Abstract

Objective

In Denmark, the strategy for treatment of cancer with metastases to the liver has changed dramatically during the period 1998 to 2009, when multidisciplinary care and a number of new treatments were introduced. We therefore examined the changes in survival in Danish patients with colorectal carcinoma (CRC) or other solid tumors (non-CRC) who had liver metastases at time of diagnosis.

Study design and methods

We included patients diagnosed with liver metastases synchronous with a primary cancer (ie, a solid cancer diagnosed at the same date or within 60 days after liver metastasis diagnosis) during the period 1998 to 2009 identified through the Danish National Registry of Patients. We followed those who survived for more than 60 days in a survival analysis (n = 1021). Survival and mortality rate ratio (MRR) at 1, 3, and 5 years stratified by year of diagnosis were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis.

Results

In the total study population of 1021 patients, 541 patients had a primary CRC and 480 patients non-CRC. Overall, the 5-year survival improved from 3% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1%–6%) in 1998–2000 to 10% (95% CI: 6%–14%) in 2007 to 2009 (predicted value). The 5-year survival for CRC-patients improved from 1% (95% CI: 0%–5%) to 11% (95% CI: 6%–18%) whereas survival for non-CRC patients only increased from 5% (95% CI: 1%–10%) to 8% (95% CI: 4%–14%).

Conclusion

We observed improved survival in patients with liver metastases in a time period characterized by introduction of a structured multidisciplinary care and improved treatment options. The survival gain was most prominent for CRC-patients.

Introduction

The liver is a common site of metastases and gastrointestinal-, lung- and breast cancers frequently give rise to liver metastases.Citation1 Liver metastasis is usually considered to be a manifestation of end stage disease. However, in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) metastases, the disease often presents with oligometastases relatively early on and the liver is often the only site of metastasis. Hence, at the time of CRC-diagnosis, 15% of patients have metastases to the liver and in approximately 75% of these, the metastases are confined to the liver.Citation2 In general, systemic therapy is the preferred treatment for most patients with liver metastases, but patients with a limited number and size of the metastases and with favorable histology, especially CRC, should be considered for focal therapy.Citation3–Citation7 A large number of systemic therapies for patients with metastatic cancer have been introduced during the last 10 years and over the same period surgery and nonsurgical techniques for focal ablation of metastases in the liver have improved considerably.Citation8

The Danish National Board of Health launched The National Cancer Treatment Plans I and II in 2000 and 2005 aiming at improving cancer treatment in the country.Citation9 The major issues were improvements in diagnostics, surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy for cancer, and major government investments have followed the program. Assessing whether these efforts have resulted in real improvement in terms of survival outcomes is thus of great interest. We therefore conducted a cohort study in Northern Denmark to study time changes in survival in patients with liver metastases synchronously to CRC and non-CRC during 1998 to 2009. We chose only to evaluate patients with synchronous liver metastases because metachronous metastases are known to be incompletely registered. Due to differences in biology and therapy options, the study evaluated patients with CRC and non-CRC liver metastases separately.

Material and methods

The study was conducted in the Central and the North Denmark Regions (2 of 5 Danish regions), with a combined population of 1.8 million. The National Health Service provides tax-supported health care for all inhabitants of Denmark, guaranteeing free access to hospitals. A 10-digit civil registration number has been assigned to all residents by the Central Office of Civil Registration since 1968.Citation10 This number, unique to each Danish resident, is used in all Danish registries, allowing unambiguous individual-level data linkage.

Identification of liver metastases cancer patients

Through the Danish National Registry of Patients (DNRP), we identified all patients who had a first time diagnosis of liver metastases in the period January 1, 1998 through December 31, 2009 and no previous cancer diagnosis recorded in the DNRP. DNRP contains information about all admissions from nonpsychiatric hospitals in Denmark since 1977.Citation11 Outpatient and emergency room visits at hospitals have been included since 1995. This registry includes information on civil registration number, dates of admission and discharge, surgical procedure(s) performed, and up to 20 diagnoses from each hospital contact. Diagnoses have since 1994 been classified according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10th edition. The ICD-10 codes used to identify patients with liver metastases was C78.7 and additional codes used for identification of the primary cancers were C18-21 (CRC/anal cancer) and C00-17; and C22-97 (non-CRC).Citation12 We restricted our study population to patients considered to have synchronous metastases, defined by being registered with a code for a primary cancer at date of liver metastasis diagnosis or within 60 days thereafter.

