?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Anticholinergic and sedative medications are commonly used in older adults and are associated with adverse clinical outcomes. The Drug Burden Index was developed to measure the cumulative exposure to these medications in older adults and its impact on physical and cognitive function. This narrative review discusses the research and clinical applications of the Drug Burden Index, and its advantages and limitations, compared with other pharmacologically developed measures of high-risk prescribing.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Clinical scenario

An 81-year old Caucasian female presents with complaints of a dry mouth and morning sedation. The patient lives alone in a dwelling adjacent to her daughter and son-in-law, and has also noted a decreased ability to complete her daily activities due to fatigue. Her past medical history includes hypertension, urinary incontinence, insomnia, and osteoarthritic pain. Her medications include irbesartan 300 mg daily, darifenacin 15 mg daily, temazepam 7.5 mg at night, and acetaminophen/codeine 300 mg/15 mg two tablets three times daily. Her physician referred her for medication review by a pharmacist as part of the Medication Therapy Management pharmacy practice program.Citation1

Introduction

The proportion of older people in the population is increasing globally. It is estimated that by 2050, 22% of the total world’s population will be aged over 60 years.Citation2 Current evidence shows that older people are the largest per capita consumers of medications, especially the oldest old (aged over 84 years).Citation3 The rise in polypharmacy (use of five or more medications) is driven by the growth of an aging and increasingly frail population with multiple chronic diseases.Citation4

Medication management for older adults is fast becoming a challenge for health care professionals, and establishing the balance between the benefits and risks of medication use is often difficult. Many studies have highlighted the key role of regular assessment of medication regimens by primary health care professionals. According to the US Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, it is estimated that polypharmacy costs US$50 billion annually,Citation5 and hence better evidence-based management approaches are essential to overcome polypharmacy and optimize medication use in older adults.

Some of the most commonly prescribed medications in older people include those with anticholinergic (antimuscarinic)Citation6 and sedativeCitation7,Citation8 effects, and inappropriate use of these medications is associated with adverse outcomes.Citation9 For example, studies in older adults have concluded that high use of anticholinergic medications is associated with poor cognitive functionCitation10,Citation11 and functionalCitation11 impairments. Many measures have been established to assess exposure to these types of medication in older adults, and each measure has its own role, advantages, and disadvantages.

This narrative review aims to evaluate and summarize the theoretical and practical aspects of the Drug Burden Index (DBI),Citation12 a pharmacological risk assessment tool that measures the burden of anticholinergic and sedative medications in older adults. Specifically, it analyzes the effects of these medications in older adults, summarizes the development of the DBI, discusses the evidence supporting its utilization in practice, and compares the DBI with other pharmacologically developed models that measure anticholinergic or sedative exposure in older adults.

Search strategy

A search was conducted in Medline and PubMed using the following search terms: “Drug Burden Index”, “anticholinergics”, “sedatives”, “scales”, “index”, “burden”, “model”, “older people”, “aged”, and “aging”. Published articles were reviewed starting from January 2000, and citations in reviews and research articles were also searched.

Impact of anticholinergic and sedative medications on older adults

Anticholinergic and sedative medications are used widely among older adults. Overuse of these medications has been associated with adverse drug events, some of which may limit physical and cognitive function.Citation13 The muscarinic receptor blocking action of anticholinergics may cause dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, increased heart rate,Citation14 and confusion.Citation9 Benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, antidepressants, opioid analgesics,Citation15 and other drugs acting on the central nervous system can cause sedation, delirium, and impaired functional and cognitive status. Anticholinergic and sedative medications are prescribed in older adults to treat medical conditions that usually occur later in life, such as urinary incontinence, sleep and pain disorders, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and mental illness. However, evidence suggests that often the benefits do not justify the risks for some medications in older adults, for example chronic sedative medication use for insomnia.Citation16 There is also significant evidence of an association between anticholinergic medications and neuropsychiatric adverse drug events in older adults.Citation6 Evidence further suggests that clinicians may be less aware that some medications used in older adults, that are not prescribed for their anticholinergic properties, have anticholinergic effects, peripherally and centrally;Citation9 for example, amitriptyline or doxepin for major depressive disorder. This is not surprising, as more than 600 drugs have been shown to have some degree of anticholinergic activity in vitro, with 14 of the 25 medications most commonly prescribed for older adults (in Italy) having detectable anticholinergic effects centrally.Citation17 Furthermore, there is no gold standard definition for medications with anticholinergic effects for clinicians to refer to.Citation18 As a consequence of multimorbidity and older age, many medications that act on the central nervous system and have sedative properties may result in depressive symptoms, impaired muscle strength, and worsen cognition and respiratory depression. This in turn may result in falls, fractures, hospitalization, and institutionalization.Citation19 Additionally, several anticholinergic medications also have sedative properties, for example, olanzapine or quetiapine, making older people who are using medications from both classes, and who are already at risk from polypharmacy, more vulnerable to adverse drug events and their consequences.

