Abstract

Objective

The recognition of the limits between normal and pathological aging is essential to start preventive actions. The aim of this paper is to compare the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) and language tests to distinguish subtle differences in cognitive performances in two different age groups, namely young adults and elderly cognitively normal subjects.

Method

We selected 29 young adults (29.9±1.06 years) and 31 older adults (74.1±1.15 years) matched by educational level (years of schooling). All subjects underwent a general assessment and a battery of neuropsychological tests, including the Mini Mental State Examination, visuospatial learning, and memory tasks from CANTAB and language tests. Cluster and discriminant analysis were applied to all neuropsychological test results to distinguish possible subgroups inside each age group.

Results

Significant differences in the performance of aged and young adults were detected in both language and visuospatial memory tests. Intragroup cluster and discriminant analysis revealed that CANTAB, as compared to language tests, was able to detect subtle but significant differences between the subjects.

Conclusion

Based on these findings, we concluded that, as compared to language tests, large-scale application of automated visuospatial tests to assess learning and memory might increase our ability to discern the limits between normal and pathological aging.

Introduction

The increasing rate of chronic neurodegenerative diseases in the elderly, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), is a global phenomenon. Because AD occurs in both developed and developing countries and contributes to 70% of all reported dementias,Citation1 it has become a driving force in aging research. To reduce its impact on the public health budget,Citation2,Citation3 early diagnosis and prevention of cognitive decline may be essential.Citation4 In this context, the distinction between individuals who will maintain adequate cognitive function into their later years and those on a trajectory to dementia is a fundamental question being pursued.Citation5 It is essential to establish accurate and sensitive tools for assessing the cognitive function and the neuropsychological screening of the aging population.

The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)Citation6 is the most widely used cognitive screening tool in both clinical settings and epidemiological studies.Citation7 However, the MMSE is unable to detect subtle declines in cognitive aging.Citation8 It exhibits a ceiling effect in healthy young or older adults and a floor effect in the oldest older adults.Citation9,Citation10 Additionally, correcting the MMSE score for educational level influences these effects.Citation7 In contrast, evidence indicates that performances on tests of episodic memory are significantly lower among mildly impaired but non-demented individuals, who will subsequently fulfill criteria for AD over time.Citation11–Citation17 In addition, it has been reported that lower performances on language memory tests may predict cognitive decline. Indeed, semantic memory,Citation17 word and story recall, object naming, and Boston Naming Test,Citation18,Citation19 as well as semantic, verb, and letter fluencies,Citation20 may be predictive for future dementia in aged individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Moreover, automated semantic indices or latent profile assessment based on patterns of cognition from large samples may distinguish preclinical phenotypes for AD.Citation21,Citation22 Finally, automated visuospatial learning and memory tests have also shown predictive value regarding future dementia of the Alzheimer type.Citation23–Citation25 Compared with traditional standard methods, automated computer tests minimize floor and ceiling effects, standardize the format of application, and measure the speed and accuracy of responses with greater sensitivity.Citation26 Among the automated test batteries currently in use, the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) is frequently applied to discriminate between cognitively healthy aged adults and those in the preclinical stages of future dementia.Citation26,Citation27 For example, baseline results from non-demented patients who underwent the paired-associates learning test from the CANTAB were found to correlate with preclinical AD.Citation17,Citation23,Citation28,Citation29 However, less has been done to compare the resolution of the CANTAB’s automated neuropsychological tests with standard neuropsychological tests, in which a few automated scores and normative comparison of raw test scores are available across lifespan, and test/retest studies reported significant variability across administrations.Citation27,Citation30,Citation31 CANTAB is a nonverbal visuospatial stimulus battery that employs touchscreen technology to obtain nonverbal responses from participants. It is quite adequate for cognitive assessment across cultures, in both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies, with minimal interference of the researcher or clinician during data acquisition.Citation32

Thus, in this study, we have carried out an exploratory investigation to assess the performance of selected CANTAB neuropsychological tests by adult (20–40 years old) and aged (≥65 years old) individuals to distinguish intragroup episodic memory performances.

To that end, all individuals were preliminarily submitted to MMSE, and cognitively healthy individuals were selected for language and CANTAB visuospatial memory tests. Cluster and discriminant analyses were applied to the results of each test in isolation or in combination to identify the best choice to distinguish intragroup cognitive performances. Finally, we tested the hypothesis that CANTAB indices would correlate with performances on language tests that assessed the corresponding cognitive domains.

Thus, we address two simple questions: 1) To what extents do language and CANTAB tests, in isolation or in combination, distinguish possible clusters of cognitive performances in young adults and elderly normal subjects? 2) What is the relationship between performances on language tests and CANTAB tests that assess corresponding cognitive domains?

Methods

Study participants

We performed a cross-sectional neuropsychological evaluation of 60 individuals grouped as older aged (74.1±1.15 years, n=31) and young adults (29.9±1.06 years, n=29) with no history of head trauma, stroke, primary depression, or chronic alcoholism. All participants had normal cognitive performance when administered the MMSE, with the necessary adjustments for education level according to the criteria for the Brazilian population with the following cutoffs: illiterate, 13 points; 1–7 years of schooling, 18 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 26 points.Citation33 All patients who met these criteria were assessed with selected language, visuospatial learning, and memory tests, as well as the MMSE. The local Research Ethics Committee (protocol No 3955/09) approved this study, and all ethical recommendations in research involving human subjects were observed.