Survival

Survival status and eventual date of death for all included patients was obtained through the Civil Registration System. Since 1968, this system has kept electronic records, updated daily, on date of birth, date of emigration, and vital status for all residents. Data linkage was performed using the civil registration number as identification number.

Statistical analysis

Because we defined our population as patients with a primary cancer diagnosed at date of liver metastasis diagnosis or up to 60 days thereafter, we started our follow-up 60 days after metastasis diagnosis. We followed each patient until emigration, death, or 25 June 2010, whichever came first. To visualize crude survival we constructed Kaplan–Meier curves stratified according to period of diagnosis (1998–2000, 2001–2003, 2004–2006, and 2007–2009). We estimated 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival. In the latter periods we estimated 3- and 5-year survival using a hybrid analysis in which we included the actual survival for as long as possible and then estimated the conditional probability of surviving thereafter based on the corresponding survival experience of patients in the previous period (ie, using a period analysis technique).Citation13 To compare mortality over time we used Cox proportional hazards regression analysis with 1998 to 2000 as the reference period to estimate the MRR and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) adjusting for age (15–59 years, 60–74 years, 75+ years) and gender. The assumptions of proportional hazards were examined graphically by plotting observed and simulated paths of the standardized score process.

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

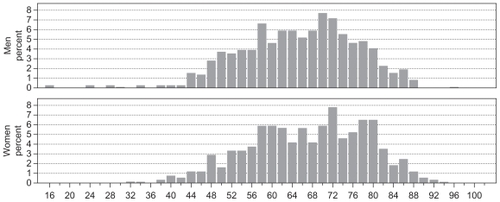

The study cohort comprised a total number of 1021 patients identified with synchronous liver metastases during the 12 year period 1998 to 2009 in the Central and North Denmark Regions who all survived at least 60 days after date of diagnosis. The largest group of patients (n = 541; 53.0%) were diagnosed with CRC as primary cancer whereas the remaining non-CRC patients represented a variety of tumor sites (n = 480; 47.0%). In the same time period 15,097 patients were registered with primary CRC (colon cancer or rectal cancer; ICD: C18-19 or C20-21) in the Central and North Denmark Regions. The distribution of patients according to the primary tumor site is listed in . The non-CRC group was dominated by patients with primary gastro-intestinal and lung cancer, whereas only 2.2% had a primary breast cancer. In the total cohort the median age was 66.8 (range 15.3–95.3) years () with a male/female distribution of 54%/46%. The median age was 67.7 (range 27.0–93.2) and 66.2 (range 15.3–95.3) years and the male/female distribution 53%/47% and 55%/45% for the CRC and non-CRC cohorts, respectively.

Figure 1 Age distribution of the total cohort of 1021 patients diagnosed with liver metastases, Denmark 1998 to 2009.

Table 1 Patients with synchronous liver metastasis by primary tumor site, Northern Denmark 1998 to 2009

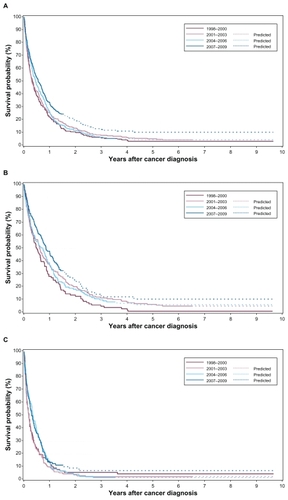

For patients with synchronous liver metastases, the overall survival improved over the 12-year period (). This was most pronounced during 2007 to 2009. Over the time period 1998 to 2009, the 5-year survival improved from 3% (95% CI: 1%–6%) to 10% (95% CI: 6%–14%) (predicted value). The 5-year survival of CRC-patientsimproved from 1% (95% CI: 0%–5%) to 11% (95% CI: 6%–18%) () whereas the increase of survival for non-CRC patients was 5% (95% CI: 1%–10%) to 8% (95% CI: 4%–14%) ().

