Abstract

Background

Musculoskeletal conditions and insufficient physical activity have substantial personal and economic costs among contemporary aging societies. This study examined the age distribution, comorbid health conditions, body mass index (BMI), self-reported physical activity levels, and health-related quality of life of patients accessing ambulatory hospital clinics for musculoskeletal disorders. The study also investigated whether comorbidity, BMI, and self-reported physical activity were associated with patients’ health-related quality of life after adjusting for age as a potential confounder.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was undertaken in three ambulatory hospital clinics for musculoskeletal disorders. Participants (n=224) reported their reason for referral, age, comorbid health conditions, BMI, physical activity levels (Active Australia Survey), and health-related quality of life (EQ-5D). Descriptive statistics and linear modeling were used to examine the associations between age, comorbidity, BMI, intensity and duration of physical activity, and health-related quality of life.

Results

The majority of patients (n=115, 51.3%) reported two or more comorbidities. In addition to other musculoskeletal conditions, common comorbidities included depression (n=41, 18.3%), hypertension (n=40, 17.9%), and diabetes (n=39, 17.4%). Approximately one-half of participants (n=110, 49.1%) self-reported insufficient physical activity to meet minimum recommended guidelines and 150 (67.0%) were overweight (n=56, 23.2%), obese (n=64, 28.6%), severely obese (n=16, 7.1%), or very severely obese (n=14, 6.3%), with a higher proportion of older patients affected. A generalized linear model indicated that, after adjusting for age, self-reported physical activity was positively associated (z=4.22, P<0.001), and comorbidities were negatively associated (z=−2.67, P<0.01) with patients’ health-related quality of life.

Conclusion

Older patients were more frequently affected by undesirable clinical attributes of comorbidity, obesity, and physical inactivity. However, findings from this investigation are compelling for the care of patients of all ages. Potential integration of physical activity behavior change or other effective lifestyle interventions into models of care for patients with musculoskeletal disorders is worthy of further investigation.

Introduction

The increasing prevalence, health burden, and economic cost of chronic musculoskeletal disorders over recent decades have resulted in their identification as a key health concern for contemporary aging societies.Citation1–Citation7 The estimated economic cost of musculoskeletal disorders in the United States was 7.4% of the nation’s gross domestic product, or approaching $950 billion annually (2006).Citation8 In addition, concerning personal and economic costs of musculoskeletal disorders have been reported among other nations.Citation5–Citation7,Citation9,Citation10 This has occurred while the proportion of the population meeting minimum recommended physical activity guidelines has decreased, and child and adult obesity levels have increased internationally.Citation11–Citation20

Empirical evidence suggests that the increasing burden of chronic musculoskeletal disorders among increasingly sedentary populations is not a coincidence.Citation21–Citation26 Musculoskeletal disorders are prevalent among sedentary populations, even though insufficient physical activity is a modifiable risk factor for premature mortality.Citation27–Citation33 Insufficient physical activity is associated with a range of negative health outcomes that can have increasing prevalence with aging, including heart disease, diabetes, and musculoskeletal disorders, as well as depression.Citation31,Citation33–Citation35 The World Health Organization has identified physical inactivity as the fourth leading risk factor for mortality globally.Citation27 In addition to negative personal health impacts, physical inactivity places a heavy financial burden on economies worldwide. For example, the annual cost of physical inactivity to the United States economy was estimated at US$13.8 billion in 2008.Citation36 Despite Australia having a much smaller population than the United States, the cost of physical inactivity to the Australian health care system in 2007 was an avoidable AU$1.5 billion per year,Citation37 representing a substantial economic burden to the Australian society and demonstrating that this problem is not isolated by geographical region.

There are a range of benefits associated with increasing physical activity. Immediate gains include improved musculoskeletal and mental health as well as cardiovascular and respiratory benefits.Citation31,Citation38 Medium- and longer-term benefits are wide-ranging.Citation28–Citation35 Physical activity may reduce the severity of existing health conditions and prevent a range of further comorbidities.Citation28–Citation35 Increasing or maintaining physical activity levels and physical functioning can also reduce the risk of being impacted by physical debility and falls associated with aging.Citation39–Citation42

From a health service perspective, people with musculoskeletal disorders are an important clinical group that are likely to benefit from physical activity, but who may require additional support to become physically active.Citation34,Citation35 Musculoskeletal disorders cause pain and contribute to reduced mobility and impaired health-related quality of life.Citation35,Citation43 Chronic musculoskeletal disorders and physical inactivity have been associated with other conditions, such as obesity and depression.Citation34 The interaction between patients and health professionals in clinical settings may prove a useful opportunity to link inactive patients with positive physical activity behavior change interventions.Citation44 While it is likely that people accessing ambulatory clinical services for nonsurgical treatment of musculoskeletal disorders would obtain health benefits from increasing their physical activity levels, a range of important research questions in this field currently remain unanswered. For potential investment in physical activity behavior change interventions to be justified and appropriately targeted in these clinical settings, it is important to understand the health profile of patients accessing these services.

