Abstract

Objective

Treatment decision-making in older patients with colorectal (CRC) or pancreatic cancer (PC) needs improvement. We introduced the EASYcare in Geriatric Onco-surgery (EASY-GO) intervention to optimize the shared decision-making (SDM) process among these patients.

Methods

The EASY-GO intervention comprised a working method with geriatric assessment and SDM training for surgeons. A non-equivalent control group design was used. Newly diagnosed CRC/PC patients aged ≥65 years were included. Primary patient-reported experiences were the quality of SDM (SDM-Q-9, range 0–100), involvement in decision-making (Visual Analog Scale for Involvement in the decision-making process [range 0–10]), satisfaction about decision-making (Visual Analog Scale for Satisfaction concerning the decision-making process [range 0–10]), and decisional regret (Decisional Regret Scale [DRS], range 0–100). Only for DRS, lower scores are better.

Results

A total of 71.4% of the involved consultants and 42.9% of the involved residents participated in the EASY-GO training. Only 4 trained surgeons consulted patients both before (n=19) and after (n=19) training and were consequently included in the analyses. All patient-reported experience measures showed a consistent but non-significant change in the direction of improved decision-making after training. According to surgeons, decisions were significantly more often made together with the patient after training (before, 38.9% vs after, 73.7%, p=0.04). Sub-analyses per diagnosis showed that patient experiences among older PC patients consistent and clinically relevant changed in the direction of improved decision-making after training (SDM-Q-9 +13.4 [95% CI −7.9; 34.6], VAS-I +0.27 [95% CI −1.1; 1.6], VAS-S +0.88 [95% CI −0.5; 2.2], DRS −10.3 [95% CI −27.8; 7.1]).

Conclusion

This pilot study strengthens the practical potential of the intervention’s concept among older surgical cancer patients.

Introduction

Major surgery in older cancer patients results in significant risks of complications that may jeopardize patients’ quality of life and functioning.Citation1,Citation2 Multi-morbidity and frailty are important elements in the surgical risk evaluation of these patients.Citation3 Colorectal (CRC) and pancreatic cancer (PC) resections in older patients are common examples of high-risk procedures, and decision-making in this context may still be improved considerably.Citation4–Citation6 For older CRC and PC patients and their families, it is important to understand what they can expect after surgery and how surgery may impact their daily life.Citation7 To adequately inform older patients, surgeons should integrate information on their physical and psychosocial problems, including the overall frailty.Citation7 However, this is a difficult task, and while preoperative geriatric assessment is recommended in many oncologic guidelines, it is usually limited to an anesthesiologic risk evaluation about the patient’s fitness for surgery.Citation8 Non-geriatric physicians are often overwhelmed by the complexity of geriatric patients.Citation9,Citation10 In addition, specific geriatric training in surgical curricula is minimal or lacking,Citation11 and there is room for improvement in implementing basic geriatrics.Citation12,Citation13 Moreover, to involve patients in decision-making and deliver patient-preferred care, shared decision-making (SDM) and shared goal-setting are widely recommended for surgical procedures in these frail patients where alternatives for a major operation are available.Citation3,Citation14,Citation15 Previous studies show that surgeons’ SDM skills can be optimizedCitation16,Citation17 specifically among older patients.Citation18,Citation19 We developed the EASYcare in Geriatric Onco-surgery (acronym EASY-GO) intervention, which is a multi-component intervention designed to optimize the SDM process among older CRC and PC patients. In this paper, we present the proof of concept of such a training intervention, based on a pilot study in surgical practice.

Methods

EASY-GO intervention

The EASY-GO intervention comprised an EASY-GO training for surgeons and nurse specialists focused on frailty and SDM after which the EASY-GO working method was implemented. According to this method, nurse specialists accomplished competencies in geriatric screening and surgeons applied SDM in their consultations.