Development of the Drug Burden Index

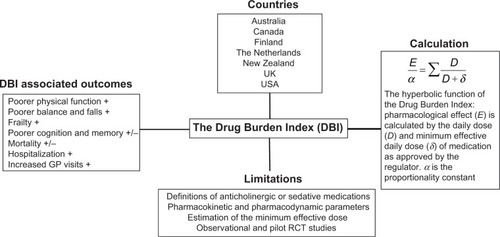

The DBI was developed and published in 2007 by Hilmer et alCitation12 and measures the effect of cumulative exposure to both anticholinergic and sedative medications on physical and cognitive function in older adults. The DBI calculation was also intended to be an evidence-based risk assessment tool to guide prescribing in older people. It was proposed that the DBI calculation could be implemented in prescribing software to inform prescribers of the likely functional implications of an older patient’s total exposure to these high-risk medications. A pharmacological equation was postulated by maintaining a classical dose–response relationship (). The researchers hypothesized that the cumulative effect of anticholinergic and sedative medications would be linear, and a simple additive model was used to establish the total anticholinergic and sedative burden. The dose of each anticholinergic and sedative medication was used to determine a score from 0 to 1 for each drug in these classes. The relationship between an individual’s DBI and their physical and cognitive performance was then evaluated in a cohort of community-dwelling older adults. It was shown that each additional unit of DBI had a negative effect on physical function similar to that of three additional physical morbidities.Citation12

Figure 1 Summary of aspects of the DBI.

Abbreviations: RCT, randomized controlled trial; GP, general practitioner.

Mathematically, the drug burden is calculated for every patient according to the formula Total Drug Burden = BAC + BS, where B indicates burden, AC indicates anticholinergic, and S indicates sedative. Assuming that the anticholinergic and sedative effects of different drugs are additive in a linear fashion,Citation20 it was postulated that BAC and BS may be proportional to a linear additive model of pharmacological effect (E). This led to the formation of the equation,

where α is a proportionality constant, D is the daily dose, and DR50 is the daily dose required to achieve 50% of maximal contributory effect at steady state. Furthermore, as the general DR50 of anticholinergic and sedative effect is not identifiable and doses need to be normalized, the DR50 was estimated as the minimum recommended daily dose (δ) as listed by the medication product information approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (). As there are some differences between countries in the δ of medications, subsequent studies using the DBI have used the minimum recommended daily dose in the study population setting. Besides being influenced by regulatory factors, the minimum daily dose accounts for additional factors that may influence drug effects such as genetics, ethnicity, diet, and environment. This flexibility allows the tool to be tailored for specific countries, for example, diazepam has a minimum registered/licensed dose of 4 mg in the USA and 5 mg in Australia.

Table 1 Example of mathematical calculation of the Drug Burden Index (using clinical scenario)

The DBI is one of the few cumulative medication exposure measures that considers the dose. Furthermore, medications that are reported to be both sedative and anticholinergic are considered as anticholinergic to prevent double entries, and therefore a separate anticholinergic DBI can be calculated from the DBI. Originally, medications with clinically significant anticholinergic or sedative effects were identified by means of Mosby’s Drug ConsultCitation21 and the Physicians’ Desk Reference.Citation22 Further observational studies have used various country-specific resources to identify these high-risk medications with similar findings, reflecting the adaptability of the equation to the investigation setting.

Validation studies of the Drug Burden Index

Increasing DBI exposure has been associated with poorer physical function,Citation23–Citation26 frailty,Citation27 and falls.Citation28,Citation29 With regard to hospitalization, a higher DBI has also been associated with increased hospital days, increased hospitalization for delirium, and readmission to hospital ().

Table 2 Evidence supporting the association of the Drug Burden Index with outcomes: cross-sectional and longitudinal studies categorized by participant setting

There have been mixed reports on the association of DBI with mortality and cognition. One study conducted in people living in residential care facilities in Australia reported a non-significant association between high DBI and mortality.Citation30 A study conducted in the Netherlands on older patients admitted to hospital with hip fractures showed a significant univariate but not multivariate association of increasing anticholinergic component of the DBI with one-year mortality.Citation18 A population-based study of older people in New Zealand found that DBI exposure increased the risk of mortality,Citation28 and a study in Finland found an association of high DBI exposure with mortality in people with and without Alzheimer’s disease.Citation31

Regarding cognition, the original validation study in the USACitation12 found that increasing DBI was associated with impaired cognition in community-dwelling older people when measured using the digit symbol substitution test; however, no associations were observed between DBI and cognition in a cohort of community-dwelling older men in Australia.Citation32 Observational studies conducted in older adults from different international settings generate relatively consistent findings, confirming a trend towards prescribing of these high-risk medications and poorer physical function outcomes in older adults.

