Abstract

Introduction

To evaluate the prognostic value of circulating Epstein-Barr virus DNA for extra-nodal natural killer/T-Cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKTL), we performed a meta-analysis of published studies that provided survival information with pre-/post-treatment circulating EBV DNA.

Methods

Eligible studies that discussed prognostic significance of circulating EBV DNA in ENKTL were included. Random effects models were applied to obtain the estimated hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals to evaluate prognostic significance (OS and DFS/PFS). Eleven studies covering a total of 562 subjects were included in this analysis.

Results

The summary HRs and 95% CIs of pre-treatment EBV DNA for OS and PFS/DFS were 4.43 (95% CI 2.66–7.39, P<0.00001) and 3.12 (95% CI 1.42–6.85, P=0.005), respectively. The corresponding HRs and 95% CIs of post-treatment EBV DNA for OS and PFS/DFS were 6.28 (95% CI 2.75–14.35, P<0.0001) and 6.57 (95% CI 2.14–20.16, P=0.001). Subgroup analyses indicated a strong trend of prognostic powers with pre-/post-treatment EBV DNA.

Conclusion

With the present evidence, circulating EBV DNA consistently correlated with poorer prognosis in patients with ENKTL which need further investigation in large-scale clinical studies.

Keywords:

Introduction

Extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKTL-NT) is an aggressive malignancy of putative NK-cell origin, with a minority deriving from the T-cell lineage, which presents peculiar clinicopathological features, including angioinvasion, prominent necrosis, and close association with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV).Citation1,Citation2 It occurs most commonly (80%) in the nose and upper aerodigestive tract, and less commonly (20%) in the non-nasal areas (skin, gastrointestinal tract, testis, salivary gland). It generally pursues an aggressive clinical course and has a poor outcome.Citation3 Despite recent application of PET/CT in diagnosis,Citation4 concurrent chemoradiotherapy in early-stage patients,Citation5–Citation7 and newly developed chemotherapy regimen containing L-asparaginase,Citation8,Citation9 it still presents a poor prognosis without an established standard therapy.

Previous studies have identified several prognostic clinicopathological features of ENKTL, including age, primary sites, Ann Arbor stage,Citation10 International prognostic index,Citation11 and Korea-developed NK/T-cell prognostic index.Citation12 However, varying outcomes have been observed in patients with similar prognostic features and undergoing similar therapies, suggesting inherent heterogeneity of tumor and insufficiency of existing prognostication.Citation13 Although several biomarkers have been reported as a prognostic surrogate, prognostic prediction in ENKTL is still dismal. Therefore, it is of great clinical value to identify novel biomarkers, which could be utilized as effective prognostic predictors or possible therapeutic targets, in order to optimize the treatment of patients with ENKTL.

EBV is a human herpes virus that has been confirmed to be in close association with several lymphoid and epithelial malignancies.Citation14,Citation15 It has been reported that inappropriate expression of EBV latent genes combined with environment and genetic cofactors may result in virus-associated malignancies.Citation16 In EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), the putative tumorigenic role has been thoroughly studied and revealed in large-scale studies that circulating EBV DNA is correlated with tumor load and disease prognosis.Citation17–Citation19 Circulating EBV DNA has been detected in plasma or serum in lymphomas, including ENKTL, Hodgkin’s disease, AIDS-related lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Due to the rarity of ENKTL, there is only several small series of studies that reported the prognostic effect of circulating EBV DNA, with various clinical stages, primary locations and treatment regimens.

Hence, we conducted the present meta-analysis to comprehensively explore the potential prognostic impact of circulating EBV DNA in ENKTL.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We searched systematically PubMed, Embase, the Science Citation Index, Cochrane databases, and the Ovid Database for studies discussed prognostic significance of circulating EBV DNA in ENKTL, with no restrictions on language, place of publication, or date of publication (up to June 2017). The main search terms explored were “Epstein-Barr virus”, “EBV”, “EBV load”, “Natural killer/T-cell lymphoma”, “NK/T-cell lymphoma”, and “ENKTL”.

