Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to investigate how physical activity (PA) can be effectively promoted in cancer survivors. The effect of PA-promoting interventions in general, behavior change techniques (BCTs), and further variables as moderators in particular are evaluated.

Methods

This study included randomized controlled trials of lifestyle interventions aiming at an increase in PA that can be carried out independently at home, published by December 2016, for adults diagnosed with cancer after completion of the main treatment. Primary outcomes were subjective and objective measures of PA prior to and immediately after the intervention. Meta-analysis and meta-regression were used to estimate effect sizes (ES) in terms of standardized mean differences, variation between ES in terms of heterogeneity indices (I2), and moderator effects in terms of regression coefficients.

Results

This study included 30 studies containing 45 ES with an overall significant small positive effect size of 0.28 (95% confidence interval=0.18–0.37) on PA, and I2=54.29%. The BCTs Prompts, Reduce prompts, Graded tasks, Non-specific reward, and Social reward were significantly related to larger effects, while Information about health consequences and Information about emotional consequences, as well as Social comparison were related to smaller ES. The number of BCTs per intervention did not predict PA effects. Interventions based on the Theory of Planned Behavior were associated with smaller ES, and interventions with a home-based setting component were associated with larger ES. Neither the duration of the intervention nor the methodological quality explained differences in ES.

Conclusion

Certain BCTs were associated with an increase of PA in cancer survivors. Interventions relying on BCTs congruent with (social) learning theory such as using prompts and rewards could be especially successful in this target group. However, large parts of between-study heterogeneity in ES remained unexplained. Further primary studies should directly compare specific BCTs and their combinations.

Background

About 14.1 million new cancer cases and 8.2 million cancer-related deaths were recorded worldwide in 2012.Citation1 A person is defined as a cancer survivor from the moment of cancer diagnosis throughout life.Citation2 Early detection, improved diagnostics, and treatment have resulted in increased survival rates,Citation3,Citation4 leading to almost 32.6 million cancer survivors worldwide with a diagnosis in the previous 5 years.Citation1 Numerous disease- or treatment-related adverse effects, such as secondary cancers, fatigue, or depression, can decrease the length and quality of life.Citation5

In the last two decades it has been demonstrated that physical activity (PA) plays an important role not only in cancer prevention but also during and after cancer treatment.Citation6,Citation7 PA increases physical functioning among cancer survivors and provides physiological and psychological benefits.Citation8–Citation11 It is recommended that cancer survivors should become or stay physically active as soon as possible after diagnosis. They should engage in at least 150 minutes per week of moderately intense or 75 minutes per week of vigorous intense aerobic PA and should perform muscle-strengthening activities at least twice per week.Citation12 Despite this evidence, cancer survivors show low levels of PACitation13–Citation15 and a decline during cancer treatment without returning to PA levels prior to diagnosis.Citation16,Citation17

Changing behavior from a mainly sedentary to a physically active lifestyle poses a challenge to most people but particularly to those with chronic diseases such as cancer.Citation18,Citation19 PA that is easily performed at home (for example aerobics, walking, biking) is more convenient and accessible for patients and can play an important role in developing an active lifestyle.Citation20

Various interventions have been developed in recent years, aiming at promoting PA in cancer survivors.Citation21–Citation24 Although reviews show beneficial effects in terms of PA increasesCitation23,Citation25,Citation26 and exercise tolerance,Citation24 substantial variance in effect sizes indicates a moderating effect of intervention characteristics such as study design, theoretical foundation, and content.

Regarding study design as a moderator, a recent meta-analysis on PA promoting interventions in different target groups found a strong methodological quality to be related to smaller intervention effects.Citation27 This finding suggests that, by including methodologically weak studies with larger effects in previous meta-analyses, overall effects may potentially have been overestimated.

Theories most commonly used as a basis of behavior change interventions are the Transtheoretical Model (TTM), Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), Health Belief Model, and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB).Citation28 It is expected that interventions are more effective when built on a theoretical foundation.Citation29 However, studies show ambiguous results.Citation30,Citation31

Examining intervention content as a potential moderator is challenging, since behavior change interventions are usually built out of multiple components. To facilitate consistent classification of intervention content by researchers and clinicians, Michie et alCitation32 developed a taxonomy of behavior change techniques (BCTs) by employing a systematic expert consensus approach.Citation32 A BCT is defined as “an observable, replicable and irreducible component of an intervention designed to alter or redirect causal processes that regulate behavior”.Citation33 The taxonomy of Michie et alCitation33 (BCTT v1) consists of standardized definitions of 93 different BCTs. No consistent matching of BCT definitions from BCTT v1 with theories or theory-based determinants of PA behavior is available yet. Studies that analyzed effective BCTs in interventions to increase PACitation30,Citation31,Citation34–Citation38 showed equivocal results. Regarding cancer survivors, so far neither the amount of PA nor BCTs were compared between more or less successful trials.Citation24

The purpose of the present review and meta-analysis is to summarize the efficacy of interventions that aim at increasing overall PA that can be carried out independently at home in cancer survivors after completion of main cancer treatment and, particularly, to analyze which BCTs are most effective in this target group. Additional intervention features such as intervention duration, number of applied BCTs, and theoretical foundation as well as patient characteristics are analyzed as possible moderators of treatment effects.

Methods

To ensure correct proceedings along the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), a PRISMA checklist was created and PRISMA review guidelines were followed (Figure S1).Citation39 Every study and intervention feature was extracted by two reviewers independently and ambiguity in this process was resolved by consulting with a third reviewer. Since only published results were analyzed and no individual data gathered, no ethical approval was obtained.

Search strategy

The electronic database MEDLINE was searched for articles from the earliest possible year to December 2016. The search strategy included medical subheadings and text word terms in different combinations, for example: neoplasms, cancer survivor, exercise, PA, physical fitness, muscle strength, health promotion, health education, behavior therapy, and randomized controlled trial (RCT). The complete search strategy is shown in Figure S2. Additionally, reference lists of retrieved articles and published reviews and meta-analyses on PA interventions in cancer survivors were screened.

Study inclusion criteria

For eligibility, studies had to meet the following conditions:

Type of study: RCT. Exclusion: RCT-pilot study subsequently evaluated in a main study.

Type of participants: Adult patients (18 years of age or older) diagnosed with cancer. Exclusion: Current active treatment (except hormonal treatment) or end-of-life-care patients.

Type of intervention: Lifestyle intervention aiming at an increase in PA behavior including exercise intervention and multicomponent program focusing on PA and further lifestyle factors; interventions that aim at increasing PA that can be easily carried out independently at home. Exclusion: Interventions aiming at PA that requires professional guidance, specific equipment or facilities (eg, fitness machines).

Type of control group: Usual care or wait-list control group.

Type of outcome measure: PA (self-reported or objectively measured) prior to and immediately after the intervention. PA is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles resulting in energy expenditure.

