Abstract

Background

Extrahepatic metastases have important implications in the clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The purpose of this study was to validate tumor staging parameters and serum AFP as risk factors of HCC metastasis.

Patients and methods

In this retrospective case–control study, patients with a new diagnosis of HCC (N=236), median age 57 years (range 28–89 years), and male-to-female ratio of 183/53 were divided into a “no-met” group (N=101) without extrahepatic metastasis or a “met” group with extrahepatic metastases (N=135). Metastasis risk factors based on tumor staging parameters (size, number, infiltration, and vascular invasion) and serum AFP level were calculated as odds ratio (OR). Sensitivities of the risk factors as metastasis screening tests were also calculated.

Results

AFP >400 μg/mL, index tumor size >5 cm, and vascular invasion individually had strong association with metastasis, with OR (95% confidence interval) of 11.5 (5.9–22.1), 17.7 (9.0–34.8), and 18.9 (8.2–43.9), respectively, but with moderate sensitivities as metastasis screening tests, with 71.9% (65.7–77.3), 75.6% (69.6–80.7), and 58.5% (52.1–64.7), respectively. Composite multiparametric criteria, eg, a logical union of 1) tumor size outside of Milan criteria, 2) AFP threshold >35 μg/mL, and 3) vascular invasion, had excellent OR up to 55.6 (13.0–237.1) with screening sensitivity 98.5% (95.8–99.6).

Conclusion

Serum AFP, tumor size, and vascular invasion are strongly associated with extrahepatic metastasis of HCC, especially when combined into a multiparametric metastasis prediction criterion.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is currently eighth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the USACitation1 and the fastest growing cancer in mortality.Citation2 Treatment recommendation depends on the patient’s clinical status (eg, liver function and performance status) and tumor stage.Citation3,Citation4 Patients with advanced-stage HCC, defined by the presence of vascular invasion and/or extrahepatic metastasis, are generally not considered candidates for curative treatment and are usually treated with systemic or palliative therapy. The prognosis of advanced-stage HCC is poor with median survival <1 year, in contrast to the ~70% 5-year survival of early-stage HCC.Citation5–Citation7

Extrahepatic metastasis (“metastasis” hereafter) occurs in one-third of patients with HCC,Citation8,Citation9 with the most common sites being lung, lymph nodes, bone, and adrenal glands.Citation10,Citation11 Metastases have important management implications, as locoregional therapies (eg, ablation, resection, and liver transplantation) are no longer effective controlling extrahepatic disease.Citation4,Citation5,Citation12,Citation13 Metastasis is also an independent predictor of poor survival.Citation14–Citation17 Therefore, it is crucial to determine the presence of metastasis at the time of initial HCC diagnosis, as initiation of appropriate therapy will determine survival.Citation11 However, exhaustive metastasis workup, which may include chest CT and bone scintigraphy, may be costly, time consuming, and unnecessary for those with low risk of metastasis.

Several noninvasive prognostic parameters of HCC have been proposed, including tumor size and serum AFP levels. Tumor size is an independent predictor of HCC progression, metastasis development, and overall survival.Citation10,Citation18–Citation20 High levels of AFP are independently associated with metastasis risk and poorer prognosis.Citation21–Citation23 Other parameters, such as vascular invasion and the number of tumors, also have survival implications.Citation23,Citation24 Accordingly, these parameters are integral part of various HCC staging systems.Citation12,Citation25–Citation30 To our knowledge, however, no specific criteria have been proposed for HCC metastasis risk stratification.

We hypothesize that the tumor staging parameters (eg, tumor size, number, infiltration, vascular invasion, and AFP) are associated with synchronous or metachronous metastasis in patients with HCC. The purpose of this study was to validate the tumor staging parameters, either as single-parametric criteria or as multi-parametric criteria, as risk factors of HCC metastasis. If validated, such criteria may allow rapid metastasis risk stratification at the time of diagnostic imaging and facilitate timely management decisions including the need for comprehensive metastasis workup.

