Abstract

Background

The positive effect of social cohesion on well-being in older adults has been well documented. However, relatively few studies have attempted to understand the mechanisms by which social cohesion influences well-being. The main aim of the current study is to identify social pathways in which social cohesion may contribute to well-being.

Methods

The data for this study (taken from 1,880 older adults, aged 60 years and older) were drawn from a national survey conducted during 2008–2009. The survey employed a two-stage stratified sampling process for data collection. Structural equation modeling was used to test mediating and moderating analyses.

Results

The proposed model documented a good fit to the data (GFI =98; CFI =0.99; RMSEA =0.04). The findings from bootstrap analysis and the Sobel test revealed that the impact of social cohesion on well-being is significantly mediated by social embeddedness (Z=5.62; P<0.001). Finally, the results of a multigroup analysis test showed that social cohesion influences well-being through the social embeddedness mechanism somewhat differently for older men than women.

Conclusion

The findings of this study, in addition to supporting the importance of neighborhood social cohesion for the well-being of older adults, also provide evidence that the impact of social cohesion towards well-being is mediated through the mechanism of social embeddedness.

Introduction

Like other countries, Malaysia has an aging population due to increased life expectancy and decreased fertility rates.Citation1 While the continuing increase in life expectancy represents a triumph of medical, social, and economic advances – and should be a matter for congratulations – it also poses the challenge of maintaining the health and well-being of older adults.Citation2 In light of the emphasis on well-being of older adults, research on factors that can maintain and improve well-being in old age has become of greater importance. Review of the gerontological research shows that most preceding studies have focused on the impact of individual characteristics influencing the well-being of older adults.Citation3 In view of the fact that older adults spend more time in their homes, it is possible to expect that they are influenced by their neighborhood surroundings.Citation2,Citation4

Social cohesion, as the cognitive component of social capital, has been conceptualized as levels of mutual trust, norms of reciprocity, shared values, and solidarity among neighbors.Citation5–Citation7 It has also been described as “the glue that bonds society together, promoting harmony, a sense of community, and a degree of commitment to promoting common good”.Citation8

The findings of previous studies show statistically significant associations between perceived neighborhood social cohesion and higher self-rated health,Citation4,Citation9 lower mortality rate,Citation10,Citation11 and lower levels of depressive symptoms.Citation12–Citation14 However, relatively few studies have attempted to understand mechanisms through which social cohesion could affect well-being. Recent studies have suggested the need to inquire into pathways through which neighborhood social cohesion could influence health and well-being.Citation10,Citation15,Citation16

It is assumed that social cohesion may contribute to higher levels of well-being in older adults through a pathway that leads to higher degrees of social organization, including provision of support to neighbors in times of sickness, and help, which may consequently contribute to better outcomes of well-being.Citation2,Citation15

The main purpose of the present study was to identify social pathways by which social cohesion is related to well-being. In addition – since it has been documented that women (compared with men) tend to maintain more emotionally intimate relationships, provide more social support to others, and are substantially benefited by emotional social support against major depressionCitation17–Citation19 – it was hypothesized that effects of social cohesion on well-being differ between gender. Therefore, further analysis was conducted to determine whether the path coefficients for the relationships between social cohesion to well-being are significantly moderated by gender.

Theoretical model

The influence of neighborhood conditions on health can be classified into three types. The first type is related to the physical characteristics of the environment (eg, environmental pollution), which directly affect the individual health of residents. The next condition – that neighborhood may affect health – pertains to neighborhood socioeconomic conditions, such as community services and facilities, which affect health.Citation15,Citation20 The third condition – which several studies have found significantly to positively contribute to health and well-being – is social condition in the neighborhood. However, relatively few studies have attempted to elucidate the mechanisms through which social condition in the neighborhood affects well-being.

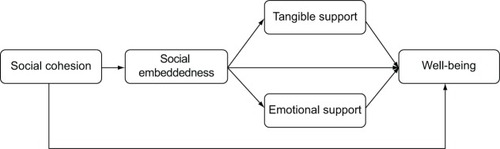

This study aimed to explore social embeddedness as a potential mechanism linking the neighborhood’s social cohesion to well-being. Social embeddedness refers to connections that individuals maintain with other people in their social environment. It is assumed that the presence of social connections ensures that support is being provided.Citation21 A more socially-cohesive neighborhood leads to higher levels of social embeddedness,Citation22,Citation23 thought to lead to supportive interpersonal connections at the individual level (including greater tangible and emotional support), which may contribute to higher levels of well-being.Citation12 shows the proposed theoretical model.

