Abstract

There are many anatomical, physiopathological, and cognitive changes that occur in the elderly that affect different components of airway management: intubation, ventilation, oxygenation, and risk of aspiration. Anatomical changes occur in different areas of the airway from the oral cavity to the larynx. Common changes to the airway include tooth decay, oropharyngeal tumors, and significant decreases in neck range of motion. These changes may make intubation challenging by making it difficult to visualize the vocal cords and/or place the endotracheal tube. Also, some of these changes, including but not limited to, atrophy of the muscles around the lips and an edentulous mouth, affect bag mask ventilation due to a difficult face-mask seal. Physiopathologic changes may impact airway management as well. Common pulmonary issues in the elderly (eg, obstructive sleep apnea and COPD) increase the risk of an oxygen desaturation event, while gastrointestinal issues (eg, achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease) increase the risk of aspiration. Finally, cognitive changes (eg, dementia) not often seen as related to airway management may affect patient cooperation, especially if an awake intubation is required. Overall, degradation of the airway along with other physiopathologic and cognitive changes makes the elderly population more prone to complications related to airway management. When deciding which airway devices and techniques to use for intubation, the clinician should also consider the difficulty associated with ventilating the patient, the patient’s risk of oxygen desaturation, and/or aspiration. For patients who may be difficult to bag mask ventilate or who have a risk of aspiration, a specialized supralaryngeal device may be preferable over bag mask for ventilation. Patients with tumors or decreased neck range of motion may require a device with more finesse and maneuverability, such as a flexible fiberoptic broncho-scope. Overall, geriatric-focused airway management is necessary to decrease complications in this patient population.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Case 1

A frail, 87-year-old female with a body mass index (BMI) of 18.5 kg/m2 presented to the operating room with a left pelvic fracture for percutaneous fixation. Her preoperative airway exam showed normal airway indices with a Mallampati class I, oral aperture of 3 fingerbreadths, thyromental distance of 3 fingerbreadths, and full neck range of motion (ROM). She was expected to have a “normal” airway necessitating conventional management only with bag mask ventilation (BMV) and direct laryngoscopy following anesthetic induction with propofol and rocuronium. However, BMV proved to be difficult, requiring a chin lift maneuver and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) >20 cm of water; thus, risking insufflation of the stomach. Direct laryngoscopy with a Macintosh 3 blade required two attempts to visualize the vocal cords and one attempt to place the 7.0 mm endotracheal tube (ETT). Although direct laryngoscopy was successful, the force required to visualize her cords along with multiple attempts likely triggered her tachycardic and hypertensive response to intubation; heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) peaked at 133 beats per minute and 145/105 mmHg, respectively. The patient’s sympathetic response to laryngoscopy was successfully treated with intermittent intravenous (IV) doses of esmolol, and this β1 selective antagonist was also periodically used during the maintenance phase of anesthesia to limit increases in HR from surgical stimulation. Upon emergence from anesthesia, the patient became hypercarbic with an end-tidal CO2 level reaching 61 mmHg. Once she was breathing more regularly and her end-tidal CO2 levels normalized to 40 mmHg, she was extubated and then transported to the post-anesthesia care unit breathing spontaneously with supplemental oxygen. The patient had no further airway issues and was discharged in stable condition from the post-anesthesia care unit within an hour of arrival.

Case 2

An 86-year-old female with a BMI of 33 kg/m2 presented to the operating room to undergo a thyroidectomy for removal of a large suprasternal goiter. The thyroid mass limited her neck ROM and obstructed her airway by causing a tracheal deviation as seen on the computed tomography exam. This indicated that she would have a “difficult airway” even though the rest of her airway indices were normal. Specifically, her airway exam showed she had a Mallampati class II airway with an oral aperture of 3 fingerbreadths and a thyromental distance of 3 fingerbreadths. Since airway management was expected to be difficult, she was given 0.2 mg of IV glycopyrrolate to dry secretions, 50 mcg of fentanyl for patient comfort, and a 4% lidocaine nebulizer to topicalize her posterior pharynx prior to an awake intubation using a 5.2 mm inner diameter flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope (FFB) in order to optimize maneuverability. Within two attempts, her vocal cords were visualized and the 6.0 mm ETT was advanced through them. The finesse and maneuverability of the FFB helped to prevent hemodynamic instability by decreasing the amount of force and, presumably, number of direct laryngoscopic attempts that might have been needed if a conventional laryngoscope blade was used. The patient underwent surgical thyroidectomy without complications and was extubated awake, following complete neuromuscular blockade reversal, when she could follow commands – open her eyes and squeeze the clinician’s hand.