Follow-up measurements were not taken into account, since these were reported only for a subset of interventions and were of varying duration. Only full-text articles written in English and German were included. To identify studies meeting the inclusion criteria, titles and/or abstracts of studies retrieved with the search strategy were screened. The full texts of these studies were retrieved and assessed for eligibility.

Data extraction

Extracted information of study details included author, year, research question, the country where the study was carried out, recruitment source, inclusion and exclusion criteria, study design, and description of the control group (CG) vs intervention group (IG). Regarding participant characteristics, cancer type, age, gender, and time since diagnosis or treatment were extracted. Furthermore, the following intervention details were recorded: name, frequency and total duration of the intervention, setting, type of delivery, theoretical basis, and BCTs used. Regarding PA outcome, the method of measuring PA, the number of participants randomly assigned and assessed, as well as the PA level were extracted.

Coding of methodological quality

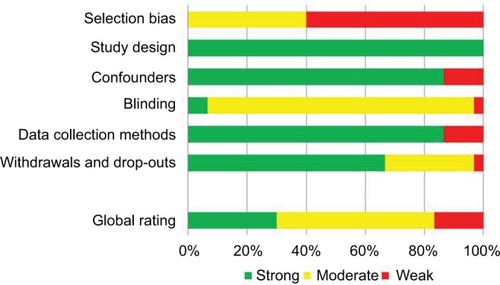

Methodological quality was assessed according to the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (EPHPP-Tool).Citation40 The tool consists of questions to help with assessing the quality concerning the six criteria selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, as well as withdrawals and dropouts, which are combined to a global rating of methodological quality. Additionally, intervention integrity and statistical analyses (including intention-to-treat approach) are evaluated.

Coding of behavior change techniques

The BCT taxonomy v1Citation32 was used to identify and code the BCTs reported in each IG. The most comprehensive published description of the intervention content (eg, from study protocols) was used. Coding was carried out by MG and EF independently after completing the BCT taxonomy v1 Online TrainingCitation41 using the given BCT definitions and coding rules. BCTs were coded as present or absent, and only the BCTs exclusively applied in the IG were extracted. After coding the first interventions, definitions and coding rules were discussed and additional coding rules established to interpret ambiguities. To quantify intercoder agreement, Cohen’s kappaCitation42 was calculated for BCTs and studies (Table S1) based on the semi-final coding after this discussion. Prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa (PABAK)Citation42 values are additionally reported. These are kappa values adjusted for a potential bias by the overall proportion of “yes”-responses as well as by differences in this proportion between the coders. Remaining disagreements in coding were then solved by discussion and consulting with a third reviewer (AE).

Data synthesis (meta-analysis and meta-regression)

Since the majority of studies reported means and standard deviations (SD or equivalents) as outcome and only a few studies reported change scores, Hedge’s g was computed as an effect size from the PA scores immediately after the intervention. Since only RCTs were included, possible baseline differences between groups should be random. For calculating SDs from other measures, formulae from the Cochrane Handbook were used.Citation43

Effect sizes and variances were calculated within the package “metafor”Citation44 for the Software RCitation45 and, where effect sizes had to be calculated from F-values, P-values or proportions, these calculations were performed with the package “compute.es”,Citation46 using conversion formulas from Cooper et al.Citation47 If required, SDs of PA outcomes following the intervention were estimated by regressing the log SDs on the log means following the Cochrane Handbook.Citation43

Available objective and self-reported measures were included, since both measure slightly different aspects of PA behavior and are only moderately correlated.Citation48,Citation49 Within-study dependencies of effect sizes were accounted for.

For studies that provided multiple self-report measures, only one effect size regarding these measures was included. Scores of total moderate to vigorous physical activity were prioritized over scores solely including low-intensity activities or those limited to only moderate or vigorous intensity activities. Overall PA was preferred over measures of sport or exercise, and measures related to total volume (ie, combining intensity, frequency, and duration) were favored over the duration of PA. Validated self-report instruments were given priority. One study did not report any measure of PA volume or frequency, but instead gave a “relative treatment effect” and the corresponding SD for both groups.Citation50 This study was included in the meta-analysis, since this outcome measure seemed directly related to overall PA, and sensitivity analysis excluding this study did not change our results meaningfully.

For studies which included different treatment conditions compared to the same CG, dependencies between effect sizes were also taken into account in the models.

Within-study covariances were estimated following Gleser and OlkinCitation51 and PustejovskyCitation52 for multiple outcomes, multiple treatment conditions, or both. In cases without a reported correlation, the estimation of covariances was based on a correlation between self-reported and objective outcomes of r=0.51, as reported for cancer survivors.Citation49 Significance tests and CIs were based on robust estimation methods to adjust for a potentially misspecified variance–covariance matrix, since all but one covariance could only be estimated.

First, a multivariate mixed effects meta-analysis (a random effects meta-analysis that allows for effect sizes of different outcomes to be correlated within a study) with the function “rma.mv” within the “metafor” package was conducted to estimate the overall effect size and between-study heterogeneity for self-reported and objective PA outcomes using the restricted maximum likelihood estimation method. Heterogeneity due to differences between the true effects was estimated by calculating a variant of I2 for multivariate meta-analysis based on a multivariate generalization of H2, as suggested by Jackson et al.Citation53 Publication bias was examined by visual inspection of the funnel plot and testing the association of study sampling variances with effect sizes within the multivariate mixed model (similar to Egger’s regression test).

To determine effects of individual BCTs, separate meta-regression models were then calculated with each BCT (coded as absent or present) as moderator. Only BCTs that were coded as being present for at least five comparisons were included. Additional models with further intervention characteristics as moderators followed the same approach.

Results

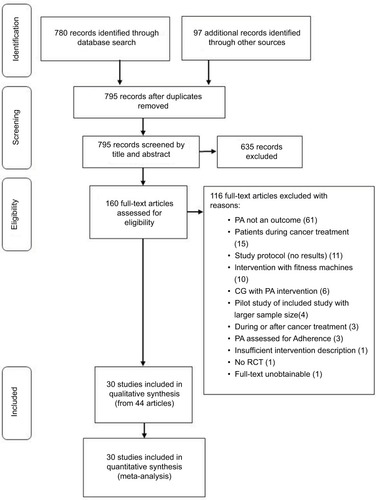

From a database search and reference checking of recent systematic reviews, 795 records were identified (). After screening, 44 articles reporting on 30 trials met the inclusion criteria.Citation54–Citation96 Of these articles, all 30 trials provided sufficient data for inclusion into the meta-analysis.

Figure 1 PRISMA flow chart of literature search for PA interventions in cancer survivors.

Abbreviations: CG, Control group; PA, physical activity; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Description of included trials

Three of the 30 RCTs included compared more than one IG to an untreated CG, resulting in the investigation of a total of 34 comparisons for self-reported PA outcomes and 11 comparisons for objectively measured PA outcomes. All studies were published between 2006 and 2016.