This investigation had three objectives to be investigated among people receiving nonsurgical interventions for musculoskeletal conditions affecting any body region. The first objective was to examine the age distribution, comorbid health conditions, body mass index (BMI), and self-reported physical activity levels among patients accessing (nonsurgical) ambulatory hospital clinics for musculoskeletal disorders. The second objective was to describe the health-related quality of life profile of this sample. The third objective was to investigate whether comorbidity, BMI, and self-reported physical activity were associated with patients’ overall health-related quality of life (after adjusting for age as a potential confounder).

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional survey investigation utilizing a custom-designed quantitative questionnaire (including standardized self-reported measures of physical activity and health-related quality of life) at a single assessment point was undertaken.

Participants and setting

A total of 296 community-dwelling adult patients accessing ambulatory hospital services for nonsurgical treatment of one or more musculoskeletal disorders were invited to participate between January and March 2012. This was a convenience cross-sectional sample of patients accessing the participating clinics. An additional 1-month post-recruitment closure period was permitted for the return of any questionnaires that had been completed but not yet returned. The ambulatory hospital services included a musculoskeletal physical therapy outpatient clinic, a multidisciplinary (physical therapy, nutrition and dietetics, psychology, occupational therapy) service for spinal pain, and a musculoskeletal outpatient aquatic physical therapy clinic. These clinics were selected because they included a broad cross-section of community-dwelling individuals with musculoskeletal conditions receiving conservative (nonsurgical) interventions.

It is usual practice for patients attending these clinics to receive therapy programs according to their individual musculoskeletal condition and other circumstances, including their response to initial treatment and perceived potential to receive benefit from further intervention. The volume of intervention and frequency of clinic appointments are not rigidly predetermined according to the type of referral or presenting condition. Participation in this study did not affect patients’ routine clinical care, and the amount of therapy that individuals received (before or after completing the questionnaire) was not within the scope of this investigation.

Ethics statement

This investigation was approved by the Metro South Health (Brisbane, QLD, Australia) Research Ethics Committee and the Queensland University of Technology (Brisbane, QLD, Australia) Human Research Ethics Committee. Participation or nonparticipation in this research investigation were voluntary and did not influence the care offered to or received by patients. Patients provided informed consent before participation in the study.

Outcomes

The questionnaire contained items about demographic and clinical information including age; sex; weight and height (used to calculate BMI); primary reason for referral to the clinic; comorbid health conditions; self-reported physical activity levels (measured with the Active Australia SurveyCitation45); and health-related quality of life, measured with the EQ-5D instrument.Citation46

The Active Australia Survey required participants to report the number of weekly occurrences and total duration of: continuous walking for at least 10 minutes; vigorous gardening or heavy work around the yard; vigorous physical activity (for example, jogging or cycling); and other moderate physical activities (for example, swimming or social tennis).Citation45 The number and duration of activities reported may include any type of physical activity. The physical activity reported is classified into walking, moderate activity, or vigorous activity, including duration and number of activities per week in each of the categories.Citation45 For determining whether a respondent was sufficiently physically active to meet minimum recommended guidelines for health benefits, time spent undertaking vigorous activity was assigned a double weighting.Citation45 Sufficient physical activity is calculated as the accumulation of at least five sessions and 150 minutes of moderate physical activity (or equivalent vigorous activity) per week.Citation45 This instrument was developed and validated as part of an Australian government initiative to assist in the collection of standardized data for physical activity measurement among Australian adults.Citation45 The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare established an expert working group on physical activity measurement to develop the questionnaire content.Citation45 This group examined the issues surrounding measurement of physical activity, reviewed existing physical activity measures, and undertook related research and consultation before identifying data elements necessary for physical activity measurement.Citation45 The Active Australia Survey has been used in nationwide and state-based government surveys in Australia and has exhibited good reliability, face validity, criterion validity, and respondent acceptability.Citation45,Citation47

The EQ-5D is among the most widely used instruments internationally for the evaluation of health-related quality of life among older adults in clinical and research settings.Citation46–Citation52 This generic health-related quality of life questionnaire includes the five domains of mobility, personal care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. In each domain, respondents indicate that they experience no problems, some/moderate problems, or extreme problems/inability. The instrument also includes a 101-point vertical visual analog scale (EQ-VAS), where 0 (0 cm) and 100 (20 cm) represent the worst and best imaginable health state, respectively.Citation46 Responses from the five domains can be converted to a single summary score, where death and full health are represented by 0.00 and 1.00, respectively;Citation53,Citation54 this is known as a multi-attribute utility score. The EQ-5D has demonstrated favorable validity,Citation49–Citation52,Citation55,Citation56 reliability,Citation48–Citation51 and responsivenessCitation49,Citation51,Citation52,Citation57 across a range of adult populations.Citation48–Citation52,Citation55–Citation57

