Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association between physical activity (eg, energy expenditure) and survival over 11 years of follow-up in a large representative community sample of older Brazilian adults with a low level of education. Furthermore, we assessed sex as a potential effect modifier of this association.

Materials and methods

A population-based prospective cohort study was conducted on all the ≥60-year-old residents in Bambuí city (Brazil). A total of 1,606 subjects (92.2% of the population) enrolled, and 1,378 (85.8%) were included in this study. Type, frequency, and duration of physical activity were assessed in the baseline survey questionnaire, and the metabolic equivalent task tertiles were estimated. The follow-up time was 11 years (1997–2007), and the end point was mortality. Deaths were reported by next of kin during the annual follow-up interview and ascertained through the Brazilian System of Information on Mortality, Brazilian Ministry of Health. Hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals [CIs]) were estimated by Cox proportional-hazard models, and potential confounders were considered.

Results

A statistically significant interaction (P<0.03) was found between sex and energy expenditure. Among older men, increases in levels of physical activity were associated with reduced mortality risk. The hazard ratios were 0.59 (95% CI 0.43–0.81) and 0.47 (95% CI 0.34–0.66) for the second and third tertiles, respectively. Among older women, there was no significant association between physical activity and mortality.

Conclusion

It was possible to observe the effect of physical activity in reducing mortality risk, and there was a significant interaction between sex and energy expenditure, which should be considered in the analysis of this association in different populations.

Keywords:

Introduction

The quickly aging population and consequent increases of noncommunicable chronic diseases make physical inactivity a major risk factor among older adults. Worldwide figures show that physical inactivity is responsible for 6% of cardiovascular diseases, 7% of type II diabetes mellitus, 10% of breast cancers, and 10% of bowel cancers, which all contribute to 9% of premature deaths.Citation1 Global strategies by the World Health Organization to promote increases in levels of physical activityCitation2 have been incorporated into the Strategic Action Plan to Combat Noncommunicable Diseases in Brazil.Citation3 Evidence shows that the practice of regular physical activity could reduce the physiological process of aging and increase the survival rate by limiting both the development and progress of chronic diseases and by preserving physical functioning, in addition to psychological and cognitive benefits.Citation4

Some studies have already investigated the association between physical activity and mortality risk among older adults.Citation5,Citation6 However, this association was not consistent in different populations, and it showed sex differences. Despite research showing associations of similar magnitude among men and women,Citation6–Citation8 other studies have shown a reduction in the mortality risk only in older women,Citation9,Citation10 whereas other studies have found a significant association only in men.Citation11,Citation12 Therefore, sex could be a potential effect modifier of this association in older adults.

The prevalence of sedentary behavior increases with age,Citation13–Citation15 and health policies to promote physical activity among older adults are needed. In Brazil, information from the VIGITEL (Telephone-Based Surveillance of Risk and Protective Factors for Chronic Diseases), using a representative sample of adults from 26 state capitals and the Federal District, showed that 32.3% of older adults (aged 65 years and older) were physically inactive considering the following domains: leisure, work, transportation, and household.Citation14 Additional studies conducted in older Brazilian adults found that the prevalence of sedentary behavior related to leisure varied from 71% to 78%.Citation16,Citation17 After all physical activity domains were analyzed, the variation was even greater (26%–69%).Citation13,Citation18,Citation19 Previous findings from the baseline of the Bambuí cohort indicated that the sedentary behavior, considering all physical activities, was approximately 31.2%, and was higher in women (34.4%) than men (26.4%).Citation15

In regard to the effect of physical activity on mortality risk in older adults, it is important to consider that most evidence results from studies conducted in developed countries. There is no similar study that has been conducted in Latin America. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the association between energy expenditure, which is an estimate of physical activity level, and survival over 11 years of follow-up in a large representative community sample of older Brazilian adults with a low level of education. Furthermore, we aimed to assess sex as a potential effect modifier of this association.

