Abstract

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are relatively common mesenchymal tumors. They originate from the wall of hollow viscera and may be found in any part of the digestive tract. The prognosis of patients with stromal tumors depends on various risk factors, including size, location, presence of mitotic figures, and tumor rupture. Emergency surgery is often required for stromal tumors with hemorrhage. The current literature suggests that stromal tumor hemorrhage indicates poor prognosis. Although the optimal treatment options for hemorrhagic GISTs are based on surgical experience, there remains controversy with regard to optimum postoperative management as well as the classification of malignant potential. This article reviews the biological characteristics, diagnostic features, prognostic factors, treatment, and postoperative management of GISTs with hemorrhage.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are common mesenchymal tumors. They originate from the luminal wall and may occur in any part of the digestive tract. Most GISTs occur in the stomach (60%–70%) or the small intestine (25%–35%). The colon, rectum, appendix (5%), and esophagus (2%–3%) are relatively rare sites.Citation1,Citation2 They may even occur outside the digestive tract, including in the greater omentum, mesentery, and retroperitoneal sites.Citation3 The size of most stromal tumors is about 5 cm at diagnosis.Citation4 Approximately 70% of GIST patients are symptomatic. There are a wide variety of clinical manifestations, including rare presentations as part of the syndrome, known as Carneys triad: gastric stromal tumor, pulmonary chondroma, and paraganglioma. They are also seen in neurofibromatosis type 1.Citation5,Citation6 Stromal tumors of the small intestine often present as abdominal pain and hemorrhage of the digestive tract. Rectal stromal tumors may manifest as hematochezia and obstruction.Citation7 Gastrointestinal bleeding is a relatively common presentation.Citation8,Citation9 Prognosis varies by location.

Because of the interference of various factors and limitations of the research samples, the classification of malignant potential of GISTs and postoperative management remains controversial. Age and gender may be the prognostic factors: it has been reported that the prognosis of women aged <50 years is better than that of women aged >50 yearsCitation10 and that GISTs are more common in women aged 50–70 years.Citation11 This last study also suggests that obesity may be a protective factor for patients with stromal tumors.Citation12 The 2016.v2 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)Citation13 guidelines suggest that patients with high-risk factors for recurrence (tumor size >5 cm with large numbers of mitotic figures [>5/50 high-power field], tumor rupture, or recurrence risk >50%) should be treated with oral Gleevec postoperatively for least 36 months to reduce the risk of recurrence. However, there is controversy, as reported in , over the risk degrees for assessing malignant potential of GISTs.

Table 1 The different risk degrees for assessing malignant potential of GISTs

Some investigators believe that gastrointestinal bleeding is caused by tumor invasion of the mucosa layer, resulting in ulceration,Citation14 while tumor rupture occurs mostly in the serosa. Recently, many studies have reported that prognosis of GISTs with gastrointestinal bleeding is relatively poor compared with patients without bleeding. Recently, researchers have found that gastrointestinal bleeding may be an independent risk factor for recurrence.Citation15–Citation17 According to the 2012 edition of the Guidelines for the European Society of Oncology,Citation18 GISTs of different malignant potential levels require different postoperative treatment and management. Although the emergence of targeted drugs such as imatinib has improved prognosis of stromal tumors more than that of other malignant tumors, there is also an incidence of adverse outcomes that lead to tumor recurrence and metastasis due to irregular treatment.

Molecular classifications and clinicopathological features of GIST

The average age of patients diagnosed with stromal tumors is 60 years. There are no significant epidemiological differences with respect to gender, ethnicity, or location.Citation9,Citation14,Citation19 The prevailing hypothesis is that GISTs originate from the interstitial cells of Cajal in the muscularis propria and the myenteric plexus.Citation20 Cell morphologies are characterized as spindle cell (70%), epithelioid cell (20%), and mixed cell (10%).Citation21–Citation23 KIT, DOG1, and CD34 have been identified as important immunohistochemical markers for making the diagnosis.Citation24–Citation26 In addition, CD34 and CD117 are likely to occur in GISTs.Citation27 The expression of these markers plays an important role in regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, and apoptosis. CD117 is currently recognized as one of the most significant markers of immune expression in stromal tumors. Hirota and other investigators have found that most GISTs produce genetic mutations, mostly in c-KIT. Approximately 90% of GISTs are associated with mutations in c-KIT,Citation8 affecting the expression of exons 9, 11, 13, and 17.Citation28 These mutations lead to continuous activation of tyrosine kinases, leading to cell proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis. These are the targets of tyrosinase inhibitors, such as imatinib. The distribution proportion of these mutations is approximately as follows: exon 11 (57%–71%); exon 9 (10%–18%); exon 13 (1%–4%); and exon 17 (1%–4%).Citation24,Citation25,Citation29 The most frequent mutation in exon 11 is gene deletion, usually between codons 550 and 579, especially the codon 557–559.Citation4 However, in c-KIT-negative GISTs, another tyrosine kinase receptor, called platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA), has also been identified.Citation8,Citation30 Most PDGFRA mutations affect exon 18 and less commonly exons 12 and 14.Citation14,Citation31–Citation34 Overall, the PDGFRA gene mutation is estimated to account for 5%–10% of GISTs.Citation21,Citation32,Citation35 It has been documented that 80% of PDGFRA mutations occur in the stomach and omental tissue.Citation14