EASY-GO training

The EASY-GO training for surgeons and nurse specialists lasted two sessions of two hours and two sessions of three hours, respectively. In the first session, participants were educated about frailty and geriatric screening during which quizzes, role plays, and case discussions were alternated. Knowledge about frailty and numbers of adverse outcomes in surgical elderly care was transferred by presentations. Active discussions took place using case descriptions. All case descriptions were derived from daily practice, e.g., baseline measurement. Discussion points included the following: is this patient frail and why? Since the EASYcare instrument (which comprised a brief standardized method of assessing the health and care needs perceptions of older people),Citation20 the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Geriatric Depression Scale 15 (GDS-15), and gait speed were part of the screening, these instruments including their interpretation were also explained during the first training day. The second training session focused on SDM. In a presentation, the theory of SDM and a model for clinical practice (based on the models of Elwyn,Citation14 Makoul,Citation15 and Van de Pol et al,Citation21 respectively) were discussed. Subsequently, the implementation of SDM and difficult conversations were practiced with an actor. Again, used case descriptions were derived from baseline measurement. At last, the EASY-GO working method was explained. The four trainers for all sessions were as follows: a GP specialized in SDM, elderly, and education; a geriatrician specialized in preoperative elderly care and education; and two geriatric nurse specialists. For surgeons, the training was offered on a voluntary basis.

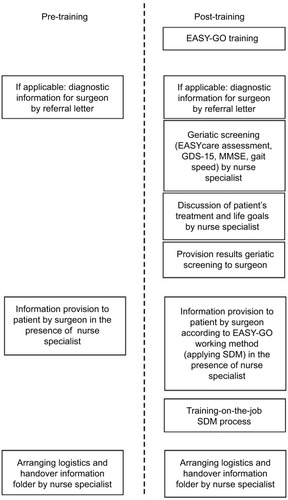

EASY-GO working method

After training, the EASY-GO working method was implemented with a few procedures added to usual care (). First, the nurse specialists performed 60 minutes of geriatric screening in all patients aged ≥65 years using the EASYcare instrument, MMSE, GDS-15, and gait speed. Since older CRC/PC patients and their physicians considered “obtaining an overall picture” and “taking into account frailty”, respectively, a key element in optimal decision-making,Citation7 we introduced the geriatric assessment as part of the EASY-GO intervention. In addition, patients’ goals in life and treatment preferences were discussed. In case of a lack of time or organizational issues, the screenings were accomplished by one of the researchers (NG). Afterward, results of the geriatric screening were provided to the surgeon before the surgeon welcomed the patient in the consultation room. Subsequently, trained surgeons applied SDM in the consultations taking into account the personal context of the patient. In general, treatment options for patients with CRC and PC (depending on cancer stage) include surgery, (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy (frequently in the context of a clinical trial), and no treatment. Adherence to the intervention was stimulated by training-on-the-job performed by a geriatric specialist; the surgeons received feedback post-consultation about the SDM process, and nurse specialists received feed-back about the geriatric screening.

Study design

Our multi-component training intervention was implemented and evaluated as part of a practice-based pilot study. A non-equivalent control group design was used. Before the EASY-GO training took place, a baseline measurement was conducted. After training, a posttest was carried out within a new group of patients. The EASY-GO intervention was implemented in the regular care processes for CRC and PC patients. No selection was made which surgeon consulted the patient. To analyze the implementation of the EASY-GO intervention, a process evaluation was also conducted.

Setting and participants

Consecutive patients were included at the surgical department of the Radboud university medical center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Inclusion criteria were as follows:

Patients ≥65 years

Patients registered as new patient diagnosed with CRC or PC (for patients with CRC in some cases with localized metastases)

Patients initially considered for surgery (whereby it was allowed that patients with rectal cancer already had had neoadjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy).

All consultations were observed by one of the researchers (NG). All consultants, residents, and nurse specialists involved in the abdominal oncology care in the study’s time frame were included in the pilot study. Patients did not know whether their physician was trained or not.

