Abstract

Background and purpose

Numerous studies have demonstrated that sarcomatoid differentiation is linked to the risk of renal cell carcinoma (RCC). However, its actual clinicopathological impact remains inconclusive. Therefore, we undertook a meta-analysis to evaluate the pathologic and prognostic impacts of sarcomatoid differentiation in patients with RCC by assessing cancer-specific survival, overall survival, recurrence-free survival, progression-free survival, and cancer-specific mortality.

Materials and methods

In accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis statement, relevant studies were collected systematically from PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science to identify relevant studies published prior to January 2018. The pooled effects (hazard ratios, odds ratios, and standard mean differences) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to investigate the association of sarcomatoid differentiation with cancer prognosis and clinicopathological features.

Results

Thirty-five studies (N=11,261 patients [n=59–1,437 per study]) on RCC were included in this meta-analysis. Overall, the pooled analysis suggested that sarcomatoid differentiation was significantly associated with unfavorable cancer-specific survival (HR=1.46, 95% CI: 1.26–1.70, p<0.001), overall survival (HR=1.59, 95% CI: 1.42–1.78, p<0.001), progression-free survival (HR=1.61, 95% CI: 1.35–1.91, p<0.001), recurrence-free survival (HR=1.60, 95% CI: 1.29–1.99, p<0.001), and cancer-specific mortality (HR=2.36, 95% CI: 1.64–3.41, p<0.001) in patients with RCC. Moreover, sarcomatoid differentiation was closely correlated with TNM stage (III/IV vs I/II: OR=1.84, 95% CI: 1.12–3.03, p=0.017), Fuhrman grade (III/IV vs I/II: OR=8.37, 95% CI: 2.92–24.00, p<0.001), lymph node involvement (N1 vs N0: OR=1.88, 95% CI: 1.08–3.28, p=0.026), and pathological types (clear cell RCC-only vs mixed type: OR=0.48, 95% CI: 0.29–0.80, p=0.005), but was not related to gender (male vs female, OR=0.86, 95% CI: 0.58–1.28, p=0.464) and average age (SMD=−0.02, 95% CI: −0.20–0.17, p=0.868).

Conclusion

This study suggests that sarcomatoid differentiation in histopathology is associated with poor clinical outcome and advanced clinicopathological features in RCC and could serve as a poor prognostic factor for RCC patients.

Introduction

As the 8th most common cancer worldwide, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for 2–3% of all adult malignanciesCitation1 and causes approximately 140,000 deaths per year.Citation2 Although most patients with RCC can be cured by surgical resection, more than 25% of patients still experience local recurrence or distant metastasis.Citation3 Given that clear cell RCC (ccRCC) accounts for approximately 80% of all RCCs,Citation4 it should be noted that a particular histologic subtype is accompanied by different manifestations and pharmacologic consequences.Citation5 Therefore, ideally, the clinical significance of a particular prognostic factor should always be independently validated for each histologic subtype.

RCC with sarcomatoid differentiation is a rare variant of RCC that accounts for 1–8% of all RCC histologic subtypes.Citation6 Histologically, sarcomatoid is a term used to describe morphologic changes within an RCC. Previous research demonstrates that sarcomatoid differentiation is associated with a more aggressive disease and poor outcome after surgical resection or immunotherapy.Citation7,Citation8 The International Society of Urological Pathology recommended that the presence of sarcomatoid differentiation should be classified as Grade 4 regardless of the histological subtype or nuclear grade.Citation9 Given small sample sizes and different conditions, minimal evidence is available on the prognostic role of sarcomatoid differentiation for RCC.

To further clarify the prognostic and clinicopathological value of sarcomatoid differentiation in RCC, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate whether the presence of sarcomatoid differentiation has a prognostic impact on cancer-specific survival (CSS), overall survival (OS), recurrence-free survival (RFS), progression-free survival (PFS), and cancer-specific mortality (CSM).

