Abstract

Background

There still remains no well-established treatment strategy for head and neck mucosal melanoma (HNMM). We aim to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of primary surgery with postoperative radiotherapy for this disease.

Patients and methods

A single-arm, Phase II clinical trial was conducted at Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center. Patients with nonmetastatic, histologically proven HNMM were prospectively enrolled. Patients received primary surgery followed by intensity-modulated radiotherapy with an equivalent dose at 2 Gy per fraction of 65–70 Gy to CTV1 (high-risk regions including tumor bed) and 50–55 Gy to CTV2 (low-risk regions). Additional use of adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) depended on consultation from a multidisciplinary team. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT03138642.

Results

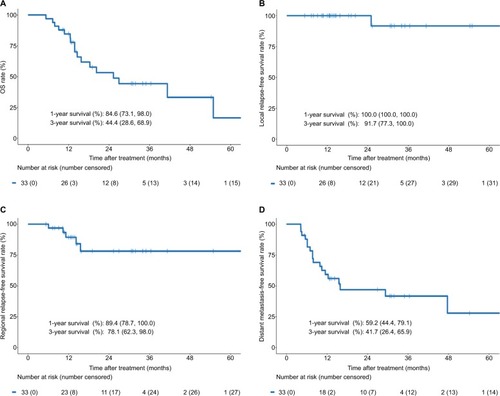

A total of 33 patients were enrolled and analyzed between July 2010 and November 2016. There were 18 (54.5%) patients with T3 disease and 15 (45.5%) patients with T4a disease. The median age at diagnosis was 58 years (range 27–83 years), and 61% of the cohort were males. The overall median follow-up duration was 25.3 months (range 5.3–67.1 months). The 3-year overall survival (OS), local relapse-free survival (LRFS), regional relapse-free survival (RRFS), and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) rates were 44.4, 91.7, 78.1, and 41.7%, respectively. Patients with T4a disease showed significantly inferior OS (P=0.049) and DMFS (P=0.040) than those with T3 disease. Prophylactic neck radiation (PNR) was nearly associated with superior RRFS (P=0.078). However, there was no significant difference in OS, LRFS, RRFS, and DMFS for patients treated with or without AC (P>0.05 for all). Toxicities were generally mild to moderate.

Conclusion

Primary surgery with postoperative radiotherapy yielded excellent local control and acceptable toxicity profile for HNMM. Nevertheless, high rates of distant metastases resulted in limited survival.

Introduction

Melanoma is one of the most malignant cancers, and based on the origin of site, it is subdivided into ocular, cutaneous, and mucosal melanomas. Previous studies have reported that among Caucasians, mucosal melanomas are a rare subdivision (1.3% of all melanomas), whereas in Asians, this subdivision is the second most common (22.6% of all melanomas).Citation1–Citation3 Mucosal melanoma’s overall prognosis is worse than cutaneous and ocular melanomas. Over half of all mucosal melanomas are head and neck mucosal melanomas (HNMM), where nasal, sinonasal, and oral cavity are the most common primary sites.Citation4–Citation6 This malignancy is aggressive, where 5-year survival ranges from 14 to 40%.Citation7–Citation10 Currently, surgery with or without postoperative radiotherapy is the widely accepted standard of care for the treatment of HNMM,Citation10,Citation11 However, the use of adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) has yet to be established as a method for improving treatment outcomes. Although a large multicenter retrospective study among an exclusive Caucasian population reported a 5-year survival rate of 26.7% among patients who received surgery followed by radiotherapy,Citation12 these findings may not be generalizable in Asian populations due to both ethnic- and genetic-related differences between populations. In this study, we prospectively enrolled a predominantly Asian population with HNMM to evaluate both the efficacy and safety of primary surgery with postoperative radiotherapy ± AC in the treatment of HNMM.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a single-arm, Phase II clinical trial at Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center (SYSUCC) in Guangzhou, China. All patients received physical examinations and provided detailed medical history. We also performed comprehensive biochemical laboratory test, blood cell count, fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy, chest and upper abdomen computed tomography (CT) scan, nasopharyngeal and neck magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and single-photon emission CT of bone or positron emission tomography–CT. Detailed inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria are shown in the Supplementary materials. Briefly, participants were considered eligible if they aged ≥18 years and had stage III/IVA mucosal melanoma that was pathologically confirmed diagnosis arising from head and neck.