In total, 4,507 cancer survivors were included (M=150, range=22–641) with a mean age of 57.1 years (median (Md)=56.7, SD=7.71, range=33.6–73.1), and an overall percentage of females of M=74.14% (Md=90.93, SD=35.25, range=0%–100%). Most samples were survivors of breast cancer (k=13 trials) or mixed types of cancer (k=11). The majority of trials were from the US (k=19) and mostly used standard care as control comparison (k=21, eight wait-list control, and one not stated).

The duration of interventions ranged from one-time recommendation (zero months) to 12 months (M=4.26, Md=3, SD=2.87), and treatment took place at home (k=16), at different treatment facilities (k=4) or both combined (k=10). Study characteristics are depicted in .

Table 1 Characteristics of participants and PA interventions

Methodological quality

Results of the methodological quality assessment are presented in (for details see also Table S2). Overall, nine of the 30 studies were rated as methodologically strong, 16 as moderate, and five as weak. Regarding patient selection bias, many of the studies were rated weak (k=18), while the remaining were rated moderate. Confounders were controlled for in most of the studies (k=26). For blinding, only two of the studies were ranked strong. In the remaining studies, the blinding process was either not explained, the outcome assessors were aware of the exposure status of the participant, or the participants were aware of the research question. Reliable and valid outcome measures were used in most of the studies (k=26). Regarding drop-outs, 21 studies had a rate of less than 20%, and were, therefore, rated as strong. Nine studies had 60%–79% drop-outs, and one study did not report on drop-outs. Half of the studies (k=15) reported a sample-size calculation. Many of the studies had small sample sizes, suggesting difficulties in providing adequate statistical power to detect between-group differences, even if they were present. Intention-to-treat analyses were used in 20 studies. The remaining studies used either per-protocol analysis (k=7) or analyses were not explained (k=3).

Regarding intervention integrity (ie, the degree to which an intervention is implemented as intended), three studies reported that more than 80% of participants of the IG received the intervention, in two studies 60%–79% of participants received the intervention, while the remaining 25 studies did not communicate the information. Four studies measured the consistency of the intervention (ie, if all individuals receive the same intervention). Unfortunately, 26 studies did not report on the consistency of the intervention.

Behavior change technique coding

Overall, 41 of the 93 BCTs were coded at least once in the semi-final and 37 in the final coding. For the individual BCTs, based on the semi-final coding, Cohen’s kappa ranged from 0.30 (BCT Reduce prompts) to 1.0, with the exception of four BCTs that were coded only once or twice by one reviewer but not the other, resulting in κ=0. Including these values, mean κ was 0.76 and reflects substantial agreement.Citation97 PABAK values ranged from 0.65–1.0 (M=0.93) for the different BCTs. Regarding the different trials, Cohen’s κ ranged from 0.67–1.0 (M=0.91) and PABAK from 0.74–1.0 (M=0.94) (see Table S1). Overall, a substantial agreement could be reached.

The included interventions used an average of 10.44 BCTs (Md=11, SD=4.44), ranging from 1–17. The BCTs most commonly used were Goal setting (behavior) and Social support (unspecified) (in k=27 IGs), followed by Problem solving and Self-monitoring of behavior (k=26), Instructions on how to perform the behavior (k=24), Behavioral practice/rehearsal (k=23), and Adding objects to the environment (k=21, often related to the use of pedometers).

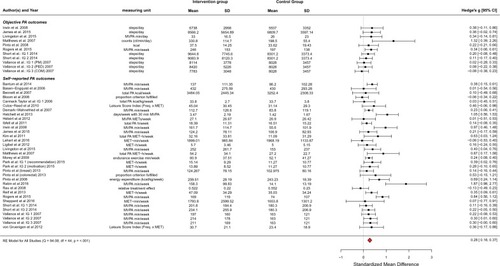

Overall meta-analysis

The meta-analysis included k=45 effect sizes (34 for self-reported, 11 for objective PA outcomes) within 30 trials. All trials used self-reported PA as an outcome and eight trials (effect sizes from 10 IGs) additionally used objectively measured PA. Raw means and SDs for the PA outcomes immediately after the intervention were extracted for 33 effects. The SD had to be estimated in eight studies (10 comparisons overall). For the prediction of SDs from log means the values R2=0.946 for the IG and R2=0.918 for the CG were detected. The estimated SDs were controlled for plausibility. In two cases the effect size was estimated based on available data, comparing group proportions by converting effect sizes to the standardized mean difference.

The funnel plot (Figure S3) and regression of effect size on sampling variance (β=3.65, t(df = 28)=2.273, P=0.031) indicated a significant asymmetry in the distribution of standard errors related to observed study outcomes mainly caused by small studies with particularly large effect sizes. The estimated pooled effect size may, therefore, be slightly overestimated. However, with a fail-safe N (number of unpublished studies with nonsignificant findings that would have to exist for the overall effect to become insignificant) of 1,859 for a probability of error of alpha=5%, an overall positive effect seems likely.

The model resulted in an overall estimated effect size in terms of standardized mean difference of g=0.276 (95% CI=0.183–0.369 based on robust variance estimation), indicating a significant effect in favor of the IG (P<0.001; ). There was significant heterogeneity of effect sizes (Q(df=44)=94.081, P<0.001), with τ2=0.048 (95% CI=0.013–0.132) for subjective outcomes and τ2=0.007 (95% CI=0.000–0.097) for objective outcomes, respectively. About 54.29% of the total variation in effect sizes was estimated to be caused by heterogeneity of true effects (I2). On average, effect sizes for self-reported PA were higher than for objective outcomes (g=0.316 as compared to 0.182, F(1,28)=4.642, P=0.040).

Figure 3 Forest plot of included studies.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COM, combination of PM and PED; IG, intervention group; MET, metabolic equivalent; MVPA, moderate to vigorous physical activity; PA, physical activity; PED, step pedometer; PM, print materials; RE model, random-effects model.

Meta-regression of PA outcomes on behavior change techniques and other potential moderators

Results of multivariate mixed effects models on BCTs

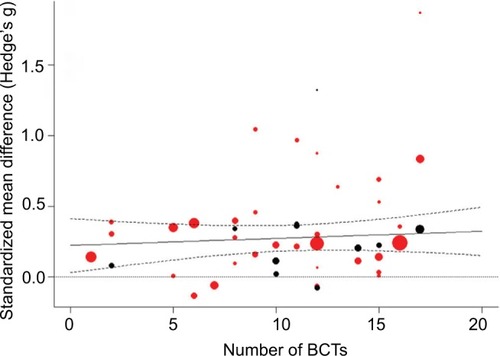

Number of BCTs

shows predicted and observed effect sizes of the included studies in relation to the number of BCTs used in the analyzed interventions. Effect sizes did not increase meaningfully with the number of BCTs per intervention (estimated increase per additional BCT, β=0.005, 95% CI=−0.007–0.017, P=0.408).

Figure 4 Prediction of effect sizes by number of BCTs.