Both case examples demonstrate a common occurrence faced by anesthesia clinicians in the general operating room arena – patients appearing to have straightforward airways during their preoperative examinations often receive conventional airway management rather than the incorporation of specialized airway devices (SADs). Although in young and middle-aged patients this is generally deemed to be an appropriate approach, among elderly patients it could lead to undesirable events. A common complication related to difficulties with BMV is inadvertent insufflation of the abdomen with a concomitant heightened risk for aspiration. Moreover, during multiple laryngoscopic attempts, hemodynamic instability might ensue placing the elderly patient at an increased risk for myocardial ischemia. On the other hand, patients with expected airway difficulties receive SAD that limit the risk for adverse events during the induction phase of anesthesia. In Case 2, an awake FFB, using minimal sedation, was used to intubate, which not only limited the risk of aspiration by avoiding BMV but also enhanced maneuverability of the ETT, limiting the risk of a sympathetic response (eg, tachycardia and hypertension) to laryngoscopy, which occurred in Case 1. Accordingly, an increased awareness among anesthesia care providers and the formation of more appropriate “standard” or specialized techniques should be considered to decrease the risk of complications during airway management in the elderly surgical patient.

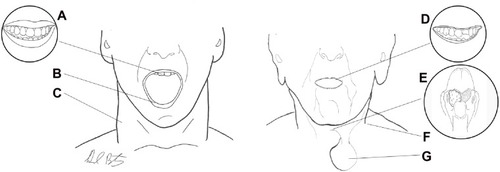

Elderly patients are prone to structural and functional changes surrounding the airway, including, but not limited to, an edentulous mouth, oropharyngeal tumors, atrophy of the glottic muscles, and decreased neck ROM ( for comparison with a younger patient).Citation1–Citation4 These attributes may make it more difficult to BMV and/or intubate during airway management. In addition, age-related comorbidities such as COPD, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and diabetes increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia.Citation5,Citation6 Diminished cognitive function from Alzheimer’s disease may impair the patient’s ability to cooperate during an awake FFB if the airway is deemed to be difficult.Citation7 Problems during airway management may be isolated to a specific aspect of care, or may include challenges related to a combination of tracheal intubation, BMV, oxygenation/desaturation, and aspiration.

Figure 1 Anatomical variation in young and elderly.

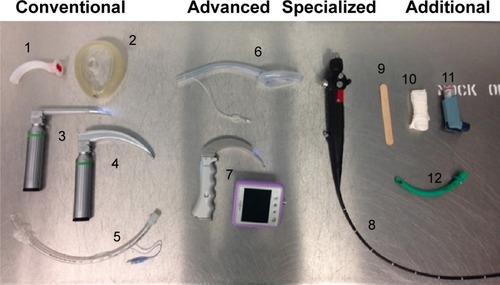

In this review, we provide the reader with a comprehensive overview of the anatomic and physiopathologic changes that may impact airway management of the elderly surgical patient. Finally, we discuss various airway devices () and corresponding management strategies () that may be considered in the armamentarium of the anesthesia care provider who oversees the perioperative course of elderly surgical patients in order to help minimize the risk of complications related to airway management in this vulnerable and growing surgical population.

Table 1 Airway devices/management strategies for the elderly patient

Figure 2 Devices for airway management.

Anatomic changes

Nasal cavity

Nasal polyps are significantly more prevalent in adults over 60 years old as compared to those younger than 40 years.Citation8 Nasal polyps, if present, may make intubation through the nostrils difficult and/or bloody.Citation9 Not only might a nasal polyp interfere with the placement of a nasopharyngeal airway or nasoendotracheal tube, the airway or tube themselves might cause the polyp to dislodge, which could then obstruct the airway.Citation10 During oral surgery and for patients with oropharyngeal/laryngeal tumors, nasal intubation is common. Since oropharyngeal tumors are also common in octogenarians, these patients may need to undergo nasal intubation; thus, it is important to ensure that the patients do not have polyps or that the nostril with the polyp is avoided.Citation2

Oral cavity

The lips are often overlooked in the elderly; however, they are prone to being lacerated due to excessive dryness and fragility. The cutis in the lip thins with age and collagen fibers also begin to separate.Citation11 This is consistent with the general tendency of the epidermis and dermis to thin with aging. Therefore, it is important to take caution while using laryngoscopes as lip lacerations are common. Accordingly, we recommend using a device with less force, such as a video laryngoscope (VL) to minimize lip damage. Additionally, atrophy of the orbicularis oris muscle occurs with advancing age which might lead to a mild facial droop near the corners of the mouth.Citation11 This age-related esthetic change could affect BMV as it may be more difficult to create a good face-mask seal about the oral cavity. If ventilation using a conventional bag mask proves to be challenging, a supralaryngeal device (SLD), such as a laryngeal mask airway (LMA), may be used. The SLD will create a better seal in the posterior pharynx and sit above the glottis, making it easier to ventilate than by BMV.