Procedures

This study was registered with the National Cancer Trial Registry as NCT03138642 (ClinicalTrials.gov). The protocol of this study received approval from SYSUCC’s human ethics committees, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines defined by the International Conference on Harmonization were applied in this study. Detailed information on treatment is presented in the Supplementary materials. Briefly, each patient received primary surgery with or without neck dissection. All specimens were sent for pathological examination. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) was delivered to each patient within 4–6 weeks after primary surgery. The recommendations for additional use of prophylactic neck radiation (PNR) and/or AC were determined by a multidisciplinary team’s consultation.

Follow-up and outcome

Patient’s follow-up visits were at least every 3 months during the first 2 years and every 6 months thereafter. We calculated follow-up from the first day of therapy to the last examination or death. For patients with evidence of local-regional recurrence or distant metastasis, additional examination or imaging modalities were performed to confirm or exclude disease progression at the discretion of the treating physician. Detailed information on follow-up is presented in the Supplementary materials. Based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (Version 4.0), adverse events were recorded at each visit.

Statistical analysis

The endpoints assessed were overall survival (OS), local relapse-free survival (LRFS), regional relapse-free survival (RRFS), and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS). Data for all endpoints were analyzed in all eligible patients who completed the treatment protocol. Data for adverse events, including acute and late complications, were shown using descriptive statistics. Kaplan–Meier method was applied to calculate survival rates with a corresponding two-sided 95% bootstrap CI, and the difference was compared using the log-rank test. Variables with P-values ≤0.05 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariable Cox regression analysis. R Version 3.3.2 was used for all analyses (http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Between July 2010 and November 2016, a total of 34 patients were enrolled in this trial. One patient was excluded due to withdrawal of consent. presents the remaining patients’ characteristics, progression, and treatment. The median age at diagnosis was 58 years (range 27–83 years), and 61% of the total cohort were males. Locations included the nasal cavity without further anatomic detail in 13 cases, maxillary sinus in eight cases, inferior turbinate in five cases, ethmoidal sinus in four cases, and oral cavity in three cases. According to the seventh American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) classification of HNMM, there were 18 (54.5%) patients with T3 disease and 15 (45.5%) patients with T4a disease. No cervical lymph node or remote metastases were on initial assessment, but two (6.1%) patients had a microscopically positive lymph node (N1) after elective neck dissection.

Table 1 Description, progression, and treatment of lesions in 33 patients

Treatment

All patients received an initial regimen of primary surgery. Neck dissection was not performed routinely, where only three (9%) of the 33 patients arising from oral cavity received elective neck dissection. Of the three patients who received elective neck dissection, two patients had a microscopically positive lymph node (N1). However, the above two patients with histologically proven N1 disease developed distant metastasis rapidly within 6 months of starting surgery. The median equivalent dose at 2 Gy per fraction (EQD2) of the tumor site was 68.3 Gy (IQR, 67–70 Gy). A total of 23 (70%) of these patients received hypofractionated conformational radiation therapy and 10 (30%) patients received conformational radiation therapy. The median interval between surgery and radiation therapy was 55 days (IQR, 42–72 days). AC was given to 23 (70%) of the 33 patients, and 10 (43%) of the 23 patients completed at least 4 cycles of chemotherapy. The primary cause for uncompleted chemotherapy was due to patient refusal (39%; 9/23), followed by disease progression during AC (17%; 4/23).

Surveillance

The median follow-up duration was 25.3 months (range 5.3–67.1 months) for the entire cohort. Only one (3%) patient developed local recurrence, and five (15%) patients had regional relapse. The one local relapse was occurred in male aged 67 years with T4aN0 mucosal melanomas arising from the right nasal cavity, right ethmoidal sinus, and nasal septum who received an EQD2 of 70 Gy irradiation after primary surgery within 23 months of starting radiotherapy. The one patient who had regional relapse was treated with elective neck dissection alone, and the other four regional relapse patients did not receive any elective neck dissection and/or PNR. Interestingly, regional control was achieved in all patients treated with PNR (11/11 patients; 100%). For the entire group, 19 (58%; 19/33) patients developed distant metastasis, and 17 patients died (15 patients due to distant metastasis; one patient due to local relapse; and one patient due to noncancer causes). Overall, the 1- and 3-year OS, LRFS, RRFS, and DMFS rates were 84.6 and 44.4%, 100 and 91.7%, 89.4 and 78.1%, and 59.2 and 41.7%, respectively ().

