Abstract

Background

Two-stage revision is regarded by many as the best treatment of chronic infection in hip arthroplasties. Some international reports, however, have advocated one-stage revision. No systematic review or meta-analysis has ever compared the risk of reinfection following one-stage and two-stage revisions for chronic infection in hip arthroplasties.

Methods

The review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. Relevant studies were identified using PubMed and Embase. We assessed studies that included patients with a chronic infection of a hip arthroplasty treated with either one-stage or two-stage revision and with available data on occurrence of reinfections. We performed a meta-analysis estimating absolute risk of reinfection using a random-effects model.

Results

We identified 36 studies eligible for inclusion. None were randomized controlled trials or comparative studies. The patients in these studies had received either one-stage revision (n = 375) or two-stage revision (n = 929). Reinfection occurred with an estimated absolute risk of 13.1% (95% confidence interval: 10.0%–17.1%) in the one-stage cohort and 10.4% (95% confidence interval: 8.5%–12.7%) in the two-stage cohort. The methodological quality of most included studies was considered low, with insufficient data to evaluate confounding factors.

Conclusions

Our results may indicate three additional reinfections per 100 reimplanted patients when performing a one-stage versus two-stage revision. However, the risk estimates were statistically imprecise and the quality of underlying data low, demonstrating the lack of clear evidence that two-stage revision is superior to one-stage revision among patients with chronically infected hip arthroplasties. This systematic review underscores the need for improvement in reporting and collection of high-quality data and for large comparative prospective studies on this issue.

Introduction

Much has been written in past decades on the treatment of infected hip arthroplasties (HA), as infection constitutes a major cause of revision.Citation1 The incidence of deep infection following HA has stabilized at less than 1%.Citation2–Citation5 This severe complication to an otherwise very successful procedure is a large personal and economic burden to the patient and very costly from a societal perspective.Citation4,Citation6,Citation7 Current treatment options involve a panel of surgical and nonsurgical approaches.Citation8 Antibiotic suppression therapy is used if the patient is very ill or declines further surgical treatment.Citation8,Citation9 Debridement and antibiotic treatment combined with implant retention is used in early and acute hematogenous infections, but is inferior in chronic infections.Citation10–Citation12 Direct exchange (one-stage revision) or delayed reimplantations (primarily as two-stage revision) are used in chronic infections. Two-stage revision is currently regarded as the surgical gold standard worldwide.Citation8,Citation9,Citation13–Citation16 The one-stage approach, pioneered by Buchholz three decades ago, is advocated mainly by European centers.Citation15,Citation17 One-stage revision has the presumed advantages of a lower personal burden for the patient, a societal economic gain, and an overall better outcome due to fewer surgical procedures and lack of an interim period. The last large review on one-stage revision in the treatment of infected HA was published a decade ago.Citation18 The authors concluded on the basis of 1299 episodes of infected HA treated by one-stage revision that the indication for one-stage revision was limited due to a high reinfection risk (17% reinfected). The risk estimate was obtained by pooling cases from twelve studies. Cases represented a mixture of acute and chronic infections, and no evaluation of the quality of the research data was performed. Furthermore, no direct comparison was made with other treatment strategies. We found it appropriate to investigate systematically the current evidence for best practice in the treatment of chronic infections in HA, with a focus on retention of a functional hip implant. We performed, to our knowledge, the first systematic review and meta-analysis comparing the risk of reinfection following one-stage and two-stage revision for chronic infection in HA.

Materials and methods

The study was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis.Citation19,Citation20 Our aim was to examine whether one-stage revision is a relevant treatment strategy for chronic infection in HA with respect to the primary-outcome reinfection, as compared to the currently accepted gold standard of two-stage revision. All types of study designs were accepted for inclusion in this review.

Search strategy

Studies were identified by electronic-database searching of PubMed (1966–May 2010), Embase (1980–May 2010), the Cochrane Library, and the World Health Organization platform for international clinical trials registries (http://www.who.int/ictrp). We used a search strategy developed by the first author and a university research librarian, as specified in .Citation21

Table 1 Search strategy

Reference lists of all acquired original and review articles were assessed for relevance and cross-referenced with articles already obtained (“snowballing”). Studies were subjectively assessed by title in the electronic-database search (see criteria used in ), and if deemed relevant, the abstract was retrieved. In cases of possible relevance based on the abstract, the full-length text was obtained. In cases where no abstract was available, the full-length text was obtained.

Eligibility criteria

From the full-length texts obtained, we included all studies that examined patients with an HA and a diagnosed infection of the implant, for whom a defined duration of symptoms or time period from the index implantation to the infection diagnosis was given, who were treated with either one-stage or two-stage revision, and for whom data on occurrence and number of reinfections were available. Selected relevant patient subgroups from broader studies were also able to be included. No restrictions were made according to age, gender, presence of comorbidity, infecting microorganism, primary hip disease, and nature of the index implant or length of patient follow-up. We did not include patients who had received treatment for a new infection following a prior septic revision, regardless of time interval, or patients who did not complete a reimplantation as part of a planned two-stage revision but were discharged following a Girdlestone/permanent-spacer procedure. We chose to compare only patients with completed one-stage and completed two-stage revision, as we considered this the clinically relevant treatment exposure of interest. Only patients reported in full-length articles were included for analysis. Studies with overlapping patient data were individually assessed and the most appropriate study chosen for inclusion (based on available information and longest follow-up). Eligibility assessment was done by the first author.