The investigators considered it plausible that some inaccuracies may be present using self-report questionnaires (particularly for physical activity levels) in comparison to objective monitoring or a suite of clinical tests for common conditions. However, the decision to select the aforementioned outcome measures for this investigation was guided by several factors. First, survey completion had the pragmatic advantage of being more efficient and less invasive than pathology testing or objective physical activity monitoring, which would likely have yielded a lower participation rate and higher chance of sampling bias than questionnaire-based assessments. Second, the aforementioned instruments permitted the investigators to consider whether data from this sample were consistent with (or in contrast to) population norms.Citation58 Finally, the use of these questionnaires was consistent with the way assessments are ordinarily conducted in the participating clinics, meaning that findings from this investigation would likely reflect those observed by clinical staff working in these settings who may act as potential gatekeepers for the initiation of lifestyle-related behavior change interventions.

Procedure

Clinic attendees were asked by a usual clinic staff member whether or not they would be interested in finding out about participation in the study. Those who were interested were subsequently contacted by a research assistant who provided a study information sheet, consent form, and questionnaire. This research assistant also addressed any questions potential participants had with regard to participation in the study. To maximize the response rate, potential respondents were instructed that they could either self-complete the survey then return it to a confidential sealed box located at the clinic administration desk at a subsequent appointment (or via post); read the responses over the telephone to a member of the research team who would call them 1 week after receiving the survey; or directly enter their responses onto a web-based version of the questionnaire via the internet (a web address was provided with the study information; additionally, four participants requested and were sent the link via email).

Analysis

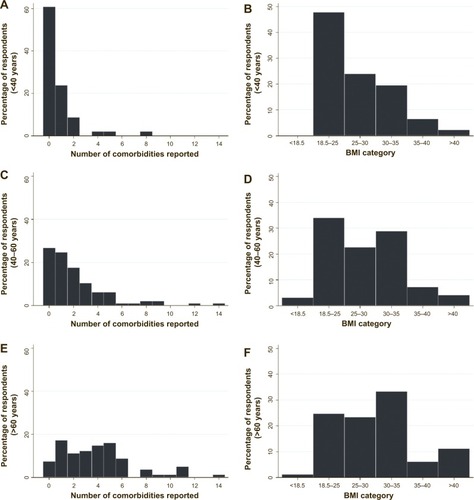

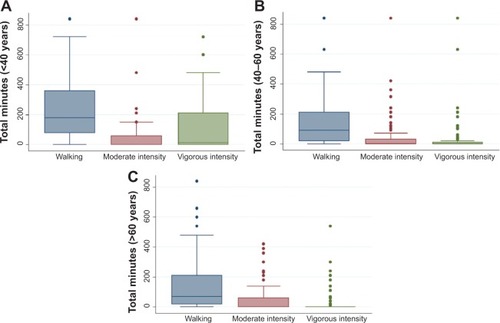

Analyses were conducted using Stata/IC software (v 11.2; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics and figures were prepared to examine the age distribution, comorbid health conditions, BMI, and self-reported physical activity levels of the sample. Specifically, to examine the age distribution of respondents, a frequency histogram was prepared; the mean (and standard deviation [SD]) age was also calculated. In addition, a plot of the quantiles for patient age versus the quantiles of a normal distribution was also prepared (Q–Q plot), but this did not suggest that substantial deviation from a normal distribution was present (plot not displayed). For the purpose of subsequent descriptive analyses, the sample were categorized into a younger age group (<40 years), middle age group (40–60 years), and older age group (>60 years). The primary reasons for referral to the clinics and frequency of comorbid health conditions were tabulated for each age grouping. Frequency histograms were prepared to display the number of comorbid conditions present and BMI for each age group. BMIs were calculated as body mass in kilograms divided by the square of body height in meters and were categorized according to guidelines set out by the World Health Organization.Citation59 Self-reported physical activity durations and intensities were presented in box plots.

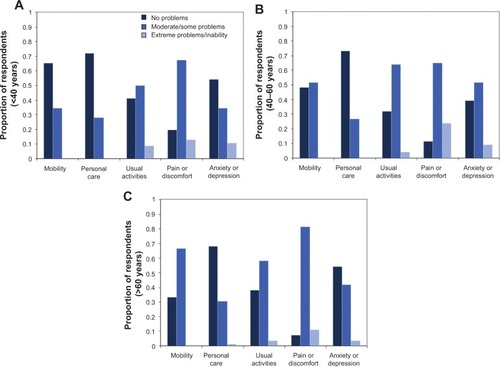

To describe the health-related quality of life profile of this sample, frequency histograms were used to display the distribution of responses across the five health-related quality of life domains for each age group. Dolan’s tariff system was applied to generate multi-attribute utility scores from the EQ-5D, where 0.00 represents death and 1.00 represents full health; health states considered worse than death are assigned a negative score.Citation53 Dolan’s preference-based system was selected as it was derived from a society with similar values to that from which this sample was drawn;Citation53 additionally, it has been widely used in psychometric investigations of the EQ-5D that have reported favorable findings.Citation48–Citation51,Citation55–Citation57 Mean (and SD) EQ-VAS and multi-attribute utility scores were determined for the three age groupings.

