Regression analyses for the effects of level 1 variables on level 2 evaluations of quality of life variables

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Schölzel-DorenbosCJvan der SteenMJEngelsLKOlde RikkertMGAssessment of quality of life as outcome in dementia and MCI intervention trials: A systematic reviewAlzheimer Dis Assoc Disord200721217217817545745

- BrownJBowlingAFlynTModels of QoL: A Taxonomy, Overview and Systematic Review of the LiteratureEuropean Forum on Population Ageing Research2004

- St JohnPMontgomeryPRCognitive impairment and life satisfaction in older adultsInt J Geriatr Psychiatry20102581482120623664

- BillottaCBowlingANicoliniPOlder people’s quality of life of life (OPQOL) scores and adverse health outcomes at one-year follow-up. A prospecive cohort study study on older outpatients living in the communty in ItalyHealth Qual Life Outcomes201197221892954

- HalvorsrudLKalfossMThe conceptualization and measurement of quality of life in older adults: A review of empirical studies published during 1994–2006Eur J Ageing200744229246

- CumminsRAOn the trial of the gold standard for subjective wellbeingSoc Indic Res199543307334

- DeppCJesteDVDefinitions and Predictors of Successful Aging: A Comprehensive Review of Larger Quantitative StudiesAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200614162016407577

- DeppCAGlattSJJesteDVRecent advances in research on successful or healthy agingCurr Psychiatry Rep2007971317257507

- LehnertKSudeckGConzelmannASubjective well-being and exercsie in the second half of life: a critical review of the theoretical approachesEur Rev Aging Phys Act2012987102

- KeyesCLShmotkinDRyffCDOptimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditionsJ Pers Soc Psychol20028261007102212051575

- ArentSMLandersDMEtnierJLThe effects of exercise on mood in older adults: A meta-analytic reviewJ Aging Phys Act20008407430

- AndrewsFMWitheySBSocial Indicators of Well-Being: America’s Perception of Life QualityNew YorkPlenum Press1976

- RyffCDKeyesCLThe structure of Psychological Well-Being revisitedJ Pers Soc Psychol19956947197277473027

- NetzYWuMJBeckerBJTenebaumGPhysical activity and psychological well-being in advanced age: A meta-analysis of intervention studiesPsychol Aging200520227228416029091

- LawtonMPAssessing quality of life in Alzheimer disease researchAlzheimer Dis Assoc Disord199711Suppl 691999437453

- RyanRMDeciELOn happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-beingAnnu Rev Psychol20015214116611148302

- JonkerCGerritsenDLBosboomPRVan Der SteenJTA model for quality of life measures in patients with dementia: Lawton’s next stepDement Geriatr Cogn Disord200418215916415211071

- RingLHöferSMcGeeHHickeyAO’BoyleCAIndividual quality of life: Can it be accounted for by psychological or subjective well-being?Soc Indic Res2007823443461

- DearKHendersonSKortenAWell-being in Australia. Findings from the national survey of mental health and well-beingSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol200237507509

- MhaoláinAMGallagherDCrosbyLFrailty and quality of life for people with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairmentAm J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen2012271485422467414

- MarkRESitskoornMMAre subjective cognitive complaints relevant in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease? A review and guidelines for healthcare professionalsRev Clin Gerontol20132316174

- WinbaldBPalmerKKivipeltoMMild Cognitive impairment-beyond controversies, towards consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive impairmentJ Intern Med200425624024615324367

- HuckansMHutsonLTwamleyEJakAKayeJStorzbachDEfficacy of cognitive rehabilitation therapies for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in older adults: Working toward a theoretical model and evidence-based interventionsNeuropsychol Rev201323638023471631

- BanerjeeSSmithSCLampingDLQuality of life in dementia : more than just cognition. An analysis of associations with quality of life in dementiaJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20087714614816421113

- BowlingAHankinsMWindleGBilottaCGrantRA short measure of quality of life in older age: the performance of the brief Older Person’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (OPQOL-Brief)Arch Gerontol Geriatr20135618118722999305

- LivingstonGCooperCWoodsJMilneAKatonaCSuccessful ageing in adversity: The LASER-AD longitudinal studyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200879664164517898031

- CumminsRAFostering quality of lifeInPsych The Bulletin of the Australain Psychological Society2013351811

- GatesNValenzuelaMSachdevPSStudy of Mental Activity and Regular Training (SMART) in at risk individuals: A randomised double blind, sham controlled, longitudinal trialBMC Geriatr2011111921510896

- MontejoPMontenegroMFernándezMAMaestúFMemory complaints in the elderly: Quality of life and daily living activities. A population based studyArch Gerontol Geriatr20125429830421764152

- ClareLWilsonBACarterGRothIHodgesJRAssessing awareness in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease: Development and piloting of the memory awareness rating scaleNeuropsychol Rehabil2002124341362

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR‘Mini-Mental State’: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res1975121891981202204

- RosenWGMohsRCDavisKLA new rating scale for Alzheimer’s diseaseAm J Psychiatry198414111135613646496779

