Abstract

Objective

The roles of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the occurrence and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remain controversial. This analysis aimed to summarize the relationships between NSAIDs and HCC development.

Methods

Studies published prior to October 1, 2017, in the PubMed, Embase, Ovid, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases were systematically searched and analyzed.

Results

Eleven studies were included in this analysis. A meta-analysis of five studies revealed that aspirin use could significantly decrease the risk of HCC occurrence (hazards ratio [HR] = 0.64, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.45–0.91, P = 0.014). No significant difference was found for the use of NSAIDs (six studies) and non-aspirin NSAIDs (three studies) in HCC occurrence (HR = 0.74, 95%CI = 0.53–1.02, P = 0.064 and HR = 0.98, 95%CI = 0.87–1.12, P = 0.81, respectively). However, subgroup analysis of cohort studies demonstrated that NSAIDs significantly decreased the risk of HCC occurrence (HR = 0.58, 95%CI = 0.43–0.78, P < 0.001). HCC patients who received NSAIDs achieved better disease-free survival and overall survival compared with the non-NSAID users (HR = 0.79, 95%CI = 0.74–0.84, P<0.001 and HR = 0.60, 95%CI = 0.50–0.72, P<0.001, respectively). Additionally, a meta-analysis of two studies showed that aspirin treatment in HCC patients could significantly decrease the 2-year and 4-year mortalities (rate ratio [RR] = 0.50, 95%CI = 0.36–0.69, P < 0.001 and RR = 0.67, 95%CI = 0.45–0.998, P = 0.049, respectively). A meta-analysis of two studies showed that aspirin use was not associated with a higher risk of bleeding in HCC patients (HR = 0.71, 95%CI = 0.41–1.23, P = 0.223).

Conclusion

The use of NSAIDs, especially aspirin, is linked to a lower risk of HCC development and better survival in HCC populations. High-quality, well-designed trials should be conducted to reevaluate the relationships between NSAIDs and HCC.

Introduction

It has been reported that worldwide 70%–90% of diagnosed primary liver cancers are hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which is the fastest growing cause of cancer-related death.Citation1–Citation3 There has been a marked increase in HCC-related annual death rates in the past two decades.Citation2,Citation4 The incidence and prevalence of HCC are increasing in Western countries, where HCC is now the leading cause of death in patients with liver cirrhosis. In addition, a recent study using the SEER registry projects has shown that the incidence of HCC will continue to rise until 2030;Citation1,Citation5 that is, HCC imposes an enormous health burden worldwide.Citation3,Citation6

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, especially of aspirin, has been linked to reduced chronic inflammation and a risk of several cancers. The effects of aspirin and non-aspirin NSAIDs rely on several possible mechanisms, partly related to the inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes and prostaglandins, such as a decrease in angiogenesis and cancer cell proliferation, an increase in apoptosis, and a reduction in proinflammatory cytokine production.Citation7–Citation9 Clinically, several studies have revealed that the long-term use of NSAIDs, including aspirin, is associated with a reduced risk of cancers and better survival.Citation10–Citation13 However, for some cancers, no association was found.Citation14 Additionally, the effects of NSAIDs including aspirin were inconsistent in HCC. For example, Sitia et alCitation15 found that the effects of aspirin were present in hepatitis B virus-related carcinogenesis but not in chemical liver carcinogenesis. Sahasrabuddhe et al’s study showed that the use of aspirin alone was associated with a 41% reduced risk of developing HCC, but the risk of developing HCC in non-aspirin NSAID users remained unchanged.Citation16

The purpose of this study was to systematically review and analyze the published studies regarding the epidemiology and outcomes of HCC patients who received NSAIDs, via meta-analysis.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We searched the PubMed, Ovid, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases for studies published prior to October 1, 2017. The following medical subject terms were used: “hepatocellular carcinoma”, “liver cancer”, “liver neoplasms”, “hepatoma”, “aspirin”, “NSAIDs”, and “non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug”. Electronic searches were supplemented with manual searches of the reference lists of all retrieved review articles, primary studies, and abstracts from meetings to identify additional studies not found electronically. The literature was searched by two authors (YT and YL) independently.