Octogenarians experience many problems with their teeth that are aging-related including periodontal disease and tooth decay. Frequently, less saliva is produced leading to a dry mouth. Since saliva acts as a source of protective minerals for teeth and inhibits the growth of bacteria, this reduction contributes to dental decay.Citation12 Approximately two-thirds of octogenarians have had tooth decay, and almost a quarter have untreated decay.Citation13 The prevalence of tooth decay and loose teeth in the elderly makes it more cumbersome to ventilate using an oral airway and/or to intubate since there is a risk of dislodging loose teeth and subsequent translocation into the trachea or esophagus. As a result, devices with less force, such as VL, should be used to decrease the chance of damage to any vulnerable-appearing teeth.

The elderly also tend to lose their teeth as they age; almost 50% of the elderly in the US need dentures, and their gums tend to shrink exposing the roots where cavities are more likely to form.Citation1 If not treated, the cavities may cause infection leading to the loss of teeth. Although the absence of teeth may make it easier to intubate; it is difficult to bag mask ventilate due to the fact that it is hard to create a seal in an edentulous patient.Citation14 The lack of seal from the mask may require higher pressures of CPAP to ventilate and thus lead to insufflation of the stomach. To avoid these complications, an SLD should be considered for ventilation in an edentulous elderly person. Although dentures, when left in place, may ease BMV, they make it more difficult to intubate and could be damaged. Because some patients may experience anxiety related to the early removal of their dentures, it is acceptable to wait until the patient is ready to be induced and/or airway management is planned.

Besides affecting the integrity of the gums and teeth, age-related alterations in salivary secretions, along with reduced vascularity, and/or less production of steroid hormones with advancing age, are a setup for oral lesions and bleeding as epithelial and connective tissue atrophy with age.Citation15 The chance for lacerations is heightened when the airway is suctioned prior to intubation and/or after extubation. Therefore, to limit the chance for mucosal trauma, we recommend using a device with less force, such as a VL. It is important to note that denture wearers might actually have excess saliva, and this is partly responsible for the development of oral ulcers and sores.Citation16 The excessive saliva may make taping the ETT more difficult as the tape will not adhere to the skin, which can cause an increased risk of displacing the tube, especially when the patient is positioned prone. Excessive secretions might also increase the chance of rotation of the SLD, leading to an ineffective seal about the laryngeal inlet. An alternative to securing an SLD such as an LMA is to place a bite block on either side and then secure the bite block-LMA-bite block together while fixing the “triad” to the skin above the upper lip with tape.

Tongue pressure (pressure exerted by the the tongue on the hard palate) is significantly decreased with age indicative of muscle fatigue, specifically of the infrahyoid and suprahyoid muscles, which may affect swallowing as well as increase the risk of aspiration.Citation3 The elderly also tend to be immunocompromised, which increases their susceptibility to oral infections such as Candida, specifically the tongue, which if present may interfere with the placement of oral airways and/or devices used for intubation; thus, we recommend suctioning prior to VL in order to enhance visualization of the vocal cords and limit irritation to the already inflamed area.Citation17

Pharyngeal/laryngeal

Oropharyngeal cancer is common in elderly patients, especially at the base of the tongue and other tonsillar regions.Citation2 As a result, it may be difficult to obtain a view of the vocal cords during intubation and/or in actually placing the ETT.Citation18 These tumors may also be present as masses on the neck, which may decrease the ROM of the neck and the distance between the thyroid notch to the tip of the jaw with the head extended, further challenging the act of direct laryngoscopy.Citation18 Therefore, use of an SAD such as a lightwand, optical stylet, or FFB to improve maneuverability, or even a VL is recommended.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) occurs in the elderly due to changes in the pharynx. There is also an increase of parapharyngeal fat accumulation due to aging independent of BMI, which leads to OSA.Citation19 It may also make intubation more difficult; therefore, a VL is suggested for better visualization of the vocal cords. In addition, the elderly experience a decrease in the genioglossus negative-pressure reflex, and since the genioglossus muscle is an upper airway dilator which protects pharyngeal patency, any impairment in this muscle or reflex increases the chances of airway obstruction and pharyngeal collapse.Citation19 As a result, it is recommended that the patient be positioned in reverse Trendelenburg to decrease the amount of force pushing directly down on the posterior pharynx, which prevents an airway collapse. OSA may create an increased risk of desaturation events, so it is imperative that it be closely monitored during airway management, by providing CPAP.