Cognitive evaluation

We applied the MMSECitation6,Citation33,Citation34 followed by language tests on the same day. The CANTAB test was administered separately on another day. Trained investigators administered these tests in an environment with adequate lighting and reduced noise conditions.

Language assessment

The Boston Naming Test (shortened version) was administered and analyzed according to parameterized data for Brazil,Citation35,Citation36 adopting a cutoff equivalent to the correct naming of 12 of 15 possible figures.

Semantic (SVF) and Phonological Verbal Fluency (PVF) tests were administered and computed using the following cutoffs: <9 points for illiterate individuals, <12 points for individuals with 1–7 years of schooling, and <13 points for individuals with ≥8 years of schooling.Citation37

The Test of Narrative “Cookie Theft” was evaluated using previously published criteria on the information content of the image, including the number of key concepts, narrative efficiency, number of units of information, the total number of words, and the concision ratio (ratio of information units to the total number of words).Citation38,Citation39

The Montréal d’Evaluation de la Communication is a battery comprised of the following tests: Metaphors (explanation and alternatives), Direct Speech Acts and Indirect Speech Acts (explanation and alternatives), Linguistic and Emotional Prosody, and Narrative Discourse (partial retelling, total retelling, and full text comprehension). The Montréal d’Evaluation de la Communication battery was administered and the performance measured in accordance with guidelines validated for the Brazilian population.Citation40,Citation41

Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery

The CANTAB focuses on three cognitive domains: working memory and planning, attention, and visuospatial memory. Responses are via touchscreen and are largely independent of verbal instruction. An XGA-touch panel 12-inch monitor (Paceblade Slim-book P120; PaceBlade Technology, Hong Kong, People’s Republic of China) was used to present all visuospatial stimuli for testing. The monitor was controlled using CANTAB software (Cambridge Cognition, Cambridge, UK) run on the slim-book. All study participants were assessed individually. We started with a motor screening task which introduced the CANTAB touchscreen to the individuals. The motor screening task provides a general assay that tests whether sensorimotor or other difficulties limit the collection of valid data from each participant. After touchscreen adaptation, we selected a number of CANTAB tests as follows: Rapid Visual Information Processing (RVP), Reaction Time (RTI), Paired Associate Learning (PAL), Spatial Working Memory (SWM), and Delayed Matching to Sample (DMS). The RVP measure is sensitive to sustained attention. In this test, a white box appears in the center of the screen with digits from 2–9 in a pseudorandom order at the rate of 100 digits per minute, and the subjects are requested to identify target sequences of three digits and to register responses using the press pad. RTI provides assays of motor and mental response speeds, as well as measures of movement time, reaction time, response accuracy, and impulsivity. This test is divided into five stages that are characterized by increasingly complex chains of responses. PAL assesses visual memory and new learning. In this test, six boxes are displayed on the screen, and they are opened in random order to reveal the contents. One or more of them will contain a pattern. The patterns inside the boxes are then displayed in the middle of the screen one at a time, and the participants must touch the box in which the pattern was originally located. SWM measures the retention and manipulation of visuospatial information. In this test, the participant must search the boxes on the screen to find a blue “token” in each of a number of boxes, and use them to fill an empty column on the right-hand side of the screen; the number of boxes is gradually increased until it is necessary to search eight boxes. DMS assesses forced choice recognition memory for visual patterns, and tests both simultaneous matching and short-term visual memory. In this test, a complex visual pattern (the sample) is shown to the participant, followed by four similar patterns after a short delay. The participant must touch the pattern that exactly matches the sample. For detailed information, see http://www.cambridgecognition.com/clinicaltrials/cantabsolutions/tests

Results

We subjected all test results from all participants to an initial cluster analysis (tree clustering method, Euclidean distances, and complete linkage). Cluster analysis encompasses a number of different classification algorithms applied to a wide variety of research problems.Citation42–Citation45 They are mostly used when one does not have an a priori hypothesis about which objects belong to a specific cluster group. We applied this multivariate statistical procedure to our sample of study participants in combination (young adults + aged subjects) to search for potential groups of distinct cognitive performances. After that, similar procedures were applied to young adult and aged groups in isolation to search for potential subgroups. The performance groups suggested by cluster analysis were further assessed through the performance of a discriminant function analysis using Statistica 7.0 (Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). Discriminant function analysis is used to determine which variables discriminate between two or more naturally occurring groups. The strategy underlying this procedure is to determine whether groups differ with regard to the mean of a variable, and then to use that variable to predict group membership. In the present study, we performed comparisons between matrices of total variances and covariances. These matrices were compared via multivariate F-tests to determine whether there were any significant between-group differences (with regard to all variables).