Materials and methods

Literature search

In accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis guideline,Citation10 we systematically searched for relevant studies in PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science until January 2018. The following terms were included in the search strategy: “sarcomatoid differentiation,” “renal cell cancer OR renal cell carcinoma”, and “prognostic factor OR oncologic outcome.” These terminologies were used in all possible combinations, and the language of publications was restricted to English. Moreover, the reference lists of the included articles were scanned manually for additional potentially relevant studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies eligible for inclusion in our meta-analysis had to meet the following criteria: 1) studies that included RCC and where the expression of sarcomatoid differentiation was pathologically confirmed; 2) studies in which the association between sarcomatoid differentiation and the prognosis of RCC (CSS, OS, RFS, PFS, and CSM) were reported; and 3) studies wherein HRs and their 95% CIs for survival analysis were reported or could be computed from given data. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) reviews, case reports, conference records, and comments and non-original articles; 2) studies that did not analyze the sarcomatoid differentiation, clinicopathological features, and survival outcome; 3) studies with insufficient data to estimate the HRs and 95% CIs; and 4) studies that were not published in English. In addition, when multiple reports describing the same population were published, the most recent or most complete report was used.

Data extraction and quality assessments

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 2 investigators independently extracted the following data from eligible studies: first author’s name, year of publication, country, period of recruitment, study design, age of patients, gender ratio, number of patients, follow-up time, histology, nuclear grade, pathology tumor (pT) stage, and survival end point. If multivariate and univariate analyses were both conducted in the same study, only the results of multivariate analysis were extracted because this information is more accurate as it accounts for confounding factors. When disagreement occurred, the issue was resolved through discussion among the authors. The quality in prognosis studiesCitation11 tool was used to assess the methodological quality of each included study. Each study can be assessed by 6 important bias domains: study participation, study attrition, prognostic factor measurement, study confounding, outcome measurement, and statistical analysis and reporting. Studies from the analysis that are at high risk for any important bias were defined as low quality.

Statistical analysis

The statistical processes in this meta-analysis were undertaken using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Dichotomous variables were calculated by HRs, and pooled HRs with 95% CIs were used to evaluate the association of sarcomatoid differentiation with RCC prognosis (CSS, OS, RFS, PFS, and CSM). Furthermore, we studied the associations between sarcomatoid differentiation and clinical parameters of RCC. Data about Fuhrman grade (III/IV vs I/II), pT stage (pT3–4 vs pT1–2), lymph node involvement (N1 vs N0), pathological types (ccRCC-only vs mixed type), and gender (male vs female) were continuous variables whereas average age was a dichotomous variable. Comparisons of continuous and dichotomous variables were pooled as standard mean differences (SMDs) and ORs.

Statistical heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and Higgins ICitation2 statistic. When ICitation2 <50% or pheterogeneity >0.1, which indicates that no obvious heterogeneity existed among studies, the fixed effects (FE) model was applied; otherwise, the random-effects (RE) model was applied. To obtain a more precise evaluation of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were conducted for CSS, OS, RFS, PFS, and CSM by geographical region, year of publication, pathological types, pT stage, Fuhrman grade, number of patients, and median follow-up. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger’s linear regression test. In addition, sensitivity analyses were used to estimate the robustness of the results by sequential omission of individual studies. A 2-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Literature search