Due to aging, the number of collagen fibers and elastin fibers in the hyoepiglottic ligament is decreased, which makes the epiglottis floppier and harder to move anteriorly during direct laryngoscopy with a Macintosh blade; thus, limiting adequate visualization of the vocal cords.Citation20 As a result, if direct laryngoscopy is needed, the Miller blade is recommended over the Mac blade in the elderly. In addition, abnormalities related to the epiglottis are more common in the elderly than other age groups.Citation21 Some of these abnormalities include delayed functioning, limited movement, or lack of movement downward. Tumors in the elderly may also lead to thickening of the epiglottis, rendering it almost immobile. These all prevent the epiglottis from effectively protecting the airway; thus, increasing the risk of a difficult intubation and aspiration.Citation21 There is also a significant decrease in sensory capacity of the laryngopharynx, which when combined with motor deficits, may also lead to aspiration.Citation22 Therefore, we recommend that SLDs be used to ventilate prior to intubation, but that an ETT be placed to secure the airway during the surgical procedure in these patients who have a heightened risk of aspiration.

Neck

Changes that occur in the neck due to aging include rheumatoid arthritis, myelopathy, and development of thyroid masses, which affect rotation and ROM, making intubation more difficult.Citation4 Rheumatoid arthritis occurs mostly in the second and third cervical vertebrae, causing ligament destruction, inflammation, swelling of the synovial membrane, and atlantoaxial subluxation, making rotation difficult.Citation4 Arthritis is often associated with osteophytes, which can result in neurologic symptoms if they interfere with spinal nerves.Citation4 As people age, the intervertebral discs begin to lose their supporting capabilities and shrink; thus shortening the distance between the vertebrae.Citation23 The shortening of the discs puts stress on the cartilage of the vertebrae, causing a decrease in size of the spinal canal. This narrowing puts pressure on the spinal cord resulting in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. This results in stiffness of the neck, and may manifest as pain in the neck, arms, and shoulders.Citation23 Video laryngoscopy is recommended if there is limited neck ROM, and if there is virtually no motion in the neck; FFB should be used to enhance maneuverability for ETT placement.

The incidence of goiters increases in the elderly, and if large enough, may cause thyroid failure.Citation24 The thyroid plays a role in mental functioning, so a condition that affects the ability of the thyroid to work properly may also affect patient cooperation during airway management. Elderly patients with hypothyroidism are more likely to suffer from myxedema coma. Triggers for this type of coma may be certain medications, hospitalization, stress, and other illnesses.Citation24 Hyperthyroid issues such as Graves’ disease and toxic multinodular goiter are also common in the elderly and may cause osteoporosis, nausea and vomiting, supraventricular arrhythmias and other heart conditions, depression, and mania.Citation24 These thyroid changes affect anesthetic medications and cooperation during anesthesia management. If a thyroid mass significantly affects ROM in the neck, FFB is recommended. This can be performed while the patient is asleep or awake, depending on the patient’s mental status, cooperation, and risk of aspiration.

Previous surgeries, burns, or other lesions may cause significant scarring of the neck. Scars may limit neck ROM, making it difficult to view the vocal cords with a laryngoscope. There is also less maneuverability available, so an SAD such as an FFB would provide more maneuverability and increase the chance of success when intubating these patients.Citation25

Damage occurs in octogenarians who undergo radiation treatment of the head and neck. Radiation may decrease neck ROM, especially if they already have limited movement. Toxicity from radiation is more common in the elderly causing dysphagia and breathing complications.Citation26 Neck radiation may also increase the risk of thyroid nodules and hypothyroidism.Citation27 Thyroid diseases, as discussed earlier, have many implications for airway management. Finally, neck radiation has been associated with carotid bruits, which if associated with stroke, could impair cognitive function and/or induce dysphagia; thus, increasing the risk of aspiration.Citation27

Physiopathological changes indirectly affecting airway management

Integumentary system

As mentioned in the Oral cavity section, aging results in less collagen fiber production, making the skin thinner and frailer in the elderly.Citation11 The extracellular matrix within the dermis deteriorates with age, which impairs wound healing and increases bleeding and bruising susceptibility.Citation28 Accordingly, gentle direct laryngoscopy or better yet, use of video-assisted airway equipment and alternatives to adhesive tape (for securing the airway) are recommended.