Neuropsychologial performances across life span: cluster and discriminant analysis

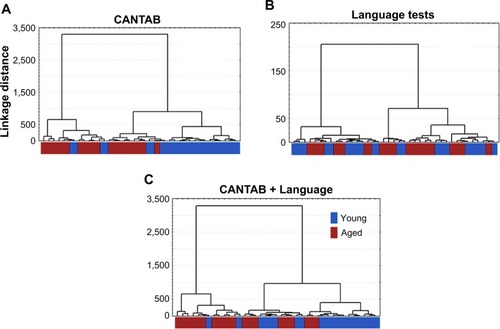

illustrates four dendrograms resulting from cluster analysis applied to isolated or combined neuropsychological test results of the whole sample, including young and older subjects. Note that, compared with all other possibilities of cluster analysis, either in isolation (Language, ) or in combinations of two (CANTAB + Language; ), the cluster analysis applied to CANTAB results () discriminated best between the performances of young adults and older adults.

Figure 1 Dendrograms from cluster analysis applied to isolated or combined neuropsychological test results.

Abbreviation: CANTAB, Cambridge Neuropsychological Tests Automated Battery.

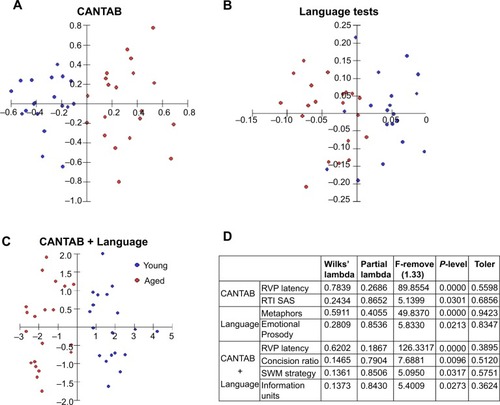

We applied this procedure to determine which neuropsychological tests, isolated or associated, provided the best separation between the performance groups suggested by the cluster analysis. shows the results of probability density (P-values) after discriminant analysis. Note that “latency values” on CANTAB RVP was by far the variable that best contributed to cluster formation, in isolation (P=1.0×10−10) or in combination (CANTAB + Language, P=4×10−12). Although the cluster formation based on isolated language tests did not discriminate between age groups as well as CANTAB in isolation (P=1×10−10), metaphors (P=4×10−8), or emotional prosody (P=0.021), it contributed significantly to cluster formation.

Table 1 Probability density values (P-values) from discriminant analysis to detect which neuropsychological tests best contributed to cluster formation, either in isolation or in combination

shows graphical representations of discriminant analysis to illustrate the best separation between groups. As compared to isolated CANTAB () or Language () isolated tests, discriminant analysis of CANTAB and language tests results in combination () provided the best separation between young and older adult’s performances. However, the CANTAB results better distinguished young and older adults’ performances than language tests. Note that RVP latency, concision ratio, SWM strategy, and information units were the variables that better contributed to cluster formation when combining language and CANTAB test results (). For isolated CANTAB or language tests results, RVP latency and metaphors results, respectively, were by far the variables that best contributed to distinguish young and older adults’ performances ().

Figure 2 Graphic representations of forward stepwise discriminant function analysis based on isolated (A, B) or combined CANTAB and Language (C) tests results.

Abbreviations: CANTAB, Cambridge Neuropsychological Tests Automated Battery; RTI, reaction time; RVP, Rapid Visual Information Processing; SAS, simple accuracy score; SWM, Spatial Working Memory.

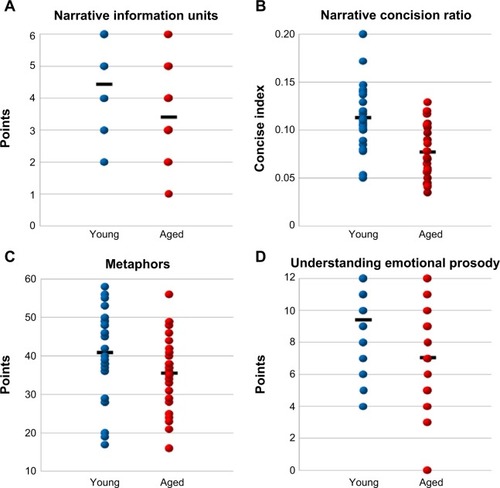

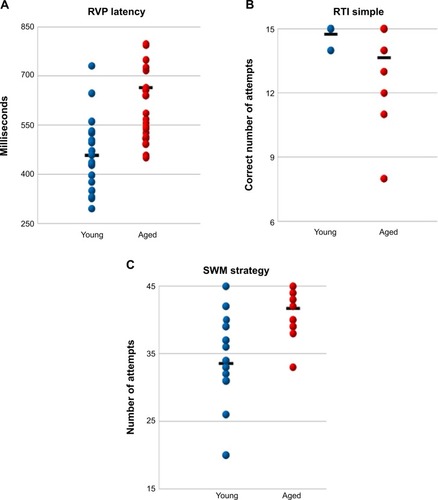

Graphical representations in and illustrate individual performances and mean values of the neuropsychological test results that were indicated by discriminant analysis to be the best predictors for cluster formation. Although the mean values of young and aged adults in these tests differed significantly, the dispersion of individual scores revealed remarkable similarities between some of the young and aged adults’ performances, particularly in the following language tests: information units (4.44±0.2 vs 3.41±0.23, mean ± SEM), metaphors (40.89±2.03 vs 35.58±1.67), and emotional prosody (9.41±0.4 vs 7.06±0.45). These findings suggest that CANTAB tests are able to distinguish subtle differences in cognitive performances inside each group and between groups more accurately.

Figure 3 Graphic representations of mean scores and dispersion from the language test performances of young and older adults.

