Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a chronic fibrotic lung disease of unknown cause that occurs in adults and has a poor prognosis. Its epidemiology has been difficult to study because of its rarity and evolution in diagnostic and coding practices. Though uncommon, it is likely underappreciated both in terms of its occurrence (ie, incidence, prevalence) and public health impact (ie, health care costs and resource utilization). Incidence and mortality appear to be on the rise, and prevalence is expected to increase with the aging population. Potential risk factors include occupational and environmental exposures, tobacco smoking, gastroesophageal reflux, and genetic factors. An accurate understanding of its epidemiology is important, especially as novel therapies are emerging.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a specific form of chronic progressive fibrotic lung disease of unknown cause.Citation1,Citation2 It occurs primarily in middle-aged to older adults and is characterized by the underlying histopathological pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia. Its pathobiology is complex and is hypothesized to be driven by the loss of alveolar epithelial cell integrity due to aging, genetic and epigenetic factors, and reactivation of developmental signaling pathways.Citation3 Progressive fibrosis with loss of normal lung tissue leads to restricted ventilation, impaired gas exchange, respiratory symptoms and exercise limitation, poor quality of life, and ultimately death. Unfortunately, there are no definitive therapies for IPF, with only one drug shown to potentially slow the progression of disease in clinical trials,Citation4 and surgical therapy with lung transplantation available to only a small minority of patients.

We are living in a time of great opportunity and promise in the field of IPF. With central advances in our understanding of disease mechanism, the development of novel agents by academia and industry, and the formation of multicenter networks experienced in the conduct of large clinical trials, there is good reason to believe that we are on the verge of developing multiple effective therapies. As the management options for IPF patients improve, an accurate understanding of the epidemiology of IPF will be important so that health care systems and policy-makers are adequately prepared to facilitate care.

Historical challenges in studying the epidemiology of IPF

The epidemiology of IPF remains poorly described for many reasons, but changes in definitions of IPF and complex diagnostic algorithms have proven major challenges. Since the early pathological descriptions of interstitial pneumonia by Hamman and Rich in 1944,Citation5 multiple conditions that we now consider separate disease entities (eg, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia and desquamative interstitial pneumonia) were lumped in with IPF or one of its other names (eg, cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis). In 1998, Katzenstein and Myers proposed that the term IPF be reserved for those patients with a histopathological pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia and no identifiable cause for their interstitial lung disease (ILD).Citation6 This concept was formalized into diagnostic criteria in the first international consensus statement on IPF in 2000Citation1 and revised in 2011 ().Citation2 Additionally, these statements have emphasized the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to accurate diagnosis through consensus that includes discussion among pulmonologists, radiologists, and pathologists with expertise in ILDs. This evolution is reflected in the confusing nomenclature of International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes that have historically encompassed the disease ().

Table 1 Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and International Classification of Disease (ICD) code nomenclature

Prevalence and incidence

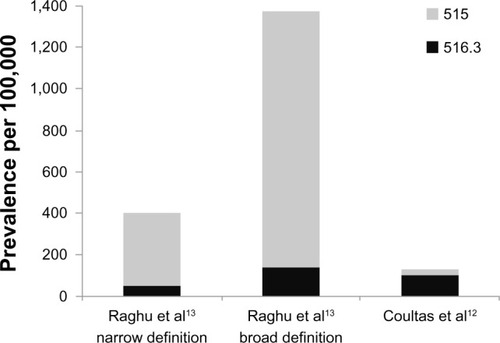

The published literature suggests that IPF is the first or second most commonly encountered ILD in pulmonology practices (range 17%–86%).Citation7–Citation11 Its overall incidence and prevalence, however, are unclear (). Geographically, most studies come from the United StatesCitation12–Citation14 and Europe (United Kingdom,Citation15,Citation16 Czech Republic,Citation17 Norway,Citation18 Finland,Citation19 Greece,Citation8 and TurkeyCitation9), with only two studies reported from Asia (JapanCitation11 and TaiwanCitation20). Most of these studies included patients diagnosed prior to the redefinition of IPF in 2000, and strategies for case ascertainment within the source population varied from exclusive reliance on diagnostic codes (low diagnostic specificity), to surveys of clinicians at subspecialty clinics (low diagnostic sensitivity), to a combination of searching administrative data and focused review of medical records (potentially improving diagnostic sensitivity and specificity). With these issues in mind, the published prevalence of IPF has ranged from 0.7 per 100,000 in Taiwan to 63.0 per 100,000 in the United States, and the published incidence has ranged from 0.6 per 100,000 person years to 17.4 per 100,000 person years (). It is unclear how much of this variation among studies is due to geographic or demographic differences in the risk of IPF. Below is a brief overview of selected studies.