Utility of the Drug Burden Index in practice

Currently, most studies of DBI in clinical practice have been observational. Limited studies have investigated associations between pharmaceutical service provision, prescribing outcomes, and functional outcomes in older adults (). In Australia, Home Medicine Review and Residential Medication Management Review are community-based collaborative services provided by general practitioners and pharmacists and fall under the Commonwealth-funded Medication Management Initiatives.Citation33 Two retrospective analyses have investigated DBI associations before and after Home Medicine Review and Residential Medication Management Review services, respectively. Castelino et alCitation34 concluded that the recommendations provided by a pharmacist as part of the service resulted in a significant reduction in the sum total of DBI scores for all patients. Similarly, Nishtala et alCitation35 found that DBI scores of participants were significantly lower after the pharmacist-led Residential Medication Management Review intervention. In both studies, the DBI was used as a screening or evaluation tool to measure service provision, the quality of pharmacists’ recommendations, and prescribing changes by general practitioners following uptake of recommendations. As these studies were retrospective in nature, it was not possible to assess changes in function and cognition of subjects. Additionally, these studies suggest that the DBI may be used to evaluate medication therapy management services, alongside other markers such as polypharmacy (five or more medications), hyperpolypharmacy (ten or more medications),Citation27 or use of psychotropic medications (Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act 1987)Citation36 to demonstrate prescribing appropriateness and predict functional outcomes in older adults.

Table 3 Studies of the Drug Burden Index in clinical practice

To date, only one interventional study has been conducted in the primary care setting using the DBI. This was a pilot cluster, randomized controlled trial in people aged ≥70 years living in retirement villages.Citation37 For participants in the intervention group general practitioners were provided with patient-specific information on their patient’s DBI and its health/functional implications, and were asked to consider cessation or dose reduction of anticholinergic and sedative medications contributing to DBI. For those in the control group, general practitioners were provided with their patient’s medication list only. Amongst those with DBI >0 at baseline, DBI was reduced in 32% of the intervention group and in 19% of control participants.Citation37 However, this approach only targeted general practitioners, and may reflect the poor effectiveness of the intervention design. Recent reviews state the lack of evidence for clinical effectiveness and sustainability of varying interventions to reduce polypharmacy.Citation38,Citation39 Further studies have demonstrated that multidisciplinary interventions using various intervention combinations (such as educational material, computerized support systems, medication reviews by pharmacists) are more effective than single interventions, such as that used in the pilot randomized controlled trial,Citation37 at reducing inappropriate prescribing in older people.Citation39,Citation40

Conclusively, these studies demonstrate the need for further research into multidisciplinary and multifactorial interventions using the DBI to evaluate prescribing and functional outcomes in older adults.

Theoretical aspects of the Drug Burden Index

Given its novelty and adaptability, the DBI has many theoretical applications in various settings for evaluating appropriate prescribing of anticholinergic and sedative medications in older adults. The original study by Hilmer et alCitation12 suggested that the DBI “by means of prescribing software” can inform clinicians of the implications of these high-risk medications in older people. Computerized decision support systems and computerized advice on drug dosage have been shown to improve prescribing practices, but have a mixed impact on patient outcomes.Citation41–Citation43 A recent meta-analysis concluded that electronic decision support systems that provided recommendations to both patients and clinicians may improve the success of interventions.Citation44 Currently, the DBI is being developed as a software for use by pharmacists and general practitioners during the medication review process.Citation45

Furthermore, as the DBI has been validated across a number of countries, there may be many international applications of the DBI. Faure et alCitation46 suggested that standardizing the DBI calculation with the defined daily dose, as determined by the World Health Organization, would result in a universal quality indicator in drug management, ie, the “international DBI”. While there are concerns about the validity of the defined daily dose as an estimate of DR50,Citation47 an international DBI would allow comparison of anticholinergic and sedative medication exposure and clinical outcomes in older patients globally, and could be applied to developing countries without national formularies.

Considerations when interpreting the Drug Burden Index

Like other pharmacological-based scales, the DBI has various limitations which must be considered when applying the tool in clinical settings. As discussed in the literature, it is difficult to determine exactly what constitutes an anticholinergic or sedative medication. There is no consensus on how to define an anticholinergic drug.Citation20 Several scales have been developed by consensus panels and expert opinion. This may be difficult to justify unless the method used to arrive at consensus (for example, the Delphi method) is clearly stated for the purpose investigated, and conflicts of interest are put forward, so as not to introduce bias to the outcome.Citation48 The DBI uses the drug monograph to determine whether a drug has an anticholinergic or sedative effect by considering aspects of the pharmacology and side effect profiles. However, this method is also subject to interpretation bias. For example, anticholinesterases do not form part of the anticholinergic component of the DBI, but are included in the sedative component, and hence may cause confusion when calculating the DBI for a patient.

In terms of the calculation itself, the DR50 is estimated as the minimum efficacious dose according to the approved product information. However, it does not take into account the specific indication nor interpatient pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic variations. This estimate is based on the regulatory principle that a registered dose must have some efficacy and that the minimum dose is likely to have less than maximal efficacy. The minimum recommended daily dose (δ) was used as an estimate of the dose needed to achieve 50% of the maximum effect. The accuracy of the estimate of minimum efficacious dose may differ among drugs and subjects with different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics. The DBI also assumes a linear dose-response relationship between drug classes. All medications with clinically relevant sedative or anticholinergic properties are considered equivalent, which may overestimate or underestimate the effect of the medication on the patient clinically.