Figure 1 The proposed theoretical model linking social cohesion and well-being.

Based on the proposed theoretical model, the following hypotheses were tested:

Social cohesion is significantly associated with older adults’ well-being.

The social embeddedness mechanism significantly mediates the impact of social cohesion on well-being, through tangible support and emotional support.

The association between social cohesion and well-being is moderated by gender.

Methodology

The data for this study were obtained from a national survey, conducted during 2008–2009, entitled “Patterns of social relationships and psychological well-being among older persons in peninsular Malaysia”.Citation24 The survey employed a two-stage, geographically clustered sampling method to produce a nationally representative sample of older Malaysians. A total of 2,350 households were sampled, with only one older person interviewed from each selected household. Each face-to-face interview was conducted in the respondent’s home. Data were collected on the socioeconomic and health status of adults aged 60 years and older. The completed interviews involved a total of 1,880 older persons, with an overall response rate of 80%. Details of the methodology have been published elsewhere.Citation25

Measures

Social cohesion

Social cohesion was measured using a five-item instrument developed by Sampson et al.Citation26 These items included: 1) People around here are willing to help their neighbors; 2) This is a close-knit neighborhood; 3) People in this neighborhood can be trusted; 4) People in this neighborhood generally do not get along with each other; and 5) People in my neighborhood do not share the same values. The respondents were asked on a five-point scale to score how strongly they agreed with each statement (1= strongly disagree; 5= strongly agree). All five items were added, to produce a total score. Higher total scores indicate that respondents perceive their neighborhood to be more cohesive. In the present study, social cohesion measurement demonstrated very good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha [α] =0.89).

Well-being

The WHO Well-Being Index (WHO-5) – a psychometrically-sound, five-item measure of well-being – was used to assess well-being.Citation27 This instrument has shown good reliability and validity among older Malaysians.Citation25 All five items are rated, based on a six-point Likert scale. The total score is computed from the sum of all five items, and is then transformed into a scale value between 0–100. A higher score indicates higher levels of well-being.Citation28 In the current study, WHO-5 demonstrated very good internal consistency (α=0.87).

Social embeddedness

Social embeddedness has been defined as the frequency of contact with those in one’s social network.Citation21,Citation29 In the current study, social embeddedness was measured by the Lubben Social Network Scale – 6, a six-item, self-reported scale, with a total score range between 0–30. This scale demonstrated an acceptable internal consistency for this sample (α=0.81).

Tangible support

In this study, tangible support was measured using four items taken from the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS).Citation30 These items include: 1) Someone to help you if you were confined to bed; 2) Someone to take you to the doctor if you needed it; 3) Someone to prepare your meals if you were unable to do it yourself; 4) Someone to help with daily chores if you were sick. The total score was obtained from the sum of all four items, and ranges between 1–16. The scale indicated an excellent internal consistency for this study (α=0.93).

Emotional support

Emotional support was measured by averaging respondents’ responses to the four-item scale of emotional/informational support developed in the MOS-SSS.Citation30 These items were as follows: 1) Someone you can count on to listen to you when you need to talk; 2) Someone to confide in or talk to about yourself or your problems; 3) Someone to share your most private worries and fears with; 4) Someone who understands your problems. The total score for emotional support was computed by adding all four items, and ranges between 1–16. Higher scores indicate higher levels of emotional support. This scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current study (α=0.92).

Ethical considerations

The study was ethically conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Malaysia. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all respondents, after explanation of the study’s objectives.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, and zero-order correlations between measurement variables were analyzed using SPSS version 21 statistical software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Structural equation modeling (SEM), using SPSS Amos version 21 software (IBM Corporation), was performed to test the mediation model. The overall model fit was examined using the chi-square test (χ2), comparative fix index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A bootstrapping method was used to test statistical significance of mediation with all mediators in the model.Citation31 The Sobel testCitation32 was also used to make conclusions about the statistical significance of individual mediators. Finally, a multigroup analysis was performed to examine whether the mediation model is moderated by gender.