Safety

During radiotherapy, 70% (23/33) of patients suffered radiation-related acute adverse events. The incidence of grade 3 acute adverse events occurred in 18% (6/33) of patients (two patients had dermatitis and mucositis, one patient had anemia and leucopenia, one patient had dermatitis and leucopenia, and two patients had nausea). Radiation-related late complications of grade 3 occurred in 12% (4/33) of patients (two patients had muscle fibrosis, one patient had nasal perforation, and one patient had dermatitis). During chemotherapy, five (22%) of the 23 patients had grade 3 adverse events, and there were no reported grade 4 adverse events. Grade 3 leucopenia was recorded in two (9%) of the 21 patients, with anemia being the most common event following. Nausea (9%), vomiting (4%), and nephrotoxicity (4%) were frequently recorded the most for grade 3 nonhematological adverse events ().

Table 2 Treatment-related adverse events

Univariate and multivariate analyses

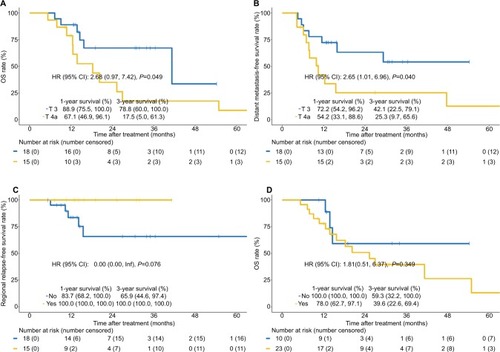

Univariate analysis was performed to identify independent prognostic factors, and the outcomes are shown in . Understandably, T stage was the most important factor in predicting OS and DMFS (P<0.05 for all). The 3-year OS was significantly higher for patients with T3 disease than those with T4a disease (3-year OS, 78.8 vs 17.5%, P=0.049; ). Similarly, T3 disease was significantly associated with better DMFS than T4a disease (3-year DMFS, 42.1 vs 25.3%, P=0.040; ). Interestingly, patients treated with PNR had higher RRFS rate than those without prophylactic neck irradiation, nearly meeting statistical significance (100 vs 65.9%, P=0.076; ). However, there was no significant difference in OS, LRFS, RRFS, and DMFS for patients treated with or without AC (P>0.05 for all) ( and ). Given the limited number of patients in the current study, categorical variables failed to retain significance in multivariate analysis (P>0.05 for all; ).

Table 3 Clinicopathological characteristics and univariate analysis of OS, RRFS, and DMFS in the 33 patients with HNMM

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier analysis of (A) OS and (B) distant metastasis-free survival for patients with stage T3 vs stage T4a; (C) regional relapse-free survival for patients treated with or without prophylactic neck radiation; and (D) overall survival for patients treated with or without adjuvant chemotherapy.

Abbreviation: OS, Abbreviations.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial to analyze the effectiveness and safety of combined primary surgery with postoperative radiotherapy ± AC for HNMM in an Asian population. Our findings indicate that this regimen provides sufficient local control, where distant metastasis remained the major failure pattern for HNMM. Additionally, patients with T3 disease had significantly higher OS and DMFS rates than those with T4a disease. We also found that PNR contributed to the improvement in regional control.

Current evidence suggests that postoperative radiotherapy contributes to improve local control for HNMM.Citation10,Citation13,Citation14 In the present study, postoperative radiotherapy was delivered to each patient and showed to have higher LRFS rates than those reported in previous studies (ranging 23–75%).Citation10,Citation15,Citation16 Our findings could be explained by several reasons. First, developments in radiation technology, such as IMRT, have improved tumor target conformity and reduced local relapse in comparison with two-dimensional conventional radiotherapy (2DCRT).Citation17 Prior studiesCitation10,Citation16,Citation17 were generally conducted in the 2DCRT era, but all patients in this study received IMRT. Therefore, the advance in radiation technology may partly contribute to the sufficient local control in this study. Second, due to tumor rarity, majority of seriesCitation9,Citation10,Citation16,Citation18 extend retrospectively several decades to collect enough patients. In contrast, patients enrolled in this clinical trial were diagnosed within 7 years. We consider that the treatment advances in recent years potentially contributed to higher local control rate. Finally, given the poor survival among HNMM patients,Citation9,Citation10 our findings reveal that high rate of local control was most likely due to some patients died before local relapse could have develop.