Eligibility criteria

Two authors (YT and YL) independently selected the studies and discussed them with each other when inconsistencies were found. The articles that met the following criteria were included: (1) case–control, cohort studies or randomized controlled trials (RCTs), (2) subjects 18 years of age or older, and (3) availability of the hazard ratio (HR), rate ratio (RR), or odds ratio (OR) estimates, clinicopathological features or survival data of patients with HCC who received NSAIDs or aspirin. If the duration and sources of the recruited study populations overlapped by more than 30% in two or more studies by the same authors, we only included the most recent study or the study with the larger number of HCC patients.

Data extraction

Two researchers independently read the full texts and extracted the following information: publication data, study design, sample size, population, patients’ ages, controlled variables, and follow-up period.

Methodological quality assessment

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the methodological quality of all cohort or case–control publications selected in the final analysis.Citation17 The scales allocated a maximum of nine stars for the quality of selection, comparability, exposure, and outcome of the study participants.Citation18 Two authors (YT and YL) independently assessed the study quality, and any inconsistency was discussed with the review team.

Statistical analysis

Stata software version 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was used for data analysis. The effect measures of interest were the HR, RR, and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). RRs were directly considered as HR. Odds ratios (ORs) were transformed into RRs according to the formula RR = OR/[(1−P0)+(P0×OR)], where P0 stands for HCC incidence in the nonexposed group.Citation19 Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the Cochran Q test. Higgins I2 statistics were used to determine the degree of between-study heterogeneity.Citation20 Publication bias was examined by Begg’s funnel plots and Egger’s regression tests.Citation21 Sensitivity analyses were conducted to investigate the robustness of our results and to assess whether any of the included studies had a considerable influence on the results. A fixed-effects model was initially used for our meta-analyses. Since sensitivity analysis could not determine the source of heterogeneity, a random-effects model was subsequently used to accommodate the anticipated heterogeneity across studies. If a direct report of patient survival was not available,Citation22 an estimated value was derived indirectly from the Kaplan–Meier curves using Engauge Digitizer software (http://markummitchell.github.io/engauge-digitizer). A descriptive analysis was performed when the quantitative data could not be pooled. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study and patient characteristics

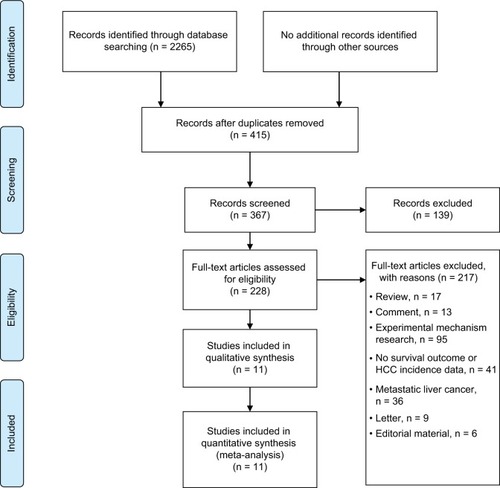

As shown in , 2265 records were identified through database searches. Overall, 228 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility after removing duplicates and screening records. Eleven studiesCitation16,Citation22–Citation31 were included in our analysis. Six studiesCitation16,Citation23–Citation27 reported the epidemiology data of NSAID use related to HCC occurrence, and fiveCitation22,Citation28–Citation31 presented survival data. The baseline characteristics of the included studies are summarized in and .

Table 1 Characteristics of studies with HCC occurrence risk data

Table 2 Baseline characteristics of studies with HCC survival outcomes

Quality assessment of included studies

The NOS quality assessment scale was used to examine potential bias risks of case control studies and cohort studies. The detailed NOS items and scores of each study are presented in . Cohort studies by Sahasrabuddhe et alCitation16 and Wu et alCitation30 did not present adjusted variables in exposed and non-exposed individuals, leading to a one-star score for comparability. We did not conduct a methodological quality assessment for the study reported in the abstract.Citation25 The study by Takami et alCitation29 was randomized and non-blinded with no patients lost to follow-up, which we considered to have a low risk of selection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias.