Approximately 10% of adult GISTs are not associated with KIT or PDGFRA mutations,Citation22,Citation36 while some stromal tumors do not harbor any known gene mutations. These are called “wild-type” tumors. These may arise from other pathogeneses, such as deficiency of succinate dehydrogenaseCitation37–Citation39 or BRAF mutations.Citation4

The pathological features of GISTs are closely related to prognosis. The Z90001 study by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group found that the tumor size, location, and mitotic figure number are the most important factors affecting recurrence-free survival, as opposed to type of gene mutation.Citation40 The classification of gene mutation often determines postoperative management and treatment, so it is important to improve gene analysis.

Common clinical manifestations and diagnostic features of GISTs

Clinical features

The clinical manifestations of GISTs are atypical and nonspecific, depending on tumor size, location, and other factors. The most common clinical presentations are gastrointestinal bleeding and abdominal discomfort. Gastrointestinal bleeding accounts for about 30%–40%, abdominal pain 20%–50%, obstruction 10%–30%, and asymptomatic GIST patients account for 20%.Citation8,Citation9,Citation41,Citation42 Rare manifestations include biliary obstruction, dysphagia, intussusception, and hypoglycemia.

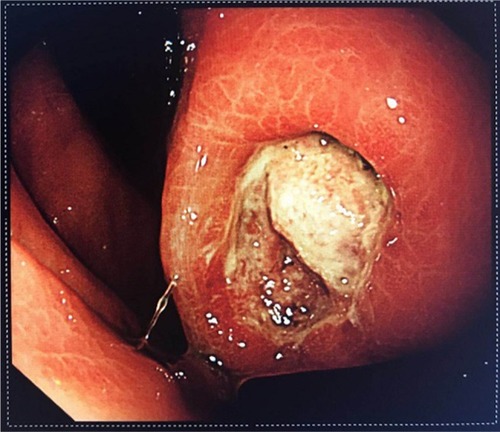

Gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common and the most dangerous complication, often necessitating emergency surgery. The risk of such surgery is significantly higher than that of elective surgery. GIST patients with chronic hemorrhage mainly present with anemia, emaciation, and melena. In cases of acute hemorrhage, the presentation may include peritonitis and shock. Spontaneous rupture of the tumor is rare in GISTs and often occurs in the gastrointestinal tract.Citation43 Most hemorrhagic stromal tumors are associated with intact tunica serosa. Mucosal ulceration or tumor invasion of nutrient vessels leads to bleeding. In , the tumor was ulcerated and bleeding was seen under endoscopy. Ulcers cause cancer-like umbilicated lesions. Some controversy remains as to whether these forms represent tumor rupture. Nevertheless, it has been mentioned in the literature that stromal tumors with hemorrhage may be independent risk factors for recurrence of stromal tumors.

The causes of gastrointestinal bleeding in GIST

The causes of intraluminal hemorrhage of GISTs may be related to mucosal and submucosal destruction by tumor growth, invasion of nutrient vessels leading to vascular rupture, tumor necrosis, and the joint action of digestive juices, gastrointestinal peristalsis, and fecal transmission. GISTs are relatively fragile and more vascularized, compared with other common gastrointestinal tumors. In general, by the time symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding appear, the tumor would already have attained a relatively large size.Citation44 Studies have shown that the proportion of stromal tumor bleeding in the small intestine is much greater than in the stomach.Citation16 This may be related to the size and space of the particular portion of the gastrointestinal tract.

