Abstract

Purpose

It is a known fact that age is a strong predictor of adverse events in acute coronary syndrome (ACS). In this context, the main risk factor in elderly patients, ie, frailty syndrome, gains special importance. The availability of tools to identify frail people is relevant for both research and clinical purposes. The purpose of this study was to investigate the correlation of a scale for assessing frailty – the Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI) and its domains (mental and physical) – with other research tools commonly used for comprehensive geriatric assessment in patients with ACS.

Patients and methods

The study covered 135 people and was carried out in the cardiology ward at T Marciniak Lower Silesian Specialist Hospital in Wroclaw, Poland. The patients were admitted with ACS. ST segment elevation myocardial infarction and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction were defined by the presence of certain conditions in reference to the literature. The Polish adaptation of the TFI was used for the frailty syndrome assessment, which was compared to other single measures used in geriatric assessment: the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (ADLs).

Results

The mean TFI value in the studied group amounted to 7.13±2.81 (median: 7, interquartile range: 5–9, range [0, 14]). Significant correlations were demonstrated between the values of the TFI and other scales: positive for HADS (r=0.602, P<0.001) and the reverse for MMSE (r=−0.603, P<0.001) and IADL (r=−0.462, P<0.001). Patients with a TFI score ≥5 revealed considerably higher values on HADS (P<0.001) and considerably lower values on the MMSE (P<0.001) and IADL scales (P=0.001).

Conclusion

The results for the TFI comply with the results of other scales (MMSE, HADS, ADL, IADL), which confirm the credibility of the Polish adaptation of the tool. Stronger correlations were observed for mental components and the mental scales turned out to be independently related to the TFI in a multidimensional analysis.

Introduction

Extension of life expectancy is related to a significant increase in the number of elderly people.Citation1 It results in an increased demand for medical services and entails the need to improve quality of life and everyday functioning of the eldest citizens.Citation2 With regard to the above, the main risk of complications in elderly people, ie, frailty syndrome (FS), gains special importance.Citation2–Citation4

It is considered that patients with FS require special attention. On the one hand, the risk of their disability or death is quite high, but, on the other hand, many elements of FS can be reversed if diagnosed appropriately. Prevention might be most beneficial for those at high risk for dependency and disability, ie, frail older people.Citation3

Recently, the literature has emphasized the contribution of FS to acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Half of cases of ACS concern patients ≥75 years old.Citation5 It is known that age is a strong predictor of adverse events in ACS.Citation6 The elderly population is more susceptible to hemorrhagic complications, renal failure, and incidents involving the central nervous system. Nevertheless, patients at increased risk may benefit significantly from coronary interventions. Research shows, however, that invasive therapy and cardiological treatment are rarely used in this population, and the population is also rarely qualified for clinical studies.Citation7 Not only age but also related disease conditions (anemia, renal insufficiency, FS, disturbed cognitive functions) are the cause of adverse events after ACS. The American Heart Association Council recommends taking FS, cognitive functions, and concomitant diseases into account while making risk assessments and selecting therapy in ACS. There is evidence that the changes influence prognosis after ACS and are of key importance for selecting therapy in patients with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).Citation5

The availability of tools to identify frail people is relevant to both research and clinical purposes. In order to avoid costs and unnecessary assessments, valid and low-cost tools are needed to screen elderly people who are at particular risk of developing adverse outcomes.Citation8 With regard to disability prevention, valid screening instruments are needed to identify frail older people.

With regard to the above, early diagnosis of FS and implementation of appropriate intervention aimed at minimizing the negative effects of the syndrome and improving the quality of life of patients suffering from the disease are extremely important.Citation9 However, in practice, this means facing various problems related to the previously mentioned lack of coherent definition of FS or uniform diagnostic criteria for the syndrome. The clinical markers of frailty include: nutritional condition, mobility, activity, strength and endurance, cognitive functions, and mood. Nevertheless, the large number and variability of the factors determining the presence of FS justifies the creation of a simple screening tool that could be used for diagnosing the syndrome. Recent years have seen the development of various tools meeting the criteria; their value varies, though, due to the fact that none of them allows a simultaneous analysis of all the components of FS.

The Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI), a tool proposed by Gobbens et alCitation10 is based on the concept of the frailty model.Citation11 The tool is simple for a patient and characterized good psychometric properties when studied in a Polish population.Citation12

Functional status refers to the ability to perform activities necessary or desirable in daily life. Disability is a well-known major adverse outcome of physical frailty.Citation13,Citation14 Therefore, we measured the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (ADLs),Citation15 which include bathing, dressing, toileting, maintaining continence, grooming, feeding, transport, and the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) Scale. IADLs refer to the ability to maintain an independent household, including shopping for groceries, driving or using public transportation, using the telephone, performing housework, doing home repair, preparing meals, doing laundry, taking medication, and handling finances.Citation16

Anxiety and depression are common in older people, and also may predispose them to frailty. Previous studies have reported on cross-sectional association and poor cognition, and it has been suggested that frailty might be an indicator of future cognitive impairment. Cognitive impairment is an independent marker of functional decline and mortality. Cognitive impairment is also responsible for loss of independence, affecting individuals and families and having an impact on the health care system. Some researchers have suggested that cognitive function is a predictor of becoming frail.Citation17–Citation20

The latest definitions of FS adopt a multidimensional concept, where FS is described as a dynamic condition depending on a number of factors, including physical, mental, and social ones, that interact and distort the physiological balance.Citation21–Citation23 Therefore, the researchers need to select the appropriate definition as well as tools to study FS.Citation24

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the correlation of the FS test scale – the TFI and its domains (mental and physical) – with other research tools, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), ADL, IADL, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), commonly used for comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) in patients with ACS.

Methods

Study population

The study covered 135 people, including 53 (39.3%) women and 82 (60.7%) men. The study was carried out in the cardiology ward at T Marciniak Lower Silesian Specialist Hospital in Wroclaw, Poland. Data was collected from January 2014 to August 2014. Patients were admitted with ACS. ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) was defined as the presence of: 1) typical chest pain lasting >30 minutes; 2) ST segment elevation ≥2 mm in contiguous chest leads and/or ST segment elevation at ≥1 mm in ≥2 standard leads, or new left bundle branch block; and 3) positive cardiac necrosis markers. NSTEMI was defined as the presence of: 1) typical chest pain; 2) absence of ST segment elevation; and 3) positive cardiac necrosis markers. Only the patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were included in the analysis. Inclusion criteria were age ≥65 years and written informed consent for participation in the study. The assessment was made in hemodynamically stable patients. Patients admitted with severe disturbances, such as cardiogenic shock or pulmonary edema, and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, cancer, and mental disorders, as well as patients addicted to alcohol and other psychoactive substances, were excluded from the study.

This study was approved by the Bioethical Commission of the Medical University of Wroclaw (number KB-521/2014).

Measures

Description of the TFI

The TFI consists of two different parts. One part addresses the sociodemographic characteristics of a participant (sex, age, marital status, country of origin, educational level, and monthly income) and potential determinants of frailty. The second part addresses the components of frailty. Part two of the TFI comprises 15 self-reported questions, divided into three domains. The physical domain (0–8 points) consists of eight questions related to physical health, unexplained weight loss, difficulty in walking, balance problems, hearing problems, vision problems, strength in hands, and physical tiredness. The psychological domain (0–4 points) comprises four items related to cognition, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and coping. The social domain (0–3 points) comprises three questions related to living alone, social relations, and social support. Eleven items from part two of the TFI have two response categories (“yes” and “no”), while the other items have three (“yes”, “no,” and “sometimes”). “Yes” or “sometimes” responses are scored 1 point each, while “no” responses are scored 0. The instrument’s total score may range from 0 to 15: the higher the score, the higher one’s frailty. Frailty is diagnosed when the total TFI score is >5.Citation10–Citation12