Data processing

The following variables were registered: (1) main exposure – patients undergoing one-stage/two-stage revision with completed reimplantation; (2) primary outcome – reinfection; (3) study demographics – first author, publication year, the institution where patients were operated on, the calendar period of inclusion, presence of a study hypothesis, a predefined primary end point, clearly defined in- and exclusion criteria, study design, retrospective or prospective data collection; (4) study population demographics – definition of infection, defined time period between latest surgery to the hip and subsequent infection, duration of infection symptoms prior to revision, the total number of patients eligible for reimplantation, study size (total number of patients receiving reimplantation), gender, age, patient comorbidity, data on the infected index HA (primary/revision and cemented/cementless), revision for other cause than infection after reimplantation; and (5) perioperative setting – type of implant used at reimplantation (cemented/cementless), follow-up period, microbiological cultures for individual patients, patient assessment score after revision surgery, time interval between stages, the use of spacer/beads or other topical antibiotics, antibiotic treatment regimen. Data were extracted independently by the first and second authors. Disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Summary measures

We performed meta-analysis estimating the absolute risk (hereafter referred to simply as “risk”) with 95% confidence intervals of the primary outcome with a random-effects model. The analysis was performed using extracted patient data from the individual studies. Subgroup analysis on the risk of reinfection was done for main exposure and further stratified by type of implant used at reimplantation. We performed meta-regression for all studies and stratified by main exposure regarding study size and publication year on risk of reinfection. We performed sensitivity analysis by means of “one-study removed” to detect outliers and evaluate single-study impact on the derived estimates. By a priori acknowledgment of significant inconsistency among studies and by taking this into account using a random-effects model, we did not further quantify existing heterogeneity.Citation22 All data management was done using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (v2.0; BioStat, Englewood, NJ). In the case of zero-outcome events, this program adds 0.5 to the value of both outcome events and sample size and uses these modified values for all future calculations (eg, no events in 20 patients: 0.5/20.5 = risk of 0.024). Forest plots were produced to qualitatively evaluate study heterogeneity and graphically support risk estimates. Funnel plots were used to graphically assess the possibility of publication bias. Such bias was believed a priori to exist for small studies with poor results.Citation23 Assessment of methodological or clinical limitations for the included studies was done with a focus on key study features, these being: (1) patient sample – well-defined inclusion criteria, mode of data collection, defined patient demographics; (2) follow-up – sufficiently defined as more than 2 years; (3) outcome – adequate description regarding infection diagnosis; and (4) treatment – perioperative treatment regimens.Citation20,Citation21

Results

Study selection

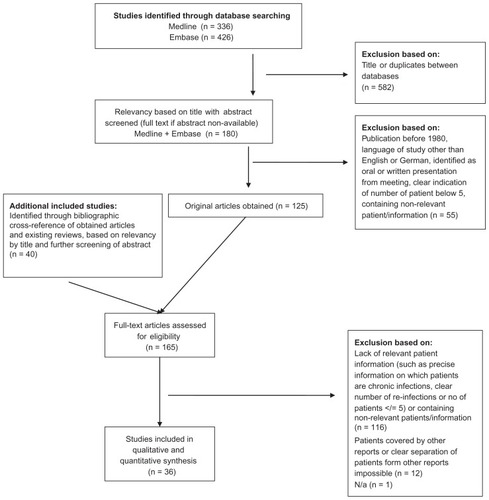

A total of 165 full-length articles were assessed for eligibility (). Of these, 36 studies were considered eligible for inclusion in the review. Of the 36 included studies, 31 (86%) were identified by the electronic-database search. The World Health Organization search revealed one relevant ongoing trial (Cementless One-Stage Revision of the Chronic Infected Hip Arthroplasty; NCT01015365). No relevant completed or terminated trials were registered. The search of the Cochrane Library revealed no further relevant studies. The cross-referenced reviews were acquired as part of background research.Citation8,Citation9,Citation14,Citation15,Citation18,Citation24–Citation46