Diagnostic features

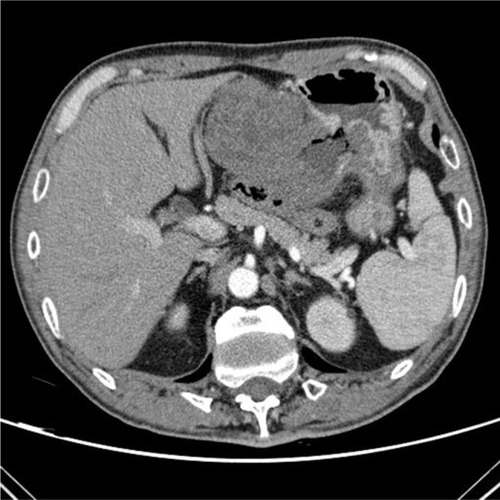

In the acute hemorrhagic phase, digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is often positive and has hemostatic effects.Citation45 However, DSA alone cannot distinguish benign from malignant tumors. Definitive diagnosis requires endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and pathological examination.Citation46 Some stromal tumors may have “air sign” on plain film as shown in , caused by internal bleeding, necrosis, or ulceration. There are few reported cases of bleeding outside the lumen in GISTs. Case reports suggest that trauma or external force may cause rupture and bleeding. The causes of GISTs bleeding are similar to those of other primary gastrointestinal malignant tumors; however, the proportion of GISTs that bleed is greater. Therefore, intestinal bleeding should raise the index of suspicion for GISTs. It is believed that the hemorrhage of stromal tumor is related to its pathological, immunohistochemical, or gene mutation type.

Figure 2 The enhanced-contrast CT image of a GIST with hemorrhage: the typical “air sign” is caused by hemorrhage and necrosis of the tumor.

Abbreviation: GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

Contrast-enhanced CT (ECT) is the most commonly used diagnostic modality for stromal tumors and is used as well for postoperative review and evaluation for recurrence and progression. EUS is also used to diagnose GISTs. By ultrasound, early tumor shows a hypoechoic mass. As the tumor grows, it replaces surrounding structures, forming cystic, necrotic, and bleeding areas. The sensitivity and specificity of EUS for diagnosis of stromal tumors in the stomach and colon are 98% and 64%, respectively.Citation47 However, the diagnostic efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided Trucut biopsy (EUS-TCB) and EUS-fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) are not very good. In addition, these procedures are complicated by pain, bleeding, and fever, among others. The complication rates are 3.3% for EUS-TCB and 8.1% for EUS-FNA.Citation48 Early stromal tumors rarely metastasize to lymph nodes; however, these tumors tend to be large and they may infiltrate neighboring organs. Unlike other sarcomas, GIST does not metastasize to the bone and lungs. The most common target organs of distant metastasis are liver, peritoneum, and greater omentum.Citation24,Citation25,Citation49 Therefore, TCB and FNA are not recommended if the patient is not being considered for conversion therapy, or if the clinician needs to differentiate GISTs from other tumors, for the following reasons: 1) stromal tumors are generally relatively easy to remove, 2) tumor rupture should be prevented in case of implantation metastasis, and 3) because of the presence of tumor capsule, it is difficult to get sufficient tissue to make a definite diagnosis using these modalities.Citation23 An MRI is useful mainly to analyze invasion by pelvic lesions and to evaluate for liver metastases. For other locations, enhanced CT is preferred. Compared with other tumors of digestive tract, PET is not useful in the evaluation of GISTs. It may be only helpful for the case of GISTs with liver metastasis.Citation50 However, the sensitivity and positive predictive value of PET-CT using 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose in stromal tumors are 86% and 98%, respectively. These rates are better than those of CT for the recurrence and metastasis of stromal tumors.Citation51

Treatments for GIST with gastrointestinal bleeding

Surgery is the treatment of choice for stromal tumors, whether there are symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding. Some investigators believe that surgery is indicated when GIST size is >2 cm, otherwise it can be managed expectantly.Citation1,Citation52 However, if chronic blood loss is confirmed by fecal occult blood and ECT, surgery should be performed immediately.

Increasing number of small stromal tumors are being treated with endoscopic techniques. Endoscopy presents a number of advantages: short-term efficacy is acceptable, but the risk of long-term recurrence remains uncertain. However, endoscopic treatment has some limitations, related to the size and location of the tumor. In addition, the R0 resection rate is not as good as that of traditional surgery and carries a risk of GI tract perforation. Therefore, endoscopic treatment can increase the risk of tumor bleeding and rupture.Citation23 Therefore, larger tumors should be treated with surgery to ensure maintenance of tumor integrity.

At present, laparoscopic techniques are developing rapidly, but the indications for surgical treatment of stromal tumors remain controversial. Some studies have shown that laparoscopic surgery can reduce recent complications and have no effect on the long-term prognosis of the tumor.Citation53,Citation54 For stomach tumors with a diameter <5 cm, laparoscopic wedge resection is recommended.Citation2 Endoscopic retrieval bag is used to collect and remove the specimen, and forceps are contraindicated because of the risk of tumor rupture.

