Abstract

Purpose

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) accounts for ~10% of leukemia cases, and its progression involves epigenetic gene regulation. This study investigated epigenetic regulation of HOTAIR and its target microRNA, miR-143, in advanced CML.

Patients and methods

We first isolated bone marrow mononuclear cells from 70 patients with different phases of CML and from healthy donors as normal control; we also cultured K562 and KCL22 cells, treated with demethylation drug; MTT assay, flow cytometry, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (MSP), Western blot, luciferase assay, RNA pull-down assay and RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay were performed.

Result

As measured by qPCR, HOTAIR expression in K562 cells, KCL22 cells, and samples from cases of advanced-stage CML increased with levels of several DNA methyltransferases and histone deacetylates, including DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, EZH2, and LSD1, and miR-143 levels were decreased and HOTAIR levels were increased. Treatment with 5-azacytidine, a DNA methylation inhibitor, decreased DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, EZH2, LSD1 mRNA, protein levels, and HOTAIR mRNA levels but increased miR-143 levels. HOTAIR knockdown and miR-143 overexpression both inhibited proliferation and promoted apoptosis in KCL22 and K562 cells through the PI3K/AKT pathway. RNA pull-down, mass spectrometry, and RIP assays showed that HOTAIR interacted with EZH2 and LSD1. A dual-luciferase assay demonstrated that HOTAIR interacted with miR-143.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate the key epigenetic interactions of HOTAIR related to CML progression and suggest HOTAIR as a potential therapeutic target for advanced CML. Furthermore, our results support the use of demethylation drugs as a CML treatment strategy.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a clonal disease characterized by the Philadelphia chromosome, which contains the BCR–ABL1 fusion gene that encodes the P210 BCR– ABL1 protein. Typically, patients with CML experience three phases: a chronic phase (CP), an accelerated phase (AP), and a blast phase (BP), where the AP and BP involve progression of the disease. Patients who progress to BP receive standard treatment similar to that used for acute leukemia; but the effect is insufficient and the patients have a poor prognosis.Citation1,Citation2 The development of CML is very complex and involves gene mutations, chromosomal variations, and epigenetic regulation of genes.Citation3

In contrast to genetic changes, epigenetic changes refer to hereditary changes in gene expression without changes in DNA sequence, such as DNA methylation, chroma tin remodeling, and histone modification.Citation4 The DNMT family, which includes DNMT1 and DNMT3A, and the HDAC family, which includes HDAC1 and HDAC2, play important roles in DNA methylation and histone deacetylation, respectively.Citation5–Citation7 DNA methylation and histone deacetylation are known to play a role in the occurrence and progression of cancers.Citation8,Citation9 However, the relationship between DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, EZH2, LSD1, and CML is unknown.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are longer than 200 nt, and they do not encode proteins.Citation10 Recent studies have reported that the lncRNA HOTAIR plays an important role in the development of not only solid tumors, such as breast cancer and non-small-cell lung cancer,Citation11–Citation14 but also hematopoietic malignancies, such as acute myeloid leukemia.Citation15,Citation16 However, the epigenetic regulation mechanisms of HOTAIR in advanced CML are unclear.

Similar to lncRNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs) do not encode proteins,Citation17 but they are <200 nt in length.Citation18,Citation19 Low levels of miR-143-3p are associated with decreased risk of ovarian cancer.Citation20 In breast cancer, miR-143-3p regulates proliferation and apoptosis by targeting MYBL2.Citation21 However, the relationship between miRNA and CML blast crisis is largely unknown.

Patients and methods

Specimen collection

Bone marrow samples were collected from 70 patients with CML admitted to the Department of Hematology of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University between May 2016 and June 2017 (). Bone marrow samples from 10 healthy donors were used as controls. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated via lymphocyte separation. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Department of Hematology of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University, and each patient signed informed consent. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) diagnosis of CML via bone marrow morphology, immunology, molecular biology, and cytogenetic analysis; 2) clear pathological stag ing; and 3) availability of intact clinical data. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) significant organ dysfunction; 2) pregnancy; and 3) failure to provide informed consent. No chemotherapy was administered before specimens were collected.

Table 1 Characteristics of the patients included in the study

Cell culture

KCL22 and K562 cells were from Shanghai Hong Shun Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The use of K562 and KCL22 cells was confirmed by the ethics committee of the Department of Hematology of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University. KCL22 cells were cultured in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Clark Bioscience, Claymont, DE, USA), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. K562 cells were maintained in the RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin.

Cell treatment

5-Azacytidine was purchased from ApexBio (Houston, TX, USA). KCL22 and K562 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 5×106 cells/well. MTT assays were performed to measure the EC50 concentrations of 5-azacytidine. The K562 and KCL22 cells were treated with 5-azacytidine at the EC50 values. KCL22 cells were treated with 60, 80, and 100 µmol/L 5-azacytidine; K562 cells were treated with 40, 60, and 80 µmol/L 5-azacytidine. The cells were treated for 48 hours.