Patients and methods

Study design and patient population

This retrospective case–control study at a tertiary-care public hospital was approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Investigational Review Board. Data were de-identified in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The need to obtain informed consent was waived. A review of an HCC clinic database was conducted to identify 457 consecutive patients with a new diagnosis of HCC between January 2005 and December 2011. HCC diagnosis was made either by direct tissue sampling or dynamic contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging (CT or MRI) per routine clinical care, interpreted by staff pathologists and radiologists, respectively. Two authors (AGS and ACY) adjudicated each case to confirm that it met diagnostic criteria by histology or the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease.Citation31 Routine evaluation of metastatic disease included chest X-ray and abdominal-pelvic CT (if not already performed). Additional imaging, such as chest CT and bone scan, was performed at the discretion of the treating physician.

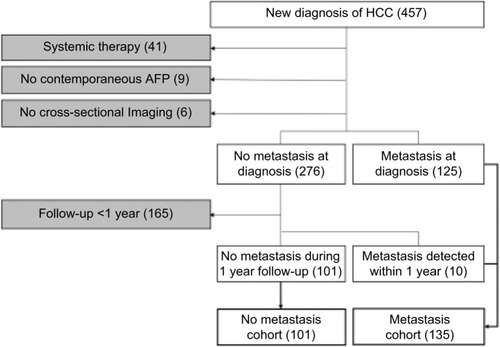

By chart review, patients were divided into the following two cohorts: 1) “no-met” cohort comprised patients without documented metastasis at the time of HCC diagnosis and during the first 12-month follow-up period from the initial diagnosis and 2) “met” cohort with documented metastasis at the time of initial diagnosis or detected during the first 12-month follow-up. A single index imaging study (CT or MRI) was selected for each patient. For those in the no-met group, the index study was the initial imaging examination leading to the HCC diagnosis. For those in the met group, the index imaging study was the pretreatment imaging examination closest to the time of metastasis diagnosis. Patients were excluded from the study if the image/clinical data were incomplete, or determination of the HCC metastasis status was compromised: 1) no documented metastasis but follow-up period <12 months; 2) no available pretreatment CT or MRI; 3) systemic HCC treatment during the follow-up period; 4) index CT/MRI images not available; 5) no contemporaneous pretreatment serum AFP, defined as <3 months of the index CT/MRI; and 6) history of any other cancers. The inclusion–exclusion criteria and the number of patients are graphically summarized in .

Data collection

For each patient, the index study’s images and its radiology report were reviewed. An axial image series that best depicted the tumor boundary was selected. The size of the dominant (index) tumor, either meeting the AASLD imaging criteria or biopsy proven, was measured as maximum axial diameter. Other nonindex tumors were measured, if they met the imaging criteria or had similar imaging features as the biopsy-proven index tumor. For diffuse infiltrative HCC, its size was coded as 99 cm due to difficulty in delineating the tumor boundary. Presence of vascular invasion (ie, involving either portal vein or hepatic vein) and infiltrative morphology were determined based on the official radiology report, in order to maintain consistency with the patient’s clinical management decisions.

The AFP level (μg/mL) and other demographic and clinical data including the age, sex, and Child-Turcotte-Pugh stage were recorded. Etiology of liver disease, including hepatitis C (positive serum antibody or RNA), hepatitis B (positive surface antigen), alcohol-related liver disease (alcohol intake >40 g/day for ≥10 years), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (negative work-up for other etiologies in the presence of the metabolic syndrome), and others/unknown, was noted.

A database was constructed using Microsoft Excel (Micro-soft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), which recorded tumor size, number, AFP, infiltration, and vascular invasion status, as well as the metastasis status (met vs no-met).