Description of included studies

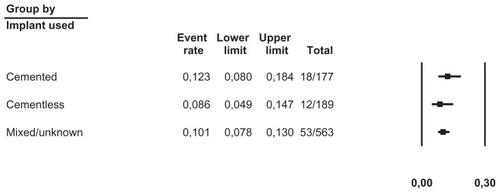

Study characteristics are summarized in and . The patients in the 36 included studies were divided into two cohorts of distinctly separate revision strategies: a one-stage- revision cohort () comprising relevant patients from ten studies (n = 375 [cementless reimplantation, n = 25 patients;Citation47–Citation49 cemented reimplantation, n = 350 patientsCitation49–Citation55]) and a two-stage-revision cohort () comprising relevant patients from 28 studies (n = 929 [cementless reimplantation, n = 189 patients;Citation48,Citation56–Citation62 cemented reimplantation, n = 177 patients;Citation63–Citation69 no specific information on type of reimplantation at patient level, n = 563 patientsCitation11,Citation13,Citation16,Citation70–Citation78]). Gender and age did not differ between the cohorts based on the available data. In the one-stage cohort, 195 of 365 (53.4%) patients were male, compared to 400 of 699 (57.2%) patients in the two-stage cohort, although 230 of 929 (24.8%) patients in the two-stage cohort had no data on gender, compared to ten of 375 patients in the one-stage cohort. The reported average age in the one-stage cohort was 61.4 years, compared to 63.1 years in the two-stage cohort. Data on comorbidity on a patient level or for the study cohort as a whole were only available in 14 studies (in only one of ten studies with patients in the one-stage cohort, compared to 14 of 28 studies with patients in the two-stage cohort). Thirteen of the 36 studies originated from North America, eleven from Europe, nine from Asia/Australia and three from South America. In the one-stage cohort, 280 of 375 (75.0%) patients originated from European studies, as did 261 of 929 (28.1%) in the two-stage cohort. In contrast, only 44 of 375 (11.7%) patients in the one-stage cohort and 445 of 929 (48.0%) patients in the two-stage cohort originated from North American studies. The one-stage cohort studies tended to be older: six of ten studies were published in the period 1990–1999 and three of ten studies were published after 1999, whereas in the two-stage cohort seven of 28 studies were published in the period 1990–1999 and 20 of 28 studies after 1999. Regarding the methodology of the included studies, we found no comparative studies that compared patients exposed to one-stage revision with a concurrent or historical control group of patients with two-stage revision, or vice versa. One study was a randomized trial of spacer versus no-spacer treatment in patients who had all had two-stage revision.Citation16 Another study was a case-control study in patients with performed two-stage revision had become infected with resistant versus nonresistant microorganisms.Citation73 One study used cohort-outcome analysis to examine predictors of reinfection.Citation63 The remaining 33 of the 36 (92%) studies were purely descriptive case series of infected HA patients treated with one-stage or two-stage revision, reporting patient characteristics and frequencies of different outcomes, including reinfection. Twenty-eight of 36 (78%) studies used retrospective data collection. Only two studies described a priori defined primary end points. Three studies stated a study hypothesis, and 14 studies provided some degree of background information on in-and exclusion criteria for enrollment in the study. Eighteen studies did not report on the status of the infected index HA (being a primary/revision or cemented/cementless prosthesis). Fifteen studies evaluated the revision procedure by means of the Harris hip score.Citation11,Citation16,Citation47,Citation48,Citation50,Citation57–Citation59,Citation61,Citation64,Citation68–Citation70,Citation77,Citation79 Twelve studies did not use a standardized scoring system in evaluating patients postoperatively.Citation13,Citation51,Citation52,Citation55,Citation60,Citation63,Citation65,Citation66,Citation71–Citation73,Citation80 Four studies used the Merle d’Aubigné–Postel score.Citation49,Citation54,Citation56,Citation75 The remaining five studies used other scoring systems.Citation53,Citation62,Citation67,Citation74,Citation78 Methodological characteristics of the included studies are shown in . In conclusion, methodological quality was considered low for most included studies, and we found no comparative studies examining one-stage versus two-stage revision.

Table 2 Characteristics of studies with patients in the one-stage revision cohort

Table 3 Characteristics of studies with patients in the two-stage-revision cohort