MTT assays

We seeded KCL22 and K562 cells into 96-well plates (1×104 cells/well) after transfection and cultured them for 0, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 hours using IMDM with 10% FBS at 37°C and RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS. Proliferation of the KCL22 and K562 cells was determined with an MTT assay. Briefly, following cell culture, 10 µL of MTT reagent (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well, and the 96-well plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for 4 hours.

Apoptosis assay

KCL22 and K562 cells were seeded into six-well plates after transfection and treated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were stained with 5 µL of Annexin V-FITC and 5 µL of propidium iodide (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and then analyzed with a BD FAC-SCanto II system (BD Biosciences). The apoptosis results were analyzed using the BD FACSDiva (BD Biosciences)

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using the RNA easy Mini Kit (Qiagen NV, Venlo, the Netherlands), and the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to synthesize cDNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction was performed at 42°C for 60 minutes, followed by 25°C for 5 minutes and finally 70°C for 5 minutes. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification was performed in 20 µL final volumes containing 1 µL of template cDNA, 1 µL of sense primer, 1 µL of antisense primer, 10 µL of SYBR Green Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 8 µL of DEPC-treated water. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed using an ABI 7500 real-time rotary analysis system (American BioInnovations, Sparks, MD, USA). Real-time PCR primer sequences are shown in . For each run, each reaction was repeated independently at least three times. RT-PCR was performed under the following conditions: enzyme activation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 35 seconds, and 72°C for 20 seconds. The 2−ΔΔCt method was used to calculate relative gene expression.

Table 2 Primer sequences for RT-PCR

Methylation-specific PCR

DNA extraction kit (Shanghai Generay Biotech Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). DNA was stored at –80°C. Sulfite conversion of DNA was performed using the EZ DNA methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo USA, Inc., Fleming Island, FL, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For all reactions, the amplification reaction contained bisulfite-modified DNA (2 µL), ZymoTaq PreMix (12.5 µL), H2O (8.5 µL), upstream primer (1 µL), and downstream primer (1 µL). The PCR conditions were 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 35 cycles (30 seconds at 95°C, 45 seconds at 54°C for annealing, and 45 seconds at 72°C) and a final extension step of 7 minutes at 72°C. The primers were designed according to reference documents (Oka et al, 2001), and the original cDNA sequences were checked in the gene pool. The PCR products after 2% agarose gel electrophoresis (GoldView; Saibaisheng Bioengineering Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) were as follows: HOTAIR methylated (M) and HOTAIR unmethylated (U) positive–negative methylation, HOTAIR M and HOTAIR U partial methylation, and HOTAIR M and HOTAIR U positive–negative unmethylation. The primers were synthesized by Saibaisheng Bioengineering Co., Ltd., and their sequences are shown in .

Table 3 Primer sequences of the methylated HOTAIR and miRNA-143 gene

Western blot (WB)

Cells were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer, and protein was obtained. The protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins were separated on 8%–15% SDS-PAGE gels, and the separated bands were electrotransferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat skim milk at room temperature and probed with antibodies targeting PI3K (1:1,000), AKT (1:3,000), mTOR (1:2,000), pPI3K (1:3,000), pAKT (1:3,000), pmTOR (1:1,000), EZH2 (1:2,000), LSD1 (1:2,000), DNMT1 (1:2,000), DNMT3A (1:3,000), HDAC1 (1:2,000) and ACTB (1:5,000) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). The diluted corresponding secondary antibody was incubated with the membranes at room temperature for 1 hour, and the membranes were then rinsed three times for 5 minutes each with tris-buffered saline. Protein expression was examined using a BioSpectrum Imaging System (UVP, LLC, Upland, CA, USA).

RNA pull-down assay

HOTAIR-binding proteins were determined using a Pierce Magnetic RNA-Protein Pull-Down Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. HOTAIR sense and HOTAIR antisense lncRNAs were constructed and incubated with the protein from KCL22 cells, and 100 mL of silver staining solution was added to the HOTAIR sense and HOTAIR antisense lncRNA and protein mixture. The total protein was then collected for mass spectrometry sequencing.

RNA immunoprecipitation

RNA immunoprecipitation was performed using the Magna RIP Kit (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Complete KCL22 cell lysates were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and contained phosphatase and proteinase inhibitors. Next, we evaluated the connection and configuration of the antibody beads, antibody beads suspension was mixed with the sample after thawing and placed on a table at 4°C for overnight incubation. Immunoprecipitation was completed after the suspension was placed on the magnetic frame and washed with washing buffer at least six times. Finally, the immune co-precipitation products were collected, and RNA was extracted and purified to determine the abundance of the target RNA.

Luciferase assay

In the dual-luciferase assay, we seeded HOTAIR and negative control (NC) cells into 24-well plates and co-transfected the cells with 0.4 mg of firefly luciferase reporter vector, 0.08 mg of Renilla luciferase pRL-TK (Promega Corporation, Fitchburg, WI, USA), and control vector according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At 48 hours after transfection, the cells were lysed. Luciferase activity was measured by a dual-luciferase reporter gene assay system (Promega Corporation). Renilla luciferase activity was determined relative to the standardized fluorescence activity of firefly luciferase. All assays were repeated at least three times.

