Abstract

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are disorders of chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract marked by episodes of relapse and remission. Over the past several decades, advances have been made in understanding the epidemiology of IBD. The incidence and prevalence of both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis have been increasing worldwide across pediatric and adult populations. As IBD is thought to be related to a combination of individual genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers, and alterations in the gut microbiome that stimulate an inflammatory response, understanding the potentially modifiable environmental risk factors associated with the development or the course of IBD could impact disease rates or management in the future. Current hypotheses as to the development of IBD are reviewed, as are a host of environmental cofactors that have been investigated as both protective and inciting factors for IBD onset. Such environmental factors include breast feeding, gastrointestinal infections, urban versus rural lifestyle, medication exposures, stress, smoking, and diet. The role of these factors in disease course is also reviewed. Looking forward, there is still much to be learned about the etiology of IBD and how specific environmental exposures intimately impact the development of disease and also the potential for relapse.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract marked by episodes of relapse and remission. There are two identified subtypes of the disease, ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s Disease (CD), which differ in patterns of involvement. Though varying in clinical presentation, the two subtypes share a presumed etiology of genetic predisposition, environmental risk factors or exposures, and alterations of the gut microbiome that contributes to the manifestation of disease. Ongoing changes in environmental factors, including infections, diet, lifestyle factors, and medication use have contributed to shifts in the global prevalence of the disease.

Epidemiology of IBD

Currently, the annual incidence of CD is highest in North America (20.2 per 100,000, per person years); whereas the annual incidence of UC is highest in Europe (24.3 per 100,000 per person years). The prevalence of both UC and CD are highest in Europe (505 and 322, per 100,000 per person years respectively).Citation1 A much lower prevalence is found in other areas of the world.Citation1 However, IBD appears to be emerging in such areas as the People’s Republic of China, South Korea, India, Lebanon, Iran, Thailand, the French West Indies, and North Africa, correlating with industrialization and westernization of these areas.Citation2 Prevalence of IBD is affected by both incidence (new diagnoses) and duration of disease. As IBD is a chronic disabling disorder without high mortality, prevalence rates may now be increasing due to earlier diagnoses and potentially to longer duration of disease. The more recent findings in geographic trends of IBD may argue against the previously observed north–south gradient described in Europe, the US, Scotland, and France. For example, there are now higher incidence rates of IBD in countries such as AustraliaCitation3 and New Zealand.Citation4 The incidence of IBD has continued to rise in other prior low incidence areas, such as Asia and the developing world. As IBD emerges in developing countries, UC appears first, followed by a rising trend in CD is observed.Citation5 This pattern is being seen currently in Asia.Citation6 These data support the argument that lifestyle and environmental factors are important cofactors in the etiology of IBD. Importantly, there are only limited data on the epidemiology of IBD to date in under developed countries. More accurate means of determining incidence and prevalence in these areas are needed.

Pediatric IBD demonstrates a different pattern, with CD predominating over UC. In a recent population based study from Sweden, the incidence of CD was estimated to be (95% confidence interval [CI] 7.5–11.2) per 100,000 per person years. The incidence of UC in children over the same time period was 2.8 (95% CI 1.9–4.0) per 100,000 per person years.Citation7 These rates are somewhat higher than those reported in other pediatric studies, although similar to those reported in modern studies from Canada,Citation3,Citation8,Citation9 Norway,Citation10 and Finland.Citation11 In a recent systematic review of international trends in pediatric IBD incidence, over 60% of studies reported a rising incidence of CD and 20% reported a rising incidence of UC. This increasing incidence occurred in both developed and developing nations; however, admittedly, most countries lacked accurate estimates.Citation3

Interestingly, geographic location plays a convincing role in IBD development. For example, studies of emigrants have demonstrated that migration from a lower prevalence area of IBD to a higher prevalence area increases a person’s associated risk. In a study of children who migrated from South Asia to British Columbia (BC), migrants had an even higher incidence of IBD than the rest of the BC pediatric population.Citation12 Additionally, there was a different pattern of phenotypic expression, male predominance, and more extensive colonic disease among immigrants. This suggests a potential effect of migration, and environmental and lifestyle changes not only on IBD development, but potentially on phenotype and course of disease. In a separate study of Indian emigrants who moved to Leicestershire, incidence rates of UC were comparable to those in their new environment.Citation13 Among those emigrating from low to high prevalence countries, first generation children seem to be at a higher risk for IBD in their new environments. Age at time of migration also appears to be important, as those raised in the adoptive country or those who migrated during childhood have the greatest risk of developing IBD.Citation5 This pattern of increased risk associated with emigration has been replicated in other nationalities as well. For example, in a study of emigrants from Spain to other countries, there was an increased risk of IBD with emigration to westernized European countries (odds ratio [OR] 1.91, 95% CI 1.07–3.47), but not to Latin America (OR 1.48, 95% CI 0.67–3.27).Citation14 Certainly, the increased rates of IBD development in emigrants provide etiologic clues as to the important environmental cofactors necessary for disease occurrence.