Notes: Solid line: predicted effect size of mixed-effects model; dashed lines: 95% confidence bounds; dotted line: reference line for null effect; bubbles: individual study effect sizes with size relative to inverse variance weight; red: subjective PA outcome; black: objective PA outcome.

Abbreviations: BCTs, Behavior Change Techniques; PA, physical activity.

Moderator effects of specific BCTs

Of the final 37 BCTs exclusively applied in an IG, 27 were coded as being present for at least five effect sizes and were, therefore, analyzed as possible moderators in the meta-regression models for self-reported and objectively measured PA outcomes (see ). The BCTs Prompts/cues, Reduce prompts/cues, Graded tasks, Nonspecific reward, and Social reward were significantly related to larger effect sizes, while Information about health consequences and Information about emotional consequences as well as Social comparison were used in interventions with smaller treatment effects (P<0.05). The largest differences in effect sizes associated with the use of specific BCTs were comparable in size to the magnitude of the overall effect. With a borderline significant trend, the potential moderator Self-monitoring of behavior was associated with larger effect sizes and the moderators Discrepancy between current behavior and goal and Information about social and environmental consequences with smaller effect sizes (P<0.10).

Table 2 Results of simple meta-regression analyses with BCTs and further study characteristics as predictors of 45 effect sizes from physical activity interventions

None of these individually tested BCTs reduced the unexplained heterogeneity in effects to a nonsignificant level. Overall, the amount of heterogeneity explained by the mentioned BCTs was higher for objective than for self-reported outcomes, although the heterogeneity estimates were rather imprecise due to the small number of effect sizes for objective outcomes.

Of the seven mentioned BCTs coded most often (see “BCT coding” above), only Self-monitoring of behavior had a trend to significance while the other six BCTs were clearly not significant.

Further study characteristics analyzed as potential moderators

Intervention features

Theories that were mentioned as the foundation of interventions were analyzed as further potential moderators concerning an increase in PA (see ). Some interventions referred to more than one theory so that frequently mentioned theories were coded binary as absent or present for each study. The most frequently used theories were Social Cognitive Theory (SCT, in 25 IGs), the Transtheoretical Model (TTM, in 11), and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB, in 7), whereas seven interventions used other theories and for eight interventions no theoretical foundation was mentioned. Interventions based on the SCT reported slightly but not significantly larger effect sizes. No difference was found for interventions based on the TTM. Interventions based on the TPB revealed significantly smaller effects (P<0.001). No significant moderating effects were found for interventions that did not mention a theoretical foundation or those that were based on other theories when compared to the remaining interventions.

Table 3 Moderating effects of study and patient characteristics

Effect sizes varied with the setting of the intervention (P<0.001). Interventions that included a home-based training component seemed more effective than those that only took place at facilities like clinics or gyms, and those that combined both settings showed the largest effect sizes.

The duration of the intervention did not explain differences in effects sizes. However, effect sizes for longer interventions had a tendency to be smaller (mean effect size=0.30 for duration <3 months, 0.36 for 3 months, and 0.19 for >3 months; F(2, 27)=1.452, P=0.252).

Study characteristics

Methodological quality had no significant effect on effect size (see ). Particularly, studies with lower quality did not result in larger effect sizes. Studies published more currently reported slightly larger effect sizes with an estimated increase per year of β=0.022 (P<0.10). Effects for trials with a wait-list CG did not differ meaningfully from those with a standard care comparison.

Patient characteristics

Effect sizes had a tendency to be smaller in studies with older participants, with an estimated decrease in effect size of β=0.016 per year of mean age of the study population (P<0.10). No differential effects were found for cancer survi vors with different types of cancer, neither did the proportion of females vs males have a significant effect on outcomes.

Discussion

Within this meta-analysis, treatment effects from 30 RCTs on interventions for cancer survivors following acute treatment and aiming at an increase in PA which can be carried out independently at home were analyzed. The results show an overall significant positive effect (Hedge’s g=0.28; 95% CI=0.18–0.37) after the end of treatment, which is in line with the magnitude of effect sizes of other meta-analyses for PA interventions in cancer patients and survivors.Citation23,Citation26,Citation98 Therefore, the effect is of small magnitude in terms of established rules and typical for studies in this field.

Behavior change techniques

Our results show that some specific BCTs were associated with larger effects on PA increases. Namely, including prompts or cues to perform PA behavior (eg, adding a pedometer to a workbook as a behavioral cue) or employing intermittent telephone calls as promptsCitation79 and gradually decreasing such prompts (or the frequency/intensity of interventions) over time were significantly associated with larger PA increases. The same was true for setting graded tasks that increase in difficulty (eg, increasing the frequency and/or duration of exercise sessions from week to week was a common strategy or progressing to more demanding exercises) and for delivering different kinds of rewards for effort or progress toward PA behavior (eg, immediate reinforcement via positive automated messaging for participants who attained their personal exercise goal,Citation99 praise for achievement of goals, or progress toward goalCitation61). In general, interventions using a larger number of these specific BCTs showed larger PA increases.

In contrast, BCTs including information about the consequences of PA behavior in terms of health benefits or positive emotional effects were used in less successful interventions. Likewise, social comparison, ie, to draw attention to the performance of others compared to the patient her/himself, or emphasizing discrepancies between PA goals and actual behavior was associated with smaller intervention effects in our analysis. Combinations of more than two of these BCTs were associated with smaller PA increases.

In contrast, the overall number of BCTs used in an intervention had no significant impact on the achieved PA increase immediately after the intervention compared to standard care or wait-list controls in our study. This result is in line with meta-regressions that included BCTs to increase PA behavior in adults with obesityCitation37 or diabetes.Citation36 In contrast, Samdal et alCitation100 found more BCTs associated with larger intervention effects in overweight or obese adults.

Overall, results on the effectiveness of specific BCTs for increasing PA do not show a consistent pattern, and our analysis is only partly consistent with previous research. Rewards were associated with greater success, in line with other studies on healthy adults of the general population as well as older adults.Citation34,Citation35 However, a negative effect was found for Graded tasks in one study,Citation34 while others found a positive effect of graded tasks only on long-term but not on immediate success.Citation100 On the other hand, BCTs similar to Social comparison, which was associated with lower effect sizes in our study, showed a positive PA effect in healthy adults,Citation34 but a negative effect in a meta-analysis on older adults.Citation35 In terms of Information on consequences of the behavior, we obtained a negative association with effect size, whereas others found no effect.Citation36,Citation100 One meta-analysis showed a positive effect.Citation34 None of the compared studiesCitation30,Citation34–Citation37,Citation100,Citation101 endorse the positive effects we found in relation to Prompts and cues.