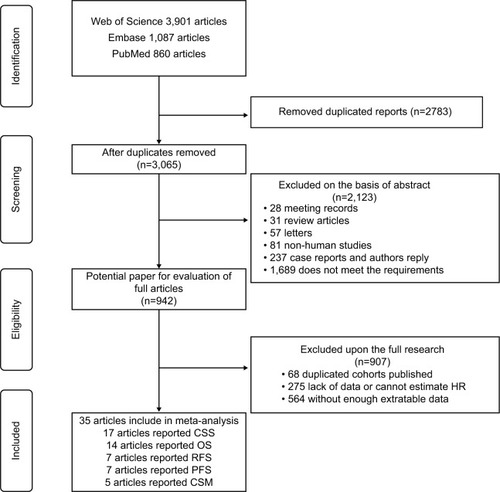

The flowchart depicting the study selection procedure in this meta-analysis is shown in . After the initial search of relevant databases, 5,848 potentially relevant citations were retrieved. In total, 4,906 studies were excluded by reviewing the title and abstract, including 2,783 duplicate reports, 1,770 irrelevant studies, and 353 non-research articles (non-human studies, letters, case reports, meeting records, and reviews). The full-texts of the 942 remaining articles were assessed, and 907 papers were excluded due to insufficient survival information or duplicated cohorts. Finally, in accordance with the inclusion criteria, 35 articles published from 2004 to 2017 about the association of sarcomatoid differentiation and RCC survival were eligible for the meta-analysis.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 35 eligible studiesCitation12–Citation46 are presented in . These studies enrolled 11,261 patients (59–1,437 per study), with a median follow-up ranging from 12.6 to 102 months. Most of the included studies had a retrospective design. Among the included studies, 10 were conducted in America, 7 in China, 6 in Korea, 5 in Europe, 4 at multiple centers, 1 in Mexico, 1 in Egypt, and 1 in Japan. CSS was evaluated in 17 studies, and OS was reported in 14 studies. Both PFS and RFS were reported in 7 studies, and CSM was reported in 5 studies. The characteristics, including tumor features and pathologic outcomes, are summarized in . Sarcomatoid differentiation was detected in (792/11,261) 7.03% of pathological specimens of the included patients. Ten of the included studies were limited to ccRCC, whereas 25 studies involved various tumor types, including ccRCC, papillary RCC, chromophobe RCC, and unclassified variants. The quality in prognosis studies tool was applied to assess the methodological quality of the included studies, demonstrating that all studies were of high quality (Table S1).