Table 2 Prevalence and incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis by geography

United States

Coultas et alCitation12

This study used multiple sources including clinician surveys, pathology reports, discharge diagnoses, death certificates, and autopsies from Bernalillo County, New Mexico between 1988 and 1990. Using the diagnostic code for idiopathic fibrosing alveolitis (ICD-9 code 516.3), an overall prevalence of IPF of 13.2 per 100,000 for women and 20.2 per 100,000 for men (incidence 7.4 per 100,000 person years and 10.7 per 100,000 person years for men and women, respectively) were reported.

Raghu et alCitation13

This study queried a large private health insurance claims database that included patients from 20 states in the United States for calendar year 2000. Cases were again identified by ICD-9 code 516.3 and exclusion of associated conditions (broad definition), with a subgroup analysis requiring additional claims for lung biopsy or chest computed tomography scan, indicating a relevant diagnostic evaluation had taken place (narrow definition). The prevalence was 42.7 per 100,000 (14 per 100,000 for the narrow definition) and the incidence was 16.3 per 100,000 person years (6.8 per 100,000 person years for the narrow definition). This translated to an estimated 89,000 patients living with IPF in the United States in the year 2000 with 34,000 new cases diagnosed per year.

Both the Coultas and Raghu studies also provided estimates using the more generic diagnostic code for postinflammatory pulmonary fibrosis (ICD-9 code 515). demonstrates the impact of this more inclusive (ie, more sensitive, less specific) definition. The wide variation in the prevalence of ICD-9 code 515 between studies may reflect methodological and/or coding practice differences.

Figure 1 The prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis varies widely depending on case definitions in epidemiologic studies.

Fernández-Pérez et alCitation14

This was a small population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1997–2005 (source population of approximately 128,000 primarily White, residents) utilizing a county-wide medical record linkage system. Cases were first identified by administrative codes and then verified via audit of patient-level data in accordance with the revised IPF definition. Investigators identified a total of 47 cases meeting the primary case definition corresponding to an age and sex-adjusted prevalence of 63 per 100,000 and an incidence of 17.4 per 100,000 person years. Incidence rates decreased over the study period.

Europe

Gribbin et alCitation15

This study interrogated a longitudinal primary care database representing 25% of practices within the United Kingdom for the diagnostic terms cryptogenic or idiopathic fibrosing alveolitis between 1991 and 2003. An audit of IPF cases in this database found that 19 of 20 were accurate, supporting diagnostic validity, although the audit occurred prior to the revised criteria.Citation21 The overall annual incidence of IPF was 4.6 per 100,000 person years.Citation15 Incidence increased over the study period, about 11% per year. The investigators reported a follow up study with similar methods, albeit with slightly more inclusive search terms, for patients identified from 2000–2009, and found that incidence continued to increase.Citation16 The increasing incidence was not accounted for by the effect of an aging population.

von Plessen et alCitation18

This study searched multiple ICD-8 and ICD-9 codes in one hospital district in Norway between 1984 and 1998. Medical records were reviewed and cases excluded if alternative diagnoses appeared more likely. Prevalence was found to be 23.4 per 100,000, and the incidence was 4.3 per 100,000 person years.

Hodgson et alCitation19

These researchers performed a nation-wide survey of pulmonary practices in Finland and searched hospital databases for ICD-10 code J84.1 in 1997–1998. A case audit was performed at a subset of centers finding that 49%–77% met revised diagnostic criteria. Prevalence was found to be 16 to 18 per 100,000.

Karakatsani et alCitation8

In Greece, this study surveyed pulmonary specialty clinics in 2004 for cases of ILD (an approach likely to underestimate disease occurrence compared to population-based approaches), with clinicians instructed to apply consensus criteria. The reported prevalence (3.4 per 100,000) and incidence (0.9 per 100,000 person years) of IPF were much lower than other reports from the United States and Europe.

Asia

Ohno et alCitation11

These investigators searched medical benefit certificates for all idiopathic interstitial pneumonias in Japan in 2005, with clinical data available for review in 35% of cases. The incidence of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia was 3.4 per 100,000 person years, and 85.7% were considered due to IPF.

