Abstract

Elderly patients (age ≥65 years) with hypertension are at high risk for vascular complications, especially when diabetes is present. Antihypertensive drugs that inhibit the renin-angiotensin system have been shown to be effective for controlling blood pressure in adult and elderly patients. Importantly, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors were shown to have benefits beyond their classic cardioprotective and vasculoprotective effects, including reducing the risk of new-onset diabetes and associated cardiovascular effects. The discovery that the renin-angiotensin system inhibitor and angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor blocker (ARB), telmisartan, can selectively activate the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ, an established antidiabetic drug target) provides the unique opportunity to prevent and treat cardiovascular complications in high-risk elderly patients with hypertension and new-onset diabetes. Two large clinical trials, ONTARGET (Ongoing Telmisartan Alone in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial) and TRANSCEND (Telmisartan Randomized AssessmeNt Study in ACE-I iNtolerant subjects with cardiovascular disease) have assessed the cardioprotective and antidiabetic effects of telmisartan. The collective data suggest that telmisartan is a promising drug for controlling hypertension and reducing vascular risk in high-risk elderly patients with new-onset diabetes.

Introduction

The worldwide increase in the elderly population (age ≥65 years) is associated with concurrent increases in prevalence of systemic hypertension and morbidity and mortality from vascular complications of hypertensive disease.Citation1 The elderly population with hypertension and new-onset diabetes is at especially high risk for vascular complications. Citation1 Antihypertensive drugs that inhibit the renin-angiotensin system have been shown to control blood pressure effectively in adult and elderly patients.Citation2–Citation8 Importantly, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors have been shown to have benefits beyond their classic cardioprotective and vasculoprotective effects, including reducing the risk of new-onset diabetes.Citation2,Citation3 Evidence from randomized clinical trials suggests that this may be a class effect of the renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. Recently, the ability of the renin-angiotensin system inhibitor and angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor blocker (ARB), telmisartan, to activate the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) selectively, an established antidiabetic drug target, provides the unique opportunity to prevent and treat cardiovascular complications in high-risk elderly patients with hypertension and new-onset diabetes.Citation9–Citation13 Telmisartan has been shown to have beneficial effects on hypertension, as well as lipid and glucose metabolism,Citation9–Citation13 without the side effects of fluid retention, weight gain, and heart failure associated with thiazolidinedione ligands of PPARγ.Citation14 Combined renin-angiotensin system inhibition and selective PPARγ modulation with telmisartan could therefore provide additional protection in elderly hypertensive patients with new-onset diabetes compared with renin-angiotensin system inhibition alone.

Recently, two large randomized clinical trials, ONTARGET (Ongoing Telmisartan Alone in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial)Citation15,Citation16 and TRANSCEND (Telmisartan Randomized AssessmeNt Study in ACE-I iNtolerant subjects with cardiovascular disease)Citation17,Citation18 have assessed the cardioprotective and antidiabetic effects of telmisartan and the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor ramipril in high-risk, mostly elderly patients.Citation15–Citation18 A few small studies evaluated the efficacy of telmisartan in elderly patients with primary hypertension alone,Citation19 or associated with cerebral infarction,Citation20 type 2 diabetes,Citation21 and metabolic syndrome.Citation22 This article reviews the clinical effectiveness of telmisartan alone or in combination therapy for controlling blood pressure and vascular risk in the elderly.

Who are the elderly people?

Because aging is a continuous biologic process, there is no biomarker that separates elderly from nonelderly patients. Evidence indicates that aging leads to multiple changes ( and ) that impact cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology.Citation23 The chronologic age of 65 years became the definition of elderly by default.Citation24 Data from population studies and randomized clinical trials since the 1950s suggest that this arbitrary cutoff of 65 has clinical relevance.Citation1 Thus, the prevalence of hypertension increases progressively with age, but the vascular complications associated with hypertension increase sharply after age 65 years, including stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and renal failure.Citation1 The same is true for comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and obesity, which appear to aggravate the vascular complications.Citation1 Importantly, the negative impact of vascular complications increases with aging.Citation1 Thus, the risk of dying of myocardial infarction increases progressively across three segments, ie, the younger elderly aged 65–74 years, the older elderly aged 75–84 years, and the very elderly aged >85 years.Citation25

Table 1 Biologic changes in cardiovascular aging

Table 2 Physiologic changes and pathophysiologic hallmarks of cardiovascular aging

The elderly and cardiovascular risk

Ten points relating to the interaction between aging and cardiovascular risk factors deserve mention. First, evidence indicates that risk factors influence cardiovascular disease progression and aging is an independent predictor of mortality and morbidity.Citation1 Second, interactions between risk factors (ie, genetic factors, stress, diet, cigarette smoking, sedentary lifestyle, dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome) and the cardiovascular system lead to vascular disease (including hypertension) and its complications, including coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, carotid artery disease, stroke, left ventricular dysfunction, heart failure, peripheral artery disease, and renal failure.Citation1 Third, cardiovascular risk factors (including hypertension) contribute to vascular disease progression and end organ pathologies.Citation1 Fourth, besides hypertension, comorbidities that are prevalent in the elderly (including coronary artery disease, obesity, and type 2 diabetes) increase risk and accelerate progression toward stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, renal failure, severe disability, and death.Citation1 Fifth, aging increases risk, and cardiovascular disease is more severe and causes more deaths in elderly men and women. Sixth, the Framingham study found six main risk factors for stroke (age, systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive therapy, type 2 diabetes, cigarette smoking, and prior cardiovascular disease).Citation26,Citation27 Seventh, despite unclear associations between lipids and stroke,Citation27 studies with lipid-modifying drugs indicate that dyslipidemia is an important risk factor for stroke.Citation28 Eighth, the INTERHEART study, which ranked potentially modifiable risk factors for myocardial infarction in five age groups (<45, 46–55, 56–65, 66–70, >70 years), found that nine factors account for most of the risk of myocardial infarction, including abnormal lipids, hypertension, diabetes, and abdominal obesity.Citation29 Ninth, patients with evidence of vascular disease such as myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic stroke, and peripheral vascular disease represent a high-risk group for major cardiovascular events and the risk is greater in the elderly.Citation30,Citation31 Tenth, the role of hypertension in cardiovascular disease and the ability of antihypertensive drugs to reduce risk are well established.Citation32 In older persons with isolated systolic hypertension, a history of diabetes is an important risk factor for lacunar stroke, whereas carotid bruit and age are important risk factors for atherosclerotic and embolic stroke.Citation26

Demographics of hypertension in the elderly

In the US, hypertension def ined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, affects at least 74.5 million of the adult population.Citation1 Prevalence increases with age, with half to two-thirds of hypertensives being elderly and 75% aged >80 years. There is a gender difference, with age-adjusted prevalence between 1999 and 2002 being 78% for elderly women and 64% for elderly men. The profile of hypertension is altered with aging and there is again a gender difference; systolic blood pressure increases, whereas diastolic blood pressure stays relatively constant between age 50–80 years, with the average diastolic blood pressure higher in men than women. Isolated systolic hypertension without a rise in diastolic blood pressure occurs in 8% of the population aged 60 years and >25% in those aged >80 years.