Table 1 Main characteristics of the eligible studies

Table 2 Tumor characteristics of the eligible studies

Meta-analysis results

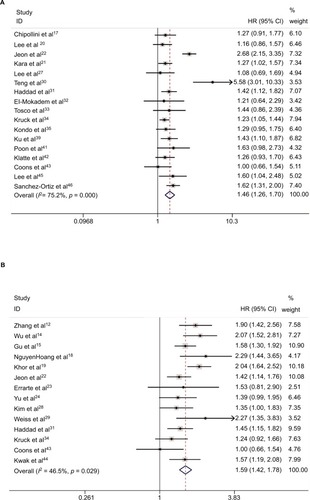

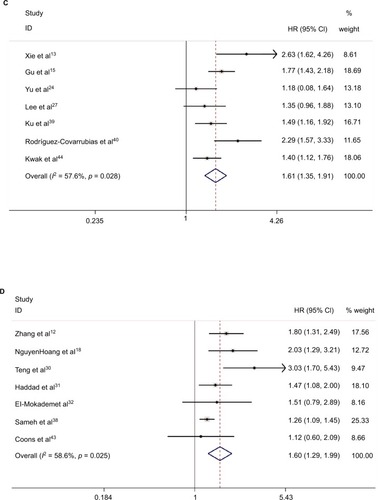

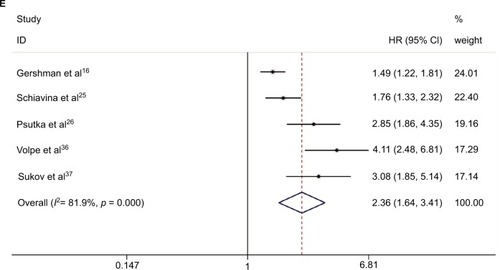

Our meta-analysis demonstrated that sarcomatoid differentiation expression in RCC was associated with poor CSS (RE model, HR=1.46, 95% CI: 1.26–1.70; p<0.001; I2=75.2%; ), OS (RE model, HR=1.59, 95% CI: 1.42–1.78, p<0.001; I2=46.5%; ), PFS (RE model, HR=1.61, 95% CI: 1.35–1.91; p<0.001; I2=57.6%; ), RFS (RE model, HR=1.60, 95% CI: 1.29–1.99, p<0.001; I2= 58.6%; ), and CSM (RE model, HR=2.36, 95% CI: 1.64–3.41; p<0.001; I2=81.9%; ). To explore the heterogeneity between these studies, the significance of sarcomatoid differentiation was evaluated further via subgroup analysis based on the main features, including geographical region, year of publication, pathological types, pT stage, Fuhrman grade, number of patients, and median follow-up (). The results of subgroup analysis suggested sarcomatoid differentiation as a prognostic factor despite heterogeneity among some groups. Of note, heterogeneity decreased significantly in some models, such as geographical region in non-Asian (CSS, OS, and RFS), year of publication before 2013 (CSS, OS, RFS, and CSM), number of patients <250 (CSS, OS, RFS, and CSM), (pT3–4) % ≥50 (CSS, OS, PFS, and CSM), median followup <40 months (CSS, OS, RFS, and CSM), and mixed type pathology (OS and RFS).

Table 3 Summary and subgroup analysis for the eligible studies

Figure 2 Forest plots of studies evaluating the association between sarcomatoid differentiation and clinical outcome of patients with RCC: (A) CSS, (B) OS, (C) PFS, (D) RFS, and (E) CSM.

Note: Weights are from random-effects analysis.

Abbreviations: CSS, cancer-specific survival; OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival; PFS, progression-free survival; CSM, cancer-specific mortality; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

To explore the significance of sarcomatoid differentiation in pathologic diagnosis, we evaluated the relationship between the expression of sarcomatoid differentiation and clinicopathological features. As shown in , sarcomatoid differentiation was significantly related to TNM stage (III/IV vs I/II: OR=1.84, 95% CI: 1.12–3.03, p=0.017, Figure S1A), Fuhrman grade (III/IV vs I/II: OR=8.37, 95% CI: 2.92–24.00, p<0.001, Figure S1B), lymph node involvement (N1 vs N0: OR=1.88, 95% CI: 1.08–3.28, p=0.026, Figure S1C), and pathological type (ccRCC-only vs mixed type: OR=0.48, 95% CI: 0.29–0.80, p=0.005, Figure S1D), However, no significant correlations were observed with regard to gender (male vs female, OR=0.86, 95% CI: 0.58–1.28, p=0.464, Figure S1E) and average age (SMD=−0.02, 95% CI: −0.20–0.17, p=0.868, Figure S1F). No significant heterogeneity was observed in those groups.

Table 4 Meta-analysis of the association between sarcomatoid differentiation and clinicopathological features of RCC

Sensitivity analysis

In sensitivity analysis by sequential omission of individual studies, the pooled HR for CSS ranged from 1.37 (95% CI: 1.22–1.54) to 1.49 (95% CI: 1.28–1.74) (Figure S2A). Similarly, the pooled HR for OS ranged from 1.54 (95% CI: 1.37–1.72) to 1.62 (95% CI: 1.46–1.80) (Figure S2B), for PFS from 1.53 (95% CI:1.31–1.79) to 1.68 (95% CI: 1.41–2.00) (Figure S2C), for RFS from 1.47 (95% CI: 1.23–1.75) to 1.73 (95% CI: 1.39–2.16) (Figure S2D), and for CSM from 2.06 (95% CI: 1.48–2.87) to 2.72 (95% CI: 1.83–4.04) (Figure S2E). These results indicated that the findings were reliable and robust.