Results

The mean age of the respondents was 69.79 years (standard deviation: 7.36 years); 52.6% were female and 56.2% were married. presents means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations between measurement variables. As expected, social cohesion was significantly associated with social embeddedness (r[1880]=0.24; P<0.01). In addition, social embeddedness was significantly contributed to tangible support (r[1880]=0.16; P<0.01) and emotional support (r[1880]=0.29; P<0.01). Statistically significant positive associations were also found between well-being and social cohesion (r[1880]=0.24; P<0.01) and social embeddedness (r[1880]=0.25; P<0.01).

Table 1 Means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations between study variables

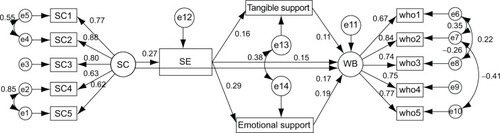

shows the structural equations model used to test the proposed mediational model. The model fit was evaluated using maximum likelihood estimation. Testing the model yielded a good fit to the data (χ2/degree of freedom [df] =5.75; GFI =0.98; CFI =0.98; RMSEA =0.05; PCLOSE =0.45). Factor loadings on the construct of social cohesion ranged from 0.62–0.88. Factor loadings on the construct of well-being ranged from 0.67–0.84, which indicated that the constructs were relatively well-defined. Regarding the processes connecting social cohesion to well-being, the study proposed that social embeddedness significantly mediates the effect of social cohesion upon well-being through two pathways. It was hypothesized that social cohesion leads to increased social embeddedness, which may contribute to inducing tangible support and emotional support, which consequently affect well-being. As shown in , the SEM findings revealed that social cohesion is significantly associated with social embeddedness (critical ratio [CR] =10.45; P<0.001). It was also found that social embeddedness is significantly contributed to tangible support and emotional support. Consequently, tangible support (CR =4.37; P<0.001) and emotional support (CR =7.31; P<0.001) were significantly associated with well-being. The total effect of social cohesion on well-being, which includes both mediating and direct effects, was significant (β=0.23; P<0.001). The mediated effect of social cohesion, through social embeddedness, on well-being was found to be 0.06. This indicates that slightly more than one-fourth of the total effect of social cohesion on well-being is mediated through social embeddedness. Additionally, about 32% of the total effect of social embeddedness on well-being was mediated by tangible support and emotional support (β=0.22; P<0.001).

Table 2 The results of SEM

Table 3 Summary of multigroup analysis

Figure 2 SEM model with standardized regression weights.

Abbreviations: SEM, structural equation modeling; SC, social cohesion; SE, social embeddedness; WB, well-being; CMIN/DF, minimum discrepancy divided by degrees of freedom; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; PCLOSE, p-value for test of close fit; GFI, goodness of fit index; AGFI, adjusted goodness of fit index; CFI, comparative fix index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis coefficient.

In the next step of analysis, a bootstrapping method was used to make conclusions about the significance of indirect effects of social cohesion through social embeddedness, tangible support, and emotional support towards well-being. The finding of the bootstrapping analysis revealed that the impact of social cohesion is significantly mediated by social embeddedness (P<0.001). In addition, tangible support and emotional support also significantly mediated the effect of social embeddedness on well-being (P<0.001). Finally the Sobel test confirmed that social embeddedness significantly mediated the effect of social cohesion on well-being (Z=5.62; P<0.001). In addition, results of other Sobel tests indicated that the effect of social embeddedness is mediated by tangible support (Z=3.58; P<0.001) and emotional support (Z=6.78; P<0.001).

Moderating effect of gender

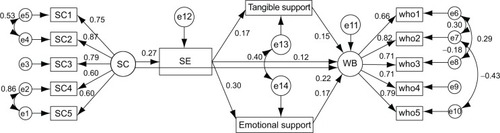

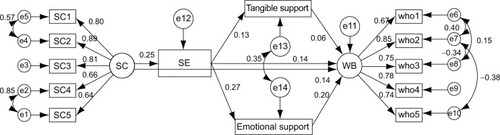

Finally, following Byrne’s guidelines,Citation33 a multigroup analysis test of the full mediation model was conducted, to determine whether the path coefficient for the relationships between social cohesion and well-being were equal in both groups (ie, older men and women). Using SPSS Amos software, the multigroup option was employed, to determine any significant differences in structural parameters between older males and older females. The first step of the analysis involved testing the baseline model for the two groups. Therefore, the validated structural path model was examined across two groups (older men and women) considered collectively – without any equality-constrained relationship across two groups. and show the tested model, indicating good fit between the data and the model (χ2 =383.21; P<0.001; df =108, χ2/df =3.55; GFI =0.97; CFI =0.98; RMSEA =0.037, PCLOSE =1.00). The chi-square and degree of freedom yielded from the unconstrained model were compared to the particular constrained path. The result of the chi-square difference comparison provided significant difference between male and female groups in the relationship between social cohesion and well-being, suggesting that social cohesion affects well-being through a social embeddedness mechanism differently, according to gender.