Little difference has been found in rates of IBD with gender, with relatively equal gender distributions across multiple studies. However, in a study of patients in Ontario from 1994 to 2005, a predominance of male patients with CD was identified in younger age groups (5–9 years and 10–14 years), but the incidence was balanced between males and females by 15–17 years of age.Citation15 With regards to age, the incidence of IBD has been found to be the highest between the second and fourth decade of life, with a median age of onset slightly higher for UC when compared to CD. Earlier studiesCitation16–Citation22 show a bimodal distribution of IBD incidence, with the highest incidence between ages 20 to 39 years, and another peak occurring at age 60. This second peak has not been replicated in a more recent study.Citation23 In areas of emerging incidence of IBD, such as Asia, there is a male predominance for CD, but a more equal gender distribution for UC. The age of diagnosis in Asia is slightly higher than that in European countries and there is rarely a second incidence peak.Citation6

Genetic–environment interactions

Genetics

Recently, there has been a great increase in the understanding of the genetic component of IBD etiology. Genome wide association studies have identified over 160 susceptibility loci/genes that are significantly associated with IBD.Citation24,Citation25 For CD, gene discoveries have focused on defective processing of intracellular bacteria, autophagy, and innate immunity. For UC, the focus has been on barrier function. There is also a suggestion of overlap of some susceptibility loci with other immune related diseases.Citation25 In a study published in 2003 that focused on familial aggregation of IBD, the concordance level was only 50% for CD and 19% for UC in monozygotic twins.Citation26,Citation27 This provides evidence that more than genetics is needed for IBD development. Interestingly, in a recent extension of the Swedish twin registryCitation28 with extended observation time, an even lesser rate of pair concordance was found for monozygotic twins (27% for CD and 15% for UC).Citation28 By comparing concordant and discordant twin pairs with CD, the authors found a trend for phenotypic differences, suggesting that pathophysiological differences may be associated with separate phenotypes of CD.Citation28 Sharing a living environment increases the incidence of IBD, as seen in new diagnoses of IBD in family members and spouses of individuals with IBD sharing living space.Citation29,Citation30 Birth order also influences disease status. As adjacent order of birth estimates environmental sharing, this suggests that environmental factors contribute to the observed familial aggregations of IBD.Citation22 Differences between CD and UC are thought to be not only due to genetic predisposition, but also be partially due to the impact of environmental exposures and triggers subsequently affecting the host’s immunity.

Gastrointestinal microbiota

The enteric microbiota are now accepted as a central etiologic factor in the pathogenesis of IBD.Citation25,Citation31 It is thought that the first year of life is a critical time period for development of an individual’s microbiome and potentially helps to establish whether maintenance of homeostasis versus development of inflammation will occur. Importantly, bacteria mediated epigenetic effects on the mucosal immune system in early life have been shown to affect the development of immunologically mediated disease in adulthood.Citation32 Recent changes in technology have allowed for a greater understanding of the composition and community structure of the intestinal microbiota. Researchers have determined how enteric bacterial species and their metabolic products interact within the host. Immunologic properties of individual species and groups of bacteria have been described.Citation33,Citation34 Specific viral or bacterial commensal microbes appear to selectively interact with host genes to influence intestinal inflammation. Epidemiology has aided in the discovery of the microbiome as an important factor in IBD development, as studies of early life antibiotic exposure (which alters the intestinal microbiome) have shown increased risk for development of CD later in life.Citation35

Hygiene hypothesis of IBD development

A key principle to understanding the genetic–environmental interactions associated with IBD development is the hygiene hypothesis. In essence, this hypothesis proposes that “cleaner” environments with lower rates of communicable diseases are associated with increased rates of IBD development, and that the converse is also true, less hygienic environments play a protective role. Protective factors that have been proposed under this hypothesis include lower rates of antibiotic use, increased numbers of pets and livestock, larger family sizes, and increased exposure to enteric pathogens (specifically Helicobacter pylori [H. pylori] and helminths).Citation36 There is an increased risk of IBD development in countries with lower rates of enteric pathogens and where there is greater access to hot water and other sanitization resources. In general, in developing countries, where there are more infectious exposures in childhood, there are lower rates of allergic disorders. Not all studies have been consistent in whether these “hygiene factors” are associated with IBD development.Citation37 Some of these differences may be related to the retrospective nature of prior case control studies, and potential for biases in recall and how controls are selected. Only a further understanding of how each environmental exposure is associated with IBD development will impact occurrence of IBD in the future.

Environmental exposures and IBD

Breast feeding

There is conflict as to whether breast feeding increases the risk, or encompasses a protective role, for the development of IBD by alteration of the gut microbiota of breast fed infants. In a population based case control study of 222 incident cases of CD occurring prior to age 17, breast feeding was a significant risk factor for CD (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.3–3.4).Citation38 A meta-analysis of 14 case control studies found that breast feeding had a protective effect on the development of UC (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.44–0.84), but not on CD.Citation39 A second systematic review and meta-analysis published in also found a significant protective effect (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.51–0.94) for the development of early onset IBD overall.Citation40 However, the findings did not reach statistical significance for CD and UC separately.Citation40 Another study has shown no effect of breast feeding on IBD development.Citation41 Interestingly, there may be a dose-response effect for breast feeding, with a recent case control study demonstrating a protective effect only after a duration of 3 months or more.Citation42 A separate recent study found a nonsignificant protective effect (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.23–1.11) for a breast feeding duration of >6 months.Citation43 This may be one factor contributing to the conflicting data in the literature, as some studies did not take duration of breast feeding into account. Limitations to prior studies include the potential for recall bias and that studies primarily utilized retrospective data collection. The potential mechanism of action of breast feeding impacting development of IBD is thought to be related to changes in the gut fora of breast fed infants. In breast fed infants, there are higher concentrations of bifidobacteria and fewer anaerobic bacteria in feces when compared to bottle fed infants.Citation44 It is thought that fecal fora can continue to change up until 2 years of age, demonstrating the potential need for a longer duration of breast feeding to impact a child’s risk of IBD development.Citation45

Infectious exposures

Several infectious agents have been suspected to affect the development of IBD, whether in a protective or inciting role, including causes of acute bacterial gastroenteritis, H. pylori, and helminth exposure. These infectious factors may alter the gut microbiota or may have a specific immunomodulatory role in development of IBD.