Several authors came to the conclusion that a combination of BCTs fostering self-regulation, ie, Self-monitoring, Goal setting, Feedback on performance, and Reviewing goals are especially promising in increasing PA in different populations.Citation31,Citation34,Citation38 Of these only Self-monitoring showed a marginally significant effect in our study, while no effects were found for other self-regulatory BCTs. One reason could be that cancer survivors as a specific target group react differentially to certain BCTs than other groups. This conclusion is backed by the results of French et al,Citation35 who found these techniques were not successful in older adults in contrast to younger populations. A similar mechanism could apply to Social comparison.Citation35 Social comparison might be more important for younger people than for cancer survivors or the elderly, and, thus, might not be as effective when applied as BCT in these target groups.

In addition to potential target group effects,Citation102 reasons for the differences observed may lie in different taxonomies used for coding of BCTs (ie, CALO-RE taxonomy vs BCTT v1) or in the challenge of adequate translation of intervention methods into practical application,Citation103,Citation104 as well as the varying numbers of included studies.

In our analysis, the most frequently used BCTs, including some of the self-regulatory techniques mentioned above, were not associated with a more successful PA increase. In other reviews and meta-analyses on different target groups, these or similarly defined BCTs were shown to be associated with larger PA effects (ie, Instructions on how to perform behavior,Citation34 Problem solving,Citation30,Citation35 Goal setting,Citation31,Citation100 Behavioral practiceCitation31).

One possible explanation for this finding may be that some of these BCTs were used in too many interventions to enable meaningful comparisons in our analysis. Further studies should specifically test intervention effects of such frequently employed BCTs in different target groups alone and in combination with other techniques.Citation103

Further moderators

Overall, results on the use of specific theories in PA interventions are equivocal. Most studies did not find differences between specific theories reported as the basis of PA interventionsCitation101,Citation105 or the use of theory in general.Citation27,Citation30,Citation106

Interventions that were described as based on the TPB showed lower effect sizes. Husebø et al,Citation107 on the other hand, reported that constructs of the TPB (ie, intention, perceived behavioral control) were weakly but significantly associated with better exercise adherence in eight studies with cancer patients and survivors. The most frequently stated theory in our analysis was SCT and interventions based on SCT reported slightly but not significantly larger effect sizes. While some of the identified BCTs directly match SCT constructs (like Setting graded tasks to increase self-efficacy), other techniques fitting into the SCT framework (like Role modeling) were not associated with better success.

While the authors of the present study could not identify a cluster of BCTs that completely matches one specific theory of behavior change, BCTs that proved advantageous in our study seem mostly congruent with principles of (social) learning theory, ie, rewards, including sense of achievement and situational cues which are faded out gradually and may promote habit building. In contrast, those BCTs relying on knowledge and rational decision making (ie, setting goals, providing information, problem solving) seemed less successful in increasing PA in cancer survivors. The latter is consistent with smaller effect sizes for TPB-based interventions which often rely on information and rationality.

However, in many cases it remains unclear how exactly theory is implemented in interventions. An explicit methodology for linking BCTs to theories is currently being developed and will help to clarify relations between BCTs, mechanisms of action, and other variables such as modes of delivery, populations, settings, and types of behavior.Citation33 Further research should establish whether the results of the present study can be replicated for cancer survivors compared to other groups, since this would have theoretical implications for planning interventions for this target group.

In terms of intervention duration, we did not find a meaningful effect on PA increase. A study by Bernard et alCitation27 even reports a shorter duration of theory-based interventions designed to promote PA, ie, less than 14 weeks, to be associated with larger treatment effects in different target groups. Although not significant, our results point in the same direction with the lowest effect sizes for those interventions longer than 3 months. These findings underline that duration alone may not be the best measure of overall intervention intensity and that, in fact, more complex or longer interventions do not necessarily lead to greater success.

Methodological quality of included studies was also not associated with the magnitude of intervention effects indicating that the results are not contorted by differences in study quality. In contrast, two recent studiesCitation27,Citation100 reported significant moderator effects suggesting overestimation of the efficacy of PA interventions due to methodological weaknesses. Both of these studies employed the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias,Citation108 while the present study used the EPHPP-Tool.Citation40 As Armijo-Olivo et alCitation109 demonstrated, ratings using the EPHPP-Tool may differ from those resulting from the Cochrane tool. This may explain the diverging results. However, it was also found that the EPHPP tool seems superior in terms of interrater reliability.Citation109

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study that systematically analyzed the associations of BCTs with PA increases in cancer survivors after treatment employing a current BCT taxonomy, where two coders evaluated studies independently, arriving at good interrater reliabilities. Furthermore, self-reported as well as objectively measured PA outcomes were included while adjusting the analysis for intratrial correlations.

Some limitations must also be taken into account. As our search was limited to MEDLINE, missing studies may lead to publication bias. However, we also accounted for reference lists of other current reviews and meta-analyses.Citation23,Citation98

Although the overall methodological quality of trials was not related to effect sizes, only a subset implemented an intention-to-treat analysis or reported on intervention integrity. As these criteria are not included in the overall quality rating, they may have biased the results.

Our meta-analysis is limited to outcomes measured directly after completion of interventions. Effects of specific BCTs might differ between immediate and long-term outcomes, as recently shown by Samdal et al.Citation100 Further research on long-term effects is, therefore, desirable.

Eight trials added an objectively measured PA outcome to a self-report measure. Since these trials contained more effect size information than those relying only on self-report measures, this may have influenced our results. However, including all available information by using a multivariate model and adjusting for dependencies between outcomes seemed more appropriate than including only information on self-reported measures. The overall effect size was similar to other studies on cancer survivors. Due to the limited amount of data on objective outcomes, it was not suitable to distinguish the results of meta-regression models by subjective vs objective outcome.

Peters et alCitation103 described limitations of analyzing effectiveness of BCTs by meta-analytical techniques. Within the included studies, BCTs may not have been transferred to intervention strategies effectively or may not have been adapted to target groups and contexts adequately. A prerequisite for finding an effect of BCTs in a meta-regression is the exclusive use of a BCT in the IG, but not in the CG. Since most of the included interventions only provided a very short description of the “standard care,” it was impossible to code and, therefore, detect BCTs for the CG accurately.

Effects of different BCTs may have confounded each other or may have been confounded by other study characteristics such as the overall number of BCTs applied in an intervention. Due to a large number of analyzed potential moderators compared to the limited number of included studies, calculation of more complex models allowing analyses of confounding effects were not possible.

Since some BCTs were often used in combination in the same studies (see Table S3) we adjusted for within-study dependencies of effect sizes and show “dose-response” relations for the use of those BCTs associated with effect sizes, but we cannot rule out that trial characteristics other than these BCTs were responsible for differences in PA effects. Furthermore, many BCTs were tested as moderators in separate models without adjustment for multiple testing.

Furthermore, some BCTs were used in very many or very few interventions, reducing the power of tests for moderator effects of these BCTs. A nonsignificant effect may not be interpreted as a proof of lack of effectiveness. The results are, therefore, exploratory and do not allow definite or causal conclusions.

We found some BCT definitions and coding rules not being clearly outlined and, therefore, added more specific coding rules, attaining good intercoder reliabilities afterwards. Others report similar issues.Citation100 Cradock et alCitation36 also developed extensive additional coding rules, which we included in our discussion process.