Eligibility criteria

To yield potential relevant publications, we screened the titles and abstracts and author information. Full texts were considered for detailed assessment according to the following inclusion criteria: 1) containing patient cases of ENKTL, 2) measuring the titer of circulating EBV DNA in either plasma or whole blood, and 3) investigating the prognostic significance of EBV DNA titers in ENKTL patients with at least one of the outcome measures of interest. Studies excluded from our study were those that: 1) were duplicated publications, and 2) showed no survival data or insufficient data to be extracted.

Data extraction

Two investigators (CW and YZ) independently evaluated each paper and extracted data, and any discrepancy between the 2 researchers was resolved via discussion, with a third investigator if necessary. The following information was extracted: first author, publication year, type of studies, population characteristics (i.e., country, number of patients), clinicopathological characteristics (i.e., anatomical sites, tumor stage), sampling time (pre-treatment, intra-treatment, or post-treatment), detection methods (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR]), EBV DNA positive rate, median EBV DNA copies, end points, and survival data. For 1 study using 2 different primer sets for LMP1 and Bam HI W fragment by RT-PCR, each of the cohorts was considered an independent data set.

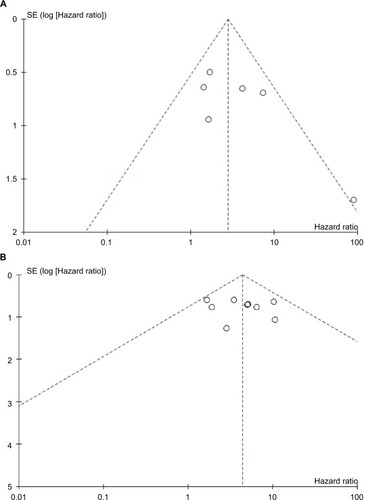

Statistical approaches

Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.2 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre; The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012).Citation22 The estimated hazard ratio (HR) and associated 95% CI were used to evaluate prognostic significance (overall survival [OS] and disease-free survival/progression-free survival [DFS/PFS]). If the HR and its variance were not reported directly in the original study, these values were calculated based on survival data or survival curves using software designed by Tierney.Citation20 The random-effects model was explored to perform the analyses, because this model obtained more conservative results than the fixed-effect model.Citation21 Heterogeneity among the studies was tested using the χ2 test and I2 statistic. A value of I2<25%, within 25%–50%, or >50% was regarded as low, moderate, or significant heterogeneity, respectively. We then evaluated the potential publication bias with funnel plots. The quality of the included studies was assessed with the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) for cohort studies.Citation22

Results

Baseline characteristics

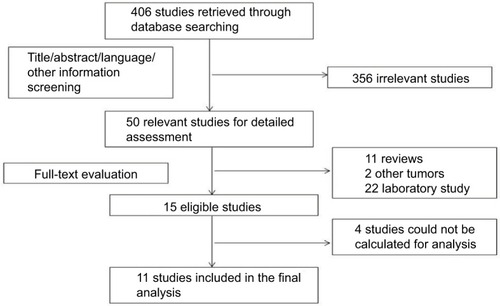

The comprehensive literature search was performed till June 2017, yielding a total of 406 studies. Among these studies, 356 publications were identified as non-English publications, duplicates, or laboratory researches. The remaining 50 studies were thoroughly reviewed, of which 11 studies were appropriate for the meta-analysis ().

Figure 1 Selection of studies.

Note: Flow diagram showing the selection process for the enrolled studies.

Eleven studies (sample size from 15 to 120) with 562 patients, basically located in East Asia, were published between 2002 and 2016.Citation23–Citation33 All the included publications provided data on the correlation between circulating EBV DNA and prognosis in patients with ENKTL. There were 4 studies designed prospectivelyCitation25,Citation27,Citation29,Citation30 and the remaining retrospectively. The most employed detection methods were RT-PCR, with 1 study from JapanCitation24 using 2 different primer sets for LMP1 and Bam HI W fragment, which was considered as 2 independent data sets. For the sample types of included studies, 5 studies used EBV DNA detection in plasma, 1 study used serum, 3 studies from whole blood, 1 study from plasma/MNC, and 1 study from plasma/whole blood. Positive rates of detected EBV DNA irrespective of methods and time points varied from 4.20% to 100% in extracted studies. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in . The quality of the included studies was evaluated with NOS and summarized in .