Complications of hypertension increase with age.Citation1 The prevalence of silent stroke also increases with aging, being 22% in those aged 65–69 years, and 43% in those aged ≥85 years. Prevalence of myocardial infarction and heart failure is highest in the elderly.Citation1 Chronic conditions are also more common in the elderly, most prominent among these being heart disease and diabetes.Citation1 Diabetes also increases with aging, with the largest increases projected for the oldest groups.Citation1 More than 80% of all deaths from cardiovascular disease occur in the elderly, with approximately 60% in those aged >75 years.Citation1 For 2010, the estimated total costs (indirect plus direct) in billions are $76.6 for hypertensive disease, $73.7 for stroke, and $39.2 for heart failure, respectively.Citation1

Epidemiology of hypertension in the elderly

The pharmacologic treatment of hypertension has improved since the 1990s. However, hypertension in the elderly does not occur in isolation. Typically, other cardiovascular diseases, comorbidities, and polypharmacy are common, making therapy more challenging. The profile of hypertension, as well as commonly associated cardiovascular diseases, such as coronary heart disease and heart failure, differ from that in nonelderly patients. Systolic hypertension is common and becomes a stronger predictor of cardiovascular events, especially in older women. Heart failure is also more prevalent and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction more common, especially in older women. Coronary artery disease is more common and more likely to involve multiple vessels and the main left artery. Myocardial infarction is more prevalent and is equally distributed in elderly men and women until the age of 80 years, after which it is more frequent in women. The risk of heart failure, severity of hypertension, and hypertension with antecedent myocardial infarction increase with aging.Citation1 Myocardial infarction usually results in dilative ventricular remodeling and systolic heart failure, also called heart failure with low ejection fraction.Citation30 In contrast, hypertensive disease usually results in concentric remodeling and diastolic heart failure, also called heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.Citation30 Nearly 50% of elderly patients have heart failure with low ejection fraction whereas approximately 50% of all heart failure patients have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and its prevalence is higher in the elderly.Citation30 In a recent study of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, all patients were very elderly, with a mean age of 87 years.Citation33 Whereas pharmacologic therapies for heart failure with low ejection fraction are available, therapies for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction are lacking.Citation30 Because elevated blood pressure is the main cause, tight blood pressure control is important for prevention.

Diabetes is not only more prevalent in the elderly, but increases cardiovascular risk, and more so in the presence of hypertension and/or coronary heart disease.Citation1–Citation3 Epidemiologic studies showed that the presence of diabetes results in increased cardiovascular mortality by nearly three-fold in men and five-fold in women,Citation35 increased prevalence of coronary heart disease,Citation36 increased risk of cardiovascular disease,Citation37 and increased risk of renal disease and other macrovascular and microvascular complications.Citation1,Citation38

Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors for hypertension and cardiovascular risk in the elderly

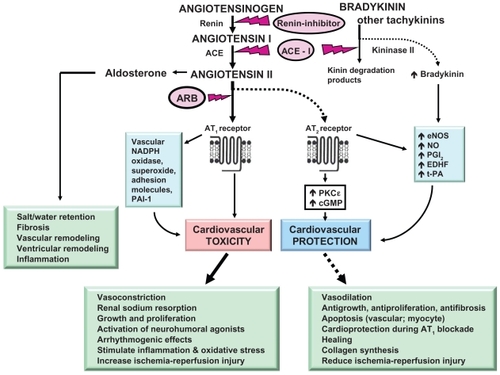

It is well recognized that the renin-angiotensin system plays a central role in regulation of blood pressure, fluid and electrolyte balance, and the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease (see ).Citation4–Citation8 Angiotensin II, the primary effector peptide of the renin-angiotensin system, not only increases blood pressure but also promotes vascular inflammation, leading to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis, stimulates vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy, and vascular remodeling, and stimulates myocardial fibrosis and hypertrophy, leading to cardiac remodeling.Citation4–Citation8 It also increases aldosterone, which stimulates fibrosis and cardiovascular remodeling (see ). Most of the effects of angiotensin II are mediated via AT1 receptors, providing a rationale for ACE inhibition and AT1 receptor blockade (see ). Importantly, aging is associated with increased angiotensin II and other renin-angiotensin system components which, in turn, may contribute to increased cardiovascular remodeling and cardiovascular risk in the elderly.Citation23

Figure 1 Pathways of cardiovascular protection induced by ACE inhibition and ARBs.

ACE inhibitors for cardiovascular risk

Cumulative evidence suggests that renin-angiotensin system activation plays a critical role in increasing cardiovascular events, and renin-angiotensin system inhibition with ACE inhibitors reduces cardiovascular risk.Citation39 ACE inhibitors effectively control blood pressure in patients with hypertension, and have additional beneficial effects on cardiovascular risk factors, including coronary heart disease, stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Randomized clinical trials have established that ACE inhibitors reduce rates of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in patients with heart failure,Citation40 left ventricular dysfunction,Citation41 vascular disease,Citation42–Citation44 and highrisk diabetes.Citation3

Four trials specifically addressed whether ACE inhibitors reduce cardiovascular events in low- to high-risk patients. First, the HOPE (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation) studyCitation2 showed improvement in prognosis using the ACE inhibitor, ramipril, with a decreased rate of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in a broad range of high-risk patients (including diabetes) for cardiovascular events and without low ejection fraction or heart failure. HOPE decreased new-onset diabetes and complications of diabetes. Second, EUROPA (European trial On reduction of cardiac events with Perindopril in stable coronary Artery disease),Citation42 which included patients with coronary artery disease at lower risk than in HOPE and without left ventricular dysfunction, showed improvement in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, and resuscitation. Third, QUIET (QUinapril Ischemic Event Trial),Citation43 which included low-risk patients, found no significant benefit. Fourth, the PEACE (Prevention of Events with Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme inhibition) trial,Citation44 which included low-risk patients and used the ACE inhibitor, trandolapril, found no significant benefit. However, the dose of the ACE inhibitors in QUIET and PEACE may have been suboptimal. Moreover, a metaanalysis of these trials, with pooled data for 31,600 patients, showed that ACE inhibitors are effective in preventing cardiovascular events, with a 26% reduction in the risk of heart failure or stroke, and a 13%–18% reduction in total and cardiovascular mortality and myocardial infarction compared with placebo.Citation45

Several studies suggested that ACE inhibitors not only reduce stroke by controlling blood pressure but may also prevent renal complications of diabetes.Citation46 The HOPE/TOO (The ongoing Outcomes) study found decreased development of diabetes in the follow-up phase, suggesting an added benefit of long-term ramipril.Citation47 In the MICRO (MIcroalbuminuria Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes) HOPE substudy,Citation3 ramipril was beneficial for cardiovascular events and overt nephropathy in patients with diabetes. In the ADVANCE (Action in Diabetes and Vascular disease: preterAx and diamicroN-MR Controlled Evaluation) trial, the ACE inhibitor, perindopril, together with the diuretic, indapamide, reduced the risks of major vascular events and death in type 2 diabetes.Citation48

AT1 receptor blockers for cardiovascular risk

Because ACE inhibitors do not block angiotensin II generated in cardiovascular and other tissues via non-ACE pathways, the ability of ARBs to block angiotensin II at the AT1 receptor selectively, resulting in more complete inhibition, was considered advantageous (see Figure).Citation49 Unlike ARBs, ACE inhibitors increase bradykinin by suppressing its degradation, thereby enhancing vasodilation, but also increasing cough and angioneurotic edema that are troublesome in approximately 20% of patients, especially in women and Asians.Citation2,Citation3,Citation49 ARBs may result in unopposed angiotensin II type 2 (AT2) receptor activation and enhance vasodilation via downstream AT2-mediated signaling.Citation49 Apart from blocking deleterious effects of angiotensin II and controlling blood pressure, ARBs might have protective effects similar to those of ACE inhibitors. Data from randomized clinical trials showed that ARBs effectively control blood pressure in hypertension and are well tolerated.Citation50 However, despite well known arguments for using ARBs, as reviewed previously,Citation49 whether ARBs are as effective as ACE inhibitors in reducing events such as stroke and myocardial infarction has been questioned.Citation51 Moreover, ARBs can also release kinins and increase bradykinin levels in hypertensive patients,Citation50,Citation52 and thereby mediate cardiovascular protection. Citation49 Such an ARB-induced increase in bradykinin can augment therapeutic actions, but can also lead to cough and angioedema.Citation50,Citation52 In the counterregulatory arm of the renin-angiotensin system, both ACE inhibitors and ARBs can increase angiotensin-(1–7).Citation49