Lai et alCitation20

This study searched the Taiwanese national health insurance system for ICD-9 code 516.3 from 1997 to 2007 and applied narrow and broad case definitions similar to the Raghu et alCitation13 study. The prevalence was 0.7 to 6.4 per 100,000, and the incidence was 0.6 to 1.4 per 100,000 person years.

In both the Ohno and Lai studies, disease severity was high, suggesting that the lower estimates were due to low case ascertainment rates, with only more severe cases recognized.

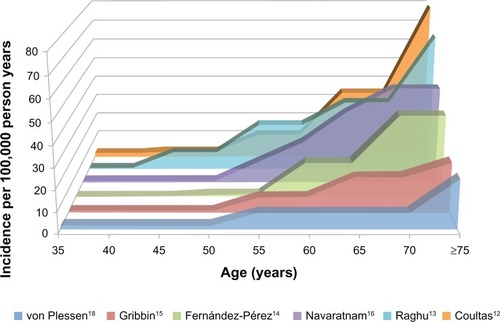

Many of the above studies evaluated rates of IPF by age and sex. Prevalence and incidence of IPF are clearly higher in older age groups (), a finding consistent with the role of aging in the pathogenesis of IPF.Citation3 IPF also appears to be more common in men compared to women, however, some postulate this may be due to sex differences in historical smoking patterns rather than an inherent sex-related risk for IPF.Citation22,Citation23

Figure 2 The incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis increases with age.

Risk factors

Several potential risk factors for the development of IPF have been identified. These include environmental and occupational exposures, tobacco smoking, comorbidities (in particular gastroesophageal reflux disease [GERD]), and genetic polymorphisms (). The identification of risk factors for IPF is critically important as it may inform prevention strategies, early diagnosis, and novel therapies.

Table 3 Proposed risk factors for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Inhaled exposures

Multiple lines of evidence lend support to the plausibility of inhaled exposures contributing to at least some cases of IPF.Citation24 First, basic science and animal studies support the concept of repetitive alveolar epithelial cell stress due to an array of potential inciting agents in the pathogenesis of IPF.Citation3,Citation24 Second, epidemiologic studies have observed geographic variation within countries in the occurrence of IPF, particularly in highly industrialized regions.Citation25 There is also a higher occurrence in men compared to women who, at least historically, were more likely to smoke and to work in dusty occupations.Citation12,Citation23,Citation26 Third, well-defined occupational lung diseases such as asbestosis and silicosis clearly cause fibrotic lung disease,Citation27,Citation28 leaving open the possibility that less well-characterized exposures may do so as well. Fourth, autopsy studies have revealed higher levels of inorganic particles, such as silicon and aluminum, in the hilar lymph nodes of patients with IPF compared to controls.Citation29

With these observations in mind, several studies have demonstrated an association of certain environmental and occupational exposures with IPF.Citation24 As with incidence and prevalence estimation studies, diagnostic misclassification (particularly for studies performed prior to the IPF statements) introduces the potential for faulty associations.

In 2006, Taskar and Coultas reviewed six case-control studies, performed in three countries (United States, United Kingdom, Japan), that compared a total of 711 patients with IPF to 1,491 controls.Citation24 Exposures with significant associations in at least one study included agriculture/farming, hairdressing, birds, animal/vegetable dust, livestock, wood dust, textile dust, mold, metal dust, stone/sand/silica, wood fires, and tobacco smoking.Citation30–Citation35 Meta-analysis of exposures with at least two studies demonstrated a significant association for agriculture/farming (odds ratio [OR] 1.65, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.20–2.26, and population attributable risk [PAR] 20.8%), livestock (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.28–3.68, PAR 4.1%), wood dust (OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.34–2.81, PAR 5.0%), metal dust (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.74–3.40, PAR 3.4%), stone/sand/silica (OR 1.97, 95% CI 1.09–3.55, PAR 3.5%), and smoking (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.27–1.97, PAR 49.1%).Citation24 A dose-response has been suggested for metal dust exposureCitation34 and moderate smoking history.Citation35,Citation36 Smoking has also been associated with a higher risk of developing familial pulmonary fibrosis with an age and sex-adjusted odds ratio of 3.6 (95% CI 1.2–9.8).Citation37