Table 3 NOS quality assessment of included studies (case control studies and cohort studies)

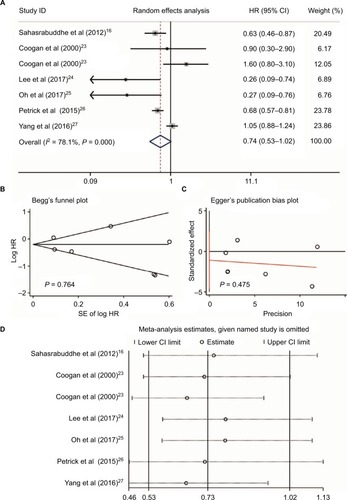

NSAIDs and HCC risk

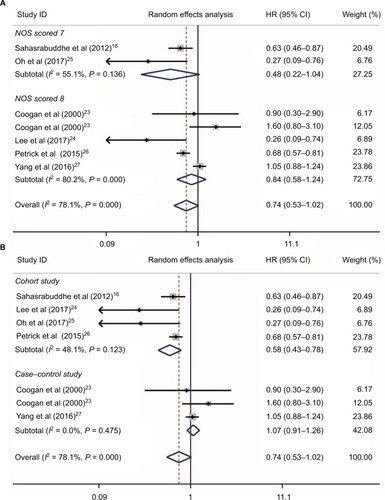

Heterogeneity was found when evaluating the association between NSAID use and HCC risk (I2 = 78.1%, P < 0.001, ). We performed a publication bias analysis and sensitivity analysis of these six studies.Citation16,Citation23–Citation27 No publication bias was found by Begg’s and Egger’s tests (P = 0.764 and P = 0.475, respectively, ). When each named study was omitted, no large influence was found in our sensitivity analysis (). Thus, a meta-analysis of six studiesCitation16,Citation23–Citation27 with the random-effect model demonstrated that patients who received NSAIDs had a similar risk of HCC occurrence compared with those without NSAIDs (HR = 0.74, 95%CI = 0.53–1.02, P = 0.064, ).

Figure 2 NSAIDs, including aspirin use and HCC risk. The use of NSAIDs, including aspirin and HCC risk (A); publication bias of included studies by Begg’s (B) and Egger’s tests (C); and sensitivity analysis of included studies (D).

Abbreviations: NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

No large influence was detected in NSAID use and HCC occurrence and, thus, we conducted further subgroup analysis based on NOS scores and study design (). As shown in , no heterogeneity was found in studies with lower NOS scores (I2 = 55.1%, P = 0.136, ), while heterogeneity was still detected in studies with high NOS scores (I2 = 80.2%, P < 0.001, ). Additionally, no significant associations were found between NSAIDs and the risk of HCC occurrence in both the groups with lower and higher NOS scores (HR = 0.48, 95%CI = 0.22–1.04, P = 0.064 and HR = 0.84, 95%CI = 0.58–1.24, P = 0.386, respectively, ). Interestingly, when we performed subgroup analysis based on study design, no heterogeneity was found in either subgroup (I2 = 48.1%, P = 0.123 and I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.475, respectively, ). Meta-analysis revealed that NSAID use could significantly decrease the HCC occurrence risk in four cohort studiesCitation16,Citation24–Citation26 (HR = 0.58, 95%CI = 0.43–0.78, P < 0.001, ), while no association between NSAIDs and HCC risk was found in case–control studiesCitation23,Citation27 (HR = 1.07, 95%CI = 0.91–1.26, P = 0.402, ). Therefore, we assumed that the study design contributed to heterogeneity, and well-designed trials should be considered to evaluate the relationships between NSAIDs and HCC risk.

Figure 3 Subgroup analysis of links between NSAIDs and HCC risk based on NOS scores (A) and study design (B).

Abbreviations: NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

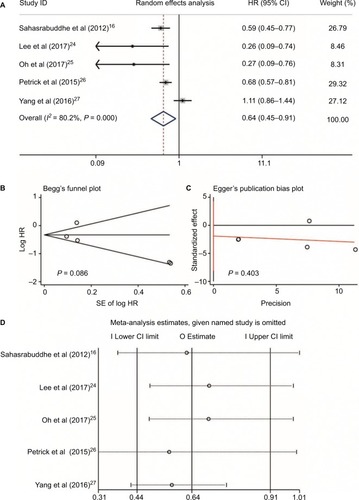

Five studiesCitation16,Citation24–Citation27 reported aspirin use and risk of HCC occurrence. Heterogeneity was found (I2 = 80.2%, P < 0.001, ); no publication bias was found by Begg’s and Egger’s tests (P = 0.086 and P = 0.403, respectively, ); and no large influence was found after each named study was omitted by sensitivity analysis (). Accordingly, a meta-analysis of five studies with a random-effects modelCitation16,Citation24–Citation27 with data on aspirin use and HCC risk revealed that aspirin use could significantly decrease the risk of HCC occurrence (HR = 0.64, 95%CI = 0.45–0.91, P = 0.014; ). In two studies reported by Yang et alCitation27 and Oh et al,Citation25 the dose and daily frequency of aspirin were not available. However, in the studies of Sahasrabuddhe et alCitation16 and Petrick et al,Citation26 patients with any frequency of aspirin use were included. In the study by Lee et al,Citation24 100 mg aspirin was used daily.