Outcome measures and data collection

Effects of EASY-GO intervention

Primary outcomes were four patient-reported experience measures (PREMs): patient-reported level of SDM, patient involvement in decision-making, patient satisfaction about the decision-making process, and patient’s decisional regret. Secondary outcomes were two patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) on patient’s quality of life and quality of functioning. For the primary outcomes, patients filled in a questionnaire at home after the final consultation when the treatment decision was made (T0). This questionnaire included the nine-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9Citation22,Citation23) for the patient-reported level of SDM (scale 0–100, where 0 indicates the lowest possible level of SDM and 100 indicates the highest extent of SDM). Since the SDM-Q-9 consists of nine statements rated on a six-point scale, raw total scores (0–45) were multiplied by 20/9 to rescale the total range from 0 to 100. The questionnaire also included visual analog scale scores (VAS-scores; scale 0–10, where 10 indicates the best score) for the extent of involvement in decision-making (VAS-I) and patient satisfaction concerning the decision-making process (VAS-S). After three months, patients were again asked to fill in a questionnaire (T1) which concerned decisional regret (Decisional Regret Scale [DRS];Citation24 scale 0–100, where 0 indicates no decisional regret and 100 indicates high regret). For the secondary outcomes, patients filled in the Older Persons and Informal Caregivers Survey Minimum Dataset (TOPICS-MDS) questionnaire,Citation25 both at T0 and at T1 to measure the quality of life (EuroQol five dimensional scale [EQ5D]; scale −0.33–1.00, where 1 indicates the highest quality of life) and quality of functioning (KATZ index of independence in activities and instrumental activities in daily living [KATZ-15]; scale 0–15, whereby higher scores indicate more disabilities). In addition to the primary and secondary outcomes, patients were additionally asked about who made the decision (adjusted Control Preference Scale [aCPST0])Citation26,Citation27 at T0 and which role they preferred in decision-making in hindsight (adjusted Control Preference Scale [aCPST1]) at T1. In addition to patients, surgeons also filled in a short questionnaire immediately after the final consultation to determine patient involvement in decision-making (VAS-Idoc) and to determine who made the decision according to them (aCPSdoc).

To analyze the process of implementation of the EASY-GO intervention, the adherence to all intervention components was documented.

Data analysis

For our analyses, we only included surgeons who consulted patients both before and after implementation of the intervention to be able to analyze the change in their SDM skills. In addition, surgeons who did not participate in the EASY-GO training were excluded in the analyses to be able to evaluate the implementation of the complete EASY-GO intervention like the intended design. To compare baseline characteristics before and after implementation, Student’s t-test was used for continuous data, chi-square test was used to compare categorical data, and Fisher’s exact test was used in case of small numbers per category. Differences were considered statistically significant if the p-value was <0.05 (for two-tailed tests). For evaluating differences in primary and secondary outcomes before and after implementation of the intervention, a linear mixed model was used to account for clustering within individual surgeons. Sub-analyses were performed per diagnosis, CRC or PC. Change in PREMs was considered clinically relevant if the SDM-Q-9 score differed by ≥10, if the VAS-I and VAS-S scores differed by ≥1, and if the DRS score differed by ≥−10. ADL decline was considered clinically relevant if the KATZ-15 score differed by ≥1 points between T0 and T1. Change in quality of life was considered clinically relevant if the EQ5D score differed by ≥0.10 points. Data were analyzed using the statistical software program SPSS version 22. With respect to the process evaluation, the performed and adhered components of the EASY-GO intervention are presented as frequencies and percentages.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee (CMO Arnhem-Nijmegen, #2014-1400). All patients gave written and verbal informed consent to process their data.

Results

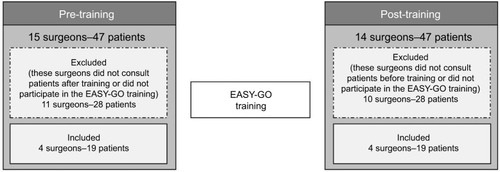

In total, 94 patients were included in the study’s time frame (January 2015–January 2016): 47 before and 47 after implementation of the EASY-GO intervention (). Twenty different surgeons were engaged with these 94 patients. In total, six consultants and five residents participated in the EASY-GO training. Only four trained surgeons consulted patients both before (n=19) and after (n=19) training and were consequently included in the analyses. All three nurse specialists completed the training to perform the geriatric screenings.