Metastasis risk criteria

Various staging parameters were considered as candidate metastasis risk factors and included AFP, tumor size, number, vascular invasion, and infiltrative morphology. These parameters were primarily derived from the following HCC staging systems: American Joint Commission on Cancer TNM system,Citation25 Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer system,Citation26 Cancer of the Liver Italian Program score,Citation27 and Chinese University Prognostic Index.Citation28 Although not strictly a staging system, the Milan criteria for liver transplant eligibilityCitation12 was also considered. Okuda et alCitation29 and Japan integrated staging scoreCitation30 were not considered separately, as the former did not include absolute size threshold and the latter used the TNM system for local staging. Although infiltrative morphology is not a part of any existing staging system, its metastasis risk was evaluated as it is associated with poor prognosis.Citation32,Citation33 The continuous variables (ie, AFP, index tumor size, and number of tumors) were stratified into discrete intervals (ie, interval data) according to the threshold values used in different staging systems as follows: AFP intervals 0–35, 35–400, and >400 μg/mL; index tumor size 0–3, 3–5, and >5 cm; and number of tumors 1, 2–3, and >3. Bivariate variables (vascular invasion and infiltrative morphology) were treated as categorical data.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R Version 3.3.1.Citation34 Summary statistics was calculated for demographic and clinical data, and the differences between the no-met and met cohorts were assessed using Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data and chi-square test for categorical data. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify statistically significant independent risk factors of metastasis. Rather than constructing a computationally demanding regression model, however, we considered a series of simple single- or multi-parametric criteria based on previously proposed threshold values. This approach is conceptually analogous to the Milan criteria,Citation12 which incorporates several parameters (tumor size, number, vascular invasion, and extrahepatic metastasis) into a single decision-rule using logical (union or intersection) operations. For each single- and multiparametric risk criteria, the association with metastasis was assessed by constructing the standard 2×2 contingency table and calculating the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Treating the risk criteria as a diagnostic test, the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and positive and negative predictive values were also calculated with their respective 95% CIs. The metastasis sensitivity between the single- and multiparametric criteria was compared using exact binomial test using R’s Diagnostic Test Comparison for Paired Study Design package (DTCom-Pair). P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant, after Benjamini–Hotchberg adjustment for multiple testing when appropriate.Citation35

Results

Patient population

The summary statistics of the study population (n=236) is summarized in , including the demographics, clinical data, and the tumor staging parameters. There was no significant difference in the patient age, sex, race, or liver disease etiology between the met and no-met cohorts. Patients with metastases tended to have more advanced cirrhosis (CPT stage B or C). All tumor staging parameters were significantly worse in the met cohort than in the no-met cohort, with greater AFP values and index tumor size, as well as multifocal disease, vascular invasion, and infiltrative tumor being more frequent. As expected, liver-directed HCC treatment was more common in the no-met cohort.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical data

Single-parametric criteria

The metastasis risk of each staging parameter is summarized in . All staging parameters were associated with metastasis with variable strength, with ORs ranging 2.9–18.9. Multifocality had the weakest and vascular invasion had the strongest association with metastasis. The criteria with greatest sensitivity for extrahepatic metastasis were index tumor size >3 cm (91.9%), Milan size criteria (85.9%), and AFP >35 μg/mL (82.2%). Criteria with greatest specificities were infiltrative tumor (98.0%), number of tumors >3 (95.0%), and vascular invasion (93.1%).

Table 2 Single-parametric criteria for metastasis

Logistic regression

Multivariate logistic regression results are summarized in . Milan size criteria were excluded from this analysis for its obvious correlation (by design) with tumor size and number. After correction for covariates, the following risk factors were independently associated with metastasis: AFP level, index tumor size, and presence of vascular invasion, all with adjusted P-values <0.05. No significance was detected for the number of tumor nodules and infiltrative morphology, after correcting for effects of AFP, tumor size, and vascular invasion.

Table 3 Tumor staging parameters and multivariate logistic regression

Multiparametric criteria

Of all possible logical combination of the independent risk factors (AFP, tumor size, and vascular invasion), only those that would improve sensitivity by “union” operations (to be used as metastasis screening test) were analyzed and results are shown in . Other logical combinations of risk factors, or other choices of threshold values and ranges, were not exhaustively considered to control the total number of simultaneous tests and associated penalty on the adjusted P-values. All combination criteria of AFP, size, and vascular invasion performed well with high sensitivities ranging from 86.7 to 98.5% for the detection of extrahepatic metastasis, with variable specificities and ORs. Multiparametric criteria including “Milan size or vascular invasion or AFP >35 μg/mL” had the highest sensitivity and OR of 98.5% and 55.6, respectively. The sensitivity of this multiparametric criteria was significantly better (P<0.001) than those of Milan size criteria, vascular invasion, or AFP >35 μg/mL alone as single-parametric criteria. Therefore, for patients determined to be within the Milan criteria based on imaging, the presence of extrahepatic metastatic disease is virtually excluded if AFP is also <35 μg/mL.

