Abstract

Purpose

To perform a meta-analysis to examine variability among prevalence estimates for CFS/ME, according to the method of assessment used.

Methods

Databases were systematically searched for studies on CFS/ME prevalence in adults that applied the 1994 Centers for Disease Control (CDC) case definition.Citation1 Estimates were categorized into two methods of assessment: self-reporting of symptoms versus clinical assessment of symptoms. Meta-analysis was performed to pool prevalences by assessment using random effects modeling. This was stratified by sample setting (community or primary care) and heterogeneity was examined using the I2 statistic.

Results

Of 216 records found, 14 studies were considered suitable for inclusion. The pooled prevalence for self-reporting assessment was 3.28% (95% CI: 2.24–4.33) and 0.76% (95% CI: 0.23–1.29) for clinical assessment. High variability was observed among self-reported estimates, while clinically assessed estimates showed greater consistency.

Conclusion

The observed heterogeneity in CFS/ME prevalence may be due to differences in method of assessment. Stakeholders should be cautious of prevalence determined by the self-reporting of symptoms alone. The 1994 CDC case definition appeared to be the most reliable clinical assessment tool available at the time of these studies. Improving clinical case definitions and their adoption internationally will enable better comparisons of findings and inform health systems about the true burden of CFS/ME.

Introduction

Chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) is most commonly characterized by fatigue lasting more than 6 months accompanied by symptoms such as muscle and joint pain, sore throat, tender lymph nodes, and cognitive difficulties.Citation1 It is not relieved by rest and results in a substantial reduction in the patient’s activity levels prior to onset.

Studies on the prevalence of this condition have been available since 1990. While most reports have come from the United States and Europe, increasing estimates are emerging from Asia and developing countries, such as Nigeria.Citation2–Citation5 Prevalence varies from as low as 0.2% to as high as 6.41%.Citation6,Citation7 A previous review suggested that the inconsistency is more likely due to differences in study design rather than true differences in prevalence.Citation8 Prior to epidemiological surveys, prevalence was suggested based on clinical reviews of patients in tertiary care.Citation9 The first studies to use prospective sampling methods were based on physician referrals.Citation10–Citation13 Studies gradually began to directly screen samples from primary care clinics,Citation13–Citation18 and the wider community,Citation2,Citation4–Citation6,Citation19–Citation28 through questionnaires and structured interviews. In contrast, larger population based studies first screen medical databases for potential cases.Citation7,Citation16

A particular issue in the development of prevalence studies is case definitions with fundamental differences with respect to inclusion criteria for comorbid and psychiatric conditions. Several studies have demonstrated the difference in prevalence detected according to the case definition used.Citation2,Citation7,Citation14,Citation17,Citation23 In Iceland, for example, prevalence was estimated as 4.8%, 2.4%, and 1.4% using the Australian, Oxford, and 1994 CDC criteria, respectively.Citation23 Even when the same case definition is applied across studies, different methods have been used to ascertain cases. Many studies rely on the self-reporting of symptoms alone,Citation2,Citation4,Citation6,Citation15,Citation19,Citation21,Citation23,Citation25,Citation27 while others rely on complete clinical assessment of symp-toms.Citation3,Citation5,Citation7,Citation14,Citation17,Citation20,Citation22,Citation24,Citation26 However, the effect of study design on prevalence has not been examined.

This paper presents the findings of a meta-analysis performed to assess the consistency between estimates. The aim was to verify whether prevalence varied according to method of assessment used to detect cases. It was hypothesized that prevalence estimates relying on the self-reporting of symptoms would, on average, be higher and less consistent than estimates based on clinical assessment. The assessment was completed using the guidelines of the Meta-analysis for Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group.Citation29

Method

Literature search

Systematic searches of the Medline, Embase, and Pubmed Central databases were conducted using the Medical Search Headings (MeSH terms) “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” (which also captures myalgic encephalomyelitis) and “prevalence.” No limit was applied to years published or language. The strategy also included a secondary search of reference lists of records retrieved from the databases.

Selection of studies

Titles and abstracts were screened for potential studies and full text articles were assessed for suitability. The outcome of interest was prospective studies on the point prevalence of CFS/ME, as defined by the authors of each study. Period prevalence was not considered as it could have resulted in inflated prevalence estimates when compared to point prevalence. Selected studies were based on community or primary care samples, where the condition is most often presented.

Studies on secondary and tertiary care patients were excluded as high-risk groups, as were groups of special interest that did not represent the general population, such as veterans and nurses.