A complicating factor with the use of ACE inhibitors in heart failure patients is that angiotensin II levels increase and symptoms worsen.Citation53 However, studies in hypertension have shown that ARBs, such as losartan and valsartan, are as effective as ACE inhibitors in lowering blood pressure.Citation54,Citation55 In hypertensive patients with ACE inhibitor-induced cough, this complication is less frequent with ARBs.Citation56 In patients with heart failure and low ejection fraction, an ARB was shown to reduce the rate of death or hospitalization relative to placebo in those patients who could not tolerate an ACE inhibitor,Citation57 or were already receiving one.Citation58,Citation59 In the LIFE (Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension) study, compared with beta-blockers, ARBs reduced vascular events in high-risk patients with hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy.Citation60 Taken together, these studies suggest that an ARB is an effective and well tolerated alternative to an ACE inhibitor for cardiovascular protection.

Because ACE inhibitors preceded ARBs for treating hypertension and heart failure, it has become necessary in clinical trials to demonstrate noninferiority or superiority of an ARB over an ACE inhibitor as comparator. In patients with myocardial infarction, two studies comparing an ARB with an ACE inhibitor produced different results. OPTIMAAL (OPtimal Trial In Myocardial infarction with Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan)Citation61 and VALIANT (VAL-sartan In Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial)Citation62 compared the ARBs, losartan and valsartan, respectively, with the ACE inhibitor, captopril, in patients with signs of heart failure within 10 days of myocardial infarction. In OPTIMAAL, the ARB was not superior and the noninferiority criteria were not met; in fact, there was an increase in cardiovascular mortality after a 2.7-year mean follow-up.Citation61 In VALIANT, the ARB was nonsuperior and noninferior for mortality and the composite endpoint of fatal and nonfatal events. The study established that valsartan was as effective as an ACE inhibitor in reducing mortality in high-risk survivors of myocardial infarction.Citation62 A meta-analysis of 54,254 patients from 11 trials showed a potential 18% increase in myocardial infarction with ARBs compared with placebo and a possible increase compared with other active therapy.Citation63 In a separate meta-analysis of 55,050 patients from 11 trials that compared ARBs with either placebo or an active comparator, ARBs were found to reduce event rates for stroke, not to reduce event rates for global death, and to increase rates of myocardial infarction by 8%.Citation51 The cloud of doubt cast by these reports has been partly dispelled by studies with the ARB telmisartan.Citation15–Citation18

Telmisartan for hypertension and cardiovascular risk

The AT1 antagonist telmisartan is an orally active, selective, biphenyl, nontetrazole, 6-substituted benzimidazole amino-peptide that has no apparent AT1 agonist activity and does not interact with other receptors involved in cardiovascular regulation.Citation9,Citation64 Studies in various experimental models have shown that telmisartan is a more potent antihypertensive agent than losartan,Citation9 and reduces glomerulosclerosis and cardiac hypertrophy.Citation9 Telmisartan has a long half-life and sustained blood pressure-lowering activity. Studies in patients showed that a telmisartan 80 mg once daily dose was very effective in lowering diastolic blood pressure,Citation65,Citation66 with no difference in pharmacokinetics found between healthy elderly and younger subjects.Citation19

Potential problems with treatment of hypertension in the elderly

Treatment of hypertension in elderly patients is more challenging than in the nonelderly because of aging-related biologic () and pathophysiologic () changes and associated comorbidities and polypharmacy. Common problems are listed in . Comorbidities, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes, not only aggravate the total cardiovascular disease burden but complicate management. Polypharmacy can lead to drug interactions.Citation67,Citation68 Typically, elderly patients have multiple drugs prescribed. Patients aged ≥65 years usually use 2–6 prescription and 1–4 nonprescription drugs on a regular basis.Citation68 Addition of other drugs substantially increases the possibility of adverse effects. The potential for an adverse effect of any drug is estimated to increase by 6% when taken with one drug, by 50% when taken with five different drugs, and by 100% when taken with eight or more medications.Citation68 Age-related changes in the gastrointestinal tract, body content of fat and water, and liver and renal function, alter drug pharmacokinetics, including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion in the elderly. In addition, elderly patients may have blunted responses to diuretics, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and positive inotropes. They may show heightened sensitivity to renal dysfunction, impairment of sodium and water excretion, postural hypotension, aggravation of hypotension to treatments (ie, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, ARBs, nitrates, hydralazine, and diuretics) besides cognitive impairment and general frailty. Because of the physiologic changes that occur with aging, several precautionary measures are necessary with the pharmacotherapy of hypertension, myocardial infarction, and heart failure in the elderly.Citation30,Citation67 Also because of the age-related changes () and impact of comorbidities, therapy needs to be individualized.

Table 3 Problems with pharmacologic therapy in the elderly

Telmisartan for hypertension in the elderly

Given its pharmacodynamic profile, telmisartan appeared well suited for treating hypertension in the elderly,Citation19,Citation69 but this needed testing. In a 26-week, multicenter study of 278 elderly patients (aged ≥65 years, mean age 71 years) with primary hypertension,Citation19 Karlberg et al used a careful dose titration scheme, starting with 20 mg and escalating to 40 mg and 80 mg of telmisartan based on the blood pressure response, and addition of hydrochlorothiazide if the 80 mg dose was not sufficient. Importantly, the dose of telmisartan was increased from 20 mg to 40–80 mg and enalapril from 5 mg to 10–20 mg at four-week intervals until the trough supine blood pressure was <90 mmHg. Only after 12 weeks, hydrochlorothiazide 12.5–25 mg once daily was added to the treatment regimen of patients who were not controlled on monotherapy.Citation19 The study showed that both regimens provided effective lowering of blood pressure over the 24-hour dosing interval based on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.

Although both regimens were well tolerated, the enalapril regimen was associated with more than double the incidence of treatment-related cough compared with the telmisartan regimen (16% versus 6.5%, respectively).Citation19 The overall findings of that small study suggested that telmisartan is well tolerated and at least as effective as enalapril for treating elderly patients with mild to moderate hypertension.Citation19 However, that study did not address cardiovascular risk.