To investigate whether comorbidity, BMI, and self-reported physical activity (minutes of moderate intensity equivalent activity per week) were associated with patients overall health-related quality of life after adjusting for age, a generalized linear model was prepared. The generalized linear model (Gaussian family and identity link function) examined the association between the EQ-5D multi-attribute utility score (dependent variable) and the number of comorbid health conditions, BMI category, and (moderate) physical activity equivalent time (independent variables). Due to potential differences in the properties of the independent variables included in the generalized linear model, sensitivity of the model fit to selection of other potential family and link function combinations was performed. This was undertaken by substituting in all other potential family and link functions; similar model fits and the same significant associations were evident regardless of the combination of family and link function selected (only Gaussian family and identity link function presented). Prior to preparing the linear model, a correlation matrix was computed to examine any potential collinearity between the independent variables (as well as age as a potential confounder). All combinations of associations between the independent variables were weak at most (all rho <0.40). Age had a moderate association with number of comorbidities (rho =0.44) and weaker associations with physical activity time (rho =−0.33) and BMI (rho =0.22), supporting the inclusion of age as a potential confounding variable. To account for potential uncertainty in the nature of probability distribution for the observed coefficients from the generalized linear model, 95% confidence intervals for the coefficients were generated using bootstrap resampling (2,000 replications, bias corrected and accelerated to adjust for any potential bias or skewness in the bootstrap distribution).

Results

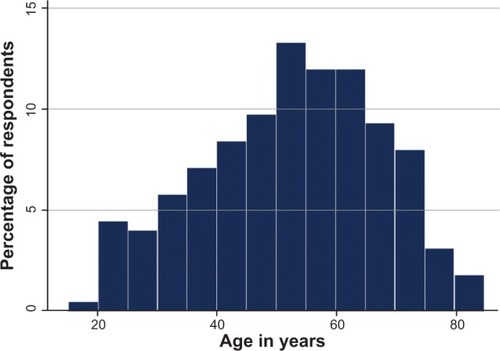

A total of 224 (76%) potential participants completed the survey. This included responses read to a research assistant over the telephone (n=203, 90.6%), those given online (n=5, 2.2%), and those in hard copy returned to the patient’s clinic (n=16, 7.1%). The primary reasons for referral to the participating clinics are displayed in . Back condition was the most frequently reported primary reason for referral across all ages (total n=84, 37.5%). Overall, 117 (52.2%) respondents were male. The age of patients approximated a normal distribution (), with the mean (SD) age being 53 (15) years. The youngest and oldest participants were 18 and 84, respectively.

Table 1 Primary reasons for respondent referrals to the participating clinics (n=224)

Figure 1 Age distribution of patients accessing ambulatory hospital clinics for musculoskeletal disorders.

Respondents reported a range of comorbid health conditions (), including a range of musculoskeletal disorders in addition to their primary reason for referral. Other common comorbid conditions included depression (n=41, 18.3%), hypertension (n=40, 17.9%), and diabetes (n=39, 17.4%). The majority of patients (n=115, 51.3%) reported two or more comorbidities in addition to their primary reason for attending the clinic. The minimum and maximum number of comorbidities reported was 0 and 14, respectively. The number of comorbid conditions reported by respondents in each age group is presented in , alongside the distribution of BMI for the sample. The overall pattern indicated increased comorbidity and obesity with age among this clinical sample. This was also consistent with the pattern of physical activity reported across the three age groups (), with less physical activity time (particularly vigorous activity time) reported by patients in the older age groups. The median (interquartile range) numbers of reported physical activity sessions of at least 10 minutes’ duration were 8 (4–14) for respondents <40 years, 6 (3–9) for respondents aged 40–60 years, and 5 (3–9) for respondents aged >60 years. Overall, the amount of physical activity reported by 114 (50.9%) respondents exceeded the minimum recommendations for health.

Table 2 Frequency (percentage) of comorbid health conditions self-reported by respondents in addition to their primary reason for clinic attendance

Figure 2 Number of comorbidities and percentage of respondents in each body mass index (BMI) category.

Notes: Number of comorbidities and BMI of patients aged <40 years (A and B), 40–60 years (C and D), and >60 years (E and F).

Figure 3 Physical activity among respondents.

The mean and SD multi-attribute utility scores derived from the EQ-5D instrument (0.562, SD =0.298) and EQ-VAS score (63.3, SD =19.5) were not high relative to the possible scale range, indicating that impairments in health-related quality of life were prevalent in this clinical population. Health-related quality of life reported across the EQ-5D domains are displayed in . Deficits were frequently reported across all five domains, with pain and discomfort the most frequently affected domain. A higher proportion of older patients reported problems with mobility than younger patients. Deficits in the domains of usual activities and depression or anxiety were present for substantial proportions of patients across each age group.