Bacterial gastroenteritis

In a population based study from two Danish counties comparing persons exposed to salmonella and Campylobacter gastroenteritis identified in lab registries to matched unexposed individuals, the hazard ratio (HR) of first time diagnosis of IBD of those who were exposed compared to those who were unexposed was 2.9 (95% CI 2.2–3.9) for the whole 7.5 year observation period and 1.9 (95% CI 1.4–2.6) for the first year, after exposure was excluded.Citation46 In a separate study in the military population, a prior episode of infectious gastroenteritis was associated with an increased risk of IBD, even after excluding episodes in the 6 months prior to IBD diagnosis (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.19–1.66).Citation47 It is understood, however, that those with IBD are more likely to undergo hospitalizations and diagnostic testing which may isolate bacterial infections more frequently than in the population without IBD. Additionally, the risks associated with a bacterial gastroenteritis may also be influenced by antibiotics that were prescribed for treatment of the infection. Alterations in the gut microbiota that occur may be related to the antibiotic, which can then be attributed to the prior bacterial infection.

H. pylori

H. pylori has also been implicated in the development of autoimmune diseases including multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, asthma, and IBD.Citation48,Citation49H. pylori is a common chronic bacterial infection in humans that is often acquired in childhood in less developed countries. Chronic colonization with H. pylori may also be associated with social class and other protective factors involved in the hygiene hypothesis. In a meta-analysis of 23 studies, H. pylori infection was inversely associated with IBD, more so for CD than for UC.Citation48 Overall, 27.1% of IBD patients had evidence of prior infection with H. pylori in comparison to 40.9% of patients in the control group. The meta-analysis described a number of important flaws in the literature which caused difficulty in aggregating the individual study findings. For example, there was evidence of publication bias, heterogeneity among studies, and differing modalities for diagnosis of H. pylori infection. In a recent study using surgical pathology reports, the presence of H. pylori was inversely associated with IBD, with an adjusted OR of 0.48 (95% CI 0.27–0.79) for CD and an adjusted OR of 0.59 (95% CI 0.39–0.84) for UC.Citation50 Experimentally, researchers have shown that the H. pylori genome has immunoregulatory properties and can downregulate inflammatory responses through interaction with mucosal dendritic cells.Citation51 While H. pylori may play an as of yet undefined role in the development of IBD, there are no data on the role of H. pylori in improving or exacerbating disease activity.

Helminths

Helminths are complex multicellular organisms that have the ability to induce immune host regulatory cells that suppress inflammation.Citation52 Helminths have, therefore, been investigated as having a potentially protective effect in IBD development due to the aforementioned geographical differences in IBD incidence, with prevalence of IBD inversely related to helminth burden. Helminths are divided into three main groups: nematodes (round worms), trematodes (flukes), and cestodes (tape worms). Each group may have a distinct effect on immune modulation, and potentially on development or treatment of immune mediated disorders.Citation52 Helminths are also thought to have an immunoregulatory role within the intestinal flora.Citation53 In a recent case control study from South Africa, childhood exposure to helminths was protective against both CD and UC development (adjusted OR of 0.2 [95% CI 0.1–0.4] for CD and adjusted OR of 0.2 [95% CI 0.1–0.6] for UC).Citation54 Experimental data on helminths have also shown a protective effect on IBD development. In animal models of IBD, helminth colonization suppresses intestinal inflammation through multiple mechanisms including induction of innate and adaptive regulatory circuits.Citation55,Citation56 For example, in murine models of IBD, the helminth Heligmosomoides polygyrus bakeri prevents colitis by altering dendritic cell function.Citation55 Interestingly, helminth exposure has also been shown to shift the composition of intestinal bacteria,Citation56 which may then impact disease development or course. When Trichuris suis (T. suis), a whipworm, was used in a small open label study of CD, patients showed improvement in their disease activity and quality of life scores.Citation57 Patients with UC also experienced beneficial effects of oral T. suis administration in a small randomized controlled trial.Citation58 Whipworms are potentially a good candidate for clinical use as they do not migrate beyond the intestines or multiply within their host. They are also not transmitted from one human to another. Further trials of helminths in the treatment of both CD and UC are ongoing.

Medications

Antibiotics

Early and recurrent exposure to antibiotics has been associated with an increased risk of developing IBD. Published 2012, a retrospective cohort study of children 2 years of age or older from the UK compared the incidence rate of IBD in those who were and were not exposed to antianaerobic antibiotics.Citation59 The incidence rate of IBD was higher in those exposed to antibiotics when compared to those who were not, where the incidence was 0.83 and 1.52 per 10,000 person years, respectively, for an 84% relative risk increase. Time of antibiotic exposure was also important, although exposure to antibiotics throughout childhood was associated with developing IBD, the relationship decreased with increasing age at exposure. Lastly, a dose-response effect existed, with receipt of more than two antibiotic courses being more highly associated with IBD development than receipt of one to two courses, with adjusted HR of 4.77 (95% CI 2.13–10.68) versus 3.33 (95% CI 1.69–6.58), respectively.Citation59 In a nested case control study in Canada, antibiotic use within the first year of life was also associated with a significantly increased risk (almost three fold) of developing IBD, with a stronger risk for CD.Citation60 A separate case control study in Finland found an increased risk of pediatric CD associated with early antibiotic use, even with exclusion of prescriptions in the 6 months prior to diagnosis (OR 3.48, 95% CI 1.57–7.34).Citation61 There was no increased risk of UC associated with antibiotic use in this study.Citation61 Use of antibiotics may therefore be associated with disease development through a mechanism of alteration of the gut microbiome, or alternatively, patients with a genetic susceptibility to IBD may have increased susceptibility to childhood infections, thereby requiring more frequent antibiotic dosing. Interestingly, adults with newly diagnosed IBD are also more likely to have taken antibiotics in the 5 years prior to IBD diagnosis. There was a dose-dependent relationship between the number of antibiotic dispensations and the risk of IBD in an adult Canadian population.Citation62 Whether there is a direct pathologic effect of antibiotics alone or in association with an immune response, those with greater access to antibiotics appear more likely to develop IBD.