Materials and methods

Data

Data were collected from the baseline interview (1997) of the Bambuí Cohort Study of Aging, which comprised 1,606 (92% of the total population) people aged 60 years and older in Bambuí (approximately 15,000 inhabitants), Minas Gerais State, southeastern Brazil. This cohort study was designed and developed to investigate the incidence and predictors of adverse health outcomes in an elderly Brazilian population with low education and income levels and in epidemiological transition (that is, with a high prevalence of noncommunicable chronic diseases, but also widespread Trypanosoma cruzi infection, a protozoan that causes Chagas disease, whose main feature is heart involvement). The Bambuí cohort members had a face-to-face interview each year, and there was an additional health examination at baseline and in selected years of follow-up. The Bambuí cohort methodology has been described elsewhere.Citation20 The Bambuí cohort study was approved by the ethics board of the Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Participants gave full informed consent to participate in this study and authorized death-certificate verification.

Mortality data source

Deaths that occurred from January 1, 1997 to December 31, 2007 were included in this analysis. Deaths were reported by next of kin during the annual follow-up interview and ascertained through the Brazilian System of Information on Mortality, Ministry of Health; death certificates were obtained for 98.9% of individuals. Deaths assigned to any cause were considered in this analysis.

Physical activity assessment

Information regarding physical activity was collected at baseline using a questionnaire with 23 closed questions and two open questions about physical activities performed by the participants in the past 3 months. The questionnaire included type, frequency, and average duration (in minutes) for each physical activity. The following physical activities were included: walking leisurely (2.5 mph [4 km/h]), going up stairs at a normal speed, going up stairs fast or carrying a load, mopping or scrubbing floors, cleaning windows, swimming (leisurely), dancing, rhythmic dancing, cycling (<10 mph, for leisure or to work), home repairs (painting), volleyball, tennis, basketball, football, walking fast (3.5 mph, brisk level, on a firm surface, walking for exercise), aerobics/gym workout, running/jogging, gardening (digging with a spade), sawing wood, horse riding (racing, galloping, trotting), shuttlecock (volleyball), cycling quickly, and cycling a steep hill. The physical activity data were carefully coded by a qualified physiotherapist, who is an author of this manuscript.

The level of physical activity was calculated based on the level of oxygen consumed for each physical activity. This method allowed the research team to quantify the energy expenditure in MET (metabolic equivalent task) according to the Compendium of Physical Activity.Citation21 One MET represents the energy expenditure by a resting individual with an oxygen consumption of 3.5 mL/kg of body weight per minute (3.5 mL·O2·kg−1·min−1). Therefore, the intensity of the physical activities was classified into three groups (light, moderate, and vigorous) according to the MET values.Citation22

The assessment of energy expenditure was calculated by multiplying the MET (intensity of the physical activity performed) by time (duration in minutes) and by frequency (how many times a week), considering only moderate and vigorous activities and a duration of 10 minutes or longer.Citation22,Citation23 The outcome variable of this study was the energy expenditure measured in MET-minute/week. In this study, tertiles of the MET variable at baseline were used. Further details about the physical activity assessment used in the Bambuí cohort have been described elsewhere.Citation15

Confounders

The potential confounding variables were selected based on previous research on the association between physical activity and mortality risk.Citation6–Citation8 The confounders included sociodemographics (age, sex, and years of education), health behaviors (smoking, alcohol consumption, and body mass index [BMI], kg/m2), and health status measures: systolic blood pressure (mmHg), total cholesterol (mg/dL), fasting glucose (mg/dL), B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) (pg/dL), stroke, angina, infarct, and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

Current smokers were those who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime and were currently smoking. Alcohol consumption was measured by the amount of alcohol consumed in the past 12 months before the interview. BMI was calculated using the standard formula (kg/m2), and was used as a continuous variable. The plasma levels of BNP, which is an important predictor of mortality risk among older adults infected by T. cruzi,Citation24 were measured by an immunoassay using microparticles (MEIA/AxSYM; Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA). A medical history of infarct was assessed by a single question and a history of stroke,Citation25 and anginaCitation26 by standardized instruments. Cognitive function was evaluated by the MMSE.