Figure 4 Aspirin use and HCC risk. Relationship between the use of aspirin and HCC risk (A); publication bias of included studies by Begg’s (B) and Egger’s tests (C); and sensitivity analysis of included studies (D).

Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

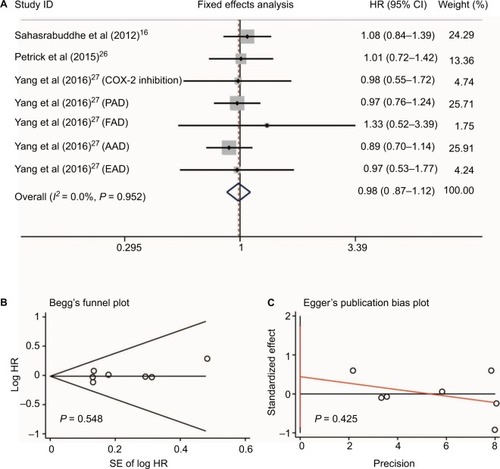

Three studiesCitation16,Citation26,Citation27 reported data on non-aspirin NSAID use and HCC risk. The non-aspirin NSAIDs in these three studies included ibuprofen,Citation26 COX-2 inhibitors (rofecoxib, celecoxib, and etoricoxib), propionic acid derivatives (ibuprofen, naproxen, ketoprofen, and tiaprofenic acid), fenamic acid derivatives (mefenamic acid), acetic acid derivatives (diclofenac, indomethacin, etodolac, and nabumetone), and enolic acid derivatives (piroxicam and meloxicam).Citation27 Since no heterogeneity was found between these three studies (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.952, ), sensitivity analysis was not conducted. Meta-analysis with a fixed-effect model showed that no significant difference was found for the use of non-aspirin NSAIDs in HCC occurrence (RR = 0.98, 95%CI = 0.87–1.12, P = 0.81; ). Additionally, no publication bias was detected by Begg’s and Egger’s tests (P = 0.548 and P = 0.425, respectively, ).

Figure 5 Non-aspirin NSAIDs use and HCC risk. Relationship between the use of non-aspirin NSAIDs and HCC risk (A); publication bias of included studies by Begg’s (B) and Egger’s tests (C).

Abbreviations: NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; PAD, propionic acid derivatives; FAD, fenamic acid derivatives; AAD, acetic acid derivatives; EAD, enolic acid (oxicam) derivatives

NSAIDs and HCC survival

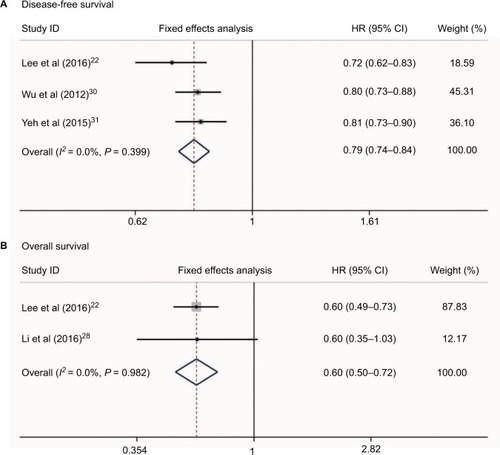

No heterogeneity was found when evaluating disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) of HCC patients who received NSAIDs (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.399 and I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.982, respectively, ). Three studiesCitation22,Citation30,Citation31 reported the DFS risk of HCC patients treated with NSAIDs. Two studiesCitation22,Citation28 presented OS data. Meta-analysis with a fixed-effect model showed that HCC patients who received NSAIDs achieved better DFS and OS compared with non-NSAID users (HR = 0.79, 95%CI = 0.74–0.84, P<0.001 and HR = 0.60, 95%CI = 0.50–0.72, P<0.001, respectively, ).