Oral Contraceptive Agents (OCPs)

OCPs are a commonly used method to prevent pregnancy and is a common exposure for women of child bearing age. There has been much debate as to whether OCPs increase the incidence of IBD or lead to more frequent relapses in those already diagnosed. Following the trend of findings observed in previous studies, in a reviewCitation63 of two large prospective cohorts of US women published in 2012, OCP use was associated with a modest risk of CD more so than UC. Specifically, when compared with never users of OCPs, the HR for CD was 2.82 (95% CI 1.65–8.84) among currents users and 1.39 (95% CI 1.05–1.85) among past users.Citation63 Furthermore, it was found that the association between OCP use and UC was limited to women with a history of smoking, which suggests a multifaceted rather than isolated influence of estrogen and subsequent disease development. In a meta-analysis published in 2008 from the UK, a modest positive association for development of CD and UC with OCP use after controlling for smoking (pooled relative risk [RR] 1.46 for CD and 1.28 for UC) was found.Citation64 Additionally, the risk for patients who stopped OCPs reverted back to that of the unexposed population.Citation64 The proposed mechanism of action behind OCP use and development of IBD is thought to be related to estrogen-based immune enhancement and proliferation of macrophages, or possibly due to promotion of microvascular bowel ischemia and thrombosis.Citation64 One prior study has shown an increased risk of relapse among patients with CD on OCPs (HR 3.0, 95% CI 1.5–5.9), although it is unclear whether higher doses of estrogen may be involved in this risk, as data were from the 1990s in this study.Citation65 A second study during the same time period showed no increase in risk of relapse in patients with CD on OCPs.Citation66 Therefore, although evidence is limited, OCPs are not definitively associated with a significant risk of relapse of IBD in individuals with established disease.Citation67

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs are thought to influence IBD development via direct damage to the mucosa of the bowel or through reduction in prostaglandin production.Citation68 NSAIDs have been associated with an increased risk for both CD and UC. In 2012, a prospective cohort studyCitation69 of women in the US revealed that frequent use of NSAIDs, but not aspirin, was associated with an increased absolute incidence of CD and UC. Specifically, when compared with nonusers, women who used NSAIDs at least 15 days per month had an increased risk for both CD and UC (absolute difference in age adjusted incidence of six cases per 100,000 person years [HR 1.59, 95% CI 0.99–2.56] for CD and an absolute difference of seven cases per 100,000 person years [HR 1.87, 95%CI 1.16–2.99] for UC).Citation69 The same risk was not found with specific use of aspirin in this study. In a separate trial investigating the potential for relapse among individuals with established IBD, NSAID ingestion was associated with frequent and early clinical relapse. Within 9 days of ingestion, 17%–28% of patients on NSAID therapy relapsed.Citation70 In this short-term study, selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 was well tolerated without risk of relapse. In contrast, another study has not found NSAIDs to be associated with fares of established disease.Citation71 More prospective data are needed on the role of NSAIDs in disease development and exacerbation.

Vitamin D

The role of vitamin D in IBD development and exacerbation is emerging. Patients with both previously diagnosed and new onset IBD have been found to be vitamin D deficient. This deficiency is thought to be related to reduced physical activity, reduced sunlight exposure, malnutrition, inadequate dietary intake, or lower bioavailability. It is also possible that vitamin D affects the immune system through T cells, B cells, and antigen-presenting cells, impacting disease development and/or course.Citation72 A study from a large prospective cohort of female nurses initiated in 1976 and 1989, respectively, revealed that women living in southern latitudes had a lower risk of CD (HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.30–077) and UC (HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.42–0.90) when compared to those residing in northern latitudes.Citation73 This trend, consistent with the north–south gradient of disease that has been seen historically in the US and Europe, has been hypothesized to correlate with ultraviolet light exposure and ultimately vitamin D levels. In another study from this cohort, higher predicted plasma levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) significantly reduced the risk for incident CD but did not significantly reduce the risk for UC in women.Citation74 Specifically, women with a 25(OH)D level greater than 30 ng/mL had a significantly reduced risk of CD when compared to women with a predicted 25(OH) D level less than 20 ng/mL (HR 0.38, 95% CI 0.15–0.97), and a nonsignificant decreased risk of UC (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.19–1.70). In a separate study evaluating the impact of vitamin D level on disease course, vitamin D deficiency was associated with lower health related quality of life and increased disease activity in CD.Citation75

Lifestyle exposures

Socioeconomic factors

Living in an urban setting has been associated with an increased risk for IBD through a series of studies conducted in the last six decades. In a systematic review published in 2012, living in an urban setting was associated with an increased risk of both UC and CD (pooled Incidence rate ratio (IRR) 1.17 [95% CI 1.03–1.32] for UC and pooled IRR 1.42 [95% CI 1.26–1.60] for CD).Citation76 In a Norwegian study, the incidence of IBD was higher in rural areas with a recent increase in socioeconomic status, when compared to urban areas with a stable high socioeconomic level.Citation77 Several factors may be involved in these increased risks, including population density, education, lifestyle changes, and potentially, exposure to industrial agents. For example, in a database study of residents in the UK, it was found that ambient air pollution was not associated with IBD, but exposure to SO2 and NO2 may increase the risk of early onset UC and CD, respectively.Citation78 In an ecological study, total air emissions of criteria pollutants were also significantly correlated with hospitalizations for adults with IBD.Citation79 While causality cannot be concluded from a ecological study, these data lend support to the hypothesis that components of industrialization, such as pollution, may play a role in the development and course of IBD. In a study of German employees, factors such as working in the open air and physical exercise were protective against the development of IBD, while being exposed to artificial working conditions, including climate control mechanisms such as air conditioning, or extending and irregular shift working, increased the risk of IBD.Citation80 These findings further argue that factors associated with an urban lifestyle influence one’s risk of IBD. It is unclear whether the relationship occurs due to the environment itself or in combination with one’s genetic predisposition to the disease.