Table 4 Multiparametric criteria for metastasis

Comparison of criteria

The exact binomial test P-values for the differences in diagnostic sensitivity between the single-, two-, and three-parametric criteria are shown in . Depending on the tumor size parameter (>3 cm, >5 cm, or Milan size criteria), two-parametric criteria with combination of size parameter and either AFP >35 μg/mL or vascular invasion performed significantly better, and three-parametric criteria with combination of all size parameter, AFP >35 μg/mL, and vascular invasion performed significantly better than two-parametric criteria.

Table 5 Pairwise sensitivity comparison P-values between single-, two-, and three-parametric criteria

Discussion

In patients with new diagnosis of HCC, extrahepatic metastasis can profoundly impact treatment options and prognosis. Determination of metastasis risk using readily available imaging and serum AFP data may facilitate timely management decision-making, including the need for exhaustive metastasis workup. Furthermore, correct risk stratification of these patients may help avoid unnecessary morbidity and cost associated to loco-regional therapy. The purpose of this retrospective study in patients with new diagnosis of HCC was to validate the association between tumor staging parameters and synchronous/metachronous metastases, ultimately to enable rapid metastasis risk stratification based on imaging findings in conjunction with AFP.

Among the staging parameters in existing HCC staging systems, we found that index tumor size, vascular invasion, and AFP are independently associated with metastasis. Logical combinations of these parameters tended to be more strongly associated with metastases, often with significantly higher sensitivity for metastasis detection. In particular, the combination of Milan size criteria, vascular invasion, and AFP >35 μg/ml had the highest OR, sensitivity, and negative predictive values; in those patients in whom these criteria were simultaneously negative, metastasis was exceedingly rare.

The current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN, Version 2.2016) recommendation for confirmed HCC cases includes a chest CT and optional whole-body bone scintigraphy for metastatic workup.Citation36 Utility of whole-body PET imaging has been investigated,Citation37,Citation38 but its use as routine metastasis workup tool remains controversial. Up to 26/109 (24%) of our patients in the met cohort received loco-regional therapy, illustrating the difficulty of predicting extrahepatic metastasis at initial diagnosis with current staging approaches. Our study suggests that only a subset of patients with HCC is higher risk for metastasis who may require formal metastasis workup. Metastasis risk may be easily assessed based multiphasic liver CT or MRI findings in conjunction with serum AFP. In low-risk patients, it may be reasonable to refer immediately to liver-directed therapy, thereby shortening time to therapy and saving cost of additional imaging studies. In our study population, for example, the total cost saving would have been $21,000 in MEDICARE US dollars (or ~$90/patient), assuming the standard metastasis workup consisting of chest CT without contrast and whole body bone scan. Patients otherwise not meeting the low-risk criteria may benefit from comprehensive metastasis workup, and any extrahepatic abnormality found on imaging should be scrutinized with high suspicion of metastatic disease, especially those with high AFP >400 μg/mL, vascular invasion, multifocal, or infiltrative tumor(s), due to their moderate to high specificity for metastases.

Due to retrospective design, this study has several limitations. First, patient assignment into the no-met cohort was based on 12-month metastasis-free survival. This requirement was necessary because patients did not undergo uniform metastasis workup; the decision to obtain chest CT, bone scintigraphy, or PET in addition to routine chest radiograph was made at the discretion of the treatment provider, as per NCCN guideline at the time of their clinical care.Citation39 As this may have led to under-detection of subclinical metastases at initial diagnosis (ie, verification bias), we extended 12 months of clinical and/or imaging observation to allow initially undetected metastasis to declare itself over time. However, this requirement resulted in exclusion of ~1/3 of the potentially eligible patients who were lost during follow-up. Therefore, patients with very aggressive tumors or decompensated cirrhosis may have been underrepresented, as they were not likely to have survived long enough to meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Second, the potential therapy effect on metastasis development and detection could not be completely addressed. Patients already receiving systemic therapy at the time of diagnosis were excluded to prevent the confounding effect of systemic therapy on metastases. Majority of the no-met cohort and minority of the met cohort underwent liver-directed therapy. While complete response after such loco-regional therapy likely would not affect the evolution of extrahepatic metastases, partial, stable, or progressive disease could potentially pose additional risk of subsequent metastasis development. However, we believe that this was only a minor concern, since the majority of the met cohort had metastatic disease before initiation of therapy (125 out of 135 in met cohorts), and the possible confounding effect by treatment outcome is expected to be small. This study did not investigate cirrhosis as a risk factor of metastasis. The data on cirrhosis were incomplete, because determination of the cirrhosis status using a reference standard method (random liver biopsy; no serum markers or elastography techniques were available at the time of this study) was often not needed for clinical care. The HCC patient population at this public safety-net hospital has been overwhelmingly (>95%) those with known or suspected cirrhosis, and therefore, this population would not have allowed meaningful sub-analysis, even if the cirrhosis data were available. Finally, this study was conducted in a public safety-net hospital in a large metropolitan area, where patients could present with more advanced HCC in theory compared to insured population undergoing routine HCC surveillance.Citation40,Citation41 The rate of metastatic disease in this population, however, was similar to previous reports.Citation8,Citation9 Also, estimates of the OR, sensitivity, and specificity are independent of disease prevalence and hence our results may be generalizable to other patient populations. Our population was composed entirely of cirrhotic patients, most due to chronic hepatitis C infection; this may influence the frequency of metastasis and AFP threshold level.Citation42–Citation45 Due to these limitations, the metastasis screening criteria need to be further validated prospectively in an independently sampled population.