Hubbard et al examined death certificates from pension fund archives at a major metal engineering company from 1967–1997, finding a mortality rate from IPF among workers higher than that expected in the general population (proportional mortality ratio 1.39, 95% CI 1.07–1.82).Citation38 They further examined the lifetime occupational records for a subgroup of cases and controls, and found a significant association of IPF with the duration of working with metal (OR per 10 years 1.71, 95% CI 1.09–2.68). In 1994 in Japan, Iwai et al examined occupational data on autopsy records from 1,311 patients with IPF compared to 393,000 controls and found a significant association with metal workers, wood workers, painters, and barbers/beauticians.Citation31

Four more recent case-control studies have been published from Sweden, the United States, Mexico, and Egypt. In Sweden, Gustafson et al found no relationship with metal dust exposure or the general category of wood dust exposure, though they did find significant associations for men with birch and hardwood dust exposure.Citation39 In the United States, Pinheiro et al used national death certificate data from 1999–2003 comparing ICD-10 code J84.1 with matched controls, finding an increased proportionate mortality for metal mining (2.34, 95% CI 1.3–4.0) and fabricated structural metal products (1.9, 95% CI 1.1–3.1).Citation40 In Mexico, García-Sancho et al found a significant association for occupational exposure to dusts, smoke, gases, or chemicals.Citation41 Finally, in Egypt, Awadalla et al performed a multicenter hospital-based case control study from 2010 to 2011.Citation42 Significant associations were found for occupations in woodworking and chemical/petrochemical industry for men and raising birds and farming for women.

Gastroesophageal reflux

There is strong evidence linking GERD to the presence and progression of IPF, but causation is unproven. GERD is hypothesized to lead to chronic microaspiration of gastric contents, both acid and nonacid, causing repetitive lung injury and resulting pulmonary fibrosis in susceptible individuals.Citation43 This concept is supported by animal studies,Citation43 an elevated prevalence of GERD in patients with IPF (67%–94%),Citation44–Citation47 and an association in retrospective studies of GERD treatment with improved survival and reduced disease progression in IPF.Citation48,Citation49 Interestingly, less than half of IPF patients with abnormal gastroesophageal reflux report classic symptoms (eg, heartburn, regurgitation) making it difficult to identify these patients clinically.Citation44–Citation47

Genetics

Familial IPF is defined as IPF occurring in two or more first-degree relatives within the same biologic family.Citation2,Citation50 Familial IPF is thought to represent <5% of cases of IPF and is generally indistinguishable from sporadic cases.Citation51 Genes associated with familial IPF include telomerase-related genes (TERT and TERC),Citation52,Citation53 surfactant proteins C (SPC)Citation54–Citation56 and A2 (SPA2)Citation57, and ELMOD2.Citation58 Mutations in TERT or TERC have been identified in about 18% of familial IPF and less commonly in sporadic cases.Citation52,Citation53,Citation59 These mutations result in shortened telomere lengths in both affected individuals and asymptomatic carriers, and shortened telomere lengths have also been demonstrated in noncarrier family members, suggesting an epigenetic inheritance of short telomeres.Citation52,Citation53 Also, 25% of sporadic and 37% of familial cases without TERT/TERC mutations have short telomeres, suggesting other mechanisms for telomere shortening that are not due to mutations in TERT/TERC.Citation60 Finally, the pulmonary fibrosis in TERT mutation families is age-dependent, associated with smoking, and confers a survival prognosis similar to sporadic IPF.Citation61 The telomere story in IPF provides important potential pathogenic links with epidemiologic observations of increased risk of IPF with aging and smoking.

A common single nucleotide polymorphism in the promoter region of the mucin 5B gene (MUC5B) was discovered in 38% of sporadic IPF cases and 9% of controls.Citation62 The association was found to be allele dose-dependent and has been replicated in independent cohorts.Citation62,Citation63 Interestingly, while the MUC5B promoter polymorphism appears to confer increased risk of developing IPF, it may be associated with improved survival in established IPF.Citation64 Finally, two large genome-wide association studies have recently confirmed associations with TERT, TERC, and MUC5B as well as other novel loci (eg, TOLLIP), some of which are thought to be involved in host defense, cell-cell adhesion, and DNA repair.Citation65,Citation66