Description of the MMSE

The MMSE is a very brief, easily administered mental status examination that has proved to be a highly reliable and valid instrument for detecting and tracking the progression of the cognitive impairment associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Consequently, the MMSE is the most widely used mental status examination in the world.Citation25,Citation26 The maximum MMSE score is 30. The cut-off scores of 24–25 provide a reliable diagnosis of dementia with high sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic values.Citation25,Citation26

Description of the HADS

The HADS is a screening tool for anxiety and depression in nonpsychiatric clinical populations. It is thought to tap into the construct of affect. The scale consists of 14 items (seven each for anxiety and depression). Responses are based on the relative frequency of symptoms over the preceding week. Possible scores range from 0 to 21 for each subscale. An analysis of scores on the two subscales supported the differentiation of each mood state into four ranges: “mild cases” (scores 8–10), “moderate cases” (scores 11–15), and “severe cases” (scores 16 or higher).Citation27,Citation28

Description of the ADLs

The index of ADLs counts the number of ADLs for which a person needs help, and is the classic measure of the severity of the need for personal assistance services and other long-term services and support. Clients are scored with yes/no for independence in each of the six functions. A score of 6 indicates full function; 4 indicates moderate impairment; and 2 or less indicates severe functional impairment.Citation14

Description of IADLs

This index measures a patient’s ability to maintain an independent household, eg, shopping for groceries, driving or using public transportation, using the telephone, performing housework, doing home repair, preparing meals, doing laundry, taking medication, and handling finances.Citation16

Analytic strategy

Correct distribution of the continuous variables was verified with the Shapiro–Wilk test, and their statistical characteristics are presented as arithmetic means, standard deviations, medians, interquartile range (IQRs), and ranges. The power and direction of the relationship between the values of the TFI and other scales were evaluated based on the value of the Pearson’s coefficient of linear correlation (r). The Student’s t-test was used for nonrelated variables to compare the results of each scale in the subgroups of patients with TFI ≥5 and <5. The compliance of distribution of each scale value was evaluated based on the value of coefficient Φ and the result of Pearson’s chi-square test. The calculations were made with the use of Statistica 10 software (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA); the assumed level of significance was P≤0.05 for all tests.

Results

The study covered a group of 135 people, including 53 (39.3%) women and 82 (60.7%) men. The mean age of the studied population was 69.8±11.4 years (median: 68, IQR: 60–79, range: 50–92). The sociodemographic data are given in .

Table 1 Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the studied population

Values of TFI

The mean value of the TFI in the studied group amounted to 7.13±2.81 (median: 7, IQR: 5–9, range: 0–14). The studied population included 105 (77.8%) people with a value of TFI ≥5 and 30 (22.2%) non-frail people with a TFI value <5.