Furthermore, previous studies considering the DBI have excluded the use of “as required” medications. Estimates of exposure to different dosing forms of medications (topical creams, eye drops, patches) have also not been clearly explained. This again may overestimate or underestimate the use of the anticholinergic or sedative medication of interest.

Drug response varies with basic physiological and pharmacological factors such as genetic variations, gender variations, and ethnicity. Additionally, in older adult populations, factors such as multimorbidity, polypharmacy, changes in organ function (such as liver or renal clearance), and frailty need to be considered when calculating medication burden.Citation49 None of these factors are accounted for by the DBI calculation. Validation studies conducted in various countries and settings have demonstrated a wide range of prevalence of exposure to DBI medications, from 20% to 79% (). This variability may be related to varying definitions of anticholinergic and sedative medications sourced from monographs in different countries, specific sociodemographic or health status characteristics of participants, and factors related to the health care system influencing prescription of these medications. Furthermore, modifications to the DBI calculation may limit the validity and interpretation of the tool with important clinical outcomes. A recent studyCitation50 used a modified DBI calculation to conclude that higher DBI scores were associated with poor clinical outcomes and longer lengths of hospital stay. However, this study did not comment on associations with these clinical outcomes if the calculation was kept consistent with previous studies. The modified DBI may lead to overestimation or underestimation of the association of anticholinergic and sedative medication burden with important clinical outcomes in older adults.

Finally, as previously described, the evidence for the external validity and clinical applicability of the DBI is from observational studies and one pilot interventional study. Furthermore, several studies by Gnjidic et alCitation23,Citation27,Citation32 were conducted in older male adults, and extrapolating data to females may be limited due to the differences in prescribing medications and variations in disease prevalence, functional impairment, and frailty between sexes.

Comparison of Drug Burden Index with other evidence-based pharmacological tools

Several measures of inappropriate prescribing have been developed with research on its prevalence, its association with adverse outcomes, and interventions to reduce this type of medication exposure. Various explicit and implicit inappropriate medication use scales, such as the Beers criteria,Citation51 STOPP/START (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescrip tions/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment) criteria,Citation52,Citation53 Medication Appropriateness Index,Citation54,Citation55 and Australian Indicators,Citation56,Citation57 are primarily used as general prescribing indicator tools across all medication classes rather than specifically with anticholinergic and sedative medications. Several other scales have been developed for evaluating exposure to anticholinergic or sedative medications alone. Examples of the anticholinergic scales include the Anticholinergic Drug Scale,Citation58 the Anticholinergic Burden Classification,Citation59 Clinician-rated Anticholinergic Score,Citation60 Anticholinergic Risk Scale,Citation61 Anticholinergic Activity Scale,Citation62 Anticholinergic Load Scale,Citation63 and Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale,Citation64 whilst the scales to determine the cumulative effects of taking multiple medications with sedative properties include the Sedative Load Model,Citation65,Citation66 the Sloane Model,Citation67 the Central Nervous System Drug Model,Citation68–Citation70 and the Antipsychotic Monitoring Tool.Citation71 However, when it comes to which scale or pharmacological indicator tool to apply for an older adult to make a decision related to medication management in clinical practice, selecting the right tool for the individual patient situation is challenging for health care professionals. Each anticholinergic and sedative pharmacological tool has specific advantages and disadvantages based on the original study objectives and populations. Furthermore, only a few scales have been used in randomized controlled trials to determine prescribing outcomes in older adults.Citation37,Citation72

There is considerable variation among the anticholinergic scalesCitation14 which is not surprising since the methodologies used to calculate and develop these scales vary significantly (). Additionally, a recent study concluded that there was poor agreement between the Anticholinergic Drug Scale, Anticholinergic Risk Scale, and Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale, and suggested the scales could not be applied to varying study settings unless consistently updated.Citation73 Furthermore, it has been proposed that a definitive international list of anticholinergic medications is important to build credible screening tools and to translate research with these scales to associations with clinical outcomes in older adults.Citation46 However, establishing this “definitive” list would be difficult, as there are conflicting data in the literature on what constitutes an anticholinergic drug. Compiling such a list would require standardization of the anticholinergic effects in a typical older adult who has varied pharmacological exposures and physiological functions, and is subjected to external factors such as genetics, ethnicity, diet and environment.

Table 4 Comparison of developing and calculating anticholinergic scales (by publication year) with the Drug Burden IndexTable Footnote*

It has been argued that the gold standard for assessing a drug’s anticholinergic effect remains the serum anticholinergic activity.Citation58 However, a recent study found that clinical anticholinergic effects in patients were only partially associated with serum anticholinergic activity,Citation18 adding to the complexity of defining an anticholinergic drug. Serum anticholinergic activity assays using peripheral blood may misrepresent anticholinergic effects centrally.

