Abstract

Purpose

Although several trials have demonstrated improved progression-free survival (PFS) with first-line regimens for HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (mBC), overall survival (OS) benefit is elusive. We calculated required sample sizes to power for OS using published data from recent mBC trials.

Patients and methods

Randomized superiority trials of first-line chemotherapy/targeted therapy for HER2-negative mBC including >150 patients, meeting the primary efficacy objective, and published in 2000–2018 were identified. The sample sizes required to power for PFS and OS were calculated retrospectively for each trial using observed results and study/recruitment follow-up durations (α=0.05, two-sided log-rank test, 80% power), and summarized as a factor (x) relative to actual sample size.

Results

Nine of 13 identified trials reported all information required for retrospective sample size calculation. Six had sample sizes larger than required to demonstrate a significant PFS benefit but all would have required larger sample sizes to demonstrate significant OS benefit with the observed results. In ten trials, the required sample size was ≥5-fold larger to power for OS than PFS.

Conclusion

Designing trials to test potential new treatments for HER2-negative mBC is challenging, requiring a balance of regulatory acceptability, feasibility, and realistic medical assumptions to calculate sample sizes. Powering for OS is particularly difficult in heterogeneous populations with long postprogression survival, potential crossover, heterogeneous poststudy therapy, and evolving treatment standards. Validated surrogate endpoints are critical. Ongoing trials of cancer immunotherapy (new mode of action) in triple-negative mBC (more homogeneous, shorter OS and postprogression survival, fewer treatment options) may show a new pattern.

Introduction

In metastatic breast cancer (mBC), selection of the most appropriate endpoint for clinical trials is becoming increasingly important when evaluating new first-line therapies. In HER2-positive mBC, for which a number of targeted agents exist, several trials across treatment settings have demonstrated overall survival (OS) benefits from HER2-directed therapies.Citation1 In HER2-negative mBC, however, where the target is less clear and patient selection is more challenging, progression-free survival (PFS) benefits have rarely translated into statistically significant OS benefits. To date, no Phase III trial evaluating antiangiogenic agents, cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, or poly(adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase inhibitors has shown a statistically significant OS improvement. OS is considered an unambiguous endpoint and is the global gold standard for demonstrating clinical benefit. However, extending life is not necessarily valuable if accompanied by significant quality of life (QoL) deterioration. Other disadvantages of OS as a primary endpoint are bias caused by treatment evolution during long studies, the diluting effect of crossover, numerous heterogeneous subsequent treatment lines, and the need for large patient numbers and/or long follow-up before obtaining results. This is particularly problematic in first-line trials, in which patients typically receive multiple treatment lines after progression.Citation2,Citation3 Consequently, authorities including the European Medicines Agency accept PFS as a relevant endpoint and approve drugs based on PFS benefit.

The correlation between PFS and OS appears to be less robust in settings with longer postprogression survival and/or effective subsequent therapies,Citation4–Citation6 whereas in later treatment lines, the likelihood of showing an OS benefit increases.Citation7,Citation8 However, a recent analysis of 40 randomized controlled trials in HER2-negative hormone receptor-positive mBC indicated a significant association between PFS/time to progression (TTP) and OS, irrespective of treatment line.Citation9 To explore this topic further, we used published data from contemporary HER2-negative mBC trials to calculate the sample sizes required to power for OS compared with sample sizes actually used. Based on our findings, we discuss the challenges of designing trials in HER2-negative mBC, where powering for OS is sometimes unrealistic, unfeasible, or unfundable, with the aim of improving future trial planning and design.

Design

Clinical trials were identified from a systematic search of MEDLINE (details in ) using the following criteria: randomized superiority trials; first-line chemotherapy or targeted therapy for HER2-negative mBC; >150 patients; meeting the primary efficacy objective (“positive” trials); and published in English in a peer-reviewed journal between January 1, 2000 and February 15, 2018.

The sample sizes required to power for PFS/TTP and OS were calculated retrospectively for each trial using the observed median PFS/TTP and median OS in the treatment groups for treatment effect, the actual recruitment period, and the actual total study duration (α=0.05, two-sided log-rank test, 80% power). Dropout rates were not considered for sample size calculation. nQuery Advisor (version 7.0; Statistical Solutions Ltd, Cork, Ireland) was used for sample size calculations. If information on the total study duration was missing, we chose a simple pragmatic assumption that the study period was one-third longer than the recruitment duration.