Traditional surgical methods continue to account for most treatments for stromal tumors, owing to the ease of the operation, and the higher R0 resection rate. Primary GISTs tend to transfer to, rather than invade adjacent structures. Therefore, the conventional wedge resection or local resection can be performed without routine lymph node dissection.Citation55 The purpose of the surgery is to achieve negative margins (R0 resection). R1 resection or positive margins are not recommended for reoperation. Nevertheless, there is no evidence that the prognosis for R1 resections is worse than R0 resections.Citation56,Citation57 McCarter et al divided tumors into 3 groups: R0 (grossly and histologically negative margin), R1 (grossly negative but histologically positive margins), and R2 (grossly positive margins). The risks of recurrence were assessed without imatinib. No significant differences in outcome were found.Citation58 Pathological specimens should be immediately evaluated for capsule rupture. It is recommended to collect fresh or frozen tissues, as new molecular pathology assessments and gene analysis can be performed soon after surgery.Citation4

For patients with large tumors and chronic bleeding, oral imatinib is recommended. The reduction of tumor volume is expected to achieve optimal surgical outcome and reduce postoperative recurrence. If acute hemorrhage is not controlled, emergency surgical treatment becomes necessary. Approximately 15%–47% of patients have distant metastases at diagnosis, with common sites being the liver, peritoneum, and omentum.Citation31,Citation59,Citation60 If this is the case, targeted therapy should be performed first. NCCN recommends imatinib prior to surgery as neoadjuvant treatment, including for patients with incomplete resection or high risk of recurrence after resection.Citation13 It is not recommended that patients with D842V PDGFRA mutations use imatinib because of well-known resistance of these tumors to drugs and TKIs.

The surgery should involve as little disruption of healthy tissue as possible so as to reduce other surgical complications and to improve postoperative quality of life. The target drugs should be discontinued 5–7 days prior to surgery and restarted 2 weeks after surgery. Multidisciplinary team (MDT) methods include endoscopy and pathology. It is necessary for the consultants from departments of radiology, oncology, and surgery to develop individualized treatment regimens.

Small GISTs without gastrointestinal bleeding do not require any particular treatment; however, conventional follow-up remains important. If bleeding occurs, immediate treatment becomes necessary. Many studies indicate that small stromal tumors can be managed expectantly, but when bleeding occurs, there is a high probability of tumor necrosis and ulceration, suggesting that the tumor is developing rapidly, leading to poor prognosis.Citation16,Citation17

Postoperative management of GIST

Genetic testing should be performed routinely to guide the medication regimen. The most recent European consensus proposed that the KIT and PDGFRA gene mutation can be used to analyze and confirm the diagnosis of GISTs, especially in cases with negative CD117.Citation61 CT is the most effective modality for follow-up. Here, we recommend enhanced abdominal and pelvic CT. In low-risk groups, CT can be performed yearly during the first 5 years. For the middle-and high-risk groups, it is recommended every 6 months. If medication is discontinued, it is recommended that CT examination be performed every 3–4 months during the first 2 years and every 6–12 months in the following 10 years.Citation62 We suggest that patients with interstitial tumors with hemorrhage be managed similar to the high-risk group.

According to NCCN guidelines, patients in the moderate- and high-risk groups should be treated with imatinib for 1–3 years to reduce the possibility of recurrence. The benefits and tolerability of imatinib for 5 years are currently under study. However, there is not enough scientific evidence to support the imatinib adjuvant therapy in patients with moderate risk.Citation4 In , many studies on imatinib and other targeted drugs have gradually changed the postoperative management of GISTs. The usual dose of imatinib is 400 mg/day. The average duration of resistance to imatinib followed by progression is 2–2.5 years. For patients who use imatinib 400 mg/day, if progression occurs, the dose can be increased to 800 mg/day.Citation63–Citation65 The higher dose may improve the patients’ progression-free survival and overall survival.Citation66 KIT exon 9 mutation requires oral administration of 600–800 mg/day, although the dosage has never been prospectively confirmed.Citation23 The study by Blanke et alCitation67 suggested that higher doses of imatinib do not improve the survival time due to side effects. However, in GIST patients with exon 9 mutations, the relative risk decreased by 61%.Citation68 If the higher dose of imatinib is not tolerated, or the disease progresses, sunitinib can provide significant, persistent clinical benefits in patients with imatinib resistance or intolerance.Citation69 Those who use imatinib preoperatively for neoadjuvant therapy should have a total course of 3 years.Citation55 But 26% of the patients stopped using imatinib for a variety of reasons.Citation65 A number of studies have shown that, compared with patients who continued treatment, patients who took imatinib for only 1 year had significantly higher progression rates 3 years later.Citation70,Citation71