Table 4 Methodological characteristics of included studies

Meta-analysis

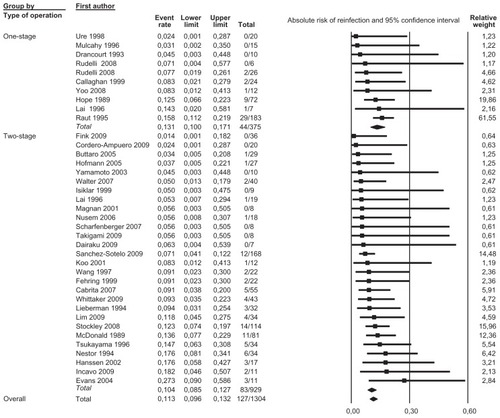

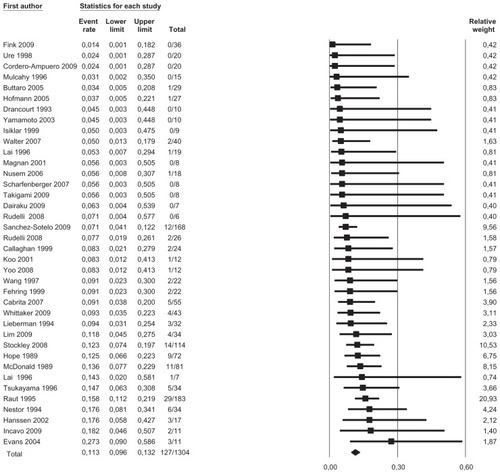

We pooled data from 36 studies with a total of 1304 patients having a completed one-stage or two-stage revision and 126 registered reinfections following the reimplantation. Sensitivity analysis did not detect outliers, nor did it indicate that any estimate was heavily determined by a particular study. We found that reinfections for all studies occurred with an estimated risk of 11.3% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 9.6%–13.2%) (). Reinfection occurred with an estimated risk of 13.1% (95% CI: 10.0%–17.1%) in the one-stage cohort and with an estimated risk of 10.4% (95% CI: 8.5%–12.7%) in the two-stage cohort (). In the two-stage cohort, cementless reimplantation yielded a reinfection risk of 8.6% (95% CI: 4.9%–14.7%), and cemented reimplantation a reinfection risk of 12.3% (95% CI: 8.0%–18.4%) (). In the one-stage cohort, only very limited data were available for cementless reimplantation (a total of just 25 cases). Meta-regression showed no correlation between study size and risk of reinfection pooling all studies (β = 0.002, P = 0.172) or within the two-stage cohort (β = −0.002, P = 0.486). However, within the one-stage cohort, a larger study size correlated with a higher risk of reinfection (β = 0.005, P = 0.048). Further exploration showed that the single study by Raut et alCitation54 had a considerable role in this correlation, with a relative weight of 62% in the one-stage group; however, this was not detected as statistically significant by sensitivity analysis. Meta-regression indicated that a more recent publication pooling all studies correlated with a lower risk of reinfection (β = −0.029, P = 0.020), but no correlation could be identified when stratified (one-stage cohort: β = −0.032, P = 0.346; two-stage cohort: β = −0.026, P = 0.098). Graphical evaluation of funnel plots confirmed the likely presence of missing smaller studies with higher reinfection risk.

Figure 2 Forest plot illustrating absolute risk of reinfection in ascending order with relative weight of individual studies.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

The results of this meta-analysis suggest the presence of nearly three additional reinfections per 100 reimplanted patients when performing a one-stage revision compared to a two-stage revision strategy for treatment of chronic infection in HA. However, we believe it is difficult to draw any conclusions on the superiority of either revision strategy from the available data. Even with the reasonably large number of studies, the pooled reinfection-risk estimates were statistically imprecise, with overlapping confidence intervals. Furthermore, one must consider that these risk estimates are based purely on data from case series with limited information on potential confounding factors. No single study has directly compared the two revision strategies. Also, the different clinical settings and patients underlying the two revision strategies must be taken into account. Nevertheless, we have demonstrated the lack of clear evidence proving one-stage revision to be a less effective treatment strategy for chronic infections in HA, as has been previously claimed.Citation18

Strengths and limitations

The data presented in this review are the best available at present to clinicians worldwide, and have so far been used to advocate the different treatment strategies offered.Citation9,Citation18 We quantified these data for the first time in a systematic review and meta-analysis. Yet it became apparent that neither controlled clinical trials nor observational studies have directly compared one-stage and two-stage revision for treatment of chronic infections in HA. The estimates obtained in this review are obtained from a wide diversity of patients, the majority of studies were small and based on retrospective data collection, and results from the two cohorts should be compared with great caution. Due to the unavailability of confounding factors in many of the studies, we chose simply to estimate pooled absolute risks of reinfection in the two cohorts, rather than a risk-ratio estimate in a direct comparison, as we had no way to control for potentially skewed distribution of covariates. Ignoring this would in our opinion compromise the entire study. We thus believe the reported absolute estimate gives a fair opportunity for better understanding the conclusions drawn from this review.Citation81 Yet several aspects must be emphasized.

Terminology

Infection in HA is by far the most difficult area to define, as this is often covered by a multitude of overlapping symptoms and clinical findings, which added together strongly indicate a septic complication. Even the gold standard in diagnosing infection – perioperative cultures – is not absolute. Culture-negative patients may still be infected, and single- or even double-positive culture may represent contamination.Citation82,Citation83 Several different definitions of infection have been used in the included studies ( and ). We chose a pragmatic approach for our review, and defined the presence of infection as defined by the authors of the individual study. However, as the definition of infection and reinfection in the 36 included studies varied considerably, ranging from “infection”/clinical features of infection to obtainment of positive bacterial cultures, the risk of misclassification is inherent. For example, patients with aseptic loosening may have been misclassified as reinfected, whereas patients with true infection who did not undergo reoperation after revision may have been missed. Many definitions of “chronic infection” exist.Citation8,Citation11,Citation13,Citation29,Citation45,Citation84–Citation86,Citation87 A priori, we aimed to define chronic infections according to McPherson, as infections with a duration of symptoms above 4 weeks, regardless of origin.Citation88 This has also been advocated by others as the best definition at present and has been used recently, in studies of arthroplasty infections and HA studies in particular, by multiple international orthopaedic centers.Citation13,Citation26,Citation77,Citation89–Citation91 However, during study selection, it became apparent that the definition by McPhersonCitation88 was very difficult to apply to the existing literature, as many studies reported only the interval from last operation to subsequent revision or from last operation to diagnosis of infection. Subsequently, we also chose to include studies that defined chronic infections as more than 1 month since last surgery, regardless of symptom duration, and by authors stating an infection as chronic ( and ).Citation11 If no data were available regarding these time limits, the study or patients were not included in our review. Thus we may have included patients with acute hematogenous infections, and we may have excluded potentially eligible patients from our analysis. A very strict definition of chronic infection at patient level is thus an element not taken into account in this analysis, as these data were not available to the authors.