Figure 3 SEM model with standardized regression weights for male respondents.

Notes: CMIN/DF =3.548; RMSEA =0.037; PCLOSE =1.000; GFI =0.970; AGFI =0.949; CFI =0.980; TLI =0.970.

Abbreviations: SEM, structural equation modeling; SC, social cohesion; SE, social embeddedness; WB, well-being; CMIN/DF, minimum discrepancy divided by degrees of freedom; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; PCLOSE, p-value for test of close fit; GFI, goodness of fit index; AGFI, adjusted goodness of fit index; CFI, comparative fix index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis coefficient.

Figure 4 SEM model with standardized regression weights for female respondents.

Abbreviations: SEM, structural equation modeling; SC, social cohesion; SE, social embeddedness; WB, well-being; CMIN/DF, minimum discrepancy divided by degrees of freedom; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; PCLOSE, p-value for test of close fit; GFI, goodness of fit index; AGFI, adjusted goodness of fit index; CFI, comparative fix index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis coefficient.

Discussion

Findings from the current population-based study are in accordance with a growing body of literatureCitation2,Citation9,Citation11,Citation34 that supports the importance of neighborhood social cohesion for the well-being of older adults. In other words, this result supports the notion that enhancing well-being in older adults should not only rely on improvement of the individuals’ characteristics, but should also consider the contexts of the social environment.Citation4,Citation23,Citation35,Citation36

Regarding the most important goal of this paper – to elucidate how social cohesion may affect well-being of older adults – a theoretical model was proposed and tested. The findings showed that the impact of social cohesion is significantly mediated through a social embeddedness mechanism, wherein social cohesion significantly affects social embeddedness and consequently affects well-being through tangible support and emotional support. This study’s findings supported the proposed theoretical model, which speculated that the socially-cohesive neighborhood might lead to a tightly-knit community, which would increase supportive relations. Increased supportive relations induce more tangible and emotional support, which results in greater well-being. The findings showed that social cohesion leads to higher degrees of social embeddedness, resulting in the provision of higher levels of tangible support and emotional support to neighbors, in times of sickness and for help with household tasks. Consequently, it results in greater levels of well-being in older adults.

The third hypothesis – which postulated that the association between social cohesion and well-being is moderated by gender – was supported. The finding of the multigroup analysis showed that a social embeddedness mechanism mediates the impact of social cohesion on well-being through two pathways: tangible support and emotional support, which differ for men and women. According to the social embeddedness mechanism, social cohesion mostly contributes to greater levels of well-being in men through tangible support. However, for women, the positive impact of social cohesion on well-being is substantially mediated through emotional support. These findings are in line with some previous studies, which have found that the association between social support and health status differs according to gender.Citation37,Citation38 Our findings are also supported by studies that highlight the more important role of emotional support towards well-being and health in older women than in men.Citation17,Citation39 Moreover, it was found that the mediating effect of tangible support on the association between social cohesion and well-being was considerably greater among men. This finding is consistent with the results of studies that show the more important role of tangible support toward health for men than for women.Citation40 Older men (compared to women) are more likely to benefit from tangible support, whereas older women gain advantage through emotional support from their social environment. This premise is supported by studies which found that older men were at risk of experiencing unmet needs when there is a lack of tangible support for their physical care.Citation41 However, among older women, greater levels of emotional support are found to be important in reducing depression and boosting psychological well-being.Citation17,Citation39 This study adds that increased social embeddedness resulting from social cohesion induces more tangible support for men and emotional support for women. Additionally, this finding is in agreement with the finding of Wellman and Wortley: that men are unlikely to get emotional support from friends, and that they rely on family, rather than friends, to obtain emotional support.Citation42