Table 2 Important clinical trials in GISTs in recent years

Mutations detected during treatment are often resistant to TKIs and are known as secondary mutations.Citation35,Citation36 Secondary resistance occurs initially in response to imatinib and progresses to the clonal expansion, making the tumors drug resistant.Citation72 If the increased dose of the disease continues to progress, second-line treatment of sunitinib can be considered. George et alCitation73 showed that sunitinib dose at 37.5 mg/day remained effective, and tolerance was better. Regorafenib, sorafenib, ponatinib, and other multi-targeted TKIs can be selected according to the individual conditions. Multidisciplinary approaches with individualized treatment plans are essential.

Prognostic factors

Risk factors for GIST recurrence include location, size, numbers of mitotic figures, and tumor rupture.Citation1,Citation74 Among these, number of mitotic figures is the most important. Whether KIT, PDGFRA mutations, and gastrointestinal bleeding should be added to the risk stratification scheme remains controversial.

In other malignant tumors of the digestive system, hematogenous spread is an important mode of metastasis. Prognosis becomes poor once hematogenous metastasis occurs. Tumor spread occurs easily following rupture and bleeding. Malignant tumor bleeding is often accompanied by infection or perforation, complicating clinical treatment. The opportunity to perform surgery is often lost when the disease is discovered in late stage or when the patient cannot tolerate surgery. Most tumor bleeding during the perioperative period requires transfusion. One study suggests that perioperative blood transfusion may be related to low immune function, thereby increasing the possibility of tumor recurrence.Citation75

Intraoperative blood loss also impacts prognosis. The less blood loss at surgery, the better the prognosis. This may be due to the fact that bleeding is often related to vascular invasion or serosal involvement.Citation76 Blood from tumors may induce mesothelial cells to release large amounts of cellulose into the peritoneum, giving rise to favorable conditions for tumor implantation and growth.Citation77,Citation78 The 5-year survival rate of gastrointestinal tumors with bleeding and perforation is only 24%, possibly due to peritoneal dissemination.Citation79 However, this mechanism needs further study and confirmation.

Stromal tumor bleeding may be caused by the enhancement of tumor invasion to mucous membrane after gene mutation, leading to hemorrhage caused by destruction of the mucosal layer. Recently, a number of studies have highlighted the ability of GISTs to produce angiogenic factors that not only enhance feeding of tumors but also mediate tumor infiltration. The endothelial cell markers CD31, CD34, and FVIII-Ragd are commonly used to mark neovascularization and tumor growth.Citation80 Although expression of CDll7 and CD34 in GIST plays an important role in the diagnosis, the relationship of these markers with bleeding and prognosis is not clear.Citation81

Conclusion

In the latest version of the NCCN guidelines, tumor size, location, number of mitotic figures, and tumor rupture are noted as risk factors for grading purposes. Although the mechanism of bleeding in GISTs is not yet fully understood, existing studies suggest that GISTs associated with bleeding tends to indicate poor prognosis. The risk stratification of GIST recurrence is closely related to prognosis, which determines subsequent treatment. We believe that recurrence risk classification of GISTs will improve through future studies. With the increasing popularity of imaging and EUS, the diagnostic success rate of GISTs is increasing. There is a rapid increase in basic research on GISTs. The pathological and biological characteristics are becoming clearer. With the continued appearance of tyrosinase inhibitors, such as imatinib, the prognosis of GISTs has improved significantly. Some late-stage cases that cannot be treated by surgery, as well as patients who cannot use the standard medications, may benefit from MDT and translational medicine. GIST requires multidisciplinary management, which improves both prognosis and quality of life.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Scientific Research of Special-Term Professor from the Educational Department of Liaoning Province, China (Liao Cai Zhi Jiao No. 2012-512).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MiettinenMLasotaJGastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sitesSemin Diagn Pathol200623708317193820

- LankeGLeeJHHow best to manage gastrointestinal stromal tumorWorld J Clin Oncol2017813514428439494

- MiettinenMMajidiMLasotaJPathology and diagnostic criteria of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): a reviewEur J Cancer200238Suppl 5S39S51

- PovedaAGarcía Del MuroXLópez-GuerreroJAGEIS guidelines for gastrointestinal sarcomas (GIST)Cancer Treat Rev20175510711928351781

- CarneyJAGastric stromal sarcoma, pulmonary chondroma, and extra-adrenal paraganglioma (Carney Triad): natural history, adrenocortical component, and possible familial occurrenceMayo Clin Proc19997454355210377927