Conclusion

This retrospective study validated that tumor staging parameters are associated with metastasis risk in patients with new diagnosis of HCC. Patients with low metastasis risk may be identified based on AFP, tumor size, and absence of vascular invasion. In these patients, comprehensive metastasis workup may not be needed, thereby facilitating timely delivery of treatment and eliminating cost for further diagnostic imaging studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted with support from the Center for Translational Medicine, NIH/NCATS grant number UL1TR001105, and NIH/NCATS grant number KL2TR001103. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Center for Translational Medicine, UT Southwestern Medical Center, and its affiliated academic and health care centers, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure

AGS is on the Speakers’ Bureau and a consultant for Bayer. ACY is on the Speakers’ Bureau for Bayer and received research funding from Novartis, Merck, and Peregrine. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group [webpage on the Internet]United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2012 Incidence and Mortality Web-based ReportU.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute2015 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/uscsAccessed September 25, 2017

- RyersonABEhemanCRAltekruseSFAnnual report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2012, featuring the increasing incidence of liver cancerCancer201612291312133726959385

- BruixJShermanMLlovetJMClinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the LiverJ Hepatol200135342143011592607

- BruixJShermanMAmerican Association for the Study of Liver DiseasesManagement of hepatocellular carcinoma: an updateHepatology20115331020102221374666

- El-SeragHBMarreroJARudolphLReddyKRDiagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinomaGastroenterology200813461752176318471552

- PadhyaKTMarreroJASingalAGRecent advances in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinomaCurr Opin Gastroenterol201329328529223507917

- AltekruseSFMcGlynnKAReichmanMEHepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005J Clin Oncol20092791485149119224838

- NatsuizakaMOmuraTAkaikeTClinical features of hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic metastasesJ Gastroenterol Hepatol200520111781178716246200

- UchinoKTateishiRShiinaSHepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic metastasis: clinical features and prognostic factorsCancer2011117194475448321437884

- YooDJKimKMJinYJClinical outcome of 251 patients with extrahepatic metastasis at initial diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: does transarterial chemoembolization improve survival in these patients?J Gastroenterol Hepatol201126114515421175808

- KatyalSOliverJH3rdPetersonMSFerrisJVCarrBSBaronRLExtrahepatic metastases of hepatocellular carcinomaRadiology2000216369870310966697

- MazzaferroVRegaliaEDociRLiver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosisN Engl J Med1996334116936998594428

- SchwartzMLiver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinomaGastroenterology20041275 Suppl 1S268S27615508093

- SalaMFornerAVarelaMBruixJPrognostic prediction in patients with hepatocellular carcinomaSemin Liver Dis200525217118015918146

- ChlebowskiRTTongMWeissmanJHepatocellular carcinoma. Diagnostic and prognostic features in North American patientsCancer19845312270127066326991

- CalvetXBruixJGinesPPrognostic factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in the west: a multivariate analysis in 206 patientsHepatology1990124 pt 17537602170267

- LlovetJMBustamanteJCastellsANatural history of untreated nonsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma: rationale for the design and evaluation of therapeutic trialsHepatology199929162679862851