Notes: Narrative results based on information units (A), concision ratio (B), metaphors (C), and emotional prosody (D) revealed different degrees of dispersion, although the average values of older and young adults’ performances differed significantly. Mean values are indicated by black dots in both young (blue circles) and older (red circles) groups. Note the smaller dispersion in the concision ratio results from the narrative tests.

Figure 4 Graphic representations of mean scores and dispersion from CANTAB performances of young and older adults.

Abbreviations: CANTAB, Cambridge Neuropsychological Tests Automated Battery; RTI, reaction time; RVP, Rapid Visual Information Processing; SWM, Spatial Working Memory.

In addition, the probability of error given correctly from delayed matching to sample (DMS-PEGC) and total errors adjusted from paired associates learning (PAL-TEA) tests results (not illustrated) revealed significant differences (two tailed t-test P<0.05) between young and older adult groups (PEGC =0.13±0.03 vs 0.26±0.02 and TEA =16±1.66 vs 63.75±7.46).

Cluster and discriminant analysis for aged groups

Similar analysis was applied to isolated neuropsychological test results for each age group. CANTAB, but not language tests, distinguished subgroups in the aged group, and the variables that best contributed to the clusters formation were RVP latency (P=0.000009) and RVP A’ (signal detection measure of sensitivity to the target) (P=0.01) and Euclidian distance above 500 units. When applied in combination, CANTAB and language tests did not improve the distinction between subgroups.

Cluster and discriminant analysis for young groups

Language or CANTAB tests were not able to distinguish subgroups in the young group. Indeed, Euclidian distances revealed subgroups much closer to each other (Euclidian distances lower than 300 units).

A correlational matrix was employed to test for possible linear correlations between CANTAB and language assessments. No simple correlations were observed between the test results.

Discussion

In the present work, we investigated to what extent language and CANTAB tests, in isolation or in combination, could distinguish subtle differences in cognitive performances in young adults and elderly normal subjects and whether such performances on those tests correlated with each other. Cluster and discriminant analysis revealed that CANTAB tests could distinguish between the cognitive performances of age groups better than language tests, and no linear correlations were observed between CANTAB and language results. We suggest that the use of large-scale automated visuospatial tests to assess learning and memory from CANTAB improves the signal-to-noise ratio, expanding our ability to define the limits between normal and pathological aging.

CANTAB versus language tests to detect age-related cognitive decline

The decline in cognitive function during human aging is well documented. This decline is apparent from tests of learning and memory, executive functions, attention, and processing speed.Citation30,Citation46 Neurophysiological and neuroanatomical evidence obtained through brain imaging suggests that the earliest brain changes occur in the prefrontal and temporal areas. The prefrontal area involves impairments in executive and planning functions, while the temporal areas involve memory and learning.Citation47,Citation48 In this study, cluster analysis revealed that selected CANTAB tests in isolation provided the best option to distinguish between the performances of the whole sample. In fact, the performances were mostly segregated into three distinct clusters: two dominated mostly by aged subjects and one mostly by young subjects (). Compared with cluster analysis based on isolated CANTAB results, all other dendrograms from both isolated (language tests) and combined tests (CANTAB + Language), revealed a lower degree of segregation.

In the specific case of aging, previous results from CANTAB tests have revealed significant cognitive decline as a function of age, limited to the SWM test (which assesses the frontal lobe) and the PAL test (which evaluates both frontal and the temporal lobe functions).Citation49 Although the CANTAB DMS test also discriminated between the performances of young and older adults (not illustrated), it did not do as well as the PAL and SWM tests. However, because of its selectivity for temporal lobe function, lower performances of older adults on the DMS test suggest that episodic memory is indeed affected by age in our sample. In addition, the lower SWM performance in the group of older adults confirmed previous results using this test, demonstrating a decline in working memory with increasing age.Citation30,Citation50,Citation51 In addition, and more importantly because of their discriminative properties in the cluster analysis, other CANTAB test results (RTI and RVP) were also affected by aging, suggesting that reduced processing speed (which appears to progress linearly with age) is associated with increased latency and reaction time.Citation52

Emotional and linguistic prosody

Although impairments in linguistic and emotional prosody in healthy elderly individuals appear to be largely unrelated to cognitive decline, their integrity may be relevant to explore aging effects related to cognitive appraisal when comparing young versus old adults and measure right hemisphere cognitive decline in senescence.Citation53 In this work, as expected, we did not find any linear correlation between linguistic or emotional prosody scores and all other tests scores. These results are in agreement with othersCitation54–Citation58 which demonstrate that the decline of linguistic and emotional prosody in the elderly is not related to age-related cognitive decline.

Interpretation of the affective state of others with respect to both speech and emotional face recognition is an essential component of normal psychosocial interactions. In agreement with previous reports,Citation54,Citation55,Citation59,Citation60 our findings demonstrate age-related decline in the perception of emotional prosody. As expected, the healthy elderly individuals performed significantly worse than young adults on tasks that assessed the comprehension of affective prosody.