Telmisartan and partial PPARγ agonism

In addition to renin-angiotensin system inhibition, telmisartan acts as a selective partial agonist of PPARγ, an intracellular nuclear hormone receptor that is involved in the regulation of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Discovery of this unique property of telmisartan has attracted attention because of its therapeutic potential in elderly patients with obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. Several studies have shown that PPARγ plays an important role as a regulator of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism,Citation70,Citation71 and ligands for PPARγ improve insulin sensitivity,Citation72 reduce triglyceride levels,Citation72 decrease risk of atherosclerosis,Citation73 reduce vascular and cardiac effects of hypertension,Citation74 and promote peripheral vasodilation.Citation75–Citation77

Although thiazolidinedione ligands for PPARγ were approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, these agents alone do not control blood pressure in hypertension and can provoke weight gain, edema, and heart failure in diabetics.Citation78 Despite reported beneficial effects of the thiazolidinediones, ie, pioglitazone and rosiglitazone, in animal models of ischemia-reperfusion injury and postinfarction ventricular remodeling,Citation79–Citation81 the finding that rosiglitazone increases mortality post myocardial infarction in ratsCitation82 led to grave concerns about the use of thiazolidinediones in diabetics. A teleoanalysis of clinical trials showed an increased risk of heart failure with both thiazolidinediones in patients with type 2 diabetes.Citation14 More recently, patients treated with rosiglitazone showed an increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and death in high-risk elderly diabetics compared with pioglitazone.Citation83 These side effects may not be unique to the thiazolidinedione moiety because they can also occur with nonthiazolidinedione ligands.Citation9 Thiazolidinedione-induced fluid retention and heart failure appears to be related not to left ventricular dysfunction,Citation9 but rather to increased sodium reabsorption mediated by the renal PPARγ pathway in collecting tubules.Citation84 Moreover, both thiazolidinediones are under review by the US Food and Drug Administration, and restrictions have been applied with the use of rosiglitazone. The 2010 consensus is that thiazolidinediones should be avoided in older patients with type 2 diabetes and class III/IV heart failure and should not be used for reducing cardiovascular events.

Elegant molecular modeling studies by Benson et alCitation9 established two important points. First, telmisartan is only a partial PPARγ agonist and might influence PPARγ activity by interacting with regions of the ligand-binding domain that are not typically engaged by full PPARγ agonists. Second, other ARBs lack the potential of telmisartan for receptor interaction and have little or no PPARγ activity. Given that renin-angiotensin system blockade with telmisartan can inhibit renal sodium reabsorption and attenuate fluid retention and edema, the potential heart failure complication seen with thiazolidinediones should not be a source of concern with the use of telmisartan in diabetics.Citation9

Several other clinical and experimental studies support the beneficial effect of telmisartan via PPARγ activity. First, a small comparative study of telmisartan 40–80 mg and enalapril 10–20 mg in 250 patients with hypertension and early type 2 diabetic nephropathy (age >40 years) showed that, over the five-year study period, telmisartan is noninferior to enalapril in conferring renoprotection.Citation88 Second, another small comparative study of telmisartan 80 mg and losartan 50 mg for three months in 40 patients, mean age 55–56 years, with hypertension and metabolic syndrome, showed that telmisartan provides superior control of blood pressure and displays insulin-sensitizing activity consistent with its partial PPARγ activity.Citation10 Third, telmisartan (but not eprosartan) was shown to increase nitric oxide synthesis sufficient to delay aging of human umbilical vein endothelial cells via activation of PPARγ signaling.Citation11 Fourth, telmisartan was shown to attenuate fatty acid-induced oxidative stress in mouse pancreatic β-cells, suggesting that it may preserve insulin secretion capacity in diabetics.Citation12 Fifth, a recent small study of 39 patients with essential hypertension (mean age 61 ± 6 years) showed that telmisartan 80 mg daily effectively improved vascular endothelial function and arterial stiffness after eight weeks, consistent with increased PPARγ activity.Citation13

The collective evidence suggests that, among the anti-hypertensive drugs that inhibit the renin-angiotensin system, telmisartan is safe and effective for elderly patients.Citation19 Whether its partial PPARγ agonism might be an added advantage for high-risk elderly patients needs further evaluation in larger clinical trials. Pending the results, caution might be prudent.

Do other renin-angiotensin system inhibitors have PPARγ activity?

Among other ARBs, only irbesartan was found to have significant PPARγ agonist activity, but that was modest compared with telmisartan.Citation9 A subsequent prospective observational study in 3259 patients with hypertension and metabolic syndrome or diabetes showed improvement in metabolic parameters with irbesartan 150 mg or 300 mg daily with or without hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg daily after six months.Citation85 Importantly, these changes were more pronounced in male and obese patients.Citation85 However, the mean age of the patients in that study was only 61.5 ± 10.5 years.Citation85 The renal benefits of ARBs in patients with type 2 diabetes as previously reported with losartan (albeit in patients aged 60 ± 7 years),Citation86 were most likely due to blockade of the effects of angiotensin II through the AT1 receptor,Citation86 and possibly by enhancing effects through the AT2 receptor.Citation87 The extensively reported beneficial effects of ACE inhibitors in type 2 diabetesCitation47,Citation48 are most likely due to the combined effects of increased bradykinin and decreased angiotensin II via AT1 and AT2 receptors rather than PPARγ.Citation9

ONTARGET study

The ONTARGET investigators compared telmisartan (80 mg daily, n = 8542) with the ACE inhibitor, enalapril 10 mg daily (n = 8576) as the comparator or combined with ramipril as background therapy (n = 8502) in patients with vascular disease or high-risk diabetes over a median of 56 months.Citation15 Patients aged ≥55 years were enrolled. Mean ages were 66.4 ± 7.2, 66.4 ± 7.1 and 66.5 ± 7.3 years, respectively. Mean baseline blood pressures averaged 142 ± 17/82 ± 10 mmHg in the three groups. Telmisartan was noninferior to or as effective as ramipril for prevention of the composite primary outcome (cardiovascular deaths, myocardial infarction, or heart failure hospitalization) as well as individual components of the outcome. However, blood pressure reduction was greater with telmisartan and combination therapy compared with enalapril monotherapy. Also, compared with enalapril monotherapy, telmisartan monotherapy was associated with less cough (1.1% versus 4.2%) and angioedema (0.1% versus 0.3%) and more hypotensive symptoms (2.6% versus 1.7%) and similar rates of syncope (0.2%). Compared with either monotherapy, combination therapy was associated with more adverse events (hypotensive symptoms, 4.8% versus 1.7%; syncope, 0.3% versus 0.2%; renal impairment, 13.5% versus 10.2%; hyperkalemia [>5.5 mmol/L]: combination therapy [480 patients] versus telmisartan [287 patients] versus ramipril [283 patients], P < 0.001) and without increased benefits.

Five points in ONTARGET deserve emphasis. First, although the population was similar to that in HOPE,Citation2 adherence to the ACE inhibitor, ramipril, was higher than in HOPE.Citation15 Second, the discontinuation rate was lower and compliance higher with telmisartan than with ramipril.Citation15 In previous randomized clinical trials, 20% of patients were unable to tolerate ACE inhibitors.Citation2,Citation3,Citation45 Third, although the population was quite different from that in VALIANT which selected those with left ventricular dysfunction and postinfarction heart failure, VALIANT also showed non-inferiority to an ACE inhibitor (ie, captopril).Citation62 Fourth, as in VALIANT,Citation62 a greater decrease in blood pressure with combination therapy was not associated with greater benefits, likely because of the offsetting effect of increased risk of hypotension, syncope, renal dysfunction, and hyperkalemia. In addition, the potential benefits of dual renin-angiotensin system inhibition may have been blunted by combination with beta-blockers, which were used in approximately 55% of patients. A similar interaction was noted in VALHeFT (the VALsartan HEart Failure Trial).Citation58 Fifth, in contrast with CHARM (Candesartan in Heart Failure – Assessment of Mortality and Morbidity),Citation59 which enrolled heart failure patients and added the ARB candesartan to an ACE inhibitor in variable doses (<50% on full doses), and VALHeFT,Citation58 which enrolled heart failure patients and compared valsartan with a placebo group of which 90% received background ACE inhibitors in submaximal doses, combination therapy was superior to placebo.