Risk-factor assessment

Many apparent risk factors have been suggested to predict worse outcomes when treating infected hip arthroplasties, but few have been validated and the quality of evidence is poor.Citation5 Concerning the present study, 60% of studies in the one-stage cohort were published in the period 1990–1999, while 71% of studies in the two-stage cohort were published after 1999. A generally decreased risk of reinfection over time may have led to an overestimation of the reinfection risk associated with one-stage procedures conducted many years ago. As our understanding of the importance of many different treatment aspects increases over time, so may our overall results improve, regardless of the chosen surgical strategy. The articles from which data are analyzed span more than two decades; surgical techniques and materials used have evolved, as well as general knowledge on infections and patient care. Undoubtedly, better knowledge of optimal antibiotic therapy in prophylactic and active treatment, eg, the use of antibiotic-enriched cement and differences in local resistance patterns, but also the emergence of multiresistant organisms, could have influenced the reinfection risk over time. Improved understanding of biofilm-producing microorganisms is essential in today’s aggressive debridement approach, recognizing the need for absolute removal of dead matter and foreign materials. Our review does not take these important developments over time into account, as good data on these risk factors do not exist in the present studies. Comorbidity, high American Society of Anesthesiologists score, long duration of the surgical procedure, and low hospital and surgeon volume have been suggested as important risk factors for reinfection.Citation5 In contrast, gender or increased age apparently do not constitute important risk factors, but data quality is poor and conflicting evidence exists.Citation5,Citation92 Age and gender were also quite evenly distributed in the one-stage and two-stage cohorts in this review. Explicit data on comorbidity at a patient level or even just study level is absent from most studies, as only 14 of 36 studies reported this data. In our opinion, the apparent large difference in reported patient comorbidity (10% among one-stage studies versus 50% among two-stage studies) is most likely due to underreporting, not ignoring that a possible genuine lower comorbidity in the one-stage cohort on the other hand may have led to an underestimation of the reinfection risk associated with this procedure. Furthermore, certain types of medication may directly constitute risk factors, including treatment with bisphosphonates.Citation93 However, information on medical treatment of the included study populations is not available. The chosen antibiotic treatment strategy is an area of specific interest regarding reinfection, as the surgical procedure by itself does not resolve the infection. Furthermore, the nature of the infecting microorganism may be a key element regarding outcome. Thus, Gram-negative organisms, multiresistant organisms, and polymicrobial infections have been proposed to predict worse outcomes. As shown in and , this information is not readily available in the existing studies to a degree at which we could adjust for any differences in these and other risk factors in our meta-analysis.

Potential bias

Whether to choose a specific surgical intervention in a non-research, everyday clinical practice environment is determined by many factors. This raises the concern of whether the selection of patients in the individual 36 studies is alike, with consequences for the comparability of the two cohorts in this review. As noted above, a potentially skewed distribution of unreported or unknown confounders may exist. Confounding by indication (surgical bias) could potentially influence the results obtained in this analysis, as surgeons may choose less severely ill patients (eg, with known nonresistant microorganisms) for one-stage revision. By the very nature of two-stage surgery, the surgeon is able to evaluate the progress before reimplantation, this being one of the clinical strengths of this approach compared with one-stage revision. The exclusion in our meta-analysis of patients for whom the second stage was not completed may favor the two-stage approach, since the patients who did not undergo the second stage may constitute a group with poor outcomes. Finally, by limiting our search to English- and German-language studies from only two electronic databases, we may have overlooked studies published in nonindexed journals, or data presented at national or international conferences, which most likely would include more unfavorable results.

Implications for future research

We believe that complications and outcomes (including validated patient-related outcomes measures) of the different revision strategies need more research attention. Recently, the proportion of complications with interim-spacer application has been reported as high as 60%, and fatal complications have also been reported.Citation16,Citation91 Appropriate patient selection seems to be a crucial aspect of success.Citation15,Citation40,Citation94 Given the complexity and relative scarcity of patients with chronically infected HA, randomized clinical trials may prove difficult to perform. The estimates obtained in our analysis suggest that a sample size of more than 3500 infected patients would be needed to investigate superiority of two-stage versus one-stage revision regarding reinfection with statistical precision. Meanwhile, we recommend adoption of standardized reporting of essential data among patients treated for chronically infected HA to ensure the future possibility of performing improved collaborative meta-analysis.Citation21 We thus recommend that future publications on this matter include relevant individual patient information, making it possible to pool data on a patient level, including detailed data on potential risk factors, duration since last surgical procedure, the duration of symptoms, clear information regarding diagnosis of infection, and grade according to the modified McPherson staging system.Citation13

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Kristian Larsen PT, MPH, PhD (†2010) for his help in facilitating the early progress of this study.

Disclosures

Financial support for Jeppe Lange’s salary was received from the Lundbeck Foundation. Jeppe Lange is also principal investigator on the Cementless One-Stage Revision of the Chronic Infected Hip Arthroplasty trial. No other conflict of interest exists for any of the authors.