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the enrolled studies

Table 2 Assessment of study quality using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale

Correlation between EBV DNA and survival outcome

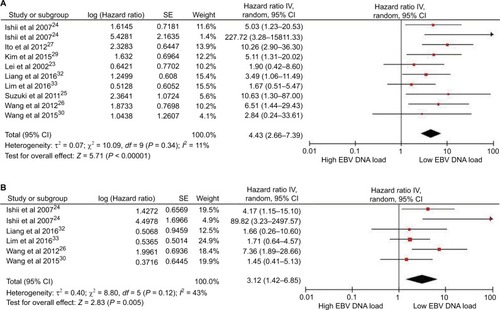

Pre-treatment EBV DNA and OS

A total of 10 cohorts evaluated the relationship between pre-treatment EBV DNA and OS, with 7 cohorts giving the HRs and 95% CIs for OS directly; the HRs in the remaining studies were extracted using the survival curves with P-values. The χ2 test showed low heterogeneity among the studies (P=0.34; I2=11%). The combined pooled HR of the aforementioned studies by a random-effects model was 4.43 (95% CI: 2.66–7.39, P<0.00001), indicating that high EBV DNA load was significantly associated with a poor OS in patients with ENKTL ().

Pre-treatment EBV DNA and DFS/PFS

Five articles reporting the correlation between pre-treatment EBV DNA load and DFS/PFS and 6 cohorts were included for meta-analysis. HR and 95% CI for DFS/PFS were directly extracted from the study reported from 2 cohorts by Ishii et al. The χ2 test showed moderate heterogeneity among the aforementioned studies (P=0.12; I2=43%). The pooled HR with a random-effects model was 3.12 (95% CI: 1.42–6.85, P=0.005), suggesting lower DFS/PFS in ENKTL patients with higher circulating EBV DNA load ().

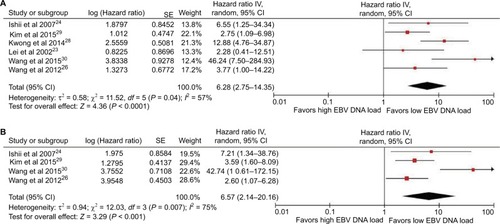

Post-treatment EBV DNA and OS

A total of 6 cohorts evaluated the relationship between post-treatment EBV DNA. The χ2 test showed high heterogeneity among the studies (P=0.04; I2=57%). The combined pooled HR of the aforementioned studies by a random-effects model was 6.28 (95% CI: 2.75–14.35, P<0.0001), indicating that high post-treatment EBV DNA load was significantly associated with a poor OS in patients with ENKTL ().

Figure 3 Estimated hazard ratios for OS and PFS/DFS in post-treatment group.

Notes: (A) Forest plot of OS in post-treatment group. (B) Forest plot of PFS/DFS in post-treatment group.

Abbreviations: DFS, disease-free survival; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Post-treatment EBV DNA and DFS/PFS

Four articles reporting the correlation between post-treatment EBV DNA load and DFS/PFS were included for meta-analysis. The χ2 test showed high heterogeneity among the aforementioned studies (P=0.007; I2=75%). The pooled HR with a random-effects model was 6.57 (95% CI: 2.14–20.16, P=0.001), suggesting a meaningful relationship of a lower DFS/PFS in ENKTL patients with higher post-treatment circulating EBV DNA load ().

Subgroup analysis

To clarify the intra-study inconsistencies, we further evaluated the relationship between pre-/post-treatment EBV DNA and OS in the following subgroup analysis ().

Table 3 Results of subgroup analysis on OS

Type of samples: plasma/serum and whole blood/mononuclear cell (MNC)

Pre-treatment EBV DNA is significantly correlated with OS in both plasma/serum and whole blood/MNC subgroups. The HR and 95% CI for OS in plasma/serum and whole blood/MNC subgroups were 5.30 (95% CI: 3.01–9.33, P<0.00001) and 5.30 (95% CI: 1.68–16.75, P=0.005), respectively. The same relationship was found between post-treatment EBV DNA and OS in subgroup analysis.