Limitations of the study

Although the results of the present study provide useful information, there are some limitations which deserve attention. First, the most serious limitation of the study is its reliance on cross-sectional design. Consequently, the possibility that greater levels of well-being cause older adults to have more interaction with others and perceive their neighbors in a more positive light cannot be ruled out. Therefore, future use of longitudinal studies is needed to confirm the proposed model. The second limitation to be addressed is the use of a self-reporting method for data gathering, which may result in response bias.Citation43 Since some methodological texts suggest the importance of using longitudinal data for mediation analysis, to avoid model bias,Citation44,Citation45 the final concern that should be addressed is the use of cross-sectional data for mediation analysis. However, it is important to mention that mediation analysis can also be conducted using cross-sectional observations.Citation46,Citation47

Conclusion

In this study, social embeddedness was theorized as a potential mechanism linking neighborhood social cohesion to well-being. In addition to highlighting the importance of social cohesion in neighborhoods for the well-being of older adults, the current study provides evidence to support the function of social embeddedness as a mechanism, linking social cohesion to well-being through tangible and emotional supports. Therefore, social and health policymakers should design and implement interventions, such as revitalizing neighborhoodsCitation48 and developing interventions curriculums, targeting older adults,Citation49,Citation50 to promote social cohesion, which may, consequently, result in greater levels of well-being for older adults.

Acknowledgments

The survey was supported by The Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (Malaysia), under Science Fund Grant No. 04-01-04-SF0479.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

References

- MomtazYAHamidTAYusoffSLoneliness as a risk factor for hypertension in later lifeJ Aging Health201224469671022422758

- CrammJMvan DijkHMNieboerAPThe importance of neighborhood social cohesion and social capital for the well being of older adults in the communityGerontologist201353114215222547088

- MomtazYAIbrahimRHamidTAYahayaNSociodemographic predictors of elderly’s psychological well-being in MalaysiaAging Ment Health201115443744521500010

- ChumblerNRLeechTThe impact of neighborhood cohesion on older individuals’ self-rated health statusKronenfeldJJSocial determinants, health disparities and linkages to health and health careBingley, UKEmerald Group Publishing20134155

- HarphamTGrantEThomasEMeasuring social capital within health surveys: key issuesHealth Policy Plan200217110611111861592

- FoneDDunstanFLloydKWilliamsGWatkinsJPalmerSDoes social cohesion modify the association between area income deprivation and mental health? A multilevel analysisInt J Epidemiol200736233834517329315

- FisherKJLiFMichaelYClevelandMNeighborhood-level influences on physical activity among older adults: a multilevel analysisJ Aging Phys Act2004121456315211020

- CollettaNJLimTGKelles-ViitanenASocial cohesion and conflict prevention in Asia: Managing diversity through developmentWashington, DCThe World Bank2001

- CagneyKABrowningCRWenMRacial disparities in self-rated health at older ages: what difference does the neighborhood make? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci2005604S181S19015980292

- ClarkCJGuoHLunosSNeighborhood cohesion is associated with reduced risk of stroke mortalityStroke20114251212121721493914

- InoueSYorifujiTTakaoSDoiHKawachiISocial cohesion and mortality: a survival analysis of older adults in JapanAm J Public Health201310312e60e6624134379

- StaffordMMcmunnADe VogliRNeighbourhood social environment and depressive symptoms in mid-life and beyondAgeing Soc2011316893910

- MairCDiez RouxAVGaleaSAre neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidenceJ Epidemiol Community Health2008621194094618775943

- KubzanskyLDSubramanianSVKawachiIFayMESoobaderMJBerkmanLFNeighborhood contextual influences on depressive symptoms in the elderlyAm J Epidemiol2005162325326015987730

- MohnenSMGroenewegenPPVolkerBFlapHNeighborhood social capital and individual healthSoc Sci Med201172566066721251743

- SchmitzMFGiuntaNParikhNSChenKKFahsMCGalloWTThe association between neighbourhood social cohesion and hypertension management strategies in older adultsAge Ageing201241338839222166684

- KendlerKSMyersJPrescottCASex differences in the relationship between social support and risk for major depression: a longitudinal study of opposite-sex twin pairsAm J Psychiatry2005162225025615677587

- BelleDGender differences in the social moderators of stressBarnettRCBienerLBaruchGKGender and stressNew YorkFree Press1987257277

- FuhrerRStansfeldSAHow gender affects patterns of social relations and their impact on health: a comparison of one or multiple sources of support from “close persons”Soc Sci Med200254581182511999495

- MujahidMSRouxDiezMorenoffJDNeighborhood characteristics and hypertensionEpidemiology200819459059818480733