Studies published in languages other than English were also included if detailed English summaries were available. Only studies that applied the 1994 CDC case definition were selected. This was identified as the most widely applied criteria among prevalence studies. This case definition was the most widely accepted definition available at the time of these studies, is also the current criteria used by the CDC, and is more selective than the previously proposed AustralianCitation10 and Oxford criteria.Citation30 Furthermore, only studies on individuals aged 18 years and older were included as the 1994 CDC definition was designed for the detection of CFS/ME in adults.Citation1

Data extraction and analysis

Data on sample size, response rate, number of cases detected, method of assessment (self-reported versus clinical assessment), and sample setting (community versus primary care) were extracted. Sample size was calculated as the total number of participants invited to the study minus the number of non-responders. Prevalence was tabulated as the number of cases detected divided by the sample size, along with standard errors. All estimates were expressed as percentage of the population. Separate tabulations were made according to method of assessment, sample setting, age, and gender. The inverse variance method by DerSimonian and Laird,Citation31 adjusted for random effects, was used to calculate pooled prevalence and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for self-reported and clinically assessed symptoms of CFS/ME. Heterogeneity between studies was tested using the I2 statistic. Sensitivity analysis was performed to test the influence of possible outliers. The meta-analysis was performed in STATA v.10.0. Studies that reported prevalence for more than one study site or for both methods of assessment were treated as separate studies for the purpose of modeling.

Results

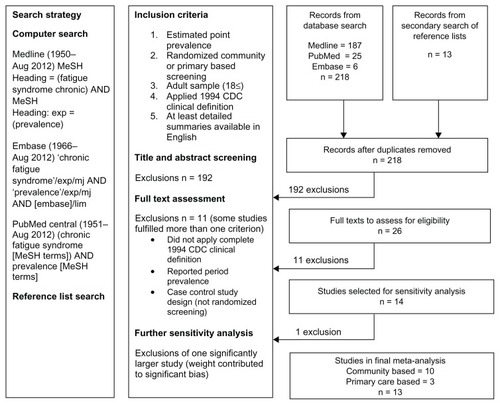

The literature search found 218 records, including 26 prevalence studies that were further assessed for eligibility (). Of these, 11 exclusions were made: 10 did not use the 1994 CDC case definition for CFS/MECitation10–Citation16,Citation19,Citation20,Citation28 (including three reporting period prevalenceCitation12,Citation13,Citation16); and one study recruited participants with acute viral illness as part of a case control design.Citation17 During sensitivity analysis, a further studyCitation7 with a statistical weight of more than 90% was excluded from the investigation.

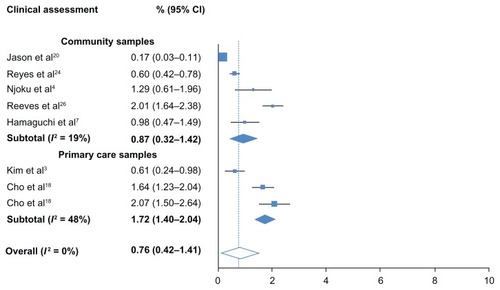

Figure 3 Prevalence of CFS/ME detected by clinical assessment.

Fourteen studies, published between 1995 and 2011, were considered suitable for meta-analysis. Eleven were based on community samples and three were based on primary care samples. Most studies reported CFS/ME cases based on the self-reporting of symptoms alone.Citation2,Citation6,Citation20,Citation21,Citation23,Citation25,Citation27 Three studies reported cases after clinical assessment of symptoms,Citation3,Citation5,Citation18 while four studies provided estimates for both methods.Citation4,Citation22,Citation24,Citation26 Including one study that contributed estimates for two separate study sites (UK and Brazil), a total of 19 estimates were tested by meta-analysis. Insufficient data were found in more than 50% of the studies, thereby preventing the calculation of summaries of age-gender specific prevalence.

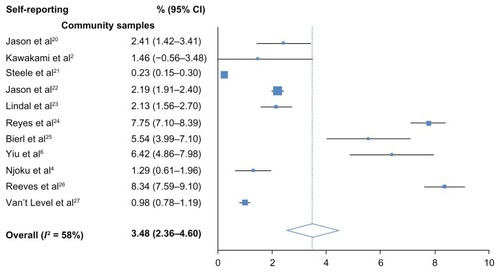

The overall, pooled prevalence for self-reported CFS/ME was 3.48% (95% CI: 2.36–4.60) and high heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 58%). All samples were community-based. The overall, pooled prevalence of CFS/ME detected with clinical assessment was low at 0.76% (95% CI: 0.23–1.29) and no heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 0%). Heterogeneity remained lower than self-reporting studies when estimates were systematically removed during sensitivity analysis. Prevalence however, was lower in community samples (0.87%; 0.32–1.42) than in primary care samples (1.72%; 1.40–2.04). Low heterogeneity (I2 = 19%) was found among community samples. Moderate heterogeneity was detected between the three primary care samples (I2 = 48%).