Taken together, the ONTARGET data suggest that there is no added advantage of combination therapy at full doses in older adult and younger elderly patients. Careful titration should be the rule when combining ARBs with ACE inhibitors, both of which are powerful vasodilators, to avoid hypotension, especially in elderly and very old patients. The dose regimen used by Karlberg et al was cautious, wise, and effective.Citation19 The harmful paradoxical J-curve or U-curve effect of decreased blood pressure and hypoperfusion with vasodilator therapy was demonstrated for acute myocardial infarction, both in experimental and clinical settings.Citation89–Citation93 This is likely true for hypertension,Citation94 especially in elderly patients with physiologic increases in cardiac and vascular stiffness (), although definitive confirmation in appropriate randomized clinical trials of more elderly patient populations is needed.Citation6

TRANSCEND study

By design, TRANSCENDCitation17 compared telmisartan 80 mg once daily (n = 2954) with placebo (n = 2972) in patients intolerant to ACE inhibitors and with cardiovascular disease or diabetes with end-organ damage over a median duration of 56 months. The patients were identified after a three-week run-in period. Mean age was 66.9 years, and baseline blood pressure averaged 141/82 mmHg for both groups. Their study population included patients selected from ONTARGET because of ACE inhibitor intolerance. Telmisartan was well tolerated, but did not affect the ONTARGET primary outcome (composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure). However, telmisartan modestly reduced the secondary outcome (composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke) compared with placebo (13.0% versus 14.8%; unadjusted P = 0.048 and adjusted P = 0.068). Discontinuation was less with telmisartan than placebo (21.6% versus 23.8%; P = 0.055) and this was mostly for hypotension (0.098% versus 0.54%; P = 0.049); rates of syncope (1% versus 0%), cough (0.51% versus 0.61%), angioedema (0.07% versus 0.10%), and renal dysfunction (0.81% versus 0.44%) were low and not different between the groups. Telmisartan had no effect on rates of hospitalization for heart failure, at least initially in the first six months but showed clear benefit after six months.

Five points in TRANSCEND deserve comment. First, the finding that telmisartan did not reduce the primary composite outcome but reduced the secondary composite outcome that excluded heart failure should be interpreted with caution. The population was especially selected to exclude not only ACE-intolerant patients but also patients with heart failure, and few had left ventricular hypertrophy. Selection may have excluded patients at higher risk and those likely to show benefit for heart failure. Hospitalization for heart failure was low for telmisartan and placebo (4.5% versus 4.3%), and any heart failure event was also low (6.5% versus 6.6%). Although many previous randomized clinical trials established that ACE inhibitorsCitation42,Citation45 and ARBsCitation56,Citation59,Citation61,Citation95 reduce heart failure hospitalization, the patients in those studies were at higher risk for heart failure or left ventricular hypertrophy. Other studies with ACE inhibitorsCitation48,Citation96 and ARBsCitation97 in low-risk patients did not show a decrease in heart failure hospitalization.Citation48,Citation96 In ONTARGET, heart failure hospitalization rates were similar for telmisartan and ramipril (4.6% versus 4.1%). In TRANSCEND, rates of myocardial infarction were also lower than in HOPE (1.09% versus 3.06% per year). Thus, the TRANSCEND population was altogether a lower risk group for heart failure.

Second, the authors suggest that a similar lack of benefit in the primary composite outcome as in TRANSCEND was found in the ProFESS (Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes) study comparing telmisartan with placebo over 2.5 years in patients with recent stroke.Citation16,Citation17,Citation97 They show, in a prespecified analysis of the combined data of the two trials, a reduction in the primary composite outcome after six months (9.3 versus 10.8%; P < 0.001) but not before six months (3.8% versus 3.4%; P = 0.074).Citation17 This finding suggests that prolonged therapy is needed for the heart failure benefit to manifest in that low-risk population.

Third, because HOPE preceded ONTARGET and TRANSCEND by over five years, this may have influenced background therapies in both the treatment and placebo groups. Thus, statin use was higher in TRANSCEND than in previous trials.Citation17 Higher diuretic and beta-blocker use may have impacted on heart failure, and higher antiplatelet use may have impacted on stroke.

Fourth, even in the population with low heart failure risk in TRANSCEND, the rate of myocardial infarction was lower with telmisartan versus placebo (3.9% versus 5.0%; P = 0.059) and similar to that with the ACE inhibitor in ONTARGET (4.8% versus 5.2%),Citation15 suggesting that the previously voiced concern with ARB useCitation51,Citation98 did not apply in these patients. The lower rate of stroke in TRANSCEND was not statistically significant (3.8% versus 4.6%; P = 0.136) but the secondary composite outcome, including stroke, was significantly lower (13.0% versus 14.8%; P = 0.048). This beneficial effect of an ARB on cerebrovascular events is consistent with other reports.Citation15,Citation59 Fifth, an important finding is that even patients who experienced angioneurotic edema and other adverse effects on ACE inhibitors tolerated telmisartan.

Telmisartan and risk of stroke in ProFESS

Previous studies showed that ACE inhibitors and ARBs after remote stroke are beneficial. PROGRESS (the Perindopril Protection against Recurrent Stroke Study) showed lowering of blood pressure in patients with substantial elevation using an ACE inhibitor and diuretic reduced the risk of recurrent stroke.Citation99 HOPE showed that an ACE inhibitor reduces the rate of stroke in patients with previous cardiovascular events or high-risk diabetes despite mild lowering of blood pressure.Citation3 The ARB, eprosartan, reduced recurrent stroke compared with a calcium channel blocker despite similar blood pressure reduction.Citation100 The ARB, candesartan, given early after a stroke reduced rates of death despite no blood pressure reduction.Citation101

The ProFESS studyCitation16 compared telmisartan 80 mg daily (n = 10,146) with placebo (n = 10,186) initiated early after an ischemic stroke, less than 90 days before randomization. Patients were aged 50 years or older, and mean ages were similar (telmisartan 66.1 ± 8.6 years, placebo 66.2 ± 8.6 years). The mean interval from stroke was 15 days. Baseline mean blood pressure averaged 144.1/83.8 mmHg for the two groups. The mean follow-up was 2.5 years. The data showed that telmisartan did not significantly lower the rate of recurrent stroke (8.7% versus 9.2%; P = 0.23), major cardiovascular events (13.5% versus 14.4%; P = 0.11), or new-onset diabetes (1.7% versus 2.1%; P = 0.10). The reasons for the lack of benefit of telmisartan in that study are not clear. As suggested by the authors, the effect of telmisartan may be time-dependent because the 2.5 years was shorter compared with HOPE (4.5 years) and PROGRESS (4.0 years) which showed benefit. The lack of effect on new-onset diabetes is not consistent with previous studies that showed reduced risk of diabetes with ACE inhibitors and ARBs.Citation102,Citation103 In addition, the PPARγ activity of telmisartan should have resulted in benefit. However, the only large trial with diabetes as the primary outcome did not find significant benefit with ramipril,Citation96 suggesting that other factors may be involved.

The ProFESS trial also compared the efficacy of prophylactic treatment using aspirin 25 mg daily plus extendedrelease dipyridamole 200 mg twice daily (n = 10,181) versus clopidogrel 75 mg daily (n = 10,151) and either telmisartan 80 mg daily (n = 10,146) or placebo (n = 10,186) on reduction of disability and recurrent strokesCitation97 in patients with ischemic stroke. In this study too, the data did not show improvement in functional or cognitive outcome comparing the two anti-platelet treatments or telmisartan versus placebo.Citation97

Telmisartan and left ventricular hypertrophy

ONTARGET and TRANSCEND also provided important new data on the effect of telmisartan on left ventricular hypertrophy in high-risk patients without heart failure.Citation15 At entry, the prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy based on electrocardiograms in the two cohorts was 12.4% and 12.7%, respectively. Mean age was 66–67 years. In the ACE inhibitor-intolerant patients of TRANSCEND, telmisartan reduced the prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy (P = 0.0017) compared with placebo at two years (10.5% versus 12.7%) and five years (9.9% versus 12.8%). Importantly, telmisartan suppressed new-onset left ventricular hypertrophy (P = 0.0001) although left ventricular hypertrophy regression was similar. In the ACE inhibitortolerant patients of ONTARGET, left ventricular hypertrophy prevalence was lower with both telmisartan (P = 0.07) and the combination (P = 0.12) compared with ramipril alone, although the differences were not significant. Interestingly, new onset left ventricular hypertrophy was associated with a higher risk of the primary outcome during follow-up. Taken together, telmisartan was more effective than placebo in reducing left ventricular hypertrophy, and new onset left ventricular hypertrophy was reduced by 37%. However, combination of telmisartan with ramipril was not superior to ramipril alone.