Figure 2 Flowchart that explains the number of surgeons and patients included in the study.

Characteristics of the included patients before and after training did not significantly differ (). PC patients were always seen by consultants, while CRC patients were also seen by residents.

Table 1 Patient characteristics before and after implementation of the EASY-GO intervention

Primary outcomes

All PREMs showed a change in the direction of improved decision-making after training, but the 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of the mean difference scores were wide (). Patient involvement as rated by surgeons also changed in the direction of improved decision-making. Before training, 13.3% of the patients mentioned that the decision was made by the doctor, 66.7% mentioned that the decision was made together with the doctor, and 20.0% mentioned that the decision was made by themselves or relatives. After training, these percentages were 20.0%, 73.3%, and 6.7%, respectively (p=0.54). According to surgeons, 55.6% of the surgeons before training mentioned that the decision was made by them, 38.9% mentioned that the decision was made together with the patient or relatives, and 5.6% mentioned that the decision was made by the patient. After training, surgeons mentioned significantly more often that the decision was made together with the patient (73.7%) and less often that the decision was made by them (15.8%) (p=0.04). A total of 10.5% mentioned that the decision was made by the patient and/or their relatives.

Table 2 Primary and secondary outcomes before and after implementation of the EASY-GO intervention

Secondary outcomes

In accordance with the actual phase of the patients’ treatment trajectories, quality of life and quality of functioning as secondary PROMs seemed to slightly worsen after three months both before and after training (). The difference in change in EQ5D scores before and after training was marginal (). The change in KATZ-15 scores seemed clinically relevant before training, where scores after training were mutually more comparable.

Sub-analyses per diagnosis

The quality of SDM and decisional regret among PC patients showed a clinically relevant change in the direction of improved decision-making after implementation (). The mean patient involvement score as rated by PC consultants significantly improved after training (VAS-Idoc: +1.23; 95% CI: 0.2; 2.2). Among CRC patients, only patient involvement showed a clinically relevant change in the direction of improved decision-making. Comparing the two diagnoses, PREMs were consistently better among PC patients after implementation (SDM-Q-9: +13.3 [95% CI: −3.8; 30.5]; VAS-I: +1.73 [95% CI: −0.3; 3.8]; VAS-S: +0.9 [95% CI: −1.0; 2.7]; DRS: −11.0 [95% CI: −38.9; 16.9]).

Table 3 Primary and secondary outcomes per diagnosis before and after implementation of the EASY-GO intervention

Quantitative process evaluation

Degree of implementation

In total, 71.4% of the involved consultants, 42.9% of the involved residents, and 100% of the nurse specialists participated in the EASY-GO training. After training, 18 patients (94.7%) received a geriatric screening as part of the EASY-GO working method. Only 16.7% of them were screened by nurse specialists. All others were screened by one of the researchers (NG). The geriatric screening results of 17 patients (94.4%) were provided to the consultant or resident. The total duration of consultations did not significantly increase after training ().

Discussion

We piloted a training for surgeons and nurse specialists concerning SDM and a geriatric screening in the regular care processes for older patients with CRC or PC of our surgical department. The promising results in this study support the practical potential of the intervention’s concept and its feasibility.

Though PREMs among trained surgeons showed a consistent change in the direction of improved decision-making, the wide confidence intervals of the mean difference scores suggest that significance could not be reached in our small sample size. Besides, the learning maximum was possibly not yet reached in our study since the ongoing training-on-the-job also belonged to the intervention’s effect and each trained surgeon only consulted a few patients in the short study period. The effect on PREMs might have been bigger when the training-on-the-job period was expanded. The consistent change in PREMs in the direction of improved decision-making among PC patients, who were all consulted by trained consultants after implementation, suggests that the EASY-GO intervention was appropriate for this target group. Also the more dedicated regular care procedures for PC patients with less varying physicians may have contributed. Regarding older CRC patients among whom PREMs did not consistently change in the direction of improved decision-making, differences in the number and duration of consultations and differences in future health perspective may have contributed.