- LezackMHowiesonDBLoringDWNeuropsychological Assessment4th edOxford University Press2004

- WechslerDWechsler Memory Scale 3rd EditionHarcourt Brace and Company1997

- SivanABBenton Visual Retention Test 5th EditionHarcourt Brace and Company1992

- WechslerDWechsler Adult Intelligence Scales 3rd EditionHarcourt Brace and Company1997

- HindmarchILehfeldHde JonghPErzigkeitHThe Bayer Activities of Daily Living Scale (B-ADL)Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord19989Suppl 220269718231

- BrinkTLYesavageJALumOHeersemaPAdeyMRoseTLScreening tests for geriatric depressionClin Gerontol198213743

- SpreenOStraussEA Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests Administration, Norms, and Commentary2nd edOxford University Press1998

- LovibondSHLovibondPFManual for the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS) 1993Psychology Foundation MonographUniversity of New South Wales NSW 2052Australia

- KoenigHGWestlundREGeorgeLKHughesDCBlazerDGHybelsCAbbreviating the Duke Social Support Index for use in chronically ill elderly individualsPsychosomatics19933461698426892

- BurkhardtCSAndersonKLThe Quality of Life Scale (QOLS): reliability, validity and utilizationHealth Qual Life Outcomes200316014613562

- WareJESherbourneCEThe MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selectionMed Care19923064734831593914

- BaronRMKennyDAThe moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerationsJ Pers Soc Psychol198651117311823806354

- TriggRWattsSJonesRTodAPredictors of quality of life ratings from persons with dementia: the role of insightInt J Geriatr Psychiatry201126839121157853

- BerwigMLeichtHHartwigKGertzHJSelf-rated quality of life in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: The problem of affective distortionGeroPsych (Bern)20112414551

- MitchellAJThe clinical significance of subjective memory complaints in the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and dementiaInt J Geriatric Psychiatry20082311911202

- JessenFWieseBCvetanovskaGPatterns of subjective memory impairment in the elderly: Association with memory performancePsychol Med200737121753176217623488

- RosenbergPBMielkeMMApplebyBSOhESGedaYELyketsosCGThe association of neuropsychiatric symptoms in MCI with incident dementia and Alzheimer diseaseAm J Geriatr Psychiatry20132168569523567400

- DefrancescoMMarksteinerJDeisenhammerEAHinterhuberHWeissEMAssociation of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and depressionNeuropsychiatr2009233144150 German19703379

- VerhaeghenPGeraertsNMarcoenAMemory complaints, coping, and well-being in old age: A systemic approachGerontologist200040554054811037932

- van den KommerTNComijsHCAArtsenMJHuismanMDeegDJHBeekmanATFDepression and cognition: how do they interrelate in old age?Am J Geriatr Psychiatry20132139841023498387

- BanerjeeSSamsiKPetrieCDWhat do we know about quality of life in dementia? A review of emerging evidence on the predictive and explanatory value of disease specific measures of health related quality of life in people with dementiaInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200924152418727132

- NetuveliGBlaneDQuality of life in older agesBr Med Bull20088511312618281376

- DerouesnéCAlperovitchAArvayNMemory complaints in the elderly: A study of 367 community-dwelling individuals from 50 to 80 years oldArch Gerontol Geriatr Suppl198911511632757729

- HurtCSBanerjeeSTunnardCInsight, cognition and quality of life in Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201081333133619828481

- MitchellAJKempSBenito-LeónJReuberMThe influence of cognitive impairment on health-related quality of life in neurological diseaseActa Neuropsychiatr201022213

- SachdevPSLipnickiDMCrawfordJRisk profiles of subtypes of mild cogitive impairment: the sydney memory and ageing studyJ Am Geriatr Soc201260243322142389

- MolMCarpayMRamakersIRozendaalNVerheyFJollesJThe effect of perceived forgetfulness on quality of life in older adults; a qualitative reviewInt J Geriatr Psychiatry20072239340017044138

- AbdulrabKHeunRSubjective Memory Impairment. A review of its definitions indicates the need for a comprehensive set of standardised and validated criteriaEur Psychiatry20082332133018434102

- DuxMCWoodardJLCalamariJEThe moderating role of negative affect on objective verbal memory performance and subjective memory complaints in healthy older adultsJ Int Neuropsychol Soc200814232733618282330

- AlladiSArnoldRMitchellJNestorPJHodgesJRMild cognitive impairment: applicability of research criteria in a memory clinic and characterization of cognitive profilePsychol Med200636450751516426486

- GeerlingsMIJonkerCBouterLMAdèrHJSchmandBAssociation between memory complaints and incident Alzheimer’s disease in elderly people with normal baseline cognitionAm J Psychiatry1999156453153710200730

- JonkerCGeerlingsMISchmandBAre memory complaints predictive for dementia? A review of clinical and population-based studiesInt J Geriatr Psychiatry20001598399111113976

- HanJWKimaTHLeebSBPredictive validity and diagnostic stability of mild cognitive impairment subtypesAlzheimers Dement2012855355923102125