Similarly, in terms of sedative medications, universal definitions of what constitutes a sedative medication or a sedative load are lacking (). A review comparing four methods to quantify the effect of sedative medications on older people concluded that the usefulness of each method in clinical practice is yet to be determined.Citation15 Pharmacological tools that are developed using various methods ( and ) should be applied to population settings originally described which investigated the outcomes they were designed to predict. Tools may be successively adapted according to medications available in the country investigated and revalidated in the new setting. This will more accurately reflect the impact of these medications on older adults in the setting investigated, but propose a challenge to compare outcomes globally. Overall, an ideal pharmacological tool to investigate high-risk medication use in older adults in clinical practice should be accurate, reliable, easily accessible, easy-to-use, adaptable to the setting, based on current evidence, and provide evidence-based information that is consistently updated, to guide prescribing or drug withdrawal.

Table 5 Comparison of developing sedative scales (by publication year) with the Drug Burden IndexTable Footnote*

Future: Drug Burden Index and deprescribing

The term “deprescribing” has recently been discussed in the literature and describes the process of ceasing of unnecessary or harmful medications, especially in older adults.Citation74,Citation75 Deprescribing has been proposed as an important aspect of medication prescribing, monitoring, and use.Citation76 The DBI, together with other scales, may have a clinical role in evaluating the medication load for a patient. Written reports of the evidence describing use of these high-risk medications and negative clinical outcomes can give prescribers the incentive to deprescribe inappropriate anticholinergic and sedative medications. Many studies have proposed use of single-active pharmacological scales in conjunction with medication review services, such as Medication Therapy Management or the Medication Management Initiative.Citation77–Citation79 Although this may facilitate action by health care professionals, such an approach focuses on anticholinergics or sedatives alone (and not in combination). A potential risk of this intervention is a shift from a patient-centered care approach when evaluating the benefits and risks of medications in older adults. While exposure to anticholinergic and sedative medications is associated with functional impairment in older adults, this does not dismiss other medication classes, such as anticoagulants, antiplatelets, and hypoglycemics, as high-risk.Citation80

Conclusion

In conclusion, as the proportion of older people in the global population grows, and the prevalence of polypharmacy, multimorbidity, and adverse outcomes associated with these increases, there are various pharmacological tools to guide health care professionals to manage medications. The DBI is a novel pharmacological evidence-based tool which measures an individual’s total exposure to anticholinergic and sedative medications and is strongly associated with functional impairment. Increasing DBI has been associated with poorer physical function, falls, frailty, hospitalization, and mortality (). Future applications of the DBI include integration into practice through online software and prescribing tools, and incorporation into deprescribing studies. The DBI is one of many tools to guide prescribing in older adults, and has a specific role in measuring the functional burden of their medications. A patient-centered multidisciplinary approach to medication management, using multiple risk assessment tools combined with regular review of medication regimens, may provide the best approach to ensure the quality use of medicines for older people worldwide.

Scenario resolution

During Medication Therapy Management, the pharmacist conducted a comprehensive medication review. In the report back to the primary care physician, the pharmacist reported a DBI of 1.6 (), which translates to a negative effect on physical function on this patient greater than that of three additional physical comorbidities.Citation12 Furthermore, this patient was at a high risk of falls. The medication-related action plan included deprescribing temazepam, discussing non-pharmacological strategies for insomnia, reassessing the need for high-dose darifenacin and reducing the dose, and replacing the acetaminophen/codeine combination with acetaminophen alone, while monitoring the osteoarthritic pain. These were also outlined in the patient’s personal medication record. After one month, the dose of darifenacin was reduced and the codeine ceased. The patient’s dry mouth and fatigue had resolved and she reported improvement in her activities of daily living. While initially reluctant to withdraw temazepam, the patient was now considering this, following direct-to-patient education about the risks of benzodiazepine useCitation81 and in view of the improvements she had already experienced after reducing her anticholinergic and sedative medication load.Citation82

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- American Pharmacists AssociationNational Association of Chain Drug Stores FoundationMedication therapy management in pharmacy practice: core elements of an MTM service model (version 2.0)J Am Pharm Assoc2008483341353

- World Health OrganisationAgeing and life course: interesting facts about ageingGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organisation2012 Available from: http://www.who.int/ageing/about/facts/en/index.html#Accessed July 9, 2014

- LinjakumpuTHartikainenSKlaukkaTVeijolaJKiveläS-LIsoahoRUse of medications and polypharmacy are increasing among the elderlyJ Clin Epidemiol200255880981712384196

- WiseJPolypharmacy: a necessary evilBMJ2013347f703324286985

- BushardtRLMasseyEBSimpsonTWAriailJCSimpsonKNPolypharmacy: misleading, but manageableClin Interv Aging20083238338918686760

- NishtalaPSFoisRAMcLachlanAJBellJSKellyPJChenTFAnticholinergic activity of commonly prescribed medications and neuropsychiatric adverse events in older peopleJ Clin Pharmacol200949101176118419783711