The interviews were conducted at participants’ homes and answered by the older adult him/herself or by a proxy (4.8%) for those with a cognitive deficit or a very serious health condition. Blood pressure and anthropometric measures together with collection of blood samples were performed at the project’s health clinic, except if the participants were not able to leave their homes. For the blood samples, participants were asked to fast for at least 12 hours. All research procedures were conducted by trained interviewers and well-qualified technicians. Further details can be found elsewhere.Citation20

Statistical analysis

The univariate analyses of the variables associated with energy expenditure at baseline were based on Pearson’s χ2 test and analysis of variance with multiple Bonferroni comparisons. The mortality rates were calculated using person-years at risk (pyrs) as the denominator for each sex and tertile of energy expenditure.

Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between energy expenditure and all-cause mortality risk during the 11-year follow-up period were estimated by Cox proportional-hazard models, after confirming that the assumption of proportionality among the hazards was met based on Schoenfeld residuals.

Three models were built in this analysis with progressive inclusion of confounders. The first model included tertiles of energy expenditure, age, sex, and years of education. At this stage, there was a significant interaction (P<0.02) between sex and energy expenditure, and the results are presented for each sex. It was decided to keep the interaction term in the following models. There was no significant interaction between physical activity and age (P>0.30). Smoking, alcohol consumption, and BMI were included in the second model. In the final model, the variables related to health status were added.

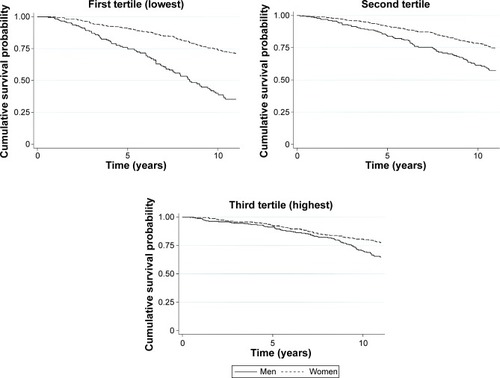

Survival curves were computed to show the interaction between sex and energy expenditure in both sexes. These curves were stratified by the physical activity level (tertiles of energy expenditure), and adjusted for all potential confounding variables selected in this study. The continuous variables were centralized around their mean values, and the categorical variables were fixed in the reference category.

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted: 1) excluding deaths that occurred in the first 2 years of follow-up, assuming that this group could have already been seriously ill, which would compromise the participant’s ability to do any physical activity,Citation6,Citation9,Citation27 and 2) excluding those participants who reported having at least one chronic disease at baseline (stroke, angina, infarct, diabetes, and hypertension) that would compromise the participant’s ability to do any physical activity and increase mortality risk.Citation9 Statistical analyses were conducted using version 13.0 of Stata statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Of the 1,606 eligible participants at baseline, 1,378 (85.8%) had available data for all study variables that were included in the analyses. During an average period of 8.9 years, 498 participants died (36.1%), and 90 (6.5%) were lost (that is, their vital status could not be assessed), yielding 12,255 pyrs of observation. The lost participants were slightly younger (mean age 67.3 years, standard deviation [SD] 5.9) compared to those included in the analyses (mean age 68.9, SD 7.0) (P=0.025), and both groups had similar numbers of men and women (P=0.592).

shows the sample characteristics at baseline by tertiles of energy expenditure. The highest tertile of energy expenditure was younger, with fewer women and fewer older adults with a lower level of education. This group also consumed more alcohol in the last year, had a lower prevalence of stroke, had higher MMSE scores, and had lower plasma levels of BNP.

Table 1 Selected baseline characteristics of participants by physical activity level

The all-cause mortality rate was 40.6 per 1,000 pyrs, and it was higher in men (49.5 per 1,000 pyrs) compared to women (35.2 per 1,000 pyrs). The mortality rates decreased with increases in energy expenditure. This tendency was observed in both sexes ().

Table 2 Number of deaths and mortality rates over 11 years, by tertiles of energy expenditure at baseline

presents the HRs and 95% CIs for 11-year survival by each energy-expenditure tertile. In men, all models showed that an increase in physical activity was associated with reductions in mortality risk. The HRs for the fully adjusted model were 0.59 (95% CI 0.43–0.81) and 0.47 (95% CI 0.34–0.66) for the second and third tertiles, respectively. In women, there was no association between physical activity and mortality risk. In the final adjusted analysis, HRs were 0.99 (95% CI 0.75–1.31) and 0.86 (95% CI 0.62–1.19) for the second and third tertiles, respectively. A significant interaction (P<0.03) was found between sex and tertiles of energy expenditure in all three models, showing that the effect of physical activity on survival over 11 years differed by sex.