Scleroderma, an autoimmune disease that occurs in the elderly, is characterized by the hardening and tightening of the skin.Citation29 It may make it more challenging to open the patient’s mouth for intubation, which may prompt the use of a device that has more flexibility such as an FFB. While those who develop scleroderma at a later age (>50 years) tend to have less skin involvement, they are at greater risk of having Sjögren’s syndrome.Citation29 Patients with Sjögren’s syndrome, eg, characterized by dryness of the eyes and mouth, would also benefit from a video-assisted approach to laryngoscopy.

Cardiovascular system

Progressive stiffening of the arteries and decreases in compliance of the myocardium are natural occurrences of cardiac aging due to the combined effects of glycosylation and deposition of free radicals in collagen and connective tissue, leading to a gradual loss of elasticity. Ventricular compliance is further impaired as systolic BP and pulse wave velocity increase, leading to greater impedance to ventricular outflow which is followed by left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction.Citation30 Early diastolic left ventricular filling is further impaired by reductions in myocardial relaxation.

Taken together with age-related decreases in vagal tone, increases in resting sympathetic nerve activity, and circulating levels of norepinephrine, elderly patients exhibit labile BP responses during the anesthetic induction.Citation31 HR and BP tend to increase significantly as a result of laryngeal stimulation during airway management.Citation32 To combat the sympathetic activation, a short-acting β-blocker or IV esmolol is recommended.Citation33 Indeed, a stiffened vasculature is also a setup for hypotension following bolus IV administration of such general anesthetics as propofol. To limit BP swings during propofol induction in an elderly hypertensive patient, we prefer incremental propofol dosing, eg, 25–50 mg at a time, until loss of consciousness. Using this approach, anesthetic depth can then be effectively titrated with volatile anesthetics via BMV to help ensure both hemodynamic stability and a minimal response to airway manipulation. Unlike propofol, etomidate, another hypnotic used as an induction medication, has minimal effects on the cardiovascular system. While it may be very useful in those patients with compromised intravascular volume status, coronary artery disease, or reduced ventricular function, it might not sufficiently blunt the sympathetic response to laryngoscopy, particularly if the elderly patient has underlying hypertension.Citation34 Indeed, sympathetic surges that lead to tachycardia and hypertension during difficult intubations in elderly patients with stiff ventricles and limited pulmonary venous reserve capacity could trigger pulmonary edema and even myocardial ischemia. Therefore, in addition to recommending an individualized and careful anesthetic induction, it is the authors’ contention to use an intubating device that necessitates minimal or no force, such as VL or FFB when instrumenting the airway of the elderly patient.

Pulmonary system

Besides the aforementioned upper airway dysfunction that predisposes elderly patients to airway obstruction, there are several physiologic changes of the respiratory system associated with aging that may be stressed during airway manipulation upon induction or emergence from anesthesia to be considered. With aging, chest wall compliance decreases due to structural changes of the intercostal muscles, joints, and rib–vertebral articulations that increase the work of breathing.Citation35 These changes can lead to fatigue and delayed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Airway resistance increases as the diameter of small airways decrease with age. This leads to air trapping and a greater propensity for developing intraoperative atelectasis.Citation35 Air trapping and the potential for dynamic hyperinflation during mechanical ventilation might also occur as a result of increases in lung compliance, as lung elastic recoil decreases with advancing age.Citation35 Importantly, closing volume increases even with normal tidal volume breathing which predisposes these elderly patients to hypoxemia, particularly after induction of anesthesia when mean lung volumes are reduced.Citation35 Due to increased ventilation/perfusion heterogeneity and decreased diffusing capacity, gas exchange is impaired in elderly patients predisposing them to hypoxemia.Citation36 Moreover, dysfunction of central chemoreceptors and peripheral chemoreceptors leads to a decrease in hypoxemia and hypercapnic ventilator drive. This can result in a significant increase in susceptibility to opioid-induced apnea, leading to unexpected hypoxemia and hypercapnia.Citation35 To counteract these predictable changes of aging, preoxygenation for several minutes of 100% oxygen breathing is recommended, particularly to avoid oxyhemoglobin desaturation.