Discussion

This review demonstrated that high heterogeneity is found among prevalence estimates that rely on the self-reporting of symptoms. This determination was based on community samples only, as available estimates from primary care samples were not eligible for this meta-analysis. Homogeneity, however, was found between studies that completed clinical assessment of symptoms. Furthermore, the findings illustrate that prevalence estimates obtained from self-reporting alone are higher than estimates involving clinical assessment.

Those attending primary care clinics may be a higher risk group than those in the general community. Slightly higher prevalence was found in primary care, but this was more likely due to the limited availability of studies. This also made the heterogeneity detected among primary care samples highly sensitive to the lower prevalence detected in a Korean sample.Citation3 However, the variability among community samples that used clinical assessment was still low compared to community samples relying on self-reporting.

This systematic review used specific inclusion criteria to minimize a biased selection of studies. The majority of exclusions were studies based on dated definitions of CFS/ME. A UK studyCitation7 based on nationwide screening was also removed due to its large statistical weighting. If included, the results of the remaining studies would not have been detected by the meta-analysis. Prevalences were adjusted for no response or participation. This may have resulted in higher estimates, as it assumes that non-responders are not less likely to have CFS/ME.

Although there are studies that rely on self-reporting to determine the official prevalence of CFS/ME,Citation2,Citation6,Citation23,Citation27 many use it as an initial screening technique to source potential cases of CFS/ME and assess the feasibility of conducting larger epidemiological surveys. In such cases, those that report symptoms fulfilling the clinical definition of CFS/ME have often been referred to as CFS/ME-like cases.Citation21,Citation24–Citation27 It is not uncommon for studies to apply further tools to help verify suspicions of CFS/ME, such as empirical criteria,Citation32 validated health surveys,Citation33 fatigue scores,Citation34 and depression scales.Citation35 Some studies have then proceeded with clinical diagnosis of CFS/ME. Different approaches to clinical assessment can be found; one study evaluated all participants as part of a random health check of the population.Citation5 Some studies evaluated those reporting CFS/ME symptoms,Citation18,Citation36 while others only evaluated a sample reporting CFS/ME symptoms.Citation4,Citation22,Citation24,Citation26 The latter may have resulted in conservative estimates as cases may have been detected in those not assessed.

The differences found in heterogeneity due to method of assessment highlight the need for collaborative research in CFS/ME prevalence where similar methods are applied across study sites. This has only been demonstrated by one study that found similar prevalences of CFS/ME in Brazil (1.64%; 95% CI: 1.23–2.04) and the UK (2.07%; 1.50–2.64).Citation18 The current meta-analysis particularly illustrates that prevalence is more consistent across samples when clinical assessment is involved. Therefore, it is recommended that studies combine the use of a standard case definition with clinical verification of symptoms. More specific definitions are now available, such as the recently released International Consensus definition.Citation32 Their use to assess prevalence should also help produce more reliable estimates in the future.

Conclusion

Prevalence estimates for CFS/ME based on self-reporting alone should be viewed with caution. Clinically valid diagnoses are vital in undertaking accurate prevalence studies for CFS/ME. The findings of this study are based on CFS/ME as defined by the CDC. As new advances are made in clinical case definitions, for example, through the International Consensus definition, further valid prevalence studies may be expected.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FukudaKStrausSEHickieISharpeMCDobbinsJGKomaroffAThe chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study GroupAnn Intern Med1994121129539597978722

- KawakamiNIwataNFujiharaSKitamuraTPrevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in a community population in JapanTohoku J Exp Med1998186133419915105

- KimCHShinHCWonCWPrevalence of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome in Korea: community-based primary care studyJ Korean Med Sci200520452953416100439

- NjokuMGJasonLATorres-HardingSRThe prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in NigeriaJ Health Psychol200712346147417439996

- HamaguchiMKawahitoYTakedaNKatoTKojimaTCharacteristics of chronic fatigue syndrome in a Japanese community population: chronic fatigue syndrome in JapanClin Rheumatol201130789590621302125

- YiuYMQiuMYA preliminary epidemiological study and discussion on traditional Chinese medicine pathogenesis of chronic fatigue syndrome in Hong KongZhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao200535359362 Chinese16159567

- NaculLCLacerdaEMPhebyDPrevalence of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) in three regions of England: a repeated cross-sectional study in primary careBMC Med201199121794183