Table 2 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival and mortality rate ratio (MRR) adjusted for age and gender for Danish patients with liver metastases stratified by period of diagnosis

Table 3 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival and mortality rate ratio (MRR) adjusted for age and gender for the cohort of colorectal carcinoma liver metastasis patients stratified by period of diagnosis

Table 4 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival and mortality rate ratio (MRR) adjusted for age and gender for the cohort of non-colorectal carcinoma liver metastasis patients stratified by period of diagnosis

MRRs adjusted for age and gender in 2007 to 2009 were 0.74 (95% CI: 0.60–0.92), 0.75 (95% CI: 0.62–0.91) and 0.75 (95% CI: 0.62–0.90) after 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively, compared with 1998–2000 (, ). For CRC patients () the age and gender adjusted MRRs were 0.62 (95% CI: 0.45–0.85), 0.68 (95% CI: 0.52–0.88), and 0.66 (95% CI: 0.51–0.86) after 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively, over the same time period (). For non-CRC patients the adjusted MRRs were 0.83 (95% CI: 0.62–1.11), 0.82 (95% CI: 0.62–1.08), and 0.81 (95% CI: 0.62–1.07), respectively ().

Figure 2 Crude survival of A) the total patient cohort with synchronous liver metastases (n = 1021), B) the cohort of colorectal cancer (CRC)-patients with synchronous liver metastases (n = 541), and C) the cohort of non-CRC patients with synchronous liver metastases (n = 480), stratified by period of diagnosis.

Discussion

In this population-based study from Northern Denmark we found that the prognosis in patients with liver metastases diagnosed synchronously with CRC or other solid tumors improved from 1998 to 2009. Overall, 1-, 3- and 5-year mortality decreased approximately 25% for the total group and among CRC patients the mortality decreased nearly 35%.

Different factors affected the interpretation of our results. We conducted a population-based study in a uniform health care system with a well-defined catchment area and had data on a population of patients treated over more than a decade. Moreover, we had virtually complete follow-up for mortality. However, our study also had limitations. The registration of liver metastases in DNRP may not be complete and may have changed during the study period. Since completeness of liver metastases in DNPR may differ by disease severity our survival estimates could be inaccurate. Nevertheless, the annual number of CRC patients with synchronous liver metastases did not increase during our study period which speaks against major differences in completeness with time. Therefore, we do not expect differences in completeness of registration to explain the improved survival in CRC patients. Among non-CRC patients the annual number of patients increased. If this was caused by inclusion of more patients with less advanced liver metastases diagnosed earlier the observed improvement in survival among non-CRC patients could be explained by lead time bias. Furthermore, we only included patients with liver metastases at time of cancer diagnosis and did not include patients with liver metastases diagnosed after resection of the primary tumor (ie, metachronous metastases) so we are unable to evaluate the effect in these patients. In order to provide more up-to-date information on long-term survival we used a hybrid analysis rather than a traditional analysis. Traditionally, the 5-year survival would be derived only from patients who had been observed for 5 years or more, thereby not reflecting more recent improvements in survival. The weakness of the hybrid analysis is that it may not be as accurate as directly observed survival. However, since we based our predictions on the survival experience in the previous period of our study we expect these predictions to be conservative estimates of the improved survival.

Imaging technology used for diagnosis of liver metastases has improved during the period. Computer tomography and magnetic resonance imaging which are considered the best imaging modalities in diagnosis and staging of liver metastases have improved over time,Citation14 and for ultrasound utilization of contrast enhancement has increased the diagnostic accuracy.Citation15 However, since the numbers of new cases did not change for CRC, we find it unlikely that improvement of imaging technology is responsible for the entire increased number of non-CRC patients with liver metastases as noticed in the present study. In this regards, we find it most likely that the study population represents a steady-state population and that the survival benefit is caused by improved therapy.

An improvement in survival is likely to be a result of the many treatments that are offered to the patients over the entire course of the disease. During the time period of the present study a multidisciplinary team was introduced for treatment of liver tumors and the therapy for liver tumors was evolving over the period. Historical studies have shown that long-term survival can be achieved in patients undergoing surgical resection of oligometastases to the liver.Citation3–Citation5 Patients who are technically operable should therefore be offered a surgical resection. Novel surgical techniques have increased the number of patients who are technically operable.Citation16,Citation17 However, only approximately 25% of patients with CRC liver metastases are amenable to surgical resection.Citation18 Nonsurgical ablation techniques, such as radiofrequency ablation or stereotactic body radiation therapy are frequently used to treat patients with unresectable liver metastases in Denmark.Citation19,Citation20 Still, the efficacy of surgery and nonsurgical tumor ablation has never been proven in randomized trials.