In addition to the normal respiratory system changes that occur with aging, a variety of preexisting conditions prevalent in the elderly can increase their susceptibility to perioperative pulmonary complications. These conditions include smoking, OSA syndrome, asthma, and COPD.Citation6 Preoperative optimization of respiratory function may limit adverse outcomes in these patients. For instance, patients with a reversible component of airway obstruction should receive bronchodilators. If a pulmonary infection is suspected, antibiotics need to be considered. Since preoperative smoking cessation may decrease postoperative complications, this should be promoted even for a brief period before surgery.Citation37 Certainly, all patients with diagnosed OSA should have their status evaluated preoperatively, and if they are CPAP-dependent, they will need very close monitoring for oxygenation and ventilation if an awake intubation is planned. Also, they should receive CPAP treatment immediately after tracheal extubation through the placement of a nasopharyngeal airway or a CPAP machine.

Gastrointestinal system

The elderly tend to have complications with their gastrointestinal tract, especially with their esophagus. In general, there is an association of decreased motility of the esophagus with aging possibly related to the increased incidence of comorbidities (eg, diabetes and cognitive issues) that may lead to esophageal diseases. The decreased motility includes slower peristalsis and weaker peristaltic contractions.Citation38 This allows some substances to remain in the esophagus, rather than transferring completely to the stomach. In addition, it is common for gastric pressure to increase with age, which affects the pressure gradient between the stomach and the esophagus, leading to reflux.Citation38

The decrease in motility of the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter pressure both contribute to GERD, a common disease in octogenarians that may lead to aspiration. Due to other issues they present with, GERD’s effects are worse in the elderly population. For instance, the slower peristalsis increases the exposure to acid during reflux.Citation5 Also, a decrease in saliva secretion worsens the effects of the acid since saliva would help to neutralize the acid. Overall, GERD is rather prevalent in octogenarians and can lead to complications, specifically aspiration, during airway management.Citation5

Additionally, there is less nerve stimulation in the esophagus due to a decrease in the number of ganglion cells in the myenteric plexus, which leads to achalasia.Citation39 This is characterized by dilation of the esophagus and reduced relaxation. Achalasia leads to dysphagia, regurgitation, and can also contribute to GERD, and depending on the severity, achalasia can cause neck swelling, which decreases neck ROM.Citation39

Gastrointestinal diseases are common in the elderly and tend to have increased effects due to the comorbidities present. It is important to be aware of these issues as they increase the risk of aspiration during airway management. Due to the risk of aspiration, an SLD should be used to ventilate rather than a bag mask in order to decrease high pressures of CPAP and risk of insufflation of the stomach. However, an ETT should be placed to protect the airway throughout the procedure.

Renal system

Geriatric patients have an increased risk of chronic kidney disease, caused by stiffening of the arteries, resulting in increased creatinine clearance and a decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate. This may lead to hypertension under acute stress.Citation40 As a result, intubation may induce a hypertensive response, especially when multiple attempts are needed. Thus, an SAD with less force, such as a VL would be recommended to avoid this outcome.

Central nervous system

While the neurobiologic changes of aging (decreases in brain weight and volume, decreases in neurotransmitter system function, and the presence of amyloid deposits) do not lead to intellectual declines, reaction time and cognitive processing commonly slow with advancing age. These normal, age-related changes in the central nervous system rarely impact airway management unless there are pathologic components of dementia involved. With advanced age, the prevalence of dementia increases rapidly from 10% to 15% in persons aged 65 years to nearly 50% at the age of 85 years.Citation41 Whether it is due to stroke or Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive impairment may interfere with the patient’s ability to cooperate during airway management if awake FFB is required. Moreover, certain anesthetic adjuvant drugs that might be used during preparation for an awake FFB intubation, including benzodiazepine and anticholinergic drugs, may increase the risk of postoperative delirium in patients with preexisting dementia. Accordingly, sedatives should be chosen carefully and an anticholinergic that does not cross the blood–brain barrier, such as glycopyrrolate, should be considered in these instances.Citation7 Also, if possible, an “asleep” FFB is recommended if airway maneuverability is required to ensure a smooth endotracheal intubation and to decrease the risk of aspiration.

Parkinson’s disease is a common neurological disease in the elderly that has implications in airway management. Vocal fold bowing, in which the vocal cords become weak and create a gap, tend to occur in these patients.Citation42 While a smaller ETT may be considered to avoid vocal cord damage, it may be more difficult to actually ventilate the patient due to a larger air leak because of a wider gap between the cords and tube.Citation42 Also, the medication used to treat Parkinson’s, levodopa, wears off relatively quickly, and if usage is stopped before surgery, Parkinsonism symptoms, such as rigidity, may be exaggerated.Citation7 This could manifest as greater difficulties with BMV and direct laryngoscopy. Thus, an SAD such as a VL or FFB should be considered as an alternative approach in this instance.