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as mean±SD and were analyzed using SPSS 19.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Significant differences between groups were analyzed using Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA for more than two subgroups. The chi-squared test was applied to compare rates, and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

mRNA expression and protein levels in patients with CML

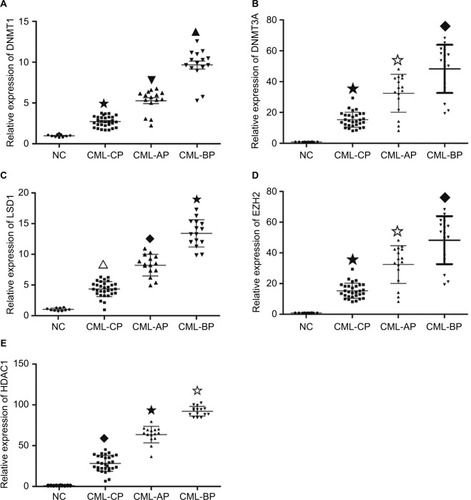

Expression levels of DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, HOTAIR, EZH2, and LSD1 were higher in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (P<0.05), whereas miR-143 expression was lower in patients with advanced-stage CML (P<0.05). The highest levels of DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, HOTAIR, EZH2, and LSD1 were found in BP CML ( and ). The advanced stage of CML was associated with a high mRNA level of DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, HOTAIR, EZH2, and LSD1 and a low level of miR-143.

Figure 1 mRNA level in different phases of CML and healthy donors.

Notes: mRNA levels were assayed by RT-qPCR. (A) DNMT1 level was higher in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (★▼▲ P<0.05, ★▼◆ P<0.05). (B) DNMT3A mRNA level was higher in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (★✩◆ P<0.05, ▼◆★P<0.05). (C) The mRNA level of LSD1 was higher in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (∆◆★P<0.05). (D) The level of EZH2 was higher in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (★✩◆P<0.05). (E) The HDAC1 mRNA level was higher in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (◆★✩P<0.05).

Abbreviations: AP, accelerated phase; BP, blast phase; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CP, chronic phase; NC, negative control; RT-qPCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

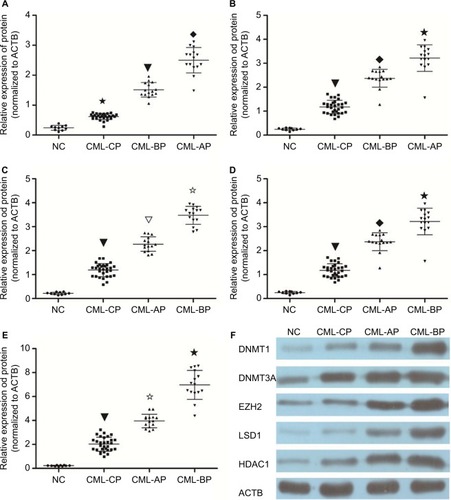

Protein levels of DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, EZH2, and LSD1 were determined in the bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMCs) of patients with different phases of CML and healthy donors. Patients with chronic-phase CML exhibited lower DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, EZH2, and LSD1 levels than patients with accelerated or BP CML (P<0.05). The highest DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, EZH2, and LSD1 protein levels were found in BP CML (). The advanced stage of CML was associated with a high protein level of DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, EZH2, and LSD1.

Figure 2 Protein level in different phases of CML and healthy donors.

Notes: Protein levels were assayed by WB. (A) DNMT1 protein level was higher in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (★▼◆ P<0.05). (B) DNMT3A protein level was higher in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (▼◆★ P<0.05). (C) Protein level of HDAC1 was higher in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (▼▽✩ P<0.05). (D) Protein level of LSD1 was higher in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (▼◆★ P<0.05). (E) EZH2 protein level was higher in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (▼✩★ P<0.05). (F) Protein expression in bone marrow (BM) cells from CML patients and normal controls. Protein expression level was determined by immunoblotting with ACTB (b-actin) as a control.

Abbreviations: AP, accelerated phase; BP, blast phase; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CP, chronic phase; NC, negative control; WB, Western blot.

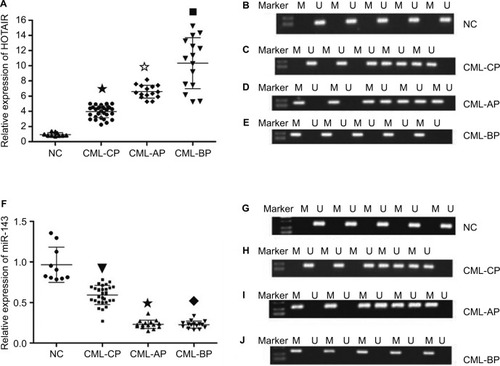

Methylation status of the HOTAIR promoter in different stages of CML

HOTAIR promoters were detected by methylation-specific PCR in different phases of CML and healthy donors. HOTAIR promoters were not detected in healthy donors and were detected in only four of 20 patients with CP CML and in all patients with AP and BP CML. The rate of methylation was higher in AP and BP CML than in CP CML or in healthy donors (P<0.05), and there was no significant difference in methylation rates between CP CML and healthy donors (P>0.05; ). The advanced stages of CML were associated with a high methylation rate.