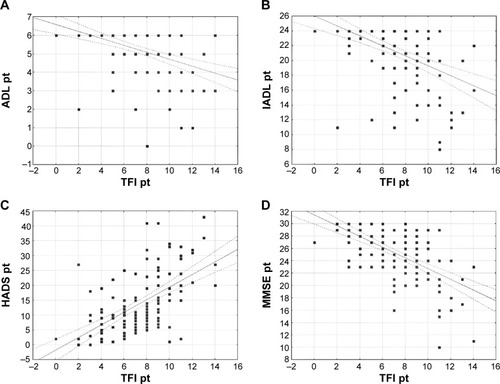

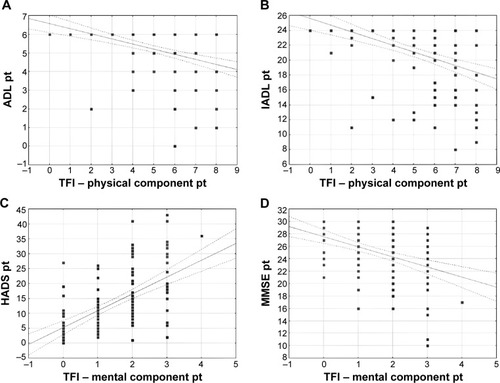

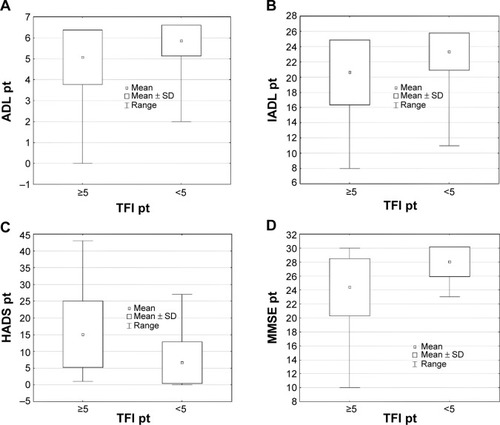

Relationship between the TFI and values of the ADL scale

The mean value of the ADL scale in the studied group amounted to 5.24±1.24 (median: 6, IQR: 5–6, range: 0–6). The studied population included 25 (18.5%) people with values of the ADL scale <5 and 110 (81.5%) with values of the ADL scale ≥5. Significant reverse correlation between the values of the ADL scale and the values of the TFI (r=−0.428, P<0.001) () and its physical dimension (r=−0.461, P<0.001) () were demonstrated. Patients with a TFI ≥5 demonstrated considerably lower values of the ADL scale (P=0.002) (). A significant relationship between the coexistence of the value of the TFI ≥5 and the value of the ADL scale <5 (Φ=0.209, P=0.015) () was demonstrated.

Figure 1 Relationships between the TFI values and values of the ADL (A), IADL (B), HADS (C), and MMSE (D) scales.

Abbreviations: ADL, Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IADL, The Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; TFI, Tilburg Frailty Indicator.

Figure 2 Relationships between the values of the physical dimension of the TFI and the values of the ADL (A) and IADL (B) scales, and between the values of the mental dimension of the TFI and the values of the HADS (C) and MMSE (D) scales.

Abbreviations: ADL, Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IADL, The Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; TFI, Tilburg Frailty Indicator.

Figure 3 Statistical characteristics of the values of the ADL (A), IADL (B), HADS (C), and MMSE (D) scales in the subgroups of patients with the TFI values ≥5 and <5.

Relationship of the TFI with the values of the IADL scale

The mean value of the IADL scale in the studied population amounted to 21.21±4.08 (median: 24, IQR: 20–24, range: 8–24). The studied population included only five (3.7%) people with the value of the IADL scale <12 and as many as 130 (96.3%) people with the IADL scale value ≥12. Significant reverse correlations between the values of the IADL scale and the TFI (r=−0.462, P<0.001) () and its physical dimension (r=−0.462, P<0.001) () were demonstrated. Patients with a TFI ≥5 revealed considerably lower values of the IADL scale (P=0.001) (). However, no significant relationship between the coexistence of the TFI value ≥5 and the value of the IADL scale <12 (Φ=0.010, P=0.903) () was discovered.

Relationship of the TFI with the values of the HADS

The mean value of the HADS in the studied group amounted to 13.25±9.89 (median: 10, IQR: 23–29, range: 0–43). The studied population included 91 (67.4%) people with a value of the HADS >7 and 44 (32.6%) people with a value of the HADS ≤7. Significant positive correlations between the values of the HADS and the value of the TFI (r=0.602, P<0.001) () and its mental dimensions (r=0.586, P<0.001) () were demonstrated. Patients with a TFI ≥5 revealed considerably higher values of the HADS (P<0.001) (). A significant relationship between the coexistence of the value of the TFI ≥5 and the value of the HADS >7 (Φ=0.389, P=0.001) () was also demonstrated.