Tumor sites: upper aerodigestive tract NK/T-cell lymphoma (UNKTL) and others

When considering primary tumor sites, we further evaluated combined HR and 95% CI for OS in separated subgroups. In UNKTL subgroup, the HR and 95% CI for OS was 7.24 (95% CI: 1.24–42.10, P=0.03). Meanwhile, in the subgroup in which the primary tumor was not limited to UNKTL, the HR and 95% CI for OS was 4.15 (95% CI: 2.40–7.17, P<0.00001). In included studies evaluating the relationship between post-treatment EBV DNA and OS, the HR and 95% CI for OS was 4.68 (95% CI: 1.66–13.19, P=0.003) in ENKTL subgroup, and 7.29 (95% CI: 2.13–24.91, P=0.002) in the subgroup in which the primary tumor was not limited to ENKTL.

Type of study: prospective and retrospective

Prospective and retrospective cohorts were both enrolled in this meta-analysis. In further subgroup analysis, the relationship between EBV DNA and OS remains statistically significant in either prospective or retrospective subgroups. The HR and 95% CI for OS in prospective and retrospective subgroups were 7.53 (95% CI: 3.60–15.78, P<0.00001) and 3.05 (95% CI: 1.52–6.11, P=0.002), respectively. Similar result was found between post-treatment EBV DNA and OS in subgroup analysis.

Sample sizes: N>30 and N<30

In subgroup with large patient number, the HR and 95% CI for OS was 4.81 (95% CI: 2.15–10.79, P=0.0001). Meanwhile, in the subgroup with patient number <30, the HR and 95% CI for OS was 4.43 (95% CI: 1.96–10.06, P=0.0004). When considering the relationship between post-treatment EBV DNA and OS, the HR and 95% CI for OS was 7.75 (95% CI: 2.54–23.61, P=0.0003) in subgroup with large patient number and 3.92 (95% CI: 1.20–12.86, P=0.02) in subgroup with patient number <30.

Discussion

The standard of care for patients with ENKTL remains controversial. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy, chemotherapy regimen containing L-asparaginase, and stem cell transplantationCitation34 have been proposed for patients with ENKTL. However, these high-dose, aggressive therapy strategies do not always translate into survival benefits, with the cumulative probability of 5-year survival ranging from 10% to 55%.Citation35–Citation37 The optimal treatment strategies and prognostic prediction have not been completely defined yet.

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to assess the prognostic value of circulating EBV DNA load in patients with ENKTL. Previous small-scale (N<60) studies have showed that high load of circulating EBV DNA is associated with a poorer survival in ENKTL patients. Hence, a quantitative meta-analysis is urgently required for individualized cancer treatment. Our meta-analysis, which involved a relatively large series of patients, provided robust evidence that circulating EBV DNA load in peripheral blood is significantly associated with poor OS and PFS/DFS in patients with ENKTL.

As a well-known EBV-associated malignancy, the invariable association with episomal infection of EBV in ENKTL cells has strongly implied its tumorigenic role. Fragmented viral DNA has also been found in peripheral blood from EBV-associated malignancies, which was mostly <500 bp in length.Citation38,Citation39 It is reasonable to speculate that measurement of the circulating EBV DNA level may be used as a marker for diagnosis, monitoring treatment response, and prognostication of these EBV-associated malignancies. Previous reports had shown that EBV DNA load has predictive and prognostic significance for EBV-associated malignancies, including NPCCitation40,Citation41 and Hodgkin’s disease.Citation42,Citation43 The diagnostic and prognostic impact has also been evaluated in patients with ENKTL in relatively small-scale studies, suggesting a favorable prognosis with low EBV DNA level. Due to the rarity of the disease, the scales of these cohorts remained relatively small with heterogeneous primary locations, clinical stages, sampling time, and treatment regimens. The present meta-analyses provide stronger evidence that the quantification of EBV DNA level is effective in prognostication in patients with ENKTL.

Besides the potential prognostic impact, other clinical applications of circulating EBV DNA in ENKTL have been evaluated in previous small cohorts of publications, including its diagnostic significance,Citation23,Citation44 relationship with clinicopathological features,Citation26 and predication of therapy response.Citation27,Citation45 Due to the limited data, we did not discuss the aforementioned clinical applications in the present meta-analysis. Large-scale investigation is needed to confirm these potential correlations, which may hypothetically help for patient stratification and personalized therapy.