Publication bias

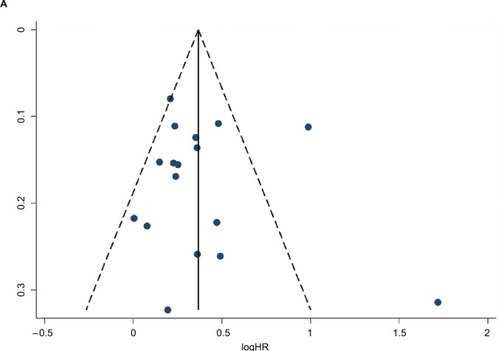

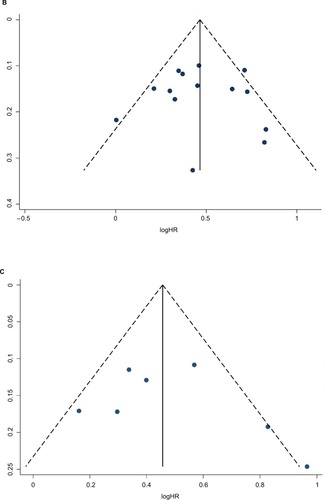

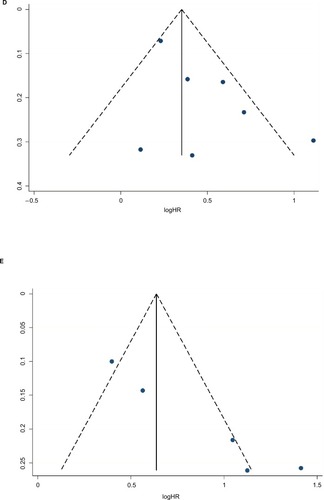

Egger’s tests and funnel plots were conducted to estimate publication bias in the present meta-analysis. As shown in , the funnel plots indicated that the included studies (CSS, OS, RFS, and PFS) had no evident asymmetry. The p-values of the Egger’s tests were all greater than 0.05 in CSS (p-Egger=0.723, ), OS (p-Egger=0.925, ), PFS (p-Egger=0.443, ), and RFS (p-Egger=0.108, ). However, a statistically significant publication bias was founded in CSM (p-Egger=0.003, ).

Discussion

The rate of incidence of RCC has rapidly increased by approximately 2% worldwide during the last decade.Citation47 Although significant advancements have been made in managing renal masses, long-term survival remains unsatisfactory, and the vast majority of patients with RCC still die of their disease. Therefore, RCC patients should be closely followed up, and reliable prognostic biomarkers that evaluate postoperative risks and allow individualized treatment for RCC patients are necessary. In recent years, numerous studies have investigated a wide variety of prognostic factors, such as TNM stage,Citation13 Fuhrman’s grade, and tumor size.Citation48 However, these prognostic variables cannot always make accurate predictions due to the limitation of significant tumor heterogeneity in RCC patients.Citation14 Therefore, novel biomarkers that can distinguish high-risk RCC patients and improve clinical outcomes are desperately needed.

An RCC with sarcomatoid differentiation is a distinct subtype that is defined by the presence of atypical spindle cells and is similar to all forms of sarcoma.Citation49 The reported incidence of sarcomatoid differentiation is between 0.7% and 13.2% of all RCCs,Citation50 which is consistent with our result of 7.03% (792/11,261). Clinically, sarcomatoid differentiation in RCC is associated with more aggressive tumor biology, increased rates of recurrence, and poor survival.Citation28 Furthermore, RCC with sarcomatoid differentiation demonstrates unfavorable responses to targeted therapy.Citation8 According to the 2016 World Health Organization Classification, RCC with sarcomatoid differentiation should not recognized as a separate and distinct entity, indicating that the sarcomatoid component could occur in all types of RCC.Citation51

To date, several studies have examined the prognostic value of sarcomatoid differentiation for RCC patients. However, these results were not consistent. Gu et alCitation15 demonstrated that the presence of sarcomatoid differentiation was significantly associated with poor oncologic outcomes (OS and PFS) for surgically treated RCC patients. Furthermore, Keegan et alCitation5 confirmed that the sarcomatoid component was associated with poor survival even when encountered in low-stage disease. However, a study by Tosco et alCitation33 found that sarcomatoid differentiation failed to independently predict CSM in surgically treated RCC patients. Similarly, Chen et alCitation48 found that the sarcomatoid feature is not a prognostic factor of pT3 RCC for PFS and CSS. Zhang et alCitation49 demonstrate that the presence of rhabdoid differentiation does not confer an increased risk of death from the largest study, to date, of patients with Grade 4 RCC. Although sarcomatoid differentiation is commonly recognized by clinicians as being associated with poor outcomes, no commonly accepted prognostic system for sarcomatoid RCC is currently available due to the low morbidity and lack of study data. With this objective in mind, we first sought to confirm that sarcomatoid differentiation is an independent prognostic feature for RCC patients.