Elective therapy of the neck is usually not performed since less than 10% of mucosal melanoma patients present regional lymph nodes.Citation6,Citation10 However, the incidence was much higher in patients with oral mucosal melanoma, which ranged from 25 to 76%.Citation9,Citation19 Consistent with previous studies, our results showed that two of the three (67%) patients had a microscopically positive lymph node after neck dissection. However, the above two patients with histologically proven N1 suffered distant metastasis within 6 months of starting surgery. Therefore, the effect of neck dissection still needs further exploration. Currently, there is controversy over the necessity of PNR in HNMM patients with N0 disease.Citation9,Citation18,Citation20 Our results found that RRFS was 100% for patients treated with PNR, and further analysis revealed that PNR contributed to higher RRFS rate. This infers that routine PNR should be considered in clinical practice even in patients with N0 disease.

HNMM is considered to be a highly malignant tumor, as majority of patients quickly succumb to distant metastases.Citation6,Citation7 For this reason, it is of great importance to add effective systemic therapy for high-risk patients.Citation21 However, prior to the start of the study, there was no systemic therapy regimen demonstrated as effective for HNMM. A recent randomized Phase II trial by Lian et alCitation22 reported that temozolomide with cisplatin contributed to improve survival than that of high-dose IFN-a2b as systemic adjuvant therapy among patients with resected mucosal melanoma. However, we failed to find the effectiveness of adjuvant temozolomide and cisplatin chemotherapy in improving the survival of HNMM. One reason underlying this observation might be due to potential selection bias for AC use. Considering our research design type, we could not deduce whether AC directly improves survival.

In the present study, the 3-year OS rate was 44.4%, which is consistent with previous reports.Citation23–Citation25 Although primary surgery with postoperative radiotherapy with or without AC yielded an excellent local control, we must note that the survival of HNNM was not sufficient enough. Considering that more than 50% of patients suffered distant metastasis within 3 years, the lack of long-term survival benefit from local therapy is likely because of distant metastasis being the major limiting factor. This suggests that improving survival by escalating the intensity of local therapy may not be available, and novel therapeutic paradigms designed to abrogate the risk of distant relapse should be pursued in clinical trials. Further analysis revealed that early-stage HNMM was significantly associated with superior OS and DMFS. Therefore, early diagnosis of HNMM is of great importance to improve survival outcomes.

The primary concern in the present study was serious radiation-related toxicity during conventional irradiation techniques when applied to the region of the head and neck. In the 2DCRT era, the rate of radiation-induced blindness can be up to 40% after 2DCRT for HNMM.Citation26,Citation27 Compared with 2DCRT, IMRT minimizes dose to organs at risk (OARs), while providing a more conformal dose to complex-shaped target volumes, facilitating a lower rate of radiation-induced toxicity.Citation17 This was seen in the present study, where radiation-induced blindness was not observed, and only 12% (4/33) of patients experienced radiation-related late toxicities of grade 3. We hypothesize that the lower rate of radiation-related toxicities in our study is largely due to the technical advantages of IMRT.

We must note that in this trial, some limitations were observed. A major concern was that this trial was from a single center, among an Asian population, and external validation was not performed. However, external validation was not performed mainly due to a lack of data availability from other centers. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other Asian patients. Second, this study was not designed to assess the use of combined primary surgery and postoperative radiotherapy as a mean of selecting patients who might benefit from this approach but to assess the safety and efficiency of patients treated by this approach. Finally, our study was limited by the small sample size and some prognostic factors may not have been fully identified. However, HNMM incidence is low and a large prospective cohort trial would be difficult to develop.

Conclusion

Primary surgery in combination with postoperative radiotherapy ± AC yielded an excellent local control and acceptable toxicity profile. Nevertheless, high rates of distant failure resulted in limited survival. Since risk of distant metastasis is high for this disease, it is important for future clinical trials to use targeted agents or immune modulators to test potentially novel systemic therapies to improve the distant control of HNMM. Further analyses revealed that early stage at initial diagnosis was significantly associated with better survival among HNMM populations. Hence, early diagnosis of HNMM is of great importance to improve survival.

Keypoints

Primary surgery with postoperative radiotherapy was administered to evaluate the efficacy and safety in head and neck mucosal melanoma (HNMM) patients

This regimen provides a sufficient local control (3-year rate, 92%) and has an acceptable toxicity profile in the Asian population.

Distant metastases resulted in limited survival, and early diagnosis of HNMM is of great importance to improve survival.

Data sharing statement

The key raw data have been uploaded onto the Research Data Deposit (RDD) public platform, with the approval RDD number of RDDA2018000801.