- RanjithGEpidemiology of chronic fatigue syndromeOccup Med (Lond)2005551131915699086

- MurdochJCMyalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) syndrome-an analysis of the clinical findings in 200 casesN Z Fam Physician1987145154

- LloydARHickieIBoughtonCRSpencerOWakefieldDPrevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in an Australian populationMed J Aust199015395225282233474

- Ho-YenDOMcNamaraIGeneral practitioners’ experience of the chronic fatigue syndromeBr J Gen Pract1991413493243261777276

- GunnWJConnellDBRandallBEpidemiology of chronic fatigue syndrome: the Centers for Disease Control StudyCiba Found Symp19931738393 discussion 93–1018387910

- ReyesMGaryHEJrDobbinsJGSurveillance for chronic fatigue syndrome – four US cities, September 1989 through Aug 1993MMWR CDC Surveill Summ199746211312412768

- BatesDWSchmittWBuchwaldDPrevalence of fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome in a primary care practiceArch Intern Med199315324275927658257251

- LawrieSMPelosiAJChronic fatigue syndrome in the community. Prevalence and associationsBr J Psychiatry199516667937977663830

- VersluisRGde WaalMWOpmeerCPetriHSpringerMPPrevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in 4 family practices in LeidenNed Tijdschr Geneeskd19971413115231526 Dutch9543740

- WesselySChalderTHirschSWallacePWrightDThe prevalence and morbidity of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective primary care studyAm J Public Health1997879144914559314795

- ChoHJMenezesPRHotopfMBhugraDWesselySComparative epidemiology of chronic fatigue syndrome in Brazilian and British primary care: prevalence and recognitionBr J Psychiatry2009194211712219182171

- PriceRKNorthCSWesselySFraserVJEstimating the prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome and associated symptoms in the communityPublic Health Rep199210755145221329134

- JasonLATaylorRWagnerLEstimating rates of chronic fatigue syndrome from a community-based sample: a pilot studyAm J Community Psychol19952345575688546110

- SteeleLDobbinsJGFukudaKThe epidemiology of chronic fatigue in San FranciscoAmerican J Med19981053A83S90S

- JasonLARichmanJARademakerAWA community-based study of chronic fatigue syndromeArch Intern Med1999159182129213710527290

- LindalEStefanssonJGBergmannSThe prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in Iceland – a national comparison by gender drawing on four different criteriaNord J Psychiatry200256427327712470318

- ReyesMNisenbaumRHoaglinDCPrevalence and incidence of chronic fatigue syndrome in Wichita, KansasArch Intern Med2003163131530153612860574

- BierlCRegional distribution of fatiguing illnesses in the United States: a pilot studyPopul Health Metr200421114761250

- ReevesWCJonesJFMaloneyEPrevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in metropolitan, urban, and rural GeorgiaPopul Health Metr20075517559660

- van’t LevenMZielhuisGAvan der MeerJWVerbeekALBleijenbergGFatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome-like complaints in the general populationEur J Public Health201020325125719689970

- BhuiKSDinosSAshbyDNazrooJWesselySWhitePDChronic fatigue syndrome in an ethnically diverse population: the influence of psychosocial adversity and physical inactivityBMC Med201192621418640

- StroupDFBerlinJAMortonSCMeta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) groupJAMA2000283152008201210789670

- SharpeMCArchardLCBanatvalaJEA report – chronic fatigue syndrome: guidelines for researchJ R Soc Med19918421181211999813

- DerSimonianRLairdNMMeta-anaysis in clinical trialsControl Clin Trials198671771883802833

- LevinePHEpidemic neuromyasthenia and chronic fatigue syndrome: epidemiological importance of a cluster definitionClin Infect Dis199418 Suppl 1S16S208148446

- SheaSCBarneyCMacrotraining: a “how-to” primer for using serial role-playing to train complex clinical interviewing tasks such as suicide assessmentPsychiatr Clin North Am2007302e1e2917643828

- ColsonPTamaletCRaoultDSVARAP and aSVARAP: simple tools for quantitative analysis of nucleotide and amino acid variability and primer selection for clinical microbiologyBMC Microbiol200662116515699

- HouseKIrelandAJSherriffMAn investigation into the use of a single component self-etching primer adhesive system for orthodontic bonding: a randomized controlled clinical trialJ Orthod20063313844 discussion 2816514132

- KimSHLeeKLimHSPrevalence of chronic widespread pain and chronic fatigue syndrome in Korean livestock raisersJ Occup Health200850652552818946188