Circulating EBV DNA can be detected from peripheral plasma, serum, whole blood, or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNCs). There is still controversy regarding selection of the most suitable blood compartment for the detection of EBV DNA. Previous studies suggested that whole blood compartments and PBMNCs demonstrated a higher sensitivity in diagnosis and prognosis than plasma.Citation46,Citation47 However, Spacek et al reported that detection of EBV DNA in plasma was better than in whole blood in predicting prognosis of Hodgkin’s disease.Citation48 In the present studies, peripheral plasma is mostly used as samples to evaluate EBV DNA level, with 2 cohorts from Korea and Japan using whole blood and another study from Japan using PBMNC. Subgroup analysis shows that regardless of sampling type, circulating EBV DNA level constantly remains strongly correlated with patient prognosis. Comparison of sensitivity and accuracy among each blood compartments is needed for further investigation.

Multiple sampling time points were initially considered in our enrolled studies, including pre-, intra-, and post-treatment. Pre-treatment EBV DNA was mostly applied in majority of included studies, due to the relatively reliable prognostic significance regardless of different therapy regimens. On the other hand, multiple assays of EBV DNA in multiple sample times provided more information, which may be used to analyze the dynamic changes of EBV DNA levels during the treatment. Kwong et al investigated circulating EBV DNA, either baseline or post-treatment, in patients with ENKTL treated with SMILE regimen (comprising steroid, methotrexate, ifosfamide, L-asparaginase, and etoposide) and identified 3 DNA dynamic change patterns. It showed that negative EBV DNA after SMILE with pattern A change in EBV DNA (persistently undetectable) significantly correlated with lower tumor load and superior outcome.Citation28 The prognostic impact of EBV DNA in ENKTL is reliable and the considerations for circulating EBV DNA levels before and after treatment remains controversial, which deserves to be investigated in future studies.

It should be pointed out that limitations exist in the meta-analysis that allow us to interpret the results with caution. First, this meta-analysis was based on published data from the enrolled heterogeneous studies, and individual patient data was not available for further investigation. Second, the total number of patients from included studies was relatively small comparing with meta-analysis for other types of cancers. With regard to pediatric patients, 2 cohorts out of 11 studies included patients who were <14 years of age with no detailed information on the exact patient number, which might include rare pediatric cases. Therefore, the current meta-analysis included rare pediatric cases that were not enough for further analysis. Considering the rarity of ENKTL worldwide, it is difficult to conduct large prospective studies. High-quality meta-analysis may provide more reliable evidence to guide treatment and predict prognosis. Third, the cut-off value of EBV DNA in our enrolled publications varies from 349.9 copies/mL to 6.1×107 copies/mL, implying that there was not a uniform cut-off value to define the high load of circulating EBV DNA in patients with ENKTL, which might lead to heterogeneity.

Conclusion

In summary, our meta-analysis provides convincing evidence supporting the proposition that circulating EBV DNA consistently correlated with prognosis of patients with ENKTL, regardless of primary tumor locations, sampling times, or sample types. However, to confirm this conclusion as well as derived speculations, high-quality, well designed, and large-scale clinical studies of ENKTL are urgently needed.

Novelty and impact statements

In this work, we have for the first time investigated the prognostic value of circulating EBV DNA for ENKTL by meta-analysis based on published data. Our meta-analysis provides convincing evidence supporting the proposition that circulating EBV DNA consistently correlated with prognosis of patients with ENKTL, regardless of primary tumor locations, sampling times, or sample types. To confirm this conclusion, high-quality, well-designed, and large-scale clinical studies of ENKTL are urgently needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 81172209 and No 81602048) and Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (No, S2011020003612).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- TseEKwongYLHow I treat NK/T-cell lymphomasBlood2013121254997500523652805

- ZhangTFuQGaoDGeLSunLZhaiQEBV associated lymphomas in 2008 WHO classificationPathol Res Pract20142102697324355441

- ChanJKCQuintanilla-MartinezLFerryJAPehSCExtranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal typeSwerdlowSHCampoEHarrisNLWHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid TissuesLyon, FranceIARC2008285288