The retrospectively calculated sample sizes were summarized as a factor (x) relative to the actual sample size. x <1 would require x-fold fewer cases to show a significant benefit, whereas x >1 required x-fold more cases.

Results

Analysis data set

Thirteen trials met the selection criteria (). Of these, nine reported all information required for retrospective sample size calculation. In four reports (all published before 2006), insufficiently described study duration made it difficult or impossible to understand fully the statistical assumptions for sample size calculation. Only one trial had OS as the primary endpoint.

Table 1 Overview of trials included in the analysis. Trials are ordered according to date enrollment began (earliest first)

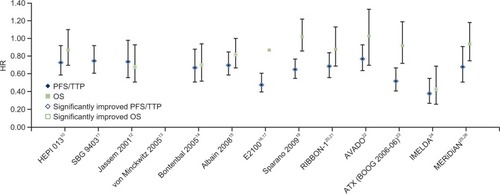

In most trials, the HRs showed a stronger treatment effect on PFS/TTP than OS (). Four trials showed statistically significantly improved OS.Citation12,Citation14,Citation15,Citation24.

Retrospective sample size calculation

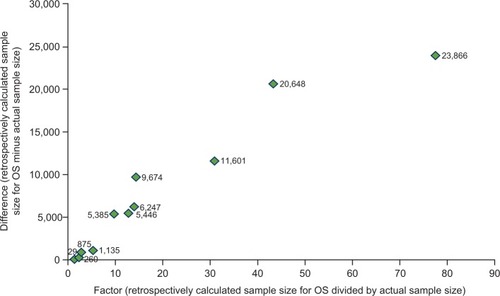

shows the retrospectively calculated sample sizes required to show PFS/TTP and OS benefit with the observed data compared with the actual sample sizes. According to these calculations, six of 13 trials had sample sizes larger than required to demonstrate a significant PFS benefit. However, all would have required a larger sample size to demonstrate a significant OS benefit with the observed results. The increase in sample size ranged from 1.2-fold to 2,460-fold. In nine of the 12 trials with OS information, the calculated required sample size to demonstrate a significant OS benefit with the observed OS results was at least fivefold greater than the actual sample size. summarizes the sample size increase required to show a significant OS benefit with the reported data.

Table 2 Summary of trial outcomes

Figure 2 Additional patients required to show an OS benefita.

Note: aOne studyCitation19 is not shown on the figure as the numbers are so large (x=2,460.2, retrospectively calculated increase in sample size =1,846,875).

Abbreviation: OS, overall survival.

In all but one trial, a larger sample size would be required to show OS than PFS benefit. In 10 of the 12 trials with available OS results, the sample size required to power for OS was at least fivefold larger than that needed to power for PFS.

Discussion

Our analyses suggest that in the first-line HER2-negative mBC setting, it is a high hurdle to conduct a trial with adequate power to detect an OS improvement. Sample sizes to power for OS are usually extremely large and substantially larger than required to power for PFS.

The generally larger PFS than OS treatment effect in HER2-negative mBC is consistent with a recently reported study across various tumor types.Citation27 Our findings are also consistent with reports in the literature suggesting that demonstrating an OS benefit is becoming increasingly unrealistic in contemporary clinical trials.Citation2 A trial without crossover may answer the question of OS most cleanly. However, if the investigational agent has shown clear activity, the possibility of crossover has to be discussed. An Independent Data Monitoring Committee may feel obliged to stop a trial because of a clear signal, but it will then be impossible to conclude on the secondary endpoint of OS. Furthermore, a second trial of the same agent cannot be conducted after proven benefit because it is difficult to consent patients to be randomized between an experimental agent and a control arm known to be inferior. At times of rapid innovation, endpoints allowing prompt application of therapy optimization to standard clinical care are required. Therefore, it is important to determine whether progression-based endpoints are suitable for demonstrating utility. Available endpoints include PFS, TTP, and time to treatment failure. These allow earlier provision of study results and can be more sensitive indicators of treatment benefit because they are not affected by further treatment lines or crossover.Citation28,Citation29 Another benefit is comparability, as PFS is currently the most commonly used primary endpoint in Phase III trials. However, there is no clear evidence that PFS is a surrogate for OS.