- RothbergMBHerzigSJPekowPSAvruninJLaguTLindenauerPKAssociation between sedating medications and delirium in older inpatientsJ Am Geriatr Soc201361692393023631415

- Ineke NeutelCSkurtveitSBergCPolypharmacy of potentially addictive medication in the older persons – quantifying usagePharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf201221219920621796722

- BellJSMezraniCBlackerNAnticholinergic and sedative medicines – prescribing considerations for people with dementiaAust Fam Physician2012411–2454922276284

- FoxCRichardsonKMaidmentIDAnticholinergic medication use and cognitive impairment in the older population: the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing studyJ Am Geriatr Soc20115981477148321707557

- KoyamaASteinmanMEnsrudKHillierTAYaffeKLong-term cognitive and functional effects of potentially inappropriate medications in older womenJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci201469442342924293516

- HilmerSNMagerDESimonsickEMA Drug Burden Index to define the functional burden of medications in older peopleArch Intern Med2007167878178717452540

- FeinbergMThe problems of anticholinergic adverse effects in older patientsDrugs Aging1993343353488369593

- DuranCEAzermaiMVander SticheleRHSystematic review of anticholinergic risk scales in older adultsEur J Clin Pharmacol20136971485149623529548

- TaipaleHTHartikainenSBellJSA comparison of four methods to quantify the cumulative effect of taking multiple drugs with sedative propertiesAm J Geriatr Pharmacother20108546047121335299

- GlassJLanctotKLHerrmannNSprouleBABustoUESedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefitsBMJ20053317526116916284208

- CancelliIBeltrameMGigliGLValenteMDrugs with anticholinergic properties: cognitive and neuropsychiatric side-effects in elderly patientsNeurol Sci2009302879219229475

- MangoniAAvan MunsterBCWoodmanRJde RooijSEMeasures of anticholinergic drug exposure, serum anticholinergic activity, and all-cause postdischarge mortality in older hospitalized patients with hip fracturesAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201321878579323567395

- CraigDPassmoreAPFullertonKJFactors influencing prescription of CNS medications in different elderly populationsPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf200312538338712899112

- KerstenHWyllerTBAnticholinergic drug burden in older people’s brain – how well is it measured?Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol2014114215115924112192

- NissenDMosby’s Drug ConsultSt Louis, MO, USAMosby Inc2004

- DuplayDPhysicians’ Desk Reference58th edMontvale, NJ, USAThomson PDR2004

- GnjidicDLe CouteurDGAbernethyDRHilmerSNDrug Burden Index and Beers criteria: impact on functional outcomes in older people living in self-care retirement villagesJ Clin Pharmacol2012522258265

- GnjidicDCummingRGLe CouteurDGDrug Burden Index and physical function in older Australian menBr J Clin Pharmacol20096819710519660007

- GnjidicDBellJSHilmerSNLonnroosESulkavaRHartikainenSDrug Burden Index associated with function in community-dwelling older people in Finland: a cross-sectional studyAnn Med201244545846721495785

- WilsonNMHilmerSNMarchLMAssociations between Drug Burden Index and physical function in older people in residential aged care facilitiesAge Ageing201039450350720501606

- GnjidicDHilmerSNBlythFMHigh-risk prescribing and incidence of frailty among older community-dwelling menClin Pharmacol Ther201291352152822297385

- NishtalaPSNarayanSWWangTHilmerSNAssociations of Drug Burden Index with falls, general practitioner visits, and mortality in older peoplePharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf201423775375824723335

- WilsonNMHilmerSNMarchLMAssociations between Drug Burden Index and falls in older people in residential aged careJ Am Geriatr Soc201159587588021539525

- WilsonNMHilmerSNMarchLMAssociations between Drug Burden Index and mortality in older people in residential aged care facilitiesDrugs Aging201229215716522276959

- GnjidicDHilmerSNHartikainenSImpact of high risk drug use on hospitalization and mortality in older people with and without Alzheimer’s disease: a national population cohort studyPLoS One201491e8322424454696

- GnjidicDLe CouteurDGNaganathanVEffects of Drug Burden Index on cognitive function in older menJ Clin Psychopharmacol201232227327722367653

- Community Pharmacy Agreement. Medication Management Initiatives Available from: http://5cpa.com.au/programs/medication-management-initiatives/home-medicines-review/Accessed July 10, 2013

- CastelinoRLHilmerSNBajorekBVNishtalaPChenTFDrug Burden Index and potentially inappropriate medications in community-dwelling older people: the impact of Home Medicines ReviewDrugs Aging201027213514820104939

- NishtalaPSHilmerSNMcLachlanAJHannanPJChenTFImpact of residential medication management reviews on Drug Burden Index in aged-care homes: a retrospective analysisDrugs Aging200926867768619685933

- LantzMSGiambancoVBuchalterENA ten-year review of the effect of OBRA-87 on psychotropic prescribing practices in an academic nursing homePsychiatr Serv19964799519558875659