Smoking

Smoking is the most widely and longest studied environmental exposure associated with IBD. To date, it has been observed that smoking has a varying impact on CD and UC, contributing to an increased risk for individuals with CD and a protective role in individuals with UC. In an early meta-analysis, current smoking (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.65–2.47) was shown to increase the risk for CD, but paradoxically decreased the risk for UC (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.34–0.48).Citation81 A more recent meta-analysis, using quality standards for meta-analysis reporting, found similar effects, with an increased risk for CD associated with current smoking (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.40–2.22) and an increased risk for UC with former smoking (OR 1.79, 95% CI 1.37–2.34). Current smoking served a protective role in the development of UC (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.45–0.75).Citation82 This protective role of smoking in UC remains until 2–5 years after cessation, after which increased risk develops. This risk may remain elevated for up to 20 years.Citation83 The pathophysiology associated with the paradoxical effects of smoking on CD and UC is not well understood, but it is hypothesized that there are influences from nicotine and oxidative stress.Citation84 Not only does smoking have an impact on the incidence of IBD, it also influences disease course by inciting relapses among those with CD. In a prospective cohort studyCitation85 published in 1999, the adjusted RR for disease relapse among current smokers with CD was 1.35 (95% CI 1.03–1.76). This risk was increased in patients with previously inactive disease and in those who had no colonic lesions. The increased risk of disease relapse has became significant above a threshold of 15 cigarettes per day. In this study, former smokers behaved like nonsmokers and were noted not to have the observed increased risk. Additionally, smoking is associated with an increased risk of disease recurrence after surgery in CD.Citation85,Citation86 Interestingly, the studies on smoking are not necessarily consistent across all ethnic groups, demonstrating the potential for interaction between smoking and other environmental or genetic factors to influence disease occurrence, course, or phenotype.Citation2,Citation87

Diet

As a large and variable environmental exposure, dietary factors may serve as risk or protective factors on IBD development. There are several proposed mechanisms of action for the visualized associations between IBD and dietary choices. These proposed mechanisms include a direct effect of dietary antigens, alteration of gut permeability, and the autoinflammatory response of the mucosa due to changes in the microbiota.Citation88 In a survey of IBD patient opinion on the role of diet, a significant proportion of patients felt that dietary factors play a causative role in disease initiation (15.6%) or in disease relapse (57.8%).89s However, diet is difficult to study as it is a multifactorial exposure, and patients may alter dietary habits based on symptom onset prior to diagnoses or as a result of increased disease activity. Carbohydrates have been found to have a secondary rather than causal relationship with IBD when consumed in high concentrations.Citation90 Fiber has also been studied for its potential anti-inflammatory role in the diet, and although there are data to suggest a protective role, the converse is also possible. In a cross-sectional study of dietary habits in patients with CD and compared to controls, the mean dietary fiber intake was 26.6 ± 1.4 g/day for the CD group in comparison to 22.3 ± 0.9 g/day in the control group.Citation91 In another study, high intakes of mono- and disaccharides, and total fats, consistently increased the risk for developing both forms of IBD.Citation92 Linoleic acid has also been associated with an increased risk of UC (OR 2.49, 95% CI 1.23–5.07 for the highest quartile).Citation93 In a case control study of children published in 2008, a positive association with CD was found in girls with a diet rich in meats, fatty foods, and desserts (OR 4.7, 95% CI 1.6–14.2); however, a diet of vegetables, fruits, olive oil, fish, grains, and nuts was inversely associated with CD in both genders (girls: OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–0.9; boys: OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1–0.5).Citation94 Although diet as a risk factor for CD has been studied extensively in the past, there is still a large gap in knowledge due to limitations of retrospective data collection and recall bias for dietary histories.Citation95

Stress and mood

Stress has also been associated with IBD in the literature. Although studies have not been entirely consistent, it is believed that stress contributes not only to development of disease but also to disease exacerbations. In a case control studyCitation96 using univariate analysis, occurrence of stress through life events was found to be more frequent in the 6 month period prior to CD diagnosis when compared to control groups. However, after adjustment for depression and anxiety scores, as well as other characteristics such as smoking status and sociodemographic features, this association appeared to be nonsignificant.Citation96 In a recent prospective study of women, depressive symptoms were associated with an increased risk of CD development (adjusted HR 2.39, 95% CI 1.40–3.98), but not UC development.Citation97 The proposed mechansims for the association between stress and IBD development are alteration in immune function, as well as physiologic changes in the gut mediated by the motor, sensory, and secretory effects of stress.Citation98 In particular, stress may increase intestinal permeability, potentially as a result of alterations in the cholinergic nervous system and mucosal mast cell function.Citation98,Citation99 Data revealing that psychological stress may increase inflammation and worsen the clinical course of immune-mediated inflammatory disease are also increasing.Citation100 A recent study has shown that although short-term stress does not trigger exacerbation in UC, long-term perceived stress increases the risk of fare over a period of months to years.Citation101 Furthermore, in a prospective population based study from Canada by Bernstein et al, perceived stress, negative affect (mood), and major life events were the only triggers significantly associated with fares of IBD.Citation71 In a recent multi-institution cohort, mood or anxiety comorbidity was associated with a 28% increase in the risk of surgery in patients with CD.Citation102 Understanding the role of stress related comorbidities is important in the epidemiology of IBD, as treatment of these disorders may impact disease onset or course.