Indeed, elderly patients with neurologic conditions may have associated dysphagia and impaired cough reflex that leads to an accentuated risk of pulmonary aspiration and the subsequent development of pneumonia.Citation43 Because the risk is compounded by the effects of anesthetics, sedatives, and narcotics, as well as any pharyngeal manipulation that occurs during airway management, precautions should be taken to avoid this complication.

Discussion

Airway management can be divided into the following: performing intubation, providing effective ventilation and oxygenation to prevent a desaturation event, and decreasing the risk of aspiration. The anatomic, physiopathologic, and cognitive changes seen in octogenarians have implications for all four aspects, making it necessary for airway management techniques to be developed for the elderly surgical patient as described in .

In the clinical airway and anesthetic management of octogenarian patients, BMV tends to be difficult and desaturation events are probable, while intubation seems to be less likely to cause difficulty. If difficult intubation is to occur, it tends to be due to either issues in the neck such as radiation and/or previous surgical scars, or due to decreased oral aperture and/or oropharyngeal tumors. If the intended device is a conventional device, it may fail and require an SAD as a rescue, which prompts the question of whether or not to use an SAD as the intended device. With that being said, SADs tend to be more suitable for the elderly surgical patient as they utilize finesse rather than force. The use of SLDs in combination with SADs is another viable option for the elderly; however, it is important to note that SADs require expertise and training that are critical in the successful use of the device. Ultimately, the extent of adverse airway outcomes that occur is likely due to the amount of anatomic and pathophysiologic issues that a patient suffers from.

Overall, there is a spectrum of elderly patients ranging from excellent health status to extremely unhealthy with multiple comorbidities. In addition, airway features degrade as a result of aging making airway management more challenging. Anesthesia clinicians should consider both the overall condition of the patient’s health and the degree of degradation that their airway has undergone to decide a management strategy. Certain elderly patients may be easy to manage with conventional devices, while others may require the use of an SLD or SAD. As described in the literature and as we have detailed earlier, geriatric patients are vulnerable during airway management. A protocol combining each aspect of airway management with specific techniques for elderly patients should be created to decrease the incidence of complications.

Acknowledgments

Leanne Groban was funded in part by Departmental Funds and R01-AG033727. Kathleen N Johnson was funded by a summer research stipend by the Department of Anesthesiology.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SimunkovićSKBorasVVPandurićJZilićIAOral health among institutionalised elderly in Zagreb, CroatiaGerodontology200522423824116329233

- WarnakulasuriyaSGlobal epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancerOral Oncol2009454–530931618804401

- HiramatsuTKataokaHOsakiMHaginoHEffect of aging on oral and swallowing function after meal consumptionClin Interv Aging20151022923525624755

- PopitzMDAnesthetic implications of chronic disease of the cervical spineAnesth Analg19978436726839052322

- AchemSRDeVaultKRGastroesophageal reflux disease and the elderlyGastroenterol Clin North Am201443114716024503365

- PeruzzaSSergiGVianelloAChronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in elderly subjects: impact on functional status and quality of lifeRespir Med200397661261712814144

- KeefoverRWAging and cognitionNeurol Clin19981636356489666041

- JohanssonLAkerlundAHolmbergKMelénIBendeMPrevalence of nasal polyps in adults: the Skövde population-based studyAnn Otol Rhinol Laryngol2003112762562912903683

- GoranovicTMilicMKnezevicPNasoendotracheal tube obstruction by a nasal polyp in emergency oral surgery: a case reportWorld J Emerg Surg200723118034893

- BinningRLetter: A hazard of blind nasal intubationAnaesthesia19742933663674835864

- PennaVStarkGBEisenhardtSUBannaschHIblherNThe aging lip: a comparative histological analysis of age-related changes in the upper lip complexPlast Reconstr Surg2009124262462819644283

- SelwitzRHIsmailAIPittsNBDental cariesLancet20073699555515917208642

- WarrenJJCowenHJWatkinsCMHandJSDental caries prevalence and dental care utilization among the very oldJ Am Dent Assoc2000131111571157911103576

- LangeronOAmourJVivienBAubrunFClinical review: management of difficult airwaysCrit Care200610624317184555