Notwithstanding these limitations, meta-analyzing the effectiveness of BCTs for increasing PA in cancer survivors and comparing the results to other target groups can be seen as one constituent of further developing theory-based interventions aimed at health behavior change in this target group.Citation103

Conclusions

A growing body of evidence shows the positive effects of PA in cancer survivors. Thus, identifying the relevant characteristics of interventions is of great importance. The present meta-analysis shows significant effects for interventions aiming at an increase in PA that can be carried out independently by cancer survivors. The magnitude of PA increase seems neither to depend on the duration of the intervention nor on the number of BCTs used, but certain techniques were associated with significantly larger or smaller PA-increasing effects. Interventions relying on BCTs congruent with (social) learning theory, such as using prompts and rewards and setting graded tasks, could be especially successful in this target group. However, large parts of between-study heterogeneity in effect sizes remained unexplained by single moderator variables. Other factors than those studied here may impact on the success of PA interventions in cancer survivors, or synergistic effects of moderators may exist that can only be revealed in more complex analyses which require larger meta-studies. To strengthen validity, the results should be replicated and in addition be complemented by the analysis of long-term effects and direct comparisons to other target groups. Further primary studies should directly test and compare specific BCTs and their combinations. Coding instruments should be more precise with an extension of definitions and anchor examples for different interventions goals.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by Stiftung Hoch-schulmedizin Dresden and by Deutsche Krebshilfe (German Cancer Aid) in the Program for the “Development of Interdisciplinary Oncology Centers of Excellence in Germany”, reference number: 107,759. We acknowledge support by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Funds of the Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden/Technische Universität Dresden. FS and NS contributed equally to this paper.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- StewartBWWildCPWorld Cancer Report 2014 online edLyonInternational Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization2014

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionCancer survivors—United States, 2007MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep201160926927221389929

- SiegelRLMillerKDJemalACancer statistics, 2017CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians201767173028055103

- Cancer Research UKCancer survival statistics Available from: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/survivalAccessed September 15, 2017

- HewittMGreenfieldSStovallEFrom Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in TransitionWashington, DCNational Academy Press2006

- SchmitzKHCourneyaKSMatthewsCAmerican College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivorsMed Sci Sports Exerc20104271409142620559064

- World Cancer Research Fund InternationalAmerican Institute for Cancer ResearchFood, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective 1. publ.Washington, DC: AICR; 2007

- SpeckRMGrossCRHormesJMChanges in the Body Image and Relationship Scale following a one-year strength training trial for breast cancer survivors with or at risk for lymphedemaBreast Cancer Res Treat2010121242143019771507

- MishraSISchererRWGeiglePMExercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivorsCochrane Database Syst Rev2012829CD007566

- BouilletTBigardXBramiCRole of physical activity and sport in oncology: scientific commission of the National Federation Sport and Cancer CAMICrit Rev Oncol Hematol2015941748625660264

- FongDYHoJWHuiBPPhysical activity for cancer survivors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsBMJ2012344 Jan 30 5e7022294757

- RockCLDoyleCDemark-WahnefriedWNutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivorsCA: A Cancer J Clin2012624242274

- LittmanAJTangM-TRossingMALongitudinal study of recreational physical activity in breast cancer survivorsJournal of Cancer Surviv201042119127

- HarrisonSHayesSCNewmanBLevel of physical activity and characteristics associated with change following breast cancer diagnosis and treatmentPsychooncology200918438739419117320

- IrwinMLCrumleyDMcTiernanAPhysical activity levels before and after a diagnosis of breast carcinoma: The Health, Eating, Activity, and Lifestyle (HEAL) studyCancer20039771746175712655532

- CourneyaKSFriedenreichCMRelationship between exercise pattern across the cancer experience and current quality of life in colorectal cancer survivorsThe Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine1997332152269430325

- DevoogdtNvan KampenMGeraertsIPhysical activity levels after treatment for breast cancer: one-year follow-upBreast Cancer Res Treat2010123241742520582717

- PintoBMCiccoloJTPhysical activity motivation and cancer survivorshipRecent Results Cancer Res201118636738721113773

- CourneyaKSKarvinenKHVallanceJKHExercise motivation and behavior changeFeuersteinMHandbook of Cancer SurvivorshipBostonSpringer US2007113132

- LeeMKKimNKJeonJYEffect of the 6-week home-based exercise program on physical activity level and physical fitness in colorectal cancer survivors: a randomized controlled pilot studyPLoS One2018134e019622029698416

- Demark-WahnefriedWJonesLWPromoting a healthy lifestyle among cancer survivorsHematol Oncol Clin North Am200822231934218395153

- PekmeziDWDemark-WahnefriedWUpdated evidence in support of diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivorsActa Oncol201150216717821091401

- BluethmannSMVernonSWGabrielKPMurphyCCBartholomewLKTaking the next step: a systematic review and meta-analysis of physical activity and behavior change interventions in recent post-treatment breast cancer survivorsBreast Cancer Res Treat2015149233134225555831

- BourkeLHomerKEThahaMAInterventions for promoting habitual exercise in people living with and beyond cancerCochrane Database Syst Rev20139CD010192

- ShortCEJamesELStaceyFPlotnikoffRCA qualitative synthesis of trials promoting physical activity behaviour change among post-treatment breast cancer survivorsJournal of Cancer Survivorship20137457058123888337

- StaceyFGJamesELChapmanKCourneyaKSLubansDRA systematic review and meta-analysis of social cognitive theory-based physical activity and/or nutrition behavior change interventions for cancer survivorsJournal of Cancer Survivorship20159230533825432633

- BernardPCarayolMGourlanMModerators of theory-based interventions to promote physical activity in 77 randomized controlled trialsHealth Education & Behavior201744222723527226432

- PainterJEBorbaCPCHynesMMaysDGlanzKThe use of theory in health behavior research from 2000 to 2005: a systematic reviewAnnals of Behavioral Medicine200835335836218633685

- GlanzKBishopDBThe role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventionsAnnu Rev Public Health201031139941820070207

- AveryLFlynnDDombrowskiSUvan WerschASniehottaFFTrenellMISuccessful behavioural strategies to increase physical activity and improve glucose control in adults with type 2 diabetesDiabetic Medicine20153281058106225764343

- GreavesCJSheppardKEAbrahamCSystematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventionsBMC Public Health201111111921333011

- MichieSRichardsonMJohnstonMThe behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventionsAnnals of Behavioral Medicine2013461819523512568

- MichieSCareyRNJohnstonMFrom theory-inspired to theory-based interventions: a protocol for developing and testing a methodology for linking behaviour change techniques to theoretical mechanisms of actionAnnals of Behavioral Medicine201636910

- WilliamsSLFrenchDPWhat are the most effective intervention techniques for changing physical activity self-efficacy and physical activity behavior–and are they the same?Health Educ Res201126230832221321008