In a recent analysis of PFS and OS in 58 randomized Phase II/III trials evaluating first-line systemic therapy for HER2-negative hormone receptor-positive mBC, several factors besides first-line therapy were reported to influence OS.Citation30 These included prior endocrine therapy, prior (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy, types and lines of postprogression therapy, as well as disease characteristics associated with prognosis. Geographic region also influenced OS, presumably because of differences in healthcare patterns, management, and access in different countries.

In our analysis, the trial in which the actual sample size and the retrospectively calculated sample size for OS were most similar was IMELDA, a maintenance trial evaluating the addition of capecitabine to maintenance bevacizumab after bevacizumab/taxane induction therapy as a new treatment approach.Citation24 In these patients already demonstrating chemosensitivity to induction therapy, switching to capecitabine before progression potentially anticipates development of resistance. In IMELDA, a significant OS benefit was demonstrated with a relatively small sample size but the retrospectively calculated sample size suggested that a larger sample size was needed. This is explained by differences in the methodology used for sample size calculation compared with the trial analysis method. Importantly, sample size calculation is only an estimation. Conversely, trial outcome is not proof and there is 5% error for demonstrating a significant benefit.

There appeared to be a gradual increase in median OS in the investigational arm over time (). Such cross-trial comparisons have obvious limitations, particularly when including maintenance vs treatment strategies. Nevertheless, median OS with experimental therapy remained <2 years in all trials evaluating chemotherapy alone, crossing the 2-year threshold only with the introduction of targeted therapy (bevacizumab). This presumably reflects not only treatment effect but also earlier diagnosis, better disease management, and an increase in the number of subsequent therapy options available. Indeed, similar increases in median OS can be seen in the control arm.

Given these challenges, how should we test effectiveness most appropriately in the first-line HER2-negative mBC setting? While Health Technology Assessment bodies worldwide accept PFS as a meaningful endpoint for clinical trials, progression-based outcomes are not recognized in Germany by the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Services and the Joint Federal Committee (G-BA). These organizations focus on QoL, safety, OS, and morbidity, whereas PFS alone is not considered a meaningful endpoint, nor (in contrast with the clinical view) as an aspect of morbidity. The rationale for the G-BA’s stance is that superior progression-based outcomes evaluated by imaging are not considered to represent relevant benefits for patients. Patient relevance is accepted only if progression is recorded, for example, through symptoms perceptible to the patient. However, guidelines recommend assessing tumor burden every 8 weeks to allow prompt detection of metastatic progression, discontinuation of ineffective treatment with associated side effects, and prevention of tumor-associated symptoms that could be avoided by a change of treatment or strategy.Citation31

Irrespective of surrogacy for OS, many believe that PFS is an important and relevant outcome for patients, associated with improved overall QoL, physical functioning, and emotional well-being.Citation32 Extending PFS was ranked as more important than tumor shrinkage, limiting side effects, or treatment frequency in a questionnaire-based survey. Self-rated QoL was the highest after respondents had been told that their disease was responding to treatment. Therefore, progression-based parameters should generally be accepted as patient-relevant endpoints. Furthermore, changing therapy at progression affects patients’ lives. A new therapy may be associated with new side effects and/or a new treatment schedule and mode of administration. The consequences of disease progression are depressive reactions, grief, and despair. The possibility of tumor control is the most important reason for patients agreeing to systemic therapy.Citation33 Fear of disease progression is the most commonly reported psychological burden in patients.Citation34

We acknowledge that PFS is not a perfect endpoint, potentially being influenced by assessment intervals, choice of target lesions, and measurement technology. Some of these challenges are overcome by Independent Central Review, which is important for accepting PFS as an endpoint. Regarding the limitations of OS, several elegant biostatistical methods have been developed to account for crossover, such as inverse probability of censoring weighting (IPCW) and the rank-preserving structural failure time (RPSFT) model.Citation35,Citation36 However, these approaches are not flawless: IPCW assumes that there are no unknown or unmeasured confounding factors that could influence crossover and OS, whereas RPSFT assumes that the effect of treatment is constant across time and/or treatment lines. No single validated standard for statistical correction of crossover has been established in settings with long postprogression survival.