Conclusion

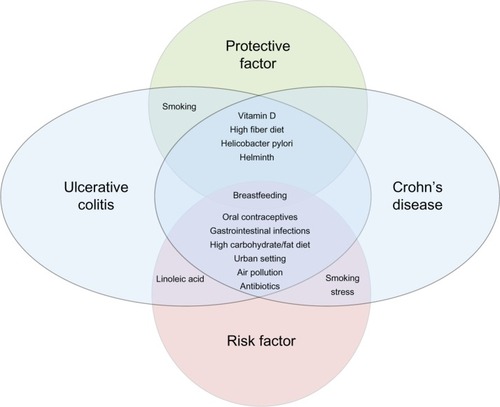

The epidemiology of IBD is evolving. The highest incidence rates of IBD are in Europe and North America, although the overall prevalence of both CD and UC is increasing throughout the world. In particular, disease is emerging in previously low prevalence areas, such as the developing world, and among emigrant populations moving to industrialized, westernized societies. These more recent changes in reported incidence and prevalence are likely due to (1) advances in disease detection and recognition, and (2) continued environmental alterations and exposures impacting IBD onset. The hygiene hypothesis is central to our understanding of environmental exposures and their impact on the immunologic response of the gut mucosa among those genetically susceptible to IBD. These interactions between environmental and genetic influences, and ultimately their effects on the microbiota, are influencing disease onset and course. Interestingly, both protective environmental factors and risk factors have been identified in many studies. Some factors may increase the risk for one disease subtype, while reducing the risk for the other. shows the complicated relationships between these various factors and CD or UC development, based on our current understanding of the limited evidence. Evidence thus far has primarily been retrospective, and subject to recall bias. Thus, better evidence is needed to enhance our understanding of IBD epidemiology. As IBD is a relatively rare disorder, with complicated interactions between potential inciting agents, very large cohorts with detailed, prospectively collected, environmental exposure data will be needed. Of equal importance, particularly to patients with established disease, is a better understanding of the effects of environmental exposures on disease course. Again, large, well-phenotyped cohorts of IBD patients are needed, with detailed prospective collection of environmental exposure data. Ultimately, our goal will be to use such data to design much needed preventative recommendations in those genetically at high risk for IBD, or among those with established disease to help to prevent relapse. Thus, further study in the ever evolving field of IBD epidemiology is warranted.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by a career development award from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (ML).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- MolodeckyNASoonISRabiDMIncreasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic reviewGastroenterology20121424654 e42quiz e3022001864

- NgSCBernsteinCNVatnMHGeographical variability and environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel diseaseGut20136263064923335431

- BenchimolEIFortinskyKJGozdyraPVan den HeuvelMVan LimbergenJGriffithsAMEpidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of international trendsInflamm Bowel Dis20111742343920564651

- LoftusEVJrClinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influencesGastroenterology20041261504151715168363

- BernsteinCNShanahanFDisorders of a modern lifestyle: reconciling the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseasesGut2008571185119118515412

- PrideauxLKammMADe CruzPPChanFKNgSCInflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic reviewJ Gastroenterol Hepatol2012271266128022497584

- MalmborgPGrahnquistLLindholmJMontgomerySHildebrandHIncreasing incidence of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Northern Stockholm County 2002–2007J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr Epub312013

- GrieciTButterAThe incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in the pediatric population of Southwestern OntarioJ Pediatr Surg20094497798019433182

- BernsteinCNRawsthornePCheangMBlanchardJFA population-based case control study of potential risk factors for IBDAm J Gastroenterol2006101993100216696783

- PerminowGBrackmannSLyckanderLGA characterization in childhood inflammatory bowel disease, a new population-based inception cohort from South-Eastern Norway, 2005–2007, showing increased incidence in Crohn’s diseaseScand J Gastroenterol20094444645619117240

- LehtinenPAshornMIltanenSIncidence trends of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Finland, 1987–2003, a nationwide studyInflamm Bowel Dis2011171778178321744433

- PinskVLembergDAGrewalKBarkerCCSchreiberRAJacobsonKInflammatory bowel disease in the South Asian pediatric population of British ColumbiaAm J Gastroenterol20071021077108317378907

- ProbertCSJayanthiVPinderDWicksACMayberryJFEpidemiological study of ulcerative proctocolitis in Indian migrants and the indigenous population of LeicestershireGut1992336876931307684

- Barreiro-de AcostaMAlvarez CastroASoutoRIglesiasMLorenzoADominguez-MunozJEEmigration to western industrialized countries: A risk factor for developing inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Crohns Colitis2011556656922115376

- BenchimolEIGuttmannAGriffithsAMIncreasing incidence of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Ontario, Canada: evidence from health administrative dataGut2009581490149719651626

- FleischerDEGrimmISFriedmanLSInflammatory bowel disease inolder patientsMed Clin North Am199478130313197967911

- GrimmISFriedmanLSInflammatory bowel disease in the elderlyGastroenterol Clin North Am1990193613892194950

- LashnerBAKirsnerJBInflammatory bowel disease in older peopleClin Geriatr Med199172872991855159

- LindnerAEInflammatory bowel disease in the elderlyClin Geriatr Med19991548749710393737

- RobertsonDJGrimmISInflammatory bowel disease in the elderlyGastroenterol Clin North Am20013040942611432298

- SoftleyAMyrenJClampSEInflammatory bowel disease in the elderly patientScand J Gastroenterol Suppl198814427303165553

- AnanthakrishnanANBinionDGTreatment of ulcerative colitis in the elderlyDig Dis200927332733419786760

- KatzSPardiDSInflammatory bowel disease of the elderly: frequently asked questions (FAQs)Am J Gastroenterol20111061889189721862997

- ChoJHBrantSRRecent insights into the genetics of inflammatory bowel diseaseGastroenterology20111401704171221530736

- DensonLALongMDMcGovernDPChallenges in IBD Research: Update on Progress and Prioritization of the CCFA’s Research AgendaInflamm Bowel Dis20131967768223448796

- HalfvarsonJBodinLTyskCLindbergEJarnerotGInflammatory bowel disease in a Swedish twin cohort: a long-term follow-up of concordance and clinical characteristicsGastroenterology20031241767177312806610

- BrantSRUpdate on the heritability of inflammatory bowel disease: the importance of twin studiesInflamm Bowel Dis2011171520629102