Figure 6 Relationship between NSAIDs use and disease-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) in HCC patients.

Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

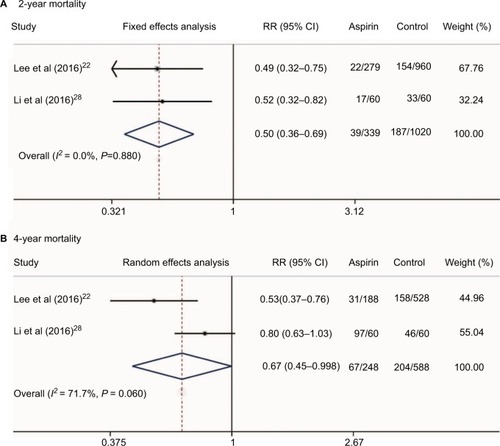

Additionally, we conducted a meta-analysis of the mortality rate of HCC patients who received aspirin treatment in two studies.Citation22,Citation28 Our results showed that aspirin treatment in HCC patients could significantly decrease the 2-year and 4-year mortalities (RR = 0.50, 95%CI = 0.36–0.69, P < 0.001 and RR = 0.67, 95%CI = 0.45–0.998, P = 0.049, respectively, ). Since only three studiesCitation22,Citation30,Citation31 presented data on NSAID use and HCC survival and two studiesCitation22,Citation28 reported data on aspirin use and HCC survival, the relationships between NSAID use and HCC clinical outcomes should be reevaluated by well-designed, large sample, multiple-centered RCTs in future.

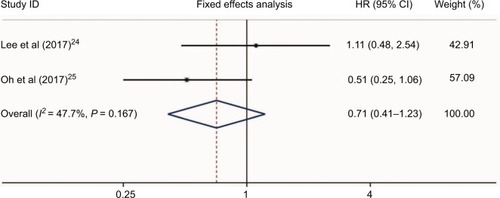

Adverse events

Two studiesCitation24,Citation28 presented the hazard risk of bleeding in HCC patients who received aspirin treatment. No heterogeneity was found (I2 = 47.7%, P = 0.167, ). Meta-analysis showed that aspirin use was not associated with a higher risk of bleeding in HCC patients (HR = 0.71, 95%CI = 0.41–1.23, P = 0.223, ). Additionally, a study by Li et alCitation28 also found no differences of bleeding risk between the aspirin group (6/60, 10%) and non-aspirin group (7/60, 11.7%) in unresectable HCC. Another study by Yeh et alCitation31 evaluated the bleeding risk of HCC in patients who received NSAIDs after curative liver resection. They found that the incidence of de novo upper gastrointestinal bleeding in NSAID users was significantly higher than that of nonusers (25.3% vs 18.7%; P < 0.001). Therefore, the bleeding risk of NSAIDs including aspirin in HCC patients still needs further evaluation.

Discussion

HCC is a type of inflammation-associated cancer;Citation32 an environment of chronic inflammation results in continuous rounds of cell injury, necrosis, and regeneration that leaves the liver prone to the development of activating mutations in oncogenes and the inactivating genetic and epigenetic suppression of tumor suppressor genes.Citation33–Citation35 Currently, anti-inflammatory therapy is effective at preventing early neoplastic progression and malignant conversion.Citation35–Citation37

NSAIDs are potential agents for chemoprevention against liver cancer based on their anti-inflammatory properties. Previous experimental studies have revealed that NSAIDs may inhibit liver cancer cellular growth and induce cell apoptosis by modifying COX enzymatic pathways, which mediate inflammation.Citation38,Citation39 Although many epidemiological studies demonstrated that treatment with NSAIDs reduces the incidence and mortality of certain malignancies, including HCC, no consistent conclusion was found.Citation23 In the studies included in our analysis, Sahasrabuddhe et alCitation16 and Petrick et alCitation26 conducted two large sample cohort studies and showed that NSAIDs were associated with an approximately 30%–40% reduced risk of developing HCC. Consistent results were also observed in patients who used aspirin. However, the risk of developing HCC remained unchanged in the users of non-aspirin NSAIDs.Citation16,Citation26 The evidence presented in these two studies is not robust enough to recommend the use of NSAIDs or aspirin in the prevention of HCC.Citation7 The case–control studies by Yang et alCitation27 and Coogan et alCitation23 showed that NSAIDs, including aspirin monotherapy and non-aspirin NSAIDs, were not associated with HCC occurrence. Oh et al’s studyCitation25 was reported as conference abstract and Lee et al’s studyCitation24 was performed in chronic hepatitis B patients on antiviral treatment, leading to the conclusion that the aspirin group showed a significantly lower risk of HCC.