Figure 3 The mRNA level and methylation statue of HOTAIR and miR143 in different phases of CML.

Notes: (A) mRNA level of HOTAIR was higher in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (★✩■ P<0.05). (B) The methylation rate of HOTAIR in the NC group was 0. (C) The methylation rate of HOTAIR in CML-CP was 20%. (D and E) All (100%) of the samples for patients with disease progression (CML-AP + CML-BP) were methylated compared with the normal controls and CML-CP patients, P<0.01. (F) miR-143 mRNA level was lower in AP and BP than in CP and healthy donors (▼★◆ P<0.05). (G) Methylation of miR-143 in the NC group could not be detected. (H) The methylation rate of miR-143 in CML-CP was 25%. (I and J) Methylation of miR-143 was detected in all patients with disease progression (CML-AP + CML-BP).

Abbreviations: AP, accelerated phase; BP, blast phase; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CP, chronic phase; NC, negative control.

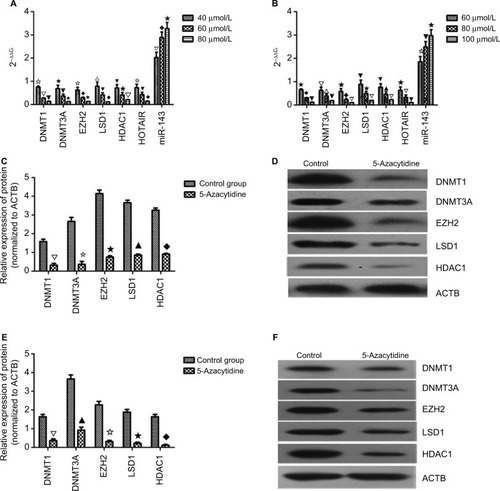

mRNA and protein levels after drug treatment

K562 and KCL22 cells were treated with different concentrations of 5-azacytidine according to the EC50 values of 5-azacytidine in these cells. K562 cells received 40, 60, and 80 µmol/L 5-azacytidine, and KCL22 cells received 60, 80, and 100 µmol/L. The mRNA and protein levels of DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, EZH2, and LSD1, as well as HOTAIR mRNA levels, decreased with 5-azacytidine treatment in a concentration-dependent fashion. The maximum mRNA levels were found in the cells treated with the lowest drug concentrations (P<0.05). miRNA-143 levels increased with treatment in a concentration-dependent manner (P<0.05; ). 5-azacytidine decreased the levels of DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, HOTAIR, EZH2, and LSD1 and increased the level of miR-143.

Figure 4 mRNA and protein level after drug treatment.

Notes: (A) In K562 cells, the mRNA level of DNMT1, DNMT3A, EZH2, LSD1, HDAC1, HOTAIR, and miR-143 was decreased in a concentration-dependent manner (✩▽▼ P<0.05, ★▼✩ P<0.05, ✩◆★ P<0.05, ∆▼◆ P<0.05, ▼★▽ P<0.05, ✩▼◆ P<0.05, ▽◆★ P<0.05). (B) In KCL22 cells, the mRNA level of DNMT1, DNMT3A, EZH2, LSD1, HDAC1, HOTAIR, and miR-143 was decreased in a concentration-dependent manner (★◆▼ P<0.05, ▽△▼ P<0.05, ★◆▽ P<0.05, ▼★▽ P<0.05, ▼▲▽ P<0.05, ★▽▼ P<0.05, ✩▼★ P<0.05). (C and D) In K562 cells, the protein level of DNMT1, DNMT3A, EZH2, LSD1, and HDAC1 was decreased in a concentration-dependent manner (∆✩★▲◆ P<0.05). (E and F) In KCL22 cells, the protein level of DNMT1, DNMT3A, EZH2, LSD1, and HDAC1 was decreased in a concentration-dependent manner (∆▲✩★◆ P<0.05).