Table 3 Hazard ratio for 11-year mortality, by tertiles of energy expenditure at baseline

Fully adjusted survival curves for 11 years of follow-up by sex and energy-expenditure tertiles are shown in . Survival decreased with time and was higher among women than men in the first and second tertiles of energy expenditure. Sex differences in mortality were not observed among older adults in the highest level of physical activity.

Figure 1 Cumulative survival probability estimates, adjusted for all confounders, by sex and tertiles of energy expenditure.

Abbreviation: MET, metabolic equivalent task.

There was no significant interaction between energy expenditure and age, even after full adjustment (P>0.30). The sensitivity analysis showed that excluding deaths that occurred in the first 2 years of follow-up did not change the significance levels of the associations observed in the three models. However, the effect of physical activity on mortality was stronger after excluding participants who had at least one chronic disease (stroke, angina, infarct, diabetes, and hypertension) at baseline, with a significant association in men (HR 0.41, 95% CI 0.22–0.77 and HR 0.30, 95% CI 0.16–0.58 for the second and third tertiles, respectively). In women, however, this association was not significant (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.43–1.53 and HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.34–1.39 for the second and third tertiles, respectively).

Discussion

The findings in this study showed an important interaction between sex and energy expenditure due to physical activity on the survival of older Brazilian adults. Higher levels of physical activity were associated with a greater reduction of all-cause mortality risk in men. However, there were no significant associations among older women. It was also found that among the participants in the highest tertile of energy expenditure, the survival rates of men and women were similar. This finding indicates that higher physical activity levels in older men increase their survival rate to a similar rate observed in older women.

The literature on the relationship between physical activity and the reduction of mortality risk in older adults shows conflicting findings, both in terms of the existence of an associationCitation11,Citation12,Citation28 and its strength.Citation9,Citation10,Citation29 These differences highlight the importance of investigating sex as a potential effect modifier of the relationship between physical activity and all-cause mortality in older adults. Studies have found similar findings to the results from the Bambuí cohort, which show a protective effect of physical activity only in older men.Citation11,Citation12 However, a German study showed a significant association only in women.Citation28

According to our knowledge, few studies have investigated the interaction between sex and physical activity to predict the risk of mortality in older adults, highlighting the importance of exploring this interaction in various populations.Citation30 Only one study conducted in diabetic participants aged 35 years and older (with a mean age between 56.6 and 58.5 years across categories of physical activity) from ten European countries showed a significant interaction between physical activity and sex in relation to the risk of mortality,Citation31 whereas other studies have not shown a significant interaction.Citation6–Citation8,Citation12 It is important to note that the findings from the Framingham study were similar to those observed in Bambuí, which showed that physical activity did not affect the risk of mortality in women, despite a nonsignificant interaction.Citation12

Regarding the type of physical activity, some studies showed that both leisure physical activitiesCitation29,Citation30 and household activitiesCitation29,Citation32 contributed to a reduction in mortality risk in older adults. However, these findings were not replicated by additional studies. For example, a German study found that household activities were associated with mortality risk, but it failed to show a dose response,Citation33 whereas Scottish data showed that household activities did not reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in older adults.Citation34 A study using data from the US Health and Retirement Study found a reduction in mortality risk only in women who practiced leisure physical activity, but not in those who did household or work-related physical activities.Citation30 Among older Chinese adults, household activities had a protective effect in men, but not in women, in relation to all-cause mortality.Citation35 Overall, in Bambuí, walking was the most frequent type of physical activity (72.4%), and among women, household activities were also very common.Citation15 Therefore, it is very important to consider the type of physical activity as a potential explanation for the observed sex differences reported by various studies. The instrument used to assess physical activity in the present study did not allow us to perform separate analyses for each type of activity, which is a limitation of this research.