With the increasing use of maintenance therapies, eg, in ovarian cancer, alternatives to PFS and OS have emerged, including intermediate endpoints such as time to second progression or time to first or second subsequent therapy.Citation37 These endpoints merit consideration in future trial designs in HER2-negative mBC. For trials evaluating endocrine therapies, time to first chemotherapy can also be a valuable endpoint, with clear patient relevance. Alternative endpoints used in other tumor types include quality-adjusted time without symptoms or toxicity and quality-adjusted PFS. However, it is essential that any endpoint is clearly defined and that the precise definition is used consistently across trials measuring the effect of treatment.Citation38 Changes in molecular markers may also be of interest as surrogate endpoints.

In an attempt to quantify the medical benefits of new drugs, composite scales including pharmacoeconomic parameters have been introduced, such as the European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS)Citation39 and the American Society of Clinical Oncology Value Framework.Citation40 A recent survey indicated that many trials demonstrating statistically significant improvements in efficacy did not meet the ESMO-MCBS clinical benefit threshold,Citation41 particularly trials in the palliative setting.

The challenge of large sample sizes required to show OS improvement in clinical trials has been accompanied by increased interest in real-world data (RWD). In some cases, RWD evaluation has suggested improved OS from a treatment despite the lack of OS benefit in prospective randomized clinical trials.Citation42 The main advantages of RWD are the very large sample sizes available for analysis and inclusion of broader, more heterogeneous patient populations with common comorbidities than is possible in a clinical trial, reflecting populations presenting in routine oncology practice. However, there are many limitations and even with sophisticated statistical methodology, RWD are exposed to important potential biases.Citation43 Therefore, RWD can be viewed only as complementary to randomized clinical trials, not as an alternative.

A limitation of our analysis is the focus on chemotherapy and antiangiogenic agents. Numerous ongoing trials in the first-line HER2-negative mBC setting are evaluating cancer immunotherapy agents, which have a different mode of action and thus may exhibit different effects on PFS and OS. Furthermore, many of these trials focus on triple-negative mBC, a slightly more homogeneous population with shorter OS expectancy, shorter postprogression survival, and fewer treatment options after progression. All of these factors may affect the ability to demonstrate a significant OS effect, and, therefore, the patterns observed in our analysis may not predict future trials of cancer immunotherapy. Interestingly, several ongoing Phase III trials of immunotherapy in triple-negative mBC evaluate OS as the (co)primary endpoint. Another potential criticism is that the proportion of patients completing treatment is not taken into account. This information is missing in some of the publications, particularly in the older trials, but may have an impact on outcomes.

Conclusion

Although there are many reasons why OS is an attractive endpoint in trials of first-line therapy for HER2-negative mBC, it has limitations. Designing trials to test potential new treatments for HER2-negative mBC is challenging and requires a balance of regulatory acceptability, feasibility, and realistic medical assumptions to calculate sample sizes, which can be particularly difficult in heterogeneous study populations with long postprogression survival and heterogeneous subsequent therapies. The magnitude of OS benefit likely to be considered as clinically (as well as statistically) significant depends on disease biology and risk. For example, in patients with triple-negative mBC, a 3-month improvement in median OS is undoubtedly meaningful, whereas in hormone receptor-positive mBC, a larger (6-month) improvement may be required to provide convincing meaningful benefit. In the current environment amid soaring costs and fierce competition,Citation44 it is probably unrealistic to aim for trials demonstrating statistically significant OS improvement in this setting, except for trials in very specific poor prognosis populations. Ultimately, identification of robust alternative endpoints reflecting relevant patient benefits remains critical.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Jennifer Kelly, MA (Medi-Kelsey Ltd, Ashbourne, UK) and funded by Roche Pharma AG. This work was funded by Roche Pharma AG, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany. A poster reporting a preliminary analysis of this topic was presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) congress in Madrid, Spain; 8–12 September, 2017. The abstract from the poster was published in the congress proceedings.Citation45

Data availability

All data used for the analyses reported in this paper are taken from the cited publications.