Previous studies concerning the effectiveness of SDM training programs for professionals show equivocal effects.Citation28,Citation29 The quality of evidence regarding SDM training generally is low and in surgical care virtually non-existing. Training programs vary extensively and only a few are sufficiently evaluated.Citation29,Citation30 Nevertheless, there is consensus about the need to improve patients’ participation in decision-making and to implement SDM,Citation30–Citation32 whereby any kind of intervention that actively targets patients, physicians, or both is suggested to be better than none.Citation29 Among physicians, SDM training programs are associated with increased confidence in their own SDM and interaction competencies,Citation33 which correspond to our findings among trained PC surgeons. CRC surgeons, however, showed a clinically relevant change in patient involvement in the direction of worse decision-making after training. It is presumed that surgeons just realized after training what SDM is and thus whether they actually involve patients in decision-making. Because of the small total number of patients per surgeon, CRC surgeons could not develop their skills in practice.

Our pilot study has several strengths. Besides in older patients, we studied the effect of an SDM training in patients with PC or CRC, two cancer types with high perioperative morbidity and risk of decrease in quality of life and functioning.Citation34 The practice-based design of our study favors it being representative for other hospitals. In addition, the general content of the EASY-GO training and working method makes the intervention, after only small changes, for example regarding information provision, applicable for other diagnoses and departments. We used relevant patient-reported experiences to evaluate the EASY-GO intervention. Specifically in clinical trials concerning patient-centered care, experience measures compared to outcomes measures are of additional value as quality indicators for personalized medicine.Citation35–Citation37 Moreover, patients and relatives were blinded for the training status of their surgeon. After training, patients received a geriatric screening including discussion of patients’ life goals and treatment goals, which at least somewhat prepared patients for the consultation with their surgeon.Citation28,Citation29 Learning opportunities were optimal since our training was based on practice-based learningCitation13,Citation38 and comprised a short workshop including role plays with an actor and training-on-the-job.Citation39

The study also has relevant limitations. We used a pragmatic pilot study with different patient groups before and after training, which complicated the interpretation of the results and possibly have obscured the effect of the intervention. We excluded all surgeons who only consulted patients before or after training reducing the sample size. In addition, only about half of the surgeons were trained decreasing the likelihood to demonstrate a positive effect of the intervention. However, in this pilot study, we aimed to present proof of concept of a training intervention such as the EASY-GO intervention including its practical barriers in order to optimize future study designs. Therefore, we did not intend to achieve appropriate target enrollment for statistical significance. With a voluntary training, we expect that the most motivated surgeons in SDM participated. This may have reduced the positive effect of the training due to relatively good initial SDM performance.Citation33 Patients were seen by consultants or residents and PREMs were evaluated for different diagnoses, which both may have had an independent effect on the outcomes. Nevertheless, we found no significant differences in PREMs between consultants and residents at baseline and we additionally analyzed PREMs among PC patients who were all seen by trained consultants. Unclear is why CRC senior consultants as role models did not participate in the EASY-GO training. One reason may be an overestimation of their own SDM skills.Citation40 Alternatively, the inclusion of several colon cancer patients with a less rigorous impact of the surgical procedure on quality of life may have resulted in a non-recognized equipoise of treatment options and unrecognized added value of the intervention. Due to time limits and logistic issues, one of the researchers accomplished most geriatric screenings instead of the nurse specialists. However, the nurse specialist was always present during the consultation with the surgeon corresponding to regular care and the researcher accomplished only the geriatric screening which may have limited a potential bias effect. Besides, the geriatric screening for nurse specialists was time-consuming: we planned 60 minutes per patient. However, screenings went more quickly with increasing practical experience, which made the screening more doable and acceptable for clinical practice.