- FrenchDPOlanderEKChisholmAMc SharryJWhich behaviour change techniques are most effective at increasing older adults’ self-efficacy and physical activity behaviour? A systematic reviewAnnals of Behavioral Medicine201448222523424648017

- CradockKAÓlaighinGFinucaneFMGainforthHLQuinlanLRGinisKAMBehaviour change techniques targeting both diet and physical activity in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysisInt J Behav Nutr Phys Act20171411828178985

- DombrowskiSUSniehottaFFAvenellAJohnstonMMacLennanGAraújo-SoaresVIdentifying active ingredients in complex behavioural interventions for obese adults with obesity-related co-morbidities or additional risk factors for co-morbidities: a systematic reviewHealth Psychol Rev201261732

- MichieSAbrahamCWhittingtonCMcAteerJGuptaSEffective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regressionHealth Psychology200928669070119916637

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGfor the PRISMA GroupPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementBMJ2009339 Jul 21 1b253519622551

- Effective Public Health Practice ProjectQuality Assessment tool for Quantitative Studies Available from: http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.htmlAccessed August 7, 2017

- BCTTv1 Online Training Available from: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/health-psychology/Accessed August 7, 2017

- ByrtTBishopJCarlinJBBias, prevalence and kappaJ Clin Epidemiol19934654234298501467

- HigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ReprChichesterWiley-Blackwell2012

- ViechtbauerWConducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor packageJ Stat Softw2010363

- R: A Language and Environment for Statistical ComputingVienna, AustriaR Foundation for Statistical Computing2015

- Del ReACcompute.es: Compute Effect Sizes: R Package version 0.2-22013 Available from: http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/compute.esAccessed June 30, 2017

- CooperHHedgesLVValentineJCThe Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-AnalysisNew YorkRussell Sage Foundation2009

- PrinceSAAdamoKBHamelMEHardtJConnor GorberSTremblayMA comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic reviewInt J Behav Nutr Phys Act2008515618990237

- BoyleTLynchBMCourneyaKSVallanceJKAgreement between accelerometer-assessed and self-reported physical activity and sedentary time in colon cancer survivorsSupportive Care in Cancer20152341121112625301224

- RauJTeichmannJPetermannFMotivation zu sportlicher Aktivität bei onkologischen Patienten nach der Rehabilitationsmaßnahme – Ergebnisse einer randomisiert-kontrollierten WirksamkeitsstudiePPmP - Psychotherapie · Psychosomatik · Medizinische Psychologie20095908300306

- GleserLJOlkinIStochastically dependent effect sizesCooperHHedgesLVValentineJCThe Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Aeta-analysisNew YorkRussell Sage Foundation2009357376

- PustejovskyJECorrelations between standardized mean differences Available from: http://jepusto.github.io/Correlations-between-SMDsAccessed August 2, 2017

- JacksonDWhiteIRRileyRDQuantifying the impact of between-study heterogeneity in multivariate meta-analysesStat Med201231293805382022763950

- BantumEOAlbrightCLWhiteKKSurviving and thriving with cancer using a web-based health behavior change intervention: randomized controlled trialJ Med Internet Res2014162e5424566820

- Basen-EngquistKTaylorCLCRosenblumCRandomized pilot test of a lifestyle physical activity intervention for breast cancer survivorsPatient Educ Couns2006641–322523416843633

- BennettJALyonsKSWinters-StoneKNailLMSchererJMotivational interviewing to increase physical activity in long-term cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trialNurs Res2007561182717179870

- BloomJRStewartSLD’OnofrioCNLuceJBanksPJAddressing the needs of young breast cancer survivors at the 5 year milestone: can a short-term low intensity intervention produce change?J Cancer Surviv20082319020418670888

- Carmack TaylorCLSmithMAde MoorCQuality of life intervention for prostate cancer patients: design and baseline characteristics of the active for life after cancer trialControl Clin Trials200425326528515157729

- Carmack TaylorCLDemoorCSmithMAActive for Life After Cancer: a randomized trial examining a lifestyle physical activity program for prostate cancer patientsPsychooncology2006151084786216447306

- Culos-ReedSNRobinsonJWLauHPhysical activity for men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: benefits from a 16-week interventionSupportive Care in Cancer201018559159919609570

- Demark-WahnefriedWClippECMcBrideCDesign of FRESH START: a randomized trial of exercise and diet among cancer survivorsMedicine & Science in Sports & Exercise200335341542412618570

- Demark-WahnefriedWClippECLipkusIMMain outcomes of the FRESH START trial: a sequentially tailored, diet and exercise mailed print intervention among breast and prostate cancer survivorsJournal of Clinical Oncology200725192709271817602076

- OttenbacherAJDayRSTaylorWCLong-term physical activity outcomes of home-based lifestyle interventions among breast and prostate cancer survivorsSupportive Care in Cancer201220102483248922249915

- HatchettAHallamJSFordMAEvaluation of a social cognitive theory-based email intervention designed to influence the physical activity of survivors of breast cancerPsychooncology201322482983622573338

- HébertJRHurleyTGHarmonBEHeineySHebertCJSteckSEA diet, physical activity, and stress reduction intervention in men with rising prostate-specific antigen after treatment for prostate cancerCancer Epidemiol2012362e128e13622018935

- IbfeltERottmannNKjaerTNo change in health behavior, BMI or self-rated health after a psychosocial cancer rehabilitation: results of a randomized trialActa Oncol201150228929821231790

- IrwinMLCadmusLAlvarez-ReevesMRecruiting and retaining breast cancer survivors into a randomized controlled exercise trial: the Yale Exercise and Survivorship StudyCancer200811211 Suppl2593260618428192

- HøybyeMTDaltonSOChristensenJResearch in Danish cancer rehabilitation: social characteristics and late effects of cancer among participants in the FOCARE research projectActa Oncol2008471475517926146

- JamesELStaceyFChapmanKExercise and nutrition routine improving cancer health (ENRICH): the protocol for a randomized efficacy trial of a nutrition and physical activity program for adult cancer survivors and carersBMC Public Health201111123621496251

- JamesELStaceyFGChapmanKImpact of a nutrition and physical activity intervention (ENRICH: Exercise and Nutrition Routine Improving Cancer Health) on health behaviors of cancer survivors and carers: a pragmatic randomized controlled trialBMC Cancer201515171026471791

- KimSHShinMSLeeHSRandomized pilot test of a simultaneous stage-matched exercise and diet intervention for breast cancer survivorsOncol Nurs Forum2011382106E106

- LahartIMMetsiosGSNevillAMKitasGDCarmichaelARRandomised controlled trial of a home-based physical activity intervention in breast cancer survivorsBMC Cancer201616123426988367

- LigibelJAMeyerhardtJPierceJPImpact of a telephone-based physical activity intervention upon exercise behaviors and fitness in cancer survivors enrolled in a cooperative group settingBreast Cancer Res Treat2012132120521322113257