- HalfvarsonJGenetics in twins with Crohn’s disease: less pronounced than previously believed?Inflamm Bowel Dis20111761220848478

- HugotJPCezardJPColombelJFClustering of Crohn’s disease within affected sibshipsEur J Hum Genet20031117918412634866

- LaharieDDebeugnySPeetersMInflammatory bowel disease in spouses and their offspringGastroenterology200112081681911231934

- SartorRBMicrobial influences in inflammatory bowel diseasesGastroenterology200813457759418242222

- OlszakTAnDZeissigSMicrobial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer T cell functionScience201233648949322442383

- RoundJLLeeSMLiJThe Toll-like receptor 2 pathway establishes colonization by a commensal of the human microbiotaScience201133297497721512004

- AtarashiKTanoueTShimaTInduction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium speciesScience201133133734121205640

- HviidASvanstromHFrischMAntibiotic use and inflammatory bowel diseases in childhoodGut201160495420966024

- MolodeckyNAKaplanGGEnvironmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseaseGastroenterol Hepatol (N Y)2010633934620567592

- CastiglioneFDiaferiaMMoraceFRisk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases according to the “hygiene hypothesis”: a case-control, multi-centre, prospective study in Southern ItalyJ Crohns Colitis2012632432922405169

- BaronSTurckDLeplatCEnvironmental risk factors in paediatric inflammatory bowel diseases: a population based case control studyGut20055435736315710983

- KlementECohenRVBoxmanJJosephAReifSBreastfeeding and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review with meta-analysisAm J Clin Nutr2004801342135215531685

- BarclayARRussellRKWilsonMLGilmourWHSatsangiJWilsonDCSystematic review: the role of breastfeeding in the development of pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Pediatr200915542142619464699

- KhaliliHAnanthakrishnanANHiguchiLMRichterJMFuchsCSChanATEarly life factors and risk of inflammatory bowel disease in adulthoodInflamm Bowel Dis20131954254723429446

- GearryRBRichardsonAKFramptonCMDodgshunAJBarclayMLPopulation-based cases control study of inflammatory bowel disease risk factorsJ Gastroenterol Hepatol20102532533320074146

- HansenTSJessTVindIEnvironmental factors in inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study based on a Danish inception cohortJ Crohns Colitis2011557758422115378

- FanaroSChiericiRGuerriniPVigiVIntestinal microflora in early infancy: composition and developmentActa Paediatr Suppl200391485514599042

- MidtvedtACMidtvedtTProduction of short chain fatty acids by the intestinal microflora during the first 2 years of human lifeJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr1992153954031469519

- GradelKONielsenHLSchonheyderHCEjlertsenTKristensenBNielsenHIncreased short- and long-term risk of inflammatory bowel disease after salmonella or campylobacter gastroenteritisGastroenterology200913749550119361507

- PorterCKTribbleDRAliagaPAHalvorsonHARiddleMSInfectious gastroenteritis and risk of developing inflammatory bowel diseaseGastroenterology200813578178618640117

- LutherJDaveMHigginsPDKaoJYAssociation between Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis and systematic review of the literatureInflamm Bowel Dis2010161077108419760778

- RamMBarzilaiOShapiraYHelicobacter pylori serology in autoimmune diseases – fact or fiction?Clin Chem Lab Med2012018

- SonnenbergAGentaRMLow prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther20123546947622221289

- OwyangSYLutherJOwyangCCZhangMKaoJYHelicobacter pylori DNA’s anti-inflammatory effect on experimental colitisGut Microbes2012316817122356863

- ElliottDEWeinstockJVWhere are we on worms?Curr Opin Gastroenterol20122855155623079675

- HunterMMMcKayDMReview article: helminths as therapeutic agents for inflammatory bowel diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther20041916717714723608

- ChuKMWatermeyerGShellyLChildhood helminth exposure is protective against inflammatory bowel disease: a case control study in South AfricaInflamm Bowel Dis20131961462023380935

- BlumAMHangLSetiawanTHeligmosomoides polygyrus bakeri induces tolerogenic dendritic cells that block colitis and prevent antigen-specific gut T cell responsesJ Immunol20121892512252022844110

- WalkSTBlumAMEwingSAWeinstockJVYoungVBAlteration of the murine gut microbiota during infection with the parasitic helminth Heligmosomoides polygyrusInflamm Bowel Dis2010161841184920848461

- SummersRWElliottDEUrbanJFJrThompsonRWeinstockJVTrichuris suis therapy in Crohn’s diseaseGut200554879015591509

- SummersRWElliottDEUrbanJFJrThompsonRAWeinstockJVTrichuris suis therapy for active ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled trialGastroenterology200512882583215825065

- KronmanMPZaoutisTEHaynesKFengRCoffinSEAntibiotic exposure and IBD development among children: a population-based cohort studyPediatrics2012130794803

- ShawSYBlanchardJFBernsteinCNAssociation between the use of antibiotics in the first year of life and pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseAm J Gastroenterol20101052687269220940708

- VirtaLAuvinenAHeleniusHHuovinenPKolhoKLAssociation of repeated exposure to antibiotics with the development of pediatric Crohn’s disease – a nationwide, register-based finnish case-control studyAm J Epidemiol201217577578422366379

- ShawSYBlanchardJFBernsteinCNAssociation between the use of antibiotics and new diagnoses of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitisAm J Gastroenterol20111062133214221912437

- KhaliliHHiguchiLMAnanthakrishnanANOral contraceptives, reproductive factors and risk of inflammatory bowel diseaseGut EpubJune12012

- CornishJATanESimillisCClarkSKTeareJTekkisPPThe risk of oral contraceptives in the etiology of inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysisAm J Gastroenterol20081032394240018684177