Heath care resource utilization and burden of illness

Until recently, little was known about health care resource utilization and burden of illness related to IPF. Most of the literature has focused on hospitalizations which are costly and associated with a poor prognosis similar to other chronic respiratory diseases.Citation67 In IPF, hospital admissions are often due to respiratory worsening and are associated with reduced survival.Citation68–Citation70 At least half of hospitalizations are thought to be due to acute exacerbations of IPF, defined as respiratory worsening over less than 1 month without an identifiable secondary cause, such as infection.Citation69,Citation71 Based mostly on retrospective studies, the annual incidence of acute exacerbations of IPF ranges from approximately 5%–20%, with a mortality rate of 20%–100%.Citation69,Citation71 In their population-based study, Fernández-Pérez et al found that 79% of IPF patients in Olmsted county, Minnesota required one or more hospitalizations for acute respiratory worsening at a rate of 0.13 hospitalizations per patient year.Citation14 In the UK, Navaratnam et al explored hospitalization for IPF from 1998 to 2010.Citation72 The admission rate for ICD-10 code J84.1 averaged 14.95 per 100,000 person years and increased by approximately 5% per year. Admission rates were greater in older patients and in men. The average length of stay decreased from 7.2 days to 5.1 days, but the estimated financial burden of hospitalization increased from £12 million to £16.2 million per year.

Collard et al assessed the overall burden of illness in IPF including comorbidities, health care resource utilization, and health care costs by searching two United States insurance claims databases between 2001 and 2008.Citation73 Cases of IPF required both age >55 years old and at least two claims of ICD-9 code 516.3 or one claim each with ICD-9 code 516.3 and 515. An age and sex-matched population lacking these codes was used for control comparisons. Pulmonary hypertension, emphysema, pulmonary embolism, chronic bronchitis, pulmonary infection, and lung cancer were all more common in IPF patients than controls. Risk was also increased for many common chronic diseases, such as coronary artery disease, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and GERD. The all-cause hospitalization rate (0.5 per person year), the days in hospital (3.1 days per person year), and the outpatient visit rate (28 visits per person year) were two-fold higher than for controls, and the inpatient death rate was more than three-fold higher than for controls. The average annual direct costs were about two-fold higher for IPF patients compared to controls, amounting to an incremental annual cost of $12,124. Based on a prevalence of 89,000 patients with IPF in the United States,Citation13 it was estimated that the aggregate incremental cost due to IPF was over $1 billion per year.

Mortality

IPF-related mortality refers to the proportion of people dying per year in the general population in whom IPF is considered the underlying cause of death or an associated cause of death. IPF-related mortality data are typically obtained from national registries compiled from information on death certificates. These studies are generally limited by disease under-recognition (patients with IPF are not captured) and diagnostic misclassification (patients with IPF are mislabeled). Coultas and Hughes evaluated death certificates for 129 patients with a known clinical diagnosis of ILD.Citation7 Looking at potential IPF cases (ICD-9 code 515 and 516.3 combined), 36 of 71 patients with the diagnosis prior to death had it listed anywhere on the death certificate (diagnostic sensitivity 51%). There was a high degree of reclassification between ICD-9 codes 515 and 516.3 comparing predeath and death certificate diagnoses. Johnston et al reported similar findings.Citation26 These data taken together suggest that mortality data from national death registries underestimate IPF-related mortality.

Three studies examined mortality from IPF in the 1970s to early 1990s in the United Kingdom, United States, Germany, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada.Citation22,Citation26,Citation74 Major findings were that IPF-related mortality 1) increased in most countries over this time period, 2) was higher in older patients and in men, and 3) had regional variations within countries. These studies also highlighted a marked difference in rates of ICD-9 code 516.3 versus 515 among the countries, reflecting differences in country-specific coding practices.

Olson et al investigated mortality rates in IPF by searching the United States death registry from 1992 to 2003.Citation23 IPF was identified as records containing ICD-9 code 516.3 or 515 (from 1992–1998) and ICD-10 code J84.1 (from 1998–2003) excluding those containing codes for other ILDs. The average age and sex-adjusted mortality was 5.08 per 100,000 person years, which is similar to contemporary incidence estimates in the United States (6.8 per 100,000 patients yearsCitation2 to 8.8 per 100,000 patient years).Citation14 Mortality was higher than previously reportedCitation22 and increased by 34% over the study period. Although mortality rates were higher for men compared to women, they increased more rapidly in women, potentially due to changes in smoking patterns. Mortality rates were higher in older age groups and in Whites compared to Blacks and Hispanics. IPF was the most common underlying cause of death in patients with IPF (60%), with other common causes including ischemic heart disease, lung cancer, pneumonia, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, and pulmonary embolism. Interestingly, the proportion of patients dying from IPF, rather than with IPF, was greater in this study than in previous reports.Citation22 The authors speculate this may be due to effective therapies for competing causes of death, such as cardiovascular disease, outpacing those for IPF.