- TakazawaYSakuraiSSakumaYGastrointestinal stromal tumors of neurofibromatosis type I (von Recklinghausen’s disease)Am J Surg Pathol20052975576315897742

- JiangZXZhangSJPengWJYuBHRectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: imaging features with clinical and pathological correlationWorld J Gastroenterol2013193108311623716991

- RammohanASathyanesanJRajendranKA gist of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a reviewWorld J Gastrointest Oncol2013510211223847717

- NilssonBBümmingPMeis-KindblomJMGastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era–a population-based study in western SwedenCancer200510382182915648083

- KramerKKnippschildUMayerBImpact of age and gender on tumor related prognosis in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST)BMC Cancer2015155725886494

- ConlonKCCasperESBrennanMFPrimary gastrointestinal sarcomas: analysis of prognostic variablesAnn Surg Oncol1995226317834450

- StilesZERistTMDicksonPVImpact of body mass index on the short-term outcomes of resected gastrointestinal stromal tumorsJ Surg Res201721712313028595816

- von MehrenMRandallRLBenjaminRSSoft tissue sarcoma, version 22016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncologyJ Natl Compr Canc Netw201614675878627283169

- DemetriGDvon MehrenMAntonescuCRNCCN Task Force report: update on the management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumorsJ Natl Compr Canc Netw20108Suppl 2S1S41 quiz S42–S44

- LvALiZTianXSKP2 high expression, KIT exon 11 deletions, and gastrointestinal bleeding as predictors of poor prognosis in primary gastrointestinal stromal tumorsPLoS One20138e6295123690967

- LiuQLiYDongMKongFDongQGastrointestinal bleeding is an independent risk factor for poor prognosis in GIST patientsBiomed Res Int20172017715240628589146

- YinZGaoJLiuWClinicopathological and prognostic analysis of primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding: a 10-year retrospective studyJ Gastrointest Surg20172179280028275959

- ESMO / European Sarcoma Network Working GroupGastrointestinal stromal tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-upAnn Oncol201223Suppl 7vii49vii5522997454

- GoldJSDematteoRPCombined surgical and molecular therapy: the gastrointestinal stromal tumor modelAnn Surg200624417618416858179

- SircarKHewlettBRHuizingaJDChorneykoKBerezinIRiddellRHInterstitial cells of Cajal as precursors of gastrointestinal stromal tumorsAm J Surg Pathol19992337738910199467

- CorlessCLSchroederAGriffithDPDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: frequency, spectrum and in vitro sensitivity to imatinibJ Clin Oncol2005235357536415928335

- PantaleoMAAstolfiAIndioVSDHA loss-of-function mutations in KIT-PDGFRA wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumors identified by massively parallel sequencingJ Natl Cancer Inst201110398398721505157

- LimKTTanKYCurrent research and treatment for gastrointestinal stromal tumorsWorld J Gastroenterol2017234856486628785140

- SøreideKSandvikOMSøreideJAGiljacaVJureckovaABulusuVRGlobal epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST): a systematic review of population-based cohort studiesCancer Epi-demiol2016403946

- HeinrichMCOwzarKCorlessCLCorrelation of kinase genotype and clinical outcome in the North American Intergroup Phase III Trial of imatinib mesylate for treatment of advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor: CALGB 150105 Study by Cancer and Leukemia Group B and Southwest Oncology GroupJ Clin Oncol2008265360536718955451

- CorlessCLFletcherJAHeinrichMCBiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumorsJ Clin Oncol2004223813382515365079

- Sarlomo-RikalaMKovatichAJBaruseviciusAMiettinenMCD117: a sensitive marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors that is more specific than CD34Mod Pathol1998117287349720500

- HirotaSIsozakiKMoriyamaYGain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumorsScience19982795775809438854

- DeMatteoRPBallmanKVAntonescuCRLong-term results of adjuvant imatinib mesylate in localized, high-risk, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor: ACOSOG Z9000 (Alliance) intergroup phase 2 trialAnn Surg201325842242923860199

- MiettinenMLasotaJGastrointestinal stromal tumors–definition, clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features and differential diagnosisVirchows Arch200143811211213830

- HoMYBlankeCDGastrointestinal stromal tumors: disease and treatment updateGastroenterology20111401372.e21376.e221420965

- LasotaJMiettinenMClinical significance of oncogenic KIT and PDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumoursHistopathol-ogy200853245266

- HeinrichMCCorlessCLDuensingAPDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumorsScience200329970871012522257