- ShklarGThe effects of aging upon oral mucosaJ Invest Dermatol19664721151205916125

- JainkittivongAAneksukVLanglaisRPOral mucosal conditions in elderly dental patientsOral Dis20028421822312206403

- LockhartSRJolySVargasKSwails-WengerJEngerLSollDRNatural defenses against Candida colonization breakdown in the oral cavities of the elderlyJ Dent Res199978485786810326730

- MatiocAAOlsonJUse of the laryngeal tube in two unexpected difficult airway situations: lingual tonsillar hyperplasia and morbid obesityCan J Anaesth200451101018102115574554

- MalhotraAHuangYFogelRAging influences on pharyngeal anatomy and physiology: the predisposition to pharyngeal collapseAm J Med2006119172.e9e1416431197

- SawatsubashiMUmezakiTKusanoKTokunagaOOdaMKomuneSAge-related changes in the hyoepiglottic ligament: functional implications based on histopathologic studyAm J Otolaryngol201031644845220015802

- GaronBRHuangZHommeyerMEckmannDSternGAOrmistonCEpiglottic dysfunction: abnormal epiglottic movement patternsDysphagia2002171576811820387

- AvivJEEffects of aging on sensitivity of the pharyngeal and supraglottic areasAm J Med19971035A74S76S9422628

- YoungWFCervical spondylotic myelopathy: a common cause of spinal cord dysfunction in older personsAm Fam Physician200062510641070107310997531

- MariottiSFranceschiCCossarizzaAPincheraAThe aging thyroidEndocr Rev19951666867158747831

- XueFSLiaoXLiCWClinical experience of airway management and tracheal intubation under general anesthesia in patients with scar contracture of the neckChin Med J (Engl)20081211198999718706246

- CooperJSFuKMarksJSilvermanSLate effects of radiation therapy in the head and neck regionInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys1995315114111647713779

- AugustMWangJPlanteDWangCCComplications associated with therapeutic neck radiationJ Oral Maxillofac Surg19965412140914158957119

- LiYLeiDSwindellWRAge-associated increase in skin fibroblast-derived prostaglandin E(2) contributes to reduced collagen levels in elderly human skinJ Invest Dermatol201513592181218825905589

- SchachnaLWigleyFMChangBWhiteBWiseRAGelberACAge and risk of pulmonary arterial hypertension in sclerodermaChest200312462098210414665486

- GrobanLDiastolic dysfunction in the older heartJ Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth200519222823615868536

- EslerMDThompsonJMKayeDMEffects of aging on the responsiveness of the human cardiac sympathetic nerves to stressorsCirculation19959123513587805237

- HabibASParkerJLMaguireAMRowbothamDJThompsonJPEffects of remifentanil and alfentanil on the cardiovascular responses to induction of anaesthesia and tracheal intubation in the elderlyBr J Anaesth200288343043311990278

- ZauggMTaglienteTLucchinettiEBeneficial effects from beta-adrenergic blockade in elderly patients undergoing noncardiac surgeryAnesthesiology19999161674168610598610

- MasoudifarMBeheshtianEComparison of cardiovascular response to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation after induction of anesthesia by Propofol and EtomidateJ Res Med Sci2013181087087424497858

- ChiamBSinDDThe aging lung: Implications for diagnosis and treatment of respiratory illnesses in the elderlyGeriatr Aging2002953640

- CardúsJBurgosFDiazOIncrease in pulmonary ventilation-perfusion inequality with age in healthy individualsAm J Respir Crit Care Med19971562 Pt 16486539279253

- MøllerAMVillebroNPedersenTTønnesenHEffect of preoperative smoking intervention on postoperative complications: a randomised clinical trialLancet2002359930111411711809253

- KhanTAShraggeBWCrispinJSLindJFEsophageal motility in the elderlyAm J Dig Dis1977221210491054930902

- QadriHMDehadarayAYKaushikMAndrabiDZAchalasia cardia: an interesting variation as a large neck swellingJ Clin Diagn Res201487KD01225177584

- MouradJJPannierBBlacherJCreatinine clearance, pulse wave velocity, carotid compliance and essential hypertensionKidney Int20015951834184111318954

- BarnettSRPolypharmacy and perioperative medications in the elderlyAnesthesiol Clin200927337738919825482

- SinclairCFGureyLEBrinMFStewartCBlitzerASurgical management of airway dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease compared with Parkinson-plus syndromesAnn Otol Rhinol Laryngol2013122529429823815045

- MarikPEAspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumoniaN Engl J Med2001344966567111228282