- BarreraMDistinctions between social support concepts, measures, and modelsAm J Community Psychol1986144413445

- MoodyJWhiteDRStructural cohesion and embeddedness: a hierarchical concept of social groupsAm Sociol Rev2003681103127

- BromellLCagneyKACompanionship in the neighborhood context older adults’ living arrangements and perceptions of social cohesionRes Aging201436222824324860203

- MomtazYAHamidTAYahayaNThe role of religiosity on relationship between chronic health problems and psychological well-being among Malay Muslim older personsRes J Med Sci200936188193

- MomtazYAHamidTAIbrahimRYahayaNChaiSTModerating effect of religiosity on the relationship between social isolation and psychological well-beingMent Health Relig Cult2011142141156

- SampsonRJRaudenbushSWEarlsFNeighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacyScience199727753289189249252316

- BechPOlsenLRKjollerMRasmussenNKMeasuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: a comparison of the SF-36 Mental Health subscale and the WHO-Five Well-Being ScaleInt J Methods Psychiatr Res2003122859112830302

- MomtazYAIbrahimRHamidTAYahayaNMediating effects of social and personal religiosity on the psychological well being of widowed elderly peopleOMEGA (Westport)201061214516220712141

- SiedleckiKLSalthouseTAOishiSJeswaniSThe relationship between social support and subjective well-being across ageSoc Indic Res20141172561576

- SherbourneCDStewartALThe MOS social support surveySoc Sci Med19913267057142035047

- ShroutPEBolgerNMediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendationsPsychol Methods20027442244512530702

- MacKinnonDPLockwoodCMHoffmanJMWestSGSheetsVA comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effectsPsychol Methods2002718310411928892

- ByrneBMTesting for multigroup invariance using AMOS graphics: a road less traveledStruct Eq Modeling2004112272300

- BrowningCRCagneyKANeighborhood structural disadvantage, collective efficacy, and self-rated physical health in an urban settingJ Health Soc Behav200243438339912664672

- BjornstromEERalstonMLKuhlDCSocial cohesion and self-rated health: the moderating effect of neighborhood physical disorderAm J Community Psychol2013523–430231224048811

- YipWSubramanianSVMitchellADLeeDTWangJKawachiIDoes social capital enhance health and well-being? Evidence from rural ChinaSoc Sci Med2007641354917029692

- CaetanoSSilvaCVettoreMGender differences in the association of perceived social support and social network with self-rated health status among older adults: a population-based study in BrazilBMC Geriatr201313112224229389

- OkamotoKTanakaYGender differences in the relationship between social support and subjective health among elderly persons in JapanPrev Med200438331832214766114

- FuhrerRStansfeldSAChemaliJShipleyMJGender, social relations and mental health: prospective findings from an occupational cohort (Whitehall II study)Soc Sci Med1999481778710048839

- GravSHellzenORomildUStordalEAssociation between social support and depression in the general population: the HUNT study, a cross-sectional surveyJ Clin Nurs2012211–211112022017561

- MomtazYAHamidTAIbrahimRUnmet needs among disabled elderly MalaysiansSoc Sci Med201275585986322632847

- WellmanBWortleySBrothers’ keepers: Situating kinship relations in broader networks of social supportSociol Perspect1989233273306

- PodsakoffPMMacKenzieSBLeeJYPodsakoffNPCommon method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remediesJ Appl Psychol200388587990314516251

- MaxwellSEColeDABias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediationPsychol Methods2007121234417402810

- MaxwellSEColeDAMitchellMABias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation: Partial and complete mediation under an autoregressive modelMultivariate Behav Res2011465816841

- LeiPWWuQIntroduction to structural equation modeling: issues and practical considerationsEduc Meas20072633343

- LockwoodCMDeFrancescoCAElliotDLBeresfordSAAToobertDJMediation analyses: applications in nutrition research and reading the literatureJ Am Diet Assoc2010110575376220430137

- BrownBPerkinsDDBrownGPlace attachment in a revitalizing neighborhood: individual and block levels of analysisJ Env Psychol2003233259271

- KingESamiiCSnilstveitBInterventions to promote social cohesion in sub-Saharan AfricaJ Dev Effect201023336370

- EasterlyWRitzanJWoolcockMSocial cohesion, institutions, and growthEcon Polit-Oxford2006182103120