Eight points deserve mention. First, the placebo group received intensive therapy but no renin-angiotensin system-blocking drugs. Second, the telmisartan-induced decrease in left ventricular hypertrophy over placebo in TRANSCEND did not translate into decrease in heart failure, and the telmisartan-induced greater decrease in left ventricular hypertrophy over ramipril in ONTARGET did not affect outcome. Third, the lack of difference in left ventricular hypertrophy regression despite a significant decrease in new-onset left ventricular hypertrophy with telmisartan versus placebo in TRANSCEND may be due to the modest decrease in blood pressure with telmisartan. Fourth, the prognostic value of left ventricular hypertrophy regression may be reduced in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy and diabetes compared with those with left ventricular hypertrophy but no diabetes. Fifth, it was unclear why the lower prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy with telmisartan versus ramipril was not statistically significant when other studies showed comparable left ventricular hypertrophy regression with ACE inhibitors and ARBs.Citation104 Due to cost, the study used electrocardiographic criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy rather than echocardiographic left ventricular mass. However, a substudy of 297 ONTARGET patients using magnetic resonance imaging at baseline and at two years showed no left ventricular hypertrophy in the majority at baseline, but a similar decrease in left ventricular mass in all three groups.Citation105

Sixth, when left ventricular hypertrophy is present at baseline, greater left ventricular hypertrophy regression with an ARB than an ACE inhibitor may result from enhanced AT2 receptor activation during AT1 receptor blockade.Citation44 This effect may be further amplified in hypertrophic hearts that have AT2 receptor upregulation, which leads to increased antiproliferative and antifibrotic effects (see ) that oppose AT1 receptor stimulation of hypertrophy and remodeling.

Seventh, the reason why combination therapy showed statistically nonsignificant lower left ventricular hypertrophy prevalence than with ramipril alone is unclear. It is possible that a decline in renal function with combined renin-angiotensin system inhibition blunted the decrease in left ventricular hypertrophy.Citation106 It is also possible that decreased angiotensin II stimulation of AT2 receptors during ACE inhibition limited the decrease in left ventricular hypertrophy. Eighth, the finding of increased risk of the primary outcome with left ventricular hypertrophy is consistent with HOPE, which showed that left ventricular hypertrophy by electrocardiographic voltage criteria was an independent predictor of outcome in high-risk patients. In addition, subendocardial ischemia associated with concentric left ventricular hypertrophy in the presence or absence of coronary disease, may also increase risk.

Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials on telmisartan in hypertension

A recent meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of telmisartan versus ACE inhibitors for patients with hypertension (mean age 40–75 years) showed that telmisartan provides superior blood pressure control, with fewer adverse effects and better tolerability.Citation107

Conclusion

The totality of the evidence from the two comparative megatrials, ONTARGET and TRANSCEND, and other studies suggest that the ARB, telmisartan, produces benefits beyond blood pressure reduction in older adult and younger elderly patients with vascular disease or high-risk diabetes that equal those of the ACE inhibitor, ramipril. Because telmisartan is equally effective and better tolerated than ramipril, this is an advantage for compliance in elderly patients. Thus, telmisartan appears to be an attractive alternative to an ACE inhibitor or a preferred ARB in ACE-intolerant patients. The finding of a greater blood pressure reduction with telmisartan suggests the need for careful dose titration and blood pressure monitoring in high-risk elderly patients, especially in view of age-related changes. The only small trial of telmisartan in elderly patients used careful dose titration and blood pressure monitoring, and showed effective blood pressure control. The possibility that the partial PPARγ activity of telmisartan might confer added benefits in highrisk elderly patients with diabetes is potentially important and needs clinical verification. The finding of increased adverse effects without added benefit with the combination of full-dose telmisartan and ramipril suggests that ARB–ACE inhibitor combinations should be either avoided or used with extreme caution in high-risk elderly patients. The potential importance of additional benefits of telmisartan beyond renin-angiotensin system inhibition on cardiovascular risk and new-onset diabetes deserves further study in carefully designed randomized clinical trials in elderly patients aged >65 years, >75 years, and >85 years, as well as nonelderly subjects.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by Grant # IAP99003 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Ottawa, Ontario.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- Lloyd-JonesDAdamsRJBrownTMHeart Disease and Stroke Statistics – 2010. Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics SubcommitteeCirculation20101217e46e21520019324

- YusufSSleightPPogueJBoschJDaviesRDagenaisGThe Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patientsN Engl J Med2000342314515310639539

- Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study InvestigatorsEffects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: Results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudyLancet2000355920025325910675071

- ChobanianAVBakrisGLBlackHRJoint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood PressureHypertension20034261206125214656957

- ChobanianAVBakrisGLBlackHRNational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 reportJAMA2003289192560257212748199

- RosendorffCBlackHRCannonCPAmerican Heart AssociationCouncil for High Blood Pressure Research; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and PreventionCirculation20071152127612788

- ManciaGde BackerGDominiczakA2007Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Eur Heart J200728121462153617562668

- CalhounDAJonesDTextorSResistant hypertension: Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure ResearchHypertension20085161403141918391085

- BensonSCPershadsinghHAHoCIIdentification of telmisartan as a unique angiotensin II receptor antagonist with selective PPARgamma-modulating activityHypertension2004435993100215007034

- VitaleCMercuroGCastiglioniCMetabolic effect of telmisartan and losartan in hypertensive patients with metabolic syndromeCardiovasc Diabetol2005461315892894

- ScaleraFMartens-LobenhofferJBukowskaALendeckelUTägerMBode-BögerSMEffect of telmisartan on nitric oxide – asymmetrical dimethylarginine system: Role of angiotensin II type 1 receptor gamma and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma signaling during endothelial agingHypertension200851369670318250362

- SaitohYHongweiWUenoHMizutaMNakazatoMTelmisartan attenuates fatty-acid-induced oxidative stress and NAD(P)H oxidase activity in pancreatic beta-cellsDiabetes Metab200935539239719713141

- JungADKimWParkSHThe effect of telmisartan on endothelial function and arterial stiffness in patients with essential hypertensionKorean Circ J200939518018419949576

- SinghSLokeYKFurbergCDThiazolidinediones and heart failure: A teleo-analysisDiabetes Care20073082148215317536074

- YusufSTeoKKPogueJONTARGET InvestigatorsTelmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular eventsN Engl J Med2008358151547155918378520

- YusufSDienerHCSaccoRLTelmisartan to prevent recurrent stroke and cardiovascular eventsNew Engl J Med2008359121225123718753639

- YusufSTeoKAndersonCTelmisartan Randomised AssessmeNt Study in ACE iNtolerant subjects with cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: A randomised controlled trialLancet200837296441174118318757085