- ZhouXLuKGengLLiXJiangYWangXUtility of PET/CT in the diagnosis and staging of extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysisMedicine (Baltimore)20149328e25825526450

- JiangLLiSJJiangYMThe significance of combining radiotherapy with chemotherapy for early stage extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: a systematic review and meta-analysisLeuk Lymphoma20145551038104823885795

- KimSJKimKKimBSPhase II trial of concurrent radiation and weekly cisplatin followed by VIPD chemotherapy in newly diagnosed, stage IE to IIE, nasal, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma: consortium for improving survival of lymphoma studyJ Clin Oncol200927356027603219884539

- YamaguchiMTobinaiKOguchiMPhase I/II study of concurrent chemoradiotherapy for localized nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG0211J Clin Oncol200927335594560019805668

- LinNSongYZhengWA prospective phase II study of L-asparaginase-CHOP plus radiation in newly diagnosed extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal typeJ Hematol Oncol201364423816178

- JiangMZhangHJiangYPhase 2 trial of “sandwich” L-asparaginase, vincristine, and prednisone chemotherapy with radiotherapy in newly diagnosed, stage IE to IIE, nasal type, extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphomaCancer2012118133294330122139825

- CheungMMChanJKLauWHNganRKFooWWEarly stage nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma: clinical outcome, prognostic factors, and the effect of treatment modalityInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys200254118219012182990

- LiYXFangHLiuQFClinical features and treatment outcome of nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma of Waldeyer ringBlood200811283057306418676879

- LeeJSuhCParkYHExtranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma, nasal-type: a prognostic model from a retrospective multicenter studyJ Clin Oncol200624461261816380410

- KimTMLeeSYJeonYKLymphoma Subcommittee of the Korean Cancer Study GroupClinical heterogeneity of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: a national survey of the Korean Cancer Study GroupAnn Oncol20081981477148418385201

- LeiKIChanLYChanWYJohnsonPJLoYMQuantitative analysis of circulating cell-free Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA levels in patients with EBV-associated lymphoid malignanciesBr J Haematol2000111123924611091207

- LeungSFZeeBMaBBPlasma Epstein-Barr viral deoxyribonucleic acid quantitation complements tumor-node-metastasis staging prognostication in nasopharyngeal carcinomaJ Clin Oncol200624345414541817135642

- WilliamsHCrawfordDHEpstein-Barr virus: the impact of scientific advances on clinical practiceBlood2006107386286916234359

- ChaiSJPuaKCSalehAMalaysian NPC Study GroupClinical significance of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA loads in a large cohort of Malaysian patients with nasopharyngeal carcinomaJ Clin Virol2012551343922739102

- ZhangYXKangSYChenGABO blood group, Epstein-Barr virus infection and prognosis of patients with non-metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinomaAsian Pac J Cancer Prev201415177459746525227859

- ChenMYinLWuJImpact of plasma Epstein-Barr virus-DNA and tumor volume on prognosis of locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinomaBiomed Res Int2015201561794925802858

- TierneyJFStewartLAGhersiDBurdettSSydesMRPractical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysisTrials200781617555582

- SchmidtFLOhISHayesTLFixed- versus random-effects models in meta-analysis: model properties and an empirical comparison of differences in resultsBr J Math Stat Psychol200962Pt 19712818001516

- WellsGASheaBO’ConnellDThe Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) forassessing the quality if nonrandomized studies inmeta-analyses Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.aspAccessed August 13, 2014

- LeiKIChanLYChanWYJohnsonPJLoYMDiagnostic and prognostic implications of circulating cell-free Epstein-Barr virus DNA in natural killer/T-cell lymphomaClin Cancer Res200281293411801537

- IshiiHOginoTBergerCClinical usefulness of serum EBV DNA levels of BamHI W and LMP1 for Nasal NK/T-cell lymphomaJ Med Virol20077955627217385697

- SuzukiRYamaguchiMIzutsuKNK-cell Tumor Study GroupProspective measurement of Epstein-Barr virus-DNA in plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal typeBlood2011118236018602221984805

- WangZYLiuQFWangHClinical implications of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA in early-stage extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma patients receiving primary radiotherapyBlood2012120102003201022826562