The linguistic prosody test is used to measure the capacity to distinguish declarative statements and questions. Statements are characterized by falling terminal pitch, and questions by rising terminal pitch.Citation60,Citation61 Previous results demonstrated age-related difficulties in interpreting linguistic patterns,Citation56 and the performance of older adults on linguistic tasks with pitch contour patterns was less accurate than that of younger adults, ie, more difficulty identifying questions than statements.Citation60 In agreement with these results, the present work confirms that, on average, young adults perform better than older adults with respect to linguistic prosody assessment. Similar to a previous report,Citation60 older adults had slightly more impaired emotional prosody than linguistic prosody compared with young adults.

Metaphors

Literal lexical-semantic comprehension is always necessary in social communication, but it is not sufficient to guarantee appropriate communication.Citation62 Comprehension of nonliteral implication is often essential to interpret the implicit meaning in a sentence, which is not always expressed explicitly.Citation63 Although no consensus has been obtained regarding the decline in metaphor comprehension with aging,Citation64–Citation69 previous reports have demonstrated that young adults make fewer mistakes in metaphor tests than healthy older adults.Citation70 In agreement with these findings, absolute numbers in the present report indicated that older adults committed an average of 13% more errors on the metaphor test than younger adults. As described for emotional prosody, we detected no correlations between performance on the metaphor test and age-related cognitive decline in the present work.

Another group of language functions was also impaired by age. This finding is indicated by the lower scores of older adults versus younger adults on the Boston Naming Test (reduced version), linguistic prosody, and narrative tests (main concepts, information units, and concision).

Boston Naming Test

The Boston Naming Test is able to assess the degree of difficulty in finding words encountered by healthy elderly individuals, as well as by individuals in the initial stages of dementia.Citation71 Although the results of the confrontational Boston Naming Test (as applied in the present work) are qualitatively affected by the cultural background, particularly with regard to non-English-speaking populations, their quantitative scores are not.Citation72 Thus, as previously described for non-native English speakers,Citation72 our findings using the Boston Naming Test version adapted to speakers of Brazilian PortugueseCitation73 demonstrated significantly lower scores among older adults than among young adults.

Narrative tests

In general discourse, comprehension abilities decline with ageCitation74,Citation75 and appear to be influenced by executive functions.Citation76 Age-related changes have also been reported in the production of discourse, and a picture description task is frequently used to reveal such decline. Nonpathological aging is typically associated with dysfunctions of the prefrontal cortex.Citation77,Citation78 Because discourse production is thought to depend on prefrontal cortical integrity, it has been proposed that the analysis of narrative discourse structure may be a measure of executive function in adults.Citation76 Although we have not yet established cutoff points for the Brazilian population using narrative tests and large samples, we found (as previously described in Ref. Citation79) that, on average, the narrative structure was significantly impaired in older adults compared with young adults. Older adults exhibited lower scores in main concepts, information units, and concision than young adults.

CANTAB versus language tests: limits of comparative analysis

To be reliable, neuropsychological tests must replicate results in a systematic way when subjects are tested repeatedly. To be valid, the tests must be able to identify individuals with the same type of neuroanatomical change, who exhibit similar and consistent test performances for the same cognitive domain and with the same sensitivity. To be specific, the tests must be sensitive to the functional changes of interest, but not to others.Citation49 Because these conditions were met and consistent results were obtained for a number of selected tests intended to assess the prefrontal and temporal lobes,Citation50,Citation51 the CANTAB was considered reliable in assessing the type and degree of functional loss and the specificity of aging-associated changes in the temporal and prefrontal lobes.Citation80,Citation81 Because a large number of individuals were assessed by the CANTAB, it was possible to establish the degree of correlation between the functional demand imposed by the selected tests and the neural areas involved in those functions.Citation49–Citation51

Although we do not yet have a large sample to define the norms and cutoff points for the Brazilian population using the CANTAB, this battery (originally designed to compare monkey and human performancesCitation48,Citation82–Citation84) is largely independent of cultural differences.Citation19,Citation30,Citation84,Citation85 Indeed, our findings are in agreement with a number of previous studies with CANTABCitation27,Citation30,Citation50,Citation51 which confirm age-related cognitive decline in selected tests for both temporal and prefrontal lobe functions. Because the neuropsychological test results from the CANTAB have been validated in many countries with different cultures,Citation30,Citation51,Citation86,Citation87 we suggest that the CANTAB may be an adequate tool for transnational comparative studies of both normal and pathological aging.

However, it is important to mention that the selected CANTAB tests did not include verbal measures. Thus, comparative analysis with the language tests detailed in this paper may have some limitations in the sense that similar cognitive domains in the CANTAB and language tests are not necessarily processed and retrieved using the same subjacent neural networks and mechanisms.Citation88 In addition, possible correlations between CANTAB subtests and traditional paper-and-pencil neuropsychological tests demonstrated modest associations when education and age were controlled for.Citation27 In agreement with these observations, our findings revealed no linear correlation between the results of language and CANTAB tests in the present work.