In a follow up study using similar methods during the years 1989 to 2007, these investigators further explored racial and ethnic differences in IPF mortality.Citation75 Of all IPF-related deaths, 87.2% occurred in Whites, 5.1% in Blacks, 5.4% in Hispanics, and 2.2% in other racial/ethnic groups. Compared to Whites, Blacks were less likely (OR 0.47) and Hispanics (OR 1.45) and other groups (1.29) more likely to have IPF encoded on their death certificates after adjusting for age and sex.

Navaratnam et al searched national mortality statistics in the United Kingdom for underlying cause of death from 1968 to 2008 using ICD-8, ICD-9, and ICD-10 codes spanning this period.Citation16 Mortality, standardized to the 2008 population, increased from 0.92 per 100,000 person years in 1968–1972 to 5.1 per 100,000 person years in 2005–2008; an annual increase of 5% after controlling for age and sex. Again, mortality rates were higher in men and older age groups.

Whether the increasing mortality from IPF is due to a true increase in mortality or is a consequence of recognition or reporting bias is uncertain. In public health terms, IPF-related mortality is similar in magnitude to that of many malignancies (eg, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, renal cancer, esophageal cancer).Citation76

Conclusion

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is an uncommon disease, but its incidence and prevalence appear to be increasing, and may be higher than reported in the literature because of reporting and recognition bias. There is still a lot we have to learn about the epidemiology of the disease; at present, there are entire continents without any available data on the occurrence of IPF. The risk of developing IPF is likely due to both host and environmental factors, and their elucidation may lead to improved prevention and treatment strategies. The personal and financial costs of IPF are substantial, and therapies to reduce the burden of illness from IPF are sorely needed.

Disclosure

HRC has served as consultant for Biogen, FibroGen, Genoa, Gilead, InterMune, MedImmune, Promedior, and Pfizer; has received grants from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Genentech, and the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; has received royalties from UpToDate; and has received payment for development of educational presentations from MedScape. BL reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- American Thoracic SocietyIdiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS)Am J Respir Crit Care Med20001612 Pt 164666410673212

- RaghuGCollardHREganJJATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary FibrosisAn official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and managementAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011183678882421471066

- KingTEJrPardoASelmanMIdiopathic pulmonary fibrosisLancet201137898071949196121719092

- NoblePWAlberaCBradfordWZCAPACITY Study GroupPirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trialsLancet201137797791760176921571362

- HammanLRichARAcute diffuse interstitial fibrosis of the lungsBull Johns Hopkins Hospital194474177212

- KatzensteinALMyersJLIdiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: clinical relevance of pathologic classificationAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981574 Pt 1130113159563754

- CoultasDBHughesMPAccuracy of mortality data for interstitial lung diseases in New Mexico, USAThorax19965177177208882079

- KarakatsaniAPapakostaDRaptiAHellenic Interstitial Lung Diseases GroupEpidemiology of interstitial lung diseases in GreeceRespir Med200910381122112919345567

- MusellimBOkumusGUzaslanETurkish Interstitial Lung Diseases Group. Epidemiology and distribution of interstitial lung diseases in TurkeyClin Respir J Epub5272013

- ThomeerMJCostabeURizzatoGPolettiVDemedtsMComparison of registries of interstitial lung diseases in three European countriesEur Respir J Suppl200132114s118s11816817

- OhnoSNakayaTBandoMSugiyamaYIdiopathic pulmonary fibrosis – results from a Japanese nationwide epidemiological survey using individual clinical recordsRespirology200813692692818657060

- CoultasDBZumwaltREBlackWCSobonyaREThe epidemiology of interstitial lung diseasesAm J Respir Crit Care Med199415049679727921471

- RaghuGWeyckerDEdelsbergJBradfordWZOsterGIncidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisAm J Respir Crit Care Med2006174781081616809633

- Fernández PérezERDanielsCESchroederDRIncidence, prevalence, and clinical course of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a population-based studyChest2010137112913719749005

- GribbinJHubbardRBLe JeuneISmithCJWestJTataLJIncidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis in the UKThorax2006611198098516844727

- NavaratnamVFlemingKMWestJThe rising incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the UKThorax201166646246721525528