Sex appears to be a potential effect modifier of the association between physical activity and survival among older adults, and this interaction was also found in Bambuí. The differences in survival rates among men and women disappeared in the highest energy-expenditure group, indicating a significant reduction in mortality risk among men who practiced physical activities. Overall, the observed difference in mortality risk among men and women could be partially attributed to the uneven prevalence of risk factors related to socioeconomic conditions, social networks, health behaviors, and biomarkers.Citation36,Citation37 The findings in the present study highlight the importance of physical activity in maintaining the mortality-risk differences among men and women.

The association between physical activity and mortality could be interpreted as a result of reverse causation, because older adults who report lower levels of physical activity could be in this group because they also presented poorer general health status and therefore higher mortality risk.Citation38 However, sensitivity analyses conducted in this study did not alter the findings, suggesting that the observed effect could be attributed to the physical activity level.

A strength of this study is the fact that it was conducted in an older adult population from Bambuí, with a long follow-up period and a high response rate. Furthermore, the data collected at baseline were obtained by trained professionals using standard techniques with regular quality-control checks. The physical activity data were measured in detail, considering the main physical activities practiced in this local community, and allowed the researchers to calculate energy expenditure. A possible limitation could be that physical activity information was self-reported.Citation38 A study that objectively measured energy expenditure found a stronger association with mortality risk compared to self-reported physical activity measures.Citation39 Another limitation was measuring energy expenditure only at baseline (ie, not assessing physical activity over time). However, these potential limitations could have been partially attenuated by the strength of the associations found in the present study.Citation38

In conclusion, the findings in this study showed that sex is an important effect modifier in the association between energy expenditure and mortality risk among older Brazilian adults. This protective effect of physical activity was only found in men. This study was the first to investigate older adults in Latin America at the population level with a long follow-up period and a very low attrition rate. Finally, it was possible to observe the effect of physical activity on reducing mortality risk, and there was a significant interaction between sex and energy expenditure, which should be considered in the analysis of this association in various populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos (FINEP), Centro de Pesquisas René Rachou (CPqRR-Fiocruz Minas), and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), which funded this study. CCC, MFLC, JOAF, and SVP are research-productivity scholars of CNPq.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LeeIMShiromaEJLobeloFPuskaPBlairSNKatzmarzykPTEffect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancyLancet2012380983821922922818936

- World Health OrganizationGlobal Recommendations on Physical Activity for HealthGenevaWHO2010 Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/enAccessed July 11, 2014

- MaltaDCBarbosa da SilvaJPolicies to promote physical activity in BrazilLancet2012380983819519622818935

- American College of Sports MedicineChodzko-ZajkoWJProctorDNAmerican College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adultsMed Sci Sports Exerc20094171510153019516148

- WooJHoSCYuALLifestyle factors and health outcomes in elderly Hong Kong Chinese aged 70 years and overGerontology200248423424012053113

- Paganini-HillAKawasCHCorradaMMActivities and mortality in the elderly: the Leisure World Cohort StudyJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci201166555956721350247

- KhawKTJakesRBinghamSWork and leisure time physical activity assessed using a simple, pragmatic, validated questionnaire and incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and women: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk prospective population studyInt J Epidemiol20063541034104316709620

- LeitzmannMFParkYBlairAPhysical activity recommendations and decreased risk of mortalityArch Intern Med2007167222453246018071167

- BrownWJMcLaughlinDLeungJPhysical activity and all-cause mortality in older women and menBr J Sports Med201246966466822219216

- OttenbacherAJSnihSAKarmarkarARoutine physical activity and mortality in Mexican Americans aged 75 and olderJ Am Geriatr Soc20126061085109122647251

- HayasakaSShibataYIshikawaSPhysical activity and all-cause mortality in Japan: the Jichi Medical School (JMS) Cohort StudyJ Epidemiol2009191242719164869

- ShortreedSMPeetersAForbesABEstimating the effect of long-term physical activity on cardiovascular disease and mortality: evidence from the Framingham Heart StudyHeart201399964965423474622

- HallalPCVictoraCGWellsJCLimaRCPhysical inactivity: prevalence and associated variables in Brazilian adultsMed Sci Sports Exerc200335111894199014600556

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde Secretaria de Gestão Estratégica e ParticipativaVigitel Brasil 2011: Vigilância de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas por Inquérito TelefônicoBrasíliaMinistério da Saúde2012