- ItoYKimuraHMaedaYPretreatment EBV-DNA copy number is predictive of response and toxicities to SMILE chemotherapy for extra-nodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal typeClin Cancer Res201218154183419022675173

- KwongYLPangAWLeungAYChimCSTseEQuantification of circulating Epstein-Barr virus DNA in NK/T-cell lymphoma treated with the SMILE protocol: diagnostic and prognostic significanceLeukemia201428486587023842425

- KimSJParkSKangESInduction treatment with SMILE and consolidation with autologous stem cell transplantation for newly diagnosed stage IV extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma patientsAnn Hematol2015941717825082384

- WangLWangHWangJHPost-treatment plasma EBV-DNA positivity predicts early relapse and poor prognosis for patients with extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma in the era of asparaginaseOncotarget2015630303173032626210287

- KimSJChoiJYHyunSHAsia Lymphoma Study GroupRisk stratification on the basis of Deauville score on PET-CT and the presence of Epstein-Barr virus DNA after completion of primary treatment for extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: a multicentre, retrospective analysisLancet Haematol201522e66e7426687611

- LiangRWangZBaiQXNatural killer/T cell lymphoma, nasal type: a retrospective clinical analysis in North-Western ChinaOncol Res Treat2016391–2455226891121

- LimSHHyunSHKimHSPrognostic relevance of pretransplant Deauville score on PET-CT and presence of EBV DNA in patients who underwent autologous stem cell transplantation for ENKTLBone Marrow Transplant201651680781226855154

- EnnishiDMaedaYFujiiNAllogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for advanced extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal typeLeuk Lymphoma20115271255126121599584

- SuzukiRSuzumiyaJYamaguchiMNK-cell Tumor Study GroupPrognostic factors for mature natural killer (NK) cell neoplasms: aggressive NK cell leukemia and extranodal NK cell lymphoma, nasal typeAnn Oncol20102151032104019850638

- YongWZhengWZhangYL-asparaginase-based regimen in the treatment of refractory midline nasal/nasal-type T/NK-cell lymphomaInt J Hematol200378216316712953813

- YouJYChiKHYangMHRadiation therapy versus chemotherapy as initial treatment for localized nasal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma: a single institute survey in TaiwanAnn Oncol200415461862515033670

- LoYMChanWYNgEKCirculating Epstein-Barr virus DNA in the serum of patients with gastric carcinomaClin Cancer Res2001771856185911448896

- ChanKCZhangJChanATMolecular characterization of circulating EBV DNA in the plasma of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and lymphoma patientsCancer Res20036392028203212727814

- LeungSFChanKCMaBBPlasma Epstein-Barr viral DNA load at midpoint of radiotherapy course predicts outcome in advanced-stage nasopharyngeal carcinomaAnn Oncol20142561204120824638904

- LinJCWangWYChenKYQuantification of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal carcinomaN Engl J Med2004350242461247015190138

- MusacchioJGCarvalho MdaGMoraisJCDetection of free circulating Epstein-Barr virus DNA in plasma of patients with Hodgkin’s diseaseSao Paulo Med J2006124315415717119693

- KwonJMParkYHKangJHThe effect of Epstein-Barr virus status on clinical outcome in Hodgkin’s lymphomaAnn Hematol200685746346816534596

- AuWYPangAChoyCChimCSKwongYLQuantification of circulating Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA in the diagnosis and monitoring of natural killer cell and EBV-positive lymphomas in immunocompetent patientsBlood2004104124324915031209

- KimHSKimKHChangMHWhole blood Epstein-Barr virus DNA load as a diagnostic and prognostic surrogate: extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphomaLeuk Lymphoma200950575776319330658

- StevensSJPronkIMiddeldorpJMToward standardization of Epstein-Barr virus DNA load monitoring: unfractionated whole blood as preferred clinical specimenJ Clin Microbiol20013941211121611283029

- HakimHGibsonCPanJComparison of various blood compartments and reporting units for the detection and quantification of Epstein-Barr virus in peripheral bloodJ Clin Microbiol20074572151215517494720

- SpacekMHubacekPMarkovaJPlasma EBV-DNA monitoring in Epstein-Barr virus-positive Hodgkin lymphoma patientsAPMIS20111191101621143522