- LiJYanZLGongRYIndependent factors and predictive score for extrahepatic metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma following curative hepatectomyOncologist201217796396922653882

- QinLXTangZYThe prognostic significance of clinical and pathological features in hepatocellular carcinomaWorld J Gastroenterol20028219319911925590

- LiuCXiaoGQYanLNValue of alpha-fetoprotein in association with clinicopathological features of hepatocellular carcinomaWorld J Gastroenterol201319111811181923555170

- FarinatiFMarinoDDe GiorgioMDiagnostic and prognostic role of alpha-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma: both or neither?Am J Gastroenterol2006101352453216542289

- TangkijvanichPAnukulkarnkusolNSuwangoolPClinical characteristics and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis based on serum alpha-fetoprotein levelsJ Clin Gastroenterol200031430230811129271

- NomuraFOhnishiKTanabeYClinical features and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma with reference to serum alpha-fetoprotein levels. Analysis of 606 patientsCancer1989648170017072477133

- JunLZhenlinYRenyanGIndependent factors and predictive score for extrahepatic metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma following curative hepatectomyOncologist201217796396922653882

- EdgeSBAmerican Joint Committee on CancerAmerican Cancer SocietyAJCC Cancer Staging Handbook: from the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual7th edNew YorkSpringer2010xix718

- LlovetJMBruCBruixJPrognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classificationSemin Liver Dis199919332933810518312

- A new prognostic system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 435 patients: the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) investigatorsHepatology19982837517559731568

- LeungTWTangAMZeeBConstruction of the Chinese University Prognostic Index for hepatocellular carcinoma and comparison with the TNM staging system, the Okuda staging system, and the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program staging system: a study based on 926 patientsCancer20029461760176911920539

- OkudaKOhtsukiTObataHNatural history of hepatocellular carcinoma and prognosis in relation to treatment. Study of 850 patientsCancer19855649189282990661

- KudoMChungHHajiSValidation of a new prognostic staging system for hepatocellular carcinoma: the JIS score compared with the CLIP scoreHepatology20044061396140515565571

- BruixJShermanMPractice Guidelines CommitteeAmerican Association for the Study of Liver DiseasesManagement of hepatocellular carcinomaHepatology20054251208123616250051

- YoppACMokdadAZhuHInfiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma: natural history and comparison with multifocal, nodular hepatocellular carcinomaAnn Surg Oncol201522Suppl 3S1075S108226245845

- KneuertzPJDemirjianAFiroozmandADiffuse infiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma: assessment of presentation, treatment, and outcomesAnn Surg Oncol20121992897290722476754

- R Core TeamR: A Language and Environment for Statistical ComputingVienna, AustriaR Foundation for Statistical Computing2016

- BenjaminiYHochbergYControlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testingJ R Stat Soc B199557289300

- NCCN [webpage on the Internet]NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology2016 [cited August 22, 2016]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.aspAccessed September 25, 2017

- YoonKTKimJKKimDYRole of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in detecting extrahepatic metastasis in pretreatment staging of hepatocellular carcinomaOncology200772Suppl 110411018087190

- ChoYLeeDHLeeYBDoes 18F-FDG positron emission tomography-computed tomography have a role in initial staging of hepatocellular carcinoma?PLoS One201498e10567925153834

- BensonAB3rdAbramsTABen-JosefENCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: hepatobiliary cancersJ Natl Compr Canc Netw20097435039119406039

- SingalAGYoppAS SkinnerCPackerMLeeWMTiroJAUtilization of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance among American patients: a systematic reviewJ Gen Intern Med201227786186722215266

- SingalAGYoppACGuptaSFailure rates in the hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance processCancer Prev Res (Phila)2012591124113022846843

- CollierJShermanMScreening for hepatocellular carcinomaHepatology19982712732789425947

- Di BisceglieAMSterlingRKChungRTHALT-C Trial GroupSerum alpha-fetoprotein levels in patients with advanced hepatitis C: results from the HALT-C trialJ Hepatol200543343444116136646

- SterlingRKWrightECMorganTRFrequency of elevated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) biomarkers in patients with advanced hepatitis CAm J Gastroenterol20121071647421931376

- GopalPYoppACWaljeeAKFactors that affect accuracy of alpha-fetoprotein test in detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosisClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201412587087724095974