Finally, it has been suggested that familiarity with the computer interface may influence performance on computerized test batteries;Citation89 however, because the CANTAB does not require any computer/technology knowledge, frequent computer users do not gain any significant operative advantage over users who are unfamiliar with computerized automated tests.Citation90

Although the number of individuals tested in the present study does not encourage generalized conclusions, our exploratory study strongly suggests that the CANTAB test results in isolation may improve the signal-to-noise ratio when distinguishing the performance of subgroups both in young adults and the elderly better than language tests do. Because the language and CANTAB tests assessing corresponding cognitive domains were not linearly correlated, it is important that we increase our sample size in order to be able to confirm and generalize these preliminary observations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Programa Pesquisa para o SUS: gestão compartilhada em saúde (PPSUS) – Ministério da Saúde/Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq)/Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Pará (FAPESPA)/Secretaria de Saúde do Estado do Pará (SESPA) (Grant No 051/2007 and 013/2009); Agência Brasileira da Inovação (FINEP)/Fundação de Amparo e Desenvolvimento da Pesquisa (FADESP) (Grant No 01.04.0043.00); and Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa (PROPESP-UFPA)/Fundação de Amparo e Desenvolvimento da Pesquisa (FADESP).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FratiglioniLDe RonchiDAgüero-TorresHWorldwide prevalence and incidence of dementiaDrugs Aging19991536537510600044

- ZhuCWSanoMEconomic considerations in the management of Alzheimer’s diseaseClin Interv Aging2006114315418044111

- ErnstRLHayJWFennCTinklenbergJYesavageJACognitive function and the costs of Alzheimer disease. An exploratory studyArch Neurol1997546876939193203

- DaffnerKRPromoting successful cognitive aging: a comprehensive reviewJ Alzheimers Dis2010191101112220308777

- WagsterMVCognitive aging research: an exciting time for a maturing field: a postscript to the special issue of neuropsychology reviewNeuropsychol Rev20091952352519943133

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res1975121891981202204

- Franco-MarinaFGarcía-GonzálezJJWagner-EcheagarayFThe mini-mental state examination revisited: ceiling and floor effects after score adjustment for educational level in an aging Mexican populationInt Psychogeriatr201022728119735592

- MarioniREChatfieldMBrayneCMatthewsFEMedical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study GroupThe reliability of assigning individuals to cognitive states using the Mini Mental-State Examination: a population-based prospective cohort studyBMC Med Res Methodol20111112721896187

- BrayneCThe mini-mental state examination, will we be using it in 2001?Int J Geriatr Psychiatry1998132852909658260

- TombaughGCYangSHSwansonRASapolskyRMGlucocorticoids exacerbate hypoxic and hypoglycemic hippocampal injury in vitro: biochemical correlates and a role for astrocytesJ Neurochem1992591371461613495

- BlackerDLeeHMuzikanskyANeuropsychological measures in normal individuals that predict subsequent cognitive declineArch Neurol20076486287117562935

- HowiesonDBDameACamicioliRSextonGPayamiHKayeJACognitive markers preceding Alzheimer’s dementia in the healthy oldest oldJ Am Geriatr Soc1997455845899158579

- SmallGWLa RueAKomoSKaplanAMandelkernMAPredictors of cognitive change in middle-aged and older adults with memory lossAm J Psychiatry1995152175717648526242

- TierneyMCSzalaiJPSnowWGPrediction of probable Alzheimer’s disease in memory-impaired patients: a prospective longitudinal studyNeurology1996466616658618663

- RubinEHStorandtMMillerJPA prospective study of cognitive function and onset of dementia in cognitively healthy eldersArch Neurol1998553954019520014

- ChenPRatcliffGBelleSHCauleyJADeKoskySTGanguliMCognitive tests that best discriminate between presymptomatic AD and those who remain nondementedNeurology2000551847185311134384

- BlackwellADSahakianBJVeseyRSempleJMRobbinsTWHodgesJRDetecting dementia: novel neuropsychological markers of preclinical Alzheimer’s diseaseDement Geriatr Cogn Disord200417424814560064

- BellevilleSGauthierSLepageEKergoatMJGilbertBPredicting decline in mild cognitive impairment: a prospective cognitive studyNeuropsychology201428464365224588699

- WeissbergerGHSalmonDPBondiMWGollanTHWhich neuropsychological tests predict progression to Alzheimer’s disease in Hispanics?Neuropsychology20132734335523688216

- ClarkDGWadleyVGKapurPLexical factors and cerebral regions influencing verbal fluency performance in MCINeuropsychologia2014549811124384308

- PakhomovSVHemmyLSLimKOAutomated semantic indices related to cognitive function and rate of cognitive declineNeuropsychologia2012502165217522659109

- HaydenKMKuchibhatlaMRomeroHRPre-clinical cognitive phenotypes for Alzheimer disease: a latent profile approachAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201422111364137424080384

- FowlerKSSalingMMConwayELSempleJMLouisWJPaired associate performance in the early detection of DATJ Int Neuropsychol Soc20028587111843075

- IachiniIIavaroneASeneseVPRuotoloFRuggieroGVisuospatial memory in healthy elderly, AD and MCI: a reviewCurr Aging Sci20092435920021398

- Juncos-RabadánOPereiroAXFacalDReboredoALojo-SeoaneCDo the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery episodic memory measures discriminate amnestic mild cognitive impairment?Int J Geriatr Psychiatry201429660260924150876

- WildKHowiesonDWebbeFSeelyeAKayeJStatus of computerized cognitive testing in aging: a systematic reviewAlzheimers Dement2008442843719012868

- SmithPJNeedACCirulliETChiba-FalekOAttixDKA comparison of the Cambridge Automated Neuropsychological Test Battery (CANTAB) with “traditional” neuropsychological testing instrumentsJ Clin Exp Neuropsychol20133531932823444947