References

- BozicKJKurtzSMLauEOngKVailTPBerryDJThe epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United StatesJ Bone Joint Surg Am20099112813319122087

- ZhanCKaczmarekRLoyo-BerriosNSanglJBrightRAIncidence and short-term outcomes of primary and revision hip replacement in the United StatesJ Bone Joint Surg Am20078952653317332101

- HooperGJRothwellAGStringerMFramptonCRevision following cemented and uncemented primary total hip replacement: a seven-year analysis from the New Zealand Joint RegistryJ Bone Joint Surg Br20099145145819336803

- KurtzSMLauESchmierJOngKLZhaoKParviziJInfection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United StatesJ Arthroplasty20082398499118534466

- UrquhartDMHannaFSBrennanSLIncidence and risk factors for deep surgical site infection after primary total hip arthroplasty: a systematic reviewJ Arthroplasty2010251216122219879720

- KurtzSOngKLauEMowatFHalpernMProjections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030J Bone Joint Surg Am20078978078517403800

- KurtzSMLauEOngKZhaoKKellyMBozicKJFuture young patient demand for primary and revision joint replacement: national projections from 2010 to 2030Clin Orthop Relat Res20094672606261219360453

- Del PozoJLPatelRClinical practice. Infection associated with prosthetic jointsN Engl J Med200936178779419692690

- ZimmerliWTrampuzAOchsnerPEProsthetic-joint infectionsN Engl J Med20043511645165415483283

- CrockarellJRHanssenADOsmonDRMorreyBFTreatment of infection with debridement and retention of the components following hip arthroplastyJ Bone Joint Surg Am199880130613139759815

- TsukayamaDTEstradaRGustiloRBInfection after total hip arthroplasty. A study of the treatment of one hundred and six infectionsJ Bone Joint Surg Am1996785125238609130

- TheisJCImplant retention in infected joint replacements: a surgeon’s perspectiveInt J Artif Organs20083180480918924092

- HanssenADOsmonDREvaluation of a staging system for infected hip arthroplastyClin Orthop Relat Res2002403162212360002

- FinkBRevision of late periprosthetic infections of total hip endoprostheses: pros and cons of different conceptsInt J Med Sci2009628729519834595

- WinklerHRationale for one stage exchange of infected hip replacement using uncemented implants and antibiotic impregnated bone graftInt J Med Sci2009624725219834590

- CabritaHBCrociATCamargoOPLimaALProspective study of the treatment of infected hip arthroplasties with or without the use of an antibiotic-loaded cement spacerClinics (Sao Paulo)2007629910817505692

- BuchholzHWElsonRAEngelbrechtELodenkamperHRottgerJSiegelAManagement of deep infection of total hip replacementJ Bone Joint Surg Br.198163-B3423537021561

- JacksonWOSchmalzriedTPLimited role of direct exchange arthroplasty in the treatment of infected total hip replacementsClin Orthop Relat Res200038110110511127645

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementJ Clin Epidemiol2009621006101219631508

- LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJThe PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaborationJ Clin Epidemiol200962e1e3419631507

- AltmanDGSystematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variablesBMJ200132322422811473921

- BorensteinMHedgesLVHigginsJPTRothsteinHRIntroduction to Meta-AnalysisChichester, UKWiley2009

- EggerMDaveySGSchneiderMMinderCBias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical testBMJ19973156296349310563

- LinJYangXBostromMPTwo-stage exchange hip arthroplasty for deep infectionJ Chemother200113Spec 1546511936381

- CiernyGDiPasqualeDTreatment of chronic infectionJ Am Acad Orthop Surg200614S105S11017003180

- AnagnostakosKSchmidNVKelmJGrunUJungJClassification of hip joint infectionsInt J Med Sci2009622723319841729

- CuiQMihalkoWMShieldsJSRiesMSalehKJAntibiotic-impregnated cement spacers for the treatment of infection associated with total hip or knee arthroplastyJ Bone Joint Surg Am20078987188217403814

- MoyadTFThornhillTEstokDEvaluation and management of the infected total hip and kneeOrthopedics20083158158818661881

- SalvatiEAGonzález Della ValleAMasriBADuncanCPThe infected total hip arthroplastyInstr Course Lect20035222324512690851

- MitchellPAMasriBAGarbuzDSGreidanusNVDuncanCPCementless revision for infection following total hip arthroplastyInstr Course Lect20035232333012690860

- HaddadFSMasriBAGarbuzDSDuncanCPThe treatment of the infected hip replacement. The complex caseClin Orthop Relat Res199914415610611869

- SukeikMHaddadFSTwo-stage procedure in the treatment of late chronic hip infections – spacer implantationInt J Med Sci2009625325719834591

- FrieseckeCWodtkeJManagement of periprosthetic infectionChirurg200879777792 German18584136

- DuncanCPMasriBAThe role of antibiotic-loaded cement in the treatment of an infection after a hip replacementInstr Course Lect1995443053137797868

- HanssenADRandJAEvaluation and treatment of infection at the site of a total hip or knee arthroplastyInstr Course Lect19994811112210098033

- GarvinKLHanssenADInfection after total hip arthroplasty. Past, present, and futureJ Bone Joint Surg Am199577157615887593069

- HanssenADSpangehlMJTreatment of the infected hip replacementClin Orthop Relat Res2004420637115057080

- KaltsasDSInfection after total hip arthroplastyAnn R Coll Surg Engl20048626727115239869