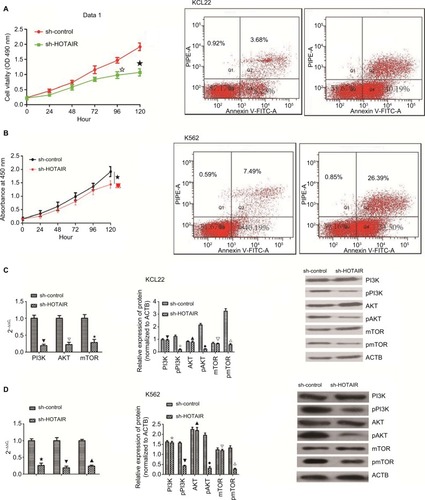

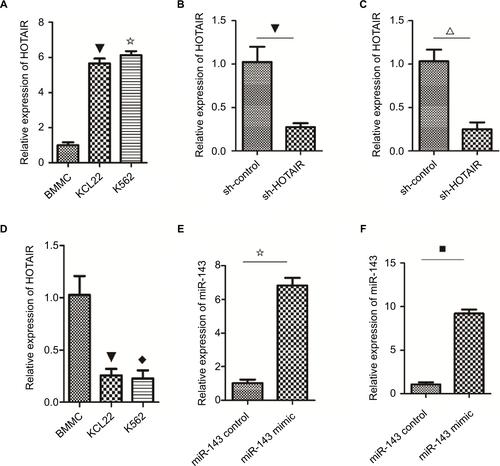

HOTAIR knockdown inhibited proliferation and promoted apoptosis

To examine the biological role of lncRNA HOTAIR in CML blast crisis, we first determined the expression of HOTAIR in BMMCs and K562 and KCL22 cells; the result indicated that the expression of HOTAIR was higher in KCL22 and K562 cells than in BMMCs (P<0.05; Figure S1A). Next, sh-HOTAIR and sh-control were synthesized and transfected into KCL22 and K562 cells; the results indicated that the expression of HOTAIR was lower in the knockdown group than in the control group (P<0.05; Figure S1B and C). HOTAIR knockdown significantly inhibited KCL22 and K562 cell proliferation (P<0.05) and promoted apoptosis (P<0.05) compared to transfection with control shRNA (). HOTAIR knockdown inhibited proliferation and promoted apoptosis.

Figure 5 Biological role of HOTAIR in K562 and KCL22.

Notes: (A) K562 cells were transfected with sh-HOTAIR and sh-control, and MTT was performed. Knockdown of HOTAIR inhibited proliferation of cells (★✩ P<0.05). Silencing of HOTAIR promoted apoptosis of KCL22 cells (P<0.05). (B) KCL22 was transfected with sh-HOTAIR and sh-control, and MTT was performed. Knockdown of HOTAIR inhibited proliferation of cells (★ P<0.05). Silencing of HOTAIR promoted apoptosis of K562 cells (P<0.05) (C) In KCL22 cells, the PI3K, AKT, and mTOR mRNA level was decreased in the knockdown group (▼∆★ P<0.05). In KCL22 cells, silencing of HOTAIR had no effect on the total protein level of PI3K, AKT, and mTOR (▼▲∆ P>0.05) but decreased phosphorylated protein levels of PI3K, AKT, and mTOR (✩◆△ P<0.05). (D) In K562 cells, the PI3K, AKT, and mTOR mRNA levels were decreased in the knockdown group (★▼▲ P<0.05). In K562 cells, silencing of HOTAIR had no effect on the total protein level of PI3K, AKT, and mTOR (✩▲∆ P>0.05) but decreased phosphorylated protein levels of PI3K, AKT, and mTOR (▼◆△ P<0.05).

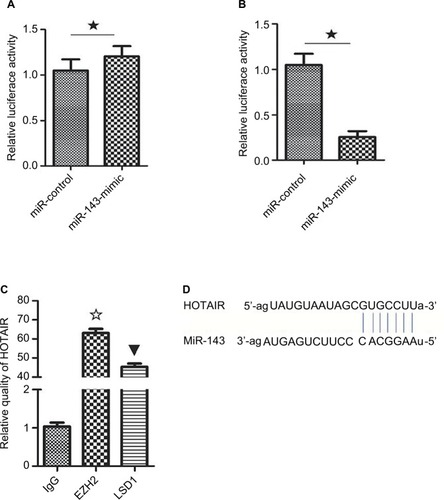

HOTAIR interacts with miR-143

Competing endogenous RNAs are lncRNAs that act as sponges to bind miRNAs and prevent them from performing normal regulatory activities. To investigate whether HOTAIR acts in this way, a luciferase reporter assay was performed to determine whether HOTAIR binds miR-143. The results indicated that transfection with miR-143 mimic decreased the luciferase activity of HOTAIR wild-type plasmids in KCL22 cells (P<0.05; ) but had no effect on mutant-type plasmids (P>0.05; ). HOTAIR was able to interact with miR-143 ().

Figure 6 HOTAIR act as a ceRNA for miR143.

Notes: (A) Luciferase reporter plasmids containing the mutant HOTAIR (MUT-HOTAIR) sequence were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells with miR-143 mimics or their corresponding NCs. There was no significant difference in luciferase activity between the miR-143 mimic group and the negative control group (★ P>0.05). (B) WT-HOTAIR was co-transfected into HEK-293T cells with miR-143 mimic or negative control. Luciferase activity was lower in the miR-143 mimic group compared with that in the negative control group (★ P<0.05). (C) RIP-PCR was performed to verify that LSD1 and EZH2 bind HOTAIR (✩▼ P<0.05). (D) miR-143 was a target of HOTAIR.

Abbreviations: MUT-HOTAIR, mutant HOTAIR; NC, negative control; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RIP, RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation; WT, wild type.

HOTAIR interacts with EZH2 and LSD1

To determine whether the lncRNA HOTAIR binds protein, RNA pull-down and RIP assays were performed. The results showed that EZH2 and LSD1 interacted with the HOTAIR lncRNA (P<0.05; ). EZH2 and LSD1 were able to interact with HOTAIR.