- KolekVEpidemiology of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in Moravia and SilesiaActa Univ Palacki Olomuc Fac Med199413749507778506

- von PlessenCGrindeOGulsvikAIncidence and prevalence of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in a Norwegian communityRespir Med200397442843512693805

- HodgsonULaitinenTTukiainenPNationwide prevalence of sporadic and familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence of founder effect among multiplex families in FinlandThorax200257433834211923553

- LaiCCWangCYLuHMIdiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Taiwan – a population-based studyRespir Med2012106111566157422954482

- HubbardRVennALewisSBrittonJLung cancer and cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. A population-based cohort studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med200016115810619790

- ManninoDMEtzelRAParrishRGPulmonary fibrosis deaths in the United States, 1979–1991. An analysis of multiple-cause mortality dataAm J Respir Crit Care Med19961535154815528630600

- OlsonALSwigrisJJLezotteDCNorrisJMWilsonCGBrownKKMortality from pulmonary fibrosis increased in the United States from 1992 to 2003Am J Respir Crit Care Med2007176327728417478620

- TaskarVSCoultasDBIs idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis an environmental disease?Proc Am Thorac Soc20063429329816738192

- JohnstonIDPrescottRJChalmersJCRuddRMBritish Thoracic Society study of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis: current presentation and initial management. Fibrosing Alveolitis Subcommittee of the Research Committee of the British Thoracic SocietyThorax199752138449039238

- JohnstonIBrittonJKinnearWLoganRRising mortality from cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitisBMJ19903016759101710212249048

- ArakawaHJohkohTHonmaKChronic interstitial pneumonia in silicosis and mix-dust pneumoconiosis: its prevalence and comparison of CT findings with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisChest200713161870187617400659

- CopleySJWellsAUSivakumaranPAsbestosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: comparison of thin-section CT featuresRadiology2003229373173614576443

- KitamuraHIchinoseSHosoyaTInhalation of inorganic particles as a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis – elemental microanalysis of pulmonary lymph nodes obtained at autopsy casesPathol Res Pract2007203857558517590529

- ScottJJohnstonIBrittonJWhat causes cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis? A case-control study of environmental exposure to dustBMJ1990301101510172249047

- IwaiKMoriTYamadaNYamaguchiMHosodaYIdiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Epidemiologic approaches to occupational exposureAm J Respir Crit Care Med199415036706758087336

- HubbardRLewisSRichardsKJohnstonIBrittonJOccupational exposure to metal or wood dust and aetiology of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitisLancet199634789972842898569361

- MullenJHodgsonMDeGraffAGodarTCase-control study of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and environmental exposuresJ Occup Environ Med19984043633679571528

- BaumgartnerKBSametJMCoultasDBOccupational and environmental risk factors for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a multicenter case-control study. Collaborating CentersAm J Epidemiol2000152430731510968375

- MiyakeYSasakiSYokoyamaTOccupational and environmental factors and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in JapanAnn Occup Hyg200549325926515640309

- BaumgartnerKBSametJMStidleyCAColbyTVWaldronJACigarette smoking: a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisAm J Respir Crit Care Med199715512422489001319

- SteeleMPSpeerMCLoydJEClinical and pathologic features of familial interstitial pneumoniaAm J Respir Crit Care Med200517291146115216109978

- HubbardRCooperMAntoniakMRisk of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in metal workersLancet2000355920246646710841131

- GustafsonTDahlman-HöglundANilssonKStrömKTornlingGTorénKOccupational exposure and severe pulmonary fibrosisRespir Med2007101102207221217628464

- PinheiroGAAntaoVCWoodJMWassellJTOccupational risks for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis mortality in the United StatesInt J Occup Environ Health200814211712318507288

- García-SanchoCBuendía-RoldánIFernández-PlataMRFamilial pulmonary fibrosis is the strongest risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisRespir Med2011105121902190721917441

- AwadallaNJHegazyAElmetwallyRAWahbyIOccupational and environmental risk factors for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Egypt: a multicenter case-control studyInt J Occup Environ Med20123310711623022860

- LeeJSCollardHRRaghuGDoes chronic microaspiration cause idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis?Am J Med2010123430431120362747

- TobinRWPopeCEPellegriniCAEmondMJSilleryJRaghuGIncreased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981586180418089847271

- RaghuGFreudenbergerTDYangSHigh prevalence of abnormal acid gastro-oesophageal reflux in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisEur Respir J200627113614216387946

- PattiMGTedescoPGoldenJIdiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: how often is it really idiopathic?J Gastrointest Surg20059810531058 discussion 1056–105816269375

- GribbinJHubbardRSmithCRole of diabetes mellitus and gastrooesophageal reflux in the aetiology of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisRespir Med2009103692793119058956

- LeeJSRyuJHElickerBMGastroesophageal reflux therapy is associated with longer survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011184121390139421700909

- LeeJSCollardHRAnstromKJAnti-acid treatment and disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an analysis of data from three randomized controlled trialsLancet Respir Med201315369376

- DevineMSGarciaCKGenetic interstitial lung diseaseClin Chest Med20123319511022365249

- LeeHLRyuJHWittmerMHFamilial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: clinical features and outcomeChest200512762034204115947317

- ArmaniosMYChenJJCoganJDTelomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisN Engl J Med2007356131317132617392301

- TsakiriKDCronkhiteJTKuanPJAdult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomeraseProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2007104187552755717460043

- NogeeLMDunbarAE3rdWertSEAskinFHamvasAWhitsettJAA mutation in the surfactant protein C gene associated with familial interstitial lung diseaseN Engl J Med2001344857357911207353

- ThomasAQLaneKPhillipsJHeterozygosity for a surfactant protein C gene mutation associated with usual interstitial pneumonitis and cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis in one kindredAm J Respir Crit Care Med200216591322132811991887

- van MoorselCHvan OosterhoutMFBarloNPSurfactant protein C mutations are the basis of a significant portion of adult familial pulmonary fibrosis in a dutch cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182111419142520656946

- WangYKuanPJXingCGenetic defects in surfactant protein A2 are associated with pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancerAm J Hum Genet2009841525919100526

- HodgsonUPulkkinenVDixonMELMOD2 is a candidate gene for familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisAm J Hum Genet200679114915416773575

- MushirodaTWattanapokayakitSTakahashiAPirfenidone Clinical Study GroupA genome-wide association study identifies an association of a common variant in TERT with susceptibility to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisJ Med Genet2008451065465618835860

- CronkhiteJTXingCRaghuGTelomere shortening in familial and sporadic pulmonary fibrosisAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008178772973718635888

- Diaz de LeonACronkhiteJTKatzensteinALTelomere lengths, pulmonary fibrosis and telomerase (TERT) mutationsPLoS One201055e1068020502709

- SeiboldMAWiseALSpeerMCA common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosisN Engl J Med2011364161503151221506741

- ZhangYNothIGarciaJGKaminskiNA variant in the promoter of MUC5B and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisN Engl J Med2011364161576157721506748

- PeljtoALZhangYFingerlinTEAssociation between the MUC5B promoter polymorphism and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisJAMA2013309212232223923695349

- FingerlinTEMurphyEZhangWGenome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pulmonary fibrosisNat Genet201345661362023583980

- NothIZhangYMaSFGenetic variants associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility and mortality: a genomewide association studyLancet Respir Med201314309317

- AlmagroPCalboEOchoa de EchagüenAMortality after hospitalization for COPDChest200212151441144812006426

- MartinezFJSafrinSWeyckerDIPF Study GroupThe clinical course of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisAnn Intern Med200514212 Pt 196396715968010

- SongJWHongSBLimCMKohYKimDSAcute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: incidence, risk factors and outcomeEur Respir J201137235636320595144

- du BoisRMWeyckerDAlberaCAscertainment of individual risk of mortality for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011184445946621616999

- CollardHRMooreBBFlahertyKRIdiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network InvestigatorsAcute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176763664317585107

- NavaratnamVFogartyAWGlendeningRMcKeeverTHubbardRBThe increasing secondary care burden of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: hospital admission trends in England from 1998 to 2010Chest201314341078108423188187

- CollardHRWardAJLanesSCortney HayfingerDRosenbergDMHunscheEBurden of illness in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisJ Med Econ201215582983522455577

- HubbardRJohnstonICoultasDBBrittonJMortality rates from cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in seven countriesThorax19965177117168882078

- SwigrisJJOlsonALHuieTJEthnic and racial differences in the presence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis at deathRespir Med2012106458859322296740

- HowladerNNooneAMKrapchoMSEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010 [webpage on the Internet]Bethesda, MDNational Cancer Institute2012 [updated June 14, 2013]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/, 2013Accessed August 16, 2013