Figure 4 Health-related quality of life of respondents.

The linear model examining the association between patients’ health-related quality of life (expressed as multi-attribute utility) and their comorbid health conditions, BMI, and physical activity time (with age as a potential confounder) is displayed in . In summary, physical activity was positively associated and comorbidities were negatively associated with patients’ health-related quality of life. BMI was not associated with health-related quality of life in this model. The coefficients from this model () indicated that even modest differences in the physical activity and comorbidities variables were associated with a potential minimal clinically important difference of 0.03Citation60 in (health-related quality of life) utility score. For example, the coefficients in this model indicated that 2 hours of moderate physical activity per week, or 1 hour of vigorous physical activity per week, may be associated with a >0.03 higher utility score. Each comorbidity was associated with a 0.022 lower utility score.

Table 3 Summary of coefficients (and bootstrap-generated confidence intervals), z-scores, and P-values from the generalized linear model examining the association between multi-attribute utility and number of comorbidities, body mass index, physical activity time, and age

Discussion

This investigation has suggested a large proportion of the patients accessing ambulatory clinics for musculoskeletal conditions were overweight or obese, had multiple chronic comorbid health conditions, and were physically inactive. The frequency of these undesirable clinical characteristics was higher among older patients than younger patients. Subsequently, patients frequently reported substantially impaired health-related quality of life associated with comorbidity and (lack of) physical activity. It is noteworthy that approximately one-half of the participants in this study self-reported physical activity levels that did not meet minimum recommended guidelines to experience health benefits associated with regular physical exercise. Given the other clinical characteristics of the sample (primary reasons for referral, BMI distribution, and comorbidities), and the propensity for some individuals to overestimate or overreport their physical activity when using self-reported measures, it is likely that this may be a conservative estimate of the proportion of patients who are insufficiently physically active for health benefits.Citation61

The proportion of participants in this sample who were obese or severely obese was approximately double that of the wider Australian population.Citation58 The high numbers of self-reported musculoskeletal disorders among this clinical group were expected. However, the rates of other chronic health conditions were concerning; these included frequent reports of depression, hypertension, and diabetes – conditions that may be ameliorated with physical activity. It is noteworthy that several of these common comorbid conditions are strong risk factors for the development of further severe health conditions including heart disease and stroke.Citation62 The proportion of this sample that reported difficulty in health-related quality of life domains captured by the EQ-5D instrument were between two and seven times higher than those reported by the wider population.Citation63 While the purpose of this investigation was not to develop a comprehensive model of health-related quality of life correlates, the study did achieve an important objective in identifying that physical activity and number of comorbidities were associated with health-related quality of life, even after adjustment for age as a covariate.

These findings support further consideration of the potential integration of effective lifestyle behavior change interventions into clinical services, including general physical activity and dietary interventions. Assisting inactive and overweight patients to improve their health profile through better health-related behaviors may not only be beneficial for their presenting condition, but assist in the prevention or long-term management of other common chronic conditions that are present in this population. However, given that some types of physical activity may be inappropriate for people with certain musculoskeletal conditions, and that concurrent comorbidities (including depression) are prevalent in this clinical group, it is perhaps important that appropriately qualified health professionals have a direct role in the provision of advice and support for patients in this clinical setting. This may include the use of tailored physical activity programs suitable for the nature of the patient’s condition and level of motivation.

The discrepancy between BMI and self-reported obesity as a health condition was also of interest. Only 22 (9.8%) participants across all ages self-reported obesity as a health condition they had (). This is in contrast to the 94 (42.0%) who reported their height and weight corresponding with a BMI value exceeding 30. This discrepancy may be attributable to those with a BMI exceeding 30 either not considering themselves to be obese or not wanting to identify obesity as a health condition that they have. This underestimation of obesity may have implications both for the clinical management of musculoskeletal conditions associated with having excess body mass, as well as for motivation to make lifestyle-related changes, including to physical activity and dietary behaviors. This finding of self-underestimation of obesity is consistent with previous population-based investigations among adult and youth samples,Citation64,Citation65 and has previously been considered an impediment to associated nutritional lifestyle behavior change interventions for weight loss.Citation65

This investigation had several methodological strengths as well as factors that limit the ability to extrapolate findings from this investigation. First, the target population for this investigation was specific to those accessing ambulatory hospital clinics for musculoskeletal disorders. It is possible that people with musculoskeletal disorders in dissimilar societies may not have responded in the same way as participants in this investigation. Second, offering participants the option for multiple modes of survey response may be considered both a strength and weakness of this investigation. Permitting multiple ways of returning survey responses may have contributed to the relatively high response rate;Citation66 however, the small proportion of the sample that chose to return their response via the internet or post box located in the clinic prohibited use of inferential statistics to confirm that no differences existed between the response return options. However, the use of standardized instruments within the survey that have demonstrated reliability using multiple administration modalities could be considered a strength.Citation45,Citation48–Citation51 Third, the survey was self-reported. There is some evidence that people may overreport their physical activity level, as well as underreport their weight and overestimate their height for BMI calculations when completing self-report measures.Citation61,Citation67 So, while this self-report survey appropriately addressed the research objectives and potentially enhanced the response rate, the findings from this investigation regarding the presence of insufficient physical activity and proportion of the sample that were overweight or obese are likely to be a conservative estimate of the scale of these problems among this clinical population.