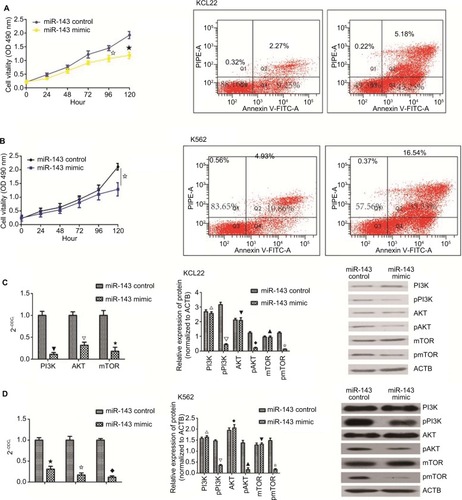

Overexpression of miR-143 inhibited proliferation and promoted apoptosis

To examine the influence of miR-143 on cell proliferation and apoptosis of KCL22 and K562, we first measured miR-143 expression levels in KCL22, K562, and BMMCs. The result showed that miR-143 expression levels were lower in KCL22 and K562 cells than in BMMCs (Figure S1D). Next, the miR-143 mimic was transfected into KCL22 and K562 cells (Figure S1E and F); proliferation assays were performed to assess the influence of miR-143 on proliferation of KCL22 and K562 cells. We found that cell viability of KCL22 cells decreased 96 and 120 hours after transfection with the miR-143 mimic (P<0.05; ), whereas that of K562 cells was reduced 120 hours after transfection with the miR-143 mimic (P<0.05; ). Flow cytometry was then performed to determine the influence of miR-143 on KCL22 and K562 apoptosis; the results indicated that miR-143 overexpression promoted apoptosis (P<0.05; ). Overexpression of miR-143 inhibited proliferation and promoted apoptosis

Figure 7 The biological role of miR143 in K562 and KCL22.

Notes: (A) K562 cells were transfected with miR-143 mimic and miR-143 control. MTT assay was performed, and overexpression of miR-143 inhibited cell proliferation (✩★ P<0.05). Overexpression of miR-143 promoted apoptosis in KCL22 cells (P<0.05). (B) KCL22 cells were transfected with miR-143 mimic and miR-143 control. MTT assay was performed; overexpression of miR-143 inhibited cell proliferation (✩ P<0.05). In K562 cells, overexpression of miR-143 promoted apoptosis (P<0.05). (C) In KCL22 cells, PI3K, AKT, and mTOR mRNA levels were decreased in the overexpression group (▼∆✩ P<0.05). In KCL22 cells, overexpression of miR-143 had no effect on total PI3K, AKT, and mTOR protein levels (△▼▲ P>0.05) but decreased phosphorylated PI3K, AKT, and mTOR protein levels (∆◆✩ P<0.05). (D) In K562 cells, PI3K, AKT, and mTOR mRNA levels were decreased in the overexpression group (★✩◆ P<0.05); in K562 cells, overexpression of miR-143 had no effect on total PI3K, AKT, and mTOR protein levels (△◆▼ P>0.05) but decreased phosphorylated PI3K, AKT, and mTOR protein levels (∆▲✩ P<0.05). CML accounts for ~10% of all types of leukemia, and although it can occur in any age group, it most often occurs in patients aged 55–70 years. The incidence of CML is higher in males than in females.Citation1 The Philadelphia chromosome, characterized by the presence of the BCR–ABL1 fusion gene, is the most common chromosomal abnormality in CML. This fusion gene encodes a constitutively active tyrosine kinase signaling protein; this uncontrolled activity leads to CML.Citation22

Both knockdown of HOTAIR and overexpression of miR-143 influence the PI3K/AKT pathway

PCR and WB were performed to assess the influence of miR-143 and HOTAIR on the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. The results demonstrated that silencing of HOTAIR and overexpression of miR-143 decreased PI3K/AKT pathway mRNA levels (P<0.05) and had no effect on total PI3K/AKT pathway protein levels (P>0.05), but decreased levels of phosphorylated PI3K/AKT pathway proteins (P<0.05; and ). Both knockdown of HOTAIR and overexpression of miR-143 influenced phosphorylated PI3K/AKT pathway proteins.

Discussion

CML accounts for ~10% of all types of leukemia, and although it can occur in any age group, it most often occurs in patients aged 55-70 years. The incidence of CML is higher in males than in females.Citation1 The Philadelphia chromosome, characterized by the presence of the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, is the most common chromosomal abnormality in CML. This fusion gene encodes a constitutively active tyrosine kinase signaling protein; this uncontrolled activity leads to CML.Citation22 Although tyrosine kinase inhibitors have improved the 5-year survival rate of CML, some patients, due to drug resistance or an inability to tolerate tyrosine kinase inhibitors, still progress to AP and BP of CML.Citation23 Epigenetic gene regulation and noncoding RNA take part in this progression.Citation24

As a noncoding RNA, the lncRNA HOTAIR encodes no protein. It promotes proliferation of cervical cancer by targeting miR-143 and proliferation of breast cancer by upregulating Bcl-w.Citation25,Citation26 HOTAIR-mediated DNA methylation contributes to the progress of osteosarcoma by targeting miR126.Citation27 In our study, high levels of the HOTAIR were found in advanced stages of CML and were inversely proportional to miR-143 levels. We also found higher methylation promoter rates of HOTAIR and miR-143 in advanced CML. Thus, we speculated that high levels of HOTAIR lncRNA, low levels of miR-143, and higher methylation promoter rates of HOTAIR and miR-143 were associated with CML progression.