- IsozakiKHirotaSGain-of-function mutations of receptor tyrosine kinases in gastrointestinal stromal tumorsCurr Genomics2006746947518369405

- ReichardtPHogendoornPCTamboriniEGastrointestinal stromal tumors I: pathology, pathobiology, primary therapy, and surgical issuesSemin Oncol20093629030119664490

- Martín-BrotoJRubioLAlemanyRLópez-GuerreroJAClinical implications of KIT and PDGFRA genotyping in GISTClin Transl Oncol20101267067620947481

- Ben-AmiEBarysauskasCMvon MehrenMLong-term follow-up results of the multicenter phase II trial of regorafenib in patients with metastatic and/or unresectable GI stromal tumor after failure of standard tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapyAnn Oncol2016271794179927371698

- ParkSHRyuMHRyooBYSorafenib in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors who failed two or more prior tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a phase II study of Korean gastrointestinal stromal tumors study groupInvest New Drugs2012302377238322270258

- DemetriGDCasaliPGBlayJYA phase I study of single-agent nilotinib or in combination with imatinib in patients with imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumorsClin Cancer Res2009155910591619723647

- CorlessCLBallmanKVAntonescuCRPathologic and molecular features correlate with long-term outcome after adjuvant therapy of resected primary GI stromal tumor: the ACOSOG Z9001 trialJ Clin Oncol2014321563157024638003

- SleijferSSeynaeveCWiemerEVerweijJPractical aspects of managing gastrointestinal stromal tumorsClin Colorectal Cancer20066Suppl 1S18S2317101064

- SorourMAKassemMIGhazalAel-HEl-RiwiniMTAbu NasrAGastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) related emergenciesInt J Surg20141226928024530605

- AjdukMMikulićDSebecićBSpontaneously ruptured gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of the jejunum mimicking acute appendicitisColl Antropol20042893794115666631

- CaterinoSLorenzonLPetruccianiNGastrointestinal stromal tumors: correlation between symptoms at presentation, tumor location and prognostic factors in 47 consecutive patientsWorld J Surg Oncol201191321284869

- BaMCQingSHHuangXCWenYLiGXYuJDiagnosis and treatment of small intestinal bleeding: retrospective analysis of 76 casesWorld J Gastroenterol2006127371737417143959

- BlanchardDKBuddeJMHatchGFTumors of the small intestineWorld J Surg20002442142910706914

- HwangJHSaundersMDRulyakSJShawSNietschHKimmeyMBA prospective study comparing endoscopy and EUS in the evaluation of GI subepithelial massesGastrointest Endosc20056220220816046979

- NaHKLeeJHParkYSYields and utility of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided 19-gauge trucut biopsy versus 22-gauge fine needle aspiration for diagnosing gastric subepithelial tumorsClin Endosc20154815215725844344

- KobayashiKGuptaSTrentJCHepatic artery chemoembolization for 110 gastrointestinal stromal tumors: response, survival, and prognostic factorsCancer20061072833284117096432

- Van den AbbeeleADThe lessons of GIST–PET and PET/CT: a new paradigm for imagingOncologist200813Suppl 281318434632

- GayedIVuTIyerRThe role of 18F-FDG PET in staging and early prediction of response to therapy of recurrent gastrointestinal stromal tumorsJ Nucl Med2004451172114734662

- TanYTanLLuJEndoscopic resection of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumorsTransl Gastroenterol Hepatol2017211529354772

- PiessenGLefèvreJHCabauMLaparoscopic versus open surgery for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: what is the impact on postoperative outcome and oncologic results?Ann Surg2015262831839 discussion 829–84026583673

- NovitskyYWKercherKWSingRFLong-term outcomes of laparoscopic resection of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumorsAnn Surg2006243738745 discussion 745–74716772777

- KeungEZRautCPManagement of gastrointestinal stromal tumorsSurg Clin North Am20179743745228325196

- NishidaTBlayJYHirotaSKitagawaYKangYKThe standard diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on guidelinesGastric Cancer20161931426276366

- ZhiXJiangBYuJPrognostic role of microscopically positive margins for primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysisSci Rep201662154126891953

- McCarterMDAntonescuCRBallmanKVMicroscopically positive margins for primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors: analysis of risk factors and tumor recurrenceJ Am Coll Surg20122155359 discussion 59–6022726733

- QuekRGeorgeSGastrointestinal stromal tumor: a clinical overviewHematol Oncol Clin North Am200923697819248971

- DeMatteoRPLewisJJLeungDMudanSSWoodruffJMBrennanMFTwo hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survivalAnn Surg2000231515810636102

- ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working GroupGastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-upAnn Oncol201425Suppl 3iii21iii2625210085

- JoensuuHMartin-BrotoJNishidaTReichardtPSchöffskiPMakiRGFollow-up strategies for patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumour treated with or without adjuvant imatinib after surgeryEur J Cancer2015511611161726022432

- KeungEZFairweatherMRautCPThe role of surgery in metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumorsCurr Treat Options Oncol201617826820287

- VadakaraJvon MehrenMGastrointestinal stromal tumors: management of metastatic disease and emerging therapiesHematol Oncol Clin North Am20132790592024093167

- von MehrenMGastrointestinal stromal tumorsJ Clin Oncol20183613614329220298

- CasaliPGZalcbergJLe CesneATen-year progression-free and overall survival in patients with unresectable or metastatic GI stromal tumors: long-term analysis of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Italian Sarcoma Group, and Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group Intergroup Phase III randomized trial on imatinib at two dose levelsJ Clin Oncol2017351713172028362562

- BlankeCDRankinCDemetriGDPhase III randomized, inter-group trial assessing imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033J Clin Oncol20082662663218235122

- Debiec-RychterMSciotRLe CesneAKIT mutations and dose selection for imatinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumoursEur J Cancer20064281093110316624552

- DemetriGDvan OosteromATGarrettCREfficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trialLancet20063681329133817046465

- BlayJYLe CesneARay-CoquardIProspective multicentric randomized phase III study of imatinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors comparing interruption versus continuation of treatment beyond 1 year: the French Sarcoma GroupJ Clin Oncol2007251107111317369574

- Le CesneARay-CoquardIBuiBNDiscontinuation of imatinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after 3 years of treatment: an open-label multicentre randomised phase 3 trialLancet Oncol20101194294920864406

- HallerFDetkenSSchultenHJSurgical management after neo-adjuvant imatinib therapy in gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) with respect to imatinib resistance caused by secondary KIT mutationsAnn Surg Oncol20071452653217139461

- GeorgeSBlayJYCasaliPGClinical evaluation of continuous daily dosing of sunitinib malate in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after imatinib failureEur J Cancer2009451959196819282169

- RubinBPBlankeCDDemetriGDProtocol for the examination of specimens from patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumorArch Pathol Lab Med201013416517020121601

- JagoditschMPozgainerPKlinglerATschmelitschJImpact of blood transfusions on recurrence and survival after rectal cancer surgeryDis Colon Rectum2006491116113016779711

- DharDKKubotaHTachibanaMLong-term survival of trans-mural advanced gastric carcinoma following curative resection: multivariate analysis of prognostic factorsWorld J Surg200024588593 discussion 593–59410787082

- FernandezPMPatiernoSRRicklesFRTissue factor and fibrin in tumor angiogenesisSemin Thromb Hemost2004303144

- AoyagiKKouhujiKYanoSVEGF significance in peritoneal recurrence from gastric cancerGastric Cancer2005815516316086118

- SteigenSEBjerkehagenBHauglandHKDiagnostic and prognostic markers for gastrointestinal stromal tumors in NorwayMod Pathol200821465317917670

- MinhajatRMoriDYamasakiFSugitaYSatohTTokunagaOOrgan-specific endoglin (CD105) expression in the angiogenesis of human cancersPathol Int20065671772317096728

- ParkSSRyuJSOhSYKimWBLeeJHChaeYSSurgical outcomes and immunohistochemical features for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTS) of the stomach: with special reference to prognostic factorsHepatogastroenterology2007541454145717708275

- MajerIMGelderblomHvan den HoutWBCost-effectiveness of 3-year vs 1-year adjuvant therapy with imatinib in patients with high risk of gastrointestinal stromal tumour recurrence in the Netherlands; a modelling study alongside the SSGXVIII/AIO trialJ Med Econ2013161106111923808902

- PatrikidouAKey messages from the BFR14 trial of the French Sarcoma GroupFuture Oncol20171327328427624671

- KangYKRyuMHYooCResumption of imatinib to control metastatic or unresectable gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (RIGHT): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trialLancet Oncol2013141175118224140183

- CasaliPGLe CesneAPoveda VelascoATime to definitive failure to the first tyrosine kinase inhibitor in localized GI stromal tumors treated with imatinib as an adjuvant: A European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group Intergroup Randomized Trial in collaboration with the Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group, UNICANCER, French Sarcoma Group, Italian Sarcoma Group, and Spanish Group for Research on SarcomasJ Clin Oncol2015334276428326573069

- MiettinenMSobinLHGastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-upAm J Surg Pathol200529526815613856

- Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumorHum Pathol2008391411141918774375