- VerdecchiaPSleightPManciaGONTARGET/TRANSCEND InvestigatorsEffects of telmisartan, ramipril, and their combination on left ventricular hypertrophy in individuals at high vascular risk in the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global End Point Trial and the Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular DiseaseCirculation2009120141380138919770395

- KarlbergBELinsLEHermanssonKEfficacy and safety of telmisartan, a selective AT1 receptor antagonist, compared with enalapril in elderly patients with primary hypertension. TEES Study GroupJ Hypertens199917229330210067800

- NakayamaTMasubuchiYKawauchiKBeneficial effect of beraprost sodium plus telmisartan in the prevention of arterial stiffness development in elderly patients with hypertension and cerebral infarctionProstaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids2007309634

- AsmarRGossePTopouchianJN’telaGDudleyAShepherdGLEffects of telmisartan on arterial stiffness in type 2 diabetes patients with essential hypertensionJ Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst20023317618012563568

- FormosaVBellomoAIoriAThe treatment of hypertension with telmisartan in the sphere of circadian rhythm in metabolic syndrome in the elderlyArch Gerontol Geriatr200949Suppl 19510119836621

- JugduttBIAging and remodeling during healing of the wounded heart: Current therapies and novel drug targetsCurr Drug Targets20089432534418393826

- JugduttBIAging and heart failure: Changing demographics and implications for therapy in the elderlyHeart Fail Rev201015540140520364319

- GoldbergRJMcCormickDGurwitzJHAge-related trends in short- and long-term survival after acute myocardial infarction: A 20-year population-based perspective 1975–1995Am J Cardiol19988211131113179856911

- DavisBRVogtTFrostPHRisk factors for stroke and type of stroke in persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program Cooperative Research GroupStroke1998297133313409660383

- WolfPAD’AgostinoRBBelangerAJKannelWBProbability of stroke: A risk profile from the Framingham StudyStroke19912233123182003301

- WhiteHDSimesRJAndersonNEPravastatin therapy and the risk of strokeN Engl J Med2000343531732610922421

- YusufSHawkenSOunpuuSINTERHEART Study InvestigatorsEffect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control studyLancet2004364943893795215364185

- JelaniAJugduttBISTEMI and heart failure in the elderly: Role of adverse remodelingHeart Fail Rev201015551352120549342

- WolfPAD’AgostinoRBO’NealMASecular trends in stroke incidence and mortality. The Framingham StudyStroke19922311155115551440701

- TurnbullFBlood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ CollaborationEffects of different blood-pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: Results of prospectively-designed overviews of randomised trialsLancet200336293951527153514615107

- TehraniFPhanAChienCVMorrisseyRPRafiqueAMSchwarzERValue of medical therapy in patients >80 years of age with heart failure and preserved ejection fractionAm J Cardiol2009103682983319268740

- JugduttBIHeart failure in the elderly: Advances and challengesExpert Rev Cardiovasc Ther20108569571520450303

- KannelWBMcGeeDLDiabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham studyJAMA19792411920352038430798

- WingardDLBarrett-ConnorEHeart disease and diabetesHarrisMJCowieCCSternMSBoykoEJReiberGEBennettPHDiabetes in America2nd edWashington, DCNational Institutes of Health1995

- GuKCowieCCHarrisMIDiabetes and decline in heart disease mortality in US adultsJAMA1999281141291129710208144

- FowlerMJMicrovascular and macrovascular complications of diabetesClin Diabetes20082627782

- LonnEMYusufSJhaPEmerging role of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in cardiac and vascular protectionCirculation1994904205620697923694

- The SOLVD InvestigatorsEffect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failureN Engl J Med199132552933022057034

- PfefferMABraunwaldEMoyéLAEffect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. The SAVE InvestigatorsN Engl J Med1992327106696771386652

- FoxKMThe EURopean trial On reduction of cardiac events with Perindopril in stable coronary Artery disease InvestigatorsEfficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the EUROPA study)Lancet2003362938678278813678872

- PittBO’NeillBFeldmanRQUIET Study GroupThe QUinapril Ischemic Event Trial (QUIET): Evaluation of chronic ACE inhibitor therapy in patients with ischemic heart disease and preserved left ventricular functionAm J Cardiol20018791058106311348602

- BraunwaldEDomanskiMJFowlerSEPEACE Trial InvestigatorsAngiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition in stable coronary artery diseaseN Engl J Med200336220782788

- DagenaisGRPogueJFoxKSimoonsMLYusufSAngiotensin-converting- enzyme inhibitors in stable vascular disease without left ventricular systolic dysfunction or heart failure: a combined analysis of three trialsLancet2006368953558158816905022

- LewisEJHunsickerLGBainRPRohdeRDThe effect of angiotensin-converting- enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The Collaborative Study GroupN Engl J Med199332920145614628413456

- BoschJLonnEPogueJArnoldJMDagenaisGRYusufSHOPE/HOPE-TOO Study InvestigatorsLong-term effects of ramipril on cardiovascular events and on diabetes: Results of the HOPE study extensionCirculation200511291339134616129815

- PatelAADVANCE Collaborative GroupEffects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): A randomised controlled trialLancet2007370959082984017765963

- JugduttBIValsartan in the treatment of heart attack survivorsVasc Health Risk Manag20062212513817319456

- KjeldsenSELylePATershakovecAMTargeting the renin-angiotensin system for the reduction of cardiovascular outcomes in hypertension: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockersExpert Opin Emerg Drugs200510472974516262560

- StraussMHHallASAngiotensin receptor blockers may increase risk of myocardial infarction: Unraveling the ARB-MI paradoxCirculation2006114883885416923768

- CampbellDJKrumHEslerMDLosartan increases bradykinin levels in hypertensive humansCirculation2005111331532015655136

- McKelvieRSYusufSPericakDComparison of candesartan, enalapril, and their combination in congestive heart failure: Randomized evaluation of strategies for left ventricular dysfunction (RESOLVD) pilot study. The RESOLVD Pilot Study InvestigatorsCirculation1999100101056106410477530

- TikkanenIOmvikPJensenHAComparison of the angiotensin II antagonist losartan with the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor enalapril in patients with essential hypertensionJ Hypertens19951311134313518984133

- HolwerdaNJFogariRAngeliPValsartan, a new angiotensin II antagonist for the treatment of essential hypertension: Efficacy and safety compared with placebo and enalaprilJ Hypertens1996149114711518986917

- ChanPTomlinsonBHuangTYKoJTLinTSLeeYSDouble-blind comparison of losartan, lisinopril, and metolazone in elderly hypertensive patients with previous angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced coughJ Clin Pharmacol19973732532579089428

- GrangerCBMcMurrayJJYusufSCHARM Investigators and CommitteesEffects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting- enzyme inhibitors: The CHARM-Alternative trialLancet2003362938677277613678870

- CohnJNTognoniGfor the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial InvestigatorsA randomized trial of angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failureN Engl J Med2001345231667167511759645

- McMurrayJJOstergrenJSwedbergKCHARM Investigators and CommitteesEffects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function taking angiotensin-converting- enzyme inhibitors: The CHARM-Added trialLancet2003362938676777113678869

- DahlofBDevereuxRBKjeldsenSELIFE Study GroupCardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): A randomised trial against atenololLancet20023599311995100311937178

- DicksteinKKjekshusJOPTIMAAL Steering Committee of the OPTIMAAL Study GroupEffects of losartan and captopril on mortality and morbidity in high-risk patients after acute myocardial infarction: The OPTIMAAL randomised trial. Optimal Trial in Myocardial Infarction with Angiotensin II Antagonist LosartanLancet2002360933575276012241832

- PfefferMAMcMurrayJJVelazquezEJValsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial InvestigatorsValsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or bothN Engl J Med2003349201893190614610160