Supplementary materials

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Participants were considered eligible if aged ≥18 years and have stages III/IVA mucosal melanoma that was pathologically confirmed diagnosis (in accordance with the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7th edition staging system) arising from head and neck. Additional eligibility criteria included concentrations of hemoglobin ≥90 g/L, platelet count ≥100×109/L, white blood cell count ≥4.0×109/L, absolute neutrophil ≥2.0×109/L, sufficient organ function (less than 2.5 times the normal values of alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase and creatinine clearance rate >60 mL/min), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0 or 1, and agreeing regular follow-up. Participants were excluded if they had distant metastasis, had malignant disease in the past 3 years, or had previously received therapy for their mucosal melanoma. Diagnostic biopsy of the primary site was allowed. Participants were also excluded if they were pregnant or breastfeeding, had serious comorbidities, or had active lupus erythematosus or scleroderma, unstable cardiac disease needing treatment, COPD exacerbation or an acute or fungal infection requiring treatment, or other acute or fungal infection requiring treatment.

Detailed treatment strategy

Each patient underwent surgery with curative intent. Based on tumor location and extension, surgical type and approached were determined. Because of the lack of a proven benefit of elective neck treatment, the decisions were mostly dependent on the location of the primary tumor. Only three patients (3/33, 9%) who had oral mucosal melanoma underwent elective neck dissection. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) was delivered to each patient within 4–6 weeks after primary surgery. Dose modification was not permitted during radiotherapy. Patients are prescribed an EQD2 of 65–70 Gy to CTV1 (high-risk regions including tumor bed) and 50–55 Gy to CTV2 (low-risk regions). Radiation physicians determined prophylactic irradiation to upper neck, and patients were given an EQD2 of 70–77 Gy to CTVnd (clinically negative lymph nodes) and 50–55 Gy to CTVn2 (neck nodal regions). If there is a residual tumor (gross tumor volume [GTV]), an EQD2 of 70–77 Gy is prescribed to GTV.

In most retrospective studies, adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) failed to prolong the overall survival (OS). In the current trial, the recommendations for additional use of AC depended on a multidisciplinary team’s consultation. Additional chemotherapy contained cisplatin and temozolomide (cisplatin [25 mg/m2/day intravenously on the first, second, and third days] and temozolomide [200 mg/m2/day service on the first through fifth day]). Patients received chemotherapy once every fourth week at a 4–6 cycles maximum, or until progression of disease is indicated or patient requests to stop.

Detailed follow-up and outcome

Patient’s follow-up visits were at least every third month during the first 2 years and every sixth month thereafter. We calculated follow-up duration as day 1 of therapy to mortality date or last follow-up. Additionally, fiberoptic endoscopy and biopsy were used to diagnose local relapses. Clinical examination was used to diagnose regional relapse and in uncertain cases, using an magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the neck or fine needle aspiration. Physical examinations, clinical symptoms, and imaging methods comprising bone scan, abdominal sonography, computed tomography (CT), MRI, and/or PET–CT were used to diagnose distant metastases.

Endpoints

The endpoints assessed were OS, local relapse-free survival (LRFS), regional relapse-free survival (RRFS), and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS). We calculated OS as the first date of treatment to death due to any cause. LRFS and RRFS analyses were calculated from the first date of treatment to first local or regional failure, respectively. We calculated DMFS from the date of first treatment to the date of first remote. Treatment-related adverse event was also an endpoint. Based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (Version 4.0), adverse events were recorded at each visit including treatment, follow-up, and end of study.

Table S1 Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for patients with HNMM

Abbreviations

| 2DCRT | = | two-dimensional conventional radiotherapy |

| AC | = | adjuvant chemotherapy |

| AJCC | = | American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| CT | = | computed tomography |

| DMFS | = | distant metastasis-free survival |

| HNMM | = | head and neck mucosal melanomas |

| IMRT | = | intensity-modulated radiotherapy |

| LRFS | = | local relapse-free survival |

| MRI | = | magnetic resonance imaging |

| OARs | = | organs at risk |

| OS | = | overall survival |

| PNR | = | prophylactic neck radiation |

| RRFS | = | regional relapse-free survival |

| SYSUCC | = | Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center |

Acknowledgments

This study was presented in part as an oral abstract at 14th National Congress of Radiation Oncology and China Society for Radiation Oncology & The Sino-American Network for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (CSTRO-SANTRO) new technology and application in radiation oncology (OR-067; Abstract ID, 808544), November 10–12, 2017. This study was funded by the Planned Science and Technology Project of Guangdong Province (No 2016A020215085) and the 308 Clinical Research Funding of Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center (No 308-2015-011). The funders have no involvement in the conduct of the research or preparation of the article.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GutmanMInbarMChaitchikSMalignant melanoma of the mucous membranesEur J Surg Oncol19921843073121521620