Supplementary material

Table S1 Search strategy for identification of eligible trials

Disclosure

SKü and CJ have participated on advisory boards for Roche Pharma AG. VM has participated on advisory boards for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Genomic Health, Nektar, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Roche, and Teva. SKl is an employee of Roche Pharma AG. MPL has participated on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Genomic Health, and Roche, and has received honoraria for lectures from Lilly, Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, Genomic Health, AstraZeneca, Medac, and Eisai. AS has declared no conflict of interest and the other authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MendesDAlvesCAfonsoNThe benefit of HER2-targeted therapies on overall survival of patients with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer – a systematic reviewBreast Cancer Res20151714026578067

- Di LeoABleibergHBuyseMOverall survival is not a realistic end point for clinical trials of new drugs in advanced solid tumors: a critical assessment based on recently reported phase III trials in colorectal and breast cancerJ Clin Oncol200321102045204712743164

- SargentDJHayesDFAssessing the measure of a new drug: is survival the only thing that matters?J Clin Oncol200826121922192318421044

- BroglioKRBerryDADetecting an overall survival benefit that is derived from progression-free survivalJ Natl Cancer Inst2009101231642164919903805

- AmirESerugaBKwongRTannockIFOcañaAPoor correlation between progression-free and overall survival in modern clinical trials: are composite endpoints the answer?Eur J Cancer201248338538822115991

- KornELFreidlinBAbramsJSOverall survival as the outcome for randomized clinical trials with effective subsequent therapiesJ Clin Oncol201129172439244221555691

- AdunlinGCyrusJWDranitsarisGCorrelation between progression-free survival and overall survival in metastatic breast cancer patients receiving anthracyclines, taxanes, or targeted therapies: a trial-level meta-analysisBreast Cancer Res Treat2015154359160826596731

- LiuLChenFZhaoJYuHCorrelation between overall survival and other endpoints in metastatic breast cancer with second- or third-line chemotherapy: literature-based analysis of 24 randomized trialsBull Cancer2016103433634426874974

- ForsytheAChandiwanaDBarthJThabaneMBaeckJTremblayGProgression-free survival/time to progression as a potential surrogate for overall survival in HR+, HER2– metastatic breast cancerBreast Cancer201810697829765247

- AcklandSPAntonABreitbachGPDose-intensive epirubicin-based chemotherapy is superior to an intensive intravenous cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil regimen in metastatic breast cancer: a randomized multinational studyJ Clin Oncol200119494395311181656

- EjlertsenBMouridsenHTLangkjerSTAndersenJSjöströmJKjaerMPhase III study of intravenous vinorelbine in combination with epirubicin versus epirubicin alone in patients with advanced breast cancer: a Scandinavian Breast Group Trial (SBG9403)J Clin Oncol200422122313232015197192

- JassemJPieńkowskiTPłuzańskaADoxorubicin and paclitaxel versus fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide as first-line therapy for women with metastatic breast cancer: final results of a randomized phase III multicenter trialJ Clin Oncol2001191707171511251000

- von MinckwitzGChernozemskyISirakovaLBendamustine prolongs progression-free survival in metastatic breast cancer (MBC): a phase III prospective, randomized, multicenter trial of bendamustine hydrochloride, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil (BMF) versus cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil (CMF) as first-line treatment of MBCAnticancer Drugs200516887187716096436

- BontenbalMCreemersGJBraunHJPhase II to III study comparing doxorubicin and docetaxel with fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide as first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer: results of a Dutch Community Setting Trial for the Clinical Trial Group of the Comprehensive Cancer CentreJ Clin Oncol200523287081708816192591

- AlbainKSNagSMCalderillo-RuizGGemcitabine plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel monotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer and prior anthracycline treatmentJ Clin Oncol200826243950395718711184

- GrayRBhattacharyaSBowdenCMillerKComisRLIndependent review of E2100: a phase III trial of bevacizumab plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel in women with metastatic breast cancerJ Clin Oncol200927304966497219720913

- CameronDBevacizumab in the first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancerEur J Cancer2008662128

- MillerKWangMGralowJPaclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancerN Engl J Med2007357262666267618160686

- SparanoJAMakhsonANSemiglazovVFPegylated liposomal doxorubicin plus docetaxel significantly improves time to progression without additive cardiotoxicity compared with docetaxel monotherapy in patients with advanced breast cancer previously treated with neoadjuvant-adjuvant anthracycline therapy: results from a randomized phase III studyJ Clin Oncol200927274522452919687336

- RobertNJDiérasVGlaspyJRIBBON-1: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for first-line treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative, locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancerJ Clin Oncol201129101252126021383283

- Roche data on fileAVF3694g clinical study report addendum2009

- MilesDWChanADirixLYPhase III study of bevacizumab plus docetaxel compared with placebo plus docetaxel for the first-line treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancerJ Clin Oncol201028203239324720498403