- GnjidicDLe CouteurDGAbernethyDRHilmerSNA pilot randomized clinical trial utilizing the Drug Burden Index to reduce exposure to anticholinergic and sedative medications in older peopleAnn Pharmacother201044111725173220876826

- GnjidicDLe CouteurDGKouladjianLHilmerSNDeprescribing trials: methods to reduce polypharmacy and the impact on prescribing and clinical outcomesClin Geriatr Med201228223725322500541

- PattersonSMHughesCKerseNCardwellCRBradleyMCInterventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older peopleCochrane Database Syst Rev20125CD00816522592727

- KaurSMitchellGVitettaLRobertsMSInterventions that can reduce inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: a systematic reviewDrugs Aging200926121013102819929029

- DurieuxPTrinquartLColombetIComputerized advice on drug dosage to improve prescribing practiceCochrane Database Syst Rev20083CD00289418646085

- GargAXAdhikariNKMcDonaldHEffects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic reviewJAMA2005293101223123815755945

- HemensBJHolbrookATonkinMComputerized clinical decision support systems for drug prescribing and management: a decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic reviewImplement Sci201168921824383

- RoshanovPSFernandesNWilczynskiJMFeatures of effective computerised clinical decision support systems: meta-regression of 162 randomised trialsBMJ2013346f65723412440

- KouladjianLGnjidicDChenTHilmerSPP009 – Development, validation and usability of software to calculate the Drug Burden Index: a pilot studyClin Ther201335Suppl 8e19

- FaureRDauphinotVKrolak-SalmonPMouchouxCA standard international version of the Drug Burden Index for cross-national comparison of the functional burden of medications in older peopleJ Am Geriatr Soc20136171227122823855856

- HilmerSNGnjidicDAbernethyDRDrug Burden Index for international assessment of the functional burden of medications in older peopleJ Am Geriatr Soc201462479179224731040

- JonesJHunterDConsensus methods for medical and health services researchBMJ199531170013763807640549

- McLachlanAJHilmerSNLe CouteurDGVariability in response to medicines in older people: phenotypic and genotypic factorsClin Pharmacol Ther200985443143319225449

- FloroffCKSlattumPWHarpeSETaylorPBrophyGMPotentially inappropriate medication use is associated with clinical outcomes in critically ill elderly patients with neurological injuryNeurocrit Care582014 [Epub ahead of print]

- American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert PanelAmerican Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc201260461663122376048

- GallagherPRyanCByrneSKennedyJO’MahonyDSTOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Consensus validationInt J Clin Pharmacol Ther2008462728318218287

- GallagherPFO’ConnorMNO’MahonyDPrevention of potentially inappropriate prescribing for elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial using STOPP/START criteriaClin Pharmacol Ther201189684585421508941

- HanlonJTSchmaderKEThe Medication Appropriateness Index at 20: where it started, where it has been, and where it may be goingDrugs Aging2013301189390024062215

- SamsaGPHanlonJTSchmaderKEA summated score for the Medication Appropriateness Index: development and assessment of clinimetric properties including content validityJ Clin Epidemiol19944788918967730892

- BasgerBJChenTFMolesRJInappropriate medication use and prescribing indicators in elderly Australians: development of a prescribing indicators toolDrugs Aging200825977779318729548

- BasgerBJChenTFMolesRJValidation of prescribing appropriateness criteria for older Australians using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness methodBMJ Open201225

- CarnahanRMLundBCPerryPJPollockBGCulpKRThe Anticholinergic Drug Scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: associations with serum anticholinergic activityJ Clin Pharmacol200646121481148617101747

- AncelinMLArteroSPortetFDupuyAMTouchonJRitchieKNon-degenerative mild cognitive impairment in elderly people and use of anticholinergic drugs: longitudinal cohort studyBMJ2006332753945545916452102

- HanLAgostiniJVAlloreHGCumulative anticholinergic exposure is associated with poor memory and executive function in older menJ Am Geriatr Soc200856122203221019093918

- RudolphJLSalowMJAngeliniMCMcGlincheyREThe anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older personsArch Intern Med2008168550851318332297

- EhrtUBroichKLarsenJPBallardCAarslandDUse of drugs with anticholinergic effect and impact on cognition in Parkinson’s disease: a cohort studyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201081216016519770163

- SittironnaritGAmesDBushAIEffects of anticholinergic drugs on cognitive function in older Australians: results from the AIBL studyDement Geriatr Cogn Disord201131317317821389718

- BoustaniMCampbellNMungerSMaidmentIFoxCImpact of anticholinergics on the aging brain: a review and practical applicationAging Health200843311320

- LinjakumpuTHartikainenSKlaukkaTKoponenHKivelaSLIsoahoRA model to classify the sedative load of drugsInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200318654254412789678

- LinjakumpuTAHartikainenSAKlaukkaTJSedative drug use in the home-dwelling elderlyAnn Pharmacother200438122017202215507503