This meta-analysis of cohort studies showed that NSAIDs could significantly decrease the risk of HCC occurrence. Our results showed that aspirin use could significantly reduce the risk of developing HCC. HCC patients who received NSAIDs or aspirin treatment achieved better survival compared with non-users. In vitro studies have shown that NSAIDs can potentiate apoptotic pathways by increasing death signal-associated receptors and decreasing proinflammatory signals.Citation40,Citation41 Considering the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of NSAIDs, the anti-platelet effects of aspirin and our results, we cautiously drew the conclusion that NSAIDs, especially aspirin, might be a therapeutic strategy for HCC. However, as reviewed by Sahin et al,Citation42 the pattern of COX-2 expression in HCC is different from that of other cancers. A low expression of this critical enzyme is associated with poor differentiation, whereas higher expression levels of COX-2 have been observed in well-differentiated HCC samples.Citation43,Citation44 Therefore, the exact roles of non-aspirin NSAIDs in HCC aggressiveness need to be studied further.

Previous research has demonstrated that platelets are key facilitators of this inflammation-mediated injury. The elevation of the circulating platelet count is frequently found in patients with cancerCitation45,Citation46 and is associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism and poor prognosis.Citation46,Citation47 Moreover, platelet depletion or the inhibition of platelet function has been shown to reduce or prevent cancer growth and distant metastasis in animal models.Citation15,Citation48–Citation50 Unlike other NSAIDs, aspirin has an antiplatelet effect. In an animal study, aspirin prevented HCC formation and prolonged the survival of mice with a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory liver disease by attenuating platelet-mediated inflammation.Citation15 Platelets are involved in thrombosis, inflammatory responses, liver regeneration,Citation51,Citation52 and the regulation of angiogenesis.Citation53,Citation54 In several tumor cell lines, platelets affected the epithelial-mesenchymal transition, invasion, and metastasis.Citation55 Clinical studies have shown that high platelets are involved in the extrahepatic metastasis and recurrence of HCC.Citation56–Citation58 Buergy et alCitation59 demonstrated that an elevated platelet level at the time of diagnosis was associated with a shorter survival in many solid tumors, including pancreatic adenocarcinoma, gastric cancer, and HCC. Nouso et alCitation60 recruited 157 HCC patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis and found that a high platelet level was an independent predictor of poor OS. Considering previously published reports and our results, we assumed that aspirin could decrease HCC risk and improve survival. Unfortunately, all the included studies that reported the survival data of NSAIDs were small sample, non-RCT studies. Further trials are needed in the future.

This meta-analysis has some limitations. First, most of the studies included in this analysis were not RCTs, leading to potential biases. Second, some studies included in this analysis did not report HCC risk factors, including hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus infection status. Third, the included studies that reported the survival outcomes of HCC patients who received NSAIDs had small sample sizes, and most of them included patients who received hepatic resection and might have had small HCC tumors and compensatory liver function, which poses a high risk of selection bias.

Conclusion

In summary, our results indicate that the use of NSAIDs, especially aspirin, could reduce HCC risk and improve survival in this population. Some NSAIDs have moderate selectivity for COX-1, others inhibit both COX isoforms including aspirin, indomethacin, naproxen and ibuprofen, other NSAIDs favor COX-2 inhibition, and the other ones including celecoxib, rofecoxib, lumiracoxib, valdecoxib and etoricoxib are highly selective for COX-2. Different types of NSAIDs and drug doses had different roles in the inhibition of COX-1 and COX-2.Citation61 Therefore, further studies to understand the impact of various doses and durations in the use of NSAIDs, especially aspirin intake, on the development and progression of HCC, are needed. The causal relationship between NSAIDs and HCC risk cannot be determined and further well-designed trials are required.