Relationship of the TFI with the values of the MMSE scale

The mean value of the MMSE scale in the studied group amounted to 25.22±4.05 (median: 26, IQR: 23–29, range: 10–30). The studied population included 40 (29.6%) people with the value of the MMSE scale <24 and 95 (70.4%) people with the value of the MMSE scale ≥24. Significant reverse correlations between the values of the MMSE scale and the value of the TFI (r=−0.603, P<0.001) () and its mental dimension (r=−0.413, P<0.001) () were demonstrated. Patients with the TFI ≥5 revealed considerably lower values of the MMSE scale (P<0.001) (). A significant relationship between the coexistence of the value of the TFI ≥5 and the value of the MMSE scale <24 (Φ=0.269, P=0.002) () was also demonstrated.

Table 2 Distribution of the number and percentage of patients with different values of the ADL, HADS, and MMSE scales in the subgroups of patients with the TFI values ≥5 and <5

Multidimensional analysis

A multiple regression analysis revealed that the parameters with a significant, independent effect on the TFI level included the values of the HADS and MMSE scale. In turn, in the multidimensional model of logistic regression, the only independent predicator of the TFI ≥5 turned out to be the occurrence of the HADS value >7 (odds ratio [OR] =4.84, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.91–12.22, P=0.001). No statistically significant relationship between the coexistence of a TFI ≥5 and a value of the ADL scale <5 (OR =3.74, 95% CI: 0.42–33.42, P=0.234) and MMSE scale <24 (OR =3.57, 95% CI: 0.72–17.66, P=0.116) was demonstrated.

Discussion

Neither a unanimous operating definition of FS nor uniform diagnostic criteria of the syndrome have been developed so far.Citation31 FS is a consequence of reduced physiological reserves of many body organs.Citation29–Citation31 Moreover, FS results in poorer functioning in biopsychosocial areas, translating into a poorer response to both physical and mental stressors. Factors involved in the etiopathogenesis of FS include biological (inflammatory, hormones), clinical (sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and other concomitant diseases), and social (social isolation, poor financial condition).Citation32 The occurrence of FS leads to poorer functioning in the elderly in many aspects, as well as to an increased risk of disease, hospitalization, institutionalization, or even death; the problems gain particular significance in the case of patients suffering from chronic diseases.Citation8

There are a number of instruments (clinical and instrumental tests, self-return questionnaires, etc) that allow the assessment of the components of FS from the physical domain (physical activity, nutrition, handgrip strength, risk of falling down)Citation15,Citation16,Citation29,Citation31,Citation32 mental domain (cognitive functions, mood, depression)Citation25,Citation26,Citation29,Citation30 and social domain (social isolation, social support).Citation10,Citation11 Furthermore, the literature mentions research tools that can be used for comprehensive diagnostics of FS: 1) the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Scale; 2) the Edmonton Frail Scale (EFS); 3) the TFI; 4) the Canadian Study on Health and Aging (CSHA) Frailty Index; 5) the FRAIL scale; and 6) the Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI).Citation8,Citation11,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33