- SloanePIveyJRothMRoedererMWilliamsCSAccounting for the sedative and analgesic effects of medication changes during patient participation in clinical research studies: measurement development and application to a sample of institutionalized geriatric patientsContemp Clin Trials200829214014817683997

- BoudreauRMHanlonJTRoumaniYFCentral nervous system medication use and incident mobility limitation in community elders: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition studyPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf2009181091692219585466

- HanlonJTBoudreauRMRoumaniYFNumber and dosage of central nervous system medications on recurrent falls in community elders: the Health, Aging and Body Composition studyJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200964449249819196642

- WrightRMRoumaniYFBoudreauREffect of central nervous system medication use on decline in cognition in community-dwelling older adults: findings from the Health, Aging And Body Composition StudyJ Am Geriatr Soc200957224325019207141

- National Prescribing Service LimitedAntipsychotic Monitoring ToolSurry Hills, Australia2014 Available from: http://www.nps.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/130326/NPS_Antipsychotic_Monitoring_Tool.pdfAccessed April 16, 2014

- KerstenHMoldenEToloIKSkovlundEEngedalKWyllerTBCognitive effects of reducing anticholinergic drug burden in a frail elderly population: a randomized controlled trialJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci201368327127822982689

- LertxundiUDomingo-EchaburuSHernandezRPeralJMedranoJExpert-based drug lists to measure anticholinergic burden: similar names, different resultsPsychogeriatrics2013131172423551407

- AlldredDPDeprescribing: a brave new word?Int J Pharm Pract20142212324404932

- FrankCDeprescribing: a new word to guide medication reviewCMAJ2014186640740824638028

- WoodwardMCDeprescribing: achieving better health outcomes for older people through reducing medicationsJ Pharm Pract Res200333323328

- HeZKBallPACan medication management review reduce anticholinergic burden (ACB) in the elderly? Encouraging results from a theoretical modelInt Psychogeriatr20132591425143123782833

- WestTPruchnickiMCPorterKEmptageREvaluation of anticholinergic burden of medications in older adultsJ Am Pharm Assoc2013535496504

- GouldRLCoulsonMCPatelNHighton-WilliamsonEHowardRJInterventions for reducing benzodiazepine use in older people: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsBr J Psychiatry201420429810724493654

- BudnitzDSLovegroveMCShehabNRichardsCLEmergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older AmericansN Engl J Med2011365212002201222111719

- TannenbaumCMartinPTamblynRBenedettiAAhmedSReduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trialJAMA Intern Med2014174689089824733354

- JoesterJVoglerCMChangKHilmerSNHypnosedative use and predictors of successful withdrawal in new patients attending a falls clinic: a retrospective, cohort studyDrugs Aging2010271191592420964465

- LonnroosEGnjidicDHilmerSNDrug Burden Index and hospitalization among community-dwelling older peopleDrugs Aging201229539540422530705

- LowryEWoodmanRJSoizaRLHilmerSNMangoniAADrug Burden Index, physical function, and adverse outcomes in older hospitalized patientsJ Clin Pharmacol201252101584159122167569

- SwannickGPrescribing information. eMIMS (CD-ROM)St Leonards, AustraliaMonthly Index of Medical Specialties

- BosboomPRAlfonsoHAlmeidaOPBeerCUse of potentially harmful medications and health-related quality of life among people with dementia living in residential aged care facilitiesDement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra20122136137123277778

- HilmerSNMagerDESimonsickEMDrug Burden Index score and functional decline in older peopleAm J Med2009122121142114919958893

- KashyapMBellevilleSMulsantBHMethodological challenges in determining longitudinal associations between anticholinergic drug use and incident cognitive declineJ Am Geriatr Soc201462233634124417438

- NarayanSWHilmerSNHorsburghSNishtalaPSAnticholinergic component of the Drug Burden Index and the anticholinergic drug scale as measures of anticholinergic exposure in older people in New Zealand: a population-level studyDrugs Aging2013301192793423975730

- NishtalaPSNarayanSWangTHilmerSNAssociations of Drug Burden Index with falls, general practitioner visits, and mortality in older peoplePharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf201423775375824723335

- CummingRGHandelsmanDSeibelMJCohort profile: the Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project (CHAMP)Int J Epidemiol200938237437818480109

- BestOGnjidicDHilmerSNNaganathanVMcLachlanAJInvestigating polypharmacy and Drug Burden Index in hospitalised older peopleIntern Med J201343891291823734965

- DispennetteRElliottDNguyenLRichmondRDrug Burden Index score and anticholinergic risk scale as predictors of readmission to the hospitalConsult Pharm201429315816824589765

- HanLMcCuskerJColeMAbrahamowiczMPrimeauFElieMUse of medications with anticholinergic effect predicts clinical severity of delirium symptoms in older medical inpatientsArch Intern Med200116181099110511322844

- ChewMLMulsantBHPollockBGAnticholinergic activity of 107 medications commonly used by older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc20085671333134118510583