- BernardLHoffmeyerPAssalMVaudauxPSchrenzelJLewDTrends in the treatment of orthopaedic prosthetic infectionsJ Antimicrob Chemother20045312712914688050

- LanglaisFCan we improve the results of revision arthroplasty for infected total hip replacement?J Bone Joint Surg Br20038563764012892181

- LehnerBWitteDSudaAJWeissSRevision strategy for periprosthetic infectionOrthopade200938681688 German19657619

- MatthewsPCBerendtARMcNallyMAByrenIDiagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infectionBMJ2009338b177319482869

- RuchholtzSTagerGNast-KolbDThe infected hip prosthesisUnfallchirurg2004107307317 German15188776

- MaderazoEGJudsonSPasternakHLate infections of total joint prostheses. A review and recommendations for preventionClin Orthop Relat Res19882291311423280197

- TomsADDavidsonDMasriBADuncanCPThe management of peri-prosthetic infection in total joint arthroplastyJ Bone Joint Surg Br20068814915516434514

- MastersonELMasriBADuncanCPTreatment of infection at the site of total hip replacementInstr Course Lect1998472973069571431

- YooJJKwonYSKooKHYoonKSKimYMKimHJOne-stage cementless revision arthroplasty for infected hip replacementsInt Orthop2009331195120118704412

- LaiKAYangCYLinRMJouIMLinCJCementless reimplantation of hydroxyapatite-coated total hips after periprosthetic infectionsJ Formos Med Assoc1996954524578772051

- RudelliSUipDHondaELimaALOne-stage revision of infected total hip arthroplasty with bone graftJ Arthroplasty2008231165117718534510

- MulcahyDMO’ByrneJMFenelonGEOne stage surgical management of deep infection of total hip arthroplastyIr J Med Sci199616517198867490

- CallaghanJJKatzRPJohnstonRCOne-stage revision surgery of the infected hip. A minimum 10-year followup studyClin Orthop Relat Res199936913914310611868

- HopePGKristinssonKGNormanPElsonRADeep infection of cemented total hip arthroplasties caused by coagulase-negative staphylococciJ Bone Joint Surg Br1989718518552584258

- UreKJAmstutzHCNasserSSchmalzriedTPDirect-exchange arthroplasty for the treatment of infection after total hip replacement. An average ten-year follow-upJ Bone Joint Surg Am1998809619689698000

- RautVVSineyPDWroblewskiBMOne-stage revision of total hip arthroplasty for deep infection. Long-term followupClin Orthop Relat Res19952022077497670

- DrancourtMSteinAArgensonJNZannierACurvaleGRaoultDOral rifampin plus ofloxacin for treatment of Staphylococcus-infected orthopedic implantsAntimicrob Agents Chemother199337121412188328772

- ButtaroMAPussoRPiccalugaFVancomycin-supplemented impacted bone allografts in infected hip arthroplasty. Two-stage revision resultsJ Bone Joint Surg Br20058731431915773637

- FehringTKCaltonTFGriffinWLCementless fixation in 2-stage reimplantation for periprosthetic sepsisJ Arthroplasty19991417518110065723

- FinkBGrossmannAFuerstMSchaferPFrommeltLTwo-stage cementless revision of infected hip endoprosthesesClin Orthop Relat Res20094671848185819002539

- HofmannAAGoldbergTDTannerAMCookTMTen-year experience using an articulating antibiotic cement hip spacer for the treatment of chronically infected total hipJ Arthroplasty20052087487916230238

- KooKHYangJWChoSHImpregnation of vancomycin, gentamicin, and cefotaxime in a cement spacer for two-stage cementless reconstruction in infected total hip arthroplastyJ Arthroplasty20011688289211607905

- YamamotoKMiyagawaNMasaokaTKatoriYShishidoTImakiireAClinical effectiveness of antibiotic-impregnated cement spacers for the treatment of infected implants of the hip jointJ Orthop Sci2003882382814648272

- NestorBJHanssenADFerrer-GonzalezRFitzgeraldRHThe use of porous prostheses in delayed reconstruction of total hip replacements that have failed because of infectionJ Bone Joint Surg Am1994763493598126040

- McDonaldDJFitzgeraldRHIlstrupDMTwo-stage reconstruction of a total hip arthroplasty because of infectionJ Bone Joint Surg Am1989718288342745478

- Cordero-AmpueroJEstebanJGarcia-CimbreloEOral antibiotics are effective for highly resistant hip arthroplasty infectionsClin Orthop Relat Res20094672335234219333670

- EvansRPSuccessful treatment of total hip and knee infection with articulating antibiotic components: a modified treatment methodClin Orthop Relat Res2004427374615552134

- MagnanBRegisDBiscagliaRBartolozziPPreformed acrylic bone cement spacer loaded with antibiotics: use of two-stage procedure in 10 patients because of infected hips after total replacementActa Orthop Scand20017259159411817873

- DairakuKTakagiMKawajiHSasakiKIshiiMOginoTAntibiotics-impregnated cement spacers in the first step of two-stage revision for infected totally replaced hip joints: report of ten trial casesJ Orthop Sci20091470471019997816