Because of the practical potential of the intervention’s concept and besides the limitations of our study design, we recommend to further investigate the effect of the EASY-GO intervention in a randomized controlled design on a larger scale using a mandatory training. Because of the promising results among PC patients, we recommend to start with this target group. Since the implementation of SDM and screening of the older patient’s context are connected with each other,Citation7 we advise to deliver both components simultaneously, for example, with help from nurse specialists. Ideally, it would also be investigated which component of the EASY-GO intervention can contribute to what extent. Expanding and repeating the training-on-the-job period is desirable to maximize the learning effect. Since the geriatric screening lasted 30 minutes per patient for nurse specialists, time- and cost-related investments should be explored, as well as possibilities for defrayment and the most optimal interdisciplinary collaboration.

Conclusion

Results of this pilot study strengthen the idea that (the implementation of) a SDM training such as the EASY-GO intervention may have potential benefit among older surgical cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- VerweijNMSchiphorstAHMaasHAColorectal cancer resections in the oldest old between 2011 and 2012 in the NetherlandsAnn Surg Oncol20162361875188226786093

- BrownSRMathewRKedingAMarshallHCBrownJMJayneDGThe impact of postoperative complications on long-term quality of life after curative colorectal cancer surgeryAnn Surg2014259591692324374539

- CooperZKoritsanszkyLACauleyCERecommendations for best communication practices to facilitate goal-concordant care for seriously Ill older patients with emergency surgical conditionsAnn Surg201626311626649587

- OkabayashiTShimaYIwataJIs a surgical approach justified for octogenarians with pancreatic carcinoma? Projecting surgical decision making for octogenarian patientsAm J Surg2016212589690227262755

- FitzsimmonsDGeorgeSPayneSJohnsonCDDifferences in perception of quality of life issues between health professionals and patients with pancreatic cancerPsychooncology19998213514310335557

- VerweijNMHamakerMEZimmermanDDThe impact of an ostomy on older colorectal cancer patients: a cross-sectional surveyInt J Colorectal Dis2017321899427722790

- GeessinkNHSchoonYvan HerkHCvan GoorHOlde RikkertMGKey elements of optimal treatment decision-making for surgeons and older patients with colorectal or pancreatic cancer: a qualitative studyPatient Educ Couns2017100347347928029569

- LevettDZEdwardsMGrocottMMythenMPreparing the patient for surgery to improve outcomesBest Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol201630214515727396803

- RuizMReskeTCefaluCEstradaJManagement of elderly and frail elderly cancer patients: the importance of comprehensive geriatrics assessment and the need for guidelinesAm J Med Sci20133461666923154654

- UgoliniGGhignoneFZattoniDVeroneseGMontroniIPersonalized surgical management of colorectal cancer in elderly populationWorld J Gastroenterol201420143762377724833841

- ShipwayDJPartridgeJSFoxtonCRDo surgical trainees believe they are adequately trained to manage the ageing population? A UK survey of knowledge and beliefs in surgical traineesJ Surg Educ201572464164725887505

- SchiphorstAHTen Bokkel HuininkDBreumelhofRBurgmansJPPronkAHamakerMEGeriatric consultation can aid in complex treatment decisions for elderly cancer patientsEur J Cancer Care (Engl)201625336537026211484

- van de PolMHFluitCRLagroJSlaatsYOlde RikkertMGLagro-JanssenALShared decision making with frail older patients: proposed teaching framework and practice recommendationsGerontol Geriatr Educ201738448249528027017

- ElwynShared decision making: a model for clinical practiceJ Gen Intern Med201227101361136722618581

- MakoulAn integrative model of shared decision making in medical encountersPatient Educ Couns200660330131216051459

- LevinsonWHudakPTriccoACA systematic review of surgeon-patient communication: strengths and opportunities for improvementPatient Educ Couns201393131723867446

- SnijdersHSKunnemanMBonsingBAPreoperative risk information and patient involvement in surgical treatment for rectal and sigmoid cancerColorectal Dis2014162O43O4924188458

- CooperZCourtwrightAKarlageAGawandeABlockSPitfalls in communication that lead to nonbeneficial emergency surgery in elderly patients with serious illness: description of the problem and elements of a solutionAnn Surg2014260694995724866541