Methylation of DNA at CpG islands and histone modification are two mechanisms that lead to gene silencing, which affects the gene promoter.Citation4 The DNMT family, which includes DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, mediates CpG island methylation,Citation7 and the HDAC family regulates histone deacetylation.Citation28 The discovery of LSD1 was an important step in epigenetics research; methylation and other chemical modifications of histone lysine are dynamic regulatory processes. LSD1 has been accepted as an important prognostic factor in hepatocellular carcinoma and breast cancer.Citation29,Citation30 EZH2 belongs to polycomb repressive complex 2,Citation31 is highly conserved, and can inhibit the transcription of downstream target genes. High levels of EZH2 are associated with poor prognosis in many types of cancer, such as hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic cancer.Citation32,Citation33

Therefore, we examined DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, EZH2, and LSD1 mRNA and protein levels in different phases of CML and in healthy donors. We also measured the mRNA levels of HOTAIR and miR-143 in different phases of CML and in healthy donors. The results indicated that mRNA and protein levels of DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDAC1, EZH2, and LSD1 were higher in advanced CML and that mRNA levels of HOTAIR were higher and levels of miR-143 were lower in advanced CML. Thus, we concluded that high levels of EZH2 and LSD1 at least partly account for CML progression.

Next, we treated K562 and KCL22 cells with different concentrations of 5-azacytidine. Treatment increased miR-143 levels and decreased levels of DNMT1, DNMT3A, HDCA1, EZH2, LSD1, and HOTAIR in both KCL22 and K562 cell lines.

To further examine the role of HOTAIR and miR-143 in CML blast crisis, we knocked down HOTAIR and overexpressed miR-143. Both modifications inhibited proliferation and promoted apoptosis in KCL22 and K562 cells. We then performed RNA pull-down and RIP assays to study the regulation of HOTAIR in KCL22 cells and observed that EZH2 and LSD1 interacted with HOTAIR. Thus, we speculated that EZH2 and LSD1 may regulate HOTAIR in CML blast crisis.

PI3K/AKT signaling plays a critical role in many hematological diseases, including acute myeloid leukemia and CML.Citation34–Citation36 Our results showed that silencing of HOTAIR and overexpression of miR-143 decreased phosphorylation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR proteins; thus, we concluded that the PI3K/AKT pathway is a target for HOTAIR and miR-143.

Conclusion

HOTAIR is a potential therapeutic target for CML blast crisis, and demethylation drugs may represent a new treatment strategy.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Natural Science Fund of Hebei province.

Supplementary material

Figure S1 The level of HOTAIR and miR143 in k562 and KCL22.

Notes: (A) The expression of HOTAIR was higher in K562 and KCL22 cells than that in BMMCs (✩▼ P<0.05). (B) In KCL22 cells, the expression of HOTAIR was downregulated in the knockdown group compared with the empty group (▼ P<0.05). (C) In K562 cells, the expression of HOTAIR was decreased in the knockdown group compared with the empty group (△ P<0.05). (D) The expression of miR-143 in K562 and KCL22 cells was lower than that in BMMCs (◆▼ P<0.05). (E) In K562 cells, the expression of miR-143 was upregulated in the overexpression group compared with the control group (✩ P<0.05). (F) The expression of miR-143 was higher in the overexpression group compared with the control group (■ P<0.05).

Abbreviation: BMMC, bone marrow mononuclear cell.

Author contributions

ZL conceived and designed the study and drafted the manuscript. JL reviewed the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DeiningerMWGoldmanJMMeloJVThe molecular biology of chronic myeloid leukemiaBlood200096103343335611071626

- MahonFXDeiningerMWSchultheisBSelection and characterization of BCR-ABL positive cell lines with differential sensitivity to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571: diverse mechanisms of resistanceBlood20009631070107910910924

- PedersenBHayhoeFGJAnnotation: cellular changes in chronic myeloid leukaemiaBr J Haematol19712132512564936438

- HermanJGBaylinSBGene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylationN Engl J Med2003349212042205414627790

- MaPSchultzRMHDAC1 and HDAC2 in mouse oocytes and preimplantation embryos: specificity versus compensationCell Death Differ20162371119112727082454

- MicevicGTheodosakisNBosenbergMAberrant DNA methylation in melanoma: biomarker and therapeutic opportunitiesClin Epigenetics201793428396701

- LykoFThe DNA methyltransferase family: a versatile toolkit for epigenetic regulationNat Rev Genet2018192819229033456