The purpose of the present study was to establish whether the TFI correlates with single tools (ADL, IADL, MMSE, and HADS) used for assessing various aspects of elderly age in CGA, and to compare the predictive values of single-measure instruments with the TFI in the ACS population. A similar study was performed by Gobbens et alCitation34 where the authors assessed the predictive validity of the eight individual self-reported components of the physical frailty subscale of the TFI for the total disability, ADL disability, and IADL disability in older people. Low physical activity was associated with a greater total and ADL disability. Slowness was associated with a higher total and IADL disability, and weakness with a lower IADL disability.Citation34 In our study, a significant relationship between the coexistence of a TFI value ≥5 and an ADL scale value <5 was demonstrated, which means, similarly to Gobbens and van Assen’s research, that physical frailty measured by the TFI is comparable with lower ADL scores.Citation34 The same relationship was observed between the coexistence of a TFI value ≥5 and the HADS and MMSE scale values. Additionally, significant positive correlations between the HADS values had significant positive correlations with the TFI and its mental dimension, were discovered. Patients with a TFI value ≥5 demonstrated significantly higher values of the HADS. Therefore, it can be concluded that frailty causes deterioration of the cognitive functions and contributes to the occurrence of fear and depression as measured in the mental dimension of the TFI scale. Cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in older individuals, and managing elderly patients with ACS can be challenging. The presence of FS in the elderly population can be meaningful for taking decisions as to therapy and for stratification of cardiovascular risk. The majority of scales used for risk assessment are based on chronological age. However, chronological age does not always reflect the biological age of the patient and its use may lead to inaccurate estimation of the patient’s risk. Nowadays, the significance of biological age for making medical decisions is emphasized. This can be identified using FS diagnostics, which are the exponents of advanced age. Therefore, the use of the TFI, which is a multidimensional tool, can be helpful for assessing frailty at the bedside with ACS patients, and may change our approach towards those patients because they may need special attention. As we said previously, recent study demonstrated that over 50% of elderly patients with cardiovascular diseases are frail, which makes FS a major problem as frailty is associated with increased mortality.Citation8

In the literature, we found only one study in which frailty was measured as an outcome in elderly patients with ACS. The study was performed by Graham et al and the authors administered the EFS to ACS patients to assess frailty. They concluded that the EFS may also be used as a simple frailty assessment tool administered by non-geriatricians to a group of older patients with ACS.Citation35

The TFI is not superior to other frailty instruments, but it might be a useful tool for assessing frailty and helping with the geriatric assessment.

Study limitations

We are well aware of potential limitations of this study. The most important of these stems from the fact that our study sample size was relatively low, and the sample was recruited at a single center.

Conclusion

The results of the TFI comply with the results of other scales (ADL, IADL, MMSE, and HADS), which confirms the credibility of the Polish adaptation of the tool. Stronger correlations concerned mental components, while the mental scales turned out to be independently related to TFI in a multidimensional analysis. To conclude, the assessment of frailty with TFI can be very useful for CGA.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- European Commission2009 Ageing Report: Economic and Budgetary Projections for the EU-27 Member States 2008–2060LuxembourgOffice for Official Publications of the European Communities2009 Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication14992_en.pdfAccessed October 21, 2012

- EkerstadNSwahnEJanzonMFrailty is independently associated with short-term outcomes for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctionCirculation20111242397240422064593

- HoganDBMacKnightCBergmanHSteering Committee, Canadian Initiative on Frailty and AgingModel, definitions, and criteria of frailtyAging Clin Exp Res20031512914580013

- ŻyczkowskaJGrądalskiTZespół słabości (frailty) – co powinien wiedzieć o nim onkolog? [Frailty – an overview for oncologists]Onkologia w Praktyce Klinicznej201067984 Polish

- AlexanderKPNewbyLKCannonCPAmerican Heart Association Council on Clinical CardiologySociety of Geriatric CardiologyAcute coronary care in the elderly, part I: non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: in collaboration with the Society of Geriatric CardiologyCirculation20071152549256917502590

- AvezumAMakdisseMSpencerFGRACE InvestigatorsImpact of age on management and outcome of acute coronary syndrome: observations from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE)Am Heart J2005149677315660036

- TopolEJCaliffRMVan de WerfFPerspectives on large-scale cardiovascular clinical trials for the new millennium. The Virtual Coordinating Center for Global Collaborative Cardiovascular Research (VIGOUR) GroupCirculation199795107210829054772

- AfilaloJFrailty in patients with cardiovascular disease: why, when, and how to measureCurr Cardiovasc Risk Rep2011546747221949560

- TopinkováEAging, disability and frailtyAnn Nutr Metab200852Suppl 161118382070

- GobbensRJvan AssenMALuijkxKGScholsJMThe predictive validity of the Tilburg Frailty Indicator: disability, health care utilization, and quality of life in a population at riskGerontologist20125261963122217462