Using the largest sample size to date, this meta-analysis is the most comprehensive study to systematically analyze the prognostic power of sarcomatoid differentiation in patients with RCC. We found that sarcomatoid differentiation was significantly associated with CSS (HR=1.46, p<0.001), OS (HR=1.59, p<0.001), PFS (HR=1.61, p<0.001), RFS (HR=1.60, p<0.001), and CSM (HR=2.36, p<0.001) in RCC patients. In addition, subgroup analyses demonstrated that sarcomatoid differentiation remained a good biomarker regardless of the background of ethnic background, pT stage, nuclear grade, and tumor type. Given the lower sample size of the subgroup (PFS and median follow-up ≥40 months) with a different result (2 studies involving 1,720 patients), we can ignore the inconsistent result to some extent.

Our findings, furthermore, demonstrated that RCC cases exhibiting sarcomatoid differentiation are prone to experiencing a higher nuclear grade (OR=8.37, p<0.001), increased pathological T stage (OR=1.84, p=0.017), lymph node involvement (OR=1.88, p=0.026), and mixed histologic types (OR=0.48, p=0.005). However, sarcomatoid differentiation is not associated with gender (OR=0.86, p=0.464) and average age (SMD= −0.02, p=0.868). Interestingly, although RCCs differ among histological subtypes, we observed no differences on comparing the positive expression of sarcomatoid differentiation between ccRCC and mixed type (CSS, OS, and RFS). In other words, sarcomatoid differentiation may be independently validated as a prognostic factor for each histologic subtype, and this information reflects the risk stratification in the clinical treatment of RCC.

However, several limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. First, significant heterogeneity was detected for several parameters. Although we selected random-effect or fixed-effect models based on heterogeneity, it still existed due to the differences in the included studies. Second, although a comprehensive search strategy was applied to determine eligible studies, it is possible that some eligible studies were not included, which may cause selection bias. Third, the criteria for the presence of sarcomatoid differentiation in pathologic specimens were inconsistent, which may potentially contribute to potential bias. Thus, rigorous morphological criteria should be conducted to standardize the diagnosis of sarcomatoid differentiation. Additionally, a publication bias existed in CSM, thus inflating the estimate for the association of sarcomatoid differentiation with CSM risk.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrated that sarcomatoid differentiation expression was associated with poor pathological features and prognosis. These findings indicate that sarcomatoid differentiation is a potential adverse prognostic marker that could be utilized to divide risk stratification and formulate individualized treatments for patients with RCC. Considering the limitations of the present analysis, larger studies using standardized methods and criteria are required to verify the prognostic roles of sarcomatoid differentiation expression in RCC.

Author contributions

LJZ and BW designed the research. ZLZ and HZ undertook the literature search. HZ and YJF analyzed the data and interpreted the results. LJZ wrote the paper. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CalvoESchmidingerMHengDYGrünwaldVEscudierBImprovement in survival end points of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma through sequential targeted therapyCancer Treat Rev20165010911727664394

- CapitanioUMontorsiFRenal cancerLancet20163871002189490626318520

- MacLennanSImamuraMLapitanMCSystematic review of oncological outcomes following surgical management of localised renal cancerEur Urol201261597299322405593

- LjungbergBBensalahKCanfieldSEAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: 2014 updateEur Urol201567591392425616710

- KeeganKASchuppCWChamieKHellenthalNJEvansCPKoppieTMHistopathology of surgically treated renal cell carcinoma: survival differences by subtype and stageJ Urol2012188239139722698625

- ThomasAZAdibiMSlackRSThe role of metastasectomy in patients with renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid dedifferentiation: a matched controlled analysisJ Urol2016196367868427036304

- JosephRWMillisSZCarballidoEMPD-1 and PD-L1 expression in renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid differentiationCancer Immunol Res20153121303130726307625

- GolshayanARGeorgeSHengDYMetastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapyJ Clin Oncol200927223524119064974