- TimmerASutherlandLRMartinFOral contraceptive use and smoking are risk factors for relapse in Crohn’s disease. The Canadian Mesalamine for Remission of Crohn’s Disease Study GroupGastroenterology1998114114311509618650

- CosnesJCarbonnelFCarratFBeaugerieLGendreJPOral contraceptive use and the clinical course of Crohn’s disease: a prospective cohort studyGut19994521822210403733

- ZapataLBPaulenMECansinoCMarchbanksPACurtisKMContraceptive use among women with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic reviewContraception201082728520682145

- CipollaGCremaFSaccoSMoroEde PontiFFrigoGNonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and inflammatory bowel disease: current perspectivesPharmacol Res2002461612208114

- AnanthakrishnanANHiguchiLMHuangESAspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and risk for Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis: a cohort studyAnn Intern Med201215635035922393130

- TakeuchiKSmaleSPremchandPPrevalence and mechanism of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced clinical relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseClin Gastroenterol Hepatol2006419620216469680

- BernsteinCNSinghSGraffLAWalkerJRMillerNCheangMA prospective population-based study of triggers of symptomatic fares in IBDAm J Gastroenterol20101051994200220372115

- De SilvaPAnanthakrishnanANVitamin D and IBD: More pieces to the puzzle, still no complete pictureInflamm Bowel Dis2012181391139322180018

- KhaliliHHuangESAnanthakrishnanANGeographical variation and incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among US womenGut2012611686169222241842

- AnanthakrishnanANKhaliliHHiguchiLMHigher predicted vitamin D status is associated with reduced risk of Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology201214248248922155183

- UlitskyAAnanthakrishnanANNaikAVitamin D deficiency in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: association with disease activity and quality of lifeJPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr20113530831621527593

- SoonISMolodeckyNARabiDMGhaliWABarkemaHWKaplanGGThe relationship between urban environment and the inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysisBMC Gastroenterol2012125122624994

- HaugKSchrumpfEHalvorsenJFEpidemiology of Crohn’s disease in western Norway. Study group of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Western NorwayScand J Gastroenterol198924127112752602908

- KaplanGGHubbardJKorzenikJThe inflammatory bowel diseases and ambient air pollution: a novel associationAm J Gastroenterol20101052412241920588264

- AnanthakrishnanANMcGinleyELBinionDGSaeianKAmbient air pollution correlates with hospitalizations for inflammatory bowel disease: an ecologic analysisInflamm Bowel Dis2011171138114520806342

- SonnenbergAOccupational distribution of inflammatory bowel disease among German employeesGut199031103710402210450

- CalkinsBMA meta-analysis of the role of smoking in inflammatory bowel diseaseDig Dis Sci198934184118542598752

- MahidSSMinorKSSotoREHornungCAGalandiukSSmoking and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysisMayo Clin Proc2006811462147117120402

- HiguchiLMKhaliliHChanATRichterJMBousvarosAFuchsCSA prospective study of cigarette smoking and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease in womenAm J Gastroenterol20121071399140622777340

- CosnesJTobacco and IBD: relevance in the understanding of disease mechanisms and clinical practiceBest Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol20041848149615157822

- CosnesJCarbonnelFCarratFBeaugerieLCattanSGendreJEffects of current and former cigarette smoking on the clinical course of Crohn’s diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther1999131403141110571595

- CosnesJSmoking, physical activity, nutrition and lifestyle: environmental factors and their impact on IBDDig Dis20102841141720926865

- LeongRWLauJYSungJJThe epidemiology and phenotype of Crohn’s disease in the Chinese populationInflamm Bowel Dis20041064665115472528

- Chapman-KiddellCADaviesPSGillenLRadford-SmithGLRole of diet in the development of inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis20101613715119462428

- ZallotCQuilliotDChevauxJBDietary beliefs and behavior among inflammatory bowel disease patientsInflamm Bowel Dis201319667222467242

- SilkoffKHallakAYegenaLConsumption of refined carbohydrate by patients with Crohn’s disease in Tel-Aviv-YafoPostgrad Med J1980568428467267494

- KasperHSommerHDietary fiber and nutrient intake in Crohn’s diseaseAm J Clin Nutr19793218981901474481

- GentschewLFergusonLRRole of nutrition and microbiota in susceptibility to inflammatory bowel diseasesMol Nutr Food Res20125652453522495981

- TjonnelandAOvervadKBergmannMMLinoleic acid, a dietary n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, and the aetiology of ulcerative colitis: a nested case-control study within a European prospective cohort studyGut2009581606161119628674

- D’SouzaSLevyEMackDDietary patterns and risk for Crohn’s disease in childrenInflamm Bowel Dis20081436737318092347

- AnanthakrishnanANEnvironmental triggers for inflammatory bowel diseaseCurr Gastroenterol Rep20131530223250702

- LereboursEGower-RousseauCMerleVStressful life events as a risk factor for inflammatory bowel disease onset: A population-based case-control studyAm J Gastroenterol200710212213117100973

- AnanthakrishnanANKhaliliHPanAAssociation between depressive symptoms and incidence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: results from the Nurses’ Health StudyClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201311576222944733

- SajadinejadMSAsgariKMolaviHKalantariMAdibiPPsychological issues in inflammatory bowel disease: an overviewGastroenterol Res Pract2012201210650222778720

- HollanderDInflammatory bowel diseases and brain-gut axisJ Physiol Pharmacol200354Suppl 418319015075459

- RamptonDSThe influence of stress on the development and severity of immune-mediated diseasesJ Rheumatol Suppl201188434722045978

- LevensteinSPranteraCVarvoVStress and exacerbation in ulcerative colitis: a prospective study of patients enrolled in remissionAm J Gastroenterol2000951213122010811330

- AnanthakrishnanANGainerVSPerezRGPsychiatric co-morbidity is associated with increased risk of surgery in Crohn’s diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther20133744545423289600