These findings have important implications for health care administrators, clinical leaders, practitioners, and researchers in this field. The finding of multiple health conditions, obesity, other musculoskeletal disorders, and impaired health-related quality of life is concerning, but not surprising, among this clinical group who were frequently physically inactive. Inactive patients who consume more dietary calories than they expend will likely continue to experience further negative consequences associated with physical inactivity and excessive caloric intake. They are more likely to develop additional chronic health conditions and die prematurely.Citation27–Citation33 Conversely, increasing their physical activity to recommended levels would likely promote a variety of health benefits, including reduced risk of death due to heart disease or stroke.Citation29,Citation30 In addition to reducing the risk of mortality, increasing physical activity levels among this group would likely result in reduced morbidity associated with the musculoskeletal disorders for which they are receiving treatment and other conditions associated with sedentary lifestyles.Citation28,Citation31–Citation35 Successfully promoting appropriate dietary intake could also yield a wide range of associated health benefits.Citation68

The point of interaction between people with musculoskeletal disorders and health services offers an excellent opportunity to initiate transition to healthier lifestyles among this population. People currently accessing health services frequently only receive treatment for their primary diagnosis, with cursory attention given to lifestyle-related behaviors.Citation69 The lack of provision of any personalized intervention, such as interventions addressing physical inactivity or dietary intake, is a missed opportunity.Citation69 However, the presence of comorbidities, pain, and reduced mobility has implications for potential efforts to address the problem of physical inactivity in this population who may have difficulty undertaking conventional exercise. Unfortunately, there is currently a scarcity of research investigating lifestyle-related interventions specifically among people with musculoskeletal disorders, particularly among older adults. One proposed solution is to use the point of interaction between health professionals and inactive patients as a conduit to connect these patients with a targeted physical activity behavior change intervention that is suitable for their current health state and age.Citation44 In the context of ambulatory musculoskeletal clinics, this is likely to involve guidance from the treating clinical experts regarding the types of physical activity suitable for each patient being referred for a physical activity intervention.

There are a number of priorities for future research to improve the health profile of patients of all ages with musculoskeletal disorders. Health professionals involved in the care of this clinical group may provide insight for the development of targeted lifestyle-related interventions and their integration into clinical settings. This insight may include the likely barriers and facilitators that patients may face when attempting to undertake physical activity, as well as pragmatic factors associated with the delivery of lifestyle interventions.Citation44 Similarly, patients are also likely to be a valuable source of information regarding obstacles to altering their lifestyle and preferences for receiving support from health services. In addition to the development of interventions informed by patients and health professionals, the method by which these interventions are delivered is also worthy of consideration.Citation44 For example, time pressures within existing clinical settings may necessitate the need for lifestyle interventions to be initiated within the clinical setting but with further support delivered remotely via the use of contemporary communication technologies.Citation44 Successful behavior change interventions to improve the health profile of patients with musculoskeletal disorders will likely not only reduce patients’ morbidity and mortality, but reduce the demand on health services and economic costs associated with future health care delivery.

Conclusion

Older patients were more frequently affected by undesirable clinical attributes of comorbidity, obesity, and physical inactivity than younger patients. These negative attributes were associated with impairment to patients’ health-related quality of life. Findings from this investigation are compelling not only for the care of older patients accessing these clinical services, but for patients of all ages, with many younger patients also reporting negative clinical characteristics and impaired health-related quality of life. Potential integration of physical activity behavior change or other effective lifestyle interventions into models of care for patients with musculoskeletal disorders is worthy of further investigation.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CôtéPvan der VeldeGCassidyJDBone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated DisordersThe burden and determinants of neck pain in workers: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated DisordersSpine (Phila Pa 1976)2008334 SupplS60S7418204402

- ParkerLNazarianLNCarrinoJAMusculoskeletal imaging: medicare use, costs, and potential for cost substitutionJ Am Coll Radiol20085318218818312965

- PraemerAFurnerSRiceDPAmerican Academy of Orthopaedic SurgeonsMusculoskeletal Conditions in the United StatesPark Ridge, ILAmerican Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons1992

- StewartWFRicciJACheeEMorgansteinDLiptonRLost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforceJAMA2003290182443245414612481

- van TulderMWKoesBWBouterLMA cost-of-illness study of back pain in The NetherlandsPain19956222332408545149

- WoolfADPflegerBBurden of major musculoskeletal conditionsBull World Health Organ200381964665614710506

- YelinECost of musculoskeletal diseases: impact of work disability and functional declineJ Rheumatol Suppl20036881114712615