Traditionally, metastatic cancer is treated by systemic therapies and chemotherapy has improved considerably during the last decade. For CRC patients, chemotherapy and targeted therapy to patients with metastatic cancer may improve survival, lessen symptoms related to the disease, improve quality of life and downsize liver-only metastases in patients with nonresectable metastases that potentially may become resectable.Citation21 And for patients with metastatic non- CRC, new cytostatic agents, hormonal agents, and biological therapies have resulted in survival benefit.Citation22

In conclusion our study indicates an improvement in survival for liver metastases patients during the 12 years from 1998 to 2009. The survival gain for CRC liver metastasis patients may be a result of intensified efforts in the multidisciplinary care of patients who benefit from improved systemic therapy and more aggressive approach in resection or ablation of the liver metastases.

Acknowledgments

The study received financial support from the Karen Elise Jensen Foundation, Department of Clinical Epidemiology’s Research Foundation and the Regional Clinical Epidemiological Monitoring Initiative for Central and North Denmark Regions.

Disclosure

Morten Høyer is supported by grants from AP Møller and hustru Chastine McKinney Møllers Fond for Almene Formål og the Lundbeck Foundation Centre for Interventional Research in Radiation Oncology (CIRRO).

References

- HessKRVaradhacharyGRTaylorSHMetastatic patterns in adenocarcinomaCancer200610671624163316518827

- ManfrediSLepageCHatemCCoatmeurOFaivreJBouvierAMEpidemiology and management of liver metastases from colorectal cancerAnn Surg2006244225425916858188

- FongYFortnerJSunRLBrennanMFBlumgartLHClinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive casesAnn Surg1999230330931810493478

- HouseMGItoHGonenMSurvival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: trends in outcomes for 1,600 patients during two decades at a single institutionJ Am Coll Surg2010210574474520421043

- NordlingerBGuiguetMVaillantJCSurgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver. A prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Association Francaise de ChirurgieCancer1996777125412628608500

- SmithMDMcCallJLSystematic review of tumour number and outcome after radical treatment of colorectal liver metastasesBr J Surg200996101101111319787755

- WongSLManguPBChotiMAAmerican Society of Clinical Oncology 2009 clinical evidence review on radiofrequency ablation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancerJ Clin Oncol201028349350819841322

- CunninghamDAtkinWLenzHJColorectal cancerLancet201037597191030104720304247

- SundhedsstyrelsenCancer Treatment Plans in Denmark http://www.sst.dk/2011

- PedersenCBGotzscheHMollerJOMortensenPBThe Danish Civil Registration System: a cohort of eight million personsDan Med Bull200653444144917150149

- AndersenTFMadsenMJorgensenJMellemkjoerLOlsenJHThe Danish National Hospital Register: a valuable source of data for modern health sciencesDan Med Bull199946326326810421985

- WHOInternational Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/2011

- BrennerHRachetBHybrid analysis for up-to-date long-term survival rates in cancer registries with delayed recording of incident casesEur J Cancer200440162494250115519525

- FlorianiITorriVRulliEPerformance of imaging modalities in diagnosis of liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Magn Reson Imaging2010311193120027569

- LarsenLPRole of contrast enhanced ultrasonography in the assessment of hepatic metastases: A reviewWorld J Hepatol20102181521160951

- ChunYSVautheyJNExtending the frontiers of resectability in advanced colorectal cancerEur J Surg Oncol200733Suppl 2S52S5818006265

- KhatriVPPetrelliNJBelghitiJExtending the frontiers of surgical therapy for hepatic colorectal metastases: is there a limit?J Clin Oncol200523338490849916230676

- ScheeleJStangRTendorf-HofmannAPaulMResection of colorectal liver metastasesWorld J Surg199519159717740812

- SorensenSMMortensenFVNielsenDTRadiofrequency ablation of colorectal liver metastases: long-term survivalActa Radiol200748325325817453491

- HoyerMRoedHTrabergHAPhase II study on stereotactic body radiotherapy of colorectal metastasesActa Oncol200645782383016982546

- PaganiOSenkusEWoodWInternational guidelines for management of metastatic breast cancer: can metastatic breast cancer be cured?J Natl Cancer Inst2010102745646320220104

- D’AddarioGFruhMReckMBaumannPKlepetkoWFelipEMetastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-upAnn Oncol201021Suppl 5v116v11920555059