- LivingstonPMSalmonJCourneyaKSEfficacy of a referral and physical activity program for survivors of prostate cancer [ENGAGE]: rationale and design for a cluster randomised controlled trialBMC Cancer201111123721663698

- LivingstonPMCraikeMJSalmonJEffects of a clinician referral and exercise program for men who have completed active treatment for prostate cancer: a multicenter cluster randomized controlled trial (ENGAGE)Cancer2015121152646265425877784

- MatthewsCEWilcoxSHanbyCLEvaluation of a 12-week home-based walking intervention for breast cancer survivorsSupportive Care in Cancer200715220321117001492

- MoreyMCSnyderDCSloaneREffects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: a randomized controlled trialJAMA2009301181883189119436015

- Demark-WahnefriedWMoreyMCSloaneRReach out to enhance wellness home-based diet-exercise intervention promotes reproducible and sustainable long-term improvements in health behaviors, body weight, and physical functioning in older, overweight/obese cancer survivorsJournal of Clinical Oncology201230192354236122614994

- SnyderDCMoreyMCSloaneRReach out to ENhancE Wellness in Older Cancer Survivors (RENEW): design, methods and recruitment challenges of a home-based exercise and diet intervention to improve physical function among long-term survivors of breast, prostate, and colorectal cancerPsychooncology200918442943919117329

- ParkJHLeeJOhMThe effect of oncologists’ exercise recommendations on the level of exercise and quality of life in survivors of breast and colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trialCancer2015121162740274825965782

- PintoBMFriersonGMRabinCTrunzoJJMarcusBHHome-based physical activity intervention for breast cancer patientsJ Clin Oncol200523153577358715908668

- PintoBMRabinCPapandonatosGDFriersonGMTrunzoJJMarcusBHMaintenance of effects of a home-based physical activity program among breast cancer survivorsSupportive Care in Cancer200816111279128918414905

- PintoBMPapandonatosGDGoldsteinMGA randomized trial to promote physical activity among breast cancer patientsHealth Psychology201332661662623730723

- PintoBMPapandonatosGDGoldsteinMGMarcusBHFarrellNHome-based physical activity intervention for colorectal cancer survivorsPsychooncology2013221546421905158

- RabinCPintoBFavaJRandomized trial of a physical activity and meditation intervention for young adult cancer survivorsJ Adolesc Young Adult Oncol201651414726812450

- ReifKde VriesUPetermannFGörresSChronische Fatigue bei KrebspatientenMed Klin201010511779786

- ReifKde VriesUPetermannFGörresSA patient education program is effective in reducing cancer-related fatigue: a multi-centre randomised two-group waiting-list controlled intervention trialEuropean Journal of Oncology Nursing201317220421322898654

- RogersLQMcAuleyEAntonPMBetter exercise adherence after treatment for cancer (BEAT Cancer) study: rationale, design, and methodsContemp Clin Trials201233112413721983625

- RogersLQCourneyaKSAntonPMEffects of the BEAT cancer physical activity behavior change intervention on physical activity, aerobic fitness, and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a multicenter randomized controlled trialBreast Cancer Res Treat2015149110911925417174

- SheppardVBHicksJMakambiKHurtado-de-MendozaADemark-WahnefriedWAdams-CampbellLThe feasibility and acceptability of a diet and exercise trial in overweight and obese black breast cancer survivors: The Stepping STONE studyContemp Clin Trials20164610611326655430

- ShortCEJamesELGirgisAMcElduffPPlotnikoffRCMove more for life: the protocol for a randomised efficacy trial of a tailored-print physical activity intervention for post-treatment breast cancer survivorsBMC Cancer201212117222569139

- ShortCEJamesELPlotnikoffRCTheory-and evidence-based development and process evaluation of the Move More for Life program: a tailored-print intervention designed to promote physical activity among post-treatment breast cancer survivorsInt J Behav Nutr Phys Act201310112424192320

- ShortCEJamesELGirgisAD’SouzaMIPlotnikoffRCMain outcomes of the Move More for Life Trial: a randomised controlled trial examining the effects of tailored-print and targeted-print materials for promoting physical activity among post-treatment breast cancer survivorsPsychooncology201524777177825060288

- VallanceJKHCourneyaKSPlotnikoffRCYasuiYMackeyJRRandomized controlled trial of the effects of print materials and step pedometers on physical activity and quality of life in breast cancer survivorsJournal of Clinical Oncology200725172352235917557948

- VallanceJKCourneyaKSTaylorLMPlotnikoffRCMackeyJRDevelopment and evaluation of a theory-based physical activity guidebook for breast cancer survivorsHealth Education & Behavior200835217418916861593

- von GruenigenVFrasureHKavanaghMBSurvivors of uterine cancer empowered by exercise and healthy diet (SUCCEED): a randomized controlled trialGynecol Oncol2012125369970422465522

- LandisJRKochGGThe measurement of observer agreement for categorical dataBiometrics1977331159174843571

- BourkeLHomerKEThahaMAInterventions to improve exercise behaviour in sedentary people living with and beyond cancer: a systematic reviewBr J Cancer2014110483184124335923

- LeeMKParkH-AYunYHChangYJDevelopment and Formative evaluation of a web-based self-management exercise and diet intervention program with tailored motivation and action planning for cancer survivorsJMIR Res Protoc201321e1123612029

- SamdalGBEideGEBarthTWilliamsGMelandEEffective behaviour change techniques for physical activity and healthy eating in overweight and obese adults; systematic review and meta-regression analysesInt J Behav Nutr Phys Act20171414228351367

- McDermottMSOliverMIversonDSharmaREffective techniques for changing physical activity and healthy eating intentions and behaviour: asystematic review and meta-analysisBr J Health Psychol201621482784127193530

- MichieSWestRBehaviour change theory and evidence: a presentation to GovernmentHealth Psychol Rev201371122

- PetersGYde BruinMCrutzenREverything should be as simple as possible, but no simpler: towards a protocol for accumulating evidence regarding the active content of health behaviour change interventionsHealth Psychol Rev20159111425793484

- KokGGottliebNHPetersGYA taxonomy of behaviour change methods: an Intervention Mapping approachHealth Psychol Rev201610329731226262912

- GourlanMBernardPBortolonCEfficacy of theory-based interventions to promote physical activity. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsHealth Psychol Rev2016101506625402606

- PrestwichASniehottaFFWhittingtonCDombrowskiSURogersLMichieSDoes theory influence the effectiveness of health behavior interventions? Meta-analysisHealth Psychology201433546547423730717

- HusebøAMLDyrstadSMSøreideJABruEPredicting exercise adherence in cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of motivational and behavioural factorsJ Clin Nurs2013221–242123163239

- HigginsJPTAltmanDGGøtzschePCThe Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trialsBMJ2011343 Oct 2d592822008217

- Armijo-OlivoSStilesCRHagenNABiondoPDCummingsGGAssessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological researchJ Eval Clin Pract2012181121820698919