- DelahuntBChevilleJCMartignoniGMembers of the ISUP Renal Tumor PanelThe International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grading system for renal cell carcinoma and other prognostic parametersAm J Surg Pathol201337101490150424025520

- LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJThe PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaborationJ Clin Epidemiol20096210e1e3419631507

- HaydenJAvan der WindtDACartwrightJLCôtéPBombardierCAssessing bias in studies of prognostic factorsAnn Intern Med2013158428028623420236

- ZhangHLiuYXieHHigh mucin 5AC expression predicts adverse postoperative recurrence and survival of patients with clear-cell renal cell carcinomaOncotarget2017835597775979028938681

- XieYMaXLiHPrognostic value of clinical and pathological features in Chinese patients with chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: a 10-year single-center studyJ Cancer20178173474347929151931

- WuCYHuoJPZhangXKLoss of CD15 expression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma is correlated with worse prognosis in Chinese patientsJpn J Clin Oncol201747121182118829036563

- GuLLiHWangHPresence of sarcomatoid differentiation as a prognostic indicator for survival in surgically treated metastatic renal cell carcinomaJ Cancer Res Clin Oncol2017143349950827844145

- GershmanBMoreiraDMThompsonRHRenal cell carcinoma with isolated lymph node involvement: long-term natural history and predictors of oncologic outcomes following surgical resectionEur Urol201772230030628094055

- ChipolliniJAbelEJPeytonCCPathologic predictors of survival during lymph node dissection for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: results from a multicenter collaborationClin Genitourin Cancer2018162e443e45029113770

- NguyenHoangSLiuYXuLHigh mucin-7 expression is an independent predictor of adverse clinical outcomes in patients with clear-cell renal cell carcinomaTumour Biol20163711151931520127683054

- KhorLYDhakalHPJiaXTumor necrosis adds prognostically significant information to grade in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a study of 842 consecutive cases from a single institutionAm J Surg Pathol20164091224123127428737

- LeeHLeeSEByunSSKimHHKwakCHongSKPreoperative plasma fibrinogen level as a significant prognostic factor in patients with localized renal cell carcinoma after surgical treatmentMedicine2016954e262626825920

- KaraOMauriceMJZargarHPrognostic implications of sarcomatoid and rhabdoid differentiation in patients with grade 4 renal cell carcinomaInt Urol Nephrol20164881253126027215555

- JeonHGChoiDKSungHHPreoperative prognostic nutritional index is a significant predictor of survival in renal cell carcinoma patients undergoing nephrectomyAnn Surg Oncol201623132132726045392

- ErrartePGuarchRPulidoRThe expression of fibroblast activation protein in clear cell renal cell carcinomas is associated with synchronous lymph node metastasesPLoS One20161112e016910528033421

- YuXGuoGLiXRetrospective analysis of the efficacy and safety of sorafenib in Chinese patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and prognostic factors related to overall survivalMedicine20159434e136126313773

- SchiavinaRBorghesiMChessaFThe prognostic impact of tumor size on cancer-specific and overall survival among patients with pathologic T3a renal cell carcinomaClin Genitourin Cancer2015134e235e24126174224

- PsutkaSPBoorjianSALohseCMThe association between met-formin use and oncologic outcomes among surgically treated diabetic patients with localized renal cell carcinomaUrol Oncol2015332673e15e23

- LeeHWJeonHGJeongBCDiagnostic and prognostic significance of radiologic node-positive renal cell carcinoma in the absence of distant metastases: a retrospective analysis of patients undergoing nephrectomy and lymph node dissectionJ Korean Med Sci20153091321132726339174

- KimTZargar-ShoshtariKDhillonJUsing percentage of sarcomatoid differentiation as a prognostic factor in renal cell carcinomaClin Genitourin Cancer201513322523025544725

- WeissVLBraunMPernerSPrognostic significance of venous tumour thrombus consistency in patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC)BJU Int2014113220921724053185

- TengJGaoYChenMPrognostic value of clinical and pathological factors for surgically treated localized clear cell renal cell carcinomaChinese Med J2014127916401644