Acknowledgments

This work was mainly sponsored by Shanghai Sailing Program (17YF1416000), Shanghai Youth Physician Training Grant Program 2015 (to ZY), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81502059 and 81472582), and Shanghai Rising-Star Program (16QB1402900).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HeimbachJKKulikLMFinnRSAASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinomaHepatology201867135838028130846

- OmataMChengALKokudoNAsia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a 2017 updateHepatol Int201711431737028620797

- SiegelRLMillerKDJemalACancer statistics, 2017CA Cancer J Clin201767173028055103

- LozanoRNaghaviMForemanKGlobal and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010Lancet201238098592095212823245604

- PetrickJLKellySPAltekruseSFMcGlynnKARosenbergPSFuture of hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in the United States forecast through 2030J Clin Oncol201634151787179427044939

- MillerKDSiegelRLLinCCCancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016CA Cancer J Clin201666427128927253694

- KimAKDziuraJStrazzaboscoMNonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, chronic liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma: the egg of columbus or another illusion?Hepatology201358281982123703812

- HossainMAKimDHJangJYAspirin enhances doxorubicin-induced apoptosis and reduces tumor growth in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivoInt J Oncol20124051636164222322725

- FajardoAMPiazzaGAChemoprevention in gastrointestinal physiology and disease. Anti-inflammatory approaches for colorectal cancer chemopreventionAm J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol20153092G59G7026021807

- HuaXPhippsAIBurnett-HartmanANTiming of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use among patients with colorectal cancer in relation to tumor markers and survivalJ Clin Oncol201735242806281328617623

- van StaalduinenJFrouwsMReimersMThe effect of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use after diagnosis on survival of oesophageal cancer patientsBr J Cancer201611491053105927115570

- PatelDKitaharaCMParkYThyroid cancer and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use: a pooled analysis of patients older than 40 years of ageThyroid201525121355136226426828

- SkriverCDehlendorffCBorreMLow-dose aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and prostate cancer risk: a nationwide studyCancer Causes Control20162791067107927503490

- LadAAMaYLeeJANo association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and pancreatic cancer incidence and survivalPancreas2017465e43e4528426499

- SitiaGAiolfiRDi LuciaPMainettiMFiocchiAMingozziFAntiplatelet therapy prevents hepatocellular carcinoma and improves survival in a mouse model of chronic hepatitis BProc Natl Acad Sci USA201210932E2165E217222753481

- SahasrabuddheVVGunjaMZGraubardBINonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, chronic liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinomaJ Natl Cancer Inst2012104231808181423197492

- ZengXZhangYKwongJSThe methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic reviewJ Evid Based Med20158121025594108

- WellsGASheaBO’ConnellDThe Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.aspAccessed August 1, 2018

- ZhangJYuKFWhat’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomesJAMA199828019169016919832001

- HigginsJPThompsonSGQuantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysisStat Med200221111539155812111919

- EggerMDavey SmithGSchneiderMMinderCBias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical testBMJ199731571096296349310563

- LeePCYehCMHuYWAntiplatelet therapy is associated with a better prognosis for patients with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resectionAnn Surg Oncol201623Suppl 587488327541812

- CooganPFRosenbergLPalmerJRNonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of digestive cancers at sites other than the large bowelCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev20009111912310667472

- LeeMChungGELeeJHAntiplatelet therapy and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients on antiviral treatmentHepatology20176651556156928617992

- OhSShinSLeeSHAspirin and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma development in patients with compensated alcoholic cirrhosisJ Hepatol2017661S629S630

- PetrickJLSahasrabuddheVVChanATNSAID use and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: the liver cancer pooling projectCancer Prev Res (Phila)20158121156116226391917

- YangBPetrickJLChenJAssociations of NSAID and paracetamol use with risk of primary liver cancer in the Clinical Practice Research DatalinkCancer Epidemiol20164310511127420633

- LiJHWangYXieXYAspirin in combination with TACE in treatment of unresectable HCC: a matched-pairs analysisAm J Cancer Res2016692109211627725915

- TakamiYEguchiSTateishiMA randomised controlled trial of meloxicam, a Cox-2 inhibitor, to prevent hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after initial curative treatmentHepatol Int201610579980626846471

- WuCYChenYJHoHJAssociation between nucleoside analogues and risk of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence following liver resectionJAMA2012308181906191423162861

- YehCCLinJTJengLBNonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are associated with reduced risk of early hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after curative liver resection: a nationwide cohort studyAnn Surg2015261352152624950265

- BerasainCCastilloJPerugorriaMJLatasaMUPrietoJAvilaMAInflammation and liver cancer: new molecular linksAnn N Y Acad Sci2009115520622119250206