- RamalhoJRLima-CostaMFFirmoJOPeixotoSVEnergy expenditure through physical activity in a population of community-dwelling Brazilian elderly: cross-sectional evidences from the Bambuí Cohort Study of AgingCad Saude Publica201127Suppl 3S399S40821952861

- ZaituneMPBarrosMBCésarCLCarandinaLGoldbaumMVariables associated with sedentary leisure time in the elderly in Campinas, São Paulo State, BrazilCad Saude Publica200723613291338 Portuguese17546324

- PitangaFJLessaIPrevalence and variables associated with leisure-time sedentary lifestyle in adultsCad Saude Publica2005213870877 Portuguese15868045

- SiqueiraFVFacchiniLAPicciniRXPhysical activity in young adults and the elderly in areas covered by primary health care units in municipalities in the south and northeast of BrazilCad Saude Publica20082413954 Portuguese18209833

- ZaituneMPBarrosMBCésarCLCarandinaLGoldbaumMAlvesMCFactors associated with global and leisure-time physical activity in the elderly: a health survey in São Paulo (ISA-SP), BrazilCad Saude Publica201026816061618 Portuguese21229219

- Lima-CostaMFFirmoJOUchoaECohort profile: the Bambuí (Brazil) Cohort Study of AgeingInt J Epidemiol201140486286720805109

- AinsworthBEHerrmannSDMeckesN2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET valuesMed Sci Sports Exerc20114381575158121681120

- United States Department of Health and Human ServicesPhysical activity guidelines2008 Available from: www.health.gov/paguidelinesAccessed January 15, 2010

- HaskellWLLeeIMPateRRPhysical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart AssociationMed Sci Sports Exerc20073981423143417762377

- Lima-CostaMFCesarCCPeixotoSVRibeiroALPlasma B-type natriuretic peptide as a predictor of mortality in community-dwelling older adults with Chagas disease: 10-year follow-up of the Bambuí Cohort Study of AgingAm J Epidemiol2010172219019620581155

- No authors listedPlan and operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Series 1: programs and collection proceduresVital Health Stat 11994321407

- RoseGThe diagnosis of ischaemic heart pain and intermittent claudication in field surveysBull World Health Organ19622764565813974778

- UeshimaKIshikawa-TakataKYorifujiTPhysical activity and mortality risk in the Japanese elderly: a cohort studyAm J Prev Med201038441041820307810

- BuckschJPhysical activity of moderate intensity in leisure time and the risk of all-cause mortalityBr J Sports Med200539963263816118301

- ChenLJFoxKRKuPWSunWJChouPProspective associations between household-, work-, and leisure-based physical activity and all-cause mortality among older Taiwanese adultsAsia Pac J Public Health201224579580522426557

- WenCPWaiJPTsaiMKMinimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: a prospective cohort studyLancet201137897981244125321846575

- SluikDBuijsseBMuckelbauerRPhysical activity and mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus: a prospective study and meta-analysisArch Intern Med2012172171285129522868663

- ParkSLeeJKangDYRheeCWParkBJIndoor physical activity reduces all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality among elderly womenJ Prev Med Public Health2012451212822389755

- AutenriethCSBaumertJBaumeisterSEAssociation between domains of physical activity and all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortalityEur J Epidemiol2011262919921153912

- StamatakisEHamerMLawlorDAPhysical activity, mortality, and cardiovascular disease: is domestic physical activity beneficial? The Scottish Health Survey – 1995, 1998, and 2003Am J Epidemiol2009169101191120019329529

- YuRLeungJWooJHousework reduces all-cause and cancer mortality in Chinese menPLoS One201385e61529 Erratum in: PLoS One. 2013:8(11)23667441

- WingardDLThe sex differential in mortality rates: demographic and behavioral factorsAm J Epidemiol198211522052167058779

- RogersRGEverettBGOngeJMKruegerPMSocial, behavioral, and biological factors, and sex differences in mortalityDemography201047355557820879677

- SamitzGEggerMZwahlenMDomains of physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studiesInt J Epidemiol20114051382140022039197

- ManiniTMEverhartJEPatelKVDaily activity energy expenditure and mortality among older adultsJAMA2006296217117916835422