- GobbensRJvan AssenMALuijkxKGWijnen-SponseleeMTScholsJMThe Tilburg Frailty Indicator: psychometric propertiesJ Am Med Dir Assoc20101134435520511102

- UchmanowiczIJankowska-PolańskaBŁoboz-RudnickaMManulikSŁoboz-GrudzieńKGobbensRJCross-cultural adaptation and reliability testing of the Tilburg Frailty Indicator for optimizing care of Polish patients with frailty syndromeClin Interv Aging20149997100125028543

- CesariMPenninxBWPahorMInflammatory markers and physical performance in older persons: the InCHIANTI studyJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci20045924224815031308

- American College of Sports MedicineChodzko-ZajkoWJProctorDNAmerican College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adultsMed Sci Sports Exerc2009411510153019516148

- KatzSFordABMoskowitzRWJacksonBAJaffeMWStudies of illness in the aged. The Index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial functionJAMA196318591491914044222

- Barberger-GateauPDartiguesJFLetenneurLFour Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Score as a predictor of one-year incident dementiaAge Ageing1993224574638310892

- Ní MhaoláinAMFanCWRomero-OrtunoRFrailty, depression, and anxiety in later lifeInt Psychogeriatr20122481265127422333477

- DodsonJAChaudhrySIGeriatric conditions in heart failureCurr Cardiovasc Risk Rep2012640441023997843

- LupónJGonzálezBSantaeugeniaSPrognostic implication of frailty and depressive symptoms in an outpatient population with heart failureRev Esp Cardiol200861835842 English, Spanish18684366

- WellsJLSeabrookJAStoleePBorrieMJKnoefelFState of the art in geriatric rehabilitation. Part I: review of frailty and comprehensive geriatric assessmentArch Phys Med Rehabil20038489089712808544

- WooJGogginsWShamAHoSCSocial determinants of frailtyGerontology200551640240816299422

- OstirGVOttenbacherKJMarkidesKSOnset of frailty in older adults and the protective role of positive affectPsychol Aging200419340240815382991

- GobbensRJLuijkxKGWijnen-SponseleeMTScholsJMIn search of an integral conceptual definition of frailty: opinions of expertsJ Am Med Dir Assoc201011533834320511101

- FisherALJust what defines frailty?J Am Geriatr Soc200553122229223016398915

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEFanjiangGMini-Mental State Examination: Clinical GuideOdessa, FLPsychological Assessment Resources2001

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res1975121891981202204

- ZigmondASSnaithRPThe hospital anxiety and depression scaleActa Psychiatr Scand1983673613706880820

- WoolrichRAKennedyPTasiemskiTA preliminary psychometric evaluation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in 963 people living with a spinal cord injuryPsychol Health Med200611809017129897

- AminzadehFDalzielWMolnarFJTargeting frail older adults for outpatient comprehensive geriatric assessment and management services: an overview of concepts and criteriaRev Clin Gerontol2002128292

- CampbellAJBuchnerDMUnstable disability and the fluctuations of frailtyAge Ageing1997263153189271296

- RockwoodKWhat would make a definition of frailty successful?Age Ageing20053443243416107450

- FerrucciLGuralnikJMStudenskiSFriedLPCutlerGBJrWalstonJDInterventions on Frailty Working GroupDesigning randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus reportJ Am Geriatr Soc20045262563415066083

- FriedLPTangenCMWalstonJCardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research GroupFrailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotypeJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200156M146M15611253156

- GobbensRJvan AssenMAThe Prediction of ADL and IADL Disability Using Six Physical Indicators of Frailty: A Longitudinal Study in the NetherlandsCurr Gerontol Geriatr Res2014201435813724782894

- GrahamMMGalbraithDPO’NeillDRolfsonDBDandoCNorrisCMFrailty and outcome in elderly patients with acute coronary syndromeCan J Cardiol2013291610161524183299