- HaddadAQWoodCGAbelEJOncologic outcomes following surgical resection of renal cell carcinoma with inferior vena caval thrombus extending above the hepatic veins: a contemporary multicenter cohortJ Urol201419241050105624704115

- El-MokademIFitzpatrickJBondadJChromosome 9p deletion in clear cell renal cell carcinoma predicts recurrence and survival following surgeryBr J Cancer201411171381139025137021

- ToscoLVan PoppelHFreaBGregoraciGJoniauSSurvival and impact of clinical prognostic factors in surgically treated metastatic renal cell carcinomaEur Urol201363464665223041360

- KruckSEyrichCScharpfMImpact of an altered Wnt1/β-catenin expression on clinicopathology and prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinomaInt J Mol Sci2013146109441095723708097

- KondoTIkezawaETakagiTNegative impact of papillary histological subtype in patients with renal cell carcinoma extending into the inferior vena cava: single-center experienceInt J Urol201320111072107723421632

- VolpeANovaraGAntonelliAChromophobe renal cell carcinoma (RCC): oncological outcomes and prognostic factors in a large multicentre seriesBJU Int20121101768322044519

- SukovWRLohseCMLeibovichBCThompsonRHChevilleJCClinical and pathological features associated with prognosis in patients with papillary renal cell carcinomaJ Urol20121871545922088335

- SamehWMHashadMMEidAAAbou YousifTAAttaMARecurrence pattern in patients with locally advanced renal cell carcinoma: the implications of clinicopathological variablesArab J Urol201210213113726558015

- KuJHParkYHMyungJKMoonKCKwakCKimHHExpression of hypoxia inducible factor-1α and 2α in conventional renal cell carcinoma with or without sarcomatoid differentiationUrol Oncol201129673173719914104

- Rodríguez-CovarrubiasFCastillejos-MolinaRSotomayorMImpact of lymph node invasion and sarcomatoid differentiation on the survival of patients with locally advanced renal cell carcinomaUrol Int2010851232920693824

- PoonSAGonzalezJRBensonMCMcKiernanJMInvasion of renal sinus fat is not an independent predictor of survival in pT3a renal cell carcinomaBJU Int2009103121622162519154464

- KlatteTSaidJWde MartinoMPresence of tumor necrosis is not a significant predictor of survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: higher prognostic accuracy of extent based rather than presence/absence classificationJ Urol2009181415581564 discussion 1563–155419230920

- CoonsBJStecAAStrattonKLPrognostic factors in T3b renal cell carcinomaWorld J Urol2009271757919039590

- KwakCParkYHJeongCWSarcomatoid differentiation as a prognostic factor for immunotherapy in metastatic renal cell carcinomaJ Surg Oncol200795431732317066434

- LeeSEByunSSOhJKSignificance of macroscopic tumor necrosis as a prognostic indicator for renal cell carcinomaJ Urol20061764 Pt 113321337 discussion 1337–133816952624

- Sanchez-OrtizRFRosserCJMadsenLTSwansonDAWoodCGYoung age is an independent prognostic factor for survival of sporadic renal cell carcinomaJ Urol20041716 Pt 12160216515126777

- GuptaKMillerJDLiJZRussellMWCharbonneauCEpidemiologic and socioeconomic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a literature reviewCancer Treat Rev200834319320518313224

- ChenKLeeBLHuangHHTumor size and Fuhrman grade further enhance the prognostic impact of perinephric fat invasion and renal vein extension in T3a staging of renal cell carcinomaInt J Urol2017241515827757999

- ZhangBYThompsonRHLohseCMA novel prognostic model for patients with sarcomatoid renal cell carcinomaBJU Int2015115340541124730416

- ShuchBBratslavskyGLinehanWMSrinivasanRSarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: a comprehensive review of the biology and current treatment strategiesOncologist2012171465422234634

- MochHCubillaALHumphreyPAReuterVEUlbrightTMThe 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs–part A: renal, penile, and testicular tumoursEur Urol20167019310526935559