- LamSWde GrootSMHonkoopAHPaclitaxel and bevacizumab with or without capecitabine as first-line treatment for HER2-negative locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 2 trialEur J Cancer201450183077308825459393

- GligorovJDovalDBinesJMaintenance capecitabine and bevacizumab versus bevacizumab alone after initial first-line bevacizumab and docetaxel for patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (IMELDA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trialLancet Oncol201415121351136025273343

- MilesDCameronDBondarenkoIBevacizumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel as first-line therapy for HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (MERiDiAN): a double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial with prospective biomarker evaluationEur J Cancer20177014615527817944

- MilesDCameronDHiltonMGarciaJO’ShaughnessyJOverall survival in MERiDiAN, a double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial evaluating first-line bevacizumab plus paclitaxel for HER2-negative metastatic breast cancerEur J Cancer20189015315529174181

- TanAPorcherRCrequitPRavaudPDechartresADifferences in treatment effect size between overall survival and progression-free survival in immunotherapy trials: a meta-epidemiologic study of trials with results posted at ClinicalTrials.govJ Clin Oncol201735151686169428375786

- SaadEDKatzAProgression-free survival and time to progression as primary end points in advanced breast cancer: often used, sometimes loosely definedAnn Oncol200920346046419095776

- BurzykowskiTBuyseMPiccart-GebhartMJEvaluation of tumor response, disease control, progression-free survival, and time to progression as potential surrogate end points in metastatic breast cancerJ Clin Oncol200826121987199218421050

- ForsytheAChandiwanaDBarthJIs progression-free survival a more relevant endpoint than overall survival in first-line HR+/HER2-metastatic breast cancer?Cancer Manag Res2018101015102529765249

- ThillMLiedtkeCSolomayerEFMüllerVJanniWSchmidtMAGO recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer: update 2017Breast Care201712318419128785187

- HurvitzSALallaDCrosbyRDMathiasSDUse of the metastatic breast cancer progression (MBC-P) questionnaire to assess the value of progression-free survival for women with metastatic breast cancerBreast Cancer Res Treat2013142360360924218050

- GrunfeldEAMaherEJBrowneSAdvanced breast cancer patients’ perceptions of decision making for palliative chemotherapyJ Clin Oncol20062471090109816505428

- HerschbachPKellerMKnightLPsychological problems of cancer patients: a cancer distress screening with a cancer-specific questionnaireBr J Cancer200491350451115238979

- IshakKJProskorovskyIKorytowskyBSandinRFaivreSValleJMethods for adjusting for bias due to crossover in oncology trialsPharmacoeconomics201432653354624595585

- KorhonenPZuberEBransonMCorrecting overall survival for the impact of crossover via a rank-preserving structural failure time (RPSFT) model in the RECORD-1 trial of everolimus in metastatic renal-cell carcinomaJ Biopharm Stat20122261258127123075021

- KaramALedermannJAKimJWFifth Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference of the Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup: first-line interventionsAnn Oncol20172871171728327917

- Gourgou-BourgadeSCameronDPoortmansPGuidelines for time-to-event end point definitions in breast cancer trials: results of the DATECAN initiative (Definition for the Assessment of Time-to-event Endpoints in CANcer trials)Ann Oncol2015261225052506

- ChernyNIDafniUBogaertsJESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale version 1.1Ann Oncol201728102340236628945867

- SchnipperLEDavidsonNEWollinsDSAmerican Society of Clinical Oncology Statement: a conceptual framework to assess the value of cancer treatment optionsJ Clin Oncol201533232563257726101248

- Del PaggioJCAzariahBSullivanRDo contemporary randomized controlled trials meet ESMO thresholds for meaningful clinical benefit?Ann Oncol201728115716227742650

- DelalogeSPérolDCourtinardCPaclitaxel plus bevacizumab or paclitaxel as first-line treatment for HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer in a multicenter national observational studyAnn Oncol20162791725173227436849

- BuyseMVansteelandtSThe potential and perils of observational studiesAnn Oncol201728118228177426

- PiccartMPondéNCancer drugs, survival and ethics: a critical look from the insideESMO Open201716e00014928848670

- KümmelSJackischCMüllerVSchneeweissAKlawitterSLuxMPCan contemporary trials in HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (mBC) detect overall survival (OS) benefit?Ann Oncol201728Suppl 5v86v87