- SkolimowskaJWesierskaMLewandowskaMSzymaszekASzelagEDivergent effects of age on performance in spatial associative learning and real idiothetic memory in humansBehav Brain Res2011218879321108974

- JunkkilaJOjaSLaineMKarraschMApplicability of the CANTAB-PAL computerized memory test in identifying amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s diseaseDement Geriatr Cogn Disord201234838922922741

- De LucaCRWoodSJAndersonVNormative data from the CANTAB. I: development of executive function over the lifespanJ Clin Exp Neuropsychol20032524225412754681

- LoweCRabbittPTest/re-test reliability of the CANTAB and ISPOCD neuropsychological batteries: theoretical and practical issues. Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery. International Study of Post-Operative Cognitive DysfunctionNeuropsychologia1998369159239740364

- SahakianBJOwenAMComputerized assessment in neuropsychiatry using CANTAB: discussion paperJ R Soc Med1992853994021629849

- BertolucciPHBruckiSMCampacciSRJulianoYThe Mini-Mental State Examination in a general population: impact of educational statusArq Neuropsiquiatr19945217 Portuguese8002795

- MarcopulosBMcLainCAre our norms “normal”? A 4-year follow-up study of a biracial sample of rural elders with low educationClin Neuropsychol200317193312854008

- BertolucciPHFOkamotoIHTonioloJNRamosLRBrukiSMDDesempenho da população brasileira na bateria neuropsicológica do Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD)Rev Psiquiatr Clín1998258083 Portuguese

- BertolucciPHOkamotoIHBruckiSMSivieroMOToniolo NetoJRamosLRApplicability of the CERAD neuropsychological battery to Brazilian elderlyArq Neuropsiquiatr20015953253611588630

- CaramelliPCarthery-GoulartMTPortoCSCharchat-FichmanHNitriniRCategory fluency as a screening test for Alzheimer disease in illiterate and literate patientsAlzheimer Dis Assoc Disord200721656717334275

- Forbes-McKayKEVenneriADetecting subtle spontaneous language decline in early Alzheimer’s disease with a picture description taskNeurol Sci20052624325416193251

- Groves-WrightKNeils-StrunjasJBurnettRO’NeillMJA comparison of verbal and written language in Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Commun Disord20043710913015013729

- FonsecaRPJoanetteYCoteHBrazilian version of the Protocole Montreal d’Evaluation de la Communication (Protocole MEC): normative and reliability dataSpan J Psychol20081167868818988453

- FonsecaRPParenteMACôtéHSkaBJoanetteYIntroducing a communication assessment tool to Brazilian speech therapists: the MAC BatteryPro Fono20082028529119142474

- SteeleGEWellerREQualitative and quantitative features of axons projecting from caudal to rostral inferior temporal cortex of squirrel monkeysVis Neurosci1995127017228527371

- SchweitzerLRenehanWEThe use of cluster analysis for cell typingBrain Res Brain Res Protoc199711001089385054

- Gomes-LealWSilvaGJOliveiraRBPicanco-DinizCWComputer-assisted morphometric analysis of intrinsic axon terminals in the supragranular layers of cat striate cortexAnat Embryol (Berl)200220529130012136259

- RochaEGSantiagoLFFreireMAMCallosal axon arbors in the limb representations of the somatosensory cortex (SI) in the agouti (Dasyprocta primnolopha)J Comp Neurol200750025526617111360

- SliwinskiMBuschkeHCross-sectional and longitudinal relationships among age, cognition, and processing speedPsychol Aging199914183310224629

- NagaharaAHNicolleMMGallagherMAlterations in [3H]-kainate receptor binding in the hippocampal formation of aged Long-Evans ratsHippocampus199332692778394771

- NagaharaAHBernotTTuszynskiMHAge-related cognitive deficits in rhesus monkeys mirror human deficits on an automated test batteryNeurobiol Aging2010311020103118760505

- RabbittPLoweCPatterns of cognitive ageingPsychol Res20006330831611004884

- RobbinsTWJamesMOwenAMA study of performance on tests from the CANTAB battery sensitive to frontal lobe dysfunction in a large sample of normal volunteers: implications for theories of executive functioning and cognitive agingJ Int Neuropsychol Soc199844744909745237

- RobbinsTWJamesMOwenAMSahakianBJMcInnesLRabbittPCambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB): a factor analytic study of a large sample of normal elderly volunteersDementia199452662817951684

- CarriereJSCheyneJASolmanGJSmilekDAge trends for failures of sustained attentionPsychol Aging20102556957420677878

- RossEDMonnotMAffective prosody: what do comprehension errors tell us about hemispheric lateralization of emotions, sex and aging effects, and the role of cognitive appraisalNeuropsychologia201149586687721182850

- OrbeloDMGrimMATalbottRERossEDImpaired comprehension of affective prosody in elderly subjects is not predicted by age-related hearing loss or age-related cognitive declineJ Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol200518253215681625

- KissIEnnisTAge-related decline in perception of prosodic affectAppl Neuropsychol2001825125411989730

- AllenRBrosgoleLFacial and auditory affect recognition in senile geriatrics, the normal elderly and young adultsInt J Neurosci19936833428063512