- American Academy of Orthopaedic SurgeonsThe Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States: Prevalence, Societal and Economic Cost2nd edPark Ridge, ILAmerican Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons2011

- CoytePCAscheCVCroxfordRChanBThe economic cost of musculoskeletal disorders in CanadaArthritis Care Res19981153153259830876

- AIHWBeggSVosTBarkerBStevensonCStanleyLLopezA2007The burden of disease and injury in Australia 2003. Cat. no. PHE 82CanberraAIHW Available from http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442467990Accessed February 7, 2013

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)Prevalence of leisure-time and occupational physical activity among employed adults – United States, 1990MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep2000491942042410905821

- BorehamCRiddochCThe physical activity, fitness and health of childrenJ Sports Sci2001191291592911820686

- CameronAJDunstanDWOwenNHealth and mortality consequences of abdominal obesity: evidence from the AusDiab studyMed J Aust2009191420220819705980

- CameronAJWelbornTAZimmetPZOverweight and obesity in Australia: the 1999–2000 Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab)Med J Aust2003178942743212720507

- CecchiniMSassiFLauerJALeeYYGuajardo-BarronVChisholmDTackling of unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and obesity: health effects and cost-effectivenessLancet201037697541775178421074255

- DuganSAExercise for preventing childhood obesityPhys Med Rehabil Clin N Am2008192205216vii18395644

- PanWHLeeMSChuangSYLinYCFuMLObesity pandemic, correlated factors and guidelines to define, screen and manage obesity in TaiwanObes Rev20089Suppl 1223118307695

- TrakasKOhPISinghSRisebroughNShearNHThe health status of obese individuals in CanadaInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord200125566266811360148

- WakeMBaurLAGernerBOutcomes and costs of primary care surveillance and intervention for overweight or obese children: the LEAP 2 randomised controlled trialBMJ2009339b330819729418

- [No authors listed]Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultationWorld Health Organ Tech Rep Ser2000894ixii125311234459

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)State-specific prevalence of no leisure-time physical activity among adults with and without doctor-diagnosed arthritis – United States, 2009MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep201160481641164522157882

- Balboa-CastilloTLeón-MuñozLMGracianiARodríguez-ArtalejoFGuallar-CastillónPLongitudinal association of physical activity and sedentary behavior during leisure time with health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adultsHealth Qual Life Outcomes201194721708011

- Figueiredo NetoEMQueluzTTFreireBFPhysical activity and its association with quality of life in patients with osteoarthritisRev Bras Reumatol2011516544549 English, Portuguese22124589

- LiSHeHDingMHeCThe correlation of osteoporosis to clinical features: a study of 4382 female cases of a hospital cohort with musculoskeletal symptoms in southwest ChinaBMC Musculoskelet Disord20101118320712872

- McBethJNichollBICordingleyLDaviesKAMacfarlaneGJChronic widespread pain predicts physical inactivity: results from the prospective EPIFUND studyEur J Pain201014997297920400346

- MorkenTMagerøyNMoenBEPhysical activity is associated with a low prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in the Royal Norwegian Navy: a cross sectional studyBMC Musculoskelet Disord200785617601352

- Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for HealthGenevaWorld Health Organization2010 Available from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599979_eng.pdfAccessed May 16, 2013

- HuFBSigalRJRich-EdwardsJWWalking compared with vigorous physical activity and risk of type 2 diabetes in women: a prospective studyJAMA1999282151433143910535433

- HuFBStampferMJColditzGAPhysical activity and risk of stroke in womenJAMA2000283222961296710865274

- MansonJEHuFBRich-EdwardsJWA prospective study of walking as compared with vigorous exercise in the prevention of coronary heart disease in womenN Engl J Med1999341965065810460816

- BonnetFIrvingKTerraJLNonyPBerthezèneFMoulinPDepressive symptoms are associated with unhealthy lifestyles in hypertensive patients with the metabolic syndromeJ Hypertens200523361161715716704

- BoothFWGordonSECarlsonCJHamiltonMTWaging war on modern chronic diseases: primary prevention through exercise biologyJ Appl Physiol (1985)200088277478710658050

- ColbergSRAlbrightALBlissmerBJAmerican College of Sports MedicineAmerican Diabetes AssociationExercise and type 2 diabetes: American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Exercise and type 2 diabetesMed Sci Sports Exerc201042122282230321084931

- WarburtonDEGledhillNQuinneyAMusculoskeletal fitness and healthCan J Appl Physiol200126221723711312417

- WarburtonDEGlendhillNQuinneyAThe effects of changes in musculoskeletal fitness on healthCan J Appl Physiol200126216121611312416

- ChenowethDLeutzingerJThe economic cost of physical inactivity and excess weight in American adultsJ Phys Act Health20063148163

- The Cost of Physical Inactivity: What is the Lack of Participation in Physical Activity Costing Australia?Medibank Private2007 Available from: http://www.medibank.com.au/Client/Documents/Pdfs/pyhsical_inactivity.pdfAccessed May 16, 2013