- VolpeMManciaGTrimarcoBAngiotensin II receptor blockers and myocardial infarction: Deeds and misdeedsJ Hypertens200523122113211816269950

- RiesUJMihmGNarrB6-Substituted benzimidazoles as new nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonists: Synthesis, biological activity, and structure-activity relationshipsJ Med Chem19933625404040518258826

- SmithDHGNeutelJMMorgensternPOnce-daily telmisartan compared with enalapril in the treatment of hypertensionAdv Ther199815229240

- NeutelJMSmithDHGDose response and antihypertensive efficacy of the AT1 receptor antagonist telmisartan in patients with mild to moderate hypertensionAdv Ther199815206217

- LarsenPDMartinJLPolypharmacy and elderly patientsAORN J19996936192262562762811957456

- JonesBADecreasing polypharmacy in clients most at riskAACN Clin Issues1997846276349392719

- BurrellLMJohnstonCIAngiotensin II receptor antagonists. Potential in elderly patients with cardiovascular diseaseDrugs Aging19971064214349205848

- PicardFAuwerxJPPAR (gamma) and glucose homeostasisAnnu Rev Nutr20022216719712055342

- WalczakRTontonozPPPARadigms and PPARadoxes: Expanding roles for PPARgamma in the control of lipid metabolismJ Lipid Res200243217718611861659

- WakinoSLawREHsuehWAVascular protective effects by activation of nuclear receptor PPAR gammaJ Diabetes Complications2002161464911872366

- HsuehWALawRThe central role of fat and effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma on progression of insulin resistance and cardiovascular diseaseAm J Cardiol.2003924A3J9J

- SchiffrinELAmiriFBenkiraneKIglarzMDiepQNPeroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: Vascular and cardiac effects in hypertensionHypertension200342466466812874098

- KotchenTAAttenuation of hypertension by insulin-sensitizing agentsHypertension19962822192238707385

- VermaSBhanotSArikawaEYaoLMcNeillJHDirect vasodepressor effects of pioglitazone in spontaneously hypertensive ratsPharmacology19985617169467183

- BuchananTAMeehanWPJengYYBlood pressure lowering by pioglitazone. Evidence for a direct vascular effectJ Clin Invest19959613543607615805

- NestoRWBellDBonowROThiazolidinedione use, fluid retention, and congestive heart failure: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association and American Diabetes AssociationDiabetes Care200427125626314693998

- ShiomiTTsutsuiHHayashidaniSPioglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist, attenuates left ventricular remodeling and failure after experimental myocardial infarctionCirculation2002106243126313212473562

- CaoZYePLongCEffect of pioglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist, on ischemia-reperfusion injury in ratsPharmacology200779318419217356310

- YueTLChenJBaoWIn vivo myocardial protection from ischemia/reperfusion injury by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist rosiglitazoneCirculation2001104212588259411714655

- LygateCAHulbertKMonfaredMThe PPARgamma-activator rosiglitazone does not alter remodeling but increases mortality in rats post-myocardial infarctionCardiovasc Res200358363263712798436

- GrahamDJOuellet-HellstromRMaCurdyTERisk of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and death in elderly Medicare patients treated with rosiglitazone or pioglitazoneJAMA2010304441141820584880

- ZhangHZhangAKohanDENelsonRDGonzalezFJYangTCollecting duct-specific deletion of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma blocks thiazolidinedione-induced fluid retentionProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2005102269406941115956187

- ParhoferKGMünzelFKreklerMEffect of the angiotensin receptor blocker irbesartan on metabolic parameters in clinical practice: The DO-IT prospective observational studyCardiovasc Diabetol200763618042288

- BrennerBMCooperMEde ZeeuwDRENAAL Study InvestigatorsEffects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathyN Engl J Med20013451286186911565518

- NaitoTMaLJYangHAngiotensin type 2 receptor actions contribute to angiotensin type 1 receptor blocker effects on kidney fibrosisAm J Physiol Renal Physiol20102983F683F69120042458

- BarnettAPreventing renal complications in type 2 diabetes: Results of the diabetes exposed to telmisartan and enalapril trialJ Am Soc Nephrol.2006174 Suppl 2S132S13516565237

- PhillipsCOKashaniAKoDKFrancisGKrumholzHMAdverse effects of combination angiotensin II receptor blockers plus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for left ventricular dysfunction: A quantitative review of data from randomized clinical trialsArch Intern Med2007167181930193617923591

- JugduttBIMyocardial salvage by intravenous nitroglycerin in conscious dogs: Loss of beneficial effect with marked nitroglycerin-induced hypotensionCirculation19836836736846409447

- JugduttBIWarnicaJWIntravenous nitroglycerin therapy to limit myocardial infarct size, expansion, and complications. Effect of timing, dosage, and infarct locationCirculation19887849069193139326

- JugduttBIWarnicaJWTolerance with low dose intravenous nitroglycerin therapy in acute myocardial infarctionAm J Cardiol198964105815872506751

- JugduttBIIntravenous nitroglycerin unloading in acute myocardial infarctionAm J Cardiol19916814D52D63

- CruickshankJMThorpJMZachariasFJBenefits and potential harm of lowering high blood pressureLancet1987185335815842881129

- JuliusSKjeldsenSEWeberMfor the VALUE trial groupOutcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: The VALUE randomised trialLancet200436394262022203115207952

- BoschJYusufSGersteinHCDREAM Trial InvestigatorsEffect of ramipril on the incidence of diabetesN Engl J Med2006355151551156216980380

- DienerHCSaccoRLYusufSPrevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes (PRoFESS) study groupEffects of aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel and telmisartan on disability and cognitive function after recurrent stroke in patients with ischaemic stroke in the Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes (PRoFESS) trial: A double-blind, active and placebo-controlled studyLancet Neurol200871087588418757238

- VermaSStraussMAngiotensin receptor blockers and myocardial infarctionBMJ200432974771248124915564232

- PROGRESS Collaborative GroupRandomised trial of a perindopril- based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attackLancet2001359928710331041

- SchraderJLüdersSKulschewskiAMOSES Study GroupMorbidity and Mortality After Stroke, eprosartan compared with nitrendipine for secondary prevention: Principal results of a prospective randomized controlled study (MOSES)Stroke20053661218122615879332

- SchraderJLüdersSKulschewskiAAcute Candesartan Cilexetil Therapy in Stroke Survivors Study GroupThe ACCESS Study: Evaluation of Acute Candesartan Cilexetil Therapy in Stroke SurvivorsStroke20033471699170312817109

- YusufSGersteinHHoogwerfBHOPE Study InvestigatorsRamipril and the development of diabetesJAMA2001286151882188511597291

- ElliottWJMeyerPMIncident diabetes in clinical trials of antihypertensive drugs: A network meta-analysisLancet2007369955720120717240286

- CuspidiCMuiesanMLValagussaLCATCH investigatorsComparative effects of candesartan and enalapril on left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with essential hypertension: The candesartan assessment in the treatment of cardiac hypertrophy (CATCH) studyJ Hypertens200220112293230012409969

- CowanBPYoungAAAndersonCLeft ventricular mass and volume with telmisartan, ramipril, or combination in patients at high risk for vascular events: The Cardiac MRI sub-study to ONTARGETAm J Cardiol2009104111484148919932779

- MannJFSchmiederREMcQueenMONTARGET investigatorsRenal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trialLancet2008372963854755318707986

- ZouZXiGLYuanHBZhuQFShiXYTelmisartan versus angio-tension-converting enzyme inhibitors in the treatment of hypertension: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsJ Hum Hypertens200923533934918987649