- CohenESBrosgoleLVisual and auditory affect recognition in senile and normal elderly personsInt J Neurosci198843891013215737

- TompkinsCAFlowersCRPerception of emotional intonation by brain-damaged adults: the influence of task processing levelsJ Speech Hear Res1985285275384087888

- RuffmanTHenryJDLivingstoneVPhillipsLHA meta-analytic review of emotion recognition and aging: implications for neuropsychological models of agingNeurosci Biobehav Rev20083286388118276008

- MitchellRLKingstonRABarbosa BouçasSLThe specificity of age-related decline in interpretation of emotion cues from prosodyPsychol Aging20112640641421401265

- SrinivasanRJMassaroDWPerceiving prosody from the face and voice: distinguishing statements from echoic questions in EnglishLang Speech20034612214529109

- RussellRLSocial communication impairments: pragmaticsPediatr Clin North Am200754483506 vi17543906

- AmodioDMFrithCDMeeting of minds: the medial frontal cortex and social cognitionNat Rev Neurosci2006726827716552413

- MakiYYamaguchiTKoedaTYamaguchiHCommunicative competence in Alzheimer’s disease: metaphor and sarcasm comprehensionAm J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen201328697423221027

- AmanzioMGeminianiGLeottaDCappaSMetaphor comprehension in Alzheimer’s disease: novelty mattersBrain Lang200810711017897706

- MashalNGavrieliRKavéGAge-related changes in the appreciation of novel metaphoric semantic relationsNeuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn20111852754321819177

- SzuchmanLTErberJTYoung and older adults’ metaphor interpretation: the judgments of professionals and nonprofessionalsExp Aging Res19901667722265668

- NewsomeMRGlucksbergSOlder adults filter irrelevant information during metaphor comprehensionExp Aging Res20022825326712079577

- GregoryMEWaggonerJEFactors that influence metaphor comprehension skills in adulthoodExp Aging Res19962283988665989

- MorroneIDeclercqCNovellaJLBescheCAging and inhibition processes: the case of metaphor treatmentPsychol Aging20102569770120853972

- TombaughTNHubleyAMThe 60-item Boston Naming Test: norms for cognitively intact adults aged 25 to 88 yearsJ Clin Exp Neuropsychol1997199229329524887

- ChenTBLinCYLinKNCulture qualitatively but not quantitatively influences performance in the Boston naming test in a Chinese-speaking populationDement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra20144869424847347

- MiottoECSatoJLuciaMCCamargoCHScaffMDevelopment of an adapted version of the Boston Naming Test for Portuguese speakersRev Bras Psiquiatr20103227928220428731

- McGinnisDText comprehension products and processes in young, young-old, and old-old adultsJ Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci20096420221119286643

- WrightHHCapiloutoGJSrinivasanCFergadiotisGStory processing ability in cognitively healthy younger and older adultsJ Speech Lang Hear Res20115490091721106701

- CannizzaroMSCoelhoCAAnalysis of narrative discourse structure as an ecologically relevant measure of executive function in adultsJ Psycholinguist Res20134252754923192423

- MotesMABiswalBBRypmaBAge-dependent relationships between prefrontal cortex activation and processing efficiencyCogn Neurosci2011211022792129

- TisserandDJJollesJOn the involvement of prefrontal networks in cognitive ageingCortex2003391107112814584569

- ArdilaARosselliMSpontaneous language production and aging: sex and educational effectsInt J Neurosci19968771788913820

- ChaseHWClarkLSahakianBJBullmoreETRobbinsTWDissociable roles of prefrontal subregions in self-ordered working memory performanceNeuropsychologia2008462650266118556028

- de RoverMPirontiVAMcCabeJAHippocampal dysfunction in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a functional neuroimaging study of a visuospatial paired associates learning taskNeuropsychologia2011492060207021477602

- SpinelliSPennanenLDettlingACFeldonJHigginsGAPryceCRPerformance of the marmoset monkey on computerized tasks of attention and working memoryBrain Res Cogn Brain Res20041912313715019709

- RodriguezJSZurcherNRBartlettTQNathanielszPWNijlandMJCANTAB delayed matching to sample task performance in juvenile baboonsJ Neurosci Methods201119625826321276821

- ZürcherNRRodriguezJSJenkinsSLPerformance of juvenile baboons on neuropsychological tests assessing associative learning, motivation and attentionJ Neurosci Methods201018821922520170676

- SimpsonEEMaylorEARaeGCognitive function in healthy older European adults: the ZENITH studyEur J Clin Nutr200559suppl 2S26S3016254577

- LeeAArcherJWongCKChenSHQiuAAge-related decline in associative learning in healthy Chinese adultsPLoS One20138e8064824265834

- McPheeJSHogrelJYMaierABPhysiological and functional evaluation of healthy young and older men and women: design of the European MyoAge studyBiogerontology20131432533723722256

- SalthouseTAAging and measures of processing speedBiol Psychol200054355411035219

- IversonGLBrooksBLAshtonVLJohnsonLGGualtieriCTDoes familiarity with computers affect computerized neuropsychological test performance?J Clin Exp Neuropsychol20093159460418972312

- StevesCJJacksonSHSpectorTDCognitive change in older women using a computerised battery: a longitudinal quantitative genetic twin studyBehav Genet20134346847923990175