- AravalliRNSteerCJCressmanENMolecular mechanisms of hepatocellular carcinomaHepatology20084862047206319003900

- RobertsLRGoresGJHepatocellular carcinoma: molecular pathways and new therapeutic targetsSemin Liver Dis200525221222515918149

- CoussensLMWerbZInflammation and cancerNature2002420691786086712490959

- CoffeltSBde VisserKECancer: inflammation lights the way to metastasisNature20145077490484924572360

- SarvaiyaPJGuoDUlasovIGabikianPLesniakMSChemokines in tumor progression and metastasisOncotarget20134122171218524259307

- LengJHanCDemetrisAJMichalopoulosGKWuTCyclooxygenase-2 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth through Akt activation: evidence for Akt inhibition in celecoxib-induced apoptosisHepatology200338375676812939602

- FoderaDD’AlessandroNCusimanoAInduction of apoptosis and inhibition of cell growth in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by COX-2 inhibitorsAnn N Y Acad Sci2004102844044915650269

- FredrikssonLHerpersBBenedettiGDiclofenac inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced nuclear factor-kappaB activation causing synergistic hepatocyte apoptosisHepatology20115362027204121433042

- AbiruSNakaoKIchikawaTAspirin and NS-398 inhibit hepatocyte growth factor-induced invasiveness of human hepatoma cellsHepatology20023551117112411981761

- SahinIHHassanMMGarrettCRImpact of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on gastrointestinal cancers: current state-of-the scienceCancer Lett2014345224925724021750

- KogaHSakisakaSOhishiMExpression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human hepatocellular carcinoma: relevance to tumor dedifferentiationHepatology199929368869610051469

- ShiotaGOkuboMNoumiTCyclooxygenase-2 expression in hepatocellular carcinomaHepatogastroenterology1999462540741210228831

- HwangSJLuoJCLiCPThrombocytosis: a paraneoplastic syndrome in patients with hepatocellular carcinomaWorld J Gastroenterol200410172472247715300887

- StoneRLNickAMMcNeishIAParaneoplastic thrombocytosis in ovarian cancerN Engl J Med2012366761061822335738

- SimanekRVormittagRAyCHigh platelet count associated with venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: results from the Vienna Cancer and Thrombosis Study (CATS)J Thromb Haemost20108111412019889150

- GayLJFelding-HabermannBContribution of platelets to tumour metastasisNat Rev Cancer201111212313421258396

- Ho-Tin-NoeBGoergeTWagnerDDPlatelets: guardians of tumor vasculatureCancer Res200969145623562619584268

- ThunMJJacobsEJPatronoCThe role of aspirin in cancer preventionNat Rev Clin Oncol20129525926722473097

- KondoRYanoHNakashimaOTanikawaKNomuraYKageMAccumulation of platelets in the liver may be an important contributory factor to thrombocytopenia and liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis CJ Gastroenterol201348452653422911171

- StarlingerPAssingerAHaegeleSEvidence for serotonin as a relevant inducer of liver regeneration after liver resection in humansHepatology201460125726624277679

- WalshTGMetharomPBerndtMCThe functional role of platelets in the regulation of angiogenesisPlatelets201526319921124832135

- DineenSPRolandCLToombsJEThe acellular fraction of stored platelets promotes tumor cell invasionJ Surg Res2009153113213718541268

- LabelleMBegumSHynesRODirect signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasisCancer Cell201120557659022094253

- XueTCGeNLXuXLeFZhangBHWangYHHigh platelet counts increase metastatic risk in huge hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolizationHepatol Res201646101028103626776560

- LeeCHLinYJLinCCPretreatment platelet count early predicts extra-hepatic metastasis of human hepatomaLiver Int201535102327233625752212

- PangQZhangJYXuXSSignificance of platelet count and platelet-based models for hepatocellular carcinoma recurrenceWorld J Gastroenterol201521185607562125987786

- BuergyDWenzFGrodenCBrockmannMATumor-platelet interaction in solid tumorsInt J Cancer2012130122747276022261860

- NousoKItoYKuwakiKPrognostic factors and treatment effects for hepatocellular carcinoma in Child C cirrhosisBr J Cancer20089871161116518349849

- CervelloMMontaltoGCyclooxygenases in hepatocellular carcinomaWorld J Gastroenterol200612325113512116937518