- NusemIMorganDAStructural allografts for bone stock reconstruction in two-stage revision for infected total hip arthroplasty: good outcome in 16 of 18 patients followed for 5–14 yearsActa Orthop200677929716534707

- LiebermanJRCallawayGHSalvatiEAPellicciPMBrauseBDTreatment of the infected total hip arthroplasty with a two-stage reimplantation protocolClin Orthop Relat Res19943012052128156676

- Sanchez-SoteloJBerryDJHanssenADCabanelaMEMidterm to long-term followup of staged reimplantation for infected hip arthroplastyClin Orthop Relat Res200946721922418813895

- StockleyIMockfordBJHoad-ReddickANormanPThe use of two-stage exchange arthroplasty with depot antibiotics in the absence of long-term antibiotic therapy in infected total hip replacementJ Bone Joint Surg Br20089014514818256078

- IncavoSJRussellRDMathisKBAdamsHInitial results of managing severe bone loss in infected total joint arthroplasty using customized articulating spacersJ Arthroplasty20092460761318617360

- LimSJParkJCMoonYWParkYSTreatment of periprosthetic hip infection caused by resistant microorganisms using 2-stage reimplantation protocolJ Arthroplasty2009241264126919523784

- WangJWChenCEReimplantation of infected hip arthroplasties using bone allograftsClin Orthop Relat Res19972022109020219

- WhittakerJPWarrenREJonesRSGregsonPAIs prolonged systemic antibiotic treatment essential in two-stage revision hip replacement for chronic Gram-positive infection?J Bone Joint Surg Br200991445119092003

- ScharfenbergerAClarkMLavoieGO’ConnorGMassonEBeaupreLATreatment of an infected total hip replacement with the PROSTALAC system. Part 1: Infection resolutionCan J Surg200750242817391612

- WalterGBuhlerMHoffmannRTwo-stage procedure to exchange septic total hip arthroplasties with late periprosthetic infection. Early results after implantation of a reverse modular hybrid endoprosthesisUnfallchirurg2007110537546 German17361449

- TakigamiIItoYIshimaruDTwo-stage revision surgery for hip prosthesis infection using antibiotic-loaded porous hydroxyapatite blocksArch Orthop Trauma Surg20101301221122619876636

- IsiklarZUDemirorsHAkpinarSTandoganRNAlparslanMTwo-stage treatment of chronic staphylococcal orthopaedic implant-related infections using vancomycin impregnated PMMA spacer and rifampin containing antibiotic protocolBull Hosp Jt Dis199958798510509199

- ScharfenbergerAClarkMLavoieGO’ConnorGMassonEBeaupreLATreatment of an infected total hip replacement with the PROSTALAC system. Part 2: Health-related quality of life and function with the PROSTALAC implant in situCan J Surg200750293317391613

- LangJMRothmanKJCannCIThat confounded P-valueEpidemiology19989789430261

- KammeCLindbergLAerobic and anaerobic bacteria in deep infections after total hip arthroplasty: differential diagnosis between infectious and non-infectious looseningClin Orthop Relat Res19811542012077009009

- AtkinsBLAthanasouNDeeksJJProspective evaluation of criteria for microbiological diagnosis of prosthetic-joint infection at revision arthroplasty. The OSIRIS Collaborative Study GroupJ Clin Microbiol199836293229399738046

- FitzgeraldRHNolanDRIlstrupDMVan ScoyREWashingtonJACoventryMBDeep wound sepsis following total hip arthroplastyJ Bone Joint Surg Am197759847855908714

- CiernyGDiPasqualeDPeriprosthetic total joint infections: staging, treatment, and outcomesClin Orthop Relat Res2002403232812360003

- CoventryMBTreatment of infections occurring in total hip surgeryOrthop Clin North Am1975699110031178168

- Della ValleCJZuckermanJDDi CesarePEPeriprosthetic sepsisClin Orthop Relat Res2004420263115057075

- McPhersonEJWoodsonCHoltomPRoidisNShufeltCPatzakisMPeriprosthetic total hip infection: outcomes using a staging systemClin Orthop Relat Res200240381512360001

- McPhersonEJTontzWJrPatzakisMOutcome of infected total knee utilizing a staging system for prosthetic joint infectionAm J Orthop19992816116510195839

- OussedikSIHaddadFSThe use of linezolid in the treatment of infected total joint arthroplastyJ Arthroplasty20082327327818280424

- JungJSchmidNVKelmJSchmittEAnagnostakosKComplications after spacer implantation in the treatment of hip joint infectionsInt J Med Sci2009626527319834592

- PedersenABSvendssonJEJohnsenSPRiisAOvergaardSRisk factors for revision due to infection after primary total hip arthroplasty. A population-based study of 80,756 primary procedures in the Danish Hip Arthroplasty RegistryActa Orthop20108154254720860453

- ThillemannTMPedersenABMehnertFJohnsenSPSoballeKPostoperative use of bisphosphonates and risk of revision after primary total hip arthroplasty: a nationwide population-based studyBone20104694695120102756

- ParviziJGhanemEAzzamKDavisEJaberiFHozackWPeriprosthetic infection: are current treatment strategies adequate?Acta Orthop Belg20087479380019205327