- ShooBAKashani-SabetMMelanoma arising in African-, Asian-, Latino- and Native-American populationsSemin Cutan Med Surg20092829610219608060

- ChiZLiSShengXClinical presentation, histology, and prognoses of malignant melanoma in ethnic Chinese: a study of 522 consecutive casesBMC Cancer2011118521349197

- LourençoSVAMSSottoMNPrimary oral mucosal melanoma: a series of 35 new cases from South AmericaAm J Dermatopathol200931432333019461235

- RossMIHendersonMAMucosal melanomaBalchCMHoughtonANSoberAJCutaneous Melanoma5th edSt Louis, MOQuality Medical Publishing2009337350

- MorenoMARobertsDBKupfermanMEMucosal melanoma of the nose and paranasal sinuses, a contemporary experience from the M. D. Anderson Cancer CenterCancer201011692215222320198705

- ManolidisSDonaldPJMalignant mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: review of the literature and report of 14 patientsCancer1997808137313869338460

- JethanamestDVilaPMSikoraAGMorrisLGPredictors of survival in mucosal melanoma of the head and neckAnn Surg Oncol201118102748275621476106

- PatelSGPrasadMLEscrigMPrimary mucosal malignant melanoma of the head and neckHead Neck200224324725711891956

- TemamSMamelleGMarandasPPostoperative radiotherapy for primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neckCancer2005103231331915578718

- TrottiAPetersLJRole of radiotherapy in the primary management of mucosal melanoma of the head and neckSemin Surg Oncol1993932462508516612

- SchmidtMQDavidJYoshidaEJPredictors of survival in head and neck mucosal melanomaOral Oncol201773364228939074

- KrengliMJereczek-FossaBAKaandersJHMasiniLBeldìDOrecchiaRWhat is the role of radiotherapy in the treatment of mucosal melanoma of the head and neck?Crit Rev Oncol Hematol200865212112817822915

- WuAJGomezJZhungJERadiotherapy after surgical resection for head and neck mucosal melanomaAm J Clin Oncol201033328128519823070

- HepptMVRoeschAWeideBPrognostic factors and treatment outcomes in 444 patients with mucosal melanomaEur J Cancer201781364428600969

- SunSHuangXGaoLLong-term treatment outcomes and prognosis of mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: 161 cases from a single institutionOral Oncol20177411512229103739

- SprattDCabanillasRLeeNYThe paranasal sinusesLeeNJLuJJTarget Volume Delineation and Field Setup: A Practical Guide for Conformal and Intensity-Modulated Radiation TherapyBerlinSpringer20134549

- KrengliMMasiniLKaandersJHRadiotherapy in the treatment of mucosal melanoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: analysis of 74 cases. A Rare Cancer Network studyInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys200665375175916647223

- SunCZChenYFJiangYEHuZDYangAKSongMTreatment and prognosis of oral mucosal melanomaOral Oncol201248764765222349277

- NandapalanVRolandNJHelliwellTRWilliamsEMHamiltonJWJonesASMucosal melanoma of the head and neckClin Otolaryngol Allied Sci19982321071169597279

- NarasimhanKKucukOLinHSSinonasal mucosal melanoma: a 13-year experience at a single institutionSkull Base200919425526220046593

- LianBSiLCuiCPhase II randomized trial comparing high-dose IFN-α2b with temozolomide plus cisplatin as systemic adjuvant therapy for resected mucosal melanomaClin Cancer Res201319164488449823833309

- JangardMHanssonJRagnarsson-OldingBPrimary sinonasal malignant melanoma: a nationwide study of the Swedish population, 1960-2000Rhinology2013511223023441308

- ChengYFLaiCCHoCYShuCHLinCZToward a better understanding of sinonasal mucosal melanoma: clinical review of 23 casesJ Chin Med Assoc2007701242917276929

- MeletiMLeemansCRde BreeRVescoviPSesennaEvan der WaalIHead and neck mucosal melanoma: experience with 42 patients, with emphasis on the role of postoperative radiotherapyHead Neck200830121543155118704960

- KatzTSMendenhallWMMorrisCGAmdurRJHinermanRWVillaretDBMalignant tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinusesHead Neck200224982182912211046

- ShumanAGLightEOlsenSHMucosal melanoma of the head and neck: predictors of prognosisArch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg2011137433133721502471