- SteffensNMTucholkaJLNaboznyMJSchmickAEBraselKJSchwarzeMLEngaging patients, health care professionals, and community members to improve preoperative decision making for older adults facing high-risk surgeryJAMA Surg20161511093894527368074

- PhilipKEAlizadVOatesADevelopment of EASY-Care, for brief standardized assessment of the health and care needs of older people; with latest information about cross-national acceptabilityJ Am Med Dir Assoc2014151424624169306

- van de PolMHFluitCRLagroJSlaatsYHOlde RikkertMGLagro-JanssenALExpert and patient consensus on a dynamic model for shared decision-making in frail older patientsPatient Educ Couns20169961069107726763871

- KristonLSchollIHolzelLSimonDLohAHarterMThe 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9). Development and psychometric properties in a primary care samplePatient Educ Couns2010801949919879711

- Rodenburg-VandenbusscheSPieterseAHKroonenbergPMDutch translation and psychometric testing of the 9-Item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9) and Shared Decision Making Questionnaire-Physician Version (SDM-Q-Doc) in primary and secondary carePLoS One2015107e013215826151946

- BrehautJCO’ConnorAMWoodTJValidation of a decision regret scaleMed Decis Making200323428129212926578

- LutomskiJEBaarsMASchalkBWThe development of the Older Persons and Informal Caregivers Survey Minimum DataSet (TOPICS-MDS): a large-scale data sharing initiativePLoS One2013812e8167324324716

- DegnerLFSloanJAVenkateshPThe control preferences scaleCan J Nurs Res19972932143

- SinghJASloanJAAthertonPJPreferred roles in treatment decision making among patients with cancer: a pooled analysis of studies using the control preferences scaleAm J Manag Care201016968869620873956

- DwamenaFHolmes-RovnerMGauldenCMInterventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultationsCochrane Database Syst Rev201212CD00326723235595

- LegareFStaceyDTurcotteSInterventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionalsCochrane Database Syst Rev20149CD00673225222632

- DioufNTMenearMRobitailleHPainchaud GuerardGLegareFTraining health professionals in shared decision making: update of an international environmental scanPatient Educ Couns201699111753175827353259

- OchiengJBuwemboWMunabiIInformed consent in clinical practice: patients’ experiences and perspectives following surgeryBMC Res Notes2015876526653100

- BossEFMehtaNNagarajanNShared decision making and choice for elective surgical care: a systematic reviewOtolaryngol Head Neck Surg2016154340542026645531

- BieberCNicolaiJHartmannMTraining physicians in shared decision-making – who can be reached and what is achieved?Patient Educ Couns2009771485419403258

- SpertiCMolettaLPozzaGPancreatic resection in very elderly patients: a critical analysis of existing evidenceWorld J Gastrointest Oncol201791303628144397

- CalvertMBlazebyJAltmanDGRevickiDAMoherDBrundageMDReporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extensionJAMA2013309881482223443445

- BermanATRosenthalSAMoghanakiDWoodhouseKDMovsasBVapiwalaNFocusing on the “person” in personalized medicine: the future of patient-centered care in radiation oncologyJ Am Coll Radiol20161312 Pt B1571157827888944

- HuebnerJRoseCGeisslerJIntegrating cancer patients’ perspectives into treatment decisions and treatment evaluation using patient-reported outcomes – a concept paperEur J Cancer Care (Engl)201423217317923889081

- KolbDExperiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and DevelopmentEnglewood CliffsPrentice Hall19842038

- HeavenCCleggJMaguirePTransfer of communication skills training from workshop to workplace: the impact of clinical supervisionPatient Educ Couns200660331332516242900

- Tyler EllisCCharltonMEStitzenbergKBPatient-reported roles, preferences, and expectations regarding treatment of stage I rectal cancer in the cancer care outcomes research and surveillance consortiumDis Colon Rectum2016591090791527602921

- VerhageFIntelligence and Age in a Dutch SampleHuman Development19658238245