- Willis-MartinezDRichardsHWTimchenkoNAMedranoEERole of HDAC1 in senescence, aging, and cancerExp Gerontol201045427928519818845

- LiBWangYXuYGenetic variants in RORA and DNMT1 associated with cutaneous melanoma survivalInt J Cancer2018142112303231229313974

- KhorkovaOHsiaoJWahlestedtCBasic biology and therapeutic implications of lncRNAAdv Drug Deliv Rev201587152426024979

- LiYWangZShiHHBXIP and LSD1 scaffolded by lncRNA hotair mediate transcriptional activation by c-MycCancer Res201676229330426719542

- XueXYangYAZhangALncRNA HOTAIR enhances ER signaling and confers tamoxifen resistance in breast cancerOncogene201635212746275526364613

- PortosoMRagazziniRBrenčičŽPRC2 is dispensable for HOTAIR-mediated transcriptional repressionEMBO J201736898199428167697

- OkugawaYToiyamaYHurKMetastasis-associated long non-coding RNA drives gastric cancer development and promotes peritoneal metastasisCarcinogenesis201435122731273925280565

- ZhangXWeissmanSMNewburgerPELong intergenic non-coding RNA HOTAIRM1 regulates cell cycle progression during myeloid maturation in NB4 human promyelocytic leukemia cellsRNA Biol201411677778724824789

- SatpathyATChangHYLong noncoding RNA in hematopoiesis and immunityImmunity201542579280425992856

- AmbrosVmicroRNAs: tiny regulators with great potentialCell2001107782382611779458

- TangLChenHYHaoNBmicroRNA inhibitors: natural and artificial sequestration of microRNACancer Lett201740713914728602827

- CarèABellenghiMMatarresePGabrieleLSalvioliSMalorniWSex disparity in cancer: roles of microRNAs and related functional playersCell Death Differ201825347748529352271

- ZhangHLiWDysregulation of micro-143-3p and BALBP1 contributes to the pathogenesis of the development of ovarian carcinomaOncol Rep20163663605361027748916

- ChenJChenXMYBL2 is targeted by miR-143 3p and regulates breast cancer cell proliferation and apoptosisOncol Res Epub20171221

- GearyCGThe story of chronic myeloid leukaemiaBr J Haematol2000110121110930974

- KayasthaGKRanjitkarNGurungRThe use of Imatinib resistance mutation analysis to direct therapy in Philadelphia chromosome/BCR-ABL1 positive chronic myeloid leukaemia patients failing Imatinib treatment, in Patan Hospital, NepalBr J Haematol201717761000100728467002

- KoschmiederSVetrieDEpigenetic dysregulation in chronic myeloid leukaemia: a myriad of mechanisms and therapeutic optionsSemin Cancer Biol Epub201782

- LiuMJiaJWangXLiuYWangCFanRLong non-coding RNA HOTAIR promotes cervical cancer progression through regulating BCL2 via targeting miR-143-3pCancer Biol Ther201819539139929336659

- DingWRenJRenHWangDLong noncoding RNA HOTAIR modulates MiR-206-mediated Bcl-w signaling to facilitate cell proliferation in breast cancerSci Rep2017711726129222472

- LiXLuHFanGA novel interplay between HOTAIR and DNA methylation in osteosarcoma cells indicates a new therapeutic strategyJ Cancer Res Clin Oncol2017143112189220028730284

- RiccioANew endogenous regulators of class I histone deacetylasesSci Signal20103103e1

- LiuCLiuLChenXLSD1 stimulates cancer-associated fibro-basts to drive Notch3-dependent self-renewal of liver cancer stem-like cellsCancer Res201878493894929259010

- BouldingTMccuaigRDTanALSD1 activation promotes inducible EMT programs and modulates the tumour microenvironment in breast cancerSci Rep2018817329311580

- BlackledgeNPFarcasAMKondoTVariant PRC1 complex-dependent H2A ubiquitylation drives PRC2 recruitment and polycomb domain formationCell201415761445145924856970

- ZhouJLiuMSunHHepatomaintrinsic CCRK inhibition diminishes myeloid-derived suppressor cell immunosuppression and enhances immune-checkpoint blockade efficacyGut201867593194428939663

- LiCHXiaoZTongJHEZH2 coupled with HOTAIR to silence MicroRNA-34a by the induction of heterochromatin formation in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomaInt J Cancer2017140112012927594424

- WöhrleFUHalbachSAumannKGab2 signaling in chronic myeloid leukemia cells confers resistance to multiple Bcr-Abl inhibitorsLeukemia201327111812922858987

- ElgehamaAChenWPangJBlockade of the interaction between Bcr-Abl and PTB1B by small molecule SBF-1 to overcome imatinib-resistance of chronic myeloid leukemia cellsCancer Lett20163721828826721204

- LiuWYuWMZhangJInhibition of the Gab2/PI3K/mTOR signaling ameliorates myeloid malignancy caused by Ptpn11 (Shp2) gain-of-function mutationsLeukemia20173161415142227840422