- MartinsonBCO’ConnorPJPronkNPPhysical inactivity and short-term all-cause mortality in adults with chronic diseaseArch Intern Med200116191173118011343440

- HillAMHoffmannTMcPhailSEvaluation of the sustained effect of inpatient falls prevention education and predictors of falls after hospital discharge – follow-up to a randomized controlled trialJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci20116691001101221743091

- HainesTPHillAMHillKDCost effectiveness of patient education for the prevention of falls in hospital: economic evaluation from a randomized controlled trialBMC Med20131113523692953

- HillAMHoffmannTMcPhailSFactors associated with older patients’ engagement in exercise after hospital dischargeArch Phys Med Rehabil20119291395140321878210

- McPhailSBellerEHainesTPhysical function and health-related quality of life of older adults undergoing hospital rehabilitation: how strong is the association?J Am Geriatr Soc201058122435243721143451

- McPhailSMDunstanJCanningJHainesTPLife impact of ankle fractures: qualitative analysis of patient and clinician experiencesBMC Musculoskelet Disord201213122423171034

- McPhailSSchippersMAn evolving perspective on physical activity counselling by medical professionalsBMC Fam Pract20121313122524484

- The Active Australia Survey: A Guide and Manual for Implementation, Analysis and ReportingCanberraAustralian Institute of Health and Welfare2003 Available from http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442467449Accessed October 26, 2011

- RabinRde CharroFEQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol GroupAnn Med200133533734311491192

- McPhailSMWaiteMCPhysical activity and health-related quality of life among physiotherapists: a cross sectional survey in an Australian hospital and health serviceJ Occup Med Toxicol201491124405934

- McPhailSLanePRussellTTelephone reliability of the Frenchay Activity Index and EQ-5D amongst older adultsHealth Qual Life Outcomes200974819476656

- CoonsSJRaoSKeiningerDLHaysRDA comparative review of generic quality-of-life instrumentsPharmacoeconomics2000171133510747763

- FransenMEdmondsJReliability and validity of the EuroQol in patients with osteoarthritis of the kneeRheumatology (Oxford)199938980781310515639

- HurstNPKindPRutaDHunterMStubbingsAMeasuring health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: validity, responsiveness and reliability of EuroQol (EQ-5D)Br J Rheumatol19973655515599189057

- ObradovicMLalALiedgensHValidity and responsiveness of EuroQol-5 dimension (EQ-5D) versus Short Form-6 dimension (SF-6D) questionnaire in chronic painHealth Qual Life Outcomes20131111023815777

- DolanPModeling valuations for EuroQol health statesMed Care19973511109511089366889

- DolanPRobertsJModelling valuations for Eq-5d health states: an alternative model using differences in valuationsMed Care200240544244611961478

- KönigHHUlshöferAGregorMValidation of the EuroQol questionnaire in patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200214111205121512439115

- SchweikertBHahmannHLeidlRValidation of the EuroQol questionnaire in cardiac rehabilitationHeart2006921626715797936

- KrabbePFPeerenboomLLangenhoffBSRuersTJResponsiveness of the generic EQ-5D summary measure compared to the disease-specific EORTC QLQ C-30Qual Life Res20041371247125315473503

- Australian Bureau of StatisticsNational Health Survey: Health Risk FactorsCanberraAustralian Bureau of Statistics2010 Available from http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/4364.02007-2008%20%28Reissue%29?OpenDocumentAccessed December 11, 2012

- [No authors listed]Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert CommitteeWorld Health Organ Tech Rep Ser199585414528594834

- PetrouSHockleyCAn investigation into the empirical validity of the EQ-5D and SF-6D based on hypothetical preferences in a general populationHealth Econ200514111169118915942981

- MontoyeHJKemperHCGSarisWHMWashburnRAMeasuring Physical Activity and Energy ExpenditureChampaign, ILHuman Kinetics1996

- RogerVLGoASLloyd-JonesDMAmerican Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics SubcommitteeHeart disease and stroke statistics – 2011 update: a report from the American Heart AssociationCirculation20111234e18e20921160056

- VineyRNormanRKingMTTime trade-off derived EQ-5D weights for AustraliaValue Health201114692893621914515

- GoodmanEHindenBRKhandelwalSAccuracy of teen and parental reports of obesity and body mass indexPediatrics20001061 Pt 1525810878149

- KuchlerFVariyamJMistakes were made: misperception as a barrier to reducing overweightInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord200327785686112821973

- BaruchYResponse rates in academic studies – a comparative analysisHuman Relations1999524421438

- JefferyRWBias in reported body weight as a function of education, occupation, health and weight concernAddict Behav19962122172228730524

- KraussRMEckelRHHowardBAHA Dietary Guidelines: revision 2000: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart AssociationCirculation2000102182284229911056107

- ØstbyeTYarnallKSKrauseKMPollakKIGradisonMMichenerJLIs there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care?Ann Fam Med20053320921415928223